897491 ~ ARTHUR BARRIE DOBBS

An unclaimed New Zealand Defence Force Service Medal (NZ DSM) for a soldier who had been conscripted for training under the CMT scheme in the 1950s has been united with a retired Fairlie farmer.

Barrie DOBBS has lived his whole in South Canterbury. Born in Waimate, Barrie as he is known, is the son of a Waimate farmer Henry Ludwig DOBBS and Mavis Elizabeth DICKSON. Henry Dobbs, his brother William H. (Jnr) and their sons when old enough, were variously involved for a number of years in the construction of the irrigation schemes around Waimate and at the Levels near Ashburton.

Barrie was the first born son followed by William Henry (Jnr), Brian John, Elizabeth Mary and Bruce John Dobbs. While the remainder of his siblings stayed and initially with their father in and around Waimate, Barrie left school at 16 to take up a joinery apprenticeship in Fairlie. From joinery Barrie progressed into carpentry and building until he was balloted for Compulsory Military Training (CMT) in 1953.

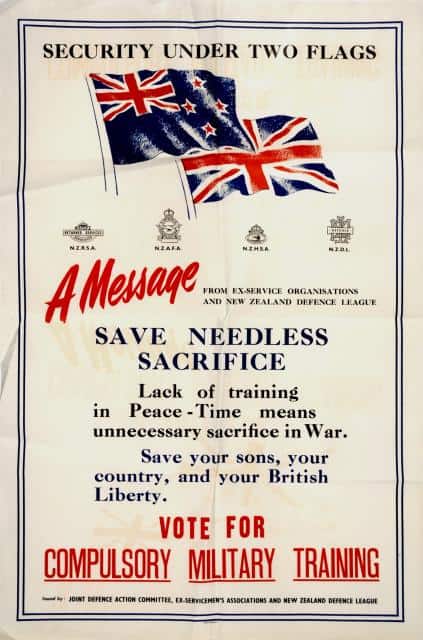

CMT introduced

Under the Military Training Act 1949 which came into effect in 1950, all males became liable for military service upon reaching 18 years of age. They were required to register with the Department of Labour, and apart from those exempted for medical, compassionate or conscientious objection reasons, had to undergo 14 weeks of intensive full-time training, three years of part-time service and six years in the Reserve; all had the option of serving with the Royal New Zealand Navy, the New Zealand Army, or the Royal New Zealand Air Force. A total of 63,661 men were trained before the Military Training Act was replaced by the Labour Government’s National Service Registration Act 1958 towards the end of 1958 which heralded the introduction of National Service in 1961. A combined total in excess of 71,000 completed CMT Scheme in all three Services between 1950 and 1958; approximately 23,319 men were trained in National Service 1962 -1972.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

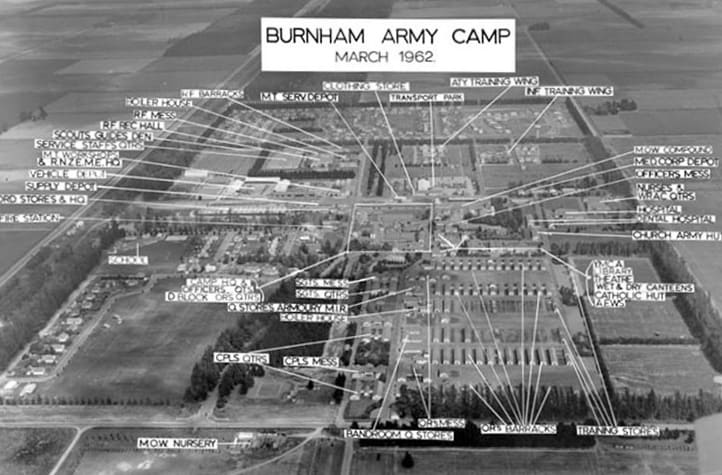

Burnham Military Camp

897491 Private Arthur Barrie DOBBS was balloted for the 10th CMT Intake to commence in 02 July 1953 at Burnham Military Camp, 30 km south of Christchurch. Mid winter at Burnham is not the best time of year to be introduced to the rigours of military training, and true to form the weather did not disappoint with just a touch of the howling, cold easterly winds thrown in for good measure – toughen up soldier !

14 weeks of drill, dress, kit and hut maintenance, inspections, haircuts, plenty of food, fieldcraft, PT, rifle shooting, route marching, confidence course, map reading, and living in the field at the satellite camp at Tekapo … and of course no Intake would be complete without its usual compliment of disorganised soldiers or those with two left feet ‘chasing the bugle’. This is a euphemism for those CMTs who committed minor offences worthy of requiring a ‘modification’ of attitude and/or application to the training and the military way of doing things. For instance, a dirty rifle, having a button undone, forgetting to shave (or not shaving close enough), brass no sparkling on the web belt and hat badge, blanco (green gunk) not applied evenly to anklets and web belt, ‘tram tracks’ ironed in shirt sleeves or trousers, spit-polished boots not up to the ‘required’ standard (whoever knew what that was?), a poorly made bed roll not squared, moving your eyes or fainting on parade, where just some of the reasons corrective training would be required.

These lucky soldiers would be the recipients of special, personal supervision who would experience state of the art character building exercises that would ‘bring them up to speed in double quick time. Simple little exercises such as doubling (running) around the parade ground with their rifle held above their head whilst responding to orders barked at them by a ‘screaming skull’ (Corporal or Sergeant Instructors) was a favourite that gained fairly immediate compliance after the first circuit. ‘Change Parades’ was another favourite (usually after hours) which required soldiers to change into various specified uniforms, or outfits of mixed dress that usually bore no resemblance to approved army dress styles, fiendishly devised by the Orderly NCO. These parades were invariably done on the run with (minus) 3 minutes in which to complete the change and return to the Orderly NCO’s office – success was hopeless. The seemingly endless drill sessions with and without rifles on the Parade Ground (hallowed soil referred to as ‘God’s Zone’) which if steped upon (even after hours or at weekends) by some hapless CMT, would likely incur the wrath of the RSM with eyes in the back of his head, and behaviour modification regimes that once experienced one never wished to repeat. Marching in slow time, double time or marking time (rain, hail, snow, or shine) was a variation on the quick march theme but far more onerous after 30 minutes or more – the list of amusements dished out to “idle” CMTs in order gain their attention and/or compliance was limited only to the imagination of the NCO in charge. Add to this the extremes of weather that Burnham could produce in a day and you have some idea of the joys of a CMT soldier’s life in the Army.

Fourteen and a half weeks later, a shattered but somewhat thinner and fitter Pte. Dobbs headed back to the relative peace and tranquillity of Fairlie and his rip saws and wood-planes. Barrie complied with the remainder of his CMT obligation that required three years of part-time training at weekends and the annual camps held at Tekapo and in its vast training area boundaries. The final requisite of obligation under the CMT scheme was to remain on the Reserve for six years.

From this period in Barrie’s life the only plus as far as he was concerned was that it had resulted in him meeting his future wife at Tekapo, Margaret (Peg) Mary BROSNAN. Once free of his military obligations Barrie and Margaret started going out together and eventually were married in 1959. Shortly afterwards Barrie decided to hang up his apron and wood-plane in favour of a return to the farming life. He leased a property at Brinklands in 1961 (5km SSE of Fairlie) and on Queen’s Birthday weekend 1963, bought the farm where he and Margaret raised their family of five sons – Kevin Henry, Anthony Barrie, Peter Francis, Stephen John and Murray Patrick Dobbs.

After 21 years of farming Barrie and Margaret decided upon retirement, leaving one of their sons to take over the farm in 1984 while they took up residence in the ‘big smoke’, the teaming metropolis that is Fairlie.

Where is your medal Grandad?

It was Barrie’s grandson Cameron, a student at McGlashen High School in Dunedin, who alerted Barrie to the possibility of a medal for his army service. I first met Cameron when he applied for a Victory Medal we had advertised on our Medals~FOUND page that had belonged to his great uncle George Dines (see 23/38 GEORGE WILLIAM DINES). He subsequently contacted me asking if his grandfather Barrie was entitled to any medals as he had been at Burnham Camp in the 1950s. I soon discovered Barrie had been conscripted under the CMT Scheme and therefore was probably entitled to receive the NZ Defence Service Medal with clasp “CMT”. After checking Barrie’s CMT service met all the necessary criteria, I sent Cameron an application for him to complete on his grandfather’s behalf as Anzac Day was only about a month away and given his age, I was confident the helpful staff at NZDF Personnel Archives & Medals (PAM) would action it quickly– and they did.

The Medal

Following a NZ Defence Joint Working Group that was convened to review NZDF medallic recognition including qualifying criteria and the assessment of historical service claims, one of the outcomes was an acknowledgement of Compulsory Military Training (later National Service). Conscripted service that entailed on-going obligations to the State was reconsidered and decided it did warrant medallic recognition. The result was a medal instituted in 2011 to recognise attested military service for personnel in all arms of the New Zealand Defence Force .

New Zealand sailors, soldiers and airmen who attested and served for three or more years since the end of World War Two, and who completed their compulsory military training obligations under the Military Training Act 1949 and its Amendments, are eligible for the Medal with a Clasp inscribed either: C.M.T., Territorial, National Service, Regular denoting the type of service rendered. More than one type of service clasp may be worn on the ribbon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Barrie had not been aware of the NZ DSM and was doubtful at what Cameron had told him. Being somewhat embarrassed by the thought of a medal for his CMT service Barrie had put the application aside as he was reluctant to apply. I enquired with Cameron after a month or so and asked how had he got on with his granddad’s application – Cameron had completed the application and left it with his grandfather Barrie simply to sign and post, but nothing had yet been done. I called Barrie’s wife Peg and asked her if Barrie had sent his application away as Anzac Day was getting close and Cameron was hoping to accompany his granddad to the Cenotaph on the day. Peg came back to me – Barrie was not sure about it still, and no, he had not yet posted it. I re-assured Barrie via Peg he was fully qualified and therefore entitled, that thousands of CMT soldiers had claimed their medals and he should not feel the slightest bit self-conscious about claiming what was a government approved entitlement. With a bit of additional prompting from Peg, Barrie signed the form and sent it away.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks to Karley and the crew at PAM Trentham, Barrie’s medal arrived at his home in Fairlie on the 23rd of April, just in the nick of time for Anzac Day. The 25th was a particularly cold, miserable day in Fairlie this year so Barrie, now in his 80s, decided that wearing his new medal at home with his poppy would have to suffice this year in paying his respects to those in his family no long alive, who had served and died.

Grandfather Barrie and grandson Cameron Dobbs are planning to parade together at the Fairlie Cenotaph with their respective medals on Anzac Day 2019 – temperatures and weather permitting.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My thanks to Cameron for gathering the background for this story and for getting Granddad’s NZDSM (CMT) organised for him – better late than never Barrie.

The reunited medal tally is now 213.

The following is a soldier’s personal perspective on his CMT training at Burnham in 1954:

Compulsory Military Training: a time when New Zealand’s ardent young men were required to do some soldiering – telling it like it was.

Southlander Leo Ward reflects on the experience:

We assembled, as ordered, at Invercargill railway station. Some of us were excited about the trip; some didn’t want to get on the train as girlfriends were clinging to them like octopuses.

One or two had wives. Mums and dads were in a huddle with their beloved sons. Others were so pissed they didn’t care where they went.

Medical checks had deemed us fit enough to be part of Her Majesty’s NZ army – the part to be known as the Ninth Intake 1953. We would be transported by train to Burnham Camp, to be trained for 12 to 14 weeks.

Most of us had never been past Dunedin, but we knew the army camp was near Christchurch.

We had various station stops to pick up more recruits so the scene was repeated at each stop. By this time those with a belly full of grog would be yelling to the girls “let him go, let him go – my brother will look after you”.

We arrived at Burnham station early in the morning. It was cold from a hard frost. Army guys were trying to get some order, but we looked and acted like refugees.

All that was about to change once they got us through the main camp entrance and herd us on to what became known as the “bull ring.” Suddenly, many officers were yelling at us from all directions.

After breakfast and a welcome cup of tea (no coffee then) we were allocated to our quarters, which were 24-man rooms, then to pick up a bed roll and make our bed.

That bed was to become our biggest curse until the day we left.

Every day there was a hut inspection and that bed had to be perfect with your polished boots at the end of it.

If it didn’t pass inspection you had to report for various duties around the camp such as kitchen cleaning and toilets, scrubbing, sweeping, etc.

The toilets were an embarrassment and had everyone feeling a bit shy. They were a long row and had no doors. We looked like those hens that were kept in cages. Reluctant as we were, nature prevailed in the end.

Before starting basic training we were issued with a uniform and a number. We would have liked a word with whoever it was who invented a uniform with brass buttons, brass buckle, brass badge, which had to be polished every day.

We were now under the care of Lance Corporals; guys who were in earlier intakes and who wanted a career in the regular army.

They were little bastards. It was their job to teach us how to march, and everything that went with it.

They hounded us from daylight until dark.

We also learned we were to march through the streets of Christchurch, because it was the Queen’s Coronation so we had to look good.

And we were top class when the big day arrived.

We were issued with a .303 rifle, it also had a number that had to be remembered and pass endless inspections of the barrel. We learned how to slope arms, order arms, present arms, how to fire it, and how to clean it and how to march with it.

After weeks of basic training we moved to core training. This is where we excelled; we were infantry soldiers, so they told us.

They taught us how to dig a trench, then how to fill it in, how to fire a sten gun, a bren gun, throw hand-grenades, bayonet charges, obstacle courses cross rivers, climb walls. We were super fit and well trained by excellent officers.

We had plain food, regular sleep, no alcohol, and we also learned to stop drinking tea.

At our age we had occasional below-the-belt stirrings that we attended to by playing pocket billiards, scratching and fidgeting.

Word went round camp that there was something strange in the tea.

Guys told me later it took some time to get it out of your system. I think I still have some in mine – I wonder if I can claim ACC? Burnham was excellent training for us, it turned us into men, it taught us hygiene, discipline, punctuality, obedience, comradeship.

When we caught the train home, you would not have thought we were the same bunch that had arrived three months ago. Those memories stay with you forever.

We still had weekend camps to attend, two or three times a year.

We slept on hard bales of wool under the old grandstand at the show-grounds. No wonder our backs played up in later years. Others slept in the horse boxes.

Rifle shooting at the Otatara range filled in most of the weekend.

Then came the annual camp at Tekapo, end of January 1954. After arriving by train at Fairlie we were transported by army trucks to our base camp. We were in the hottest part of New Zealand, sleeping six to eight to a tent.

It was the year the polio epidemic was sweeping through New Zealand, so with your mates coughing, farting and sneezing every night, a tent wasn’t the best involvement to be in.

We had a free period at the hottest part of the day from 1pm to 3pm.

Most of the guys had just finished their Christmas holidays and had started work then had to go to camp.

Quite a few of us were farmers’ sons, also sawmillers, coal miners, fishermen, freezing workers and a good number attached to apprentices in the building industry, so three weeks away at that time of year did not go down well with employers.

Our lips cracked and were sunburnt, Otol was the best sunscreen, if you could get it. Orange juice and water were our main liquid intake and we drank gallons of that.

There’s always one or two people who stand out in a camp. I went to school with this chap; a real dare devil, tough as old boots and he could stand any sort of punishment.

Rusty was in trouble the first day he put his army uniform on. He just wasn’t interested in this life and by the time this camp was finished the army wasn’t interested in him.

Rusty never learned to march; that’s why we put him in the front row. He always had an arm or leg out of sequence. Officers got quite wild with him and yelled at him to get into step.

One day Rusty yelled back “I can’t”.

The officer yelled back: “Jump in the bloody air and you might land on the right foot.” Rusty was good at two things, he could ride a horse and a motorbike.

There were no horses at Tekapo but Rusty stumbled across an old Indian bike just on dark. He got this thing going and did a lap and a half of the camp then decided the open road was his next calling. But he only got as far as the main gate, where he spluttered to a grinding halt.

He had run out of petrol, and into the arms of the guards.

Next afternoon Rusty was in the middle of the “bull ring”. He’d been put on a charge for his misdemeanour.

It was very hot and he was in full battle gear. The officer was giving him absolute hell.

Rusty could hardly move. Then came the order to change into PT (physical training) gear. He had to run up to his tent get changed and back as fast as he could with the officer yelling at him all the way. PT gear was singlet, shorts plus gym shoes and grey coat.

Rusty made it back and was standing to attention looking straight ahead, wondering what was going to happen next. He was ordered to remove his coat.

Then came the next instruction: “Get the f*** out of here. I don’t want to see you again.” It turned out Rusty had no clothes on, other than the coat and his gym shoes.

No one was put on charge after that.

One more incident at that camp…

It concerns a guy who came through the ranks (one of the boys) who was promoted to an officer. It’s strange how a uniform or promotion gives some people such a sense of self-importance.

This chap came from the Officers’ Mess and he’d had a bit to drink. We were playing cards, and drinking orange juice. He started saying some smart things to us then one of our chaps, Graham, answered him back, saying it wasn’t very good him coming here half pissed and ordering us around.

The officer ordered him out of the tent, made him stand to attention and gave him a real dressing down.

I could see the muscles on Graham’s arms and face tightening and I’m thinking I hope you don’t do what I think you want to do.

Graham said to me after “when I get out of this camp and out of this uniform, I’ll fix that bastard”. That officer had no friends after that incident.

I wonder how it finished? This was a wonderful group of Southlanders; we supported and enjoyed each other’s company.”

Article courtesy of The Southland Times, 17 July 2010