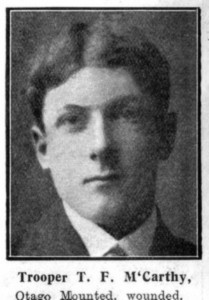

9/732 ~ THOMAS FREDERICK McCARTHY

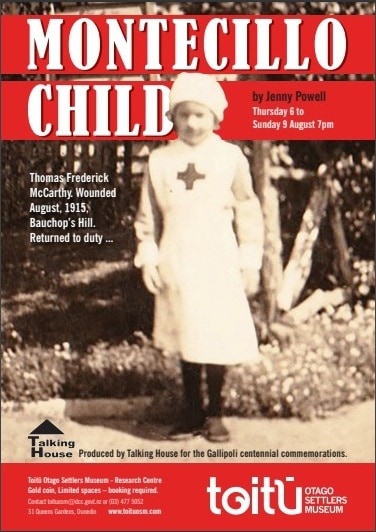

As part of the commemorative tribute Jenny assembled a display of mementos and souvenirs that special significance in the Toitu Otago Settler’s Museum. These recalled both her grandfather’s and others who had served at Gallipoli including those who did not return. An NZEF Discharge Certificate, a hospital identity tag and a commemorative Anzac (Gallipoli) Medallion where among relics of Tom McCarthy’s service on the Peninsula. A Gallipoli Star awarded to Ottoman soldiers sat beside a Memorial Plaque, a notebook and pay book, and the 1914/15 Star of an Otago Signaller who had been killed in action at Gallipoli. Souvenir hunting was and is a typical soldier past-time, this being also represented in the display by an Ottoman water canteen, the fuse head of a bomb and an Ottoman soldier’s pipe.

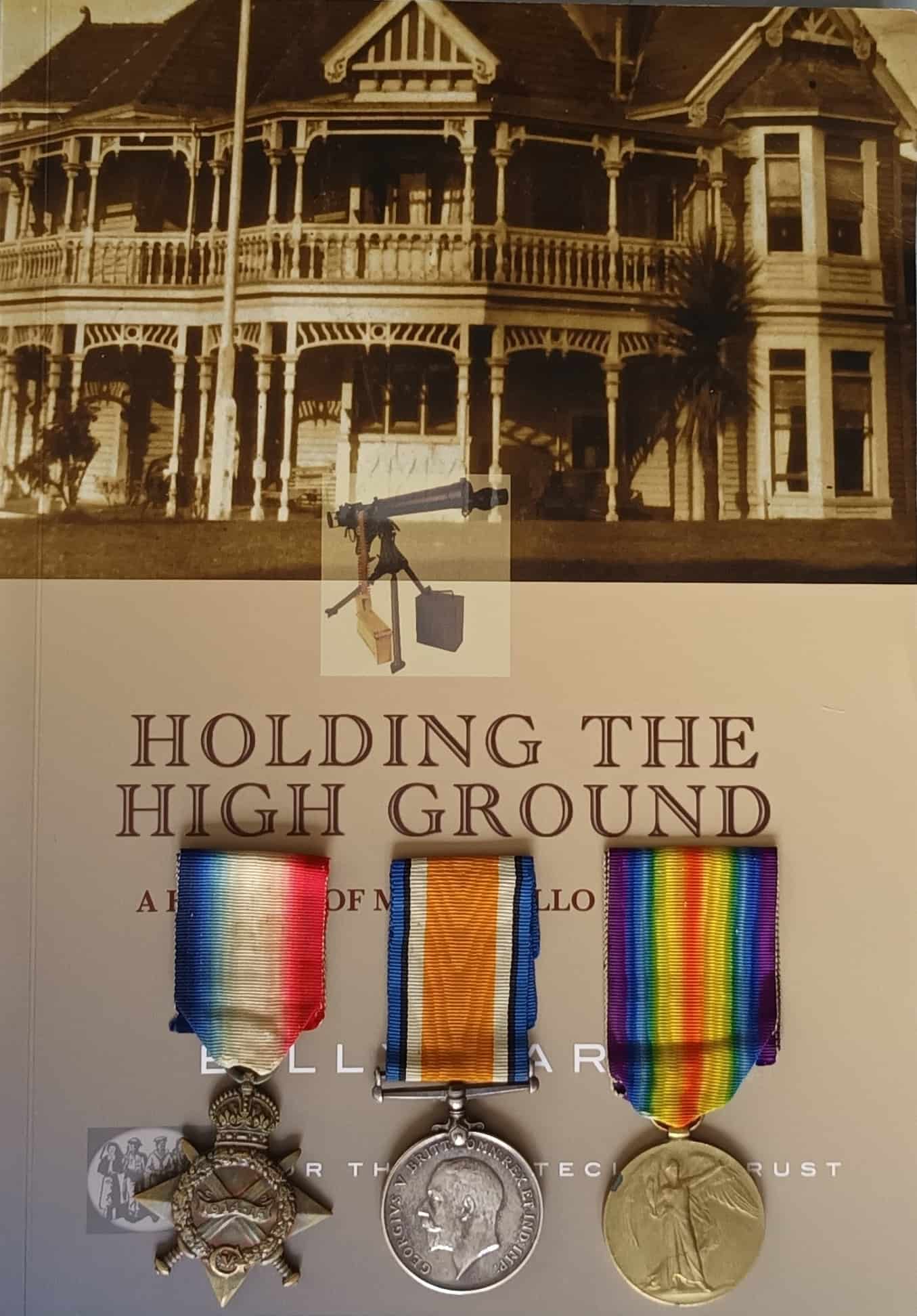

Jenny’s involvement both in the collaborative project and relic display had prompted her to contact MRNZ in 2014 in an attempt to find her grandfather’s missing medals. Jenny could never recall seeing the three medals her grandfather had received and so had absolutely no idea where they might be, or when/how they became disconnected from the family. The best I could do under the circumstances was to list the medals as lost/missing on the MRNZ website, and hope for the best – a shot in the dark so to speak. In the intervening years, nothing had come to my attention regarding their whereabouts. The reason why this had been so was made clear to me early in January this year.

War medals turn up

I received an anonymous phone call advising me that a ‘friend’ of the caller was in possession of Tom McCarthy’s medals and was prepared to surrender these provide they would be returned only to a family member. The owner had spotted the missing McCarthy medals listed on the MRNZ’s Medals~LOST+MISSING website page, proving once again its use as a facility for advertising missing medals being sought by descendant families. I was able to assure the caller that all medals listed on the website were the result of requests from proven descendants, i.e. the descendant’s identity and genealogical connection to the medal recipient had been proven to my satisfaction, before the medals were listing.

The medal owner had indicated that the McCarthy medals were obtained at auction more than 20 years ago and that he was now at a time in his life when he wished to see them returned to the rightful family. We have had a number of similar requests over the years and in managing these, I have found it essential to preserve the anonymity and privacy of both donor and descendant so that both parties can have confidence in MRNZ’s confidentiality plus balanced and impartial advocacy for both. As most people do not have a thorough understanding of medals and the traps that the unknowing can fall into when offered medals, I am able to apprise each party of specific information that ensures the interests of each are served equally and that each may make informed decisions.

Imagine Jenny’s reaction when I telephoned her almost nine years after she lodged her missing medals request, to tell her that they had surfaced!

Early days in Christchurch

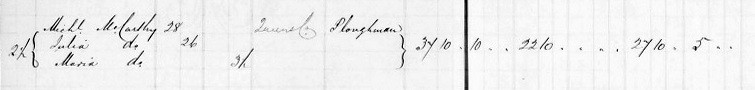

Thomas McCarthy’s family had their origins in Ireland. Michael Joseph McCarthy was 28, a Ploughman from Loughmoe, Killanigan in County Tipperary when he and his 26 year old wife, Julia (nee Scully) of Portarlington & Offaly in County Laois, and their three and a half year old daughter Maria, embarked onto the

The Clontarf voyage to NZ had taken 107 days, reaching Port Cooper (Lyttelton) on March 16, 1860. After their arrival the McCarthys traversed the Bridle Track over the Cashmere Hills on foot to undergo quarantine in the immigration barracks at Addington before eventually settling south of Christchurch at what is now Templeton.

Michael McCarthy began farming with land allocated to him by government ballot, part of his land being where the Riccarton Racecourse is now situated. The McCarthy’s first New Zealand born child Catherine was born at Leeston in Dec 1861 however she died after only four short months of life. The first born son was named after his father – Michael McCarthy [Jnr] was born in Christchurch in 1865 followed by Elizabeth (1867) at Leeston, Augustine Frederick (1869) at Papakaio, Peebles near Oamaru. Later came Agnes Julia (McCarthy) KIRBY (1871), Charlotte Josephine (McCarthy) DOWNIE (1874) and John McCarthy (1910-1910) who were all born south of Dunedin at Chain Hills, Taieri.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

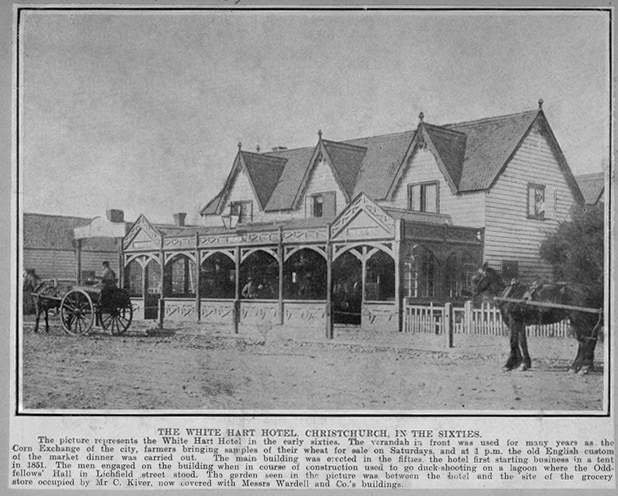

The Templeton farmland became a valuable asset for the McCarthy’s. Julia being a well educated woman (who spoke fluent French) was rather haughty but strict in the way the business of the farm was managed but, unfortunately not strict enough to control Michael’s penchant for gambling. It was undeniable that Michael had worked hard and added value to the farm however his gambling at the White Heart Inn in Christchurch was the source of his undoing.

The first permanent “White Heart Inn” was opened on High Street in central Christchurch in 1851 by Irishman Michael Brennan Hart. It was a two storey, wooden building with three dormers in the roof and an enclosed veranda under which a corn market was run. Sale yards were situated next to the hotel. This is the building that Michael would have known during his gambling days. In July 1852, the White Hart Inn, (later renamed the White Hart Hotel) offered accommodation and became an arrival and departure point for the Cobb and Co. stage coaches.

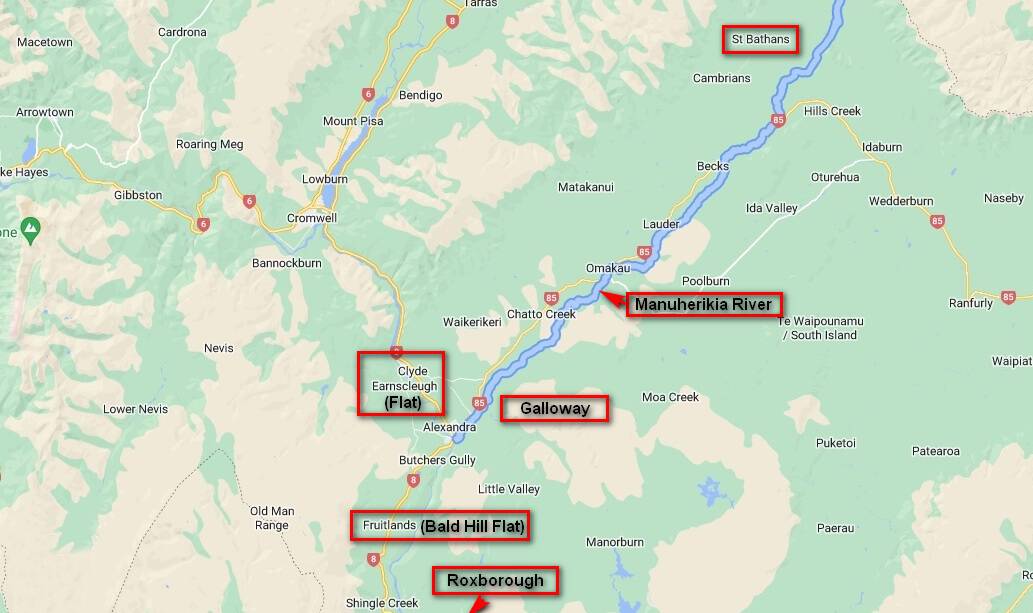

Michael’s accumulated gambling debts at the Brennan establishment ended up costing him dearly. He had to sell the Templeton property to pay off his debts. The McCarthy’s left Templeton around 1866 and progressed south over the next ten years, firstly to Leeston-Selwyn 1867, Oamaru 1869, Wyndham 1887 and by 1889 had arrived in the Manuherikia River valley in Central Otago, settling near Galloway. The river valley (now part of the Otago Rail Trail) runs from the ranges north of St Bathans down to Alexandra where it joins the Clutha (then the Molyneux) River.

Michael McCarthy [Jnr] whom everyone knew as “Mick” joined with many others who had arrived before him to make a living from the work associated with extraction of the alluvial gold, first discovered in the Molyneux (Clutha) River in August 1863. In Feb 1891, Mick McCarthy married Sarah FIELD (1869-1903), a young lady from Blackstone Hill near St Bathans. Sarah was the daughter of Sussex immigrant George Upton FIELD of Rumboldswhyke, Chichester and his Hobart, Tasmanian born wife Mary Ann WAYMAN (1845-1898). Mary Ann’s parents, Morayshire born mother Catherine Nairn and Berkshire born father John Wayman, had been ‘transported’ to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), he for 14 years in 1833 on the Stakesby for house-breaking, and she, together with a sister and neice, for 11 years in 1839 on the Hindostan for sheep-stealing!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

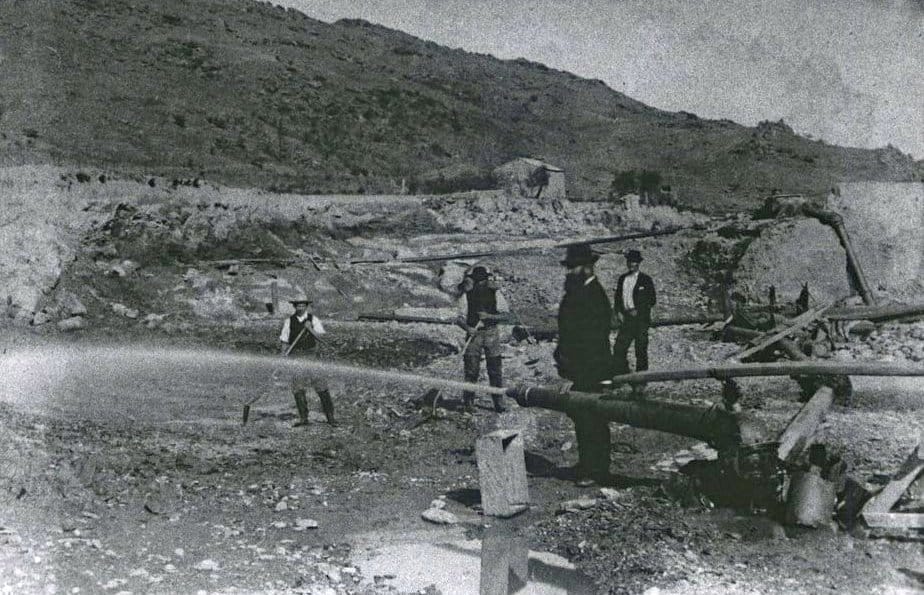

Bald Hill Flat & Earnscleugh

Mick and Sarah’s first child was a son, George Michael McCarthy (1893) born at Alexandra while their second son, Thomas Frederick McCarthy was born 28 May, 1894 at Galloway in the Manukerikia River valley, six kilometres north of Alexandra. Following Thomas’s birth Mick began work as a labourer at Bald Hill Flat** in the Teviot Valley, some 14 kilometers south of Alexandra, and moved his family there. It wasn’t long before Mick began work as a gold miner at a sluicing operation on the banks of the Molyneux (Clutha) River.

During this time Mick and Sarah’s attempts to increase their family at Bald Hill Flat unfortunately had met with bitter-sweet success. Their third child and first daughter, Agnes Berth McCARTHY (1895) died after only two weeks of life. A healthy boy, Edmund Francis “Ted” McCARTHY (1896-1972) was to be the only bright spot as the next two babies, Mary Bertha (1898) and Cornelius McCarthy (1902) died within weeks of their birth.

The McCarthy boys – George, Tom and Ted – started their schooling at Bald Hill Flat, Tom starting around 1900. About 1902 the McCarthy’s moved north-west towards Clyde to settle at Earnscleugh Flat where Mick McCarthy joined one of his brothers working on a gold dredge, one of 187 that were operating in between Clyde and Roxborough by 1900.

Earnscleugh Flat embraced an area that extended north-west from Alexandra, along the south bank of the Molyneux towards Clyde. A bustling settlement of miners and farmers, Earnscleugh boasted a school the McCarthy boys attended, a post office and a Catholic church for its large population of Irish immigrant miners and families including the McCarthy’s. Sheep and crop farming was well established in the valley together with a fledgling orchard industry for which the area would eventually become famous. That however was not without disaster occasioned by severe winter weather that Central Otago is renowned for.

While Mick McCarthy continued to work, George, Tom and Ted whilst at school were still in need of a mother. The boys were taken in by Mick’s sister-in-law, Bertha Field McGinnis (1872-1938) and her farmer husband Michael Patrick McGinnis, also known as “Mick” – confusing in an Irish community? Bertha’s maiden name was FIELD, she being the younger sister of the boy’s mother Sarah McCarthy.

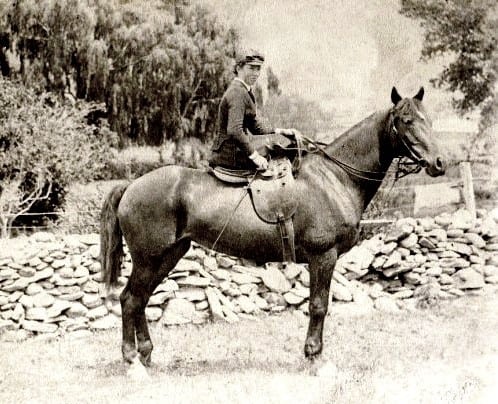

Born in the Ida Valley, Bertha Field was renowned as woman who knew her horse flesh and a very capable rider. She was the first female jockey in the area and rode side-saddle (see photo) with eleven pounds of lead sewn into the saddle flaps to bring her up to the required weight. Bertha predominantly rode hacks (Hackneys) which she also bred, and competed very successfully in riding and horse presentation events at the annual Otago A & P shows. She also trained her husband’s ploughing horses, Mick McGinnis being a regular competitor in local ploughing competitions. Bertha’s father, George Upton Field, was also known to be a fine horseman and was easily recognised in the district with his distinctive coloured horse and trap.

Whilst having experienced their own tragedy of losing children with the death of their first two daughters at birth (1897 and 1900), Bertha and Mick fortunately were blessed with a hail and hearty son in 1901, Albert James McGinnis. “Grandma McGinnis” as the McCarthy boy’s knew Bertha, welcomed them into their home in 1903, the boy’s remaining with the McGinnis’s until of working age. Labouring and farm work was the path all the McCarthy boys followed for their first paid work.

Note: In 1915 Earnscleugh Flat was re-named “Fruitlands” in recognition of it becoming a fruit growing area. The establishment of orchards however turned out to be abortive when only one crop of fruit was ever exported, and although there was ample summer irrigation water available, the hard winter frosts destroyed most of the trees. The project was closed down in 1926 and the settlement dissolved. Fruitlands today is a collection of modern farm houses, and the remains of a few miners’ stone cottages; some derelict, others restored. The best examples of restored buildings are John Mitchell’s cottage, and the Spear Grass Inn, formerly known as the Speargrass Hotel.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Britain declares war

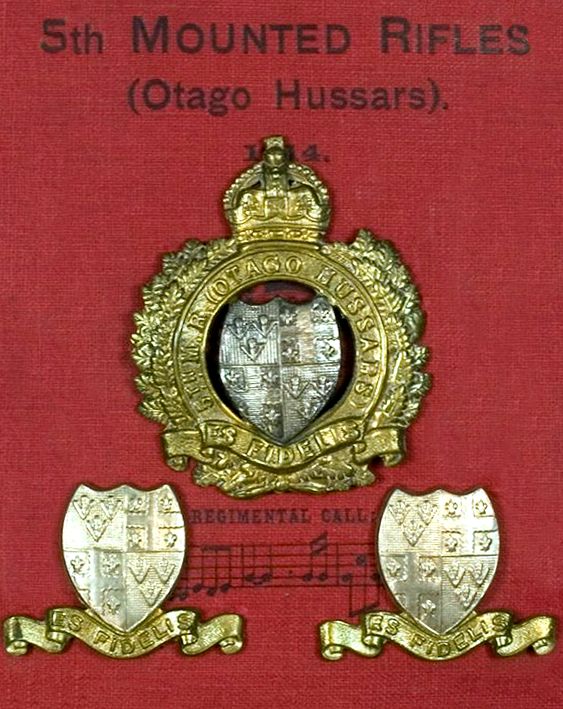

Prior to the beginning of the First World War, Tom had succeeded in landing a job as a Clerk for the government Public Works Department (later known as the Ministry of Works) in Alexandra. Talk of war and the prospect for travel and experiences abroad excited Tom as it did many young men of his age in Otago and throughout the country. When volunteers were called for to fill the ranks of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, Tom presented himself to the Drill Hall in Alexandra without delay where he was signed up with the 5th (Otago Hussars) Company, a new territorial mounted rifles unit that had been formed in 1911.

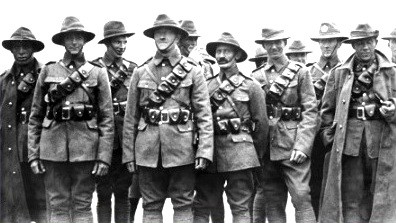

The NZ government was committed to providing a three regiment Mounted Rifle Brigade and a four battalion Infantry Brigade which together comprised the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). The New Zealand Mounted Rifles (NZMR) Brigade comprised around 22% of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and numbered 1680 men, divided between the Auckland, Canterbury, and Wellington regiments of around 550 men each. The Otago Mounted Rifles (OMR) Regiment, a separate independent unit, was also sent however did not for part of the NZMR Brigade. The OMR consisted of three squadrons, the 5th MR (Otago Hussars) Squadron, 7th MR (Southland) Squadron, and 12th MR (Otago) Squadron. The Infantry Brigade numbered about 4000, with each of the four military districts (Auck, Wgtn, Cant, Otago) each raising a 1000 man battalion.

Training & embarkation

The volunteers were encouraged to take their own horses however Tom was without one. A capable horseman and with a reasonably sharp eye with the rifle during training, the lack of a horse was no impediment to his being accepted. He subsequently flew through his Army medical inspection with a locally Army accredited doctor in Alexandra.

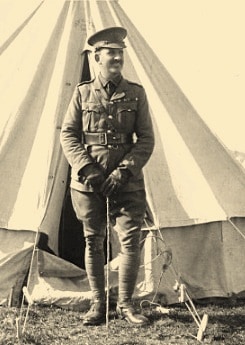

9/732 Trooper Thomas Frederick McCarthy (20) was attested for military service at Trentham on 20 October 1914 with his fellow members of the 5th MR (Otago Hussars) Squadron were to be part of the 2nd Reinforcements. After some rudimentary training, long rides on horseback, rifle range work and mounted formation rehearsals, the troopers prepared themselves for the sea voyage. Men and horses of the 2nd Reinforcements were embarked at Wellington on 13 Dec 1914 aboard one of three ships: HMNZTs 13 Verdala, 14 Willochra and 15 Knight of the Garter.

Next day, 14 December 1914, the three transports left Wellington for Western Australia and then on to Suez, Egypt carrying the Main Body of the . They steamed north through Canal into the Mediterranean Sea and on to the port at Alexandria. The New Zealand ships landed men and horses at on 28 Jan 1915 and then entrained for Cairo, 180kms south of the port. The NZ Depot Training Depot was based north of the city at Zeitoun which would be home for the NZ Mounted and Infantry Brigades. The mounted units trained in the surrounding desert for operations against the Ottoman Empire, which was expected to be fought in similar terrain.

After the failure of the Anglo-French naval assault at the Dardanelles in February–March 1915, the New Zealanders joined the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) which was hastily cobbled together in the belief the Ottomans would not commit to defend their homeland with any substantial intensity – how wrong this assumption was!

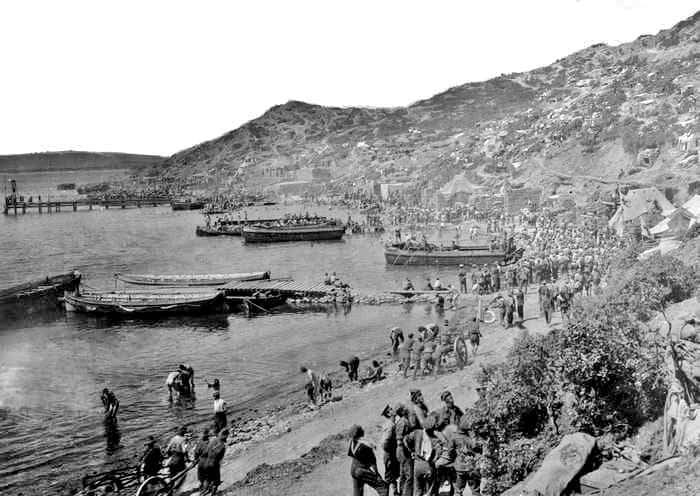

Gallipoli Reinforcements

The landings at Gallipoli from 25 April 1915 onwards were a disaster from the outset. Landing in the wrong places and under heavy enemy fire produced instant casualties among the ANZACs on a grand scale. Confusion reigned on the beach at Anzac Cove where Australian and New Zealanders were mixed together in complete state of disarray. All the while units were attempting to push up the steep slopes to make some inroads towards the enemy positions, but with little success. Down at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula where the British regiments were also were taking a hammering as they tried to land at Cape Helles. The French Corps Expeditionnaire d’Orient (Oriental Expeditionary Force) fared little better after joining the English the following day on 26th – another disaster in mass casualties!

The decision on May 5th to take the New Zealand Infantry Brigade and the 2nd Australian Brigade out of Anzac Cove to assist the French and British in the south, to thrust towards Krithia was ill-founded. This had placed the ANZACs who were tenuously holding the frontline, under extreme pressure. Additionally, on the left flank of the line, two weak battalions of the Royal Naval Division had taken over the position the New Zealand Infantry Brigade had vacated. The staggering number of casualties within the first few weeks had left huge gaps in the ANZAC ranks.

Back in Zeitoun, the NZ Mounted Rifles Regiment troopers had been cooling their heels, greatly irked at not being involved in the initial landings on Gallipoli, however that was about to change. Both NZ and Australian Mounted Brigades were summoned to Gallipoli in mid-May however without their horses; they would be fighting as dismounted infantry!

Arriving on May 12, the ANZAC mounted reinforcements included the Auckland, Wellington and Canterbury Mounted Regiments arrived in the nick of time to repel and unexpected recently reinforced Ottoman on-slaught. The Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment meanwhile remained at Mudros. The new arrivals made their way up the goat tracks of Walkers Ridge to relieve the RN Division’s Nelson and Deal Battalions who were withdrawn to rejoin their Division at Cape Helles.

Trooper Tom McCarthy’s 5th MR (Otago Hussars) Squadron together with the remainder of the OMR Regiment, were finally brought into the battle, landing at Anzac Cove on 20 May. Immediately they found themselves thrust into the thick of the ANZAC Division’s stalled assault on the heights. The battle became one of attrition, each side making gains and losing them again to the cost of a great many lives. Plans were made, changed, re-arranged even to the point of a withdrawal from the Peninsula considered but not to be. The men dug in to the hillsides to make the best of what would be very hot, fly blown summer followed by the miseries of a freezing, sleet and snow covered winter.

Sari Bair, 6-8 Aug 1915

Tpr. McCarthy had been on the Peninsula for almost ten weeks, taking his turn in the front line trenches as the reinforcements were rotated to ensure there was a 24/7 capability to repel Ottoman attempts to drive the ANZAC’s from their trenches. With the reinforcements bolstering the front line, the OMR held their line whilst led by their popular Commanding Officer, Lt-Colonel Arthur Bauchop. Leading from the front as Bauchop was want to do, the OMR whittled away at the enemy, gradually taking control of the northernmost outposts through the summer of 1915.

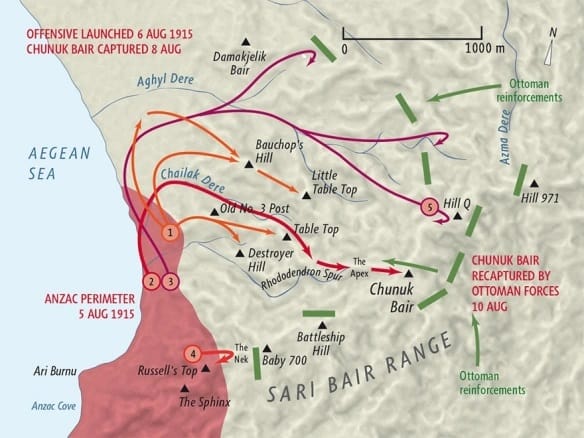

The ANZAC command had planned a major offensive for the first week of August with the aim of driving the Ottomans from their commanding and deadly position along the summit of Chunuk Bair. The attack on Chunuk Bair was to be a diversion for the Australian Division’s attempt to take the feature known as Lone Pine. The Otago MRs and Infantry were to mount a two pronged attack; the Infantry on the right would make their way up Rhododendron Spur (ridge) on route to the Chunuk Bair feature. The OMRs were to go left to clear the hill that was named in their commander’s honour – Bauchop’s Hill. The night attack began around 2100 (9 pm) on the evening of 6 August.

Bauchop’s Hill

During the afternoon of 6 Aug, the OMRs concentrated with the Otago Infantry at Happy Valley, immediately north of Walker’s Ridge. In preparation for the attack, everybody was to travel light. The men stacked their packs in Monash Gully and uniform jackets would also be discarded in favour of short sleeves just prior to the attack commencing. Webbing equipment, rifle with fixed bayonet was all that was required. The men were hyped up and anxious to get on with the attack. Just before dark, the men sewed white patches on their backs and sleeves for identification during the attack, turning their tunics inside out so they wouldn’t show until needed. For the MRs, taking Bauchop’s Hill was their primary focus as it was critical high ground they needed to dominate to prevent counter attack from the Ottomans. The ground they would be covering was treacherous in the dark so the men were told if anyone lost touch with their section, they were to join the nearest group and push on up the hill – failure was not an option!

Lying in the low ground from about 2100 (9.00pm) on the 6th, the Otago MRs and Infantry saw the searchlight beam on the scrub from a destroyer sitting off shore and then heard the scream of the destroyer’s shells as they began to pound the Ottoman positions to ‘soften’ them up as a prelude to the ground attack.

At 2130 hours (9.30pm) the search light blacked out and the Mounted Rifles began their move towards the lower reaches of Bauchop’s Hill. The OMRs would have to traverse a flat area of ground before starting the climb, going via Wilson’s Knob and then upwards clearing Ottoman trenches posts on the relatively lightly defended northern approaches with ‘bayonets only’ as they went. On their left flank were the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. The OMR Dunedin squadron (5th Otago Hussars) were to go up the southern spur just across from No 3 Outpost. Before they could do so a section of 50 Maori had to remove a barbed wire obstacle laid by the Ottomans at the mouth of the valley. This led to a skirmish with a party of Ottoman troops and the OMR/Maori group was held up by heavy fire for an hour. Such hold-ups through the night were to prove critical in putting the tight timetable of the advance behind schedule. As they climbed the lower reaches of Bauchop’s Hill, many a fight between surprised Ottoman and New Zealander was fought that night in the tangled scrub. Trenches that were encountered were taken at the point of the bayonet to retain the element of surprise and disguise the position and size of the attacking New Zealanders.

After a torturous 4-5 hours of fighting with numerous as yet unknown casualties, Bauchop’s Hill was theirs! Having taken the hill the defenders waited for the inevitable Ottoman counter-attacks while at the same time started to dig their defensive trenches on the summit. As the first one came from a much larger Ottoman force, Bauchop led the defence from the front: “Let them come boys, till they show above the scrub – I’ll give the word – then five rounds rapid [fire]. Yell like hell and into them with the bayonet.” Further Ottoman attacks were seen off the same way. Bauchop remained on the hill top throughout the night encouraging his men and getting them to yell and cheer wildly at intervals to un-nerve the enemy. By 0700 (7am) on the morning of 7 August, the defences were complete with an advanced post further up the range on the Pyramid, a connecting hill to Little Table Top. Lt-Col Bauchop led his men in one final cheer.

Australian War Correspondent and author of the Gallipoli campaign, Charles Bean described the OMR attack as a “magnificent feat of arms, the brilliance of which was never surpassed, if indeed equaled, during the campaign”, their efforts had opened the way for the following infantry to advance up the valleys to the summit. Sadly, Bauchop’s elation at the success of his men was short lived. Later in the morning he was felled by a sniper’s bullet, mortally wounded being shot through the spine and died two days later.

The losses had been severe which became apparent as the grim task of accounting for the dead and attending to the wounded began. Trooper Tom McCarthy was among the latter having sustained a serious head wound. For many of the wounded, collection by the field ambulance bearers only came after a long and agonizing wait through the night and early morning.

Tpr. McCarthy was located (unlike many others who were never found) by the stretcher bearers and moved to an advanced dressing station. Bandaged and barely conscious, once down on the beach he was carried to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station (1ACCS). After assessment and treatment, here he remained until he could be transported to a hospital ship offshore.

Evacuation & treatment

At the time he was wounded, Tpr. McCarthy had been on the Gallipoli Peninsula for almost ten weeks. The Ottoman bullet that felled him had penetrated the left front of his skull at his hairline, depressing the left parietal bone leaving a depression. Although not known at the time, the bullet had separated inside his skull which although not fatal, produced severe and lasting effects. Tom was evacuated from Gallipoli to HM Hospital Ship Delta the following day, 7 August, which transported a large number of the wounded to Alexandria, a voyage that took four days.

On arrival Tpr. McCarthy was admitted to No.1 Australian General Hospital at Heliopolis and then transferred to No.3 Australian Hospital. Of all things, Tom went down with sun stroke and admitted to the 19 British General Hospital at Alexandria. On 27 August, he was packed off to a Convalescent Hospital on the Mediterranean coast at Helwan to assist recuperation. While his general condition at this stage was weak, he also trembled continuously and was to be repatriated to NZ as soon as possible. In mid September Tom was discharged back to the NZ Depot Camp at Zeitoun. His head wound however was not healing as expected by still discharging pus. This together with the onset of more persistent headaches led to his admission to the NZ General Hospital in Cairo – he was seriously ill. Tom underwent an operation to remove bullet fragments from his head wound, a particularly delicate operation that could easily have resulted in his premature death!

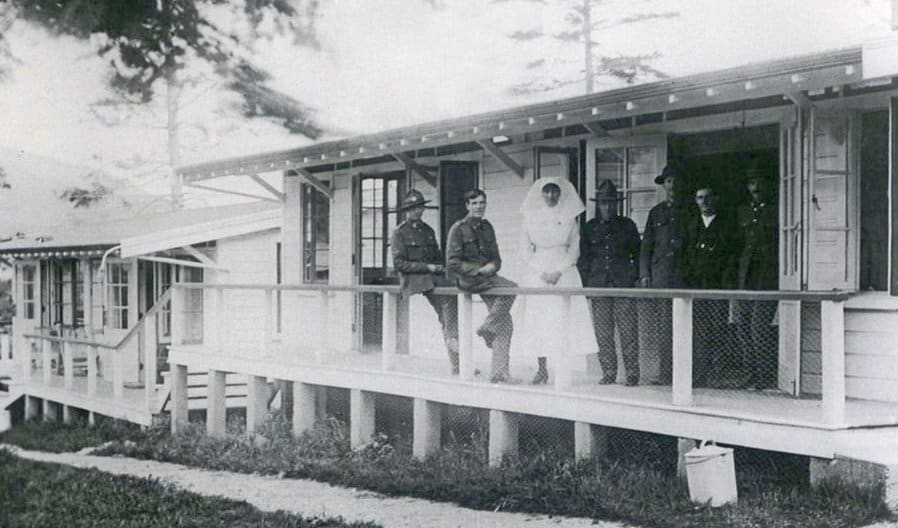

Tom survived the operation and was transferred to the Aotea Home, a New Zealand convalescent hospital in what is now the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis on 16 December 1915. The home was staffed by nurses from Wairarapa, Wellington and Whanganui and was funded by the contributions from women’s groups from Wairarapa, Whanganui and Rangitikei regions, who saw the importance of a ‘home away from home’ in the recovery of soldiers who had been wounded or fell ill during the Sinai & Palestine campaigns.

While at Aotea, Tom suffered the first of what was termed a “Traumatic Epileptic” fit while playing a hand of cards. It caused him to loose consciousness after which he shook for several days once he had come around. By January 1916, he was ‘walking wounded’ and able to do light duties. He was discharged to the NZ base at Gezriah pending his return to Zeitoun Training Camp.

In March, a second epileptic seizure resulted in Tom’s admission to the New Zealand General Hospital at Pont de Koubbeh** in Cairo. When questioned about his symptoms prior to the seizure, Tom indicated to the Medical Officer that he ‘could tell it (the seizure) was coming on’, saying he felt his head being pulled over to the right until he lost consciousness. Sadly, this began a pattern of traumatic epileptic seizures that dogged Tom for the rest of his life. Another seizure on 19 March occurred in the same manner as the last with Tom sustaining an additional self-inflicted indignity by uncontrollably biting through his tongue, an injury that took many months to heal.

After two weeks in hospital he was released back to general duties at the NZ Base at Giza (near the Pyramids) in Cairo to await his transfer to Moascar pending his repatriation with other wounded back to NZ – their war was over. Trooper McCarthy at this point was transferred out of the Otago Mounted Rifles and in to the NZ Field Artillery, his rank being temporarily altered to Gunner (Driver). This enabled him to be employed on light duties with the NZ Field Artillery element at Moascar Camp prior to the two weeks he was required to spend in the Isolation Camp before embarkation, a requirement for all soldiers arriving or leaving Egypt.

Note: ** The Egyptian Army Hospital at Pont de Koubbeh in Cairo had been offered and accepted for use by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, and was staffed by RAMC and NZMC officers, nurses and medics/orderlies.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Repatriation

When HMNZT Willochra arrived at Suez on 14 April 1916, the invalid men to be repatriated were shipped the 76 kilometers down the canal to the point of embarkation. Arriving at Port Chalmers on 28 Sep 1916, Willochra discharged over of 150 broken Gallipoli survivors, sick and wounded New Zealand soldiers along with the medical staff who had cared for them. Some of the wounds were obvious — mutilated faces or missing limbs — but wounds of the mind in both patients and carer’s alike, were concealed within: the inconceivable stress, fear and horror of war added to the anguish and apprehension of what lay ahead for them. Tom was disembarked and transported to the Military Section of Dunedin Hospital where he was registered into the veteran’s hospital system before being transferred to the Pleasant Valley Sanatorium (Plunket Ward) at Palmerston (south), 54 kilometers north of Dunedin.

The Sanatorium was opened in 1910 to accommodate suffers of Consumption (Tuberculosis -TB). In the course of Tom’s medical board assessment at Moascar before he returned to New Zealand, the Medical Officer had diagnosed him with the first stages of Phthisis, otherwise known as Pulmonary Tuberculosis. He remained as an in-patient at Pleasant Valley until the end of the year by which time he was sufficiently well enough to return home. Tom returned to Alexandra where his brother Ted lived and worked as a Rabbiter, having recently returned from France in March.**

Whilst his strength and fitness improved, Tom was still subject to the sporadic, blinding headaches accompanied by the epileptic seizures and loss of consciousness. The Army medical system could do nothing more for Tom but refer him for continued care at Clyde’s Dunstan Hospital which would be paid for by the War Pensions system. Consequently, Gunner Thomas Frederick McCarthy was discharged from the NZEF on 3rd November 1919, classified as “no longer physically fit for war service on account of wounds received in action.”

Medals: 1914/15 Star, British War Medal 1914/18, Victory Medal; Silver War Badge (SWB); Anzac (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion & Lapel Badge (1967)

Service Overseas: 1 year 167 days

Total NZEF Service: 2 years 15 days

Note: ** 60970 Private Edmund Francis “Ted” McCARTHY – 2nd Canterbury Infantry Regiment – 31 Reinforcements

At the time he enlisted, Edmund was working as a Horse Groom in Riccarton, Christchurch. He embarked for service overseas on 16 Nov 1917 and saw out the war in France until after the liberation of Le Quesnoy. Edmund served for 1 year 282 days in the NZEF. Having suffered with Trench Fever and Flat Feet, he was discharged on 22 Mar 1919 as no longer physically fit for war service. He was awarded the British War Medal 1914/18 and the Victory Medal. Edmund McCarthy died in Christchurch aged 79 in 1972.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tragedy for the McCarthy’s however did not end with Tom. Within three weeks of his discharge from the NZEF Tom and Ted’s elder brother, George Michael McCarthy died on 24 Nov 1919. Stricken with Spanish Flu, the viral epidemic that had started in the northern hemisphere and was now sweeping New Zealand, 25 year old George died in Dunstan Hospital leaving Tom, Ted and their father Mick as the sole survivors of their McCarthy family.

Tom’s headaches interspersed with the momentary losses of consciousness persisted with varying degrees of severity. The damage to his brain by the irremovable fragment of the Turkish bullet still embedded in his skull also led to a worrying development. While his cognizance and outward appearance belied what was happening inside his head, the traumatic seizures were a significant handicap to what Tom could do and where he could go. This he could manage to some degree with medication but had become the new normal for Tom McCarthy.

“Montecillo”

In Dunedin, a large private residence was identified by the Red Cross as being suitable to accommodate disabled veterans needed treatment and was successfully acquired by in 1918 with the support of the Patriotic Fund and public assistance. While treatment centers for shell-shock, consumption (TB) and orthopedic conditions were planned concurrently for Auckland and Wellington, the new 26 bed Red Cross Hospital at Montecillo was underway and opened its doors in late 1918, staffed initially by three experienced nurses who had nursed overseas during the war. As a consequence the Military Section at Dunedin Hospital was closed in July 1920, and a part-time doctor was scheduled to do the rounds at Montecillo twice a week.

The government was acutely aware of the sheer number of veterans World War 1 had produced, the temporarily damaged and the permanently broken – limbless, sightless, horrific physical disfigurement and mental trauma (shell-shock, or PTSD as we know it today) affected thousands of veterans and the facilities provided for them were often full to overflowing at times. Many of men would become long term care cases, those who would never be able to earn a living again or live a normal life as we know it.

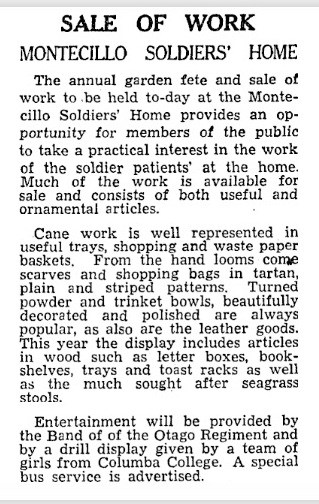

By 1925 Tom had moved to Dunedin, attending Montecillo on a part-time basis engaging in various rehabilitative treatments and activities. Veterans were encouraged to focus on practical tasks in order to alleviate their depression and focus attention. Montecillo provided opportunities for engaging in various crafts, Tom’s specialty was cane work of which he produce dozens of useful pieces of excellent quality. One of the more popular diversions were musical concerts and garden parties that became a feature of life at Montecillo, attracting local and visiting artists performing for the veterans and their families.

A ‘normal’ life ?

It was during one of these concerts that Tom was introduced by one of the female musicians, to her friend Miss Jessie KELMAN (1894-1952). Jessie was the fourth of eleven Kelman children born at Strathalbyn in South Australia by their English immigrant parents, Robert “Bob” Kelman & Ellen “Nell” Smyth. Reminiscent of a beautiful little rural English village, Strathalbyn is about 25 kilometers south of the Adelaide Hills town of Mount Barker.

But could it be that Tom and Jessie had met before? The Kelman’s had migrated to New Zealand and by 1911 had settled at South Alexandra. A number of the Kelman boys had worked on the gold dredges at the time the McCarthys lived at Earnscleugh Flat and so it is very possible the families could have become acquainted with one another through the likes of schooling, church and community activities?

Residential care

Tom had attempted to work at local labouring jobs however the pain from the neurological damage to his brain from the impact of the Ottoman bullet steadily worsened over time. The initial impact had triggered the seizures however once back in New Zealand, the seizures had grown in frequency and effectively ruled Tom’s existence. By the time Tom married, the seizures were being preceded by uncontrollable outbursts of rage. While detrimental to Tom, these also had a significant affect on his and Jessie’s ability to live any sort of a semi-normal married together. The net result was the medical authorities considered the only effective way they could to manage Tom’s epileptic seizures and accompanying rage was to keep him in permanent residential care. Accordingly Tom was admitted into full time residential care at the Montecillo Red Cross Home on 25 January 1932, thirteen years after the end of World War 1. Jessie and baby Nola initially remained at Walter Street until a house could be made available within the grounds of Montecillo.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While Jessie, Nola and their dog Paddy remained at Walter Street, Tom was still able to stay for the odd weekend on occasion however he remained fairly distant and disinclined to move far from the house. Far from ideal for this young family, but manage they did. Around 1941, two years into World War 2, Jessie and Nola moved the few hundred yards from their Walter Street address to a house at No.8 Haywood Street, directly behind the Montecillo Home . No.8 enabled mutual access by Tom and Nola to one another on a regular basis whilst still in close proximity to facilities and medical supervision.

The veterans at Monticello were encouraged to busy themselves with a variety of skills depending upon their level of disability. Tom excelled in cane work including mats, tapestries, baskets, small furniture and toys made for children with many of his productions being sold at Montecillo’s popular garden parties.

Since Jessie and Nola’s move to 8 Haywood Street, Tom’s visits began to become less frequent. On occasions Tom would totter across to Haywood Street after tea to visit Jessie and Nola but only a brief visit before returning to the sanctuary of Montecillo. Once in a while he would stay the weekend, usually wandering aimlessly about the house with little interest in going anywhere or doing anything in particular, circumstances which sadly left Jessie and Nola feeling quite isolated and alone for many years. The longer Tom stayed at Montecillo, the more dependant he became on the routine and security of the home, and even more so as he aged. Year after year his headaches and seizures continued albeit less frequently with aid of medication, but without possibility of elimination. The toll of the seizures on Tom’s physical being, his will and attentiveness led him to become an old man before his time, living out a life of aimless routine he was unable to alter, such was the legacy of Gallipoli for this veteran.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rest In Peace

When Tom’s wife Jessie Kelman McCarthy passed away on 17 December 1952, life for him became a little more lonely and isolated however, his daughter Nola’s marriage and the arrival of grandchildren was a decidedly bright spot in Tom’s otherwise mundane existence. Occasionally he would venture out for a drive with his family but more often than not was quite at home with the surroundings and comfort from the exceptional care the Montecillo staff gave their star boarder.

The truncated life of a once bright and enthusiastic twenty one year old soldier who went to war, no doubt with aspirations and plans for the life ahead of him (provided he wasn’t killed!) had morphed into an endless cycle of pain, distress and medication.

The nightmare for 9/732 Trooper Thomas Frederick “Tom” McCarthy, Otago Mounted Rifles and NZ Field Artillery, finally ended on the 2nd of May, 1972, just twenty six days short of his 79th birthday. Unbeknown to Tom, his residence at Montecillo had garnered him the unenviable title for which he would forever be remembered: Montecillo’s longest resident for 40 years and 150 days! Against all odds, Tom McCarthy had survived the head wound he received in 1915 to reach old age, marry and leave a legacy in his daughter Nola, Jenny’s mother. With Tom’s tortured life at an end, he was laid to rest with Jessie at the Andersons Bay Cemetery, Dunedin. May he Rest In Peace.

Thanks to GT for making Jenny’s wish come true. As an aside, when the medals were initially handed over by the donor’s agent, the irony of this meeting was not lost on either the donor’s agent or Jenny – each happened to know the other! The agent at one time many moons ago had been a primary school pupil Jenny had tutored in English. Jenny recalled the agent even at that tender age had shown a marked interest in all things military – this reunion must have meant to be? MRNZ’s medal mounting expert Brian Ramsay has since court mounted Tom McCarthy’s medals and returned them to Jenny.

Additionally, my thanks to Kelvin P, the donor of the Silver War Badge (SWB) NZ 7380 attributed to Thomas Frederick McCarthy which had been dug up in the garden of his parents home some years ago.

Note: Tom McCarthy’s personal photograph album has been entrusted to the Toitu Otago Settler’s Museum.

Still Missing: The last remaining item representing Tom McCarthy’s military service which he wore during his years at Montecillo that Jenny would dearly like to have returned, is his Returned Soldiers Badge engraved with the number 9/732 on the front. This has not been seen for many years and may even have been buried with Tom. If however it is in the community, please consider returning it to Jenny.

Source acknowledgement: ‘Holding the High Ground’ – A History of Montecillo 1918-1928 … by Billy Barnz (2018)

The reunited medal tally is now 462.