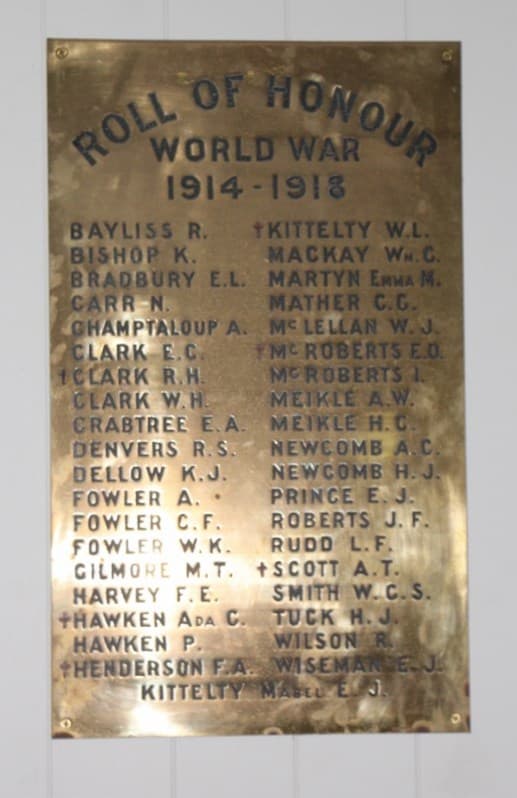

12/25 ~ WILLIAM LESLIE KITTELTY

In 2015, a New Zealand descendent of the Kittelty family now living in Australia, made enquiries through the New Zealand newspaper network looking for the medals of her Great Uncle, William Leslie Kittelty, that had not been seen by any in the family for many years and were presumed lost – forever!

Phillipa Meppems is the grand-niece of Bill Kittelty while Bill’s younger sister May Moutray (Kittelty) McKECHNIE is Phillipa’s grandmother. Her attempt to find Bill’s medals was the subject of an article on unclaimed First World War medals, by Auckland reporter David Lomas published in a Sunday-Star Times article on 07 April 2015 – “Campaign to return WWI medals to families” was published just three weeks prior to the 100th Anniversary of the Gallipoli Landings on 25 April 1915. David wrote (in part):

“Campaign to return WWI medals to families”

By David Lomas, 18 April, 2015 (Sunday Star-Times)

About one thousand engraved First World War medals are being held in a New Zealand Defence Force storeroom, still in their original wrapping, waiting to be collected by relatives of returned soldiers.

The medals were supposed to be delivered to the soldiers during a mass Government-funded mail out between 1920 and 1924. However, while about 99 per cent were delivered to the next of kin of the 18,000 men who died and the more than 80,000 men who returned from the war, about 1000 men could not be located. Their medals have sat in NZDF’s stock room ever since.

A NZDF spokeswoman said the Government had made a real effort to distribute all the WWI medals during the 1920s. All medals that were returned labelled ‘gone – no known address’ were investigated and the recipient was often found. The uncollected medals are not for valour, but recognise the different campaigns service personnel served in.

“They (the undistributed medals) are the medals of the silent soldiers,” said an RSA representative. “The guys who got off the boat and walked away and went back to the farm, the factory, the office and never wanted to talk about the war or their experiences ever again.”

“It’s sad because a lot of those men have now passed away. Their sons and daughters, grandsons or granddaughters should be wearing their medals – representing them.”

Whether a medal has been issued is recorded on the recipient’s military file. The NZDF estimates that 99 per cent of service medals were delivered to WWI soldiers.

While some medals sent out in the mass mail out were returned ‘gone no known address’ further inquiries resulted in the medals “nearly always reaching their intended recipients,’ according to a spokeswoman.

With so many returned servicemen and servicewomen having passed away the NZDF has set up a strict pecking order for relatives wishing to apply for the medals. Top of the list is beneficiary designated in a will. Then the order is: widow or widower, child, stepchild, grandparent, sibling, half-sibling, niece or nephew and other person named as next-of-kin in official documents.

The centenary of the Anzac Landings has moved many Kiwis to action, determined to track down their forebears medals, or return medals in their possession to the families of those who earned them.

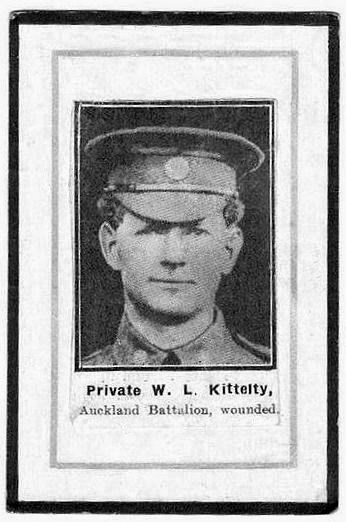

New Zealand-born Phillipa Meppem, 57, now living in Sydney, is trying to find the medals of her great uncle William Kittelty who died while serving with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force at Gallipoli. She is also trying to find the medals of her great aunt Mabel Eliza Kittelty who served for three years with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service Corps in Europe.

“I would love to find them, especially with Anzac Day coming. I don’t want them to be forgotten,” she said.

William Kittelty was among the first troops landed at Anzac Cove and early in the battle for Gallipoli he was shot in the arm. After treatment in Egypt he returned to Gallipoli six weeks later and died in August during an attack on”The Pinnacle”.

* Can you help find the Kittelty medals? Email *****

Original newspaper story: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/67855394/campaign-to-return-wwi-medals-to-families

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Immigration from Tasmania

The Kittelty family of Greymouth were of Scottish stock centred on Aberdeen in Perthshire. The proliferation of the Kittelty’s in the southern hemisphere started with the arrival of William KITTELTY Snr. (1813-1883) at Hobart Town, Tasmania.

William was 26 years of age in March 1839 when he married Eliza STEVENS (1819-1870) at the Mission House in Hobart Town, a young English girl from Roberts Bridge in Sussex. After their first daughter Sophia was born, the Kitteltys moved to Melbourne where their first son was born, William Norman Kittelty in 1841. Sophia died before he first birthday however a subsequent move to Geelong resulted in six further children. In 1852 the Kitteltys moved to Colac in country Victoria before joining the ‘rush’ for anticipated riches from the goldfields of Ballarat which had tempted thousands of prospectors from all over the world. Four more children born in Colac and Ballarat bought the Kittelty’s total children as at to ten, some of whom did not survive beyond infancy.

William and Eliza Kittelty’s fortune was not to be made in Australia. With subsequent discoveries of gold in New Zealand at Thames, Otago and on the West Coast, William and Eliza with their family of ten (William Norman being the eldest at 20 years old), crossed the ‘ditch’ in the early 1860s, eventually settling in Greymouth on the West Coast.

Solomon (53, brother of Wm. N.), Esther ”Daisy” (15), Esther, (48, mother), Norman William (23), W. L. “Bill” Leslie (14), May Moutray (11), Mabel Eliza Jane (15), William Norman (59, father), Harold Oscar (12), Solomon “Sol” (17), Maria Elizabeth (20) Kittelty.

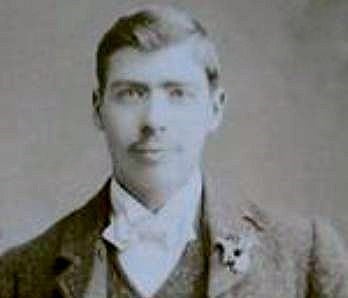

William Norman Kittelty (1841-1913) in due course married Irish girl Esther MOUTRAY (1852-1930) from Belfast, Antrim. The couple were married at Greymouth in 1875 and established their home interestingly, in William Street! William, a storeman, and Esther had six boys and five girls, all born in Greymouth: Victor Albert Kittelty (1876-1886), Norman William Kittelty (1877-1955), Charles John Burgess Kittelty (1878-1895), Maria Elizabeth Kittelty (1880-1961), Mabel Eliza Jane Kittelty (1879-1969), Olive Sarah Kittelty (1882-1882), Solomon “Sol” Kittelty (1883-1903), Harold Oscar Kittelty (1888-1918), William Leslie “Bill” Kittelty (1886-1915), Esther “Daisy” (Jnr) Kittelty (1885-1968), May Moutray Kittelty (1889-1964), Victor Norman Kittelty (1909-1973). As can be seen a number did not survive beyond their teens. Those who did with one exception, moved from Greymouth after the death of their father and settled in and around Auckland,

William and Esther’s eighth born child was “Bill” Kittelty. Raised in Greymouth, Bill became a carpenter whilst his elder sister Mabel with whom he would become linked professionally in later life, took up the work of so many young women in those days – dress making. A large family meant many mouths to feed and so everyone had to work as soon as they were able. There was eight years the difference between Bill and Mabel however little did they know then that both would serve overseas during the First World War, but only one would come home again.

In January 1913, the then senior Kittelty male, Esther’s husband William Norman Kittelty died in Greymouth leaving widow Esther at home with three spinster daughters – Mabel, “Daisy”, and May Kittelty. By this time young Bill Kittelty was living in Auckland, having taken a job as a carpenter with the firm of Craig Brothers Builders in 1912. Bill at that time was living at 76 Prospect Terrace in Mt Eden and it was here that his mother Esther and Bill’s three sisters stayed temporarily while they sought permanent accommodation nearby. Esther Kittelty and the girls soon found a house about 200 meters from Bill, at 12 Eglinton Avenue, Mt Eden.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

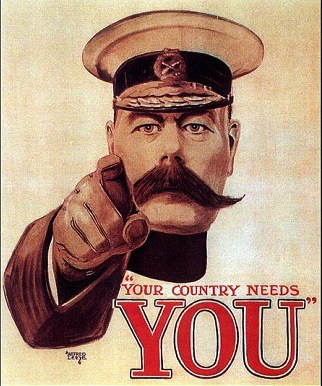

A ‘Call to Arms’

The limitations of those who with physically and medically fit for overseas service, and between the ages of 20 and 45, only were accepted initially. Bill jumped at the chance to go and was accepted for the first group of New Zealanders to go overseas. Referred to as the Main Body this first group would also consist of the First reinforcements that were anticipated to be necessary to replace those who became casualties.

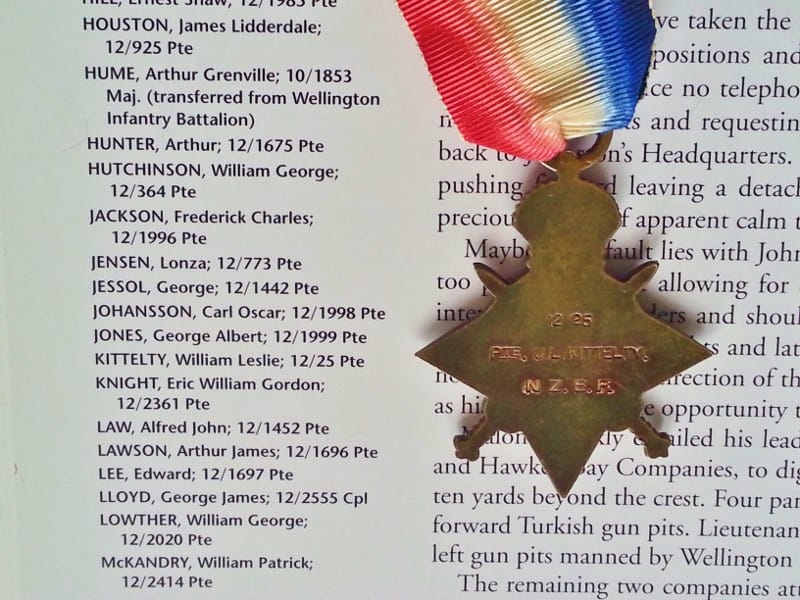

12/25 Rifleman William Leslie (Bill) Kittelty, a territorial mounted rifleman with the Hauraki Squadron, was placed with the 1st Auckland Infantry Battalion who were assembled at Epsom (Alexandra Park) to complete their Attestation (contract) which bound them to serve for the duration of the war. Here they underwent the fundamentals of soldiering and horsemanship. More in depth training and preparation would occur once they reached their destination in England. A number of training camps were being built to accommodate the Empire’s forces for their administration and training before going to the front in Europe.

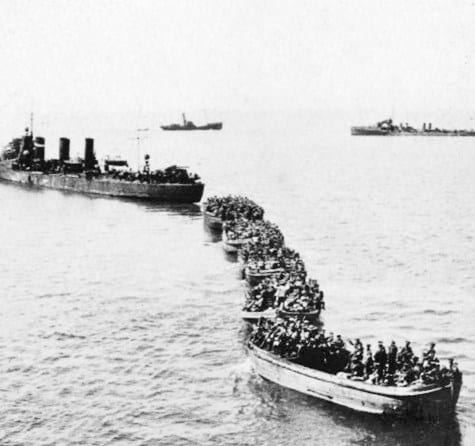

Rflm. Kittelty embarked on HMNZT 12 Waimana and left Auckland on 24 Sep 1914 along with the 8,500 men from all parts of the country who comprised the Main Body. A convoy of 10 troop transport ships had embarked troops (plus horses of the Mounted Riflemen) at Auckland, Lyttelton and Port Chalmers and were assembling at Wellington when an unexpected delay was imposed. Because of the perceived weakness of having only four smaller light escort ships for the convoy’s protection, the convoy had to await for another two armoured cruisers (HMS Minotaur and the Ibuki – Japanese) to arrive.

Finally on 16 October 1914, the convoy re-assembled in Wellington and set sail for Hobart. After gathering additional ships and troops of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) Main Body from Hobart and Albany in Western Australia, the now 44 ship convoy (included 28 Australian ships) proceeded to Colombo and then on to Egypt. The NZEF Main Body were prepared for their winter arrival in England where they would undergo several months of intensive training and rehearsals before being landed in France and transferred by train, vehicle and on foot to the Western Front.

Queen of fundraising

Queens Carnivals were a popular fundraising initiative in the 20th century. During the First World War, carnivals included performances, parades and the sale of local produce.

Usually, a dozen candidates (such as Queen of the Seas, Queen of the Dardanelles, Country Queen, Queen of the North) competed to be elected the ‘Queen of the Carnival’, with the winner pronounced queen in a coronation ceremony. In the lead up to a carnival, the Queens were tasked with fundraising for returning soldiers, their families and war refugees.

The Auckland Patriotic Queen Carnival 1915

Twelve candidates competed to be Queen in the Auckland Carnival in 1915. The New Zealand Ensign named “Our Soldiers’ Flag” was a fundraiser for the Soldiers’ Queen, Mrs Alice Wallingford, who was the wife of Captain Wallingford.

Mrs Agnes Keary embroidered names on the flag for a ‘gold coin’ fee of ten shillings each. It proved so popular that names kept being added even after the carnival had finished. The flag was presented during an fete at Point Erin Park. More than 20,000 people attended the event, which was organised by the Ponsonby unit of the National Reserve in support of Mrs Wallingford’s fundraising efforts. The New Zealand Herald reported:

Excerpt from an article from the New Zealand Herald, Volume LII, Issue 16057, 25 October 1915, Page 4.

“During the evening the Union Jack presented to the group by Mrs A J Keary was unfurled, and the names of many Auckland soldiers now at the front will be embroidered on the flag as a result of the gold contributions received. Dainty souvenir programmes containing an autograph photograph of” the Soldiers’ Queen were sold in large numbers.”

The flag is embroidered with the names of the Hauraki Squadron of the Auckland Mounted Rifles. At the centre of the Jack is the name of Cyril Bassett, VC. The flag fundraising initiative raised £305 for the Auckland Wounded Soldiers’ Fund.

Mrs Wallingford placed fourth in the Queen Carnival, held in Auckland in November 1915. In the 10 weeks leading up to the coronation, nearly 21 million votes were cast – at a price of threepence per vote. The carnival raised a total of £269,000 ($37 million today).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Within weeks of being at sea, Pte. Bill Kittelty and the remainder of the Auckland Infantry Battalion and other Main Body units were informed the war on the Western Front had stalled and Turkey had now entered the war (Nov 1914), aligning itself with the Central European powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Their destination for the Main Body was now Egypt and to ensure the Suez Canal remained securely in British control. An Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) made up of New Zealand and Australian Mounted Rifles Brigades would provide defensive protection of the Suez Canal against any Ottoman attempts to seize it.

HMNZT 12 Waimana arrived at Suez on 30 November after 48 days at sea. Once through the Canal, the ship entered the Mediterranean and proceeded westward to the port of Alexandria where the Main Body was disembarked on 03-05 Dec 1914. After disembarking, the troops were entrained to the NZ Base Camp at Zeitoun, about 9 km NE of Cairo, where their preparation and training was to take place. Of course the troops had been prepared for training in England wool uniforms would have provided adequate defence against the cold of the northern hemisphere winter, however they were completely inappropriate for the desert like climate of Egypt which would only get worse in summer. Overheating, heat stroke, fainting, rashes, dehydration, etc would afflict many of the men, a problem the command did not need but had to take into account very quickly and organise tropical clothing which would take time to arrange. For the Main Body however, wool was what they were stuck with.

Both Infantry and Mounted Rifles units started acclimatisation and training in earnest for the forthcoming operations.

Gallipoli Campaign

The British naval attack on the Dardanelles Straits during Feb – Mar 1915 was a failure despite a couple of enemy ships being sunk, however the attack had also precipitated a strengthening of Turkish defences on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The NZ Infantry Brigade was to be conjoined with the Australian Infantry Brigades to form an Australian & New Zealand Infantry (ANZAC) division, who together with British and French divisions, were going to drive the Ottomans from the Gallipoli Peninsula.

By March 1915, the NZ Infantry Brigade was ready to deploy. Gallipoli being no place for the use of Mounted Rifles units, the NZMR Brigade continued to train in Egypt. On April 3rd, orders were issued for the attack on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The New Zealand Infantry Brigade embarked onto transport ships, Pte. Bill Kittelty on the TS Lutzow, on 19 April and the convoy sets forth for the Gallipoli Peninsula. The troops will remain at sea whilst the final preparations are made with the Australian Division for a coordinated landing to attack the Ottomans who are entrenched and well protected in the heights above the Gallipoli beaches.

On 15 April the now re-named Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) comprising the 1st and 2nd Australian Infantry Divisions, AIF and the 1st NZ Infantry Brigade, NZEF. These joined with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF – British and French Divisions) that were positioned on Lemnos, an island some 120 km SE of Anzac Cove, and prepared for the attack.

The invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula on April 25, involved the British and French Divisions and an ANZAC Division made up of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). Lack of sufficient intelligence and knowledge of the terrain, along with a fierce Turkish resistance, hampered the success of the invasion. By mid-October, the Allied forces had suffered heavy casualties and had made little headway from their initial landing sites. Evacuation began in December 1915, and was completed early the following January.

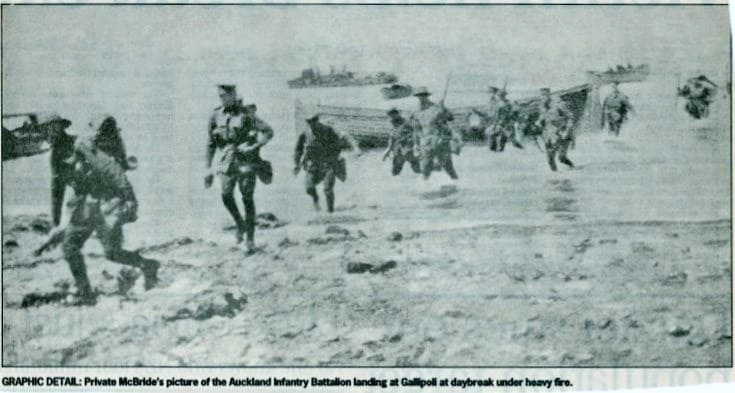

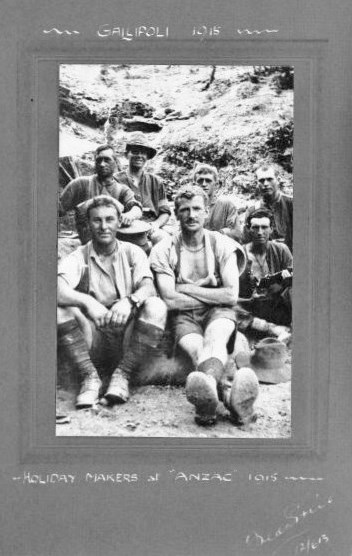

ANZAC – the Landing

The land battle for Gallipoli started early in the morning of 25 April 1915. The ANZACS were to land at various beaches along the western side of the Peninsula however things did not go well with the landings occurring in the wrong locations. Instead of gentle slopes, there were steep cliffs and the ravines.

Casualties were heavy right from the start. In the first four days of the campaign 3300 wounded passed through the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing station.

At 0415 the first wave of 36 boats of the Australian 3rd Brigade are towed by lighters toward the landing area. The destroyers carrying the second wave are moved up behind them. At about 0430 the lead Australians boats are released from the lighters and rowed towards the beaches. At 0500 the first Australian units of the ANZAC Division’s Main Force approach the shore under heavy fire from Ottoman artillery which causes many casualties. Heavy shelling came both from the heights overlooking the landing place, and from the ships, with shells falling among the transports. As the boats draw closer to within machine gun range, casualties on the boats occur. Strong currents meant the boats landed adrift of their planned landing area and were scattered all along the shore. The men had to regroup on the shore under incessant fire before advancing on their first objectives, some successful, most not.

It is 1000-1030 hours before the Australian & NZ Divisional HQ came ashore and was established on the beach. This was followed at 1100 hours by the first men of the Auckland Infantry Battalion (including Pte. Kittelty) and half of the Canterbury Infantry Battalion, coming ashore. They made for Walkers Ridge and then had to cross the 100 meters of open, flat ground across Plugge’s Plateau before descending into the relative safety of Shrapnel Valley. Snipers have a field day in the broad daylight as the men are exposed crossing the Plateau – one of the many casualties is Pte. Bill Kittelty.

The Ottoman fire is withering – a continual hail of lead and exploding artillery shells is reigned upon the ANZACs as they fight for a foot hold on the Peninsula. The waters edge of Anzac Cove is red with blood out to 20 meters from the shore. Bodies bob around in the lapping tide and are strewn over the beach while courageous field ambulance medics and stretcher bearers dash about like men possessed trying to administer aid and retrieve wounded as quickly as a lull in the enemy’s fire will allow.

By 1400 hours on the 25th the narrow beach itself is crowded with the dead and wounded, including Bill Kittelty who after a long wait in the hot sun, is carried back to the beach after dark for treatment.

It is 1600 hours before the Otago Infantry Regiment and the other half of the Canterbury’s are landed. At midnight a meeting of the on-site commanders is held to review the days progress and horrific casualty tally. Their meeting results in a unanimous request of the C-in-C, Lt. General Sir Ian Hamilton, to evacuate the Peninsular – Hamilton refuses, telling the ANZACs to remain, hold what gains they have made, and dig in!

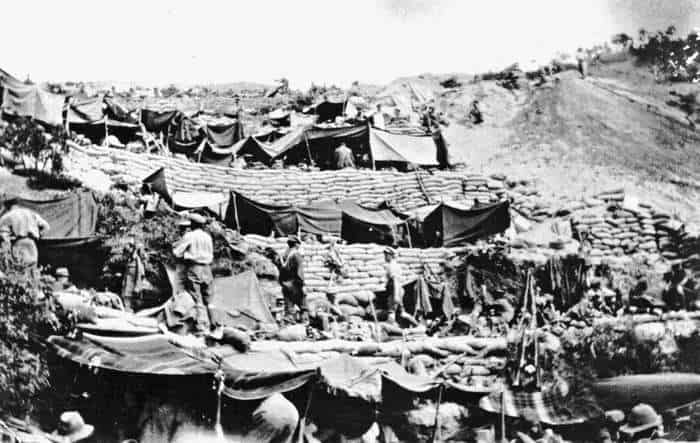

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Ottomans were dug on the heights above the landing area. The ANZACs were inadvertently jammed on the one very small breach at Anzac Cove and were very exposed almost every time they moved, affording Ottoman snipers and artillery opportunities to increase what was becoming a dreadful death toll. The maelstrom of Ottoman shot and shell continued to rain down on the ANZACs most of the day whilst the scramble uphill towards planned objectives was continually thwarted by Ottoman fire and the steepness of the terrain. By 2300 hours that night, 153 Kiwis are dead, 100 of these are from the Auckland Infantry Battalion and more would die from mortal wounds received on this day.

Evacuation

It is nightfall before Pte. Bill Kittelty was recovered from Plugge’s Plateau, the daylight hours being too dangerous for the stretcher bearers to venture across open ground. He is alive but his right forearm is shattered by a gunshot wound (GSW) together with some of his fingers – he had also lost a lot of blood. Stretcher bearers evacuated him to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station on the beach however the sheer number of casualties meant it was some time before his wounds were assessed by a surgeon and dressed. Casualties had been evacuated by barge from the beach to a hospital ship or transport ship during the day, often the targets of enemy fire. All the ships were filled with wounded (including Pte. Kittelty) by the end of the first night. Bill’s transport reached Egypt on 30 April and on arrival, Pte. Kittelty was admitted to No.15 General Hospital in Alexandria – at least he was alive!

Following his initial treatment at 15 GH Pte. Kittelty was released to No.17 General Convalescent Hospital at Mustapha on the 1st of May. He was returned to the NZ Advanced Base at Zeitoun on 22 May and prepared to return to the battalion on Gallipoli, being declared fit for duty. Pte. Kittelty entrained for Alexandria and embarked on HMT Novian on 26 May along with other returning and reinforcement personnel, and arrived back at his unit on Gallipoli on the 1st of June.

August Offensive, 1915

For the next two months the ANZACs made repeated attempts to dislodge the Ottomans with limited success only. The British Allied commander on the peninsula, Sir Ian Hamilton, devised grand plans for the August Offensive on Gallipoli, a ‘breakout’ offensive by the combined forces of Australia, New Zealand (including the recently arrived NZ Native (Maori) Contingent), Britain and India.

NZ Military historian Richard Stowers summarised the events surrounding New Zealand’s part in the August Offensive on Gallipoli with a 2015 article published in the Sunday Star-Times, an excerpt of which is reproduced below:

“It was to begin after dark on the evening of 6 August 1915, and Hamilton wanted the ANZACs to cut a swathe straight across the Peninsula in the direction of Maidos village (Eceabat) alongside the Narrows. He still believed that once the Dardanelles’ western foreshore was controlled, the British and French navies would be able to continue their push towards Constantinople (Istanbul).

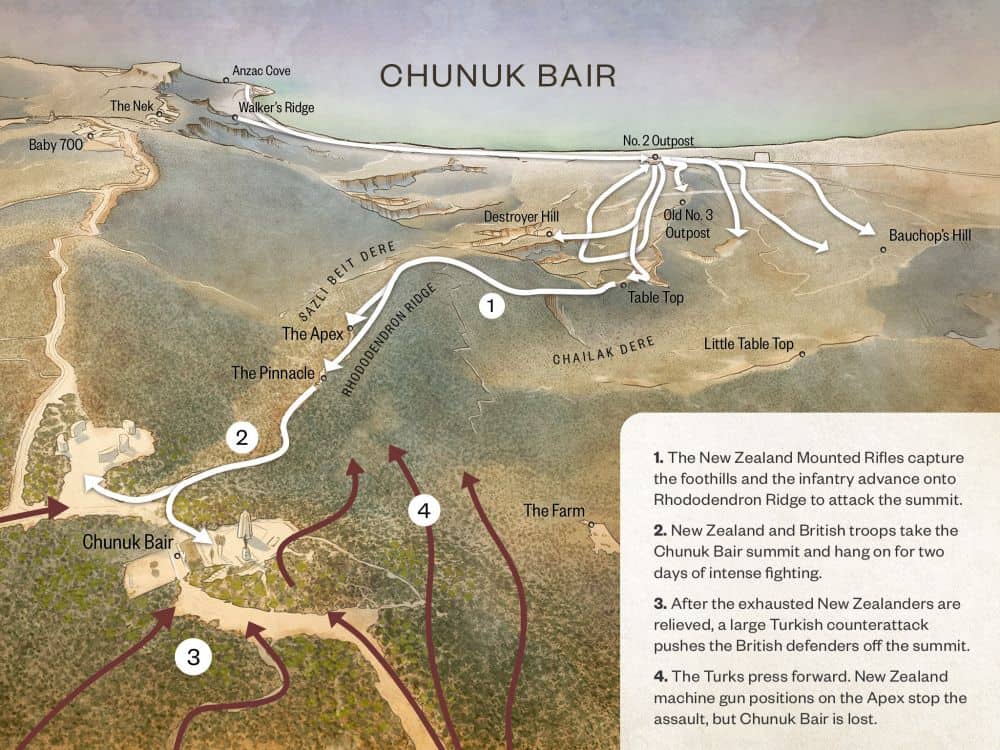

After gathering valuable intelligence during June and July, the ANZAC commanders latched on to a strategy that they knew would be difficult: to push a large body of troops into the northern valleys that led to Chunuk Bair, a high point on the Sari Bair Ridge. From the ridge they could turn to the south and come down behind the Turkish trenches surrounding the present Anzac sector.

It became clear to Hamilton and his command that the only possibility of the operation being a success was to simultaneously start a third landing on the peninsula that could quickly link up with the Anzac Sector. So Command looked to the north and settled on Suvla Bay, less than five miles from Anzac Cove and only lightly defended. Here, a strong force of British troops would land unopposed on 7 August.

The route the New Zealanders would take during the offensive resembled a clockwise half circle. They would start from No. 2 Outpost through three roughly converging gullies separated by adjacent ridges, slowly swinging to the right and east towards Rhododendron Spur/Ridge and Chunuk Bair, then turn further right and south towards Battleship Hill and Baby 700. Once the heights had been taken, their second objective was to release the Turkish stranglehold along the northeast perimeter of Anzac. Then a major Allied thrust towards the Dardanelles would break out through the more accessible northeast perimeter.

That was the theory, but in practice the plan bogged down in the approach to the Sari Bair Ridge and eventually collapsed on the summit of Chunuk Bair.

The first action of the August Offensive was the costly diversionary attack at Lone Pine by the Australians at 5.30PM on 6 August. Their casualties in the attack and over the first two days’ defence amounted to over 1,700. The irony of the attack was that one of its objectives – to draw Turkish troops to the location and away from Northern Anzac – was not achieved. In a cruel twist of fate, reserve Turkish troops sent to the area in response, happened to be placed near Chunuk Bair when the New Zealanders later took the summit.

‘Apex’ and ‘The Pinnacle’

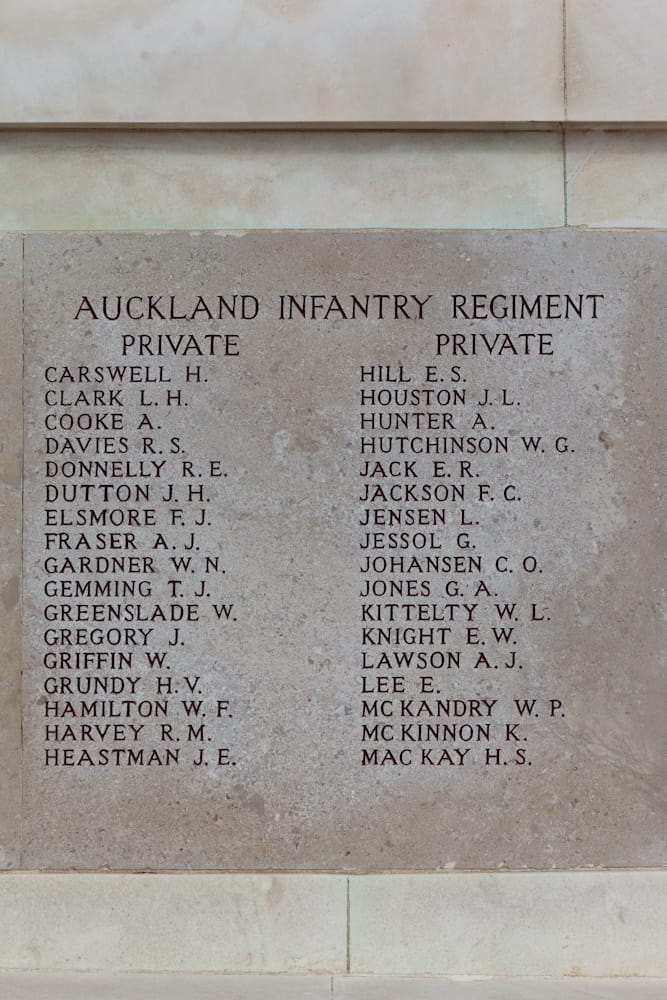

Late on August 6th, the combined force of three NZ battalions marched out of Anzac Cove with the goal of taking the strategically significant peak known as Chunuk Bair. As planned, the New Zealanders commenced their offensive by setting out after dark on 6 August. The NZ Mounted Rifles had been tasked with re-taking strong points the Ottoman’s had seized including Old No.3 Outpost, Table Top and Bauchop’s Hill, which they did over the ensuing 48 hours, with tolerable casualties. The infantry, after a night of tough climbing on the 7th of August, seized the APEX. In the face of overwhelming fire, the Auckland Battalion pushed forward to take the Pinnacle, the final obstacle just short of their objective, Chunuk Bair. The battle was furious and costly on both sides, the A.I.B. being briefly successful in occupying the vacated Ottoman trench line on the Pinnacle. In the battle to take the Pinnacle, some 227 New Zealand lives were lost, including 78 from the Auckland Bn, 75 from Canterbury and 46 from Otago.

In the midst of the battle, the Wellington Battalion Commander, Lieutenant Colonel William Malone refused to send his men to their slaughter and resolved to try and take Chunuk Bair at night.

The night’s efforts would become the most successful operation for the New Zealanders on Gallipoli, and would eventually prove to be the most successful Allied offensive operation of the Gallipoli campaign.

Charles Bean, Australian war correspondent, summed up the importance of the night’s successes: “This magnificent feat of arms, the brilliance of which was never surpassed, if indeed equalled, during the campaign. But because of the rugged and mostly uncharted terrain encountered en route, the heavy equipment carried by the soldiers, and the tight, unworkable schedule, the original plan of capturing Chunuk Bair pre dawn on 7 August became an impossibility.

The ANZAC’s had experienced two tragedies on 7 August:

- Firstly, the Australian Light Horse attacked the Nek on the pretext of joining up with the New Zealanders who were meant to be moving towards the Nek from the direction of Chunuk Bair early in the morning. No one told the Australians that the New Zealanders’ thrust had stalled before Chunuk Bair at the Apex on Rhododendron Spur. At precisely 4.30AM two waves, each of 150 Australians, climbed out of their trenches and dashed across the Nek, and within seconds of each charge not a man was left standing. A third wave, and half of a fourth met a similar fate.

- Secondly, Colonel Francis Johnston, Commanding Officer of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, ludicrously ordered the Auckland Infantry Battalion to attack Chunuk Bair, a distance of about 500 yards, at 11AM. As they moved forward they were caught in a hail of bullets. They quickly learned there were Turkish machine-guns positioned on Chunuk Bair, but there could be no stopping until they got to the Pinnacle, a distance of well over 100 yards. Within seconds, the Auckland Battalion lost over 60 men killed, one of whom was Pte. Bill Kittelty.

With the New Zealanders consolidated their position behind the Apex during the afternoon of the 7th, the final assault of Chunuk Bair commenced pre-dawn on the following day, August 8th, initiated with a naval barrage that had virtually cleared Chunuk Bair of the Ottomans. Led by their Commanding Officer Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone, the Wellington Infantry Battalion surprisingly took the summit virtually unopposed and immediately commenced to dig in.

However, Chunuk Bair was difficult to defend and it wasn’t long before the Ottomans were on the counter attack by 5.AM, intensifying their charges as reinforcements arrived. Turkish artillery soon bombarded the summit from at least two directions. Four New Zealand units fought to hold. As well as the Wellington Infantry Battalion, there were the Auckland Mounted Rifles, Otago Infantry Battalion, and Wellington Mounted Rifles, in order of their arrival on the summit. A day of fierce fighting followed with a total of 424 New Zealand lives lost. The Wellington Infantry Battalion – spared from the heaviest fatalities the day before – lost 296 men in a single day. It was by far the worst day of the Gallipoli campaign for New Zealand fatalities.

Probably the fiercest and most desperate fighting of the whole Gallipoli campaign took place on the summit of Chunuk Bair over the two days the position was held by the New Zealanders. After two days and nights of bitter fighting, the New Zealanders finally vacated the summit of Chunuk Bair on the night of 9 August, being relieved by two British infantry regiments who were quickly overrun by a massed Turkish attack early the following morning. The summit then remained under Turkish control for the remainder of the campaign while the New Zealanders formed a fortified line at the Apex.

Charles Bean was present when the remains of the Wellington Infantry reported to Headquarters after coming off Chunuk Bair: “Of the 760 of the Wellington Infantry Battalion who had captured the heights that morning, there came out only 70 unwounded or slightly wounded men. Throughout that day not one had dreamed of leaving his post. Their uniforms were torn, their knees broken. They had no water since the morning; they could only talk in whispers; their eyes were sunken; their knees trembled; some broke down and cried like children.”

The Auckland Mounted Rifles suffered a similar fate. Of the nearly 288 Auckland Battalion men that advanced on the summit, only 22 remained.

Over the two days on Chunuk Bair, New Zealand suffered nearly 2500 casualties, including over 800 dead. Over the five days of the August Offensive, 6-10 August, over 880 New Zealanders were killed and close to 2,500 wounded. By unit, the Auckland Infantry Battalion lost 100 dead, the Wellington Infantry Battalion 313, Canterbury Infantry Battalion 93, Otago Infantry Battalion 124, Auckland Mounted Rifles 90, Wellington Mounted Rifles 64, Canterbury Mounted Rifles 31, Otago Mounted Rifles 34, Maori Contingent 21, as well as 10 others. Only three Wellington Infantry deaths out of the 313, were recorded as dying of wounds, indicating that many wounded men died before receiving medical attention. Source: Author, Richard Stowers.

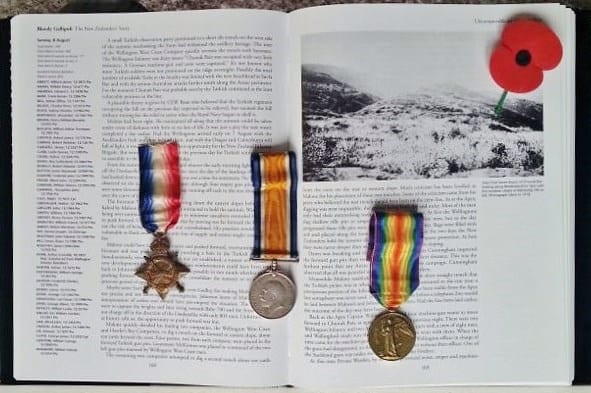

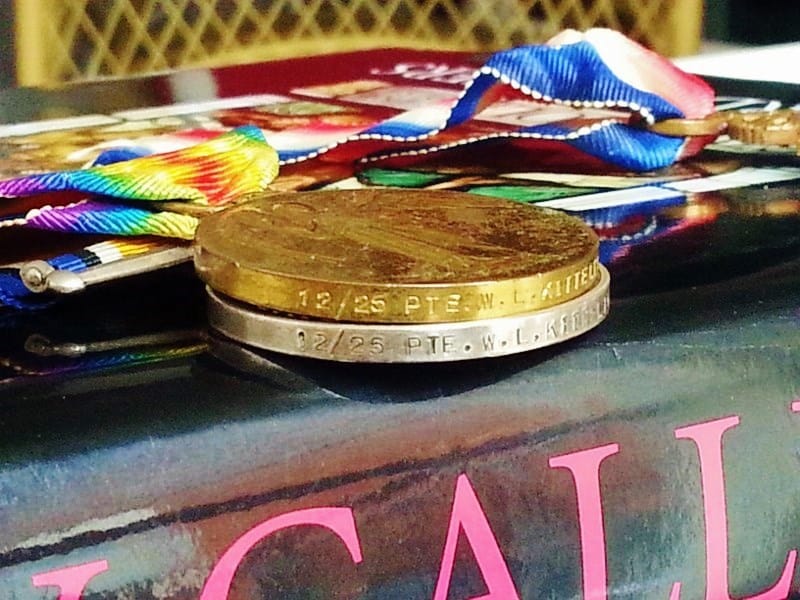

Pte. Bill Kittely was awarded three medals for his service. In addition to the medals, between 1921-1922 his mother Esther Kittelty received a commemorative Memorial (‘Death’) Plaque and Scroll to commemorate her son’s service and sacrifice. The ANZAC Gallipoli Commemorative Medallion was made available to survivors and descendants in 1967, the 5oth Anniversary of the Landings.

Awards: 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18, Victory Medal; Wound Stripe x 1; Memorial Plaque & Scroll, ANZAC (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion (1967)

Service Overseas: 273 days (9 mths+)

Total NZEF Service: 313 days (10 mths+)

Note: ** 22/136 Sister Mabel Eliza Jane KITTELTY – Territorial Force, NZ Army Nursing Service (NZANS) Corps & Red Cross VAD. Mabel had been working as a private nurse in Greymouth when she, her mother Esther and sisters Daisy and May, moved to Auckland in 1913. Mabel had joined the Red Cross Volunteer Aid Detachment and continued private nursing. With the onset of war, the Red Cross had offered to train and provide Volunteer Aid Detachment personnel to supplement medical service staff in England, Egypt and France.

Mabel followed her brother Bill’s lead and enlisted in the territorial army nursing service on 6 July 1915 at the age of 35. Her first active service posting as a Staff Nurse in July 1915 was to the HMNZ Hospital Ship No.1 Maheno. Service at 15 General Hospital in Alexandria followed in March 1916, a period at Suez in 1917, back to Cairo to 27 and 17 Gen. Hospitals from Mar-Jul 1917, in Oct 1917 Mabel was herself admitted with Dysentery. On 28 Dec 1917 Staff Nurse Kittelty was detached to Suez and embarked SS Tofua to return to NZ. Back in NZ Mabel continued to serve and was promoted to the rank of Sister. Mabel married Auckland farmer, Percy James NORTH in 1919 and later lived at Oteroa, Kaeo in Northland. Sister Mabel North was discharged from the NZANS on 15 January 1920. Mabel lived a long and productive life – she died on 24 Jun 1969, aged 98.

Awards: 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18, Victory Medal; NZ Army Nursing Service badge

Service Overseas: 3 years 286 days

Total NZEF Service: 4 years 194 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Out of the blue … or ‘divine’ intervention?

In April 2015, the RSA Review newspaper ran a request in the “Lost Trails” column from Phillipa seeking the medals of William Kittelty. As is my practice, I recorded the details by first gathering the basic data from the AWMM Cenotaph site and placed it on the Medals~MISSING page of the MRNZ website, in the hope the requests will be seen and offered up. I noted that Phillipa had posted a similar request message for the missing medals on her great uncle Bill and great aunt Mabel’s Centotaph profile pages.

A couple of weeks after the Lomas article had gone to print in April, I caught it some weeks later on the Stuff website. Regrettably, Phillipa did not receive any responses from either sources and so she left the matter in abeyance.

In August 2019 I received an email from a North Island collector requesting information about the Kittelty medals he had seen advertised on our Medals~MISSING page, specifically had they been stolen? The title of the page is “Medals~MISSING … LOST–MISSING–STOLEN.” After checking on the listing, yes the medals were listed as missing however were not known to have been stolen – a misinterpretation of the page title.

My correspondent was delighted to learn they had not been stolen when I responded to him later in the day, as he had owned them for over a year. We discussed whether he was amenable to the possibility of reuniting the medals with the family, as interest had been expressed. After giving my proposal some thought, the owner emailed me back again (same day) saying he was … AND … as if by some mystical quirk of fate, the owner pointed out that we were by coincidence corresponding on this issue on the 8th of August 2019 – exactly 104 years to the day that Rifleman William Leslie Kittelty was killed assaulting The Pinnacle on the Gallipoli Peninsula!

I immediately contacted Phillipa who could not believe the medals had been found. Once I had personally checked them for authenticity, cleaned and packaged them, they were air freighted to Australia. Phillipa phoned me the day they arrived in her hands, just four days after leaving Nelson. Mabel Kittelty’s medals are the next on Phillipa’s list – if anyone can offer information as to their whereabouts, I would very much like to hear from you.

The reunited medal tally is now 303.

‘Lest We Forget’