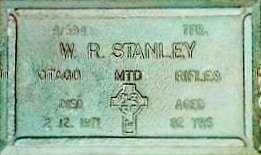

9/594 ~ WILLIAM ROBERT STANLEY

A medal posted on our Medals~FOUND page has resulted in another successful claim and return to the descendant family of a Dunedin born First World War soldier, Rifleman William Robert Stanley.

Staffordshire to Dunedin

Robert STANLEY (1809-1876), an Agricultural Labourer and Alice ARBLASTER (1813-1844) married in 1835 and lived at Stowe in Hixon, Stafford in the county of Staffordshire. Robert rented 4.75 acres of farming land that he and Alice worked growing vegetables, running a few sheep and a house cow while raising a family of 10 children, starting in 1836 with Ann, John, Mary, Jane, James, Eliza, William, Elizabeth, Robert and last born was George in 1856.

Robert Shacklock Stanley (1852-1912) was Robert and Alice’s ninth of the ten Stanley children. Robert (jnr) born in 1852 at Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire was raised at Stowe in Hixon, becoming a Wheelwright. In the year following his widower father Robert’s death in 1876, Robert (25) decided to take advantage of the New Zealand Company’s offer for cheap passage to New Zealand for English families with farming and trade skills who were wanted to populate and grow new towns such as New Plymouth, Christchurch and Dunedin. Farmers were offered land options on arrival to start a farm and tradesmen had no difficulty in establishing their business virtually anywhere they chose. After Robert S. Stanley arrived and got the lay of the land, he made his way to Westland where he worked in a timber mill, his occupation officially – Saw Miller (hand-saw that is).

Robert’s future wife, Sarah Ann OSBORNE (1855-1901) was a native of Rainham, Essex in the county of Kent. She was a 22 year old Machinist when she had emigrated from Glasgow, Scotland with her widowed mother Mary and 24 year old sister Charlotte Mary (Housemaid), her step-father (CALLICK) and two teenage step-siblings. Their ship, the Marlborough was still in the shipyards when the Osbornes and Callicks were planning their move to NZ. Marlborough was launched at Glasgow in June 1876, the sister ship of the Dunedin and the second such ship to be fitted with refrigeration to carry a cargo of frozen meat. The Marlborough had been fitted out in the three months since launch and was ready for its maiden voyage in October. The voyage would also be the maiden for the ship’s skipper, Captain Anderson. Marlborough cast off from the London Docks on 8 Oct 1876 and set sail for Capetown, Fremantle, Adelaide, Melbourne, arriving at Port Chalmers on 20 Jan 1877 after a fast passage of 81 days (usually 90-100 days).

Robert S. Stanley was a 26 year old Tally Clerk for the NZ Shipping Company when he and 24 year old Sarah A. Osborne married at the Dunedin Registry Office on 18 July 1879. The couple started their married life together in a Josephine Street cottage at Caversham where their five children were born – Bernard Osborne (1880-1943), Percival Alfred (1881-1956), Ernest Frank (1884-1948), Alice Mary (1888-1960) and finally William Robert “Bill” Stanley in 1889.

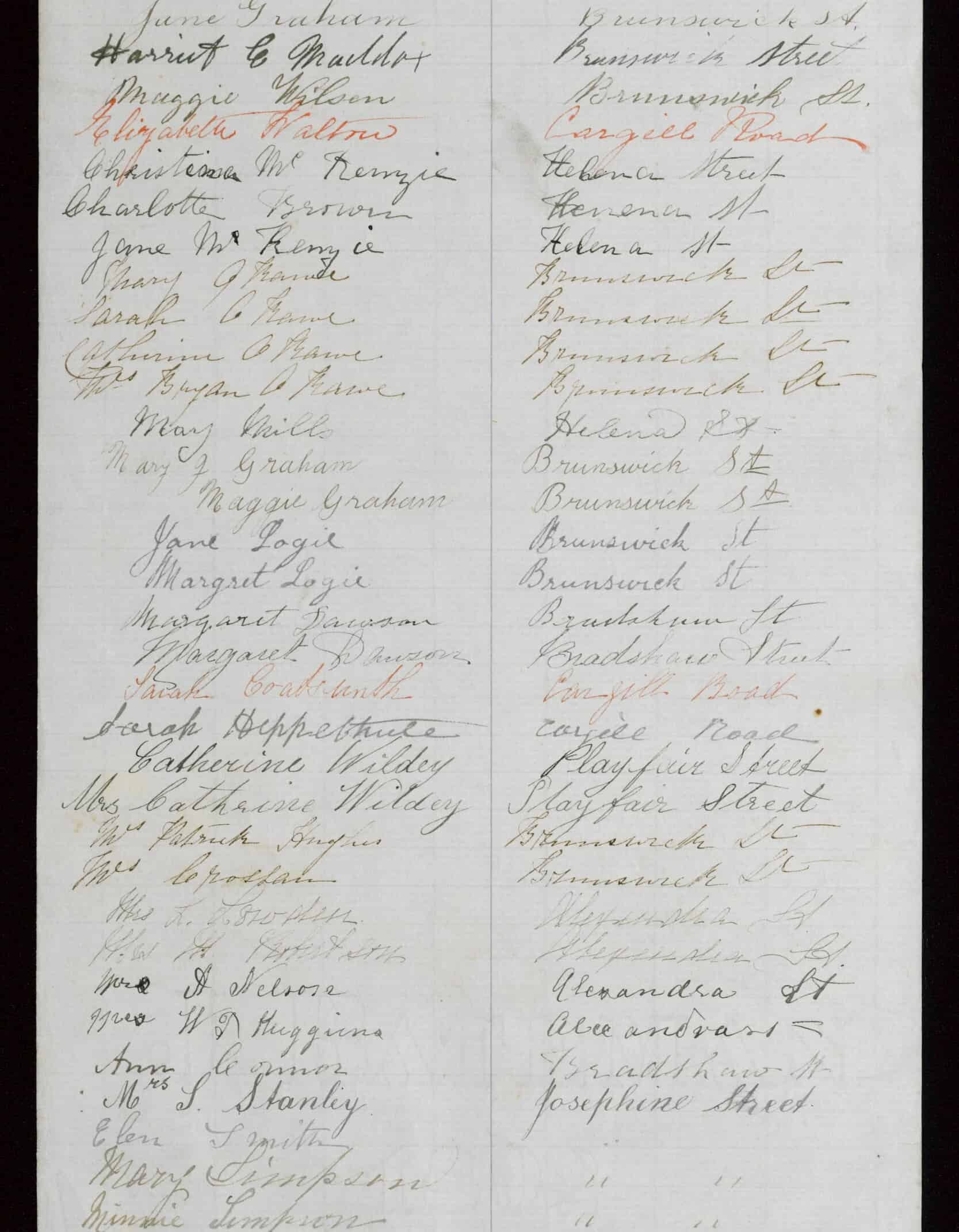

Women’s suffrage in New Zealand at this time, whilst a highly contentious proposition which was fiercely resisted on many fronts and none more so than in very Scottish influenced Dunedin at this time, never the less support for the cause from southern women was huge, and from a good number of males too. Sarah Stanley became an enthusiastic supporter of the suffrage movement, adding her name to the national petition as did her sister Charlotte BROWN who lived nearby in Helena Street, overlooking what is now Bathgate Park. Persistence by this worldwide movement to gain the vote for women was championed by English woman Emmeline Pankhurst and her sisters, while in New Zealand Mrs Kate Sheppard was the movement’s champion. “Votes For Woman“, the catch-cry of suffragettes reached its zenith in the late 1880s. The suffragette’s agitation and lobbying eventually paid off when a Parliamentary Petition for the universal suffrage of the women in New Zealand was passed into law in Sep 1893, the first country to do so.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When Bill Stanley’s mother Sarah Ann Stanley, 46, died on 4 Dec 1901, he was just two years old. Bill, his sister Alice and their father Robert went to live with Sarah’s sister Charlotte in Helena Street. Bill grew up in Caversham and achieved an education to high school standard. Brothers Bernard, Percy and Ernest all had jobs as Store-men and in due course accommodation of their own. When Bernard bought a house at 24 Fitzroy Street, still within the Caversham suburb, young Bill, Alice and their father Robert went to live with him. Bernard married Mabel NEE in 1910 and joined the largely male household at Fitzroy Street.

Bill started work as a “Carter’s Nipper”, a young labourer who assisted the driver to loaded and unload goods from horse drawn drays or carts, until he was old enough to ‘drive’ a horse drawn vehicle on his own. Once he had become a licensed Carter in his own right, Bill went to work for the Dunedin-based New Zealand Express Company. A goods transportation business, NZ Express was founded in 1867 at Dunedin and by 1920 had eleven offices in cities and towns around New Zealand. In 1908 the Dunedin head office building of the NZ Express Company building was built at No.7 Bond Street and was considered to be NZ’s first ‘skyscraper’, all seven stories of it. Apart from NZ Express, two of the long term tenants were the Dunedin Stock Exchange and the publisher and book sellers, A. H. Reed.

Answering the King’s ‘Call to Arms’

The call for volunteers to enlist in the NZEF for overseas service was met with a flood of eager and patriotic volunteers, keen to fight for their King and country. Few had any idea what they were in for. Having spent time with ‘B’ Battery of the NZ Garrison Artillery Volunteers, the territorial volunteer unit that manned the coastal artillery batteries around NZ, Bill Stanley was among the first to heed the call – he signed up to join the Otago Mounted Rifles.

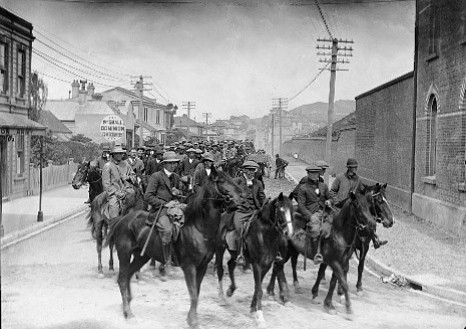

9/594 Trooper William Robert Stanley enlisted on 31 Aug 1914 with the Otago Mounted Rifle Regiment (OMR). The OMR was formed from units of the Territorial Forces consisting of the 5th Mounted Rifles (Otago Hussars), the 7th (Southland) Mounted Rifles and the 12th (Otago) Mounted Rifles, all of whom were originally formed on 17 March 1911. The OMR saw service during the Battle of Gallipoli, with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and was later withdrawn to Egypt. The unit later served in served in France with the New Zealand Division becoming the only New Zealand mounted troops to serve in France.

The OMR played a crucial role as dismounted infantry with the New Zealand and Australian Division on Gallipoli in 1915, before being reduced in size in early 1916 and renamed the 1st Otago Squadron. In April 1916 the unit was moved with the remainder of the New Zealand Division to the Western Front where it formed a composite regiment with several Australian Light Horse squadrons. Initially part of I (1) ANZAC Corps it joined II (2) ANZAC Corps in July 1916 as part of the 2nd ANZAC Mounted Regiment with the Australian Light Horse units.

Going to war

Tpr. Stanley was given a cheery farewell by his elder brother Bernard whom he had nominated as his next of kin, along with the remainder of the Stanley clan and friends. Bill embarked on HMNZT 5 Ruapehu on 16 October 1914 at Port Chalmers with the remainder of the OIB and horses, split between two transport vessels, the other being HMNZT 9 Hawkes Bay. Both ships sailed north to Wellington to join the other NZ transports before they were due to convoy across the Tasman Sea.

The Main Body (plus the 1st Reinforcements) was the largest single group of New Zealanders ever to leave these shores. About 8,500 men – and nearly 4,000 horses would be transported in 10 troopships, which the government had requisitioned from commercial shipping lines. Before they were loaded with men, horses, ammunition, equipment and supplies the ships were hurriedly repainted a uniform Admiralty grey – one ship was completely repainted in less than four days!

On arriving at Wellington, the convoy learned their departure was to be delayed for three weeks whilst they awaited the arrival of a naval escort ship in the form of the armoured cruiser, HMS Minotaur and the Japanese battle cruiser IJN Ibuki. The previous offering of smaller, less well armed escort ships was considered by the NZ Military Forces as inadequate protection for the convoy. The transport ships returned to their home ports, or anchored in Wellington harbour and waited.

Once all ships had returned to Wellington three weeks later, the HMNZT convoy left Wellington Harbour on 16 October 1914 and headed towards Bass Strait where they liaised with several Australian transports carrying some of the A.I.F. troops. Together they proceeded to Albany, Western Australia which was the departure point for the complete convoy. A brief stop and some shore leave at Albany was permitted before the NZEF and A.I.F. convoy cast off (minus a few troops who either deserted or had drunk too much and consequently missed the departure) and made for Devonport in England.

A change of destination was advised whilst the convoy was at sea. The Ottoman (Turkish) Empire aligned themselves with Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria and entered the war in Nov 1914. Turkey’s occupation of the Middle East posed a direct threat to British shipping and the Suez Canal. As a result he NZEF and AIF would complete their training in Egypt and bolster the Imperial Forces guarding the Canal. Egypt therefore became the new destination. Once through the Canal, the ship’s disembarked troops, horses and equipment at Alexandria. The OMR disembarked on 03 Dec 1914 and entrained to what was to become the NZEF’s Base Camp for the Mounted Rifles, at Zeitoun which was situated about 9 kilometres north-east of Cairo. The Australian Mounted’s camp was ‘strategically’ located to the south-west of Cairo near the Giza Plateau and the Pyramids. Tpr. Stanley was posted to the 2nd ANZAC Mounted Regiment, Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Gallipoli

The first wave of attacks by the Australian and New Zealand Divisions that went ashore at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915 was met with fierce Ottoman resistance, both infantry and artillery. The mounted riflemen had not taken part in the initial landings since the Gallipoli Peninsula’s terrain was wholly unsuited to mounted operations. However, it quickly became apparent there was a desperate need for replacement men due to the unexpectedly high casualty rate being inflicted by a well prepared and obstinate enemy who dominated the high ground. This resulted in many of the Mounted Brigade’s troopers back at Zeitoun being mobilised and shipped to Gallipoli as fresh reinforcements for the New Zealand infantry companies.

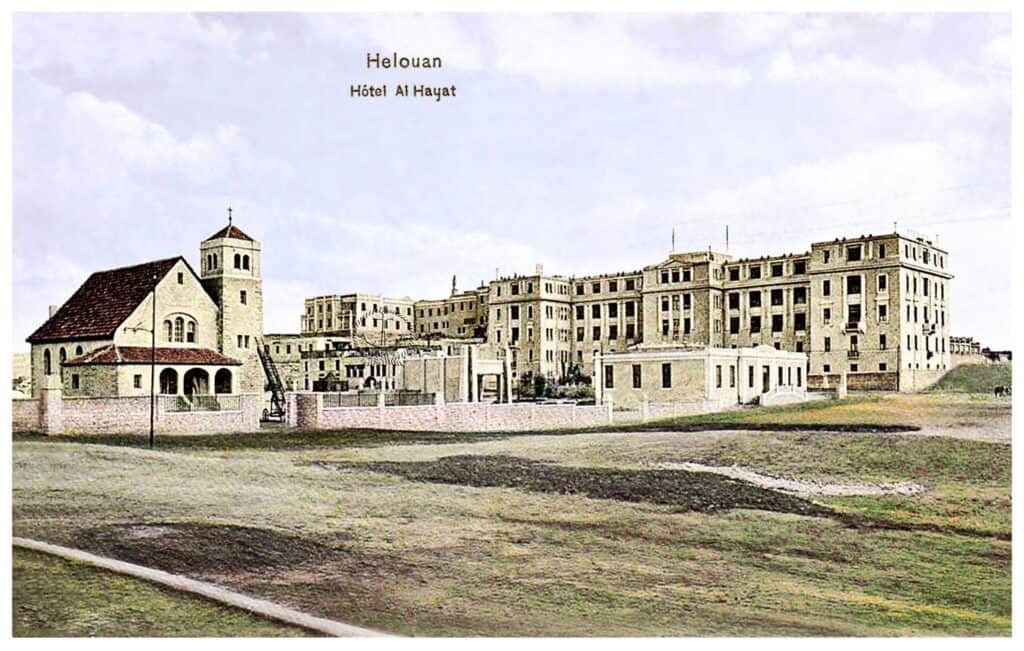

The Al Hayat Hotel at Helouan was one such facility. Here Tpr. Stanley was medically re-assessed, the result of which was he was declared: Medically unfit for active service although fit for employment in civil life. Stanley had been on the Peninsula for just five weeks before he sustained a Hernia injury. On 27 June he was evacuated to the HMHS Gascon standing off shore to receive casualties. After 53 days in the Gallipoli operational area, Tpr. Stanley was on his way back to Alexandria, Egypt. On arrival he was transported to the Al Hyat Convalescent Hospital Helouan (Helwan) on 8 July, formally the Al Hyat Hotel, one of many such facilities that had been requisitioned by the British High Command and converted to hospitals to manage the mass of casualties that flooded back from Gallipoli.

Bill Stanley (26) embarked on to HMNZT Tahiti for repatriation to Wellington on 11 Sep 1915. Arriving at Port Chalmers five weeks later, Bill Stanley’s homecoming was in complete contrast to his departure eleven months previous. His brother Bernard to whom he looked up to was no longer in Dunedin, gone with his family to live in Christchurch. Much had changed within the family and indeed the mood of the people in Dunedin was a complete reverse of that he experienced at his departure. It was a city suffering deeply from the effects of lost citizens, the loss of many young men who had been the hope of the city’s future – so many now were gone and many more would follow during the following three years of war on the Western Front! After a short period of leave in Dunedin, Bill had to attend yet another military Medical Board for his condition to be re-assessed by specialists in order to determine what level of treatment and rehabilitation was required for him. An operation was deemed necessary for the Hernia and scheduled for an undetermined date. Bill was duly discharged from the NZEF with effect from 11 October 1915, his Hernia operation pending subject to the availability of a surgeon.

Awards: 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18, Victory Medal + Silver War Badge (Services Rendered) awarded to any soldier honourably discharged as a result of wounds or sickness.

Service overseas: 331 days

Total NZEF Service: 1 year 42 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Returned to New Zealand

Bill Stanley’s history from here could be interpreted as that of a young man who felt he had let his mates down. He has arrived home unexpectedly early in mid 1915 (midway through the Gallipoli campaign) not with a genuine war wound, but a Hernia! How he must have felt – cheated, upset or embarrassed at not having done his bit can only be imagined, thoughts which no doubt would have played on his mind. We can only surmise how these might have affected young Stanley. Given the path his life took from here on, in retrospect it is not hard to see that elements of truth born out in various ways.

In spite of his service overseas in Egypt plus a little over a month in combat on the Gallipoli Peninsula during which he certainly would have been witness to the carnage that occurred on a daily basis, and have been subjected to shelling, bombing and machine-gun fire, he has been returned home not from any ‘real war wound,’ but a hernia! Added to this, Bill would be carrying the knowledge that many of those who he enlisted, trained and embarked with were dead (or would be in the coming years of the Great War). Knowing he had returned home through no fault of his own, so early in the war when thousands more were leaving on a monthly basis to fight (and die), I think anyone with a heart for this 26 year old, intelligent young man, can grasp the weight of guilt Bill Stanley might well have felt. As we know, the mind can take people who have been traumatised to dark places, black holes that deepen over time and which those so afflicted deal with in a variety of ways. The first and most obvious way in which war veterans over the centuries have dealt with these, is with liquor.

Such feelings could also rise to the top when veteran’s received their war service medals through the post. Often these were rejected as unimportant, even thrown away, as the represented yet another reminder of the things a veteran did not want to remember or acknowledge, or believing they were undeserving. Such thoughts may well have been part of Bill Stanley’s return to Dunedin.

By the time Bill had reached Dunedin his brother Bernard, wife Isabell and their five year old son Maurice Osborne Stanley, had moved to Christchurch. Bernard was listed on the WW1 Reserve Roll but fortunately was not called up. Initially residing at 6 Crobane Street in Sydenham West (now Addington) in 1916, Bernard moved his family the following year across the railway line to 54 Hazeldean Road while he remained employed as a Storeman.

With only married siblings remaining in Dunedin and employment hard to get, Bill Stanley went off into rural Otago picking up only odd-jobs his painful Hernia would allow him to do. Alcohol assisted in easing the pain, but would created and longer term problem. Why he had not been operated on when he returned is unknown. Perhaps the shortage of surgeons who had been drafted overseas for service may have been the reason. In 1919 Bill had taken on light farm work at Park Hill in Heriot when he received word the Hernia operation he so desperately needed, was scheduled for early 1920. He duly went into Dunedin hospital, the Army funding his operation as post service rehabilitation. Following several weeks of recuperation in hospital, Bill went to Christchurch on his release to stay with his brother Bernard and Isabell as part of his convalescence. It was here however, that trouble started to dog Bill Stanley.

Brushes with the Law

Since his discharge from the NZEF, alcohol had been Bill’s support mechanism and it was this that shaped a path of intermittent minor offending for the remainder of his life. His first court appearance in the Christchurch Magistrates Court was in July 1922. He was charged with being “drunk at the Christchurch Railway Station, and attempting to obtain a swag (a piece of luggage) from the Railways Department (Luggage Room) by falsely representing himself as an agent for one Charles East”. The Chief-Detective giving evidence said East had left his swag at the Railway Station, and had subsequently lost the reclamation ticket. Stanley had found the ticket and presented it in an endeavoured to get possession of the swag. In a sworn statement Bill Stanley said he had been asked by another man to get the swag for East. On the first charge of “Drunkeness” (an increasing problem for Bill) he was convicted and fined 10.shillings (NZ$1.00), or if in default 48 hours imprisonment. On the second charge of False Pretences, the Magistrate showed some leniency by placing him on Probation for two years provided he took out a Prohibition Order (P.O.) on himself – which he did. The P.O. made it an offence for Bill to drink, or to enter licensed premises, or for anyone to accompany him into a hotel, or for a Hotel Keeper, or anyone else, to supply him with liquor. The effectiveness of P.O.s was highly debatable as some publicans ignore them, they had no means of identification / recognition, and the accused often continued to drink in secret or have it supplied to them and so were not stopped.

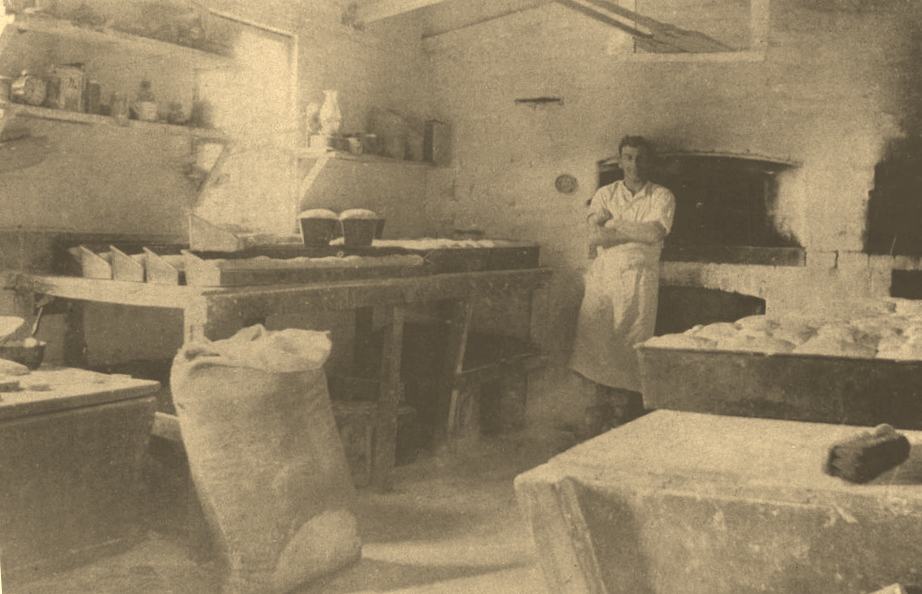

Bill Stanley settled his debts and headed back to rural Otago where he was relatively unknown. He ended up at Beaumont, the terminus of the branch line railway with a settlement population of around 245 (1916). Beaumont sits beside the Clutha River about 110 kilometres west of Dunedin near Raes Junction, between Roxburgh and Balclutha. Bill gave his contact address at this time as: C/o Mrs L. Johnson, Beaumont, Otago. Louis Johnson was the former Clutha River dredge-master who had taken over the Beaumont General Store and Bakery around 1920. Presumable Bill (34) worked in the store and delivered goods, as well as assisting baker Melville Dimmock in the bake-house.

Hereafter Bill Stanley began to be a regular inclusion in the Police Gazette for mostly alcohol related offences (at the lower end of the scale). Bill became more of a danger to himself than anyone else. The Gazette published the following description of him: Sometimes uses the name Bill OSBORNE (grandmother’s maiden name); Occupation labourer; height 5′ 8″, fresh complexion, fair/grey hair, blue eyes, medium/strong build. Tattoos: Clasped hands across his heart. Snake, dagger, and palm tree on right forearm. Two flags, crown, and “Egypt 1915” on right arm. Bird on back of left hand. Three dots on left wrist.

In March 1929, Bill (39) again fronted a Magistrate, this time at the Waimate Magistrate’s Court facing a charge of “being illegally on a premises without intent.” No mention was made of liquor however a semi-plausible reason must have been offered to the Magistrate which likely contributed to his only being “convicted and discharged.”

Great Depression

The Wall Street Crash in New York in August 1929 had the effect of initiating a world-wide economic depression, the so called “Great Depression” that during the ensuing months and year caused widespread unemployment with severe shortages of food and basic necessities. Many unmarried men, widowers and others hit the road, living the life of a ‘swag man’ carrying a few personal possessions in a swag and drifting up and down the country, from place to place seeking odd jobs in return for food and lodgings. Some travelled in small groups providing mutual company, security and support to each other as they drifted.

The pressure to put food on the table increased as unemployment rose in NZ which resulted in the government’s passing the Unemployment Act on 11 October 1930, an Act designed to spread the responsibility for the relief of hardship among all citizens, by the citizens. There would be no pay without work, with a number of futile work schemes put in place, made people feel as though there were second-class citizens, and this initiated the anger of the people towards the government.

There was a steady rise in unemployment in 1930. At the start of February 1931, around 8000 were unemployed, but, by the end to February 1931, however, the number of unemployed rose suddenly to 27,000. The figure continued to rise to 51,000 by June and up to a staggering 80,000 in 1933. This meant that 12% of the workforce was unemployed. Although this was the official figure released, the actual statistics were much higher as this figure did not include Maori, women or the underemployed.

The Act provided for an Unemployment Fund to be established for the relief of unemployment. To maintain the fund all male persons 20 years of age and over were required to register and, with some exceptions, to pay an annual levy of £1 pound 10 shillings ($3.00 – dollar equivalent), payable quarterly ($0.80). The collected levies that went into the Unemployment Fund were subsidised from the government’s Consolidated Fund. An Unemployment Board was appointed to assist in the administration of the Act and in particular to make arrangements with employers for the employment of unemployed persons, to promote the growth of industries, and to make recommendations for the sustenance allowances to be paid to unemployed persons. In conjunction with the Labour Department, the Board was to operate labour exchanges known as Labour Bureaus which managed the employment of those without jobs by the placement of suitably skilled men on critical tasks, and devising (questionable) work schemes for the remainder and the unskilled. The Bureaus paid out the sustenance allowances to those entitled. Initially, the maximum rates of sustenance were £1 pound 1 shilling ($2.05c) per week for each registered contributor to the Fund, plus £1 pound 7 shillings & 6 pence ($3.75c) per week for a dependent wife and 4 shillings ($0.40c) per week each for dependent child.

In 1931 the Unemployment Act was amended. The levy was reduced to 5 shillings ($0.40c) per quarter supplemented by a tax on earnings at a rate of 3 pence ($0.01) in each £1 pound ($2.90c), increased in 1932 to 1 shilling ($0.10c). The Levy was abolished in 1935.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

These circumstances no doubt impacted on Bill Stanley’s employment options and likely also contributed to an itinerant life and his brushes with the law that seemed to dog him. In June 1932, back at his brother Bernard’s in Christchurch, Bill was working as a Carter and got himself into hot water when for receiving stolen goods. His acceptance of a bicycle valued at £5.00 pounds from an unknown person, knowing it to have been stolen. The witness said he had bought the cycle for £15 pounds which had been stolen six and half years previously, and that he had not seen it again until he saw it in Stanley’s possession. Bill Stanley told the Magistrate he had received the bicycle from a drunken man who told him to take it to a second-hand shop and sell it. The Magistrate was unimpressed and netted Bill Stanley 14 days with Hard Labour in the Lyttelton Gaol.

While in Christchurch his sister-in-law Mabel**, the wife of his brother Bernard Osborne Stanley and mother of Maurice, died unexpectedly in 1930, aged 43. Bernard remarried almost eight years later in 1938 to Gore born, Jessie HOPE (b1891), a 45 year old spinster from No.10 Peterborough Street who conveniently happened to be living just three doors from Bernard and Maurice who were at No.3.

Bill remained with his brother and Maurice for the next couple of years after Mabel’s death, taking labouring jobs in Christchurch. After Bernard and Maurice moved into a flat at N0.3 Peterborough Street in the city centre, Bill returned to Otago. He got board and labouring work at Pembroke, the former name of Wanaka. While at Pembroke, Bill managed to incur the wrath of the Labour Department over a breach of the Unemployment Act as he had failed to pay mandatory quarterly levies. These were payments made to ensure some level of income would be payable at times when Bill was out of work during the Depression years. The result was a stern faced interview with a representative from the Department which resulted in arrangements being put in place to make good on the debit. In August 1937, this scenario was repeated. The Labour Department was again hot on Bill’s trail for unpaid levies. Further warnings and threats of prosecution were issued if he fail to repay the debt. This must have seemed a nonsense at the time as the change of the government at the end of 1935 had the effect of abolishing the Levy in 1936. But it seemed outstanding monies owed to the Unemployment Fund until the date of abolition, remained payable or prosecution and gaol time would likely result.

Whether the debt was paid or not is unknown, but a perusal of the Electoral Roll and Wise’s Post Office Directory for Canterbury, Otago and Southland at this time showed no evidence of Bill Stanley’s location or employment. He had apparently left Otago sometime in 1938 or 1939.

Note ** The PRESS recounts the tragic circumstances of Bernard Osborne Stanley’s wife Isabella Mabel Stanley’s death in Christchurch in 1930. Mabel Stanley was driving her car at night in Christchurch when, at the corner of Manchester and Belfast Streets, she inadvertently knocked down to male visitors to the city who were crossing Belfast Street. Both men sustained serious injuries. One of the men, from Dargaville, died later that night. Mrs Stanley was subsequently charged and although an accident, pleaded guilty to ‘negligent driving a motor vehicle causing death’ on the night of 21 February 1929. The jury were bound to find her guilty but made a recommendation for mercy because of Mrs Stanley’s nervous state of health. Mable Stanley was convicted and disqualified from driving for life. The second man, a gardener from Auckland, lodged a claim with the court for compensation of £2138 (1929-NZ Pounds Sterling = $212,878.00-2020). The claim was settled out of court.

On 28 June 1930 Mabel Stanley (43) was found dead in a gas-filled room of her home at 173 Riccarton Road. Poor Mabel Stanley had been so distraught over the man’s death, the court case and compensation (and no doubt the subject of local gossips), it seems she never got over this tragic event very sadly took her own life.

Orui Station, Riversdale

Searching Electoral Rolls further afield, I finally located Bill Stanley on a Masterton Roll working at the Orui Station. The coincidentally named Mr William Robert “Bill” LEVIN was the Manager of Orui Station, a large beef and sheep farm situated in an isolated area surrounded by trackless, rugged bush on the Wairarapa coast near Riversdale Beach, about 50 km ESE of Masterton. The Levins were early settlers of the Wairarapa, the town of Levin being named after Bill Levin’s grandfather. Manager Bill Levin had attended Wanganui Collegiate, stared in the Collegiate’s Rugby XV and was a Prefect in 1922/23. He subsequently went to Cambridge University and whilst in England demonstrated his prowess as a horseman and cattle wrangler to win the Rodeo Exhibition at Wembley in 1924. On his return to Masterton, Bill Levin established W. R. Levin & Co., an agricultural stock and station agency to service the local farming community. The company was also an agency for buying and selling wool, stock as well as farm supplies and machinery.

Orui Station’s non-resident owner was Capt. Richard (Dick) Errol Wardell Riddiford to whom the Levin family was ancestrally connected. A First World War officer in the Otago Mounted Rifles (Bill Stanley’s unit) and later of the Wellington Mounted Rifles, Riddiford became the Aide-de-Camp to Major General Sir Andrew Hamilton Russell, KCB, KCMG (23 Feb 1868–29 Nov 1960), the NZ General Officer Commanding in France. He was decorated with the Military Cross for bravery in the field in France, was twice Mentioned in Dispatches, and at war’s end was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). Whilst returning to England in 1918 at the end of the war, Riddiford (33) died from influenza. As a consequence W. R. “Bill” Levin was contracted to manage the Station. Bill Stanley had most likely been employed in his capacity as a Returned serviceman, by Bill Levin who would have been short of eligible men to run the Station because of the Emergency Regulations that were imposed on the country to call-up men 20-45 for war service. Masterton at this time was also a ‘dry’ area of the country where prohibition had been staunchly entrenched. This would have no doubt kept Bill out of trouble for a while.

Orui Station was originally spread over 17,000 acres. The Orui-Riversdale block was awarded in 1852 to Edwin Meredith, who came to NZ as a young man. His father was a well-to-do retired Naval Officer who with his family had worked the land in Tasmania. After having leased land in several parts of NZ, Edwin was the first applicant for a large block of land south of the Whareama River that the Government had just purchased from the Maoris. After having been granted the land, Meredith sent all his possessions and timber for a house by schooner from Wellington but it was all landed at Castlepoint 12 miles away through trackless bush. A raupo hut was built for the family and staff to add to an existing three bed roomed whare until possessions could be brought back. By 1867 Meredith’s health had deteriorated and he tried to sell Orui and Uriti (part of Riversdale) but it did not sell.

In 1878 it was again proposed to sell seven blocks of up to 1500 acres, but this idea was stopped and sons Edwin and Richard started leasing it for 10 years from 1879. An 1879 sub-division saw Edwin take Wairongo and Richard take Beaumaris – Edwin died in 1885 age 21 and Richard died in 1896 aged 39. The Orui Station in 1893 contained 8,780 acres, although the family holding in the three stations was 21,000 acres. In March 1907, Orui was sold to Cunningham and Midgley who then sold it six months later in September 1907 to R. E. W. Riddiford. The management of the Station was in the hands of W.R. Levin and Company of Masterton until it was sold to a partnership, one half of which was from the original owner’s family, Clarence Meredith in 1946. The other half of the partnership was the P. J. Borthwick Trust.** In 1954, Clarence Meredith bought Orui outright, thus returning it back into the Meredith family in whose ownership it still remains. Today Orui Station is a tourist destination that offers fully catered New Zealand walking adventures over private farmland and Wairarapa coastline with options of one day, two nights/two days, or three nights/two and a half days. The farm buildings accommodate weddings and various specialty events in this very scenic location, now only a 40 minute drive from Masterton.

Note: ** The Te Whanga Angus stud, 20km south of Masterton at Gladstone, was established in 1936 by P.J. Borthwick and initially purchased cattle from the Waiterenui and Pharazyn studs. Te Whanga was used as a training farm for returned servicemen after World War II. Located at Gladstone in the Wairarapa, the 1650 hectare station is home to 10,000 sheep and 700 Angus cattle.

Being a Returned serviceman, it is possible that Bill Stanley had learned of the training farm to be established at Te Whanga and had gone to Masterton on the pretext of seeking work. Whatever his physical limitations were which may have been about by his varicose veined legs and age, might possibly have been the reason he was employed as one of the cooks for the station labourers, shearing gangs and cattle wranglers at Orui. Another plus was that Masterton at this period in time was ‘dry’, one of the few areas in NZ that still prohibited the sale or manufacture of liquor which can only have done Bill’s health some good.

World War II

New Zealand’s contribution to the Allied Divisions of the British Army in North Africa was an Infantry Brigade, the beginnings of which were raised in Oct 1939. The First of three Echelons of men numbering around 6,500 in each, departed in January 1940, followed by the 2nd Echelon in May and the 3rd Echelon in late August 1940. Bill Stanley had registered as all males over 19 years of age were required to do, however at 49 years and 5 months old in Jan 1940, he was not likely to be selected for overseas service. Bill volunteered for Home Service (the Home Guard) and was required to undergo a Medical Board. He gave his address at this time as No.3 Tasman Street, Mt Cook, the suburb directly below the present day Wellington Museum and Carillon, the site of the former Mt Cook Prison. An old Wellington map of the area defines No.3 Tasman Street being part of the Salvation Army’s Peoples Palace complex which was positioned directly across the road from the Mt. Cook Police Station. Given his enlistment occupation was “Cook”, it might be assumed he was employed as a cook in either the Salvation Army or Police Barracks kitchen? The Barracks in fact was the former Mt Cook Prison closed in 1900 but re-opened in 1913 to accommodate the Special Police recruited to deal with the 1913 Strike in Wellington. In the 1930s during the Great Depression, the former prison was used to accommodate the homeless. Given his brushes with the law I would pick he was more likely to have been cooking for the Salvation Army facilities which would also offer accommodation. Bill may even have been taken in by the Salvos by way of assisting him with his drinking, whilst also offering him work and board.

Home Guard

National Service Emergency Regulations were invoked from June 1940. Difficulties filling the 2nd and 3rd Echelon with volunteers necessitated that the 31 May Defence Act and the Emergency Regulations Amendment Act, be amended to require all men between 19 and 45 years to register for military service if/when called up by ballot. Prior to this eligible men who volunteered for service were able to submit a preference for service, e.g. to serve in the Navy, Army or Air Force.

A Home Guard modelled along the British HG was to be formed in August 1940 for the purposes of defending NZ against invasion posed by Japan. Initially its ranks were to be filled with volunteers from 15 years to no upper age limit. In 1942 it became compulsory for all men between 35 and 50 to enlist in the Home Guard. Bill Stanley volunteered to join the Home Guard in 1940, just one month shy of his 50th birthday. His Next of Kin was recorded as his brother, Ernest Frank Stanley, then a resident of Port Chalmers.

Boys and men volunteers were accepted for the Home Guard, the youngest age limit being 15, however there was no restriction on the upper age limit (this changed in 1943 when enlistment became compulsory for all men 35-50 years of age). All volunteers for Home Service were accepted subject to their medical and physical fitness, with quite a bit of latitude extended. Bill attended his Army Medical Board in June 1940 and as is shown in his military file, was medically Graded 1A. Grade 1 meant a single man that was fit for service anywhere – at home or overseas. Grade 1A was applied to: Personnel suitable for Grade I, but who are subject to such minor disabilities as can be remedied or adequately compensated by artificial means; i.e. personnel suffering from some temporary or remedial disability, and whose convalescence is proceeding satisfactorily.

It is apparent from his medical documents the Board doctors had considered Bill’s age together with his previous ailments, which included: Encephalitis in 1910 (swelling of the brain, usually the result of a viral infection), the Hernia operation in 1920 and broken right leg in 1934. In addition the Board noted he had varicose veins in both legs. Collectively these were reason enough for the Medical Board to stamp his documents with “ENLISTMENT CANCELLED.”

This really must have been the last straw for Bill Stanley – having endured his own personal ignominy in returning from Gallipoli early in mid 1915 with the Hernia, his brushes with the law and with alcohol, now he could not even become a volunteer for the Home Guard.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bill Wellington and drifted south again, back to Christchurch and then on to Timaru. Trouble was not far away – in August 1941, Bill was in court again. After reading out a number of false pretence, receiving stolen goods, and assault offences to the Timaru Magistrate, the Police prosecutor also informed his Honour that the accused, Bill Stanley, in addition to the charges, had only been released from gaol that same day! The Police alleged that whilst staying in a Timaru private hotel, William Stanley had allegedly stolen two blankets and four pairs of sheets valued at £3 pounds and 5 shillings (NZ$10), being the property of the Trustee of the estate of Richard Cumming Kebbell, which were found to be missing after Stanley had checked out. A second charge proffered by the Wellington Police, alleged that William Stanley had also stolen Richard Kebbell’s pocket watch and chain, valued at £3 pounds and 5 shillings (NZ$10) and the property of the Trustees.

On the first charge he was found guilty and awarded another 30 days in gaol. On the second charge, Bill Stanley was bound over to appear before the Wellington Magistrate six days later for the alleged watch theft – if found guilty, the sentences would be combined and served in Wellington’s Mt Crawford Prison. It was alleged Bill Stanley had ‘liberated’ these items from Kebbell after he had died in the private hotel where Bill had also been staying.

A big night for Bill on Christmas Eve 1941 resulted in yet another visit to the Christchurch Magistrates Court for being drunk and disorderly. He was fined £1.pound (NZ$3.00) however he defaulted on paying the fine and was hauled up again before the Magistrate again. As a consequence, he spent Christmas Day and Boxing Day in Paparua Prison. On 27 Jan 1943, Bill was again in trouble whilst under the influence of liquor, this time in Ashburton – the Magistrate sentenced him seven days in gaol with Hard Labour for assaulting John Hunt, the owner of a billiard saloon who had remonstrated with Bill after he had interfered with two of the players. On his release seven days later, Bill was required to return to Wellington to face the outstanding watch theft charge. Before the Magistrate on 16 Feb 1943, Bill (53), a labourer, was sentenced to two months in gaol with Hard Labour by Mr. Justice Blair for stealing the watch and chain valued at £3 pounds and 5 shillings ($11-12), the property of the Trustees of the Estate of the late Richard Gumming Kebbell.

Bill’s life appeared to be spiralling ever downwards. To cap off this latest indiscretion, when Bill was released after completing his sentence he was faced with the news his elder brother Bernard, the man he had depended upon for support from the time their parents had died, had himself died suddenly at his home in Peterborough Street. Bernard’s son Maurice (Bill’s nephew), now a grain merchant, had by this time married and moved to 18 Mathias Street, St Albans to be much closer to his step-mother Jessie Stanley’s house at 16 Berry Street.

Somewhat lost without his brother, and with Maurice married and gone, Bill Stanley returned to Wellington. At 55 years of age, Bill continued to seek labouring jobs whilst moving from place to place around the city, generally in the Mt. Cook-Te Aro areas of town. Accommodation was cheap and available but definitely with no frills. By the mid 1950s, Bill was in his mid sixties and employed as a Watchman (security guard) in Cambridge Terrace, a job he managed to stay with for the better part of ten years whilst also living at 65 Cambridge Terrace, a boarding house. In 1957 Bill’s address was listed in the Wellington Census as Fort Dorset, an Army Camp situated on the Miramar Peninsula built around 1900 in order to defend Wellington harbour. During the Second World War, the fort was fully operational and consisted of observation posts, 4″ and 6″ coastal artillery guns and searchlights. Here Bill was employed as a labourer and no doubt found much in common with the soldiers working there, particularly on Anzac Day when he would be able to wear his three medals for Gallipoli service. I suspect Bill would have felt more ‘at home’ in this military environment than he had done in years. By 1963 he was living at 31 Marion Street in Te Aro but for how long, is not known. His last known address, still in Te Aro, was 71 Hopper Street where Bill lived out the last years of his life.

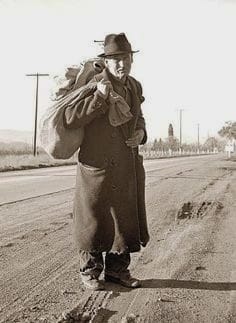

Bill’s elder siblings once married of course had their own lives and families to concentrate on, which for some of them would be interrupted by the early deaths of their own spouse or children. Bill’s itinerant life was not uncommon for many men who returned from the front, shattered by their unforgettable experiences and who frequently found solace in alcohol, never really feeling as if they fitted back into the society they had left. Overlaid on this was the impact of the Great Depression in the 1930s when hardship, food shortages and unemployment saw men of all ages from all walks of life destitute or in a state of utter despair, reduced to eating at soup kitchens and while many lived a swaggies lifestyle, wandering the back roads of New Zealand picking up odd jobs for food and shelter or begging for handouts.

Bill Stanley’s circumstances were far from unusual albeit his were possibly impacted to a greater extent by the personal misgivings he may have felt over his truncated overseas service. The loss of friends and work mates killed, wounded or who died of disease while at war, doubtlessly exacerbated by his own anguish in not being able to be with them, to back them up as is every soldier’s obligation. The term “survivor guilt” is one that might well have described Bill Stanley’s feelings on his return. Amazingly, this life-long bachelor kept going until he was 82 years of age.

Former Trooper William Robert “Bill” Stanley died on 2nd December 1971 at the Central Park Hospital in Wellington and was given a returned soldier’s burial in the Soldiers Section of the Karori Cemetery.

~ Lest We Forget ~

Trooper Stanley’s descendant kin

Bill Stanley’s eldest brother was Percival Alfred Stanley (1881-1957), a Storeman and later Quarryman, who married Catherine HOUSTON (1881-1915) at Dunedin in Oct 1909. From their union they had two children – Percival James “Jim” Stanley (1911-1971) and Alfred Ernest Shacklock Stanley (1913-1981). Sadly Catherine (34) died on 6 October 1915 after just six years of marriage in what can only be described as bizarre circumstances, well reported in the newspapers of the day. The short version: Catherine was pregnant and had requested her husband to get her some ‘special’ pills she had specified from a woman she knew in Forbury, for use as a precursor to procuring an abortion of a child she and her husband could not afford. The failed attempt resulted in her being rushed to Dunedin Hospital where she later died. Her husband Percy was accused of being complicit in giving her a noxious substance knowing it was to be used for an unlawful purpose. His actions while condemned by the Coroner were successfully defended by NZ’s foremost barrister of the day, Alfred Charles Hanlon, King’s Counsel.

Percy A. Stanley was 53 when he re-married 52 year old Margaret Grieve MORRIS (1881-1960) in 1934 with whom he had two further children, Gordon Stanley (b1920) and Norman Cecil Stanley (b1924).

Medal returned to Stanley family

Percy A. Stanley and wife Catherine’s first born son had been Percival James Stanley (Percy Jnr.), better known as “Jim”, who married Margaret Ann RODGERS (1913-1967) in 1934. Jim and Margaret had 10 children altogether, their first being Roger James (1934-1970), Frances Catherine (1935–), Brian Charles (1937-), Ngaire Honora (1940-2015), Keith Alfred (1941-2006 – a Vietnam veteran), Eric Henry (1944–), Graham Percival (1945-2014), Robert Ian (1946–), Carolyn Margaret (1947–) and last, Linda Georgina (1950–) Stanley.

Robert Stanley married Maureen Joy Bamber (b1948–) at Dunedin in 1965 and together had a son and daughter, Michael “Mike” Ian Stanley (b1965–) and his sister Terresa Ann Stanley (b1968–). Robert Stanley is the grandson of Percy Alfred Stanley (Tpr. Bill Stanley’s elder brother) thereby making Robert the grand-nephew of Tpr. Stanley. Robert’s son Mike and daughter Terresa are therefore the great grand-nephew and niece of Trooper William Robert Stanley.

Having studied his family’s genealogy, Mike Stanley was aware of his great grand-uncle’s chequered (mis) fortunes since returning from Gallipoli. Mike said when he opened the package containing Bill’s medal, he couldn’t help being very moved thinking of Bill Stanley at that moment, his war experience and the apparent loneliness as he drifted through his life from place to place, labouring long into his senior years. Bill Stanley could not in any way be blamed for living the life he did. With both parents gone before he had left home, young Stanley had to pretty much get on and make his own way in life. Being the youngest and only son to go to war, to be rejected from Gallipoli for a Hernia, must have been truly disappointing and quite likely coloured both his outlook and future from then on.

We often read of the lives of war veterans who have returned home suffering from the ‘scars of war’, their physical scars more obvious than the mental ones. These, of which little was then known (e.g. shell-shock) continued to exact a toll by inflicting an ‘inner war’ the enemy’s bullets and shells failed to finish on the battlefield. Bill Stanley never married nor had any children. Whether or not he would have liked the stability a family and home of his own might have bought, it was not to be. In spite of his itinerant lifestyle, alcohol abuse and trouble with the law, Bill was harmless and more a victim of circumstances and the time. For all that, Bill Stanley survived until the grand old age of 81 however, he died alone in a Wellington Hospital, miles from his Otago home and anyone he had ever known. This was indeed a tragic end for the bright and educated young man from Caversham whose life without Gallipoli may have had a very different ending.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

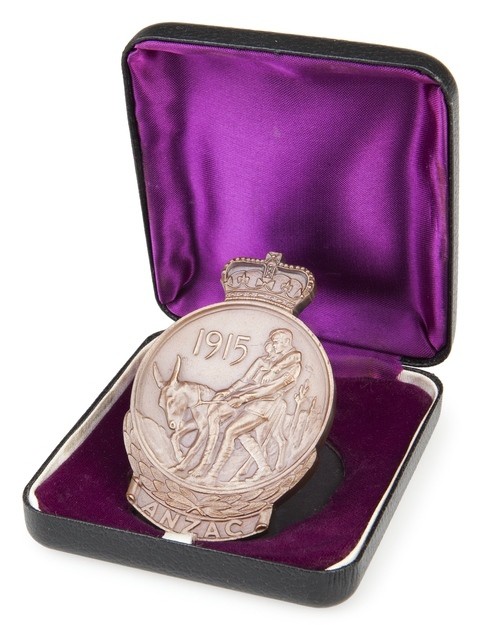

Bonus medal

One of the parts of this job I really like is the discovery of unclaimed medal(s), many of which still remain available to descendants more than 100 years after the event. In 1967, the 50th anniversary of the landings at Anzac Cove, the New Zealand and Australian governments decided to issue the ANZAC Commemorative Medallion (often referred to as the ‘Gallipoli Medallion’) as an acknowledgement to those who served in the Gallipoli campaign. The Medallion was available to all Gallipoli veterans upon application. Living Gallipoli veterans also received a miniature version of the medallion with their regimental number stamped on the rear, to be worn as a Lapel Badge. For veterans of Gallipoli who had died either on Gallipoli or thereafter, the Next of Kin of the veteran could make a claim for the Medallion as a family keepsake. Next of Kin could not claim the Lapel Badge.

Although Tpr. Bill Stanley did not decease until 1971, no evidence was found that a claim has ever been made for his medallion entitlement. Mike Stanley has made application for Bill’s Stanley’s ANZAC Commemorative Medallion.

Missing medals

If you are able to help Mike locate the other two medals named to Tpr. William Stanley – British War Medal, 1914-18 and the Victory Medal, we would like to hear from you. Mike would like the opportunity to negotiate a buy-back. Please contact MRNZ if you can help.

The reunited medal tally is now 334.