Guidance for New Zealanders …. Honouring the Fallen

National Days of Remembrance ~ New Zealand & Australia

ANZAC DAY – 25th April

New Zealanders soon demanded some form of remembrance on the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings. This became both a means of rallying support for the war effort and a public expression of grief – for no bodies were brought home. On 5 April 1916 a half-day holiday for 25 April was gazetted for government offices, flags were to be flown, and patriotic meetings and church services would be held.

The New Zealand Returned Soldiers’ (later Services) Association, in co-operation with local authorities, took a key role in the ceremony, organising processions of servicemen, church services and public meetings. The ceremony on 25 April was gradually standardised during and after the war. It became more explicitly a remembrance of the war dead and less a patriotic event once the war was over.

The Anzac Day ceremony is rich in tradition and ritual. It is essentially, a military funeral with all the solemnity and symbolism such an event entails: uniformed service personnel standing motionless around a memorial, with heads bowed and weapons reversed; a bier of wreaths laid by the mourners; the chaplain reading the words from the military burial service; the firing of three volleys; and the playing of the Last Post, followed by a prayer, hymn, and benediction.

ANZAC or Anzac? This is a frequently debated issue however the protocol is quite clear:

- ANZAC – Upper case is only used when referencing the troop formation that is either the Australian & New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) or part thereof e. g. “the landing of the ANZAC Divisions”, “the ANZAC landing”, “the 2nd ANZAC Battalion” etc. During WW1 the ANZAC Mounted Division operated in the Sinai and Palestine; the NZ and Australia Divisions were combined and re-named I ANZAC Corps and II ANZAC Corps. In WW2 the Australian Corps HQ was combined with the 2nd NZ Division and officially re-named the ANZAC Corps. During the Vietnam War, two companies of 1st Battalion RNZIR were integrated with 4 Royal Australian Regiment and officially became the 4 RAR/NZ (ANZAC) Battalion.

- Anzac – Lower case is used at all other times such as when referring to names, places, things or events e. g. Anzac Day, Anzac Cove, Anzac biscuits, Anzac Avenue, Anzac Carnival, the Anzac fountain, the beach at Anzac, etc.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

ARMISTICE DAY – 11th November

At the “eleventh hour, on the eleventh day, of the eleventh month” (11.11.11) in 1918, the Armistice was signed thus formally ending the First World War. Armistice Day as it was known, was observed in New Zealand between the World Wars, although it was always secondary to Anzac Day. As in other countries, New Zealand’s ‘Armistice Day’ was changed to ‘Remembrance Day’ after World War II but this was not a success. By the mid-1950s the day was virtually ignored, even by churches and veterans’ organisations.

Remembrance Sunday

In addition to observing Armistice Day, Remembrance Sunday has become a universal time of remembrance when those who have died serving their country are specifically commemorated in church services throughout New Zealand.

In New Zealand, Remembrance Sunday is observed on the second Sunday in November. A national commemorative service, hosted by the New Zealand Defence Force, is held in the Cathedral of St Paul in Wellington. The service includes a parade of flags from Navy, Army and Air Force, the RNZRSA and Merchant Navy. The fourth stanza of Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’ is recited. It is traditional to wear the Flanders Poppy or a small red Remembrance Rose, on this occasion.

Two Minutes Silence

The ‘period of silence’ was first proposed by Melbourne journalist, Edward George Honey, in a letter published in the London Evening News on 8 May 1919. His letter came to the notice of King George V, and on 7 November 1919 the King issued a proclamation that called for a two minute silence:

“All locomotion should cease, so that, in perfect stillness, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated in reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.”

Remembrance ceremonies are timed to coincide with the 11.11.11 timings. At this hour all flags are lowered to half mast or dipped if hand-held, as a bugle sounds the ‘Last Post’. A two minute period of silence is then observed at war memorials and at other public spaces across New Zealand, symbolising the official end of the First World War by providing a specific point in time to remember those military personnel who served and died. A second bugle call then sounds the ‘Rouse’ (incorrectly called ‘Reveille’) at which time flags are re-raised – those on flagpoles are raised to the mast-head and those on hand-held staffs that have been dipped during the ‘Last Post’ are bought back to an upright position.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The POPPY

RED Poppy – for Remembrance

The connection between the red Flanders Poppy (also known as the Remembrance Poppy) and the Fallen – service personnel killed or died in war (and those whom have died as a result of military service), has its origins in the Napoleonic Wars of the early nineteenth century. Red (Flanders) poppies were the first flowers to bloom over the graves of soldiers in bombed and pulverized landscapes of northern France and Belgium during the First World War. They served as a vivid reminder of the sacrifice, and commemorate the blood that has been shed during war.

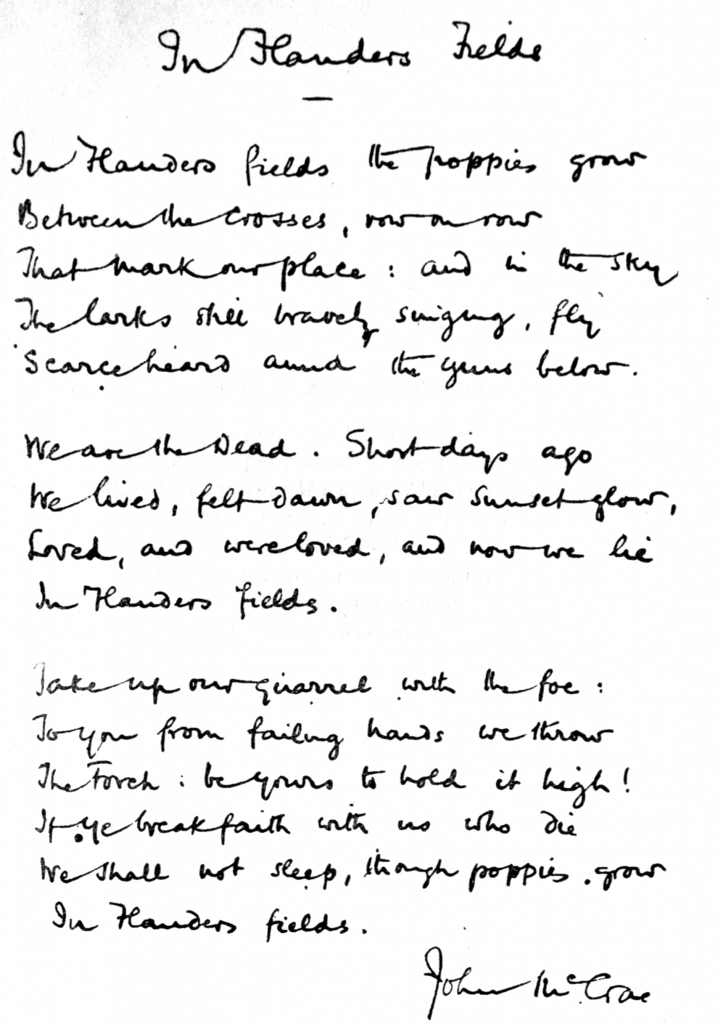

It was in the same region (known as the ‘Western Front’) a century later that red poppies were once more associated with those who died in war when Canadian medical officer Lt Col John McCrae penned the first two famous and moving lines of his poem:

‘ In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row …’

Lt-Col John McCrae MD, CFA

The inspiration for the poem had been the burial of a fellow officer during the Second Battle of Ypres in early May 1915. McCrae’s verses, which had been scribbled in pencil on a page torn from his dispatch book, were sent anonymously by a fellow officer to the English magazine, Punch, which published them under the title In Flanders Fields on 8 December 1915. Subsequently, the poem was published around the world to much acclaim and is one of the most memorable and moving poems of the Great War.

The Challenge

Three years later, McCrae himself died of pneumonia at Wimereux near Boulogne, France, on 28 January 1918. On his deathbed, McCrae reportedly lay down the challenge:

“Tell them this, if ye break faith with us who die, we shall not sleep.”

The Response

Among the many people moved by McCrae’s poem a YMCA canteen worker in New York, Miss Moina Michael (1869-1944), who, two days before the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, wrote a reply entitled ‘We Shall Keep the Faith’ –

We Shall Keep the Faith

Oh! You who sleep in Flanders Fields,

Sleep sweet-to rise anew!

We caught the torch you threw

And holding high, we keep the Faith

With all who died.

We cherish, too, the poppy red

That grows on fields where valour led;

It seems to signal to the skies

That blood of heroes never dies,

But lends a lustre to the red

Of the flower that blooms above the dead

In Flanders Fields.

And now the Torch and Poppy red

We wear in honour of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

We’ll teach the lesson that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.

Miss Michael also originated the idea of the red poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

Origins of the Memorial Poppy

The idea for the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy, Moina Michael recalled in her 1941 book, ‘The Miracle Flower’, came to her while working at the YMCA Overseas War Secretaries’ Headquarters on a Saturday morning, 9 November 1918. The Twenty-Fifth Conference of the Overseas YMCA War Secretaries was in progress. During a lull in proceedings Moina glanced through a copy of the November Ladies Home Journal and came across McCrae’s poem re-titled “We Shall Not Sleep”. The last few lines transfixed her:

To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.Moina Michael hereafter made a personal pledge to ‘keep the faith’ and vowed always to wear a red poppy of Flanders Fields as a symbol of Remembrance. Compelled to make a note of this pledge she hastily scribbled her response, entitled “We Shall Keep the Faith”, on the back of a used envelope.

When the Conference delegates gave Moina a gift of ten dollars in appreciation of her assistance, she went to a New York department store and purchased 25 artificial red poppies and, pinning one on her own collar, distributed the remainder to the YMCA secretaries with an explanation of her motivation. She viewed this act as the first group distribution of the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy.

Moina Michael hereafter tirelessly campaigned to get the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance. In September 1920 the American Legion adopted the Poppy as such at its annual Convention. Attending that Convention was a French woman who was about to promote the poppy — as a symbol of remembrance — throughout the world.

International Symbol of Remembrance

Madame E. Guérin, conceived the idea of widows manufacturing artificial poppies in the devastated areas of Northern France which then could be sold by veterans’ organisations worldwide for their own veterans and dependents as well as the benefit of destitute French children. Throughout 1920-21, Guérin and her representatives approached veteran organisations’ in the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and urged them to adopt the poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

French Poppy Lady’s Representative Visits the NZRSA

One of Guérin’s representatives, Colonel Alfred S. Moffatt, came to put the case to the Dominion Executive Sub-Committee of the New Zealand Returned Solders’ Association in September 1921 and an order for some 350,000 small and 16,000 large silk poppies was duly placed with Madame Guérin’s French Children’s League.

It was as a result of the efforts of Michael and Guérin — both of whom became known endearingly as the “Poppy Lady” — that the poppy became an international symbol of remembrance.

‘Poppy Day’ – Unique to New Zealand

The Poppy as a commemorative symbol was universally adopted by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand for annual observance of the end of World War 1 – Armistice Day, the 11th of November. The day prior to Armistice Day was designated ‘Poppy Day’ – as it was known from the outset – the day when poppies were distributed for a small donation to aid veterans rehabilitation and support for widows and their families.

The reason New Zealand’s Poppy Day is proximate to Anzac Day and not Armistice Day is one of those quirks of history: the ship carrying the paper poppies from France for Armistice Day 1921 arrived in New Zealand too late for the scheme to be properly publicised, so an NZRSA branch distributed the poppies the day prior to the next national commemoration date which happened to be the 25th April, Anzac Day. That decision established an historic precedence whereby Poppy Day became forever associated with Anzac Day in New Zealand, thus setting it apart from the rest of the world where it is largely associated with Armistice Day.

Poppy Day in New Zealand is now observed on the Friday, one week prior to Anzac Day. It is the day on which the NZRSA conducts its only national fundraising day activity for welfare support of veterans, their widows/widowers and families. The Poppy is obtained by making a donation to street collectors and is worn by men and women on the left lapel, or an equivalent position when wearing a jacket, coat or other.

Poppies are normally worn only on Poppy Day in the military, however for civilians, the practice of wearing the poppy continuously from Poppy Day through to and including Anzac Day, is growing in popularity and to be encouraged.

References:

Dr. Stephen Clarke – Military Historian

Dianne Graves – A Crown of Life: The World of John McCrae (London: Spellmount, 1997)

Moina Michael – The Miracle Flower: The Story of the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy (Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co., 1941)

Adrian Gregory – The Silence of Memory: Armistice Day 1919-1946 (Oxford: Berg, 1994)

Peter Sekuless and Jacqueline Rees – Lest We Forget: The History of the Returned Services League 1916-1986 (Sydney: Rigby, 1986)

W. Tudor Pole – The Silent Road: In the Light of Personal Experience (London: Neville Spearman, 1960

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

PURPLE Poppy – for Animals in War

Australia has now established a similar organisation to Animal Aid called the Australian War Animals Memorials Organisation (AWAMO) but as yet New Zealand has no official ‘animals in war’ charity or organisation to sponsor the manufacture and sale of purple poppies. Wearing home-made purple poppies to acknowledge the animals victims of war by people attending Anzac and Remembrance Day parades, services and associated events is gaining in popularity in new Zealand.

The purple Poppy can be worn alongside the traditional Red one as a reminder that both humans and animals have been – and continue to be – victims of war. The day prior to Anzac Day, 24 April, is designated Purple Poppy Day .

https://www.facebook.com/PurplePoppysAnimalsInTheWar

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

WHITE Poppy – for Peace

Wearing a white Poppy in New Zealand is a relatively recent trend particularly among organisations and individuals who seek to express their pacifist ideals and opposition to all forms of warfare. There is no designated day or particular protocol for wearing this poppy.

Poppy Etiquette

Our only rule is this: wear the poppy with pride, and respect.

“You can pin your poppy in your hair, on your scarf, in your shirt pocket or on your blazer.

Many wear it on or close to Anzac Day, however you can wear it for as long as you like.

As long as you wear the poppy and understand why it’s important, that’s all that matters“

There are widely disparate thoughts regarding Poppy Etiquette however the above is considered entirely inadequate if one is to avoid the potential for personal embarrassment or worse, insulting those honouring the memory of their dead by selecting an inappropriate position to wear your Poppy due to ignorance of accepted practice, protocol and respect.

What really matters!

When worn, the Poppy is an internationally recognised emblem of Remembrance. Accordingly, on the Nation’s two national days of Remembrance, the Poppy as an object should be treated with the respect of that which it represents. It should be worn in a position that reflects our heartfelt respect and honour for our war dead, most commonly on the Left Lapel or above medals when worn. The Poppy should not be treated as a cheap trinket, a symbolic after-thought or fancy dress decoration tacked to any item of clothing in an fashion. By pinning your Poppy onto a scarf, in your hair or anywhere else on your person for that matter (as NZRSA guidance suggests), a position which you may find amusing, fashionable or quirky, does little to reflect the respect or honour for the occasion of Remembrance. Viewed by military personnel and others, your choice of location to wear your Poppy could appear disrespectful or insulting!

The position of one’s heart has never really entered the protocol discussion, this is ‘feel good’ folk-law. It has arisen I suspect due to the common practice of covering the heart with the hat or hand (a means of salute), as a way of demonstrating solemnity at any occasion requiring a show of Remembrance or Honor of the dead.

Wearing the Flanders Poppy

The following etiquette guidance is based upon extensive experience both as a ceremonial and protocol practitioner for our National days of Remembrance, the delivery of same to military servicemen and women, and in my role as an ‘educator’ of the public in my former capacity as a funeral director. The guidance given here is designed to encourage national consistency that is in accord with Commonwealth practice, in the absence of any commitment by the Ministry of Culture and Heritage to issue simple and unambiguous national guidance.

WHO – Anyone may wear a Poppy on an appropriate occasion of Remembrance. It is not appropriate to pin the Flanders Poppy on animals (Purple Poppy, yes). I will not elaborate on the practice of money-making by the using the emblem as an adornment to vehicles, aircraft or buildings (practices I personally abhor) – you must decide on the appropriateness or not for yourselves.

WHERE – The internationally accepted etiquette within Commonwealth countries when positioning a Poppy for wearing, is on the LEFT lapel (or same relative position), or on the left chest (above medals if these are worn). if wearing a Poppy over your heart is significant for you, you should wear it there. Both men and women wear their Poppy in the same position** in spite of differences others might suggest – these exist in folk-law only. If in doubt, have a look at any photograph of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of New Zealand and the members of the Royal Family for guidance – always on the LEFT.

WHEN – On any occasion where you wish to honour or acknowledge the service, sacrifice/death of a serving or former military person at either a public or private occasion, e.g. National days of Remembrance (Anzac Day, Armistice Day, Remembrance Sunday, military days of Remembrance), on Poppy Day (normally the Friday approximately seven days prior to Anzac Day), or when attending the funeral, or a service of Remembrance, for a Veteran or serving military person.

It is common practice in the UK, Canada and some parts of Australia to wear the Poppy for the entire period between Poppy Day and Anzac Day. In general the Poppy can be worn as long as it has meaning for the wearer. All New Zealanders are encouraged to Honour their deceased Veterans by wearing the Poppy for the entire week prior to Anzac Day.

Note: If intending to lay a poppy on a cenotaph/memorial, at a funeral service, grave etc, it is appropriate to use the Poppy you are wearing as the one you lay at the cenotaph/memorial, on a coffin or you intend to place/drop into a grave.

WHAT – It is usual to wear one Poppy only – be it Red (remembrance) or Purple (animals of war) however if appropriate for you, wearing both of the above is entirely acceptable. There is an emerging trend for an Orange poppy to acknowledge Veteran suicide awareness, PTSD and recovery. The “Matilda Poppy” is is an Australian initiative that has yet to see any substantial uptake in New Zealand.

Wearing a sprig of Rosemary whilst predominantly an Australian custom, has its origins as a historically ancient symbol of Remembrance. It was resurrected by Australians for remembering their Gallipoli fallen as Rosemary grew wild on the slopes of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Rosemary is worn in the same fashion as, or in conjunction with, the Poppy.

Wearing a Poppy with medals

WHY – Poppies were the first flowers to appear through the pulverised battlefields in Flanders, first appearing from amongst the graves of fallen soldiers. The vibrant blood red flowers have since become internationally recognised symbols of Remembrance, Sacrifice, Hope and New Beginnings.

When wearing medals, it is appropriate to wear the Poppy immediately above the medals, or on the left lapel. If wearing the medals of a deceased relative on the right side, the Poppy is remains on the LEFT side. When attending a commemorative occasion or funeral where poppies are to be laid as a tribute, positioning your Poppy on the left side – lapel or above medals – permits ease of access to remove it at the appropriate time to either place at the memorial, on a coffin, at a graveside, or drop into the grave.

There are also a few practical reasons for favouring the LEFT, such as: the right lapel is currently designated for military Commendations and Citations and the NZRSA membership badge. The Year of the Veteran Badge is also recommended (above) for wear on the right lapel, as are name badges. This then suggests the left lapel is likely to have more free space to accommodate an uncluttered Poppy, it is appropriately positioned if miniature medals are also worn (usually attached to the LEFT lapel), and the left side eliminates conflict with a driver’s safety belt.

HOW – You are honouring the war and military service dead. Wear your Poppy with dignity and pride; treat it respectfully. Ensure it is in the upright position and not askew, twisted, dirty, petals bent, the paper RSA tag scrunched up, torn or folded. Your Poppy should look pristine and befitting of a symbol of Remembrance.

‘Remember why and for whom you wear your Poppy’

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Notes:

Defence Force Personnel.

Military Variations. RNZN personnel generally conform to the protocol above, i.e. Poppy worn on the LEFT side. The NZ Army is the only Service to wear a Poppy on their uniform head dress – behind the beret badge, or inserted into the LEFT side of the Puggaree of the Mounted Rifles headdress and ceremonial ‘Lemon Squeezer’. The RNZAF wear a Poppy on the RIGHT chest, the origins being that the Flying Badge (wings) or an aircrew brevet is worn on the left and therefore not to be obscured.

Ode of Remembrance

The Ode of Remembrance is an ode taken from Laurence Binyon’s poem For the Fallen which was first published in the “Winnowing Fan; Poems of the Great War” in 1914. It also appeared in the The Times in September of the same year.

‘For The Fallen’ composed here; The Rumps promontory beyond

The poet wrote For the Fallen, which has seven stanzas, while sitting on the cliffs between Pentire Point and The Rumps in north Cornwall, UK. A stone plaque (above) was erected at the spot in 2001 to commemorate the fact. The plaque bears the inscription:

FOR THE FALLEN

Composed on these cliffs, 1914

There is also a plaque on the beehive monument on the East Cliff above Portreath in central North Cornwall which cites that as the place where Binyon composed the poem. A plaque on a statue dedicated to the fallen in Valleta, Malta is also inscribed with these words.

The poem honoured the WW1 British war dead of that time, and in particular the British Expeditionary Force, which by then already had high casualty rates on the developing Western Front. The poem was published when the Battle of the Marne was foremost in people’s minds.

Over time, the third and fourth stanzas of the poem (although often just the fourth), were claimed as a tribute to all casualties of war, regardless of state.

(3rd stanza)

They went with songs to the battle, they were young.

Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

(4th stanza)

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

(5th stanza)

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England’s foam.

The final line of the Ode, ‘We will remember them’ is usually repeated in response by those listening. The phrase ‘lest we forget ‘ is often added by the person reciting the Ode as a final line after the Ode response.

The Ode of Remembrance became the Australian Returned Services League Ode, and had recited at memorial services held on days commemorating World War I, such as Anzac and Remembrance Days. In New Zealand’s numerous RSA’s, it is read out nightly at 6 p.m. The Ode is also part of the Dawn Service at 6 a.m. After the Ode of Remembrance has been recited, it is often followed by the playing of the ‘Last Post’, observance of a Minute of Silence, followed by the ‘Rouse’ (mistakenly called ‘Reveille’, a different and longer piece of music).

NZ Tomb of the Unknown Warrior

The New Zealand Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is located at the National War Memorial in Buckle Street, Wellington. The remains of the Warrior, one of the 18,166 New Zealand casualties of World War 1, were exhumed on 10 October 2004 from the Caterpillar Valley Cemetery in France, near where the New Zealand Division fought in 1916.

History

On 6 November 2004 the remains, in a copper coffin sealed and placed in a rimu coffin brought from New Zealand, were handed over from the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to a New Zealand delegation during a ceremony at Longueval, Somme, France. The Warrior arrived in New Zealand on 10 November 2004. While he lay in state in the Parliament Buildings an estimated 10,000 people paid their respects. The Warrior was laid to rest on the 86th Armistice Day, 11 November 2004, after a service at St Paul’s Cathedral, Wellington and a 2.85 km slow march procession through the streets of Wellington, lined by about 100,000 people. The Tomb was sealed with a bronze mantel at 3:59 pm, bearing the words:

“ An Unknown New Zealand Warrior

He Toa Matangaro No Aotearoa ”

The Warrior is one of more than 1500 New Zealanders killed on the Somme battlefields in France. Most of them, 1272, remained unidentified and are buried in unmarked graves or remembered on memorial walls. The remains are thought to include an almost complete skeleton, and other belongings that established beyond doubt the Warrior’s nationality.

Medals & Awards

The Warrior was awarded:

- The 1914-15 Star for service between August 1914 and December 1915

- The British War Medal for service during World War I up to 1920

- The Victory Medal

- The 1939-1945 Star for service during WW2

- The New Zealand Operational Service Medal

The Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association also awarded its Badge in Gold, the first time it has been awarded posthumously. Each RNZRSA District President placed soil and other items into the Tomb to acknowledge the service personnel from their districts who had given their lives to the nation, including soil from the farm of Capt. (Rtd) Charles Hazlett Upham, VC and Bar. Soil from Caterpillar Valley Cemetery was provided by the Ambassador from France.

NZRSA – Daily Act of Remembrance

In RSAs across New Zealand, a simple and solemn ceremony known as the ‘Remembrance Ceremony’ is enacted each night at 1800 hours (6 p.m.) to acknowledge and pay our respects to “The Fallen”, pledging they and their sacrifices will never be forgotten.

The ceremony starts with the lights being dimmed (sometimes a small memorial light will be illuminated) after which the Ode of Remembrance is recited. After the last line of the Ode, all present respond with – ‘we will remember them’. Although not strictly correct, some may also follow this response with –‘lest we forget‘ – after which the lighting is restored and activity resumes.

NZ Ensign – Flown at Half Mast

Origin – The half-mast tradition has developed important meaning over time, but its exact origins are a little unclear. Many historians point to a British expedition to Canada in 1612 aboard the ship Heart’s Ease. The Captain, James Hall, was killed by an Inuit spear, and the crew lowered the ship’s flag to half-mast. This may have been an agreed distress signal to those who had gone inland that something had gone wrong, but sailor superstitions may also have had some influence. According to tradition, the ship’s flag was put at half-mast to make room for the invisible ‘Flag of Death’. In fact, when the ship returned to London, the ship’s flag was still at half-mast, implying that the crew was still sailing under Death’s flag.

Whatever the origins, the tradition became more widely embraced over time, particularly by sailors. One of the first accounts in American history is from 1799, when the Navy Department ordered all of its ships to lower their flags to half-mast upon the death of George Washington.

Times of Respect & Mourning

The New Zealand Ensign is usually flown at the masthead (or the ‘peak of the gaff’ on RNZAF bases) during daylight hours, or for the duration of a ceremony, e.g. a commemorative occasion. The Ensign is half-masted to acknowledge the death of distinguished leaders of the nation, or at ceremonies of remembrance when the dead are being honoured such as on the days of national remembrance, Anzac and Remembrance Days. At funerals, a half-masted NZ Ensign is a mark of respect for the deceased service person. It may also be acknowledged by a half-masted flag at the Veteran’s parent RSA.

The method of bringing a flag to half-mast position if the flag is already flying, is to lower the flag directly to the half-mast position – at least one flag-length (the depth of the flag) below the masthead, or lowered to such a position so as not to be confused with a flag that has merely slipped from the masthead because of loose halyards. The half-mast position will depend on the size of the flag in relation to the length of the flagpole.

To raise the flag to a half-mast position from the bottom of the flagpole, i.e. when first clipped to the cleats, the flag is first hoisted to the masthead and then lowered to half-mast as detailed above. At the end of the day or period of morning, the flag is first hoisted to the masthead and then lowered all the way down for removal.

When the New Zealand Ensign is flown at half-mast, no other flag should be flown above it.

Other Symbols of Remembrance

“It was magical when flowers appeared on the upper reaches – not that we saw much of the upper reaches. But when we did, we were reminded of home when spring clothed the hills with flowers. The dead lying among them seemed to be asleep.”Source: Extract from ‘Gallipoli Peninsula’ by Alastair Te Ariki Campbell.

- Remembrance Rose

In 1925, the Wellington RSA instituted the inaugural “Rose Day” which raised funds for the Wellington Citizens’ Memorial. In later years many RSAs held their own Rose Days in order to raise funds for many community as well as RSA projects (and in contrast to the Poppy Day Appeal that was solely for the welfare of returned service personnel and their dependants in need). By 1944, the Dominion Council of the NZRSA was encouraging the holding of Rose Day on a nationwide basis on the Friday before Armistice Day.

The blood red Remembrance Rose was developed as an initiative of the NZRSA some years ago and can be purchased from most good garden centres.

- Gallipoli Rose & Rosemary

The official symbol for the 100th Anniversary of the Gallipoli Landings held on Anzac Day 2015 at a commemoration service in Turkey, was the Gallipoli Rose backed by a sprig of Rosemary.

Whilst the red Poppy was generally the first flower to appear out of the pulverised surface of the battlefield, the so called Gallipoli Rose, or cistus salviifolius, is one of the Spring wildflowers that carpets the slopes and hills of the Gallipoli Peninsula, from April to May. It is believed that soldiers at Gallipoli during the First World War were so taken with its beauty that some took seeds home and planted them as a symbol of peace and remembrance.

- Wild Rosemary

Wild rosemary, also found on the Peninsula, is an ancient symbol of remembrance and is often intertwined with leaves and flowers in wreaths of remembrance, and pinned to lapels on Anzac and Armistice Days.

In 1915, a wounded Australian soldier was repatriated to an army hospital in Adelaide. He brought with him a small rosemary bush he had dug from Gallipoli and planted it in the hospital grounds. Later, cuttings were taken to grow into a hedge, and plants from that hedge are still thriving today in the Waite Arboretum at the University of Adelaide.

As New Zealand poet Alastair Te Ariki Campbell writes in his poem “Gallipoli Peninsula”, the wildflowers provided comfort to the soldiers, half a world away from home:

“It was good to feel,

during such moments,

that we were human beings once more,

delighting in little things, in just being human.”

Sources: Wikipedia

Extract: ‘Gallipoli Peninsula’ by Alastair Te Ariki Campbell.

Reference: “Ode of Remembrance.” Fifth Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment official website. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

National Centennial Commemoration of World War 1 (28 July 2014 – 11 November 2018)

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1914, thus precipitating World War One, New Zealand’s first involvement resulted from a request from the British High Command. Germany had a well established wireless station in Apia, the then capital of German Samoa. New Zealand was requested to capture the country. Eighty Germans and a gun boat were no match for the 1,374 men of the NZEF Samoan Advance Force who landed (unopposed) on 29 August, 1914 and took over control of the country.

The Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force departed New Zealand for England with the Australian Imperial Force on 16 October 1914, to prepare themselves to support the British Expeditionary Forces in France and Belgium and stem the advance of the Germany Empire across Europe. As we now know, the New Zealanders were directed by the War Office to divert to Egypt as Turkey, who had pledged its support to Germany, entered the war … Egypt, and later the Gallipoli Peninsula, became New Zealand and Australian forces revised destination.

‘Fields of Remembrance’ consisting of white wooden crosses with the name of every New Zealand soldier, sailor, airman and nurse who went to the “Great War” as it was known, were established nationwide in the vicinity of town cenotaphs and memorials, and remained in place for the four years of commemoration.

The most significant commemorative event for New Zealand and Australia during this period began on the 25th April which marked the 100th anniversary of our two countries storming ashore at Anzac Cove, the Gallipoli Landings on this date in 1915. During this past four year period, numerous commemorations have taken place both in New Zealand and around the world to remember and honour those service men and women who participated, fought, were killed or died, as well as those who returned, many ‘broken’ from the experience. The commemoration ceased on Armistice Day, 11 Nov 2018.

Dolores Cross Project (DCP)

The DCP relies upon volunteers (essentially anyone travelling overseas for business or pleasure who are able to assist) to pay a personal tribute to each fallen man or woman by placing a Dolores Cross on war graves they are able to visit. For more information:

Visit the Dolores Cross Project or follow it on Twitter & Facebook

Source: Kindly authorised by Dolores Ho – Archivist, National Army Museum, Waiouru

~~~~~~~~~~<< MRNZ >>~~~~~~~~~~