MILLION DOLLAR VC ~ Thomas Henry KAVANAGH, V.C.

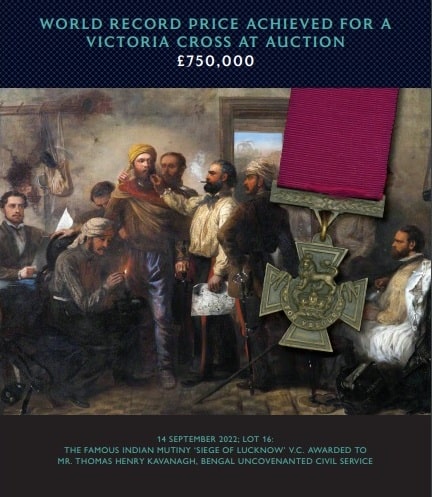

A world-record price was recently paid for this fine singular specimen of gallantry, one of only five civilian V.C.s to be awarded (who said civilians didn’t get the VC?). The hammer price of £750,000 was paid by an undisclosed collector on September 14, 2022 at the Noonans Mayfair (formerly Dix, Noonan & Webb) medal auction in London.

This famous Indian Mutiny ‘Siege of Lucknow’ Victoria Cross awarded to Irishman Thomas Henry Kavanagh realised a grand total of £930,000 ($1.075 million) with the 24% buyers premium was added.

It was the first civilian V.C. of five to be awarded and was one of only two that is not currently in a museum. The estimate was £300,000-400,000.

The previous record stood at £840,000 for the V.C. won by a naval hero who allowed his ship to be torpedoed so he could lure a German U-boat close enough to sink it during World War One. Vice Admiral Gordon Campbell’s decoration achieved a hammer price £700,000.

The famous Indian Mutiny ‘Siege of Lucknow’ V.C. awarded to Mr. Thomas Henry Kavanagh, Bengal Uncovenanted Civil Service.

Serving under the orders of Lieutenant-General Sir James Outram in Lucknow, Thomas Henry Kavanagh was decorated with the highest honour for undertaking an epic quest to escape the surrounded Residency at night, cross enemy lines, make contact with the camp of the Commander-in Chief, and then using his local knowledge, guide the relieving force through the city to the beleaguered garrison by the safest route. Conceiving the plan himself, Mr Kavanagh, an Irishman employed as a clerk in the Lucknow Office prior to the Siege, volunteered to leave the safety of the Residency disguised as a Sepoy irregular soldier, accompanied by a Brahmin scout. The pair jostled past armed rebels through the narrow Lucknow streets, talked their way past sentries in the moonlight, forded deep rivers, tramped through swamps and narrowly avoided capture after startling a farmer who raised the alarm. On finally reaching a British cavalry outpost, Kavanagh delivered Outram’s vital despatch to Sir Colin Campbell and ably guided his column to the relief of the Residency garrison. The first of just five civilians to have been awarded the V.C., he was further rewarded with promotion to the gazetted post of Assistant Commissioner of Oude and was presented with his cross by Queen Victoria in a special ceremony at Windsor Castle.

V.C. London Gazette 6 July 1859

Thomas Henry Kavanagh, Assistant Commissioner in Oudh, Bengal Civil Service. Date of act of bravery: 8th November, 1857.

‘On the 8th November 1857, Mr. Kavanagh, then serving under the orders of Lieut.-General Sir James Outram in Lucknow, volunteered on the dangerous duty of proceeding through the city to the camp of the Commander in Chief for the purpose of guiding the relieving force to the beleaguered garrison in the Residency – a task which he performed with the most chivalrous gallantry and devotion.’

~~~~~~~~~~~VC~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thomas Henry Kavanagh was born on 15 July 1821 in Mullingar, Co. Westmeath and was educated in Ireland. His father was the Bandmaster of the 3rd Foot (Buffs), but little else is known about his early life. When still in his teens he entered the Indian Uncovenanted Civil Service in the Office of the Commissioner of Meerut and in 1849 was posted to Oudh with Sir Henry Lawrence, becoming a member of the Punjab Commission.

Kavanagh went on to Lucknow with Lawrence and was a clerk there in one of the civil offices at the time of the Indian Mutiny. His wife and four eldest children (ultimately they had fourteen children) were fortunate to be also in the Residency at that time although his wife was wounded by a shell during the siege and his youngest child died in the Residency as a baby. Still, in his diary Kavanagh gave thanks for their deliverance from the atrocities further south: ‘My family were staying in Cawnpore, and it was arranged they should spend the summer there with some friends, as houses were difficult to get in Lucknow then; but providence willed that my wife should differ with some people under the same roof, and she at once came to me at Lucknow. Thank God she did.’

~~~~~~~~~~~VC~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Residency at Lucknow was besieged from 30 June 1857 and Generals Outram and Havelock, with over 2000 troops, had fought their way through the city on 26 September intending to rescue the garrison and return to Cawnpore but they too were surrounded and obliged to defend themselves in places adjoining the Residency Entrenchment. During the first months of the siege, like many non-combatant civil service men, Kavanagh was fully engaged in the resistance, leading a group of fellow civil service volunteers as a mobile reserve around the most embattled parts of the fortifications, manning field mortars and counter-tunnelling against bomb attempts by the rebels. However, the situation at Lucknow had become critical by November and realizing that the chances of the second relief force coming up from Cawnpore under Sir Colin Campbell would be greatly enhanced if they had a guide who knew the environs of the city well, Kavanagh saw his chance for glory and planned to volunteer to go out and bring them in.

Having learnt that a spy had come in from Cawnpore and that he was returning in the night as far as Alumbagh with despatches to Sir Colin Campbell, he sought out the man and told him his desire to accompany him in disguise: ‘He hesitated a great deal at acting as my guide, but made no attempt to exaggerate the dangers of the road. He merely urged that there was more chance of detection by our going together and proposed that we should take different roads and meet outside of the city, to which I objected.‘ (How I won the Victoria Cross by T. Henry Kavanagh refers). Kavanagh was not to be deterred. That afternoon he volunteered his services through his immediate chief, Colonel Napier. Both Sir James Outram and Napier, the Chief Engineer, were against the hazardous enterprise initially. As Kavanagh was a tall man, with fair hair and blue eyes, the matter of his appearance was of particular difficulty, but Kavanagh persisted and Outram finally consented to the plan. Kavanagh returned to his quarters: ‘I lay down on my bed with my back towards my wife, who was giving her children the poor dinner to which they were reduced, and endeavouring to silence their repeated requests for more. I dared not face her; for her keen eye and fond heart would have immediately detected that I was in deep thought and agitated. She called me to partake, of a coarse cake, but, as I could no more have eaten it than have eaten herself, I pleaded fatigue and sleepiness, and begged to be let alone. Of all the trials I ever endured this was the worst. At six o’clock I kissed the family and left, pretending that I was for duty at the mines, and that I might be detained till late in the morning.

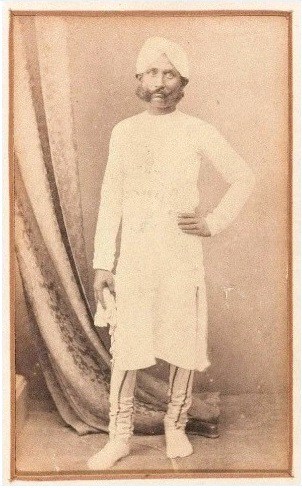

Kavanagh proceeded to a small room in the slaughter-yard where he disguised himself as a budmash or swashbuckler, with sword and shield, native made shoes, tight trousers, a yellow silk koortah (or jacket) over a tight-fitting white muslin shirt, ‘a yellow-coloured chintz sheet thrown round my shoulders, a cream-coloured turban, and a white waistband or kumurbund. My face down to the shoulders, and my hands to the wrists were coloured with lamp black, the cork used being dipped in oil to cause the colour to adhere a little.’ Thus attired he entered Napier’s room who did not recognise him. Outram himself daubed him once more with burnt cork and oil and he and Napier warmly pressed his hand with a few encouraging words. Then at half-past eight accompanied by Kananji Lal, the scout, Kavanagh was let through the British lines by Captain Hardinge and reached the right bank of the Goomtee. ‘I descended naked to the stream, with the clothes on my head rolled into a bundle. The first plunge into the lines of the enemy, and the cold water, chilled my courage immensely and if the guide had been within my reach I should, perhaps, have pulled him back, and given up the enterprise.’

On the other side in a grove of low trees they re-dressed and went up the left bank until they reached an iron bridge. Here they were stopped and called over by a native officer who was seated in an upper-storied house. ‘My guide advanced to the light and I stayed a little in the shade.’ After hearing that they had come from the old cantonment and were going into the city to their homes he let them proceed. And they went on again till they reached a stone bridge by which they crossed the Goomtee and entered the principal street of Lucknow, which fortunately was not so brightly lit as before the siege, nor was it so crowded. ‘I jostled against several armed men in the street without being spoken to, and only met one guard of seven sepoys who were amusing themselves with women of pleasure.’ They threaded their way through the heart of the city to the open country on the far side. ‘I was in great spirits when we reached the green fields into which I had not been for five months, everything around us smelt sweet, and a carrot I took from the roadside was the most delicious I had ever smelt.’

The next five miles of the journey was pleasant. Then they discovered that they had lost their way and were in the Dilkoosha Park, which was occupied by the enemy. ‘I went within twenty yards of two guns to see what strength they were and returned to the guide who was in great alarm, and begged I would not distrust him because of the mistake as it was caused by his anxiety to take me away from the picquets of the enemy.’ Kavanagh reassured the man by informing him such accidents were frequent even when there was no danger to be avoided. It was now about midnight. They attempted to persuade a farmer who was watching his crop to show them the way for a short distance, but he pleaded old age and lameness. Kavanagh then commanded him to accompany them. He ran off screaming and alarmed the whole village, and the dogs made them beat a quick retreat to the canal ‘in which I fell several times owing to my shoes being wet and slippery and my feet sore. The shoes were hard and tight and had rubbed the skin off my toes, and cut into the flesh above the heels.’ Two hours afterwards they were again on the right track, two women in a village having kindly helped them to find it. They reached an advanced picquet of sepoys who also told them the way after having asked them where they had come from and where they were going. By three o’clock they reached a grove and heard a man singing. ‘I thought he was a villager; but he got alarmed on hearing us approach and astonished us by calling out a guard of sepoys all of whom asked questions. Here was a terrible moment. Kananji Lal lost heart for the first time and threw away the letter entrusted to him for Sir Colin Campbell. I kept mine safe in my turban. We satisfied the guard that we were poor men travelling to Umeenla, a village two miles this side of the Chiefs camp, to inform a friend of the death of his brother by a shot from the British entrenchment at Lucknow, and they told us the road.’

After continuing for half an hour in the direction indicated they suddenly found themselves in a swamp which they waded through for two hours up to their waists in water and through weeds. ‘I was nearly exhausted on getting out of the water having made great exertions to force our way through the weeds and to prevent the colour being washed off my face. It was nearly gone from my hands.’ Kavanagh thoroughly worn out by cold and fatigue rested for fifteen minutes despite the remonstrances of the guide. Then they again trudged forward and arrived at two picquets about three hundred yards apart seated with their heels to the fire. ‘I did not care to face them, and passed between the two flames unnoticed for they had no sentries thrown out.’ A little later they met several villagers with their families and chattels mounted on buffaloes. They said they were flying for their lives from the English. As the moonlight dimmed they stopped at a corner of a mango grove and Kavanagh, weary in body and spirit by the night’s work, lay down in spite of Kananji Lal’s pleas, to sleep for an hour. He asked his companion to go into the grove to search for a guide.

No sooner was Kavanagh left by the scout when he was startled by the challenge, “Who comes there” in a native accent. ‘We had reached a British cavalry outpost. My eyes filled with joyful tears and I shook the Sikh officer in charge of the picquet heartily by the hand.’ The old soldier sent two of his troopers to guide Kavanagh to the advanced guard. The day was coming swiftly brighter when a bedraggled individual presented himself before the tent of the Commander-in-Chief. ‘ As I approached the door an elderly gentleman with a stern face came out, and, going up to him, I asked for Sir Colin Campbell. “I am Sir Colin Campbell” was the sharp reply, “and who are you?” I pulled off my turban and opening the folds took out a short note of introduction from Sir James Outram.’

With the information brought by Mr. Kavanagh and the despatch and plan sent by Outram, the Commander-in-Chief was able to finally determine his plan of operations. Outram recommended that the advance should be by way of the Dilkushah and the Martiniare; by this route the Goomtee would protect the right flank and the force would avoid to a great extent the outskirts of the City and the narrow streets where the previous relieving force had suffered so heavily. This plan the Commander-in-Chief adopted.

By midday on 10 November, a message was sent to Sir James Outram from the Alambagh (a fortified garden nearly two miles outside the city) by semaphore on the roof of the garden-house, informing him of the safe arrival of Mr. Kavanagh, and his wife was then, for the first time, told of his escape. On the afternoon of 17 November, Mr. Kavanagh ran alone in advance of the relieving force to the nearest post of the Residency, and led over Sir James Outram, through the fire of the enemy, to Sir Colin Campbell, when the two Generals met for the first time in their lives and in the din of war, and the besieged were saved.

Sir Colin Campbell acknowledged Mr. Kavanagh’s services thus: ‘This escape at a time when the entrenchment was closely invested by a large army and communication, even through natives, was almost impossible, is, in Sir Colin Campbell’s opinion, one of the most daring feats ever attempted, and the result was most beneficial, for in the immediate subsequent advance on Lucknow of a force under the Commander-in-Chief’s directions, the thorough acquaintance with the localities possessed by Mr. Kavanagh and his knowledge of the approaches to the British position were of the greatest use; and his Excellency desires to record his obligations to this gentleman, who accompanied him throughout the operations, and was ever present to afford valuable information.’ For completing his unlikely fifteen mile endeavour, much of the success of which he attributed to the courage and intelligence of his Brahmin guide, Misqua Kananji Lal, Kavanagh was awarded the Victoria Cross.

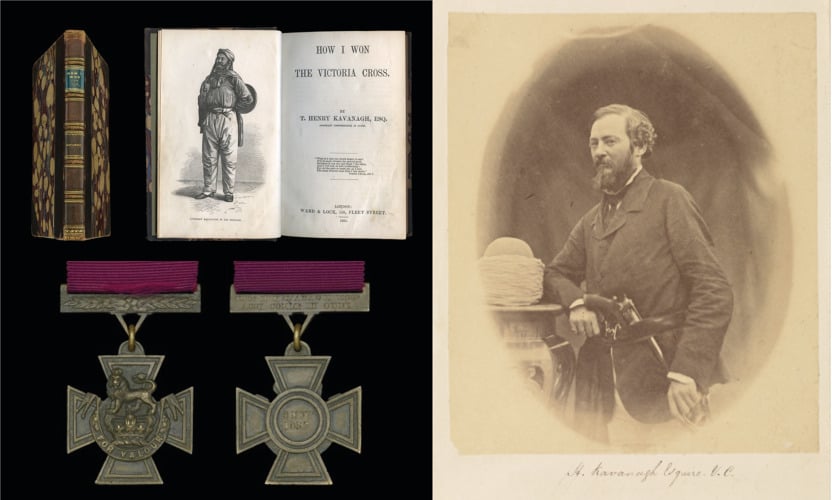

One of only five civilian V.C. recipients, he was also gazetted to the covenanted post of Assistant Commissioner of Oudh, given a reward of £2,000, and granted leave to return to England to receive his medal which Queen Victoria presented him with at a special ceremony at Windsor Castle. Nicknamed ‘Lucknow Kavanagh’, he made a tour of England and Ireland, and published (1860) his account of the siege, “How I Won the Victoria Cross”. Kavanagh then continued his career in India for some time, although it ended in some disfavour. His spendthrift ways had almost cost him his job prior to the Mutiny and he was constantly at odds with his superiors over perceived slights by the company. By 1875 he was seriously in debt again and was asked to resign. In 1882 he took ill while returning from India and died in Gibraltar at the age of 60 years. His headstone there gives his date of death as 13 November 1882.

Kavanagh’s V.C. was awarded for one of the best known episodes during the Defence of Lucknow. He was treated as something of a celebrity by Victorian society and photographs of him became popular postcard images. His portrait was famously captured by the early photographer, Felice Beato circa 1858-59; a water-colour drawing of Mr. Kavanagh in his disguise was presented to the N.W.P. and Oudh Museum at Lucknow by his son, Hope Kavanagh, Esq., District Superintendent of Allahabad; a depiction of him donning his Indian disguise was later painted by Orlando Norrie, and acquired by the National Army Museum, London, as was the oil on canvas portrait of him wearing his V.C. and Indian Mutiny medal painted by Chevalier Louis-William Desanges in 1860, one of fifty paintings by the artist between 1859 and 1862 depicting V.C. recipients or their V.C. actions.

~~~~~~~~~~~VC~~~~~~~~~~~~

Indian Mutiny Campaign Medal. No extant Indian Mutiny Medal to Kavanagh is currently known and it is not entirely clear that he was ever awarded one. His service as a volunteer at the Residency during the Siege of Lucknow and his subsequent efforts to guide Campbell’s relief force into the city would appear to have qualified him for the award of the Indian Mutiny Medal with the Defence of Lucknow and possibly also the Relief of Lucknow clasps – a highly unlikely, if not unique, combination. At the end of the siege, he also took part in the pursuit of the mutineers and in the storming of the rebel fort at Sandela, about 20 miles north-west of Lucknow, perhaps further qualifying him for the Lucknow clasp. Consistent with this, the Indian Mutiny Medal roll for Civilians held at the India Office in the British Library does contain an entry for Kavanagh showing entitlement to Relief of Lucknow and also, added later in a different hand, Defence of Lucknow and Lucknow. The entire entry is then scribbled through with a note in the margin reading ‘this is done’. It is possible, therefore, that Kavanagh was struck off the roll but the rolls for civilian claimants do contain many crossed out entries, often with additional notation such as ‘medal received’, ‘sent to India’, ‘given to relative in this country’ or reference to another roll.

Kavanagh’s diaries, from April 1859 onwards, held by the National Army Museum, contain no reference to his receipt of a campaign medal (which in any case may have been awarded earlier) but the Desanges portrait painting of Kavanagh, completed by July 1860, does depict him wearing both the V.C. and the Indian Mutiny medal with three clasps.

~~~~~~~~~~~VC~~~~~~~~~~~~

Civilian V.C.s. In order to recognise the bravery of civilian volunteers during the Indian Mutiny, an 1858 Royal Warrant extended the eligibility of the V.C. to include ‘non-military persons’ serving with the forces. Since then just five civilians have received the award (four for the Indian Mutiny and one for the Second Afghan War). Although it may still be technically possible for a civilian to win the V.C., the introduction of the G.C. in 1940 has largely rendered this question academic and since its introduction the latter award has always been preferred for civilians.

Kavanagh’s award and one of the two known crosses named to George Bell Chicken are the only civilian V.C.s not held by a museum.

Ordered chronologically, the civilian V.C.s by date of action:

- Mr Thomas Henry Kavanagh, Clerk, Bengal Uncovenanted Civil Service, 9 February 1857, Siege of Lucknow, Indian Mutiny.

- Mr Ross Lowis Mangles, Assistant Magistrate at Patna, Bengal Civil Service, 30 July 1857, Arrah, Indian Mutiny (Cross held by National Army Museum).

- Mr William Fraser McDonnell, Magistrate of Sarun, Bengal Civil Service, 30 July 1857, Arrah, Indian Mutiny (Lord Ashcroft Collection).

- Master George Bell Chicken, Indian Naval Brigade, 27 September 1858, Suhejnee, near Peroo, Bengal, Indian Mutiny (Two crosses known. One engraved with incorrect unit and date held by Lord Ashcroft Collection. Another, correctly engraved, with documentation of award to next of kin, is privately held),

- Reverend James William Adams, Chaplain to Kabul Field Force, Bengal Ecclesiastical Department, 11 December 1879, Killa Kazi, Second Afghan War (Lord Ashcroft Collection).

Courtesy of Noonans Mayfair, Sep 2022