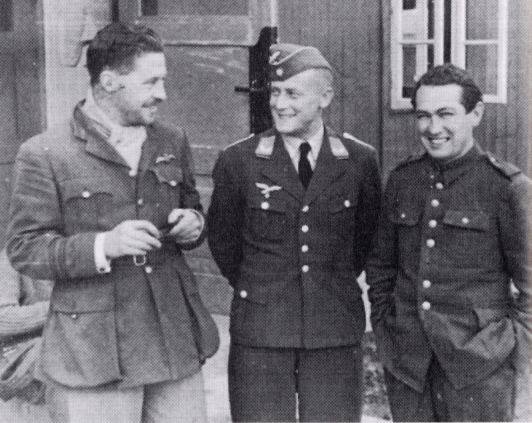

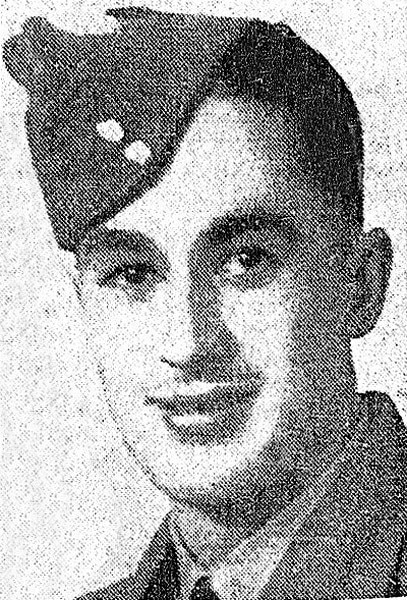

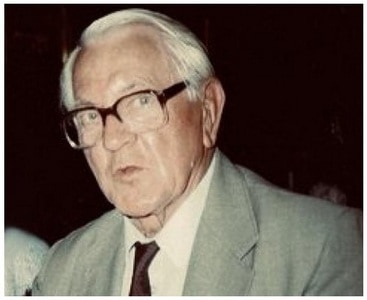

Eighteen months ago MRNZ reunited the war medals of a World War 2 bomber pilot from Timaru with a Dunedin descendant of his family (see MRNZ Fb post November 13, 2021). Writing up the story of the late Flight Lieutenant (Pilot) Herbert Douglas Newman (mid), has taken much longer than I anticipated to produce due to the number of conflicting accounts by those who have written of an event most people have heard of, “The Great Escape”. Herb Newman was in the Stalag Luft III tunnel while the escape was in progress, himself just minutes from being the last man to exit. Had he made his escape, Herb could very well have been one of the 50 escapees who were executed on Hitler’s orders!

The fact of Herb Newman being a POW in Germany during World War 2 was never in doubt, and was easily proven by his descendant Newman families. To establish if there was more to his story family so I set out to track his path during captivity and to uncover the circumstances of his escape(s) and what part he had played. I am confident my research has achieved 95% accuracy, at the risk of spending the rest of my life searching for five percent I continue to remain unsure of.

Overview

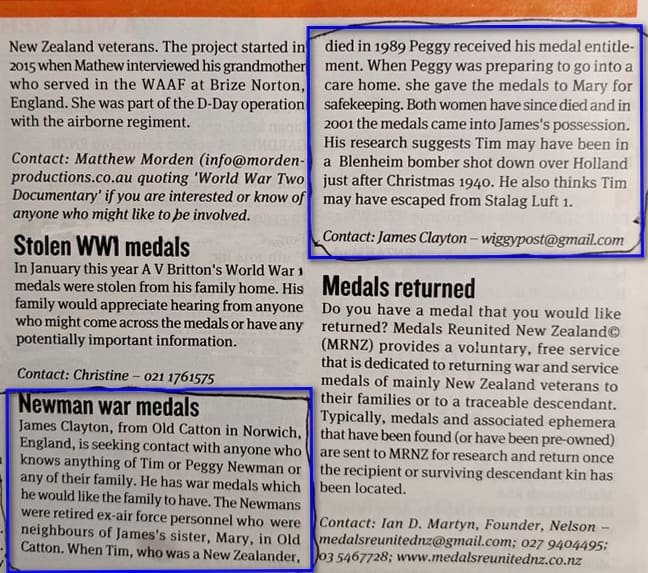

This story is the conclusion of what began for me with an advertisement in the now defunct RSA Review newspaper. The RSA Review was a long standing publication published quarterly for the benefit of military veterans and their families. In 2020 the Review ‘went to the wall’ with its Summer Edition (Oct) being the last. Despite the loss of this newsworthy institution, the RSA Review unwittingly facilitated one final act of commemoration and remembrance for the Hanning family of Dunedin.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

James Clayton is a retired educator who lives in Woodland Drive, Old Catton in Norfolk, England. In May 2020, James sent an advertisement to the RSA Review (outlined in blue) which appeared in the Winter (July) edition.

When I received my copy of the Review, flicking through the pages I saw an advertisement in the “Lost Trails” column from James Clayton with an email address included. I circled it out of interest but being up to my ears in other medal research projects, I didn’t give the ad any more thought. Fast forward to June of 2021 – I happened to pick up that same copy of the Review (nothing military moves far from my bunker) and James’s advert again caught my eye. On the spur of the moment I dashed off an email to him more out of curiosity, to enquire whether he had had any responses to his advertisement.

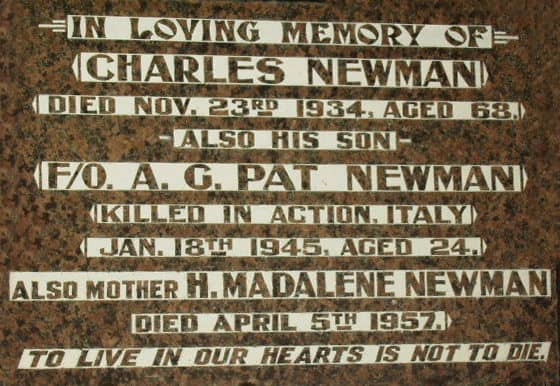

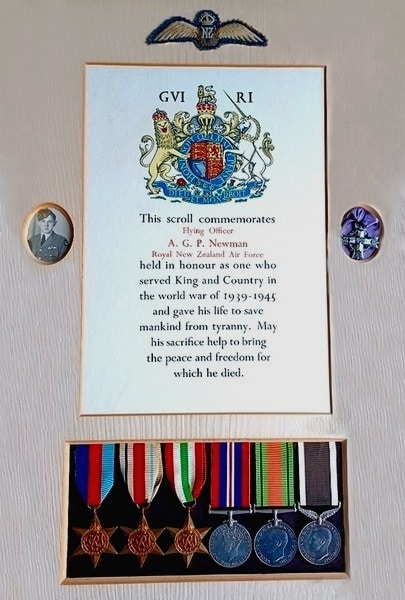

While waiting for his reply, I took a brief look at my reference material to find out who exactly Herb Newman was. Born and bred in Timaru, he had joined the RNZAF in 1939 as a pilot, trained in Canada and been a bomber pilot in the RAF. As James rightly stated in his advert, “Tim” had crashed in Holland (not in a Blenheim as he had thought but a Vickers Wellington) and had subsequently escaped from a POW camp, Stalag Luft I. More importantly however, I discovered Newman had also been interned in Stalag Luft III, the camp made famous by the ‘Wooden Horse’ and ‘Great Escape’ stories and movies of the same name. My interest escalated tenfold! As an aside, when looking for Tim’s grave, the family plot in the Timaru cemetery also carried a plaque to Tim’s younger brother Andrew George Patterson Newman who had also joined the RNZAF/RAF but sadly was killed on air operations in 1945.

James emailed response to me indicated he had heard nothing except for a comment from NZ aviation historian who had proffered some information related to Tim’s aircraft prang in Holland. I explained to James what it was I did and asked him if he minded if I took up inquiry to see if I could locate a Newman descendant. James welcomed the assistance, but before I began the search, there were a few burning questions I had for James. First, what did he intend for the medals; second, how did he come to be in possession of Newman’s medals, and last, why did James refer to Herb as “Tim” as it didn’t feature in any of his birth names?

Background

James explained to me he had known “Tim/Herb”? from Old Catton and that he had had the medals since 1989. As “Tim/Herb” had no family or relatives in the UK, and he (James) not getting any younger (then approaching his 85th birthday), he felt the medals should rightly be returned to New Zealand preferably to a relative and so had placed the advert as his last ditch attempt to hopefully have that happen. How did James come to be in possession of the medals?

James Clayton takes up the story ….

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

NEUMANN ~ NEWMAN

Fredrich Wilhelm NEUMANN (1837-1927) was German born, from Arnau (now Rodniki, 150km NE of Gadansk), Ostpreussen (East Prussia) in the former Kingdom of Prussia, and the paternal grandfather of Herbert Douglas NEWMAN. Herb’s grandmother was Eliza SIZEMORE (1838-1913), born in Waikouaiti, Southland, the daughter of Horse-rider, Sealer, Cooper and convict Richard SIZEMORE (1802-1861). Richard, a native of Bristol, Gloucestershire, was 22 when he was convicted for Theft at the Liberty of Tiverton Quarter Session in Devon on 24 October 1814. Sentenced to seven years Transportation to the Sydney penal colony, Richard arrived in Sydney aboard the General Grant in 1818. In August 1825 he was finally granted a Ticket of Freedom. By 1838 he was living in Bluff and was married the same year to Waniwani “Winnie” NGAPUHI (1818-1842) of Kororareka (Russell) in the Bay of Islands. Prior to the World War 1, Frederick Neumann anglicised his surname to “Newman”– for obvious reasons. He spent the latter part of his working life as a newspaper Compositor.

Herb Newman’s father Charles William NEWMAN (1865-1944) was born at Waikouaiti, North Otago. A newspaper Compositor (type-setter) living in Aramaho, Wanganui, Charles had followed his father Wilhelm into the newspaper printing business. In 1900 at 34 years of age he enlisted with the 4th NZ (Rough Riders) Contingent, NZ Mounted Rifles to fight in the South African Boer War (1899-1902). On his return (and recovery from Malaria) he was commissioned in the rank of Lieutenant and joined the 9th Contingent, NZMR. In 1907 Charles had moved to a Dunedin paper where he married Herb’s mother, Harriet Madeline Sizemore BAIN (1889-1957) of Dunedin. The Newman’s moved to Temuka and later on to Timaru, Charles still working as a compositor (later known as a lino-type operator) at the Timaru Herald.

Herb Newman

Herbert Douglas Newman was born at Temuka on 06 July 1918, the fifth of seven children – Elizabeth Ethel [Newman] BROWN (1909-1982), Charles Joseph ‘Joe’ NEWMAN (1911-1972), William Matthew ‘Bill’ NEWMAN (1914-2001), Gertrude Rosetta ‘Gert’ [Newman] BROWN (1915-1999), ‘Herb’ NEWMAN, Andrew George Patterson ‘Pat’ NEWMAN (1920-1944), and Doreen Huirapa [Newman] CHING (1923-2008).

Growing up in Timaru, Herb attended the Timaru Main School from 1923. He was an average scholar however did make it into the local newspaper on at least one occasion when his named featured in the Standard 5 Honours list of July 1931 – Herb was the recipient of a MERIT award for attendance! He went on to Timaru High School and while the results of his studies did not bode well for a career in brain surgery or rocket science, a solid pass in the core subjects ensure he left school equipped well enough to join the RNZAF when war threatened in Europe. After leaving school, he had various odd-jobs such as selling newspapers, labouring etc until the spectre of war intervened.

For God and Empire

For the second time in twenty years, war clouds gathered over Europe and New Zealanders collectively held their breath in anticipation of another national commitment of the nation’s finest young men for war service. While national registration had not yet been initiated, those who pre-emptively volunteered for war service before June 1940, were permitted to choose in which of the three armed services they preferred to serve – NZ Army, RNZAF or Royal Navy (UK). Herb wanted to fly and so had chosen the RNZAF.

Those who passed the enlistment preliminaries for the RNZAF and a pilot’s basic flying tests, went on to advanced pilot training in Canada or the UK to complete an operational pilot’s qualification, or an aircrew appointment in air gunnery, wireless operation or observation (navigation). Once qualified each man would be allocated to an RAF squadron in one of three operational commands – Fighter, Bomber or Coastal Command. Initially Pilots and Observers were officers or warrant officers while seniors NCOs (the minimum aircrew rank was Sergeant) mostly made up the ranks of the remaining crew appointments. This tended to change to suit a need as the war ground on and casualties soared.

Per Ardua ad Astra (‘through struggle to the stars’)

Military service for the Newman siblings had been inspired by their father’s service in the Boer War. As World War 2 loomed and preferences were being selected among the eligible as to which arm of service they would join, Herb’s two elder brothers, Joe and Bill both opted for the Army. Younger brother Pat having been a Territorial soldier in South Canterbury, initially enlisted with the Army however changed tack and applied for pilot training, following his brother Herb into the RNZAF.

Herb Newman’s application to join the RNZAF as a pilot trainee was successful. On 13 June 1939 Herb and his fellow aspirants were officially gazetted for pilot training in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and short-service commissions in the RAF. The NZ Gazette and the Wellington Evening Post published the following:

“Royal Air Force Candidates training in the Dominion.”

The Minister of Defence (the Hon. F. Jones) announced today that the following twenty candidates had been selected for training in New Zealand for appointment to short-service commissions in the Royal Air Force. Four candidates will be reporting to each of the Auckland, Wellington, Wanganui, Canterbury, and Otago Aero Clubs on July 3 in order to commence their flying training:– H. D. Newman, Timaru, etc etc…

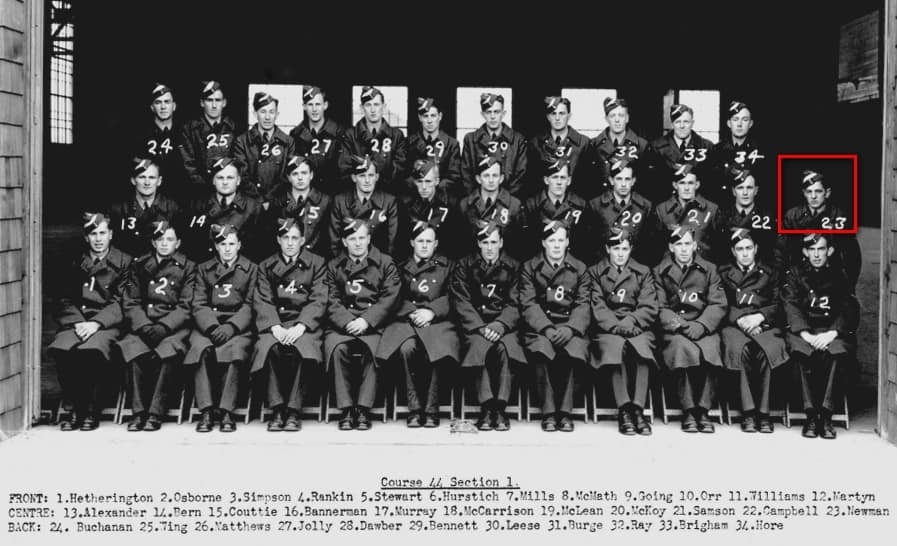

9 Pilot’s Course ~ No.1 Service Flying Training School, RNZAF Station Wigram.

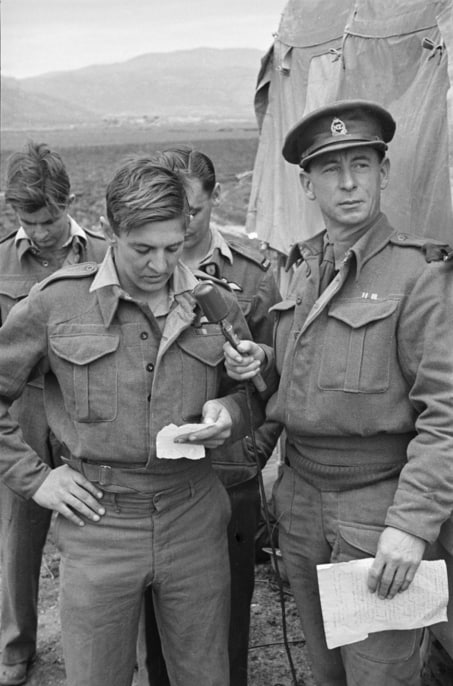

The course was split into two flights for training – November 1939.

Back L-R: Acting Pilot Officers CW Miller, GN Fitzwater, A Bridson

Front L-R: Acting Pilot Officers WH Hodgson, HD Newman, CK Saxelby, JL Bickerdike.

On 12 September 1939, the twenty aspiring pilots were appointed to the Reserve of Air Force Officers (RAFO) and twelve days later, were officially gazetted with temporary commissions in the rank of Acting Pilot Officer (General Duties) in order to attend No.9 Pilot’s Course at RNZAF Station Wigram. Acting rank for the duration of flying training allowed the trainees access to the Officers’ Mess and its facilities which was all part of their overall assessment of being suitable (or not) to hold a commission. The ability to fly and gentlemanly behaviour were assessed in equal measure – fail either and you were out!

The first job this group of twenty pilots (those who graduated) would be required for was to fly ten Vickers Wellington heavy bombers ** back to New Zealand. These had been gifted to the RNZAF by the Royal Air Force following the constitution of the RNZAF as a separate service on 1st April 1937 (previously it was part of the Army).

Note: ** The New Zealand Government had ordered 30 Vickers Wellington Mk1C bombers in 1938. RNZAF aircrew were sent to England to train on the new aircraft based at RAF Marham. These crews were to fly the aircraft to New Zealand in batches of six. RAF official records name this group of airman as “The New Zealand Squadron”.

When Britain declared war on Germany, the New Zealand Government made the airman and the aircraft available to the RAF to help with the war effort. As the young pilots who had been tasked to fly the aircraft back to NZ had completed their ‘wings’ training, these were offered to the RAF on a Short Service Commission (SSC) basis for the duration of the war.

A decision by the British Air Ministry to give them this NZ squadron the defunct No. 75 Squadron number-plate on 4 April 1940, meant that the nucleus of The New Zealand Squadron personnel remained together as an operational unit of the RAF. This was the first Commonwealth squadron to be so created in the Second World War.

RNZAF Stations Rongotai & Wigram

Before the A/P/O’s u/t (under training) got anywhere near an aircraft, they would first had to learn some basics of military routine and how to be an airman. They duly reported to the Ground Training School at RNZAF Station Rongotai (other side of the runway, opposite the Wellington Airport terminal building) where they would spend 8-10 weeks being tutored by Drill & Weapon Training Instructors (NCOs) in the basics of military life – marching and drill (square bashing), how to salute, recognise ranks, badges, flags and pennants, become acquainted with the customs of the service, learn how to maintain and wear their uniform, domestic duties such as cleaning barracks (and themselves), rifle and pistol training etc.

Once their air force indoctrination was complete, the A/P/O’s u/t were posted to No.1 Flying Training Squadron (1FTS) at Wigram to being flying training assessments. Those who showed the necessary aptitude were then place on a pilot’s course with the aim of getting them to the stage of flying solo which would earn them their Flying Badge, or ‘Wings’ as they are commonly referred to. Those who did not met the piloting criteria, or were removed from the pilot’s course for any reason, were re-cycled as potential air bombers/aimers, air gunners or wireless operators. Those APOs who failed to gain their Wings were given the option to be an Air Observer (title changed to Navigator in 1944), or an NCO air gunner, bomb aimer/air bomber, or wireless operator.

Graduation

NZ2508 A/P/O u/t Herbert Douglas Newman had spent 12 weeks of intensive flying training and testing by day and by night, at Wigram. No longer ‘under training’, A/P/O Newman and 13 of his fellow pilot trainees on No 9 Pilot’s Course received their Flying Badge (‘Wings’) on Saturday, 10 February 1940 during a graduation parade held at RNZAF Station Wigram.

Fourteen acting pilot officers whose training on the Ninth course at the Training School

at has been completed were passed out on Saturday. Twelve of them who are going

overseas will leave later this month to join the Royal Air Force.

Back L-R: Acting Pilot Officers H.G. Ballantyne, A. Bridson, C.K. Saxelby, J.L. Bickerdike, C.W Miller, E. Orgias.

Front L-R: W.H. Hodgson, N.C. Petit, P.K. Sigley, W.O.G. Krogh, H.D. Newman, G.N. Fitzwater, P. Robinson.

Acting Pilot Officer W.D. Finlayson was absent from the group. Acting pilot Officers Bridson and

Krogh are to be retained for service in the Royal New Zealand Air Force in the Dominion.

Feb 13, 1940: Photo: Press Historic Collection ~ Air Force, pilots WWII – Green & Hahn.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Herb Newman readied himself for the five week voyage to England. On 23 Feb 1940, twelve SSC Acting Pilot Officers** embarked onto the SS Rimutaka and departed Wellington for Southampton. Not only was it a memorable day for the young pilots but also for 100,000 Aucklanders who had turned out for a street parade in the center of Auckland to welcome home the crew of HMS Achilles who had recently survived the Battle of the River Plate fought in December 1939.

Note: ** Of the 12 pilots who graduated from No.9 Pilot’s Course and served overseas with the RAF, only two survived the war – Herb Newman and Clive King Saxelby, both of who became German Prisoners of War (POWs). The remaining course members were either killed on air operations (KAO) or in air accidents (KAA) while training.

NZ sent a total of 134 RNZAF trained pilots to the RAF on SSCs. Of these, 71 were killed/died (53%) and 63 survived.

Operational training in the RAF

The young Kiwi pilots arrived at Southampton on 13 April 1940 where they were entrained for No.1 (RAF) Depot at Uxbridge (the Recruit Receiving Centre). At this time the twelve airmen relinquished their RNZAF commissions and were formally granted a RAF Short Service Commission (SSC) with the rank of Temporary Pilot Officer (T/P/O).

Posted to No.1 Flying Practice Unit (1 FPU) at Meir, Staffordshire, the pilots commenced their advanced flying training on the Hawker Hind, a bi-plane that was used as a light bomber, to practice the fundamental skills of aerial bombing. On 12 May, T/P/O Newman was posted to No.12 Operational Training Unit (12 OTU) at RAF Benson near Wallingford in South Oxfordshire for a further 12 weeks of aerial bombing training in the much larger Fairey Battle, a light bomber mono-plane.

Having mastered the daytime bombing skills, as the majority of operations were conducted under cover of darkness T/P/O Newman was sent to RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire on 29 June to undertake night bombing training on one of the three light bomber types in the RAF inventory – the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. This was a twin engine light bomber not dissimilar in appearance to the Handley Page Hampden and the Avro Lancaster heavy bombers. In late July, a posting to No.22 Operational Training Unit (22 OTU) at Wellesbourne Mountford in Warwickshire gave T/P/O Newman his first day and night flying experience with a medium bomber, the twin engine, long range Vickers Wellington Mk 1a. After six weeks of flying and assimilating the aircraft systems and roles of the crew, T/P/O Newman was considered ready for his first operational sortie and posted to RAF Stradishall, near Haverhill in Suffolk in preparation for targets in France and Germany.

At this point Herb shed the “Temporary” prefix from his rank and was confirmed in the rank of Pilot Officer. It was also around this time that Herb Newman gained a new ‘name’. As the story goes, Herb never let an opportunity pass (particularly in the Officers Mess bar) to extoll the virtues of living in New Zealand, with particularly emphasis on his home town of Timaru. Because of his apparent fixation with talking about Timaru, Herb’s colleagues re-named him “Tim”, the name he was forever after known by in the RAF.

As he was now ready to begin operational flying, P/O Tim Newman was assigned to Bomber Command’s No.3 Group in Sep 1940. Tim joined a squadron that was crewed predominantly with New Zealand pilots and aircrewmen, topped up with RAF and RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) crewmen as needed. No.75 (NZ) Squadron** was based at RAF Feltwell in Norfolk flying the Vickers Wellington Mk 1a and Mk 1c heavy bombers on night bombing raids. Newman initially occupied the right hand seat as 2nd Pilot during his first few operations in order to gain experience in live night bombing.

Seven squadrons had a New Zealand identity in the RAF and were manned largely by New Zealanders on loan to the RAF. The first was Bomber Command’s 75 (NZ) Squadron and then 487 Sqn, while three more were Fighter Command squadrons (485, 486, 488) and the last two in Coastal Command squadrons (489 and 490).

The ‘Whimpy’

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engine, long-range, medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. The twin-engine Vickers Wellington continued to serve with distinction throughout World War II, despite eventually being superseded in its primary role by the much larger, heavy bombers such as the Avro Lancaster and the Vickers Warwick.

The Vickers Wellington B Mk X nicknamed the “Wellie” or “Whimpy” was to bear the brunt of Bomber Command’s offensive against Germany, making up some 60% of the aircraft in the first 1,000 bomber raid launched on 30 May 1942. The Wellington also served with distinction during marine reconnaissance and anti-submarine duties with both Coastal and Overseas Commands throughout the war. The robust nature of its revolutionary construction paid real dividends in terms of both aircraft and lives saved throughout the night bombing campaigns. One Vickers Wellington (LN514) became the subject of a Ministry of Aviation propaganda newsreel in October 1943, when it was constructed in just 23 hours 50 minutes by workers at the Broughton Factory near Chester, which now produces wings for Airbus. A total of 11,461 Vickers Wellingtons were built at Weybridge (Brooklands), Chester (Broughton) and Blackpool (Fylde).

The Wellington’s crew of six consisted of a Pilot (in command), Air Observer/Navigator who also doubled as the 2nd Pilot in an emergency, a Bomb Aimer [aka Air Bomber] / Front (nose) Air Gunner for the 2-gun front turret, a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner to maintain communications and man the port or starboard waist guns as required, and an Air Gunner for the Rear (tail) 2-gun turret. The Wellington could carry a bomb load up to 4,000lb, had a range 1,885 miles at 180 mph with 1,500lb bomb load, and a maximum speed 255 mph (410 kms/hr).

Night bombing operations

Between 08 September and 29 December 1940, P/O Tim Newman flew a total of 14 Operations with 75 (NZ) Squadron, nine of these as the 2nd Pilot, and five as 1st Pilot/Pilot in Command. Most of these sorties consisted of between an eight and ten ‘ship’ formation of Wellingtons for each mission. Tim’s first operational sortie as 2nd Pilot was Raid No CB.141, a nine ‘ship’ formation of Wellingtons whose targets were the railway marshalling yards and docks at the port town of Le Havre, France. Pilot in Command of Wellington Mk.1c L7797 AA-F for the operation was Pilot Officer John Edward Stewart MORTON, RAF. Aside from Tim, the remainder of the crew on board were P/O Alexander ANDERSON, RNZAF (Observer), Sgt. H. G. CAMPBELL, RAFVR (Wireless Operator), Sgt. R. BROWN, RAFVR (Bomb Aimer-Front/Nose Gunner) and P/O Norman Dudley Greenaway, RNZAF (Rear/Tail Gunner). Operational Reports produced from this mission showed some of the docks at Le Harve and a number of barges were hit with the aircraft’s mixed load of high explosive and incendiary bombs, while a number of targets were missed. The aircraft returned undamaged.

For the next eight sorties, the raids generally were made up of anything between eight and ten crew mix remained the same and the targets varied between Le Havre, Hamburg, Berlin, Osnabruck, Hamm, Munster, various aerodromes, railway marshalling yards and ship yards. Engagement with enemy aircraft was minimal with only one shot down by the rear gunner however flak encounters throughout these nine sorties ranged from medium to heavy.

P/O Newman’s first bombing sortie as Pilot in Command (Operation #14) was on the night of 6 Dec 1940. His crew consisted of four New Zealanders and two RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) Sergeants. The crew remained unaltered for the remainder of Newman’s subsequent sorties:

- 1st Pilot/PIC – P/O Herbert Douglas ‘Tim’ NEWMAN, RNZAF (Timaru)

- 2nd Pilot/Observer – P/O Robert Garth ‘Bob’ STARK, RNZAF (Greymouth)

- WOp/AG – Sgt John Middleton ‘Jack’ GARRETT, RNZAF (Auckland)

- AG – Sgt David Garrick Branscombe ‘Dave’ PROTHEROE, RNZAF (Lifuka, Tonga)

- AG – Sgt Sidney Lawrence ‘Sid’ SPITTLE, RAFVR (Croydon, London)

- AG – Sgt Manville Charles ‘Charlie’ FENN, RAFVR (Manston, Kent)

75 (NZ) Squadron – Operation #14

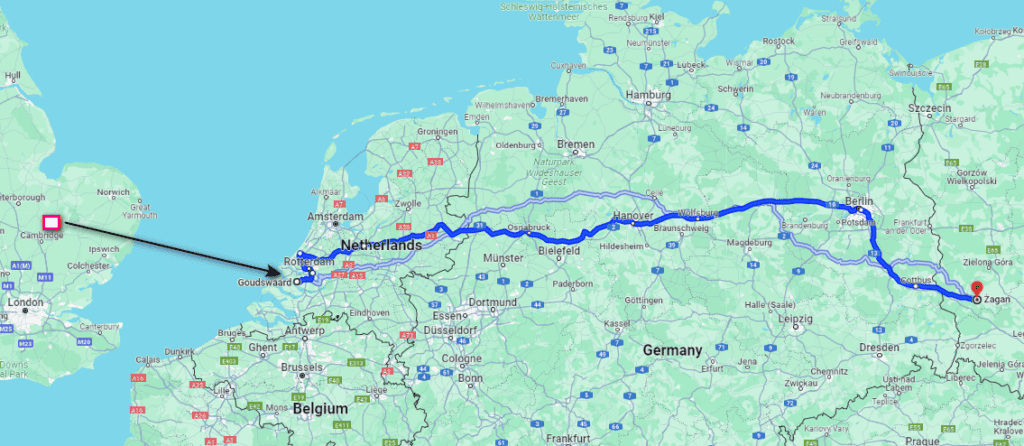

On the night of 29/30 December 1940 P/O Newman was PIC of 75 (NZ) Sqn aircraft, Wellington-1c R3211–AA-J which left RAF Mildenhall (just north of Cambridge) at 0013 hours to conduct a bombing mission on the marshalling yards at Hamm, Germany.

Flying over Holland on the return sortie, the aircraft running low on fuel encountered unexpectedly strong headwinds and as a result crash landed at Goudswaard (Zuid Holland), near Rotterdam. In commenting on the crash during an interview in 1990, Tim Newman said “because it was so dark, I had anticipated ditching in the sea and prepared the crew and aircraft accordingly.” Imagine his surprise when he crash landed on mudflats, the tide being out at the time. The crew extricated themselves from the aircraft despite their injuries, with the exception of Jack Garrett who was badly hurt and needed to be carried. The crew found themselves in knee-deep mud and struggled to drag themselves and their injured comrade ashore.

Once ashore they sought a hiding place to assess their circumstances however, a German patrol that had seen the aircraft go down, were on the scene within minutes to capture the downed airmen. While the crew had survived the crash, most had sustained injuries of one sort or another, WOp/AG Sgt. Jack Garrett had fared the worst having broken his hip and was severely concussed by the impact. Jack was removed by the Germans to nearby Rotterdam hospital. Much to the bemusement of the German doctor who examined him, when presented to the doctor, Garrett was found to be already wrapped in plaster! Jack had broken several ribs in a rugby match not long before take-off.

The remainder of the crew were transported by bus to Amsterdam and then on to Cologne where they were interned in the local jail overnight, 31 Dec 1940 – some New Year’s Eve! Next day the crew was entrained East through the Ruhr Valley 968 kilometres to the first of several POW camps in which they would be imprisoned. Oberursel is a scenic town about 21 kilometers north-west of Frankfurt, today the 13th largest town in Hesse. In 1940 it was the location of the Dulag Luft, a POW camp specifically for captured airman and run by the German Luftwaffe.

With Jack installed in Rotterdam Hospital (he would eventually be transferred to the hospital at Hohemark, Oberusal and re-join the crew), little did Tim and the crew of Wellington-1c R3211–AA-J realise they would spend the next four and a half years “in the bag” as Kriegies.

Note: To be put “in the bag” is military jargon for the incarceration of Allied Prisoners of War.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

German (Nazi) prison camps

The German word for Prisoner of War (POW) is kriegsgefangenen which inevitably became shortened to ‘kriegie’. Airmen POWs were generally interned in a Luftwaffe run Stalag, a prison camp either temporary or permanent for air force personnel only, despite there being a few navy (Fleet Air Arm) and Army who had been caught up is the roundup of prisoners when detected. Stalag is the contraction of Stammlager, itself short for Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschaftsstammlager whose literal translation is War-prisoner (i.e. POW) Enlisted – Main Camp. Therefore technically ‘Stalag’ simply means main camp. Luft is the German word for Air, and Luftwaffer for Airforce. Oflag is a contraction of Offiziers Lager which was a camp for officers, literally Officers Camp.

Almost all air force personnel captured in German occupied Europe passed through the German Luftwaffer’s POW camp system which was composed of three initial installations: an Interrogation Centre at Oberusal; the Hospital at Hohemark; and a Transit Camp established in Wetzlar. Thereafter they would be assigned to a permanent POW camp.

Initially the officers and other ranks had been lumped together in the same compound. This however produced a myriad of headaches for the Germans through the POWs contact and collusion with each other to plan escapes. To overcome this, the rank groups were first separated into compounds within a camp until sufficient space in a particular rank group camp became available. In the four and a half years Tim Newman and his crew members were “in the bag”, the officers and NCOs were mostly separated and so had almost no opportunity to communicate with each other while in captivity. Tim and his crew spent their captivity in the following camps:

- Dulag Luft (Oberusel) – Reception & Interrogation Camp for Airmen – 6-8000 transit aircrew

- Stalag Luft I (Barth, Vogelsang Prussia) – approx 6000 aircrew officers

- Stalag Luft III (Sagan, Lower Silesia in former Germany, now Poland) – held 10,000+ aircrew officers

- Stalag Luft VI (Heydekrug, German occupied Lithuania) – aircrew Warrant Officers & NCOs

- Stalag 357 Kopernicus (Thorn, now Torun Poland) – later became Stalag XX-A, aircrew Warrant Officers & NCOs

‘In the Bag’

Despite starting out as an officers-only camp, the Dulag Luft was not referred to as an ‘Oflag’ like other officer-only camps of the Wehrmacht (German regular army). The Luftwaffe (Air Force) had their own designation and nomenclature. A Dulag Luft (Durchgangslager der Luftwaffe) was an Interrogation Centre and transit camp run by the Luftwaffe that all airmen POWs were processed through after capture before being transferred in batches to, a transit camp in some cases, or a permanent POW camp (Stalag).

The Dulag Luft consisted of four large wooden barrack blocks, two of which were connected by a passage and known to the POWs as the ‘Cooler‘ (a gaol – 200 isolation prison cells). Each cell was 8 x 6 feet a 12 feet long, held five men to a cell that held a bed, a table, a chair and an electric bell to call the guard. On any given day the Cooler had 250 POWs confined. The third barrack block contained the German administrative headquarters, and the fourth was the interrogation offices, files and records. The capacity of Dulag Luft was supposedly 200 men as there were only 200 cells however the population frequently exceeded this as the number of Americans captured rapidly increased as the war went on.

Interrogation

On arrival at the Dulag Luft, POWs were graded as WHITE, GREY or BLACK. The grading depending on each man’s record of escape to date, their proven ability to be a nuisance, and willingness (or not) to co-operate. Tim Newman soon discovered all of the RAF officers and their NCOs had been graded as BLACK, i.e. they were considered by the Germans to be the worst prisoners and so had been separated into different compounds. The men were then searched, registered, photographed, issued a POW number and identity tag, and received rudimentary medical treatment as considered necessary.

All new arrivals were immediately placed in overnight solitary confinement (cell numbers permitting) until being interrogated the following day, a process often lasting many hours. The airman’s training for this situation required them to provide only their serial number, rank and name. However the interrogators who were well skilled in this art, often spoke perfect English and were well informed of each man’s situation, some having family details and place of origin details, etc. Many interrogators began by empathizing with injured POWs (having spotted bandaging) with “Oh! Bad luck! Well how are things at … (RAF .. name of the base)” from which the airman had come. After the interrogation the POW was returned to solitary and interrogated again the following day. Thereafter they remained at the camp temporarily, officers separated from Warrant Officers and NCOs, until taken via the hospital for a cursory health check and then to the Transit Camp. Their time at the Dulag Luft was generally seven to fourteen days.

‘ESCAPE’ was the name of the game (for most)

Escape to some extent was a conscience decision** upon which each man would have to weigh his own circumstances. He might consider the risk factors (what the impact might be on his family if he were caught or not to survive). An escaper had to be relatively free from injury so that any affliction did not jeopardise the potential success of others, so injury may rule a man out. A man may also have to come to terms with defending any decision to not participate in an escape or associated activity. On occasions, captives came from and underground organisation or had been working covertly for the Allies, e.g. Special Operations Executive (SOE) and so it was imperative these men did not take part in any activity that might bring their attention to their captors. Indeed, networks of other operatives in these organisation could be put at risk were a man to be caught, or interrogated following a failed escape attempt or discovery of a tunnel they had been helping with. These people very much needed to play the ‘grey man’, remaining in the background and not drawing any attention to themselves.

For these reasons, it was estimated those who expressed a desire to escape were just 25% of the camp population, and only 5% of those were considered to be dedicated escapers. The remaining 20% were prepared to work in support activities using whatever expertise or skills they had to contribute to the successful escape of others. Being involved, although not without considerable risk, was also considered to be beneficial for focusing the mind on something positive, keeping busy and doing stuff rather than fixating on the perceived hopeless of one’s predicament.

To a lesser extent, a few POWs suffered from a more recognisable phobia that precluded their inclusion in any below ground activity or escape – claustrophobia. To have a man panic underground whilst attempting to negotiate a narrow tunnel, could prove disastrous for the structural integrity of the tunnel, and the security of others involved and so these, mostly self-declared, were ruled out of escapes. The volunteer escaper also needed to be free from serious injury. A concealed injury could inhibit a man’s own ability to escape or become a liability to others he was escaping with and thereby potentially jeopardize their chances of success.

But whether an escape was successful or not, any Kriegie who got beyond the perimeter wire and remained at large for any period of time, made an important contribution to the war effort by tying up enemy resources in his re-capture. Escaping en masse could be a massive problem for the Germans. However in reality the odds against a successful escape by one man or many, started from a low base. The odds were against Kriegies whose only tools really were cunning, inventiveness, and improvisation all of which were thwarted more frequently by the Germans as the war ground on and German security personnel and systems of detecting escape activity improved. For an escaping Kriegie to achieve a “Home Run” (return to their home country) became a rare occurrence.

Start as you mean to go on …

Dulag Luft had been an eye-opener for POW #459 Pilot Officer Tim Newman. When he and his crew arrived at the Dulag Luft, escape seemed to be the principle pre-occupation of the majority of the inmates, the crew being shoulder tapped for digging duties almost as soon as they arrived. With upwards of 6000 Kriegies of various nationalities in the Dulag, the newcomers soon discovered there were numerous tunnels underway, as well as random opportunist escape attempts that occurred seemingly at will, and spontaneously. Tim had no inhibitions about escape; if he got the chance he would be into it like a robber’s dog! In fact he started from the outset as he meant to go on.

Keen to help in the tunnelling activities, he also participated in a couple of opportunistic, but unsuccessful, overt escape attempts, one on a vehicle that didn’t get out the gate. Being an inexperienced escaper, his only foray beyond the perimeter wire at Dulag Luft was the result of a bold attempt to go through the front gate when a large number of American aircrew arrived and were milling around creating a commotion at the gate entrance. In the confusion of their arrival, Tim and couple of others took their chances and made a run for it into the surrounding trees. At this point in the war, the Luftwaffe almost treated escape and capture as some sort of sport with photos being taken after a capture and really not taking things too seriously at all. This would all change. Apprehended within half an hour, Tim had his first taste of solitary confinement in the Cooler on starvation rations, receiving seven days for his foray outside. With that experience behind him, it didn’t take long for him to learn the finer points of what it took to become a much more proficient in his escape techniques.

Uncharacteristically Tim and his crew spent seven weeks in the Dulag Luft however the sheer increase in the volume of airmen being shot down/captured was overwhelming the existing camps. On February 16, 1941, now Flying Officer (F/O) Tim Newman and 100 mixed ranks of Allied POWs were marched carrying their kit the short distance to the nearby town of Oberursel and a waiting train. They were being transferred to their first permanent POW camp, Stalag Luft I at Barth which was on the windswept and freezing Baltic Coast of Vogelsang in East Prussia.

When the column of Kriegies arrived at the station, it was noted the train windows had been wired shut from the inside and screens had been erected on the outside to cover the glass in an effort to foil escape attempts. As the Kriegies milled around the train under armed guard waiting to board, a number of were seen to be unobtrusively removing as many of the screws from the screens as they could without them falling off. Packed into the railway cars, the heat was turned up full and armed guards lining the corridors watching every move, the train departed for Barth.

The distance to Barth is about 720 kilometres from Oberursel and would take roughly 24 hours to reach. The train departed in daylight travelling at about 15-20 mph (30kph). During the journey Tim and an Australian POW, SQNLDR Malcolm Lewellyn McColm, RAAF conceived a plan to take their chances and make a bolt for it once it was dark. Around 20:30 (8.30pm) after some sixteen hours on the train that had travelled roughly 500 kilometres, the two officers had unobtrusively worked their way to the end carriage and unwired a window. In the darkness both squeezed through the window undetected and jumped, fortunately landing without serious injury. Tim learned later that a simultaneous escape had been taking place elsewhere on the train by four POWs. Unfortunately one had hit his leg on a signal post as he jumped from the train badly injuring it and barely able to walk. This effectively jeopardized his group’s escape as they could not leave him, and as a result were all caught the next day.

By the second day on the run, Newman and McColm had reached Pasewalk which is around 250 kilometres from Barth however their bid for freedom came to a shuddering halt when they were seen as they tried to circumnavigate the town. They were arrested and taken directly to Stalag Luft I at Barth, each receiving eight days in the Cooler on starvation rations for their trouble. McColm received an additional eight days for stealing a badge from one of the Wehrmacht Special Leader’s at the Dulag Luft.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Stalag Luft I – BARTH

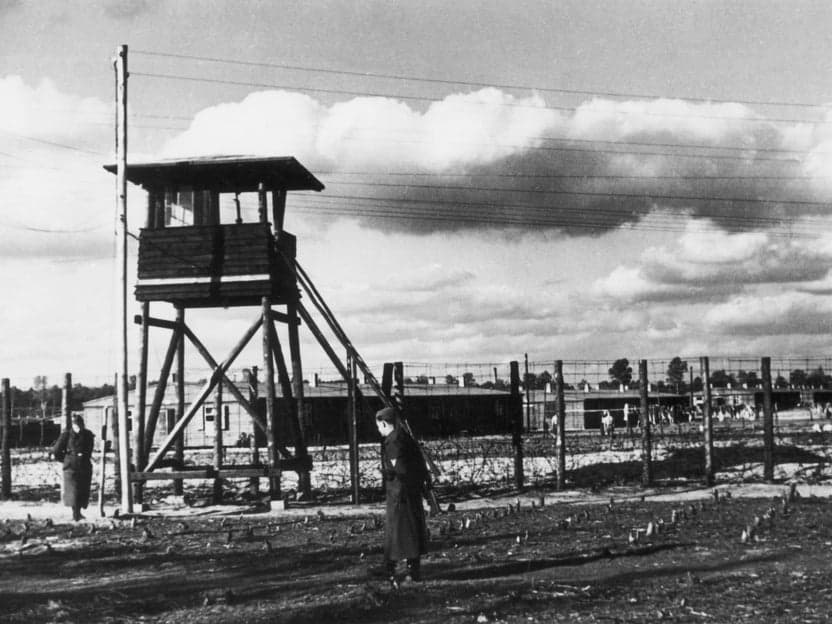

Stalag Luft I was opened in 1941 to hold British officers. The camp was situated on a strip of barren land jutting out into the Baltic Sea, about 105 miles northwest of Berlin. Three kilometres south of the main gate was a massive Lutheran church marking the northern outskirts of the village of Barth. A large pine forest bordered the west side of the camp and, to the east and north, the Barth Harbour was less than 1500 meters from the perimeter fence.

Surrounding the camp was miles of barbed wire, erected in two rows four feet apart, attached to 10 foot (3.5 mtrs) posts. Every hundred meters was a guard tower manned 24/7 and gave the guards an unobstructed view of the entire compound. Each tower had a mounted machine gun and a pair of spotlights.

The camp was divided into five separate POW compounds. There were five prison compounds: South and West, North 1, North 2, and North 3. A sixth compound, the Vortlager (German compound), was central and contained the Kommandanteur (camp HQ and Kommandant’s quarters, a medical treatment room and hospital (Lazarette), a jail (aka the ‘Cooler’) plus the officers and guard’s barrack accommodation. All the buildings were well constructed, even surrounded with green grass and attractive shrubbery. “The Oasis” as the prisoners called it was in stark contrast to their own compounds.

Dig, dig, dig …

The East Block at Barth had been completed about March 1941 and anyone who was placed in this block was immediately co-opted for tunneling duty. The block was around 20 feet (6 meters) from the perimeter wire and so tunnels were started as soon the first with

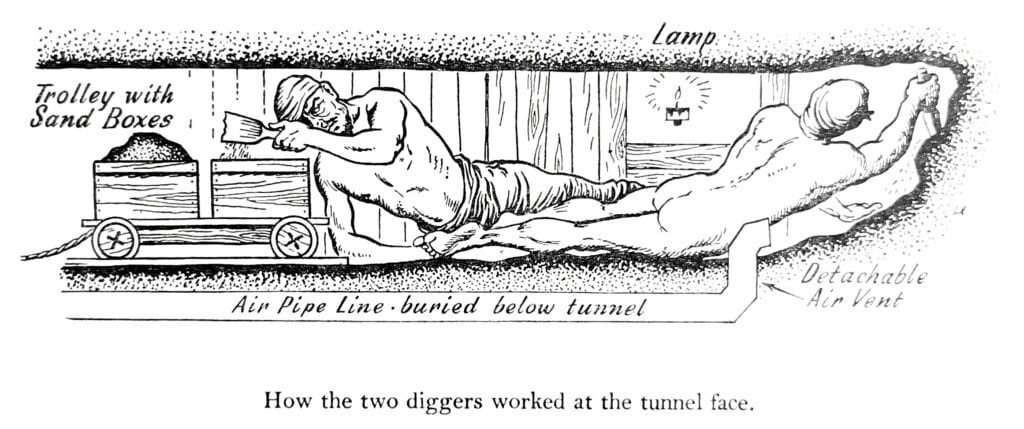

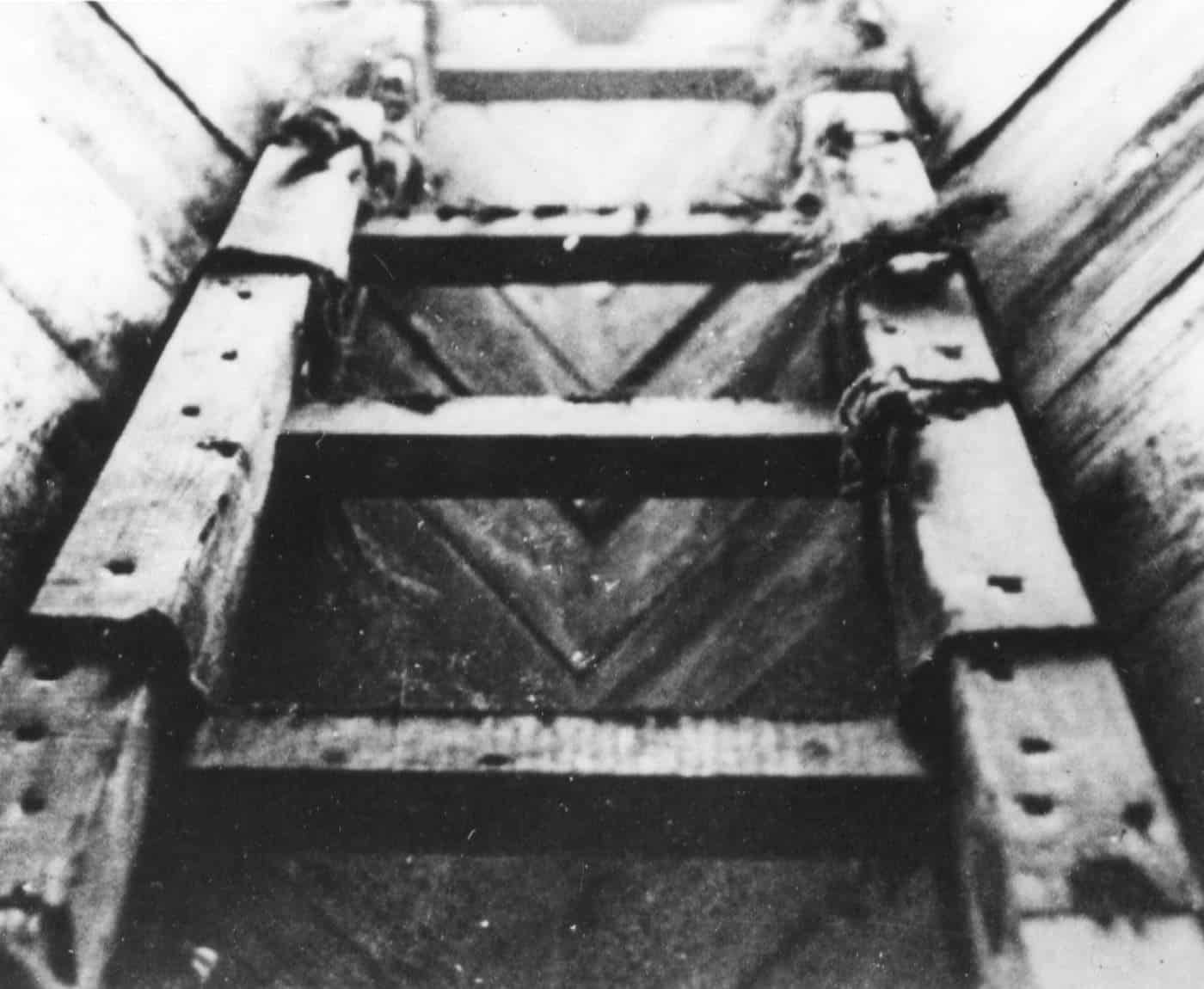

The tunnel trapdoor covered a gap of about 12 inches (30cms) between the hut floor and the ground level. This was screened from external view by siting the tunnel entrance under the huts only cooking and heating stove. It was bitterly cold, but the men would go down naked except for a loincloth using fat lamps for illumination. The lamps consisted of a little Marmite tin filled with saved food fat collected off the top of the soup, and a wick of plaited string, the outside being a glass bottle with the top and bottom cut off, capped with a wooden top and a handle. The men would dig for 30–45 minute stints using basic tools such as pieces of metal, sharpened pieces of wood and KLIM milk cans fashioned into scoops. The sand was put into the aluminium bowls used for personal ablutions and surreptitiously dispersed under the accommodation huts. Eventually the tunnel was about 100 feet (30mtrs) in length meaning it had progressed beyond the perimeter wire. Finally it was ready on 19 August for the break-out.

On 20 August 1941, Sqn Ldr’s Malcolm McCOLM, RAF and Charlie LOCKETT, RAAF together with F/O Tim NEWMAN were to be the first three in the tunnel and to make the break through outside the camp. Dressed to pass as Swedish sailors in uniform trousers, polo-necked sweaters, and hats they made themselves, the group also had camp-made compasses, a silk map McColm had managed to keep when he was captured, and a local map copied from one obtained from the Germans. Each man had some food they saved and five Reichsmarks between them. The three had agreed to rendezvous in a field not far from the perimeter and then travel together to Lubec. If they were split up, the plan was to rendezvous at a rail crossing about 2kms from the camp.

Once the tunnel was broken open first out was McColm, then Lockett followed by Newman. Lockett had been seen coming out as a sentry in a guard tower scanned the area with a spot light and was immediately fired upon. The hail of machine-gun bullets missed him as he as bolted into the darkness. Newman had failed to reach the field and so McColm and Lockett made haste hoping for a rendezvous at the rail crossing. But Newman never showed, he had actually run in the opposite direction to avid the machine-gun fire.

The Germans arrived at the West Block about 20 minutes later and finding nothing obvious, ordered everyone out of the huts to be head counted and the huts searched which soon revealed the absence of three POWs.

The following is P/O Tim Newman’s own account from his M.I.9/S/P.G. debrief report:

“I was last out and hearing some shots fired I ran off alone as fast as I could. I was dressed as a workman and wore a pyjama coat dyed blue, Air Force trousers and a cap made out of a check scarf, the peak of which I had painted black with boot polish. I was without money or forged documents and had only a small amount of food which I had saved up. My aim was to reach Rostock, but soon after I got out of the camp I lost my way in the marshy area surrounding Barth. Eventually I found I was on the wrong side of a small river and had to retrace my steps which entailed walking through the village of Barth. Then I set off in a south-westerly direction and when I reached Dunngarten, I hid myself under some stooks in a field and went to sleep. Soon afterwards I was found by a farmer who took me to the police in the village. I was taken back to the camp.” (Stalag Luft I).

McColm and Lockett after walking at night for several days, hid in a train’s coal truck and rode the rest of the way to Lubec. With the aid of a helpful Swedish sailor, they were smuggled aboard and stowed away on a Swedish freighter. Unfortunately Lockett having gone ashore again that night was caught and handed over to the local police. McColm was found a couple of days later in the ship’s anchor chain locker, after the ship had sailed. The captain turned the ship around and McColm was handed over to the authorities. By the 1st of September, Lockett had been interned in Oflag X-C at Lubec, while McColm and Newman were returned to Stalag Luft I at Barth. Both were given a seven day sabbatical in the Cooler on starvation rations for their trouble. McColm having proven himself to be a serial escaper and to the Germans therefore a decided threat, was soon after dispatched to Oflag IV-C (Colditz Castle), the prison from which there was allegedly no escape. There were very few escape attempts from the West barracks after this.

Tim Newman and Malcolm McColm emerged from their ‘hell hole’ to the cheers of his fellow POWs, both somewhat thinner, if that was possible. Tim reckoned the Cooler was akin to living in a refrigerator and although weak from a lack of food was none the worse for wear. Thereafter they tended to keep a lower profile as Colditz was likely to be the next destination if they persisted in escaping.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Most POW camps, particularly Lufftwaffe camps permitted their ‘guests’ to indulge in various recreational activities. Sports were high on the list, even golf (minus the links), board games, cards, musical instruments, a library was usually in evidence in most camps, as was a theatre of some sort for amateur dramatics – the Germans enjoyed attending these despite being the target of the barbs and witticisms that often sailed over their heads. While the POWs were playing sport or amusing themselves with recreational pursuits, they were not escaping mused the Germans, or so they thought.

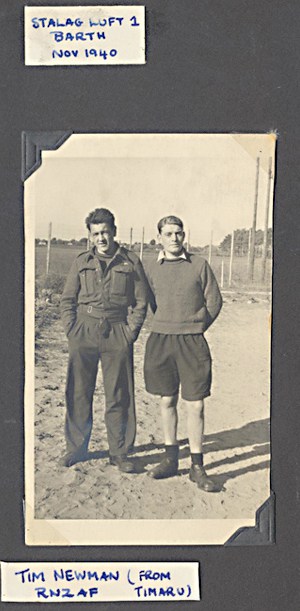

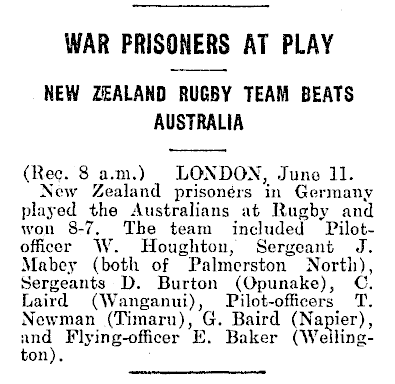

Tim Newman had been a pretty handy rugby football player while at Timaru BHS and so was selected to make his international debut for New Zealand against a scratch Australian fifteen – of POWs! Thankfully they won or we would still be living it down.

Stalag Luft III – SAGAN

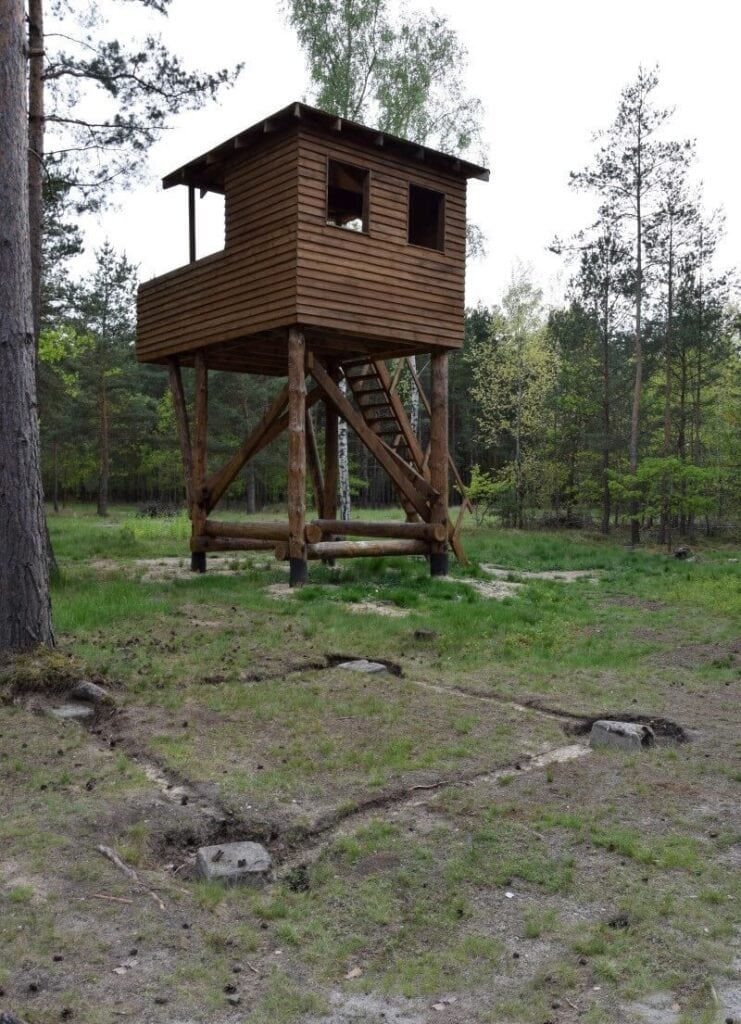

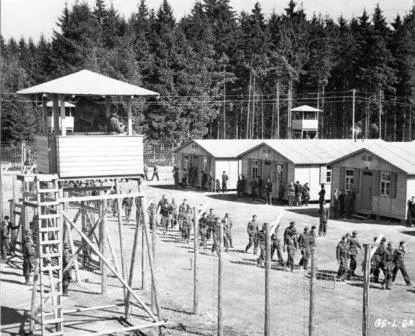

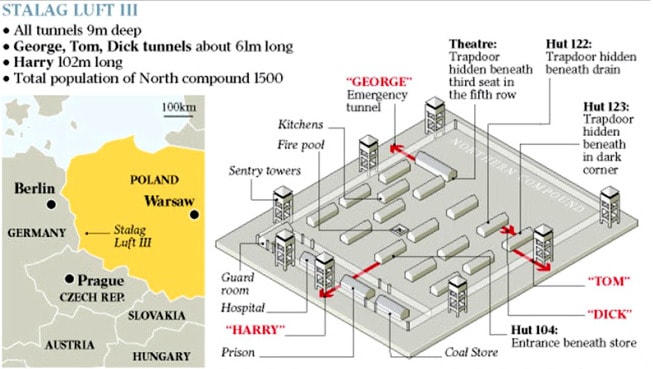

Sagan (Żagań) is in Upper Silesia, then a former Polish territory occupied by Nazi Germany. The new camp, Stalag Luft III (Sagan), or Stammlager Luft III to give it its proper German title, was to be one of the new types of POW facilities, a ‘state of the art’ camp constructed to be escape proof, to house the ever increasing number of allied airmen being captured daily, as Bomber Command maintained its offensive against German occupied Europe and Germany itself.

Stalag Luft III was located about 160 kilometres south-east of Berlin, sited in a thick pine forest that concealed the camp on three sides. The Sagan township and railway station was approximately 750 meters south of the camp. Designed to hold up to 10,000 POWs, the camp covered 59 acres and was surrounded with eight kilometres of barbed wire perimeter fencing.

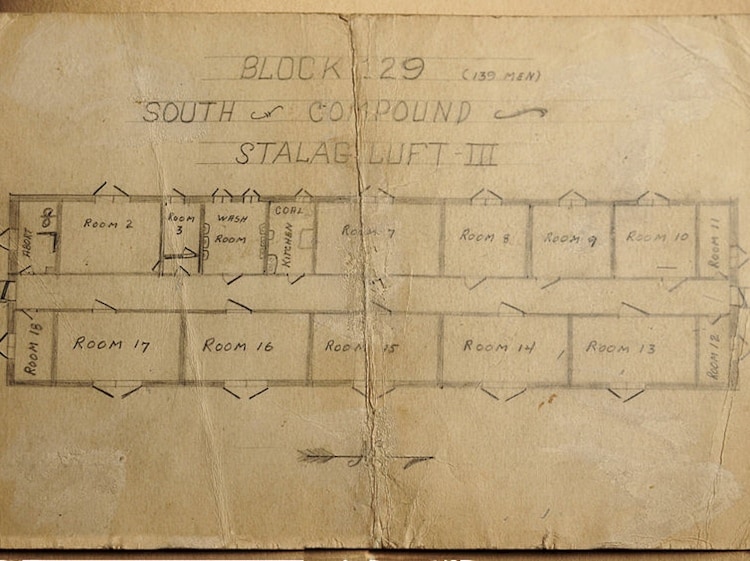

State of the Art

Himmler decided that the Sagan camp would be a ‘state of the art’ camp which would make it virtually escape-proof. The site selected for Stalag Luft III was deliberately chosen for its sandy soil to make tunneling very difficult. The camp initially had two compounds eventually growing to five compounds that could handle in the order of 11,000 POWs. The East Compound was opened in March 1942 to hold British and Commonwealth officers, with the Centre opened a month later to hold British and Commonwealth NCOs, however, these were replaced by USAAF personnel. The North Compound for British and Commonwealth air force officers opened on 29 March 1943. A South Compound for Americans was opened in September 1943 together with an overflow camp situated at Belaria, some five kilometres west of Sagan. With significant numbers of USAAF arriving the following month, construction of the West Compound for US officers was begun and opened in July 1944.

^^^ NORTH ^^^

Belaria had been a cadet training area for the Wehrmacht before it was turned into a POW camp. The camp had six ramshackle buildings in two small compounds surrounded by rusty barbed wire and watchtowers, each one equipped with a mounted machine-gun and a spotlight. By 1944, Belaria consisted of 8 accommodation blocks, each with an ablution area including washbasins, 3 or 4 showers (cold), and a urinal. Belaria also had a Cooler, a ration store with kitchen attached, a lazaret and a communal abort (toilet) … an 8-holer in two back-to-back rows of seats.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Time spent on reconnaissance is rarely wasted“

The Eastern Compound at Stalag Luft III was opened in March 1942. The first POWs were an advance party of 100+ RAF officers purged from the overcrowded Stalag Luft I at Barth. Numbers increased as more batches of prisoners of mixed ranks (Warrant Officers and NCOs) were caught and shipped from other camps or directly from the Luftwaffe’s Dulag Luft at Oberursel near Frankfurt-am-Main. The construction of a second compound, the North, allowed for the officers to be separated from the men who were eventually moved right out of Stalah Luft III to other NCO specific camps. Some NCOs volunteered to remain with their senior officers as Batmen and so were accommodated in the officers’ compound.

By March 1943 the North Compound was ready for occupation. A theatre was yet to be completed and so on the pretext of providing volunteers to assist with building this and to prepare the huts for occupation, some of the key escape planners were included in a work party that was permitted several hours access to the new compound. This was an opportunity for them to recce the new compound in detail, assess the buildings inside and out for likely tunnel entry/exit points, note the obstacles to be avoided, check lines of sight, pace out distances, record angles and direction, and to generally take a closer look at the surrounding forest and lay of the land outside the perimeter fence.

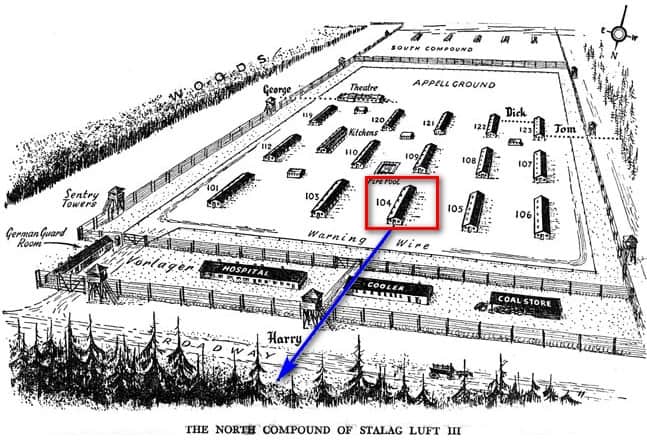

NORTH compound

By the time transfers in to the new North compound were completed, there were in excess of a 1000 mostly RAF and Commonwealth aircrew officers (most were Flight Lieutenants), two thirds of whom were keen to get stuck into tunnelling and escape preparation activities.

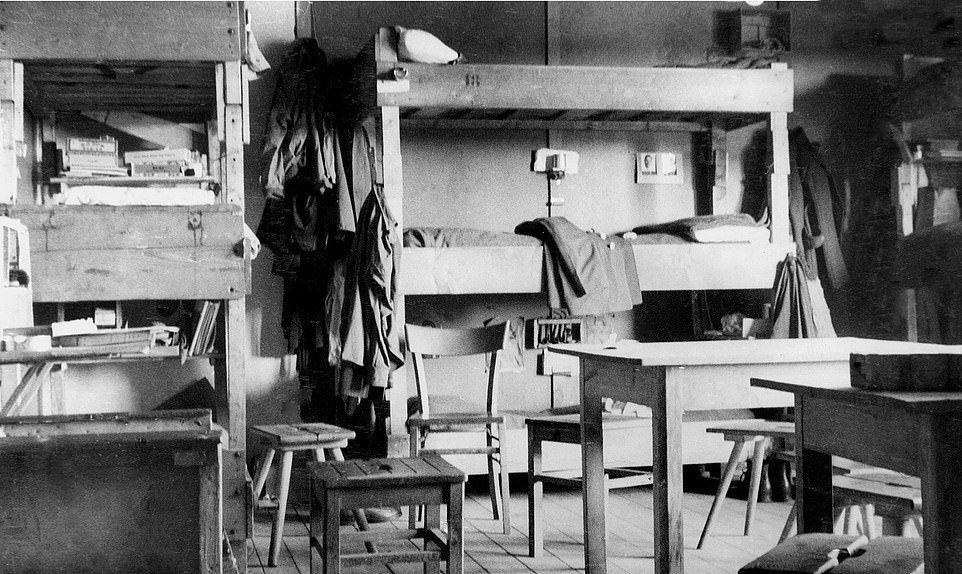

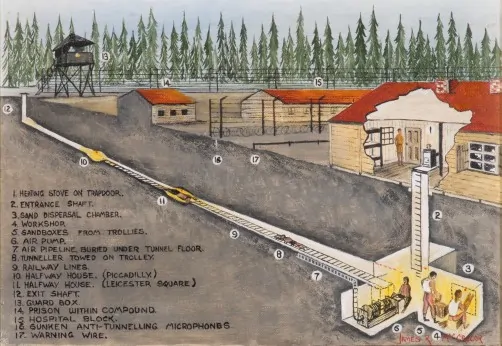

POW accommodation consisted of 15 pre-fabricated wooden huts, 14 of these being self-contained barracks blocks measuring 10 feet x 12 feet (3.0 x 3.7 mtrs) which could accommodate 1,175 POWs without overcrowding. Elsewhere in the compound was a kitchen, a couple of stores houses, one of which was designated a Red Cross parcel/box store, and a fire-fighting water pool.

Each hut was divided into 16 rooms which housed around eight men in each, plus three sets of private quarters for the senior officers. Each hut could hold 72 officers and 12 Other Ranks (these were NCO airmen who volunteered to act as Batmen for their officers). Each hut also had an abort – urinal and two toilet bowls, a bathroom with six porcelain hand basins, and a kitchen with one cooking stove.

Physical security

The compound’s perimeter fence was a double row of barbed wire, 2 meters apart and around 3 meters high. The two meter gap between the fences was filled with coils of barbed wire about a meter deep. Guard watch towers were spaced every 150 meters around the perimeter, each fitted with a machine-gun and a hand operated search light. Inside the inner perimeter fence was a warning rail (later replaced by wire) sited about 3 meters from the inner fence and half a meter high. While the guards were not exactly the cream of the Luftwaffe, to cross this rail/wire or even stand on it was an automatic invitation to be shot at (to wound only). A ‘shoot first and ask questions later’ mentality was undoubtedly applied by some trigger-happy guards as the records in the UK National Archives show, reports from SBOs to the Kommandants of all POW camps siting cases of prisoners being unnecessarily wounded or killed.

To deter tunnelling activities, the camp was the first to have seismographic microphones installed to detect tunneling activity. These were imbedded 3 meters into the ground between each perimeter watch tower, the Luftwaffe believing that with these, escape from this ‘state of the art’ camp would be impossible.

Vorlager (German compound)

Across the northern perimeter of the North compound was the Vorlager, a separate fenced compound prohibited to the POWs unless under armed escort. The Vorlager housed the German’s Guard Room, a Lazarette, Cooler and a coal store. The camp was accessed by a dirt road that ran east-west along the Vorlager’s northern perimeter with the camp Entrance Gates sited near the eastern corner beside the Guard Room.

Kommandanteur (Camp HQ)

The Kommandanteur was the collective name for the office of the camp’s Commanding Officer (Kommandant), the officers quarters and camp guard’s barracks. These were all situated outside the compound perimeter, adjacent to what would later become the West Compound. Stalag Luft III’s Kommandant was Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich von Lindeiner-Wildau, a decorated World War I veteran who had a compliment of some 800 Luftwaffe guards and staff with which to run his camp. Many of these however were too old for combat duty, younger airmen who were being rested after long tours of duty or those convalescing from wounds. Because the guards were Luftwaffe personnel, the prisoners generally received far better treatment than camps guarded by the Nazi Wehrmacht (Regular Army) soldiers, and a number of whom proved to be amenable/gullible to bribery by the Kriegies.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

First escapes from Stalag Luft III

Tunneling at Stalag Luft III was the dominant activity for the majority of Kriegies from virtually their day of arrival. In the officers’ compound, most of the newly arrived officers didn’t waste time in joining one of the tunnelling crews and sink themselves into any of the various escape activities to which they make a useful contribution, some having bought escape experience from previous camps. Apart from the few opportunistic escapes by individuals or small groups (most unsuccessful), several more audacious and successful mass escapes had been made during the early days at Stalag Luft III.

Delousing Party – June 1943

The Delousing break-out was the first mass escape attempt by allied aircrew officers of both British and American nationalities held as POWs during WW2. The plan was masterminded by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell RAF, the architect of the ‘Great Escape’ in 1944.

Main Party – On 12 June 1943, a party of 24 officers were escorted by two German speaking Kriegies disguised as uniformed guards were led out of the North compound, through the Main Gate of Stalag Luft III for delousing. Once outside, two of POWs who were pilots, put on the uniforms of the bogus guards while the remainder fled into the forest. Unfortunately the two uniformed POWs were captured at a local air field trying to start an aircraft – but the Germans were very fond of taking photographs of recaptured escapers and the means they used to escape, in these early days and so was more of a novelty than an act of war and so the punishment regime for the escapees, once their captor’s pride had been flushed with copious photographs of their good work, was very much lighter than it became later in the war. All twenty-six escapers were recaptured, many within hours. Twenty-four of them were returned to the camp, but the two uniformed ‘guards’ were sent to Oflag IV-C (Colditz) for attempting to steal the aircraft.

Second Party – A second party of six officers, again escorted by a fake guard, also attempted to escape whilst on route to the neighbouring compound shortly after the Main Party had left, however the forged pass carried by one man was out of date and the alarm was raised. All participants in the escape were held for a period of time in solitary confinement.

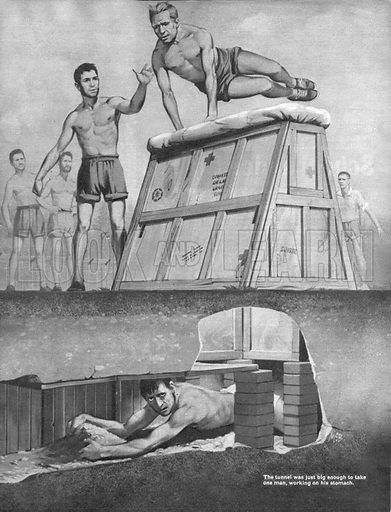

Wooden Horse, October 1943

After 114 days of tunneling, officers F/L Eric WILLIAMS RAF, F/L Oliver PHILPOTT, RAF and LT Michael CODNER, RA (Royal Artillery) escaped through a tunnel in the East Compound of Stalag Luft III on 29 October 1943. This was dug while concealed by a wooden vaulting horse they had manufactured from Red Cross parcel boxes. The horse concealed two tunnellers and their tools inside. Each day the vaulting horse was carried outside and placed in the same position over a concealed trapdoor near the perimeter fence. Once in position, gymnastic recreation began with vaulting over the horse while the two tunnellers entered the tunnel and continued digging. At the end of the session, the tunnellers and the sand they removed in bags suspended inside the horse, were carried back to their hut. After several months of digging, the tunnel cleared the perimeter fence allowing three to make their escape under the cover of darkness. The three men walked for miles before travelling by train to a coastal port, where two stowed away aboard a Danish ship, and the other on a Swedish ship that was bound for neutral Stockholm. All three eventually reached England, the only successful Home Run** by POWs to be made from the Eastern Compound of Stalag Luft III.

Note: ** A ‘Home Run‘ was declared when a POW had escaped from inside a camp and made their way all the way home to their parent country, without any external assistance such as from partisans or of an escape line.

Stalag Luft III – Organisation

With the opening of the North Compound, Tim Newman and his crew were purged from the overcrowded Stalag Luft I at Barth and temporarily interned at Belaria, a satellite holding camp of Luft III, or the 5th Compound as it became. After a short spell there, they were moved into Stalag Luft III main camp in March 1943.

Senior British Officer (SBO)

Irrespective of the camp, all Allied POWs came under the command and control of the resident senior ranking British officer, known as the Senior British Officer (SBO). The NCO’s and men who initially arrived with the officers as they progressed through interrogation, once separated were no longer under the direct control of the SBO and so were required to elect a Man of Confidence (MoC), usually a senior Warrant Officer or Flight Sergeant. The MoC was the men’s representative and the conduit for all information to and from the SBO and officers. The MoC also reported directly to representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who were responsible for inspecting the camps and hospitals and producing reports. The sorts of issues the MoC would advocate with the camp authorities on behalf of the men were matters related to camp routine, work schedules, discipline and diet. In due course the Warrant Officers, NCOs and men were transferred to separate camps specifically set aside for non-commissioned personnel and so retained this basic organisational structure by necessity. Additional men were appointed to assist the MoC as needed.

Harry ‘Wings’ Day

When Tim Newman and his cohorts arrived at Stalag Luft III, Wing Commander Harry ‘Wings’ Melville Arbuthnot DAY, RAF was the SBO at Stalag Luft III who oversaw the initial stages of planning for the ‘Great Escape’. A veteran of four previous escape attempts himself from earlier camps, Day had seen the failures of numerous un-coordinated escape attempts. Even successful escapers had come unstuck for the want of a real plan once outside the wire. He decided in order to maximized the chances of escape success at Stalag Luft III, each escape was to have the risks assessed, be properly planned, vetted and approved before any attempt was started, either that or the free-for-all that currently characterized escape attempts could un-necessarily cost lives and markedly affect the morale of their fellow POWs. Day had trialed the concept of an Escape Committee, a group of experienced escapers chaired by an experienced leader with a committee to plan, approve and manage every escape which involved a coordinating the activities of a number specialist to support the escape. Collectively this was known as the Escape, or X-Organisation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Previous escape attempts from Stalag Luft III’s East Compound had met with mixed success. Whilst the Delousing Party and Wooden Horse escapes were triumphs of morale, mass escapes from a tunnel rarely occurred due to its prior discovery. With more than 80 tunnels discovered at Stalag Luft III it was clear to the SBO a much more structured approach to tunnel escapes was required if the North Compound was to have any success.

To that end ‘Wings’ Day selected a self-assured fighter pilot with escape experience as well as a sound command of German among other languages, to head up the escape organisation at Stalag Luft III. Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell, DFC after his capture had been made part of the permanent British staff at the Dulag Luft, then under the command of SBO ‘Wings’ Day. Day had deputised Bushell to the then head of escape operations, S/L Jimmy Buckley RAF who was known as Big-X. The permanent staff’s duty was to help newly captured aircrew to adjust to life as a Prisoner of War.

Escape organisation

Big-X

Bushell had become an experienced escaper of three near successful attempts, was a fluent speaker of both German and French, and had gained greatly from the experience of working with Buckley. As a consequence, after he was transferred to Stalag Luft III, SBO ‘Wings’ Day selected Bushell as Big-X to chair the Stalag Luft III Escape Committee, or X-Committee.

Roger Bushell was a RAF Spitfire pilot, the CO of No.92 (Spitfire) Squadron when he was shot down on 23 May 1940 during the Battle of France. He, on a previous escape, had been hiding in Prague and was caught in the aftermath of the Heydrich assassination of which the Gestapo suspected Bushell of being complicit in. The French family hiding him were all executed by the Gestapo and Jack Zaphouk, his Czech co-escaper, was purged to Stalag IV-C, Colditz Castle. As a result, Bushell developed an almost pathological hatred of the Germans however, failed to distinguish between the ruthless and cruel Gestapo, and the less ardent types represented by Luftwaffe personnel, including the Kommandant of Stalag Luft III.

Rank references: G/C = Group Captain, W/C = Wing Commander, S/L = Squadron Leader, F/L = Flight Lieutenant, F/O = Flying Officer, P/O = Pilot Officer; LT = Lieutenant, Army or (N) = Navy.

X-Committee

Bushell’s X-Committee were the planners and vetted all escapes plans presented to them for consideration from others (and that of the SBO). The X-Committee comprised the following:

- F/O Clark Wallace ‘Wally, the Tunnel King’ FLOODY, RCAF (401 Sqn, RAF) – i/c Tunnel Construction, an ex-miner and the masterminded of the construction of all three tunnels.

- F/L George Randolph HARSH, RCAF (102 Sqn, RAF) – i/c Security of the three tunnels. Manage the Duty Pilots and Stooges, all other internal security measures in support of escape preparation and the collection of intelligence. George Harsh also had history; as a teenager he was a convicted of murderer in Canada who served a substantial period in prison. He was released to volunteer for war service and as it happened, acquitted himself exceptionally well in the internal security roll.

- LT (RN) Peter ‘Hornblower’ FANSHAWE, FAA (803 Sqn, Fleet Air Arm) – i/c of sand dispersal & personnel – ‘Penguins’.

Key personnel & departments

Bushell collected the most skilled forgers, tailors, tunnel engineers and surveillance experts and announced his intention to put 250 men outside the wire. This would cause a tremendous problem and force the enemy to divert men and resources to round up the escapers. His idea was not so much to return escapers to the UK but mainly to cause a giant internal problem for the German administration. Bushell went about this task with a typical single-minded determinedness, despite having been officially warned that his next escape and recapture would result in his execution.

An escape this big had not been achieved before and so meticulous preparations were made for this planned mass escape. As the pre-occupation of most POWs was escape, much of the camp’s activities were geared to acquiring maps, making ausweiss (passes), civil clothing from uniforms, producing photographs, acquiring money and of course tunnelling.

The X-Org created a number of departments to support the various escape activities, each one headed by a designated leader.

-

- F/L William ‘Wally’ David Gaynell McCAW, RAF (Little-X) – Roger Bushell’s deputy

- F/L Robert ‘Crump’ Gerald KER-RAMSAY, FAA/RAF – Floody’s Chief Engineer

- F/L Henry ‘Johnny’ Cuthbert MARSHALL, RAF – Floody’s Tunnelling Assistant

- F/L Desmond ‘Des’ Lancelot PLUNKETT, RAF – Map making team; 4000 hand drawn, copied and acquired maps.

- F/L Gilbert ‘Tim’ William WALENN, RAF – A graphic artist and designer, Tim’s forgery team was responsible for the production of fake Identity Cards/Photos & Passes. They were also responsible for procuring genuine IDs and Passes by bribery & blackmail from the guards. These two departments were nicknamed the “Dean and Dawson Travel Agency” after a well-known UK travel firm founded in 1871.

- P/O Frank ‘Johnny’ St. John TRAVIS, Rhodesian Air Force – Fat Lamps & Escape Kit manufacturing team, e.g. compasses (500 made) from fragments of broken bakelite gramophone records recovered from camp dump, melted and shaped incorporating a tiny needle made from slivers of magnetized razor blades. A touch of comedy was added to these – stamped on the underside of each compass was ‘Made in Stalag Luft III – Patent Pending’.

- F/L Thomas ‘Tommy’ GUEST, RAF – a Tailor by trade, Tommy arranged the modification of service uniforms into civilian suits and German uniforms, producing workmen’s clothing and other civilian type attire from sheets and blankets. These included 50 complete suits from converted uniforms plus several German uniforms.

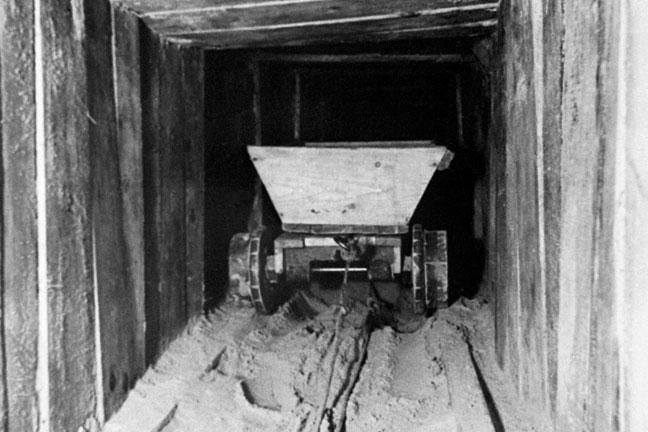

- P/O Ian Alexander ‘Digger’ MACINTOSH, RAF – known as the ‘ace’ carpenter, he managed construction of the tunnel rail system, the flat deck trollies and sand boxes, as well as shoring timber and anything else made from wood.

Note: One very capable cobbler among the POWs who could make and repair footwear, was tasked to go to all newly captured arrivals who were flyers and secure their flying boots. The rubber heels were then removed and substituted for wooden ones allowing the rubber heals to be used to manufacture counterfeit stamps for passes, documents, etc. for the escape attempts. He also helped to make or convert boots into shoes for any escape.

Y and Z Organisations

The Y-Org was a series of specialist departments spread throughout the huts. These specialised in producing forged escape maps, documents, letters and passes, making escape clothing (civilian suits, jackets, shoes, hats etc), procuring and/or manufacturing escape rations, and the equipment need for success – compasses, water-bottles, money, etc. The Y-Org coordinated the Duty Pilot roster to protect the various undercover activities. An escaper had to rehearse for the role, learn not to draw attention but also to look and act credibly whomever he was intending to portray, be that businessman, labourer, foreign national etc.

Getting out of the camp was only the first part of any escape. For escapers to be apprehended after months of tunnelling and preparation would be highly demoralising, not only for those caught but for others seeking to escape and providing escape support. Spot checks by local the Police and the Gestapo were a given, however could be fatal if an escaper was not adequately prepared. Anyone adept at drawing or painting was encouraged to the forgery department. Initially, all forged documents were produced entirely by hand drawing them using a brush and Indian ink, with rubber stamps being carved from boot rubber.

The Z-Org was responsible for maintaining contact with RAF intelligence in England. It debriefed all new POW’s arriving in the compound and was on the alert to any suspected of being planted by the Germans. Information was also collected from POWs who interacted with guards who were amenable to bribery and blackmail as a source of information. As the war progressed it became very important to find out what they knew and any useful information sent back to England by coded POW mail. Selected aircrew had been trained in information gathering and to use coded messages (in letters) in the event they were caught.

Internal Security

The Kriegies day was structured around the morning and evening Appell – a parade to count heads and conduct a roll-call to ensure all POWs were accounted for and present. There were however many tricks developed by the POWs to conceal the absence of a man/men. Appell in the morning was at 0800 (8.00am) and 1700 (5.00pm) in the afternoon. Hut lighting was controlled by the Germans and was switched off at 2100 (9.00pm). At this time the Kriegies were locked in their huts, and the compound floodlit. apart from these timing, appell could occur at any time for any reason, the most common being a hut search conducted by specialist Abwehr personnel, looking for a suspected tunnel entrance, or a search for evidence of escape activity. Around these parade timings, escape preparation and particularly tunnelling, carried on in some form 24/7 so it was essential internal security measures among Kriegies was rigidly adhered to and strictly enforced.

Under threat of a court martial, Bushell had most emphatically banned the use of the word “tunnel” in case it was inadvertently overheard by the Germans, or could be communicated to them by an unknown informer from within the Kriegie’s ranks.

Compound access control

Duty Pilot & Stooges – F/L George HARSH RCAF controlled the security arrangements, managing and training the Duty Pilots and Stooges. It was a Duty Pilot’s role to log every German in and out of the compound so that none could conceal themselves to discover what might be happening in the compound. Positioned to record these, the Duty Pilot would alert those in the compound via silent signals passed through a network of Stooges (look-outs) to the each hut’s Little-S of an impending threat. As long as a German lurked inside the compound he was shadowed by a Stooge who could alert the network. The command of “Goon up” from Little-S was the signal to conceal the tunnel trap, cease any support activities, and conceal the evidence. Reaction and concealment was practiced until down to a fine art, and able to be achieved in 10 seconds. In addition each hut that concealed escape activities had a Little-S positioned at the entry steps (reading, playing cards etc) whose job it was to question every person who wished to enter the hut, “what is your business?” If Germans, to delay their entry as long as possible to ensure maximum time to conceal any illicit activities.

Goons and Ferrets

Goons – German guards were universally known as ‘Goons’, a nickname which puzzled them. (When asked, a captured officer said that it stood for German Officer Or Non-com[missioned officer]. Annoying the guards was a popular if not risky past-time called ‘Goon or Jerry Baiting’. This was practiced in most camps with various degrees of enthusiasm, basic school-boy humour being the basis of this. To outwit the Germans, to embarrass or humiliate them by subtle means was altogether a different skill as this required guile and cunning, and a greater intelligence than their captors. The compounds and buildings were subjected to regular snap sweeps by camp’s staff in order to deter tunnelling activities and/or to discover illicit materials that might aid escapes. All escape preparation relied heavily on the earliest warning possible to prevent compromise or the loss of men, time spent on preparation, loss of equipment and materials required for any attempt. While the watch tower Goons manned the towers 24/7 watching for any overt attempts to scale the perimeter wire, the primary threat to escape preparation came from the interminable snap checks and inspections of the huts and compound by the Ferrets.

Ferrets – The Abwehr (security intelligence personnel) were add to the camp staff as a specialist search team. These were nicknamed ‘ferrets’ by the Kriegies because of the overalls they wore and the manner in which they ferreted through the a very efficient Luftwaffe Oberfeldwebel (Warrant Officer) Sergeant-Major Hermann GlEMNITZ, an older man who had been a pilot during WW1. The POWs considered Glemnitz to be the ferret who posed the greatest threat to their security.

The ferret team was headed up by an enthusiastic Abwehr Corporal who routinely swooped on the compound or a hut, turning the occupants out for two or more hours while they ratted through every inch of a building, its ceiling and underfloor, looking for evidence. The huts being elevated off the ground to deter tunnelling presented the ferrets an additional opportunity to gain information from unknowing Kriegies. Curfew for the prisoners was 2100 (9.00pm) at night, and all prisoners were locked in the huts until appell at 0800 (8.00am) next morning. No person was permitted outside the huts between these hours or they would be shot! Ferrets on occasions would concealed themselves at night under a hut to listen to the prisoners talking, in the hope of hearing something useful regarding tunnels, namely an entry point, or to find out what was being planned. This practice did not last as all new POWs arriving at the camp were briefed accordingly, the hut occupants being particularly guarded in what they said and only in hushed tones.

‘Rubberneck’

The nemesis of all POWs at Stalag Luft III was an unpredictable and fanatical ferret named Gefreiter (Corporal) Karl GREISE whom the Kriegies nicknamed ‘Rubberneck’ since he appeared to have eyes in the back of his head and was particularly adept at spotting evidence of escape activity. Greise was Glemnitz’s 2 i/c, and always seeking opportunities to impress Glemnitz. Glemnitz and Greise managed to expose no less than 80 tunnels in Stalag Luft III’s five compounds by war’s end however, the ‘Great Escape’ tunnel was not one of them.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When evidence of excavation was detected, e.g. the sand taken from tunnel was of a light yellow colouring which differed markedly in colour from the darker surface soil in the compound, if spotted the ferrets would go into overdrive searching for the source. One method used for fast results in the initial months of the camp opening was to drive heavy vehicles around a hut suspected of being the source of a tunnel entrance, hoping to reveal any tunnel or galleries by collapsing them under the weight. This led to a more sophisticated method of detection. A suspected hut would have a trench dug along its length on the side closest to the perimeter fence. If the tunnel was not immediately discovered, the bottom of the trench was then probed with steel rods to hopefully reveal a break-through into a tunnel at a deeper depth. The result of this was to dig tunnels even deeper. In Stalag III’s new North Compound, being a ‘state of the arty’ POW facility, the installation of seismic microphones to detect tunnelling activity was a game changer, one that Rubberneck and his cronies no doubt relished as the difficulty of tunnelling without detection was greatly increased. The answer: tunnels would have to be dug to an unprecedented depth to avoid detection.

Tunnels – TOM, DICK, HARRY

As Bushell formulated and reviewed the plans for various escape attempts, he reasoned that the Germans would not expect three tunnels to be dug at the same time however were more than likely to discover at least one, and so the odds of success by having an alternate tunnel dug would be much greater. Bushell’s final plan called for three tunnels to be dug simultaneously, each to be named TOM, DICK and HARRY. One of these he planned get 200 escapers through. All three tunnels of these tunnels in the North Compound were started around April-May 1943.

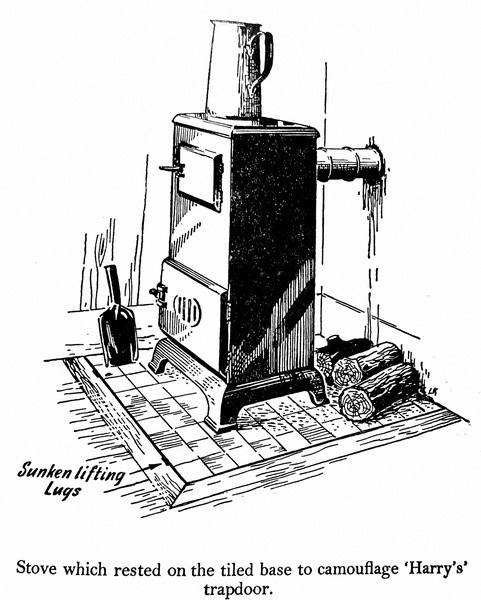

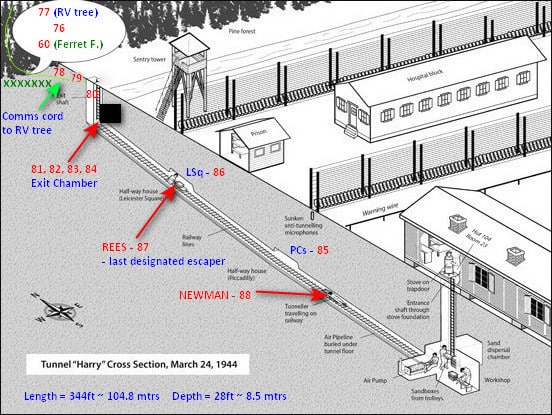

The huts in the North Compound were built on 60cm brick and concrete pillar foundations which permitted a clear view underneath. The foundations were imbedded in the ground and provided a means for creating a tunnel entrance by piercing the centre of the foundation. The entrance for TOM began in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney in Hut 123, through the concrete foundation and extended west into the forest. The entrance to DICK was hidden in a drain sump in the centre of the concrete washroom (bathroom) floor of Hut 122. When closed and sealed, the entrance was concealed under some 0.6 meter of water in the sump. DICK was to be dug in the same direction as TOM as it was thought the hut would not be a suspected tunnel site as it was further from the perimeter wire than the others. The Germans never found this tunnel which later was used as a workshop and to store equipment, clothing, rations etc, stockpiled for an escape. It was also used to hide excavated soil from the other tunnels when all other locations were at capacity. In Hut 104, a caste-iron cooking/heating stove that all huts had that stood on a tiled concrete slab. When the stove and slab were removed, the entrance trap door to HARRY began by penetrating a concrete foundation and excavating a shaft to an unprecedented depth of 6 meters.

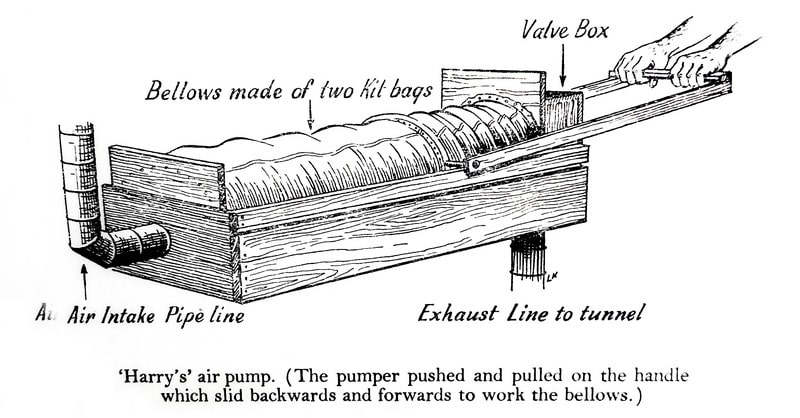

Both of these eventualities meant that work on TOM became the priority and work on HARRY was suspended. With 40 feet to go to complete TOM, the speed and concentration on TOM meant mistakes were made and shortcuts taken. The result was the detection of different coloured sand by the ferrets plus an inordinate number of Kriegies had been observed moving carrying Red Cross boxes (full of sand). This led to a concerted search of the huts at that end of the compound. Although nothing was found, increased searches of the huts were carried out by the ferrets looking for any tell-tale evidence of tunnelling. The sneaky tactics of the Ferrets sometimes involved concealing themselves in the ceiling or under the floor of a hut while the occupants had been ordered to appell. This meant that after the appell, the occupants would have to conduct another comprehensive search of their hut for concealed ferrets before it was clear to recommence tunnelling and escape preparation activities.