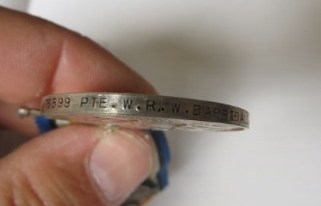

76399 – William Roy Wesley BARRIBALL

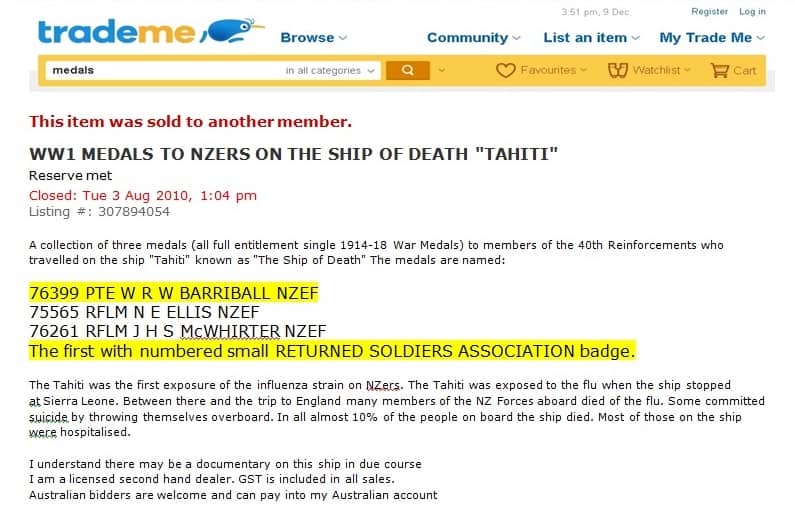

In April 2015 I received an inquiry from a former RNZAF colleague regarding his grandfather’s missing war medal. Roger related to me the story of how he had been perusing TradeMe and came upon an historical sale for a medal he recognised – his grandfathers! To Roger’s knowledge the medal had been in his mother’s possession and so was understandably gobsmacked to see the medal, a British War Medal 1914-18, had been sold on TradeMe five years beforehand in 2010.

The war medal had been advertised together with two others, also British War Medals, all three being the sole entitlement of three men who had left New Zealand on the same reinforcement draft. In addition, the medal that had belonged to Roger’s grandfather still had his pre-WW2 style RSA badge pinned to the ribbon, complete with a Red coloured “1952” clasp attached to the crown. The year clasp was an indication of the member’s financial standing in any given financial year. Having paid ones annual subscription, a receipt was issued along with a different coloured Year clasp to replace the previous year. The colour was changed each year so that RSA committee and executive members could easily identify the non-financial members, these having no right to vote in either the local Club or National RSA elections. The practice of issuing an annual Year clasp was scrapped in the 1990s when RSAs loosened their grip in dire need of customers, becoming somewhat more identifiable as commercial or chartered clubs with pretty much ‘free-for-all’ membership. The clasp on Roy Barriball’s badge ironically showed he was a financial member for the 1952-53 financial year – and was still a financial member when he died in Feb 1953.

Roger’s quest

It was four years since Roger’s widowed mother, Mrs Betty Barriball had passed away in 2011. Mrs B. had spent the last few years of her life living next door to Roger and his family in Christchurch. The last thing on Roger’s mind when she passed away was his grandfather’s medal. He had forgotten all about it until he was suddenly reminded of it when he spotted an August 2010 TradeMe page for the sale of his grandfather’s medal! Exactly how the medal had arrived in the hands of an Auckland collector/trader who had auctioned it on TradeMe, along with two other identical medals, is unknown. Since seeing this Roger had attempted to find answers to the mystery and to whom the medal(s) had been on-sold but got no assistance from any quarter.

From that time, Roger had been on a mission watching TradeMe and eBay in the hope his grandfather’s medal might re-appear one day. Roger’s father and more particularly his grandfather Roy Barriball had rarely spoken of Roy’s service and so Roger had researched his grandfather’s service fairly extensively to find out what exactly it was he had been involved with during the First World War. Once he realised the reason why his grandfather had qualified for only the one medal, its loss became of even greater concern to him. Roger made several attempts over the ensuing years to trace the medal. He had contacted TradeMe and even found out who the Auckland collector/trader who had on-sold the three medals, but neither could/would assist him. With no other avenues open to him, it was at that point Roger contacted me in April 2015 to see if I could do anything to help.

Once he had outlined they story to me and showed me the TradeMe page, I knew exactly who was involved and made some inquiries of my own – I too got zero assistance. After giving Roger some advice about tracing missing medals, the best I could offer him at the time was to list his grandfather’s medal on our Medals~LOST+MISSING page of this website, and to keep his fingers crossed. I then acquainted myself with Roy Barriball’s circumstances and those of the other two medal recipients. It was then that I too fully understood why finding his grandfather’s one and only medal meant so much to Roger, but in all honest, I had to tell him that I held out little hope of seeing any of the three medals again, let alone his grandfathers.

Roy’s story

Roger’s grandfather was 76399 Rifleman William Roy Wesley BARRIBALL. Known as Roy, he was a 31 year old Farmer from Pukeoware, near Waiuku when he was called up for war service. For his service Roy had returned home with his British War Medal, 1914-18, this being the only medal he was awarded as was the case for the two soldier’s whose medals were sold with it – 75565 RFLM Norman Elijah ELLIS (a Carrier from Wellington) and 76261 RFLM James Hugh Smith McWHIRTER (a Scotsman, Shepherd from Dannevirke). All three medals had proven to be a source of considerable interest to collectors and traders from the time the first appeared on TradeMe, given the number of ‘Watchers’ when they appeared and their sales history. This was undoubtedly due to the uniqueness of circumstances under which they were awarded, circumstances that in time had enhanced their value. The reason? – all three soldiers were survivors of the “Ship of Death.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In 1999, Roger’s mother Mrs Betty Barriball, had been widowed from her husband Keith. As a result Betty became the custodian of a British War Medal that Keith had inherited from his father, Roger’s grandfather, (WRW) Roy Barriball. Betty Barriball herself had served during WW2 with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and had received medals for her own service. It was believed by family that Betty’s medals plus others she kept from family members past, and Keith’s medal, were kept together. After Betty passed away at the age of 87 in 2007, son Roger had the task of executing his mother’s estate and during the removal of property from her home, he recalled to mind his grandfather’s medal which he looked for. Roger found his mother’s medals as she had recently had them remounted however his grandfather’s was nowhere to be found, causing him considerable concern. As the eldest and only son, Roger had anticipated his mother passing his grandfather’s medal to him when she decided the time was right. Confident his mum would never have sold a family medal, he wondered if she might have given it to someone else in the family, or had it been lost? After drawing a blank from his questions of family, Roger had resigned himself to the medal being lost forever.

You can well imagine how shocked he was at seeing this family heirloom on TradeMe, albeit for a sale that was made five years previously in 2005. Roger had attached considerable importance to this one medal for a good reason. Grandfather Roy had never spoken of his experience to Roger, or said very much to even Keith his son, for that matter. Roger being curious of Roy’s unwillingness to speak of his ‘war’ had carried out some research himself and learned of the extraordinary circumstances of which his grandfather would not speak. It was because of this, that his grandfather’s British War Medal had special significance to Roger which fuelled his determination to try and recover the medal.

Medal entitlement

Under normal circumstances most First World War soldiers (and nurses/WAACs) who spent time in the ‘war zones’ of France or Belgium had qualified for two or three campaign and service medals – 1914 Star (specified service from Aug-Nov 1914); 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18 and the Victory Medal. Soldiers overseas before 30 Dec 1915 received the 1914-15 Star; the British War Medal required overseas service but could also be awarded for those in uniform who did not enter a war zone and was most often partnered with the Victory Medal. The Victory Medal was a multi-national award agreed to by participating Allied nations at the Versailles Conference after the war in 1919 to acknowledge those personnel who had ‘entered a theatre of war’ (war zone) be it on land – Egypt, Gallipoli, France, Belgium or Germany; aboard a ship in designated threat areas, or in the air.

The qualifying criteria determined that a serving man or woman who was in a war zone before 31 December 1915 would qualify for three medals: 1914 or 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal – this trio was referred to by the Brits as “Pip, Squeak & Wilfred.” Those soldiers who entered a war zone after 31 December 1915 (post Gallipoli) would qualify for the British War Medal and Victory Medal only – this pair was the most common combination WW1 soldiers and nurses wore, and were nicknamed “Mutt and Jeff.” ** Uniformed personnel on duty who served in England only were awarded the British War Medal, 1914-18 on its own.

When Private Roy Barriball left Wellington for war service in July 1918, probably pre-occupied with what he was likely to face on the Western Front, little did he suspect that the hand of fate would intervene and deprive him not only of more than one medal, but very nearly his life! The danger he would face was equal, if not more lethal than that which he would face from the enemy’s shot and shell.

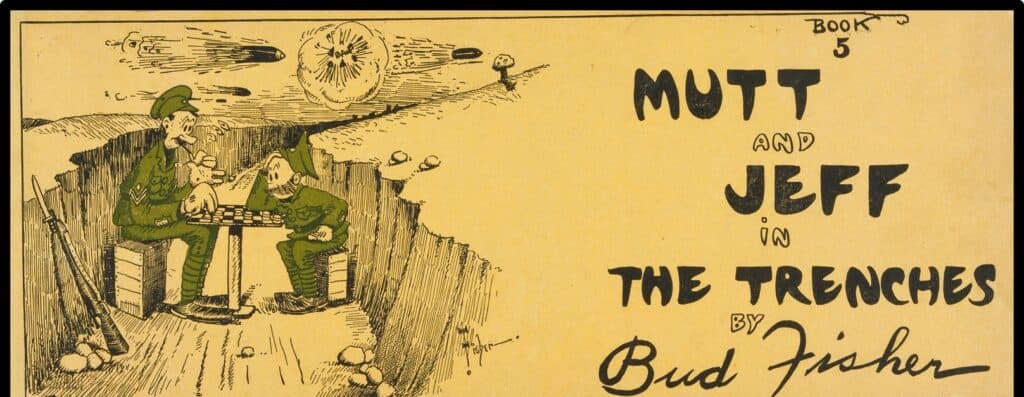

In 1907, a San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist (Harry Conway “Bud” Fisher) began drawing a daily comic strip called “Mr Mutt”. A short time later he added the diminutive “Mr Jeff”, and “Mutt and Jeff” were born. Mutt was a tall lanky man with a penchant for the horses, while Jeff looked like the down trodden, hen-pecked husband of a tyrannical house mother. Starting out as an amusing side strip in the Chronicle sporting pages, by 1915 Mutt and Jeff had become a national phenomenon in the USA, Britain and Canada. The strip ran continuously under Bud Fisher’s guidance until his death in 1954, after which it was produced by a team of illustrators and writers until “Mutt and Jeff” were eventually retired in 1982.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Barriball origins

Charles BARRIBALL (1811-1880) was an early New Zealand pioneer and settler who hailed from Cornwall. Of Cornish farming stock and a staunch Wesleyan (Methodist), Charles married Ann MARTYN of North Tamerton, Cornwall in 1836. When Charles’s brother Henry Barriball took up an offer made by the New Zealand Company to settle a new community at New Plymouth, on offer which encouraged migration of farmers and tradesmen with a promise of cheap fares and a land grant, Henry and his family emigrated from Cornwall in Feb 1842. The positive reports Charles received from Henry which talked of opportunities and the benefits of their new country, Charles was eager to follow him. One year after Henry left England, Charles and his family decided to go.

Charles and Ann Barriball with their three children – John (6), Samuel (3) and Sophia (1) embarked on the three masted barque Westminster together with 78 other migrant families. The Westminster left Plymouth on December 4th, 1842 and after making good passage to New Zealand in 128 days, the 225 passengers disembarked at Auckland in the Province of New Ulster on March 31st, 1843 after an uneventful voyage.

After re-assessing his situation on arrival, Charles decided the family would stay in Auckland rather than go on to New Plymouth, and settled his family in the vicinity of Mount Eden. Here he leased land at Eden Grove from a Methodist minister and began farming whilst waiting for a grant of land. In May 1856, a Crown grant of 156 acres at Waiuku saw the Barriballs quit the Epsom area. The land at Waiuku was virgin bush and took Charles around four years to clear and to build a home on. Here they would remain until Charles’s death in 1880. Eight months after moving to Waiuku, Charles took an option on a further 442 acres at East Waiuku, an area originally known as Waitangi, later re-named Pukeoware. This property he named “Eden Hill” which was eventually taken over by his son Ivor Barriball.

It was from these beginnings that successive generations of the staunchly Presbyterian Barriballs were born. Unafraid of hard work, all had been raised, schooled in a town they had largely built with other migrants who had arrived with them and subsequently. Land was cleared, farms were built, stock bred and crops grown all the while they were also contributing to building the institutions of commerce and governance in the fledgling Waiuku township. Leadership roles in the Wesleyan church, school board, local bodies, justice, national government, fraternal organisations and the militia were liberally represented with the contributions and achievements of Charles and Ann Barriball’s descendants.

From this background came Roger’s grandfather. William Roy Wesley Barriball (known as Roy) was born at Mt Eden in 1886 and his brother Daniel William Ivor Barriball (1891-1981), known as Ivor, at Waiuku. Roy and Ivor grew up gaining their farming education from their father William Henry Barriball while their mother Annie Segetia, nee BAYLY (1861-1941) was ably assisted by their sisters Zillah Segetia Beatrice NIXON (1887-1966) and Ada Jessie Winnifred FINLAYSON (1893-1981).

The World at War

In 1918 World War 1 was still raging in France and Belgium 2½ years after the first New Zealand contribution had landed at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. How long the war would last was anyone’s guess but what was clear was that continued need for large numbers of reinforcements – desperately. NZs casualty rate since the first days of action in the Gallipoli campaign had cut a swath through the young men of our nation and at this point in the war, their ranks had been depleted and volunteers reduced to a trickle. The pressure from the Imperial military authorities in Britain to provide greater numbers of reinforcements together with the loss of young and fit fighters to alarming casualty statistics meant that conscription and acceptable standards of fitness needed to be adjusted to create a larger pool of replacement soldiers (volunteers and conscripts). To this extent, older men including those who were married (and with families), those who had initially been rejected as unfit, or for some other reason, were now being re-considered to make up the numbers required since they now constituted the only remaining resource.

The regulations for the medical examination of recruits were similar to those prescribed for admission to the New Zealand Permanent Staff, and the age limit for overseas service set from 20 to 40 years. From September 1917, 19 year old volunteers were accepted for overseas service provided they had a parent or guardian’s permission. The upper age limit was also raised from 40 to 44 years.

Infantry training

76399 Rifleman William Roy Wesley Barriball was enlisted at Trentham with the 40th Reinforcements on 14 Feb 1918, five weeks short of his 32nd birthday. The 40th Reinforcements comprised 800 men who were destined to fill casualty vacancies in the battalions of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade and both NZ Infantry Brigades. Rflm. Barriball was initially assigned to E Company for training and administrative purposes. The first order of the day for the new arrivals was the completion of enlistment procedures including Attestation (contracted for the duration of the war), the issue of Pay Books, completing Allotment authorities, completion of a Will, and the issue of a few basic items of (contracted for the duration of the war) equipment required whilst at Trentham (KFS = knife, fork and spoon; uniform, boots, laundry bag, shaving kit, etc) until the transferred to Featherston. Hut allocation, groupings into sections they would train with, were just some of the first week’s routine. Fire Drills, parading to raise and lower the flag at dawn and dusk were all part of their induction into military life. Once the administration was completed and all ranks had been accounted for, the reinforcement draft was dispatched to the reinforcement training camp at Featherston in the Wairarapa.

In January 1916, New Zealand’s infantry was divided into three brigades. The Rifle Brigade was officially known as the 3rd New Zealand (Rifles) Brigade for the rest of the war (‘New Zealand Rifle Brigade’ also served as a regimental list or posting for its soldiers). It shifted to the Western Front in April 1916 and spent the rest of the war there.

Featherson Camp

Here the men underwent further medical and dental inspections. Prior to each man’s enlistment he was required to undertake a basic medical screening from an approved medical specialist near their home town. Once at Featherston, all recruits were subject to a final assessment of medical fitness for active service. This was done by the permanent Army Medical staff where checks were conducted for illness, injuries and ailments since their initial medical screening, to ensure the soldiers could stand the rigours of the training they were about to undertake and were in fact medically fit to fight.

To this point the men had been in the hands of approved civilian medical specialists and trainers (mostly in the Territorial Force) which included a wide range of Army approved GPs, but some of who were less than diligent by allowing some deficiencies to pass. In particular, determined volunteers such as those who had possibly cashed themselves up, sold their property, and/or left their jobs in order to serve, were often passed fit in an act of compassion rather than denying the opportunity to serve. Knowing some had a border-line pre-existing conditions or injury was overlooked in what can only be described as an act of compassion. On the battle field however, this could cause unexpected problems that could have been avoided. Conversely, the more hard-lined medicos who had dealt with their fair share of conscript ‘shirkers’ sometimes felt less than sympathetic toward these and passed as fit a number with non-serious fitness and alleged medical or physical issues, as being fit for service.

It was also a well known fact that during the previous years of recruitment, many a volunteers had attempted (some successfully) to conceal all manner of pre-existing conditions or deficiencies if they thought exposing these would threaten their chances of serving overseas. To a lesser extent were those who ‘malingered’ or feigned a condition or ailment in order to avoid being sent overseas. The NZ Army Medical Corps staff at Featherston Camp had seen it all before and were well versed in spotting both. Very few escaped their scrutiny – eyesight, hearing, lungs, heart, joints, evidence of hernia, and dental fitness were all again checked.

Featherston Camp was the great leveller – the fitness of the men to serve in a Rifle Brigade and their training was in the hands of the Army’s Permanent Staff, combatant and medical, of the Reinforcement Camps.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It was during the medical check at Featherston that Private Barriball’s deployment to England, his trip of a lifetime, came to a shuddering halt. The men were classified according to their medical fitness in accordance with the chart below:

|

A |

Fit for active service beyond the seas |

|

B1 |

Fit for active service beyond the seas after operation in Camp or Public Hospital |

|

B2 |

Fit for active service beyond the seas after recovery at home |

|

C1 |

Likely to become fit for active service after special training |

|

C2 |

Unfit for active service beyond the seas but for service of some nature in New Zealand |

|

D |

Wholly unfit for any service whatever |

Whilst Rflm. Barriball had been passed as medically fit for service – eyesight, hearing, teeth etc., his physical fitness fell short of the required standard for active service. On the up-side, he was considered likely to be become fit with work, and so in Apr 1918 was transferred to D Company for remedial training in an attempt to bring him up to the required level. Rflm. Barriball and others who required the training were put on an intensive training regime as they had only eight weeks to make the grade before they were due to embark.

Rflm. Barriball passed the fitness requirements and was re-classified: “A – Fit for service beyond the seas.” He completed the basic training at Featherston Camp and joined the infamous three day route march from Featherston Camp to Trentaham Camp via the Rimutaka Hill Road.

During World War 1 over 30,000 New Zealand soldiers marched between military camps at Trentham, Upper Hutt and Featherston via the Rimutaka Hill Road, in a three-day trek of 27 miles (43.5 km). There were 23 marches of 500 to 1800 men between September 1915 and April 1918, at the end of their training as reinforcements for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. On completion, the 40th was packed off to their home towns in June 1918 on pre-embarkation leave before their July departure to England.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

England bound – HMNZT 107 Tahiti

RMS Tahiti was a 7,585 ton passenger liner that was operated by the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand. Built in 1904 on Clydebank by the shipbuilders Alexander Stephen and Sons, she was originally named RMS Port Kingston. Purchased by the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand in 1911, the Port Kingston was re-named RMS Tahiti. With the looming commitment of New Zealand forces to the war in Europe, Tahiti was loaned to the NZ Military Forces to move the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to and from England. Stripped of her luxuries and re-fitted for service as a troop carrier, Tahiti was re-designated His Majesty’s New Zealand Transport (HMNZT) Tahiti. Each of the troop ships was assigned a temporary number that designated the voyage number they were undertaking. HMNZT No.4 Tahiti formed part of the initial 1914 convoy which that transported the first NZ soldiers destined for Plymouth in England. As we now know, the convoy was diverted to Egypt after the Ottoman’s entered the war which became a precursor to the ANZAC the landings at Gallipoli. In 1915 the Tahiti brought the first contingent of wounded from the Gallipoli Campaign back to Wellington.

On 10 July 1918, HMNZT 107 cast off from the Wellington wharf around 1400 hours and eased into the harbour where she sat before clearing the Wellington Heads at around 1700 hours. The Tahiti left New Zealand carrying the 40th Reinforcements, a group of NZ Rifle Brigade replacements under command of Lieut. Colonel R. C. Allen. Sailing with the four companies (A, B, C & D) of Riflemen was an Artillery company and a Specialist company (Engineers, Signalmen, Machine-gunners) which totalled 1172 soldiers. A support staff and the ship’s crew accounted for another 100 personnel, the ship’s compliment totalling 1217 on board.

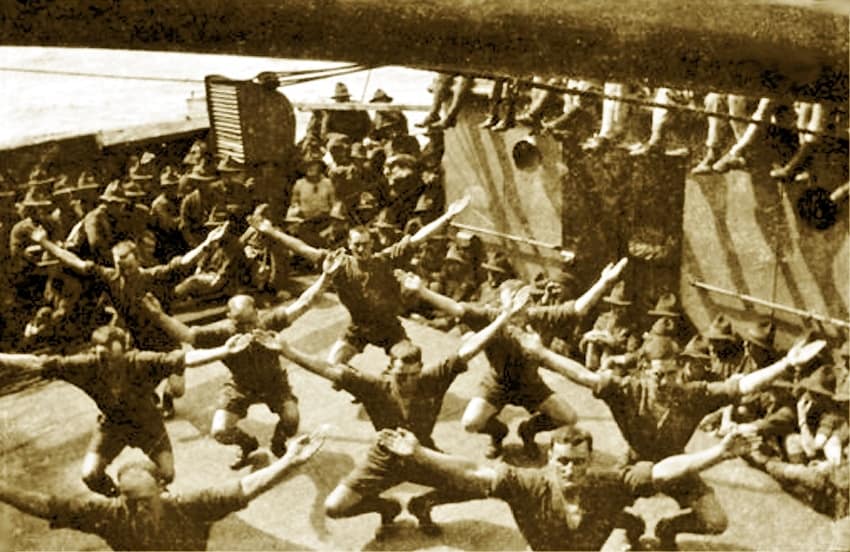

The ship made a course for Western Australia and her first stop at Freemantle prior to rendezvousing with the convoy escort located off the coast of West Africa. Life on the Tahiti was relaxed but governed by a relatively strict routine, no different to the numerous voyages of troopships that had gone before carrying thousands of New Zealanders and Australian service personnel to Egypt and England. A new ‘sailors’ soon found their sea-legs and settled their queasy stomachs to a manageable state. The soldiers settled into their sea-board life which would be their home for the next 62 days (approx 9 weeks) before they reached Plymouth, weather and the presence of enemy submarines, surface ships or mines notwithstanding. Ship-board life was a routine that combined inspections, fitness training, sports activities, eating and sleeping. The obligatory ‘dhobi’ (clothes washing) was each man’s responsibility as was the maintenance of his rifle and personal equipment in clean and good working order. Card schools and reading were the two most popular pastimes, when the military band on-board was not entertaining.

Pandemic

The voyage to southern Africa was uneventful and once around the horn of Africa, Tahiti proceeded north along the west coast to Freetown where she met her convoy group on 22 August. On arrival at Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, the ship’s officers received reports of disease and illness ashore which immediately resulted in all ships in the convoy being quarantined at the port however this was not completely enforced. While those on board Tahiti were barred from leaving the ship at anchor in the bay, this did not prevent local workers from resupplying the ship as she waited. Since influenza can be infectious for a day before symptoms appear, these workers could have felt fine and still unknowingly spread the disease.

Spanish Flu

In mid 1918, a strain of highly infectious N1H1 influenza virus had been widely reported infecting large numbers of Spanish citizens, the King of Spain being one of the first victims. Once out of Spain the virus had taken off and spread across Europe like wild fire. Due to the prevailing media blackout conditions, word of the infection travelled much more slowly than the speed at which the virus spread. The so-called ‘Spanish Flu’ wasn’t any ordinary winter sniffle or head cold. Those who were fine and healthy at breakfast could be dead by tea-time. Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of fatigue, fever and headache, some victims would rapidly develop pneumonia and start turning blue, signalling a shortage of oxygen. They would then struggle for air until they suffocated to death. Initially it was found that recovery was quick and doctors had called it the ‘three-day flu’ but with subsequent waves of the virus, it soon proved to be much more devastating, and fatal, which would leave millions dead in its wake.

For the soldiers on the Western front, or back in England recuperating, on leave, and those arriving in fresh reinforcement drafts at the NZEF’s Codford Camp in Wiltshire, there was also no escape. Those who had been in the field for a considerable period of time, months and years in some cases, were likely to be somewhat more debilitated by their months and years in the field. The rough living conditions implicit in trench warfare, battle fatigue, injuries, wounds, inadequate food quality/quantity and mental states, all contributed to large numbers of generally debilitated soldiers whose weakened immune systems had limited ability to fight off an attack of the Spanish Flu. For many, catching the virus would be a death sentence.

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians alike were stricken as the flu swept across the northern hemisphere. It would be only a matter of time before New Zealand and Australia fell victim to the virus’s reach. In the meantime, the body count of NZ soldiers on the Western Front and in the surrounding countries, together with those killed and wounded on the battlefield, sky-rocketed the Kiwi casualty statistics. The virus peaked towards the end of the war in late October 1918 however, as the war ground to a halt on 11 November 1918, soldiers returning from France who had been exposed to the virus, carried it home with them which set up a Second Wave of infection in their home countries. In Britain alone the flu killed around 250,000. In the NZEF, in excess of 228, 000

New Zealand had, at this time, not been significantly affected by either the First or Second waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic and thus those aboard Tahiti had no exposure and, no resistance to the virus. The troops aboard the Tahiti, some of the last replacements sent to the Western Front from New Zealand however were to become some of the first New Zealanders known to suffer from the infection. As we have also seen with the COVID-19 pandemic that is sweeping the world in 2020, the virus evolves in waves. At the time of writing, a Second Wave is sweeping through the USA and UK with devastating effect. And so to it was in 1918. Within two months of New Zealand being infected, the death toll accounted for almost 9000 civilians and soldiers. The Maori population were more susceptible and accounted for a much higher morbidity rate than European New Zealanders.

Onward to England

HMNZT 107 Tahiti departed Freetown for England in an escorted convoy four days later on the 26th August, the day the first soldiers began reporting to the ship’s hospital suffering with flu symptoms. By the following morning more than 60 men reported to the Sick Parade with flu symptoms while another 24 were hospitalised. It was the first occasion New Zealanders had exposure to the H1N1 influenza virus strain.

Given the hospital’s capacity topped out at 36 persons, the majority of patients had to tough it outside in deck areas marked off for the purpose. The biggest problem on the ship was an inability to isolate the infected as the men’s quarters were confined to the bow of the ship meaning it was cramped with men having to sleep in rows, cheek by jowl (“packed in like sardines” as one soldier described it). The worst day for infections was the third day (29th) out of Freetown when more than 800 soldiers and crew, including both of the ship’s doctors, were hospitalised onboard.

Note: In a subsequent investigation which looked into how the virus might have been introduced to HMNZT 107, it was thought to have been brought to Freetown by the HMS Mantua, an armed cruiser which had developed influenza onboard two days after leaving an infected London on 1st August 1918. Unfortunately, this was the vessel which hosted a meeting of all the wireless operators and captains from the ships in the convoy including Tahiti’s captain. Having attended the meeting aboard a still infected Mantua, the captain and the wireless man very likely brought the infection back to the Tahiti.

Extracts from: “Influenza on the SS Tahiti” by Ryan McLane – Historian

Ironically, as Tahiti sailed towards England she was entering the eye of an even bigger storm from which there was no planned escape. Britain at this time was fast falling victim to the virus which had within a few months overwhelmed both military and civil medical facilities in that country.

As the voyage proceeded, eventually 1100 (90%) of the 1217 personnel on board became ill. The burials at sea began almost immediately. On 2nd September alone there were six such burials and by the next day, 33 deaths had been recorded, including a delirious man who jumped overboard. The men (and one woman) who died were generally healthy and between 25-34 years of age. These were young people who had been healthy when the Tahiti reached Sierra Leone, and had succumbed to influenza in the fortnight’s voyage to Britain.

The “Ship of Death” as Tahiti became known, finally reached Plymouth on 10 September 1918, just four weeks before the Armistice was signed ending hostilities between the Axis and allied powers. The situation onboard was so severe that special trains were sent to Plymouth to transport the ill to influenza hospitals, with the majority of personnel on the ship being hospitalised.

The death toll onboard accounted for 68 members of the NZ Military Forces. To this total would be added another 9 soldiers who died in hospitals ashore.

By mid-October 1918, six weeks after HMNZT 70 had arrived at Plymouth, of the 1017 troops that were on board only 260 were fit for deployment. Seven percent of those who started the voyage from New Zealand had died from the influenza, making the outbreak on the Tahiti several times more severe than that which eventually struck New Zealand itself.

The General Officer Commanding NZEF in Britain was not without a good degree of empathy for the plight of the Tahiti’s soldiers and promised them all a week’s leave and a free rail pass anywhere, once the danger of infection had passed. The General’s promise was honoured four weeks later after the 40th Reinforcements had arrived at Brocton Camp.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Arrival at Plymouth

Rflm. Barriball was admitted to No.3 NZ General Hospital at Codford Camp on 11 Sept 1918. Codford was a subsidiary New Zealand facility used to house reinforcements and to convalesce recovering wounded, injured or sick NZEF soldiers. Sling Camp at Bulford, some 120 km to the south on the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire was the New Zealand Base Depot in England through which all NZ troop arrivals and departures (to France or NZ) passed. Brocton Camp manned by a permanent NZ military staff, the soldiers arriving at Sling were firstly accounted for and housed, then allocated to units and sections, equipped, prepared for combat, underwent battlefield rehearsals, and where appropriate, farmed out for specialist training. The infantry trained on the Salisbury Plain and so remained at Sling or Codford camps. Separate depots had also been set up for NZ and Australian troops in existing British Army facilities scattered around England for the purposes of Artillery, Field Engineering, Signals and Machine-gun training.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rflm. Barriball’s infection with the Spanish Flu was confirmed on the 15th however he was one of the fortunate few whose attack was not as severe as it might have been and so was within four days was removed from the hospital’s Infectious List on the 19th. But, he was not ‘out of the woods’ just yet and remained in hospital with the lingering effects of the flu. On November 4th he was discharged from Codford and returned to Sling Camp. With the Armistice just seven days away, the fit members of the 40th were gainfully employed making preparations to receive troops and equipment from the France at Sling Camp, and assist with the demobilisation processing preparations which would follow. All was going well for Rflm. Barriball who although felt weak, was able to work – that is, until April 1919. Rflm. Barriball was again hospitalised not with the affects of the Second Wave of the Flu that swept Britain but with Mumps! A further three weeks in hospital was ordered before he was fit enough to be discharged back to duty at Sling Camp and prepare for his own repatriation to NZ.

With the majority of his demobilisation completed at Sling and Torquay on the Devon Coast (the NZ Repatriation Depot, Rflm. Roy Barriball embarked the SS Ruahine on 19 May 1919 and left England for good. Ruahine arrived in Auckland five weeks later to disembark upper North Island resident troops before sailing on to Wellington and Christchurch. All troops received a Free Rail Pass to their home town and an immediate period of leave (about three weeks) to spend time with their families. Follow up action such as hospitalisation, on-going medical appointments to monitor recovery, and rehabilitation had to be completed before a soldier was discharged from the NZEF.

Following his final medical clearance, Rflm. Roy Barriball was discharged from the NZEF on 5 August 1919, categorised as being “no longer fit (for war service) on account of illness contracted (Influenza) while on active service.” The effect the virus had on lungs in particular had severely diminished their capacity. As a result soldiers discharged under these circumstances were not liable for Reserve service and would not be re-called to duty in the event the war re-ignited hostilities in Europe. It was also ironic that Roy had started his military service with a sub-par fitness grading that necessitated remedial work before he could deploy, and now, he was to be discharged as being no longer fit for any further service, however on this occasion it had been for a very valid reason.

Roy Barriball and the majority of the men of the 40th Reinforcement draft who had been struck down by the Flu, had dodged a bullet on the ‘Ship of Death’ – but only just. Sadly, 75 of their number did not.

Awards: British War Medal, 1914-18 and the Silver War Badge for Services Rendered

Service Overseas: 364 days

Total NZEF service: 1 year 173 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

After the war, Roy returned to the family farm at Waiuku, to his father Henry, brother Ivor, mother and sisters. After William Henry Barriball (73) died in 1923 (the result of a fall from his cart which broke his neck), Roy had by then mustered the energy to return to work with brother Ivor to pretty much picked up where he left off. Within 12 months of his return, Roy (34) had married Waiuku born Edith Maud HILL (1892-1970) in June 1920. A daughter Phyllis Maud SOWRY (1921-2012) and son, Keith Roy Barriball (1922-1999) completed their family. For the next 20 or so years Roy and his family worked and developed the Pukeoware farm however his post WW1 existence was plagued with medical issues that recurred as a result of his exposure to the Spanish Flu. His health was permanently affected and his ability to drive himself as the once stocky, well built young man he had been pre-WW1, all but faded away.

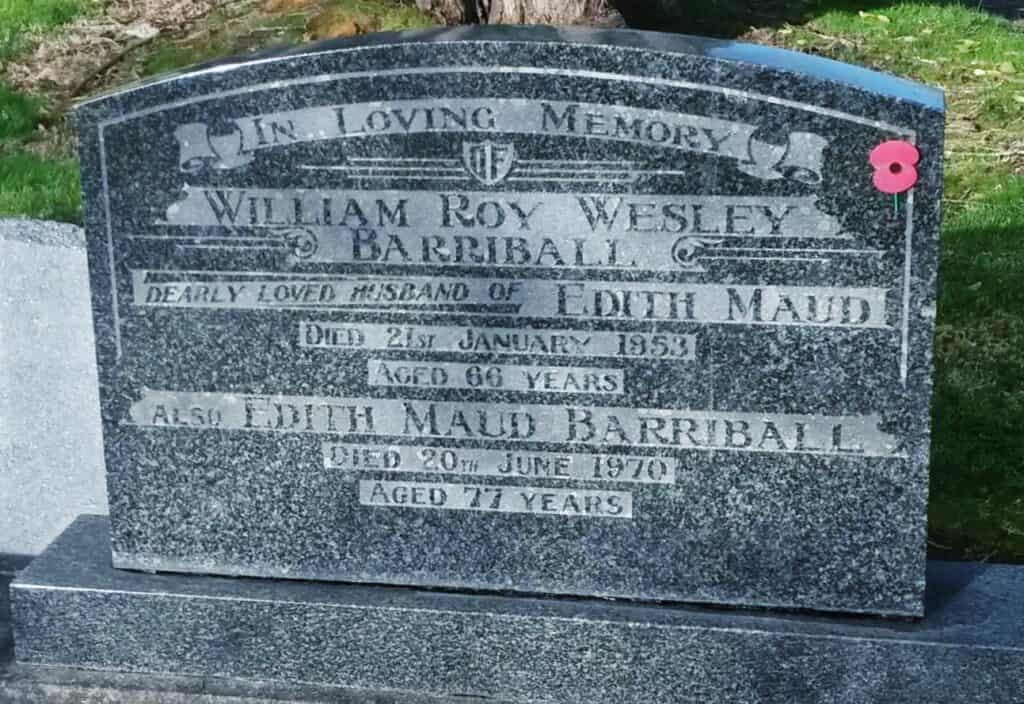

It was not unsurprising that as a survivor of the “The Death Ship” Tahiti, 76413 Rifleman William Roy Wesley Barriball died at Papakura on 21 January 1953, just two months short of his 67th birthday. This was a relatively young age for a man once muscular and physically fit being a product of clearing and farming the land around Waiuku, however, as Roger confirmed, his father had become a shadow of his former self. Since his return from England, his health had diminished and breathing problems plagued him for the rest of his days. The Spanish Flu had taken its long term toll not only on Roy but also on the numerous others who had survived that fateful voyage to England on the Tahiti during Oct-Nov 1918.

Roy Barriball was buried in the Waiuku Cemetery, to be later joined by his wife Edith in June 1970. Here they lie among their numerous Barriball ancestors, and the many other early settler families with whom they toiled to build the early town of Waiuku.

It is also noteworthy that the two soldiers named on the other two British War Medals that were sold with Roy Barriball’s medal, also led shortened lives. Rflm. Norman Ellis died in Wellington at the age of 59 in 1951, and the Scotsman, Rflm. Jock McWhirter who returned to his native Edinburgh, was 61 when he died in 1952.

~ Lest We Forget ~

Note: In writing this post I was given to recall the loss of my own uncle, also a NZ Rifle Brigade Reinforcement and who fell victim to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. 79994 Rifleman William Henry Martyn SEED, known as ‘Martyn’, was a Farmer from Southbrook, Rangiora who was enlisted with the 42nd Reinforcements on 24 July 1917. Destined for the 3rd NZ Rifle Brigade, the 42nd was the penultimate NZEF reinforcement draft to leave New Zealand. Rflm. Seed embarked on HMNZT 109 Tofua at Wellington on the 1st August 1918 which sailed for London the following day. On arrival he marched in to the 5th Reserve Battalion at Brocton Camp on 4th October. After just 27 days in England he was admitted to the Cannock Chase Military Hospital on the 31st October with Pneumonia – five days later Martyn Seed was dead! Rflm. Seed had barely adjusted to his new surroundings in England before the life of this 23 year old son of the Seed family, was over. Rflm. William Henry Martyn Seed was buried in the Cannock Chase War Cemetery. His father John “Jack” Seed unfortunately had not lived long enough to be able to comfort his wife Melinda (“Minnie”) after this tragedy as he too had been the victim of an unexpected tragedy. Jack Seed (37) was returning to Southbrook via Wellington on 12 February 1909 after visiting his flax mills in Nelson, a passenger on the S.S. “Penguin.” The ship struck a submerged rock in poor weather near the Wellington Heads, taking Jack Seed and 74 other souls down with her.

The final NZEF Reinforcement draft to leave New Zealand, the 43rd, departed Wellington on 3rd October 1918.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‘Death Ship’ aftermath

After the war, a Court of Inquiry was held to review the circumstances of the illness on HMNZT 107 Tahiti. It found the following factors had contributed:

- Overcrowding had been an issue which troops aboard had complained about since leaving New Zealand.

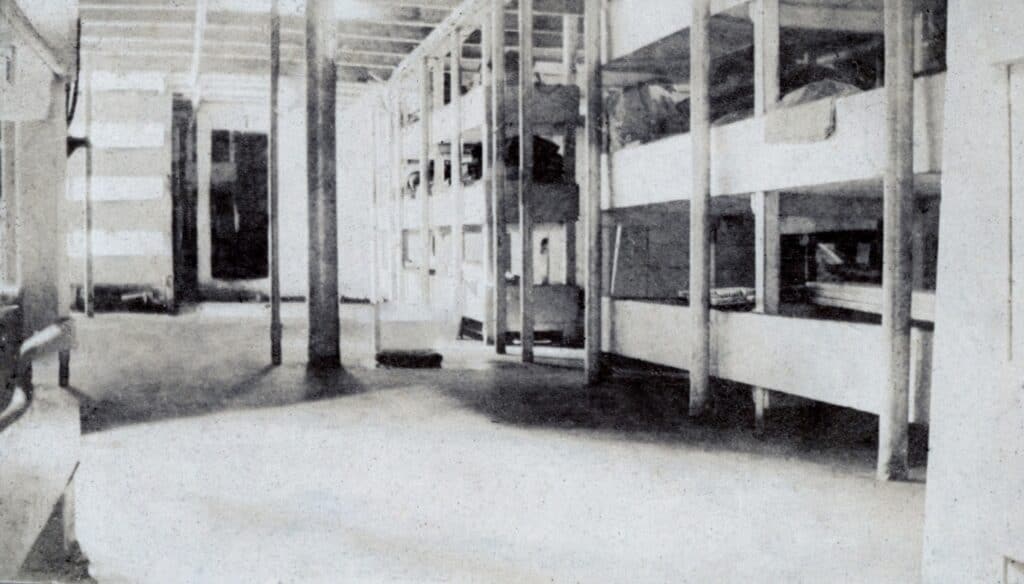

- The vessel had originally been built to hold 650 passengers and crew, but in August 1918 it held nearly twice that number. While this was not unusual for troopships in the First World War, the combination of close quarters and poor ventilation were prefect for transmitting airborne diseases such as influenza. This was also reflected in more severe infection in those sleeping in rooms with bunks rather than hammocks, as ventilation was worse in bunk rooms.

- The Tahiti’s medical staff and facilities were quickly overwhelmed by the number of cases of influenza, and as elsewhere, the trained medical professionals were generally infected quite early in the outbreak.

- As the numbers of ill rapidly outgrew the available hospital beds onboard, their isolation from those not yet infected became impossible.

The hallmark of the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic was that it had disproportionately killed those between the ages of 20 and 40, unlike previous pandemics which had had the greatest impact on the very young and the elderly. The outbreak on the Tahiti was considered by experts to be one of the worst worldwide for the 1918/19 pandemic in terms of both morbidity and mortality. The military personnel aboard Tahiti experienced a cumulative incidence of pandemic influenza of around 90%, with an overall mortality rate of 68.9 per 1,000 – or 7% of those onboard.

The Spanish Influenza pandemic infected 500 million people worldwide, and killed between 50 and 100 million, which was 3% to 5% of the world’s population at that time.

Sources: Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal: “Pandemic Influenza Outbreak on a Troop Ship: Diary of a Soldier in 1918” by Jennifer A. Summers

NZ History online & ww100.govt.nz

“Pandemic” by Ryan McLane (Historian) – https://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/otago023015.pdf

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

An unexpected find

With the foregoing background, I could fully empathise with Roger’s desire to try and find his grandfather’s medal but frankly, I didn’t hold out much hope unless it was offered up for sale by whomever had bought it from TradeMe in 2010.

Four weeks ago I was ‘cruising’ the internet looking at various medal trading sites. Whilst scrolling through the pages of a site operated from France, to my very great surprise there was a photograph of Pte. W.R.W. Barriball’s medal, AND it still had his RSA membership badge attached complete with the 1952 Red coloured Year tab fixed to the crown. Knowing Roger would not hesitate to recover the medal, I immediately contacted the trader requesting he HOLD the medal until I had contacted the family concerned. Roger was ecstatic at this completely unexpected development and did not hesitate to make contact with the trader.

I am pleased to say the medal was back in New Zealand within a fortnight and is now securely in Roger’s possession. The memory of his grandfather Roy’s near death experience will never be far from his mind on the occasions he wears the medal to honour his grandfather’s service, and survival on the ‘Ship of Death’ – HMNZT 107 Tahiti.

The reunited medal tally is now 353.

Footnote: Fate of the RMS Tahiti

RMS Tahiti was returned to passenger service after the war. On 12 August 1930 Tahiti, carrying 103 passengers, 149 crew members, and 500 tons of general cargo, left Wellington to continue a voyage from Sydney to San Francisco. She was about 480 nautical miles (890 km) southwest of Rarotonga on 15 August 1930 when her starboard propeller shaft broke, opening a large hole in her stern and causing rapid flooding. Her wireless operator transmitted a distress call, launched distress signal rockets, prepared the passengers for the possibility of abandoning ship, and fought the flooding in an effort to save the ship.

At 9:30 a.m. on 17 August, Tahiti‘s passengers and some of her crew abandoned ship, with all lifeboats away in 13 minutes. Some of her crew remained aboard in order to continue efforts to slow the flooding. Members of Tahiti‘s crew, aided by a boat from the Norwegian steamship Penybryn which had arrived to assist, then returned to Tahiti in Tahiti‘s boats and began to try to save the first class mails and luggage from the sinking ship. By 1:35 p.m. on 17 August, Tahiti was settling rapidly, and it became too dangerous for her crew to remain aboard. They abandoned ship, having saved the ship’s papers and bullion. Tahiti sank, without loss of life, at 4:42 p.m. on 17 August 1930.