~ 500 ~

The return of this medal marks a new milestone for MRNZ, the 500th returned to families 🙂

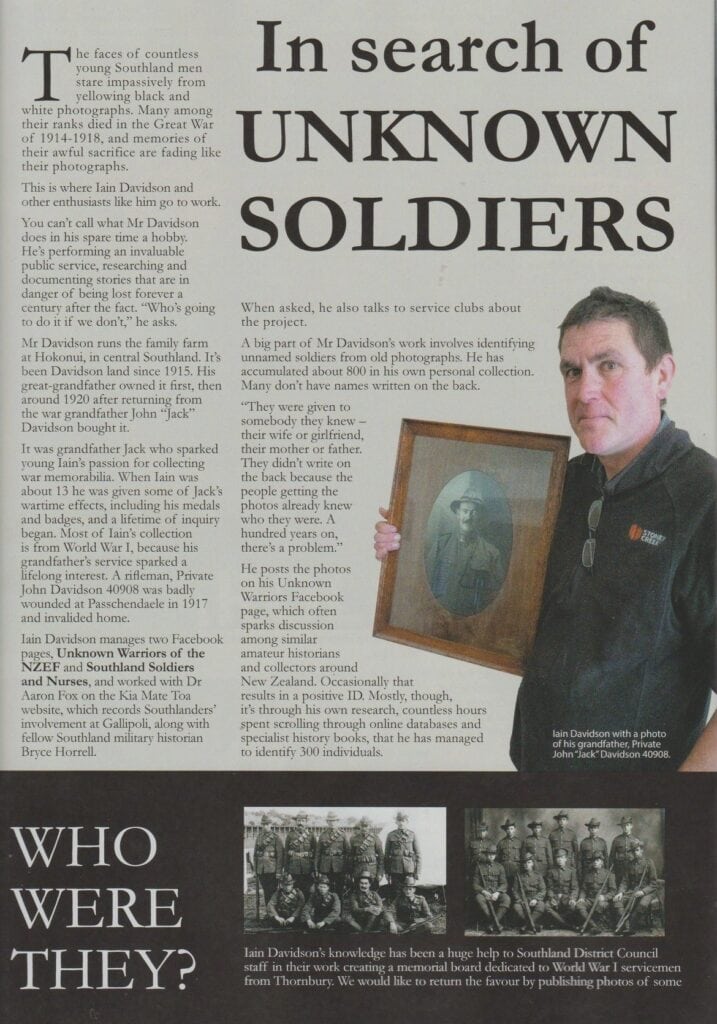

Vale – Iain “Puk” Davidson

Hundreds of these photographs have turned up through the decades but because they were nameless and nobody knew who they were, many have been and still are discarded. Iain was their champion! He rescued every picture he could lay his hands on from those he spotted on the internet and from collectors. Iain’s work in this regard will be greatly missed however his legacy will live on in the many hundreds of NZEF soldiers and nurses he has successfully identified and have now been included in five volumes (to date) published by the Onward Project.

Apart from the photograph project, Iain’s interest in military badges, medals and ephemera was never far from his mind and had led to my first meeting with Iain. In March 2017 an article appeared in a Southland newspaper that inviting descendants of a soldier named on a ‘Death Penny’ that was found in a house in Milton, to come forward and claim it. When nobody claimed the plaque, Iain contacted me to see if MRNZ would be able to trace the family. Within 20 minutes I had a name and had made a phone call to have the Memorial Plaque returned to a descendant family member in Invercargill. Impressed with our speed in resolving his query, Iain has since collaborated on a number of similar cases, all of which have had successful outcomes.

A generous gesture

In late September 2023, two months before his passing, Iain had been in contact with James, an ex-patriot Kiwi militaria dealer who lives in France. Iain being a collector of NZ regimental badges, his association with James has extended over several years with many items Iain has wanted were able to be source for him. During their last contact, Iain had routinely intended to see if anything in the trader’s on-line shop took his fancy. While nothing in particular had caught his eye this time, on the spur of the moment he decided to buy one of the NZ medals that James had on offer. While not a collector of medals, Iain noticed that one of the medals had an uncommon name impressed on it which belonged to a World War 1 soldier from Otago. So he bought the medal with the intention of returning it to the soldier’s descendants.

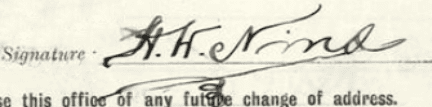

While Iain was not a collector of medals and not normally engaged with returning militaria to families (although he had on several occasions), I asked him what had prompted him to return the Victory Medal named to 58916 PTE Horace Wise NIND? He said “I have been trading/swopping info with James (France) for a number of years, and while we have never met we have struck up a friendship. Good question – why did I choose Horace’s medal? I could have taken the cash option, but in this day and age I thought instead of that, I will get items from his shop. I looked over what was on offer but there wasn’t anything much that struck a chord with me. Horace was from Central Otago and I do have an affinity to the place, though loosely.” (Iain was five years old when he and his mother left the family farm and went to live in Alexandra).

Iain had selected the Victory Medal purely on the basis that it was named to a First World War soldier from Otago, a region of sentimental interest. As he further explained, he was always very grateful for the selfless help others had given him with his projects, whether with the nameless photograph research or helping to build his collections through swaps and purchases. He said to me, “I would also like, and this is only a token, to repay with generosity, what I have received from others in the past.”

Research assistance

October can be a very busy time on Otago farms. Iain was flat out lambing and managing his stock etc whilst waiting for the medal and some badges he bought, to arrive from France. He had already done some ground work on Horace Nind and had received several pieces of information from a regular contributor to his photograph research. ‘Joanne Sunbeam’ had provided Iain with a number of Ancestry.com documents that could help locate Nind descendants. Being short on time to conduct the analysis and search for a Nind descendant to pass the medal to, Iain contacted me for assistance and sent me what paper work he had collected.

I began with the obvious and started looking for Nind descendants in Otago and Southland in the areas Horace and Annie had lived. While I found no shortage of connected females, within a couple of hours I had managed to isolate what I believed was the only Nind male living in the Oamaru/Waitaki area that looked particularly hopeful. Horace and Annie’s three children had all married, the Nind’s becoming grandparents to seven grandchildren (six females, and only one male!), all of whom are still alive today.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Emigration from Surrey

“Nind” is not a particularly common name in New Zealand however once you start looking in the right places, there are quite a few, some of who will no doubt be linked to the Nind families from Otago. To locate the descendants of Horace Nind, I began with his family tree to get a feel for the family’s centre of gravity which proved to be Central Otago.

Horace Nind’s grandparents Henry William NIND (1833-1925) and Hannah DUKE (1839-1908) were Assisted Immigrants from Surrey who had emigrated from England with seven children ranging in ages from 12 years to five months. Henry Robert Nind (1865-1946), Horace’s Nind’s father, was just nine years of age when the Nind’s landed in NZ. The cost of the family’s passage on the Buckinghamshire was the princely sum of £79 (pounds). The Buckinghamshire left London on 7 March 1874 and arrived at Port Chalmers on 29 May, a voyage of 83 days which was fast compared with the average voyage length of 90-105 days. Following the family’s quarantine period at the Caversham Immigration Barracks, Henry W. Nind settled his family in Caversham. A Printer by trade, Henry soon had himself immersed in the business within the Dunedin community. While living in Dunedin the Ninds also increased their family size by eight more children, only five of whom survived to adulthood, which prompted their move to a more commodious residence on the Esplanade at St Clair.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Horace Nind’s family

In July 1889, Henry Robert Nind (22) married Horace’s Dunedin born mother, 22 year old Isabella WISE (1865-1922) at Caversham. A family of six children followed: Gladys Maud (Nind) McDONNELL (1890-1967) formerly JACKSON (dec), Henry William Nind Jnr. (1893-1894), Horace, Violet Duke (Nind) KINRAID (1896-1967), Harold Albert Nind (1901-1977) and Eric Wallace Nind (1909-1986).

Horace Wise Nind was born in Dunedin on 12 December 1895. After his birth, the Ninds moved from Dunedin to a farm and mining settlement of Galloway in Central Otago. Galloway sits on the east bank of the Manuherikia River, 6.5 kilometres north-east of Alexandra. It was home to many miners working the bucket gold dredges in the Manukerikia River as well as the Clutha, and various land leasers attempting to establish farms. Unfortunately the Galloway School which had opened in 1894 in a room in the Galloway Railway Station, closed two years later due to a scarlet fever scare. An alternate room was made available in the Springvale Bank of NZ until a new school was built in 1912. Whatever Horace’s early schooling situation is not known by this author (possibly the Springvale and/or Clyde schools?) however it may well have been the inspiration for his eventually becoming a School Teacher, a career he started at Clyde. Horace (19) had become a trainee teacher while attending the Clyde School until the First World War intervened in 1914.

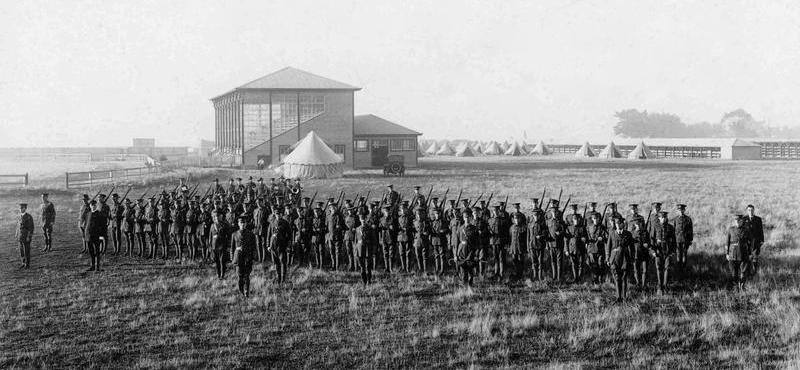

14th (South Otago) Rifles Regiment

Being a single man of eligible fighting age in late 1915, Horace compulsorily registered for military service at Clyde in July 1916 with the 14th (South Otago) Rifles Regiment with whom he began rudimentary military training. In anticipation of his going to France he had received advice from his Area Officer at Ranfurly to report to the Oamaru Group HQ in October 1916 to begin the process of attestation before going to Trentham Military Camp. Horace being only a trainee at that point was due to undertake his Teaching Certificate Examination in January 1917 and so advised the officer that he would be unable to seek leave from the Otago Education Board (OEB) until Feb 1917.

As enlistments were only taken for two drafts ahead, Horace was advised by the Area Officer to report back in Jan 1917 after his exams, to confirm his availability for February. In the interim Horace was medically examined at Clyde without any issues – he was Fit to enlist. As his exams approached Horace sought and received approval from the OEB for leave to enlist in February 1917. Accordingly he wrote to the Army’s Group Office HQ in Oamaru and gave them the details. To his consternation he heard nothing further! Horace’s greatest concern was continuity of his income. Once he physically took leave from the OEB, he would no longer be paid by them. Despite more questions and waiting, no answers were forthcoming from Oamaru. By March 1917 Horace was in dire straits.

The inconvenience of not receiving any reply or information from the Group Office HQ meant not only was he unable to plan ahead, but was almost broke! The inconvenience of not being advised what was (or was not) happening re his enlistment forced Horace to burst into print to none other than the Minister of Defence. He outlined his circumstances saying he had made appropriate arrangements with his Area Officer in anticipation of being called up in February. Horace explained that the delay in his enlistment and therefore his stretched financial circumstances was causing him some difficulty in maintaining himself. He was technically unemployed! The delay in his enlistment was also causing him a good degree of personal embarrassment since he had received several presentation gifts from the school in anticipation of his departure overseas.

The urgency of the situation could be summed up in the rather succinct last line of his letter to the Minister “… If I had been called up in February it would have been alright, but it is not my fault and I can’t live on air.” Unfortunately Horace had overlooked one small detail. He had agreed to advise his Area Officer at Ranfurly when the OEB would release him for service – this he did not do but had advised the Group Office HQ in Oamaru directly. No doubt thinking that by communicating this information directly to the Group Office, the enlistment administration would be expedited and accordingly there would be no break in his income. However, his enlistment documentation had remained in Ranfurly pending his reply to the Area Officer. The Area Officer in Feb 1917 was absent attending several weeks of training and so Horace’s paperwork could not be processed until the officer returned. This confusion meant Horace remained unpaid for the best part of three months and his enlistment delayed until after the 1st of May, 1917.

Enlistment at last!

58916 Private Horace Wise Nind had just turned 21 years of age, was described as 5 feet 3 inches (160 cms) tall, and weighing 9 stone (57 kgs) when he reported to the camp at Alexandra on 2 February 1917 to begin enlistment. The delay also meant that instead of his preference to join the Otago Infantry Regiment’s 26th Reinforcements (on his original enlistment application), he was drafted into the 29th Reinforcements.

The Reinforcements were concentrated at Trentham Camp in May 1917 for a period of induction and then to the Featherston Training Camp for infantry skills training. Pte. Nind embarked with the 29th Reinforcements left Wellington aboard HMNZT 92 Ruahine on 15 August 1917. He marched into NZ’s Sling Camp in Wiltshire on 3 Oct 1917 to commence training in preparation to join his regiment at the front. Before moving to France from Egypt, the Otago Regiment had been reorganized into two battalions, the 1st and 2nd Battalions as part of the recently formed New Zealand Division. Pte. Nind was assigned to the 1st Battalion which was part of the NZ Division’s 1st Infantry Brigade. The 2nd Battalion joined the 2nd Infantry Brigade, effectively splitting the Otago Infantry Regiment in two. Each battalion was made up of four rifle companies, each with around 227 men.

Into the field …

Pte. Nind arrived in France from England in what was to be the final weeks of the war. The first stop on 30 Sep 1918 was the NZ Infantry and General Reserve Depot located within the Etaples Depot Camp. Posted to No.4 Company, 1st Battalion Otago Infantry Regiment (1/OIR), he joined his battalion in the field on 14 October.

In August 1918, the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ commenced when the Allied armies broke through the heavily-defended German Hindenburg Line and began advancing east and northwards. While the NZ Division had taken a fearful beating during the Battle of Bapaume (31 Aug-3 Sep), the 4th Company of 1st Battalion Otago’s alone lost over 50 per cent of its initial strength in casualties. The NZ Division was then rested giving the battalion time to recover and re-build its strength with the arrival of fresh reinforcements.

Final advance

As the offensive continued to gather pace throughout August and September, the German Army had shown signs of being demoralised and inclined to withdraw however it was far from a defeated army. As the Allies pressed, mobile artillery gave them the upper hand in maximising the use of this destructive firepower while the German artillery was much less flexible and paid the price accordingly. German resistance the Divisions encountered however was savage, particularly from well prepared machine-gun posts.

By the beginning of November, the NZ Division was preparing for a major offensive which became known as the Battle of the Sambre. Three divisions, the British 37th and 62nd and NZ Division were to advance the Allied line to the north and west, capture or destroy German divisional artillery, and ensure Le Quesnoy did not hinder or divert the advance the Div to its final objective, the Forêt de Mormal (Mormal Forest). The limit of exploitation was the River Sambre, a total distance from the NZ Div’s Start Line of around 35 kilometres.

The attack formation was essentially an extended line of Divisions. The NZ Div’s front line would be manned by the four battalions of the NZ Rifle Brigade which would have a 2.5 kilometre frontage. While a good proportion of the NZ Div would encounter Le Quesnoy which lay about seven kilometers ahead of their Start Line, the town was not to be destroyed as there were some 1600 French citizens who had been held hostage in the town since it was occupied by a German garrison in August 1914. Supporting artillery for the attack on Le Quesnoy would be confined to the use of shrapnel rounds on the ramparts and the use of smoke shells. The 1st and 2nd Otago Battalions, being two of the four NZ Infantry Brigade battalions, were directed to by-pass Le Quesnoy and prepare to clear the Mormal Forest that lay beyond.

Battle of the Sambre / Capture of Le Quesnoy

At 05.30 on the morning of November 4, massed artillery brigades initiated a massive creeping barrage behind which were thousands of Infantrymen. As the NZ Div advanced they encountered entrenched positions of opposition, particularly of enemy machine-gun posts that were able to inflict significant casualties.

The day proved to be one of extraordinary successes for the New Zealand Division. The results from the opening day of the battle had been an advance of over 9.5 kilometres, the capture of Le Quesnoy, Rompaneau, Villerau, Potelle, and Herbignies (thereby liberating many French civilians), with nearly 2,000 prisoners taken, over 70 howitzers and field guns (many of them complete with gunners, drivers and horses) plus a formidable number of machine-guns and trench mortars.

The Otago Regiment’s last action of the war began the following day, 5 November in the Mormal Forest. The Otago’s together with troops assigned from the rifle brigade began the clearance of Mormal Forest from West to East. For the 1st Battalion, aside from sporadic pockets of resistance, their advance through the forest was made more difficult by the dense undergrowth, persistent rain and exploding artillery shells among the tall trees. Their advance was bought to a halt when they reached the middle of the forest. A German machine-gun strong point sited in what became known as the Forester’s House, Mormal engaged the advancing troops, and were backed up by reserves positioned on the high ground behind the house. An initial attack by the Otago’s failed, but the house fell at the second attempt with two machine-guns and 30 prisoners captured. The brigade’s 2nd Otago Battalion established its headquarters in the house while the 1st Otago Battalion after regathering themselves, pressed on with the clearance. By 1.30 p.m. the Infantry Brigade’ last objective had been completed, and by 3.00 p.m. a halt was called and a defensive line formed. In spite of the heavy going, the opposition encountered and artillery fire in the forest, the action in the forest had resulted in the deaths of only two Otago officers and nine soldiers, a small toll given the significant distance they covered. These men were among the last New Zealanders killed in the war.

Reserves arrived during the hours that followed and the Otago battalions marched the 14.5 kilometres back to Le Quesnoy which had been liberated the previous day without the usual pre-attack artillery destruction of the town. The 4th Battalion, NZ Rifle Brigade had scaled the town’s 13 meter high medieval ramparts via a single ladder, and captured the town without the loss of a single French citizen’s life. It was while at Le Quesnoy the Otago Regiment received word of the Armistice on November 11, thereby officially bringing the war to an end. The news was met with no fanfare or celebration. The men were somewhat indifferent to the event and just carried on, showing little interest.

After nearly three years of war in France and Belgium, the New Zealand Division’s campaign on the Western Front was finally over. With perhaps 500 New Zealanders killed while serving in Imperial units, including the naval and air forces, New Zealand’s death toll on the Western Front approached 13,000.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Armistice – Army of occupation

Under the conditions of the Armistice, Germany had 14 days to evacuate from all remaining occupied territory – as well as from German territory claimed by France and Belgium. The Allies quickly sent their armies to occupy the Rhineland to ensure that Germany could not break the ceasefire. Most of the New Zealand Division was billeted at Beauvois and Fontaine when they heard news of the Armistice. But their work was not yet done.

Sent to join the British occupation forces in Germany, on 28 November the NZ Division began a 240-kilometre march towards the German border. On 1 December, in Bavais, King George V and Edward VIII (then Prince of Wales) attended a Church Service with members of the Otago Regiment. The Regiment then continued their march, reaching the German border on 20 December 1918 where they were entrained, and marched to the New Zealand Division’s area of occupation at Mulheim, Cologne.

The liberated French and Belgians enthusiasm for their arrival was overwhelmingly thankful and friendly, while the Germans were subdued, possibly afraid, but not openly hostile. The occupation of the Cologne Bridgehead involved additional duties of maintaining guards over German war material and factories, and the supplying of picquets and Regimental guards. No resistance was encountered and the soldiers stationed in Cologne later reported that the German inhabitants were in the main friendly and civil towards them.

The Regiment’s main duties during the occupation of Germany was guarding war supplies and clearing mines. During the month of January the Regiment was employed in the mornings on educational training under the Divisional Education Scheme; in the afternoons recreational games were played. River excursions on the Rhine always were popular. The occupying of battle stations in defence of bridgeheads, factories, railway stations, and public buildings was practiced in view of possible civil disturbances, and was certainly impressive from a military point of view.

The New Zealanders’ role as occupiers was short-lived. Once it became clear that Germany could not resume the fight, attention turned to demobilising the troops and getting them home. Beginning in late December, married men and those who had enlisted in 1914/15 were returned to England and after demobilisation, shipped home to New Zealand. This process sped up from January 1919, as ship transport resources were freed up with 700–1000 men leaving each week.

On 4 February 1919, due to thinning ranks as men were sent home, the Otago Regiment was consolidated into a single battalion. The Otago Battalion was amalgamated into the South Island Battalion on 27 February. On 25 March, the last New Zealand soldiers left Cologne at which time the New Zealand Division was officially disbanded. By the beginning of April the South Island Battalion had left Germany.

Sources: NZ Electronic Text Collection (Victoria); NZ History.govt.nz; Wikipedia; Le Quesnoy: NZ’s Last Battle 1918 by C. Pugsley; MFAT.govt.nz

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Home again

Being a late reinforcement for the battalion, Pte. Horace Nind did not leave England until 02 July 1919. In the interim his demob Medical Board had diagnosed a number of his hospitalisation since arriving in France as being attributable to CPDI – Chronic Pulmonary Disease Indeterminate. Horace’s symptoms and his lungs showed early signs of Tuberculosis not yet fully manifested fully into the disease. The finding however ruled him out of any further war service and would be invalided back to NZ. Pte. Nind left Liverpool on HMNZT 273 Somerset on 02 July and arrived at Wellington on 21 August, 1919. Soldiers who were not hospital cases were permitted several weeks of home leave. For Horace this meant his leave would last only until he was required to be admitted as an In-patient at the Dunedin Hospital on 10 September. Still subject to the obligations (and orders) of the NZEF, Horace had to undergo a detailed re-assessment of his health. After two days of being poked, prodded and eyeballed by the medical staff, he was released on transfer to the Clyde Hospital as an Out-patient where his lungs could be monitored. I also meant he could now be released from the Army. Horace Nind was discharged from the NZEF on 28 November 1919 being “no longer physically fit for war service on account of illness contracted on active service.”

Medals: British War Medal, 1914/18 and Victory Medal

Service Overseas: 2 years 6 days

Total NZEF Service: 2 years 300 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

School Master

Returning to Clyde School as a trainee teacher, Horace now 26 passed the necessary examination credits to begin a limited license teaching career in November 1922. In 1923 Horace moved to Galloway to live and where his family was domiciled, whilst taking up a teaching appointment at the Chatto Creek School – about 15 kilometres north of Galloway. He remained here until gaining his first promotion in 1924 as Headmaster at the Beaumont School, which while still in the same valley, was 100 kilometers in the opposite direction south-east of Roxborough. In May 1926, Horace was appointed Headmaster of Waikouaiti School, an east coast settlement some north of Dunedin. This post he remained at for the next 30+ years.

Eighteen months after his arrival at Waikouaiti, Horace was married to Dunedin born Annie Campbell PATTERSON (1904-1987) at Milton on 28 Dec 1927. The Ninds had the first of three children two years later, Graeme Patterson NIND (1930-2012) followed by Margaret Isobel [Nind] DALE (1934-2019), and finally Bryan Henry NIND (1936-1996). Throughout his teaching and school administration career, Horace Nind was considered a popular master and well liked in the communities he served. Approaching the end of his teaching career, Horace’s final appointment was as head of the Waimate School. This post took him through to the retirement age of 60 in 1955, the Public Service’s then mandatory retirement age and eligibility benchmark for a pension.

Horace and Annie retired to their home in Point Bush Road, Waimate where Horace saw out his final days. He passed away at 149 High St, Waimate on 22 February, 1966 at the age of 70 and was buried in a soldier’s grave at the Waimate Cemetery, North Otago. Annie Nind died almost 20 years later before joining Horace.

‘Lest We Forget’

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On the Nind trail …

A phone call to David Nind confirmed I had found Horace’s descendant. An Oamaru resident, David is a former software support group for the policy and regulatory stewardship of Inland Revenue (way above my intellect and pay grade!). Sadly he never met his grandfather Horace as he (Horace) had died the year before David was born.

David recalled a story of Horace (semi-jokingly) telling his sons that the first of them to produce a grandson and name him “Horace” would receive £50 (pounds = about $100). Given the bevy of females that Horace’s sons had fathered, David considered he was lucky to have escaped with the name he has!

However, David’s respect for his late grandfather in surviving the First World War, and his post war success in the education field, was clearly a source of pride to him and in the manner of which he spoke of Horace. Apart from a few photographs of Horace and the family, David’s only treasured memento of Horace’s war service is his identity tags (‘dog-tags’) he wore in France.

After chatting with David, I confirmed with Iain Davidson my findings and that David was the most appropriate descendant to receive Horace’s medal. David was also the only male of his generation in the immediate family and, as is desirable when determining a descendant to receive a returned medal, he is able to maintain continuity of the medal recipient’s family name thereby giving greater relevance to being the custodian of such a medal.

Iain later emailed me to say he had made contact with David and advised him that Horace’s medal was on its way to New Zealand. David was excited at the prospect of having something more meaningful of his grandfather’s war service to add to the dog-tags. When I asked if David could ever recall seeing Horace’s medals, David could not recall seeing them as a child however David’s sister (one year older than David) was able to confirm that the medals used to be kept in a tin and that she would often play with them! Regrettably it would seem that David’s father may have had an urgent need for funds in the early 1970’s which David and his sister could only conclude this to be the most likely reason the medals left Nind family ownership.

Throughout October and early November, I checked back with Iain for progress updates on the medal’s arrival as it was to be my que to publish this story. No luck – the medal hadn’t arrived when last we spoke but he would call me as soon as it did. Iain then headed off on his fishing expedition to Haast in late November and the rest, as they say, is history.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Giving back …

The news of Iain’s sudden passing (result of a medical event) on November 14, 2023 at the age of 56 stunned all who knew him. Advice was quickly circulated via Iain’s website “Unknown Soldiers of the NZEF”. After a couple of weeks, I felt David had better be put in the picture as there was always the possibility the medal had gone astray in route from France. I contacted Iain’s wife Kathryn to explain the situation to alleviate any concerns she may have with what to do with a parcel from France that she would probably know nothing about, nor what to do with it. Iain understandably was unlikely to have left any instructions for this non-priority delivery. Kathryn most gracious thanked me for the advice, confirming she had no idea what Iain’s intent for the medal was. At least I was able to solve one small problem she would no longer need to be concerned with. I left David’s address and contact details with Kathryn for future reference, and who was only too willing to ensure the medal, if or when it did arrive, would be sent on to David.

On December 9th, 2023 I received an email from David Nind to advise that he had received Horace Nind’s Victory Medal from Iain’s wife Kathryn. Despite the sad circumstances that surrounded Iain’s last act of benevolence for an Otago soldiers descendant family, he would be very pleased to know his wish for Horace Nind’s medal has been fulfilled by its return to Nind family ownership. Iain’s one concern was for the missing British War Medal 1914/18 that had been issued with Horace’s Victory Medal. He hoped it had not been melted down (as many had been due to the silver content) and that it may someday be found and returned to David.

Thank you Kathryn for completing this medal’s journey. I can think of no better occasion to acknowledge the return of our 500th medal than to be Iain’s gift of Horace Wise Nind’s medal to his grandson David.

Iain – your work is done, we shall miss your friendship, expertise and contributions to preserving our military history. R.I.P “Puk”.

The reunited medal tally is now 500.