Ruth and her second cousin Mike live in the Christchurch area. In August 2019, Mike received an unexpected email from a distant relative who lived in Australia. The well-meaning relative had received a trio of World War 1 medals (below) she believed had belonged to their family. These were the medals of a New Zealand infantry soldier, Alexander Sinclair whom the family knew as “Uncle Alec”– actually he was great-uncle Alec to Ruth and Mike. Thought to have been lost to the Sinclair family many years ago, Ruth and Mike were of the belief that after Alec’s sudden death in 1980, the medal were thought to have been taken to Australia by relatives of Alec’s wife who had also sadly died within days of her husband’s passing. To suddenly have the medals found after so long, was incredibly surprising.

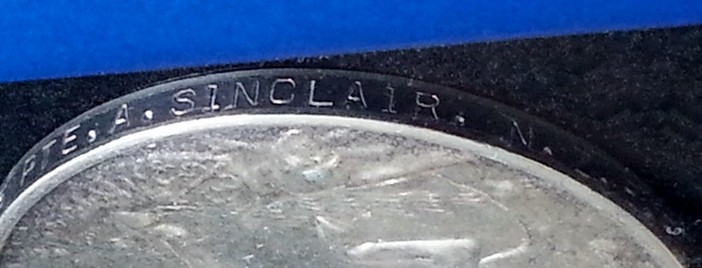

The medals were mounted in a small, glass fronted, blue painted wooden case accompanied with a photograph of Alexander Sinclair in uniform. Mike had never seen a photo of his great-uncle before and so had no reason to question its authenticity. Ruth, however, had visited her great-uncle Alec in his Dunedin home, and did not think the photo resembled him at all. On closer inspection of the case, attached to the back of the case were four pieces of paper, a letter detailing Alexander’s service history that had been reduced in size, cut into four, over-lapped and pasted to the fit the size of the case. The letter had been type-written on Ministry of Defence letterhead paper and so could be assumed to be authentic. Its authenticity was also verifiable as there was an addressee’s name and address hidden by one of the overlapped quarters. This implied the history was the result of a formal request to the NZ Secretary of Defence from a Mr P.R. Evans of Pialba, Queensland, a small coastal town in Hervey Bay. Neither Ruth nor Mike had any idea who this person was. Unfortunately the service history was undated as it would likely have been attached to a covering letter addressed to “Mr Evans”.

While corresponding with Ruth, she revealed to me more detail about how the medals had come into the family’s possession. Mike had a distant female relative who had lived in Christchurch until the earthquakes of 2011, after which she relocated to Brisbane. Mike said they had met briefly in 2009 while researching family history but since then Mike had not had any contact. Mike was surprised when he received an unexpected email from a relative in 2019 from Brisbane. She had written to tell Mike that a Returned Services (RSL) branch on the Sunshine Coast (north of Brisbane) had handed into them a frame containing three World War 1 medals named to Kiwi soldier, A. Sinclair, and believed they belonged to Ruth and Mike’s ancestor who had fought in France.

The medals had been left at a Lifeline charity shop around July/August 2019 and were subsequently passed to the RSL to hopefully return to the Sinclair family. By working through a genealogy group in Australia, an RSL member had identified Mike in NZ as being a relative of Alexander Sinclair and by following this up, had made the connection with Mike’s relative who moved to Brisbane and who also was remotely connected to the soldier. Since Ruth and Mike were much closer descendants than herself, she offered to give the medals to a visiting friend who was conveniently returning home to the Rangiora area, north of Christchurch. Excited at the prospect of having the apparently missing great-uncle’s medals back with the family, Mike agreed to meet the returning friend at their home where the medals were handed over.

Whose medals are these?

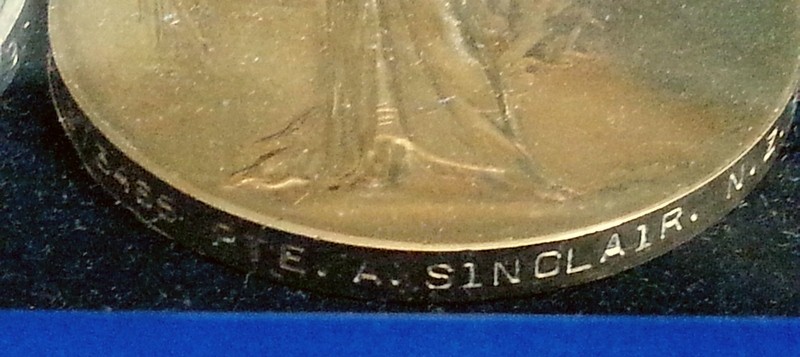

As Ruth had researched their great-uncle’s military history in some depth, she was fairly familiar with his service. In the months after receiving the medals, Ruth and Mike detected a serious anomaly in the service history on the back of the case – it was not that of their great-uncle Alexander Sinclair! Although correctly named to “PRIVATE ALEXANDER SINCLAIR”, the regimental number 6/3465 was not that of their great-uncle, and nor were the birth and date of death dates in accord with great-uncle Alec’s. Absent from the title was the soldier’s unit which in fact was in the small print half way down the printed history – very easily missed at first glance. The service history on the case was certainly that of an Alexander Sinclair who had been a member of the 1st Battalion, Canterbury Infantry Regiment. The problem though was that great-uncle Alec had been in the 1st Battalion, Otago Infantry Regiment! Had this fact been included in the title, the anomaly would likely have been detected much sooner. A check of the medals themselves proved that they had all been impressed with the number 6/3465 – not Alec’s regimental number which was 8/711 – this was an entirely different Alexander Sinclair! For the sharp eyed military enthusiasts among readers, you will be able to spot the other clear giveaway. The A. Sinclair in the photograph was not of the Otago Regiment. The soldier’s collar-dogs (badges on the collar) are clearly those of the 12th (Nelson) Infantry Regiment which could also be associated with Alexander Sinclair’s then place of work.

With this knowledge they considered researching a descendant family to return the medals to, provided that person could prove a rightful claim to them. On reflection, they felt there was always the possibility that, in attempting to do so, things could go off the rails and potentially see the medals either being sold, given away, going back into another charity shop, or worse – junked or abandoned! Ruth and Mike thought it might be better to give the medals to the National Army Museum or the Auckland War Memorial Museum. It was then that Ruth learned of Medals Reunited New Zealand, which is where I came into this story. The medals arrived with a request to return them to the family of 6/3465 Pte. Alexander Sinclair, Canterbury Infantry Regiment.

What’s in a number?

Regimental numbers that precede every service person’s official description are all important when it comes to correctly identifying a medal recipient, one of the main reasons the service number appears ahead of New Zealand service persons’ rank, name, formation, ship or service. An example of the difficulties associated with identifying medal recipients can be seen with those issued to officers of the Royal Navy, RN, Army and RAF. While the medals of the rank and file sailors, soldiers and airmen of this era were impressed with number, initials & surname, plus regiment, ship or service, officers’ medals carried only their rank, name and the arm of service to which they belonged! Imagine the difficulty in trying to identify a particular WW1 officer Smith, Jones, Brown with the same and/or similar initials but without a number to single out a particular individual – there were literally hundreds of these examples in the MEF and BEF. Thankfully post WW2 they no do thankfully. Whilst NZ and the UK impressed each medal with the service persons basic details, unfortunately this practice did not carry forward to WW2 campaign medals which were issued without names or any identifying mark. As a consequence, the finder or purchaser of WW2 medals has no ability to identify their original owner. The result is that many thousands of WW2 medals in circulation are practically worthless as they have no traceable history, ergo the service person’s personal story of service behind the medals. Each person has a unique story related to their service therefore the medal represents that person after death … no named person medal recipient = no medal history/story.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The error in thinking the medals named to ‘A. Sinclair’ belonged to Ruth and Mike’s ancestor was entirely understandable; for the inexperienced a single first name letter plus a surname might easily be assumed to belong to one’s own ancestor. Unfortunately, without additional verification, this is not enough to prove conclusively the identity of any World War 1 soldier or nurse. Mistaken identity, as in this case, reinforces just how critical a service number is to correctly identify the person. Try guessing how many A. Sinclair’s there were in British and Scottish regiments during WW1 or WW2? – hundreds! As I had no knowledge of 6/3465 PTE. A. SINCLAIR, I needed to first establish exactly who he was and who he was not, in order to conclusively prove who the medals in the case belonged to. It was also an important step in establishing which Sinclair family the soldier belonged to (given the large number of similarly named Sinclair’s in New Zealand at that time), and thus establish the correct lineage to follow in order to locate a living descendant. I also decided to ignore the reference to ‘Mr Evans’ mentioned on the history attached to the back of the case as that could confuse and potentially protract the research for not much gain. If I came across the name during my own search and he proved to be a near relative (if still alive?), I would cross that bridge then. As it turned out I did not make any connection with Mr Evans to the Sinclair families I researched – he may well have been a medal or militaria collector?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Identification & verification

The soldier I was seeking was a soldier who had been award the trio of WW1 medals. This was indicative of one who had been overseas in the designated war zone (France) before 30 December 1915, this being the pre-requisite to qualify for the award of the 1914/15 Star only. After that date, only two service medals were generally awarded – the British War Medal, 1914/18 and the Victory Medal, and very occasionally the British War Medal on its own.

Of the Sinclair’s named on the Cenotaph website, NINE soldiers had “Alexander” as their first name however only FIVE had served overseas, and three of these had no second or third given names. This can be a trap when looking for ancestors as many soldiers did not record their second or subsequent initials when enlisting as it was not considered an important detail and proof of identity was not required. Additionally, some soldiers enlisted under their preferred first name which was often actually their second or even third name, just to confuse the issue further. The three Sinclair soldiers I refer to were:

- Mosgiel – 24066 Emb 1916 – OIR, 13 Reinfs – Rtnd, awarded medal Pair Died 11 Feb 1949, Dunedin

- Dunedin – 8/711 Emb 1914 – OIB, Main Body – Rtnd, awarded medal Trio Died 09 Aug 1980, Dunedin

- Oamaru – 6/3465 Emb 1915 – CIB, 8 Reinfs – Rtnd, awarded medal Trio Died 14 Jan 1958, Wellington

Of the above three, I could rule out 24066 from Mosgiel as this soldier had only qualified for the pair of WW1 medals. Once I saw the AWMM profile page of 8/711 I could see immediately where the identity problem had arisen. Ruth had posted a note on this page some years previously, identifying herself as the “great niece” of 8/711 Private Alexander Sinclair who had served with the Otago Infantry Battalion. Great-uncle Alec Sinclair had married in 1894, had two brothers who served overseas – 2/201 Robert Christie Sinclair and 11160 Ernest Sinclair, and had died on 9 August 1980 in Dunedin.

The medals of 6/3465 on the other hand, had been awarded to Private Alex Sinclair who had married but not until after the war. While he too did not have any children and did have brothers however was the only male of his Sinclair family to have served in the NZEF. Alex Sinclair died in 1958, more than twenty years before Alec Sinclair. These facts alone proved (provisionally) that the medals in the case were definitely not those of Mike and Ruth’s great-uncle Alec Sinclair. A more comprehensive search would be needed to identify the correct Alexander Sinclair.

‘Hoots mon oche aye the noo .. Sinclair’

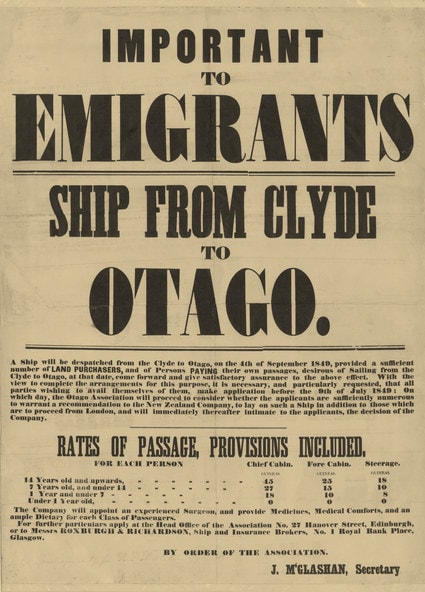

This case was an example of the difficulty in researching people with intergenerational, singular first names ….. stay with me…. Alexander Sinclair Jnr’s great-grandfather, Alexander Sinclair (Snr) was born in Leslie, Fifeshire, Scotland on 16 July 1834, to parents George SINCLAIR & Mary HERON. In 1851, 16 year old Alexander and the rest of his family were living in Wemyss, Fife where his father George had established himself as a Cabinet Maker while young Alexander was employed as Wemyss’ Weighbridge Keeper. Having also learned the skills of a carpenter, Alexander was 23 when the family – George, Mary, Alexander, Mary, Agnes and John – emigrated from Scotland to Port Chalmers aboard the ship George Canning in 1857, making good passage of 97 days, port to port. This was the first ship of numerous immigration ships that would follow under an immigration system introduced by the Provincial Council of New Zealand. One of the incentives to immigrate being offered at the time by the Government was a cash reward of 500 pounds for the discovery of a goldfield and 250 pounds for a coalfield.

When Annie died in 1894 at the age of 54, Alexander Snr. returned to a job he had first undertaken as a teenager at Wemyss – that of a Weigh-bridge Keeper, a position he held for the Oamaru Borough for the last 15 years of his life. Apart from a brief period as a school committee representative when living at Enfield, Alexander Sinclair Snr. was never associated with public affairs. It was while living with his son Alexander Jnr. in Ribble Street that Alexander Snr. (81) died on 18 May 1916 of senility and heart failure, while at the Victoria Home. He had been one of the few surviving pioneers of the province.

Born at Blueskin Bay Alexander SINCLAIR [Jnr] (1869-1946) began farming after the family moved to Enfield. The 1894 electoral rolls show him listed as a Butcher, this also being the same year he married Sussex born Laura MILLS (1871-1940) in Oamaru. Alexander Jnr. and Laura Sinclair had a family of four, the eldest being born in Dunedin and named … you guessed it – Alexander SINCLAIR (1894-1958). Gertrude Lenore SINCLAIR (1896-1986) and William SINCLAIR (1903-1992) were both born in Oamaru and the last child, John Duncan SINCLAIR (1904-1988) was born at Five Forks in rural Oamaru. Alexander Sinclair Jnr. died in 1946 at the age of 77, five years after his wife Laura passed away. Alexander and Laura’s eldest son was called “Alex” to avoid confusion with his father, the gentleman the remainder of this story is about.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Alexander “Alex” SINCLAIR (1894-1958)

A willing volunteer for overseas service, 6/3465 Private Alexander Sinclair was 20 years and 9 months of age when he was attested for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force on 24 August 1915 at Trentham Military Camp. After undergoing two months of basic training, Pte. Sinclair embarked onto HMNZT 35 Willochra with the 8th Reinforcements of the Canterbury Infantry Battalion (CIB). The Willochra departed on 13 November and headed for Egypt via Western Australia, arriving at Suez in Jan 1916. Here the 8th Reinforcements disembarked and entrained for the 74 kilometers journey north to the join the CIB at El Moascar Camp, situated outside the town of Ismailia on the west bank of the Suez Canal.

The NZ Division at this time was preparing for shipment to the Western Front, a new battleground that would be vastly different from Gallipoli. Those who fought at Gallipoli had been withdrawn in Dec 1915 to Egypt where the NZ and Australian Divisions were re-organised for the new battle front in France. The Divisions would be arriving in the midst of a northern winter and face a very different type of warfare than their Gallipoli experience. The NZ Division would also be part of a much larger international amalgam of Armies under British command. Fighting a trench war and gaining ground by the pursuit of the enemy in appalling weather conditions would be a feature of the many battles they would fight on the Western Front which would exact a toll no-one had fully comprehended.

To France

Following two months of intensive training (in desert conditions) at platoon, company and battalion level, the 8th Reinforcements were ready to embark for France, departing Alexandria for Marseilles in the south of France, on 6 April 1916.

Pte. Alex Sinclair’s Western Front experience got off to a bad start when shortly after his joining the 12th Company of the 1st Battalion, Canterbury Infantry Regiment in May 1916, he was taken sick to the 12th British Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), located in rear of the Armentieres front line at Hazebrouck. Here he was treated for an Inflated Perineum. In a man the perineum is the area between the scrotum and the anus. His condition worsened and he was moved to the 26th British General Hospital in Marseilles for further assessment. The diagnoses confirmed a Stricture of the Perenium, meaning the swelling of perenium was caused by the formation of an abscess indicating the presence of a serious infection. By mid-June Pte. Sinclair had been shipped back to England to the 2nd London General Hospital to await a vacancy in No.1 NZ General Hospital at Brockenhurst (or Mt Felix as it was sometimes called).

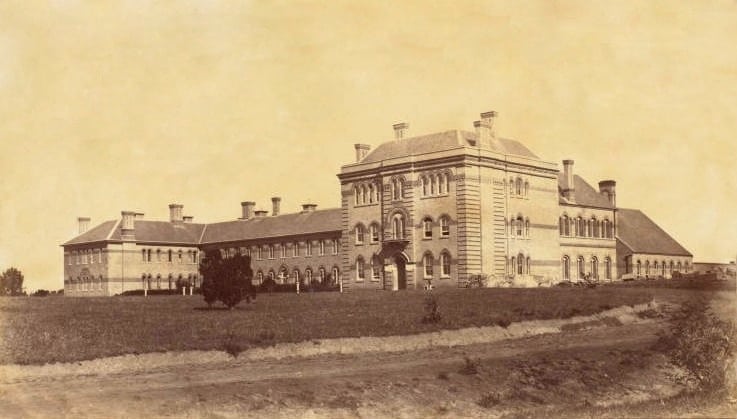

The NZ hospital at this time was still swamped with the worst casualties from Gallipoli, quite apart from those who had been shipped in since the move to France and Belgium. Eventually he was transferred and after several weeks of treatment 1 NZGH, the infection receded to the extent he was able to be transferred to the NZ Convalescent Hospital at Hornchurch on 8 July 1916 – known to soldiers as ‘Grey Towers’. After two months of convalescence, Pte. Sinclair was deemed fit enough to return to France. He was first returned to the NZ Base Depot at Sling Camp to await a ship transport. On 26 September he crossed the Channel to the NZ Infantry & General Base Depot camp at Etaples before being sent forward to re-join his battalion.

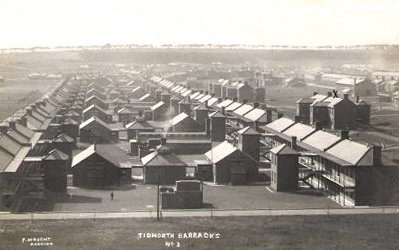

Pte. Sinclair had indeed been fortunate being hospitalised when he was as he had avoided one of two ghastly battles that resulted in a huge loss of life for the NZ Division – the Battle of Messines, 7-14 June 1916. For the next twelve months Alex kept his head low and survived the advances the Canterbury Regiment made through Polygon Wood and various other actions that were the beginning of the campaign referred to as the Battle of the Somme. Two days prior to an action during the 3rd Battle of Ypres in Belgium that would be infamously remembered as ‘New Zealand’s darkest day’ – Passchendaele – Pte. Sinclair’s regiment was advancing on the village of Esnes with the remainder of the New Zealand Division on 10 October when he was cut down by severe gun-shot wound to his right thigh. This resulted in his returned to England once more and a lengthy period of recovery that lasted until mid-1918 before he was deemed to be battle fit for return to the front. Before he returned to France however, Alex was required to undertake an NCO training course at the Jellalabad Barracks in Tidworth, a precursor to his promotion when he returned to the field in France.

Pte. Sinclair arrived back at his unit on 24 October 1918, just in time to take part in the last action the NZ Division would fight in the war. One of the key objectives for the Division during the final days of the ‘Advance to Victory’ phase involved the capture of the medieval walled town of Le Quesnoy. This was successfully executed at some cost to the New Zealanders but without the loss of life of a single French citizen’s life, before the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918, thereby officially bringing an end to hostilities.

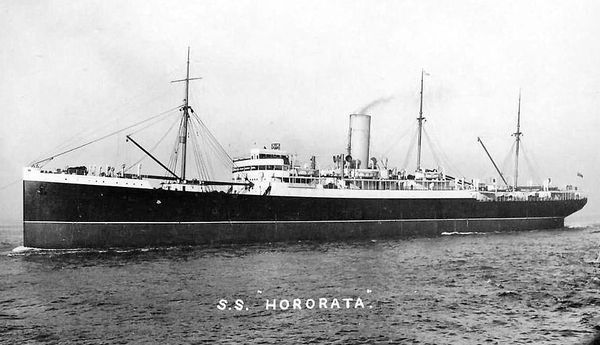

Pte. Alex Sinclair’s return to NZ however was still some months away as priority was given to return the longest serving soldiers (the category he fell into), but British soldiers first! The plans for troop repatriation were further thwarted due to a shipping strike which reduced the availability of troop transport vessels and caused long delays for the waiting troops desperate to get home. Finally, having completed his de-mobilisation at NZ Discharge Depot at Torquay, Alex returned to Wellington aboard the HMNZT 221 Hororata which left London on 1st of February, 1919 with almost 1600 troops from the Main Body, and arrived in Wellington on 15 March, 1919. Four weeks later while at home on leave, Alex’s commitment of service in the NZEF officially expired and he was discharged with effect from 13 April, 1919.

Medals: 1914/15 Star, British War Medal, 1914/18, Victory Medal + Silver War Badge (SWB) for wounds sustained.

Service Overseas: 3 years 123 days

Total NZEF Service: 3 years 233 days

A career in Mental Health

After the war Alex Sinclair returned to Nelson and his former position at the Nelson Asylum, re-named in 1922 to the Nelson Psychiatric Hospital. In 1924 Alex married Ruby Christina BURNS (1900-1978), one of four Wellington born daughters of Scotsman John BURNS and his wife Elizabeth Sylvia RICHARDS. Shortly after their marriage Alex was took up an appointment in Auckland. He and Ruby moved into the staff quarters of the Auckland Lunatic Asylum in Carrington Road, Point Chevalier. The Asylum was also later re-named variously to the Avondale Lunatic Asylum and Avondale Hospital. From 1959 several more name changes included the Auckland Mental Health Hospital, Oakley Hospital and Carrington Psychiatric Hospital.

Alex and Ruby returned to Wellington in 1935, temporarily to 80 Anne St in Wadestown for a couple of years before moving to their ‘forever’ home at 80 Pitt Street in Karori. While in Wellington, Alex continued to advance up the ranks of the Health Department’s Mental Hospitals administration, eventually being appointed the NZ Administrator for Government Mental Institutions. Alex held this appointment until his untimely death on 14 January 1958 at the age of 64. His remains were buried in a soldier’s grave in the Karori Cemetery. While no children eventuated from Alex and Ruby’s union, Ruby remained a widow living alone in their Pitt Street home for the next twenty years until she too passed away at home on 23 July 1978. Ruby was 78, her remains were buried at the Makara Cemetery on Wellington’s west coast.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Australia calling …

Sinclair is just as prolific a name in Otago as it was at the turn of last century, with generations invariably using singular first names, these being duplicated in each successive generation. This made the assembly of this particular Sinclair family lineage no mean feat and the source of much consternation (and confusion) as the following will show. Rural families made the task that much harder save for the fact that by mid-century, farms had been well established and movement was minimal, largely limited to the traditional areas of origin or settlement. Having done my best to gather the essentials of Alec Sinclair’s family, I posted the medals on our Medals ~ LOST+FOUND page of the MRNZ website, as is done for all medals we receive. This allows the public to peruse the pages which has on occasions saved a lot of research time when someone recognises an ancestor or a name and can connect us with a descendant. It was clear this was not going to be a quick return so at that point I set this case aside in order to complete other pressing cases.

As luck would have it, I needed to go no further with my research after receiving an unsolicited phone call in July this year (2023) from Colin in Western Australia. Colin said he had seen the posting of the Sinclair medals on the MRNZ website and had called to advise us that he was a great-nephew of Alex Sinclair’s younger brother William (1903-1992) and Maud Matilda Sinclair (nee HACQUOIL). Colin undertook to try and make contact with his cousin Barrie, the son of William and Maud’s first born son …. stay with me readers ….. William “Bill” Sinclair (b1926) and his wife Annie Joyce, nee WILSON. Bill and Joyce had been farmers at Weston, Oamaru where they had raised their family. Colin called me back a few weeks later with a phone number after making contact with Barrie.

After explaining to Barrie the purpose of my search for Alex Sinclair’s descendants, subject to his providing proof of ancestry and his connection to Alex Sinclair’s family, I told him he was the person most likely to receive Alex’s medals. Barrie then took my breath away somewhat when he announced that his father Bill Sinclair was alive and well! With no traceable contact on-line, I assumed (wrongly) that Bill had probably passed on and concentrated on the younger Sinclair generations. Being the oldest living direct descendant of Alex, Bill Sinclair was the person most entitled to Alex’s medals ahead of son Barrie. Barrie said his father was currently in an Oamaru rest home and while somewhat fragile, was still relatively hale and hearty and about to celebrate his 95th birthday in August. Barrie said later when he told his Dad about the medals, Bill was excited to hear the news as he remembered Alex quite well when growing up as a lad. They had worked together on the farm and Alex had rewarded Bill with half a crown (about 50 cents, a substantial sum for a boy back in the day), something Bill had always remembered fondly. With Alex’s medals now in Bill’s hands, it was a pleasure to receive these photographs from Barrie of the occasion – him and his Dad with the medals returned to the Sinclair family fold.

Ruth and Mike initiated this case and it would have been just as easy for them to send the medals back to the RSL acknowledging the medals were not of their ancestor. By taking the step to make contact with us, they have been instrumental in the medals going to the correct descendant family who otherwise would probably never have known where they had ended up.

My thanks to an eagle-eyed Colin in Western Australia for spotting the medals on our website and making the connection, a short circuit that was most welcome and ensured a speedy return of Alex Sinclair’s medals to his descendant family.

The reunited medal tally is now 498.