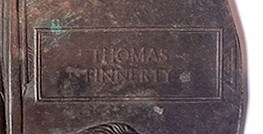

During a clean out of his mother’s house in Christchurch, Gerald came across a First World War Memorial Plaque (aka ‘death penny’) named to THOMAS FINNERTY his deceased father had acquired some 30 years before at an auction. Gerald approached a friend, Iain Davidson, well known to Facebook followers as the website owner of “Unknown Soldiers of the NZEF”. Gerald’s family was keen for the plaque to be returned to the descendant family of Thomas Finnerty and so contacted Iain for his advice – Iain in turn contacted me for assistance.

Whilst I will endevour to place any medal with a near descendant of the original named owner, with soldiers or nurses killed of who died of wounds or disease, it is not always easy particularly if they were unmarried and had no children to develop a family lineage from. It is then sometimes necessary to start tracing sibling’s families or aunts and uncles families to strike a near connection. This is even more difficult with immigrant families who either died out, did not have a family in New Zealand or, when the immediate family was small in number. Such was the case with the Finnerty family of Muckrush, Annaghdown in County Galway, Ireland.

Finnerty of Muckrash, Galway

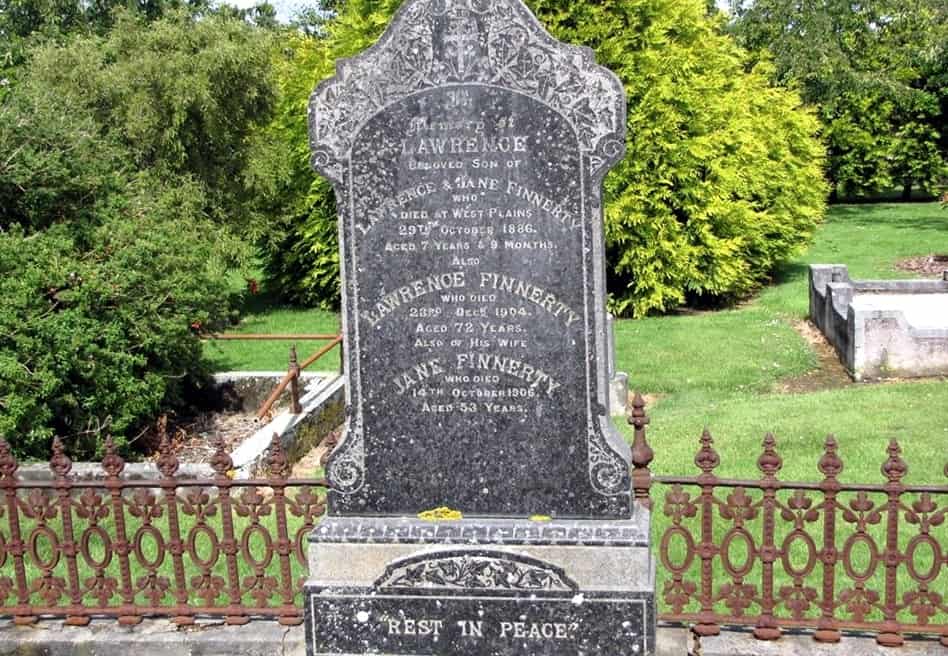

The Finnerty’s were/are a family of from Muckrush, Annaghdown in County Galway. Lawrence FINNERTY (1832-1904) was 72 when he died in Invercargill in 1904. Numerous Finnerty families emigrated from Ireland to the United States between 1845 and 1852 following the Potato Famine. Lawrence, a Labourer, emigrated to America in 1854 at age 19 aboard on the Edward Hanly. He, like so many others, was enticed by the Californian Gold Rush which started at Coloma in 1848-1855 and attracted over 300,000 people. Following this rush were the discoveries of gold in Victoria (Ballarat, Bendigo & Beechworth), in NSW (Bathurst & Gulgong) and in Western Australia (Kalgoorlie & Coolgardie). Many of these miners kept going still further afield after rushes began in 1861 at Gabriel’s Gully in Otago followed by Westland and Coromandel.

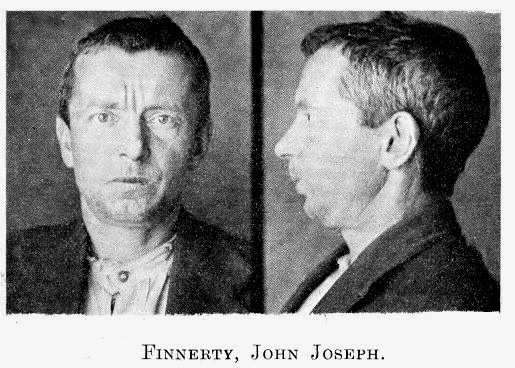

Lawrence Finnerty followed them all, arriving in New Zealand a single man and finishing up in Invercargill where he married his wife Jane Catherine STYLES (1853-1906) in August 1874. The Finnerty’s lived on a freehold property at Western Plains that Laurence had acquired prior to his marriage to Jane. The West Plains (part of the Southland Plains) are located north-west of Invercargill and north of Otatara. The Oreti River and its tributary Makarewa River, flow through the plains. In 1882 Laurence also bought an acre of land in Yarrow St, Invercargill and built a home. The Finnerty’s had a family of five: Lawrence Finnerty Jnr (1879-1886, died at the age of 7yrs 9mths), John Joseph Finnerty (1880-1954), Thomas Bernard (b:1883), James Finnerty (1886-1946) and Elizabeth Jane Finnerty (1888-1954).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

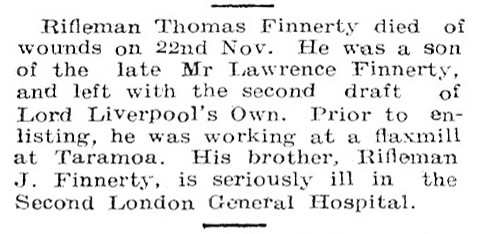

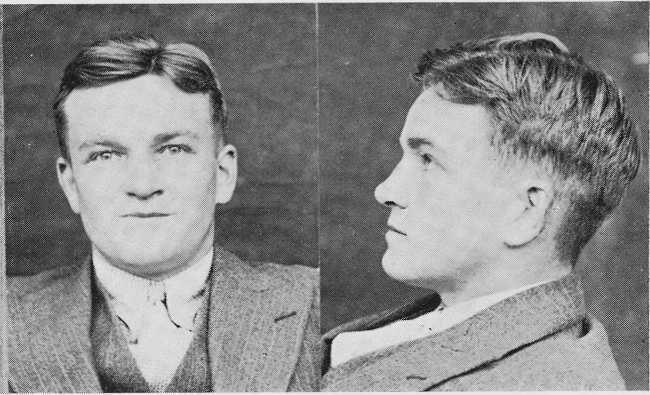

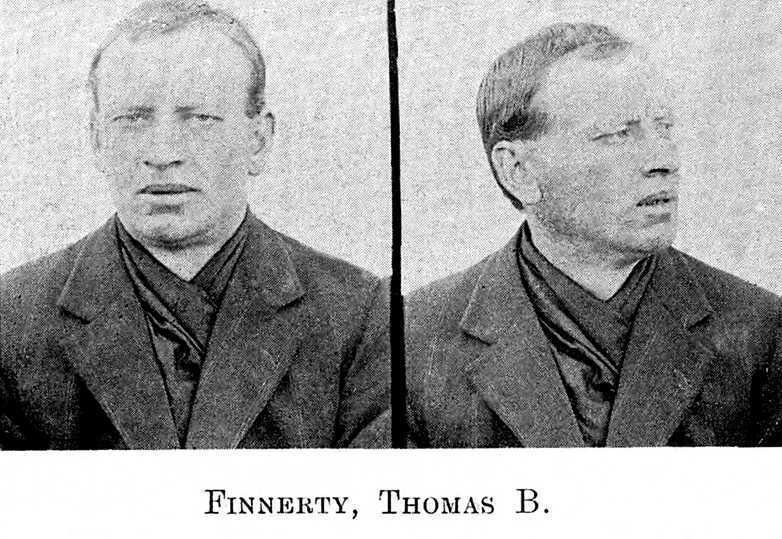

Thomas Bernard Finnerty was born at West Plains, Invercargill on 12 June 1882 and attended the Park School in the suburb of Waihopai. Prior to WW1 he had worked as a Labourer at a rabbit processing factory near Winton, and most recently in a flax mill at Taramoa, adjacent to Oreti Beach bordering Foveaux Strait.

Invercargill pre-1900 was a fairly rugged place, filled with many migrants who had arrived chasing the Otago gold once the Australian fields were at capacity. Those who didn’t find their fortune became farmers or gravitated to towns and cities, settled and began families. The established in 1885, was an important voice in the temperance campaign. Women were widely thought to be among the worst affected by alcohol, in an era when they were largely dependent on men for money to sustain the home and family. Invercargill was a ‘no-license area’.

Thomas Finnerty and his brothers John and James were of similar age, there being only three years between each. By 1890, Thomas had abandoned the Finnerty home at West Plains and boarded in the central city while making a living from whatever work he could find, generally as a Labourer. When out of work Thomas drifted. It would be fair to say the Finnerty family was a dysfunctional one and while John and James had remained living at home with their elderly parents, Thomas went his own way sometimes working, but more often drifting to other South Island towns such as Dunedin, Timaru and to the West Coast. There were not too many places he went where he didn’t finish up in trouble, invariably occasioned by liquor.

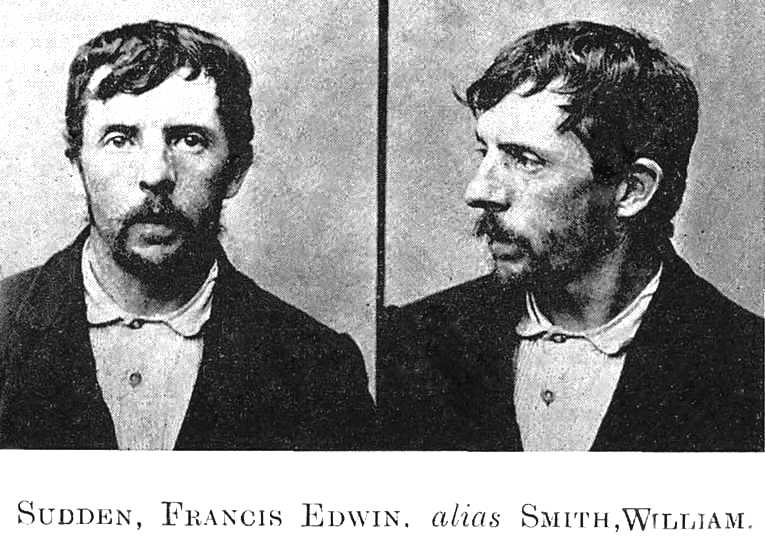

By 1905, Thomas then 22 years of age seemed content to be idling his way through life between jobs, drinking beer and making court appearances. Having returned to Invercargill for Easter in 1905, he and a number of ‘friends’ had begun drinking at an early hour on this long weekend, a decision which ultimately led them to a crime that had significant consequences for them all. On Good Friday, 21 April 1905, the alcohol had emboldened the group to carry out a series of assaults that became widely publicized in South Island newspapers. After their eventual arrest, Thomas Finnerty and three others – Albert Prentice (23), Frederick Rogers (25) and Francis Edward Sudden (24) were sent to trial for offences committed separately and together, the most serious being against one of the plaintiffs, a Mrs Annie Cashman O’Shannessey of Jackson Street, Invercargill East.

The four men were indicted on the following charges:

- Indecent Assault – ‘Assaulting indecently a married women when accompanied by her husband in the East Street, Invercargill on 21 April 1905.’

- Aggravated Criminal Assault (rape) – ‘Forced their way into a house on Jackson Street and committed rape on an old, feeble woman, frail and in delicate health, on the evening of Good Friday, with revolting and ultra-bestial circumstances. They treated the woman most outrageously, afterwards destroying her belongings and the windows.’

- Indecent Assault upon the said person, and, on the same day,

- Assault of the said person, so as to cause actual bodily harm.

Aggravated Criminal Assault (rape) near Winton – Sudden only

The Invercargill Stipendiary Magistrate committed the young men for trial on 27 April. Bail was refused as the accused men had no stake in the country.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Annie Cashman O’Shannessey

The victim, Annie Cashman O’Shannessey of Jackson St, Invercargill East was a married woman and although estranged from her husband was discovered to have been a bigamist! A review of O’Shannessey’s background paints a picture of a unrefined female who was also undoubtedly no angel, a single woman who moved in the circles of some of the less desirable citizens in Invercargill, in the company of men and partial to liquor.

Born Anne Cashman VAUGHAN she was baptised 22 May 1854 at Macroom in Cork, Ireland, the daughter of Daniel and Cate Vaughan, nee Cashman. Anne Vaughan, known to all as “Annie”, was 20 years of age when she emigrated from Queenstown, Cork to New Zealand on 8 February 1874, together with 164 other single women (servants, cooks, domestics etc) to New Zealand aboard the East Indiaman Asia. The Asia arrived at Port Chalmers on 27 April 1874 and for the next two years Annie Vaughan, whose occupation was given as General Servant, was employed in domestic positions around Dunedin City.

A little over two years after her arrival, Annie Vaughan married 25 year old Englishman Benjamin WELTON (1850-1886) at the Knox Presbyterian Church in Dunedin on 14 June 1876. Unbeknown to Annie, Welton who had recently arrived from Australia, had had several prior run-ins with the law in New South Wales for which he had also done some jail time under the name of Benjamin WILTON (probably a spelling error). Welton and Vaughan appear to have been of a similar ilk in that liquor played a major part in their lives however for some unknown reason, after just eight weeks of marriage, Welton abandoned Annie and went back to Australia.

In August 1879, it was reported in the Australian newspapers that Welton (28) had appeared in the Hay Court on a charge of Abduction (Hay is an outback town about due west and midway between Sydney and the South Australia border). Welton had allegedly coerced fourteen year old Mary Bridget Booth [in guardianship], an unmarried girl under the age of 16 years, into running away from her legal guardians with him with the promise of marriage. This, while Welton was still married and Mary completely unaware of his married status. In his defence Welton admitted that his “.. wife was in New Zealand, hadn’t seen her for three years and didn’t know if she was dead or alive”. The Magistrate found Welton guilty of the Abduction offence and sentenced to 12 months in Deniliquin Jail, however gave him the benefit of the doubt re his alleged “abandoned” marriage status, saying that he would consider suspending Welton’s jail sentence IF he could marry the girl lawfully. Welton couldn’t as no legal separation and divorce had occurred … and so the sentence stood. Welton went to jail!

As an aside, in October 1886 evidence given at a Coroner’s Inquest hearing that was published in the Bathurst Free Press & Mining Journal dated 19 October, recounted the circumstances of Benjamin Welton’s death. In 1885 Welton had married Mary Anne HADDON at Young, NSW (unknown if he had divorced Annie by then or not?). Their marriage was barely eleven months old when Welton, a Labourer living at Marengo, met an untimely end. It was reported that Welton had been hospitalized at Grenfell with severe injuries to his skull. He had sustained a brain injury, a fractured jaw, fractured right collar bone and severe bruising to his back. It transpired from the witnesses evidence that Welton had joined with a group of prospectors in Coolgardie and had been riding north with the group and a number of pack horses. Welton had been drinking heavily in Coolgardie before the group left and was alleged to have been intoxicated by the time he caught up with the men. Witnesses from the group further testified that when one of the pack horses bolted, Welton (allegedly) gave chase and was subsequently thrown from his horse in the process.

Welton was eventually picked up by his brother-in-law and taken by cart to the Grenfell Hospital. His brother-in-law told the court that on the few occasions Welton had been conscious he had said that he ‘did not fall off his horse – that he was dragged off it … and mobbed.’ There may have been some truth to this as Mary Booth’s ‘abduction’ had raised the ire of her guardian’s sons and relatives who were prepared to exact revenge for Mary’s abduction however, Welton’s utterances were put down to the ramblings of a man with serious head injuries and therefore ignored by the court. Welton died of his injuries a few days later on 6 October, his death ruled as being occasioned by being “thrown from his horse”. Welton’s wife Mary Anne at the time been staying with her mother as she was about to give birth to their first child. Benjamin Welton died on the same day Mary Anne gave birth to a daughter!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The back story ….

Back in Invercargill, Benjamin Welton’s estranged wife Annie Cashman WELTON had also re-married, in 1885 to Michael Francis O’Shannessey (various spelt O’Shannesy, O’ShauneSsy, O’Shannassy, O’Shannassey, O’Shannessey), a Miner from Waikaia some 50kms north of Gore. Francis was born in Victoria, Australia around 1850 and emigrated as a child to Southland where his parents settled at Waikaka Valley. Francis had been a formation member of the Waikaia Volunteer Corps in 1867, and as a young man seemed to have a talent for finding gold. Prospecting became his way of life which in time proved to be very successful and around which he developed his business interests. Francis developed several payable gold claims in the Riverton area and on Orepuke island in the Foveaux Strait. In June 1887, Francis hit the jackpot after prospecting in the Wilson’s River Gorge produced a payable gold vein on his claim which he named the Gold Site Reef, interestingly a claim he was alleged to have ‘jumped’ that had belonged to two Chinese men. Court proceedings proved the Chinese while having pegged out the site, had failed to re-new their claim and so the court ruled in Francis’s favour as the legitimate owner. The reef ran for several hundred meters downhill through the Waikaka Bush however Francis an his co-investors experienced substantial delays while access was created in this remote rainforest and equipment moved to the site.

Note: The mine site is within a gorge on the Wilson River, 4 kilometers from Preservation Inlet, and can still be accessed by walking along the old tramway maintained by DOC. Due to the site’s remote location, little subsequently happened for a time. The prospectors sold a fourth share in the claim to raise money for equipment, and the Golden Site Mining Company was formed. Meanwhile the government began a slow process in constructing a tramway through the thick rainforest to the location. Inclement weather, a lack of supplies, and a disgruntled poorly paid workforce all inhibited the development of the mine.

The mine opened with a ten head battery in 1894, and over the subsequent thirteen month period it produced 640 tonnes of ore for 666 ounces of gold. By the end of 1895, 1,155 tonnes of ore had been extracted for 875 ounces of gold. Gold values in the reef then decreased. The company was reconstructed in 1897 as the New Golden Site Extended Company, and by 1899 the main shaft was down to 210 feet with two levels. Poor returns continued and the mine closed in 1901, and the battery was sold. The mine was taken over by Webster (surname) of Invercargill in 1907, but it never re-opened.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

But all was not well in Francis and Annie’s marital circumstances. In 1889 Francis received some disturbing information that his wife of four years had in fact been a married woman at the time he and Annie were married in 1885 – and she still was! Francis was appalled and engaged a Dunedin solicitor to make enquiries on his behalf with the Dunedin Police re Benjamin Welton, the alleged husband of Annie. Concurrent with the investigation, Annie O’Shannessey’s social misconduct escalated with alcohol usually being the aggravating factor and which has seen her jailed on prior occasions for a week or a month at a time.** She had proven to be a volatile wife and prone to violence especially with drink in her.

In one reported instance during 1897, Annie had been drinking beer at home with a middle aged Irish woman, Ellen Swanson, and one other. When prompted by Swanson to buy more beer (from a licensed brewer in a non-dry area) as it had run out, Annie’s reluctance to do so resulted in hair pulling, shouting and abuse which had a sequel later in the day. O’Shannessey had gone to Swanson’s Mary Street house that same afternoon and an argument developed. In the course of this, Ellen Swanson accused Annie of behaving in a familiar manner towards her husband Wesley Swanson (after he had grabbed her and sat her on his knee).

The shrieking began and escalated into a full scale fight between the two women. Crockery and other articles were hurled resulting in serious injuries and blood loss before the two women were separated by Wesley (see ‘Kilkenny Cats’). Being the initiator of the fight, Ellen Swanson was duly fronted before the Magistrate on charges of assault which netted her a three months in jail.

Note: ** Annie O’Shannessey when not under a Prohibition Order, regularly ordered two, 1 Gallon kegs of beer to consume at home (a one gallon keg of beer at this time cost the equivalent of 23 cents!).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Clearly Annie O’Shannessey’s drinking habits and her temper made life with her untenable for Francis while her social conduct was an on-going source of personal embarrassment. Francis O’Shannessey opted to move out of the house and stayed at Riverton for a period and his mining interests in that area, initially to defend another charge of alleged ‘claim jumping’, this time by another who sought to take his sea-beach claims, one at Orepuki and the other on Crayfish Island (these cases he successfully defended). Further court action resulted from water rights access for his Wilson’s River claim. Somewhat disenchanted with the business arrangements and seeming endless holdups in developing Golden Site mine, Francis made plans to quit the region. In the meantime, aware of his new found (potential) wealth, Annie O’Shannessey lodged a claim with the court in 1889 for Francis to provide her with financial support, claiming that without it she would otherwise be destitute – Francis was instructed by court order of 30 October 1903 to make provision which he did.

In the interim, Benjamin Welton was eventually traced in Australia and found to be well known by the courts. In due course Francis received confirmation from his solicitor that Annie had indeed been married to Benjamin Welton at the she and Francis were married in 1885 (and she still was!). This, together with her drinking habits and alleged immoral behaviour since Francis had left, must have been the last straw for Francis. He applied to the court to have the order for financial support cancelled on the grounds he objected to paying for his wife’s support as “she spends all the money on drink and is living an improper life”. He was unsuccessful.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Annie O’Shaunnesy’s penchant for liquor and her fiery disposition while under its influence, was well known, to the extent that at the time of her assault, she was the subject of a Prohibition Order ** that banned her from procuring or partaking of alcohol for the duration of the order. Annie must have been aware that her path to self-destruction was assured if she continued down this path. The departure of Francis may well have resulted in an epiphanous moment for Annie as her Prohibition Order was self-imposed! Despite the Order, Annie soon reverted to type, circumventing her access to liquor by having others procure it for her and delivered to the house. One of her suppliers (a neighbour, Benjamin Harcourt) was caught in the act and arrested for his trouble by a wily police constable who knew Annie’s caper only too well as he had been keeping a close eye on the comings and goings to her Jackson Street house. Harcourt was fined a hefty sum in court and had his old age pension cancelled!

In September of the same year, Annie O’Shannessey was again up before the Magistrate, charged and found guilty of riotous conduct while drunk at Avenal (a suburb of Invercargill). Extenuating circumstances (probably the departure of Francis?) said a sympathetic judge, reduced her fine to just £1.0s.0d (one pound = $2.00). This was to be the pattern of Annie Cashman O’Shannessey’s life until her death.

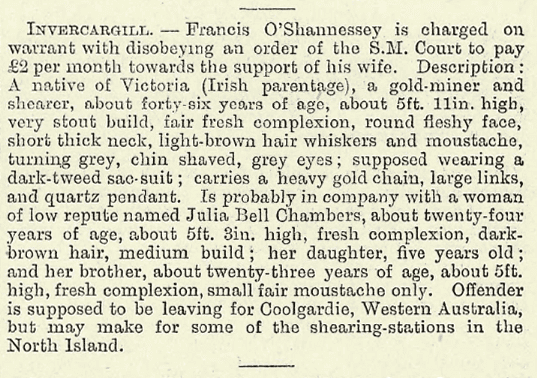

Note: **Aside from his sham marriage Francis O’Shannessey had had enough of endless litigation over water access rights to his gold claims, and defending himself against allegations of claim jumping related to the Golden Reef Site on Wilson’s River. He sold his mining interests in Otago/Southland and rapidly left for Australia, allegedly with a woman of ill-repute? However, he had in effect deserted his wife by ceasing to pay her maintenance. The result was an arrest warrant issued in his name that appeared in the NZ Police Gazette in Oct 1894.

After spending some months in Melbourne to assess the mining situation and establish himself, Francis made for the most productive gold producing area in Western Australia, arriving on 13 Nov 1894. When writing to a friend in Waikaka in August 1895, Francis said that since he arrived and began prospecting around Coolgardie, he had” … struck gold in a big way .… this is the greatest place in the world for reefs, hundreds of miles of them in every place you go“. While Francis lamented the heat, the dry conditions and the loneliness, “luck” he said had been a large part of his success however, he would not advise anyone to go there as many gold seekers had been in the Coolgardie for years and never found an ounce. “There are hundreds of men starving and hundreds of men making a fortune” he said in his letter.

Fortunately for Francis he was one of the latter, making his first find within just three weeks of arriving at Coolgardie. He had since made another substantial strike which he sold a few months later to a large Queensland mining company at Mount Morgan, for £40,000 – the equivalent today being NZ $14,350,366.00! Francis was a rich man and so he continued to invest in mines and mining companies. In 1900 Francis was the Mine Manager of Burbank’s United Gift Mine in Queensland in which he had a quarter share.

His tenure as the manager came to abrupt end when he resigned after a particularly nasty incident at the mine. An attempted murder at the mine was committed by a man known to be inoffensive and a well behaved workman. The man, who had been drinking in Coolgardie for three days before the incident, was alleged to have suffered sunstroke as the result of falling asleep in the sun on the side of the road. When awoken in an seriously affected condition, he was alleged to have attempted to murder a fellow miner he trapped inside the mine shaft. This case was widely reported as it resulted in the accused being sentenced to death by hanging. (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/88403617?searchTerm=Francis%20O%27Shannessy).

While Francis knew as well as anyone that the ‘mining industry giveth, and it taketh away’ just as quickly, this incident caused him to change course in the way he lived his life. Francis sold his share in the mine and returned to prospecting in Western Australia. By 1903, much of his accumulated wealth had been given away in acts of benevolence whilst he retained some stock in a Victorian bank. In returning to prospecting he withdrew from city and town life and those who lived therein, choosing to live a ‘hatters’ life. A “hatter” was a person who preferred living having become alone in a remote area of the Australian bush, as a herder or prospector, often becoming quite eccentric. Hatters lived simply, ate simply, worked odd jobs, prospected and panned for gold. Whatever they did or found was just enough to get by. Some moved about from place to place while others preferred to stay in one spot (often in remote areas and far away from people) constructing their homes from whatever material they could find or lived in makeshift shelters such as hollow logs.

Philosophical over his losses, Francis O’Shannessey remained a benevolent man, one of sober habits who was well liked despite living as a pauper. Francis never re-married and received a meagre income from some mine stocks he still had in Victoria which he used mainly for the benefit of local Aboriginies. In return Francis was provided with gifts of food while prospecting and made a little extra from rounding up stray horses and stock in the bush.

In April 1904, an article was published in a Coolgardie newspaper, The Sun, which outlined the type of man Francis O’Shannessey was despite being the subject of persecution by a petty local Police constable. The policeman thought Francis was up to no good after spotting three ‘gins’ (female Aborigines) in his camp, and so arrested him alleging they were there for immoral purposes. Francis denied this and while the charge remained unproven, the vindictive copper had Francis charged with being an alternate offence for being an “idle and disorderly person without lawful means of support.” The court proceedings proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that Francis’s intentions had always been honourable and that his conduct was beyond reproach. Being a ‘hatter’ Francis had no need to demonstrate visible support. He had simply been assisting the local doctor by taking medicines out to his encampment for distribution to the doctor’s Aboriginal patients. This was a preferable arrangement as it precluded the need for his Aboriginal patients having to come to town for their medicines where they would be invariably ill-treated and abused by the locals….. read Francis’s full story here: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/211597167?searchTerm=Francis%20O%27Shannessy

Francis O’Shannessey lived this subsistence lifestyle for the remainder of his days. His persecution by the Police because of his friendliness towards the Aborigines whom he had no preconceived biases towards, persisted. The police were convinced Francis was conducting some sort of clandestine liaisons with Aboriginal women since they were observed to be frequently coming and going from his camp, and had even been seen inside his accommodation.

One of the last articles about Francis reported in the newspaper occurred in 1913 as he was moving his camp from Gnarlbine to Widgiemooltha, 631 kilometers east of Perth. Again the Police were onto him, searched his encampment on a trumped up excuse of searching for stolen tools. During the search they discovered a half-caste Aboriginal girl named Alice hiding under a cover in Francis’s spring cart wagon. Alice had previously been before the court as a neglected child. Francis was charged with consorting with Aboriginals, “co-habiting and travelling with an Aboriginal girl of 14 years and three months.” Had the case been properly investigated, they police would have found that Francis in fact only intended giving Alice a lift on his way to a new camp site as she had been abandoned by her parents. Francis was guilty of nothing ….. the story here in the ‘Coolgardie Miner’: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/85682527?searchTerm=michael%20Francis%20O%27Shannessy

On the 26th of November, 1916 the newspaper carried the news of Michael Francis O’Shannessey’s death at Coolgardie, described as “an old and familiar prospector”, aged 66. The value of his Estate was the princely sum of: £1.11s.10d ($3.20c).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Invercargill Supreme Court – the evidence

To the primary charge against Thomas Finnerty, Albert Prentice and Frederick Rodgers, Mrs O’Shannessey gave evidence stating she had been sitting in her kitchen at the back of her house in Jackson Street between 10:30 and 11:00pm on Good Friday, 21 April 1905, when she responded to a noise at the back door. She opened the door to five men who, led by Prentice, rushed inside. Prentice made a demand of her which she refused saying she was unwell in the hope she would not be molested. Prentice then knocked her down to attain his objective. The details of the participant’s indecency was unprintable. One of the men had also proceeded to smash the windows, crockery, pictures and everything that was breakable in the house with an iron bar.

The following morning Annie O’Shannessey had complained to her neighbour (Benjamin Harcourt) at the police camp that she had “nearly been murdered by five blackguards the previous night” and then had visited Dr. Mulholland for her injuries. She presented with both eyes blackened, her face blue and bruising to her back. While visiting a woman later in the day, as the two women stood outside her friend’s house, five men had passed by including Finnerty and Prentice. Prentice had called out in a show-off manner making reference to the events of the previous night.

Mrs O’Shannessey did not lay a complaint with Police until the following Sunday which very nearly saw the men avoiding a charge. Ironically, when she arrived at the Invercargill Police Station on the Sunday to lay a charge, Finnerty and Prentice were both there on another matter. It seems they were trying to have Thomas Finnerty’s brother James and five others bailed after they were locked up for various acts of misconduct on the previous Saturday night. Annie O’Shannessey immediately identified Albert Prentice and Thomas Finnerty as two of her attackers whereupon they were immediately charged and placed in custody. Neither man denied the charge.

Outrage – the verdict and sentencing

The alleged assault on Annie O’Shannessey generated much public outrage that was expressed through a number of letters to the Editor of the local press, to the extent it caste serious doubt as to whether or not a jury of unbiased citizens could be found in Invercargill? As one letter (right) to the press stated, “The only explanation of the unspeakable conduct of these criminals is that they were demented by the liquor they had before setting out on their deeds of infamy.” An application for the trial to be heard in the Dunedin Supreme Court was however rejected and the trial went ahead in Invercargill. Appearing for Thomas Finnerty was no lesser legal mind than the renowned criminal law advocate, Dunedin lawyer Alfred Charles Hanlon K.C. (1866-1944). Unfortunately this did not help the outcome for Finnerty or Prentice. Mr Hanlon had queried the nature of various visitors to Mrs O’Shannessey’s house as well as her taste for liquor but this held no sway over the Magistrate?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On 31 May 1905, the Common Jury of the Invercargill Supreme Court found the prisoners Finnerty, Prentice, Rodgers and Sudden Guilty on several counts. Before passing sentence on Finnerty and Prentice for the primary charges, his Honour Justice Williams remarked:

“You, Prisoners, have been convicted of the gravest offences known to the law, and the maximum punishment is imprisonment for life and three floggings.” I don’t intend to inflict the maximum punishment, and as to the floggings, although it is very repugnant for me to inflict it, but if ever there was a case to inflict it, this is the one. If it isn’t inflicted in this case, it might as well be wiped out of the Statute altogether. The circumstances under which the crime was committed are of the most disgusting character and no words can express the disgust of every decent member of the community in respect to your conduct.”

“You are each sentenced to 12 years Imprisonment with Hard Labour, and each to receive one flogging (with the Cat o’ Nine Tails) of 25 strokes.”

- On the primary charge of “criminal assault” (rape), of Mrs O’Shannessey, Thomas Finnerty and Albert Prentice were found Guilty. Frederick Rodgers was found Not Guilty of the outrage.

- Frederick Rodgers was already serving a six month sentence for the attempted ‘indecent assault’ in the East Street at the time of the court case. While he was found Not Guilty of ‘criminal assault’ of participating in the outrage upon Mrs O’Shannessey, Rodgers was found Guilty of assaulting her and destroying her property with an iron bar. Rodgers also had prior form – six previous convictions, two being assaults on women – the first being the assault of a hotel landlady who had ordered him off the premises for misbehavior. Accordingly, Rodgers was sentenced to an additional six months for his assault of Mrs O’Shannessey (served concurrently) plus a further three years Imprisonment with Hard Labour for smashing up her house. The judge also ordered that the £5.00 (pounds) and 3d (three pence) found on Rodger’s when he was arrested, was to be paid to Mrs O’Shannessey for the damage.

- Edward Sudden was found Guilty of “criminal assault” (rape) of a woman (un-named) near Winton and imprisoned for 10 years with Hard Labour.

Note: Thomas’s father Lawrence Finnerty died in 1904 aged 72, and his mother Jane Catherine Finnerty, six months after Thomas was jailed in 1905.

Jail time with Hard Labour !

Leaving the courtroom, the prisoners who had previously appeared unconcerned during the proceedings, were visibly stunned at their sentence. The prisoners attempted a brave face by thanking His Honour. Thomas Finnerty as he exited the court addressed a “good-bye boys” to the crowd. Both were booed and hissed at as they left the courtroom under police guard to begin their sentence in the Invercargill Jail.

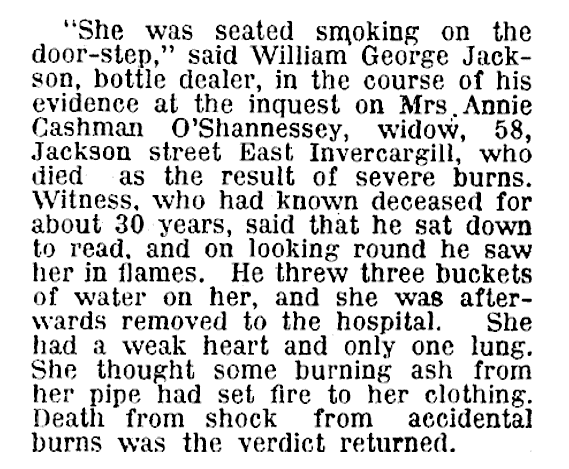

Annie Cashman O’Shannessey’s life changed little thereafter. Her demise came some 12 years later at the age of 58 , not from natural causes but in circumstances of her own making. Annie O’Shannessey died at her Jackson Street house on 18 January 1918. An ‘intestate widow’ with no family, her death was reported in the SOUTHERN CROSS following a Coroner’s Inquest:

DEATH OF ANNIE CASHMAN O’SHANNESSEY

Annie Cashman O’Shannessey is buried in an unmarked grave at the Eastern Cemetery, Invercargill.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To the Front

Thomas Finnerty took his thrashing and did his time with Hard Labour at the old Invercargill Jail. Due for release in June 1917, Thomas’s only opportunity for even a small amount of remission from the remaining months he had behind bars was to enlist for war service. Having completed 10 years ‘at His Majesty’s pleasure’, the bulk of his sentence was done and so the possibility of an early release and travel overseas had considerable appeal, after all, he had nothing to lose.

Thomas underwent a pre-enlistment medical check on 24 June 1915 with an Invercargill doctor who described him as: “five feet, eight and a half inches tall (178cms) with brown hair, blue eyes, a fresh complexion and weighing 151lbs (68.5kgs).” He was 32 years and 11 months of age. As he had disassociated himself with his parents, Thomas spent his pre-embarkation leave at 130 Spey Street (now a car park) in Waihopai, Invercargill, the home of his younger brother James and his wife Jean Elizabeth Boyd (nee, Allan) who Thomas had also nominated as his Next of Kin, to be advised in the event of his injury or death.**

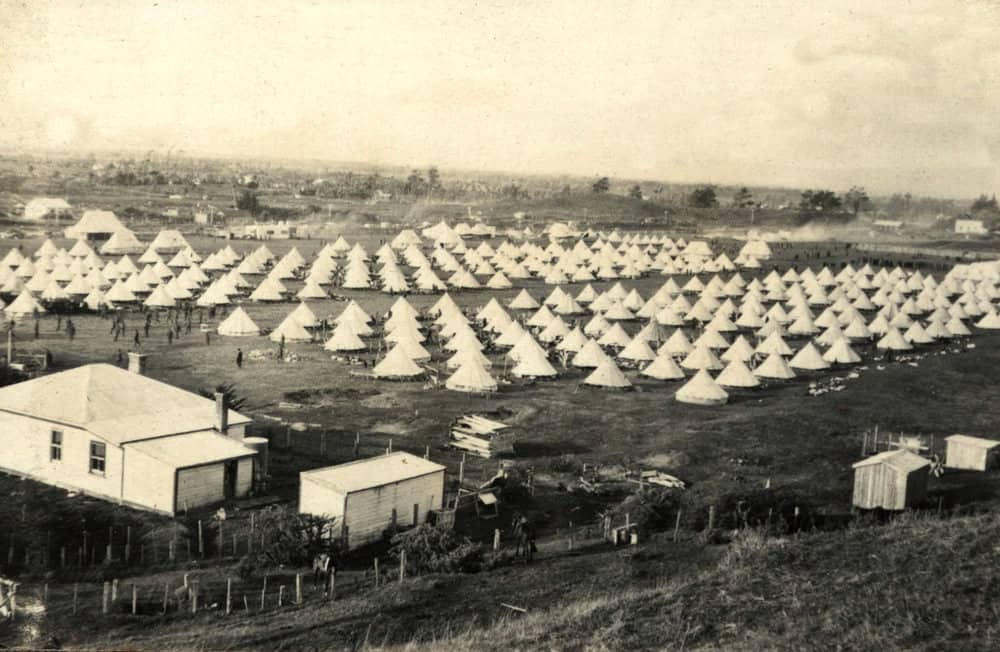

26/555 Rifleman Thomas Bernard Finnerty together with the Invercargill and Milton soldiers caught the express train to Dunedin for a farewell parade in Anzac Square. They then proceeded to Trentham Military Camp on 13 October 1915 and were attested to serve for the duration of the war. Following basic military skills and fitness training, Rflm. Finnerty and his fellows were assigned to the 4th Reinforcements of the 4th Battalion, 3rd New Zealand Rifle Brigade (or 4/3NZRB, or 4/3 Rifles).

Preparatory training of officers and non-commissioned officers commenced at Trentham on 7 September 1915, and the men marched in on the 11th and 12th of the following month. On the 15th a move was made to Maymorn, some six miles to the north of Trentham, where a tented camp was occupied and general training commenced at once.

In the matter of dress, the 3rd and 4th Battalions were in some respects more fortunate than their predecessors, for by this time some slight degree of finality had been reached. The blaze of the 3rd was a black cloth triangle of 1 & 1/2 inch side, standing on its base, while that of the 4th was a similar patch placed with its base uppermost. These were worn on the hats and caps as in the other two battalions. The puggarees that were issued however were plain khaki without the central strip of scarlet, a defect that was remedied in due time after the units joined up with the Brigade. Unfortunately the men could not be issued with khaki uniforms for some six weeks after their enlistment, and as a consequence, could not be given leave to town for that period.

Owing to continuing bad weather at Maymorn, finally the camp became untenable and at the beginning of December the battalions moved to the site of the old Rifle Brigade camp at Rangiotu where, as in those former days, much better conditions prevailed and where both the general health and the work of the units rapidly improved.

Final leave commenced on 19 December for fourteen days. Further training followed with short period of special continuous training in attack and defence, outpost work and bivouacing was carried out on the sand hills around Himitangi. This was followed by the musketry course, the 3rd Battalion at Palmerston North and by the 4th at Wanganui.

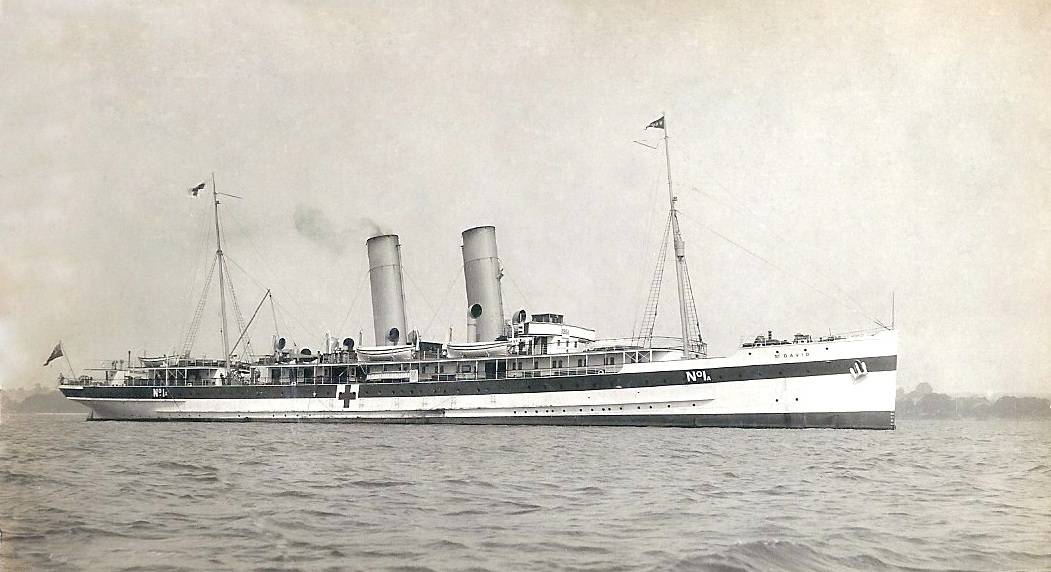

Note: ** Thomas’s younger brother James Finnerty was the only other member of the family to go to war. 23368 Rifleman James Finnerty – 2nd Battalion, 3rd NZ Rifle Brigade – 13th Reinforcements. James (29) was farming at Thornbury in Southland, married with three children, when he attested for war service at Trentham on 13 January 1916. A volunteer (conscription did not start until October), James embarked onto HMNZT 55 Tofua on 29 May 1916, just eight weeks after the birth of his third child Dorrien Boyd Finnerty. He arrived at Devonport, England on 27 Jul 1916 and after a brief period of training at Sling Camp, James was posted to ‘C’ Company of the 2nd Battalion which went to France on 12 August. He joined his Battalion in the field on 28 August and four weeks later, James was wounded in the head (scalp) on 22 September. Evacuated to 11 (British) General Hospital at Camiers, he was then transferred to the 2nd London General Hospital in Chelsea, London for the next three months. Transferred to No 1 NZ GH at Brockenhurst on 29 Dec 1916 for a Medical Board assessment, James was declared ‘no longer fit for war service due to wounds received in action’. He returned to NZ on HMNZT Maunganui and was discharged to the Christchurch Soldiers’ Settlement in Avonhead Road, Upper Riccarton on 3 July 1917 where he undertook light farm work.

His head wound plagued him mercilessly and by 1928, he and Jean had relocated to 33 Peer Street in Riccarton, living off James’s Disabled Soldiers pension. James and Jean Finnerty’s oldest child, daughter Mollie (Mary Elizabeth Finnerty) followed in the footsteps of her Aunt (and Thomas Finnerty’s elder sister), Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jane Finnerty. Lizzie had joined the Catholic order as a missionary-teacher nun, known as Sister Felicitas, who emigrated to South Africa shortly after taking her vows. Sister Felicitas remained in South Africa for the rest of her life and died at Port Elizabeth on 19 Mar 1954 at the age of 65.

Mollie Finnerty took her vows in Christchurch, joining the a Catholic nursing order, Little Company of Mary, established by the Venerable Mary Potter in 1913. Known as Sister Mary Virginia LCM, she emigrated to Buenos Aries, Argentina in 1954 as a missionary-nurse for the order. Sister Mary Virginia returned to Wellington by 1972 to nurse in the order’s own Calvary Hospital (later re-named Mary Potter Hospice) where she remained until her death in 2007, aged 91. Ironically, but perhaps predictably, Mollie’s two brothers James Styles and James Laurence Finnerty continued a long ‘tradition’ of Finnerty males appearing in the NZ Police Gazette from time to time .

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Training in Egypt

RFLM Finnerty and the 4th Battalion left for Auckland by train on 3 Feb, and after a march through the city in pouring rain, embarked on HMNZT 43 Mokia the following day. The Mokia sailed from Auckland at 1 a.m. on the morning of 5 February. The 3rd Battalion had left their camp on the 4th, marched through Wellington, embarked on to HMNZT 42 Ulimaroa and sailed at midnight on the same date. Unlike the 1st and 2nd Battalions, these two units embarked without equipment or rifles.

The transports called in at Albany on 15 February, departed on the 17th, and went via Colombo to Egypt. The troops disembarked at Suez, moved by rail to Ismailia and marched to the Brigade’s camp across the Suez Canal at Ferry Post, the 3rd Battalion arriving on March 13 and the 4th Battalion two days later.

On 20 March, the Brigade moved from Ferry Post to Moascar Camp where the battalions remained until departing for France early the following month. During their stay at Moascar, training continued with unabated energy. Company, battalion and brigade parades, route marches and staff rides, night operations and trench-digging, specialist training and transport work, each had its place until at last all ranks were fit and ready for any emergency.

Western Front

After a period of reorganization following the withdrawal of the NZ troops from Gallipoli, the full Brigade left Alexandria on 7 April for Marseilles, France. Arriving on 13 April, the battalions entrained at Marseilles for their three day journey across France to Steenbecque. The Brigade then faced a 15 mile route march to a temporary encampment they would remain for several weeks as the Brigade Reserve. In mid-May the battalions moved forward again, the 1st and 2nd Battalions marching to Doulieu while the 3rd and 4th marched to Estaires. After yet another period of training and preparation, the Brigade entered the line on 13 May to the east of Armentieres.

Battle of the Somme

On 1 July 1916, the British and French forces launched an offensive that would become known as the Battle of the Somme. The first day of the battle is regarded as one of the bloodiest days of the First World War with the loss of over 19,000 soldiers of the British Empire killed. The blooding of the New Zealand Division began in September with the Battle of Flers-Courcelette that lasted just seven 7 days from 15-22 September 1916.

At 0620 hours on the 15 Sept, the New Zealand Division fixed bayonets and advanced in four waves toward their objective, the village of Flers. Tanks were also used in this battle for the first time, by the British. Two of the four tanks attached to the New Zealand Division were knocked out by German artillery fire during the day. By the end of the day, 603 New Zealanders were either dead or dying. The Division continued fighting on the Somme for another 23 days, advanced 2 miles (3 kilometres) and captured 1,000 German prisoners of war.

For Rflm. Finnerty, I imagine his prison sentence would have been a far more preferable misery than that which faced him on the Somme. While prison may well have been a ‘battle’ that tested him in many ways, and possibly even caused him to re-evaluate his path and the future, at least there was not the threat to life or limb that there was on the Somme, and so a chance of to atone for his past misdeeds had remained a possibility. Jail however could not have prepared him for the horrors of a battle field in France. The Somme represented a battle for survival, a great leveler that would cause every man at some point to know their own mortality, to know that life was tenuous and hung by a thread on a daily basis – here today, gone tomorrow!

Whatever we may think of Thomas Finnerty’s crimes, it must be acknowledged he had all but repaid his debt to society – 10 years of Hard Labour in a Victorian era prison run by unsympathetic and ruthless members of the Armed Constabulary convinced many a hardened criminal to turn their lives around. Besides, Thomas was much older now (was he wiser?) and had had plenty of time to contemplate his future. Apart from only one indiscretion during his military service for “irregular conduct” in June 1916 for which he forfeited four days pay, on the battlefield Finnerty had proven himself the equal of most other soldiers – the good and the bad, the criminal or saintly – all required trust in each others ability if they were to survival. Soldiers during circumstances of extreme hardship and fear such as in war, are often confronted to face their reality. Regrets and contrition for past deeds are professed in silence and promises to mend their ways made to God if only they be permitted to survive. One wonders if Thomas Finnerty had been moved to make such a declaration, should he survive?

The old saying of ‘what goes around comes around’ might well have resonated in Thomas Finnerty’s mind during some quite moment, alone in the freezing rain and the snow and slush of the Somme. To live or die on that field of battle was a crap shoot; the luck of the draw where the unknown could conspire to save lives, or take them away. Thomas Finnerty would soon enough find out how the dice would roll for him – would he get a second chance to redeem himself? Time alone would tell.

Flers-Courcelette

By the beginning of November 1916 the ground was in deep snow, the Somme landscape pockmarked with craters half full of water that froze to ice, and all around for as far as the eye could see, the ground had been pulverized by the continual artillery and mortar fire. The winter conditions had reduced the battlefield to a sea of often knee-deep mud. Whatever trees and growth had existed on this land was now shattered beyond recognition. While the tempo of enemy shelling receded with the onset of winter, so to had the progress of the battle. The enemy’s determination to prosecute offensive action appeared to have deserted them for the time being, content to let the guns and mortars do the work. The NZ Brigades while still subject to intermittent barrages, these occurred less frequently than in the weeks prior, thus allowing a brief respite for units to recover and regroup before the next push was ordered.

‘What goes around, comes around’ ?

Note: ** Lobar Pneumonia is a specific type of pneumonia that affects certain lobes of one or both lungs. This in contrast to the Bronchopneumonia which affects one or more of the five lobe segments (3 left, 2 right) of the lungs, i.e. affecting the lungs in patches around the bronchi or the bronchioles. In Lobar Pneumonia, the common cause is bacterial superinfection by the Streptococcus Pneumoniae. The sputum is scanty and usually of a rusty colour from altered blood. If not effectively untreated with antibiotics, Lobar Pneumonia can result in death any time after the 7th day, i.e. characterized by a hacking cough and air starvation as the air sacs (alveoli) of the lobe exude fluid and drain through lymphatics and airways.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The morning of Wednesday, 22 November 1916 was the day of reckoning for Rflm. Finnerty. The unforgiving might say ‘he got his just deserts’ or ‘got his come-uppance’ for prior misdeeds, and possibly ‘what goes around, comes around.’ For Thomas that moment was a Wednesday, at 10 minutes after the hour of 1 a.m. in the darkness before the dawn when he succumbed to his wounds. Irrespective, it cannot be denied that Thomas Finnerty having repaid his ‘debt’ to society before going to war, had now paid this debt with interest, much more than was required of even a convict! Rifleman Thomas Bernard Finnerty in atoning for his past had paid the ultimate price, he had made the supreme sacrifice in the service of his country.

‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’… John 13:15

26/555 Private Thomas Bernard Finnerty was buried on the November 25th, 1916, one of only 16 New Zealand soldiers of the First World War buried in the Kensal Green (All Souls’) Cemetery, in West Kilburn, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Somme offensive had lasted for 141 days until winter had bought the battles to a temporary close in November 1916. The five months of fighting resulted in 420,000 troops of the British Empire wounded or killed, Thomas Finnerty being one of them.

Medals: British War Medal, 1914/18 and Victory Medal + Memorial Plaque and Scroll.

Service Overseas: 260 days

Total NZEF Service: 1 year 73 days

Descendant search

To locate a descendant of Thomas Bernard Finnerty’s family was no easy task. There are/were many families of with the Finnerty surname and predictably, most had originated from Ireland, but not necessarily related. In constructing the Finnerty’s family tree, the absence of relevant Irish records of his forebears was the result of the destruction of Ireland’s national archives during the opening battle of the Irish civil war in 1922. The use of the same or similar first names for successive generations tended to be more slavishly applied to the Finnerty’s of Ireland than to English families from the same period. Early New Zealand electoral rolls prior to 1900 notoriously listed in the main only first names, or names known by, a only areas or suburbs, house numbering came much later again making a positive identification tricky. This meant I had to segway into the lives of others of the same name in order to confirm I had made the right connection. Such was the case with Francis O’Shannessey, another Irish descendant born in New Zealand who has a prolific family name (in all its versions of spelling) in both NZ and Australia throughout this period. Finnerty family trees on Ancestry were also extensive, some of which I found had been corrupted by the common error of unrelated families being erroneously conjoined.

Identifying the family members of Thomas Bernard Finnerty’s family was a little unique in so much Irish families are traditionally numerous however this Finnerty family was small in number – just five children which was reduced to four after the eldest child, Lawrence Finnerty Jnr. (1879-1886) died at the age of seven. The next three children – John Joseph (1880-1954), Thomas Bernard (b1882) and James (1886-1986) Finnerty were relatively easy to trace with the help of Papers Past since all three men had track records of ‘issues’ with the Armed Constabulary at one time or another. The misprinting of their names and initials by the press proved frustrating and required the comparison of numerous individuals of the same name or initials. The appearance of two other “Thomas Finnerty’s” (both criminals), one in Wellington and the other in Auckland, added an additional confusion factor which I was eventually able to rule out as a number of their court appearances had occurred whilst Thomas B. Finnerty was in jail.

Theresa Imelda [Finnerty] WILLIAMS (1917-1976) was Thomas Finnerty’s cousin twice removed. Paul of Prebbleton in Christchurch is Theresa’s great-grandson and it was he who sent me an email the first confirmed descendant of the Finnerty’s I was able to positively link to Thomas’s parent’s, Lawrence and Jane Finnerty.

After Thomas Finnerty died, it was not until 192o that the New Zealand Military Headquarters issued the items that commemorated his death. Both of Thomas Finnerty’s service medals, a Memorial Plaque and Memorial Scroll in his name, a King’s Letter (of condolence) and an illuminated Certificate of Services in the NZ Expeditionary Forces that would normally have been sent to the soldiers parents were sent to a Mr C. S. Longuet, a lawyer with the Invercargill law firm of Longuet & Robertson, Barristers & Solicitors who held Thomas’s Will. Although Thomas had recorded his brother James’s wife Jean as his NOK, when his death was reported they had left their Waianiwa farm and relocated to Avonhead, Christchurch as part of James’s rehabilitation. James and Thomas’s older brother John Joseph, a Machinist, was also living in Christchurch at this time.

It is not known to whom the the Executors of Thomas’s estate gave his medals and plaque etc, but it would be logical to assume that either John or James and his wife Jean Elizabeth Allan (nee BOYD) being Thomas’s designated Next of Kin, would have likely received them. James Finnerty in 1946 and his brother John in 1954. Thereafter, it is probable that one of James’s sons would have inherited the items (provided they had not been lost or sold) from his father, until such time as they left Finnerty family ownership. This is often occasioned by the death of the last owner having no descendant children (or siblings) to pass such items on to.

As the Memorial Plaque had been found in Christchurch, some combination of these factors would have accounted for the plaque being found there. After James died in 1946, his and Thomas’s elder sister, Elizabeth Jane Finnerty (Sister Felicitas) became the Executor of her brother’s Will (from Argentina!). The plaque in all likelihood would have gone to one of James Snr and Jean Finnerty’s sons, either James Laurence Finnerty (1918-1963) or probably the last living family member, Thomas Styles Finnerty (1914-1985) and who served during WW2. Both died in Christchurch.

After sifting the results of this extensive search and the few leads to living Finnerty descendants, I decided that Paul’s connection through his grandmother Theresa Imelda (Finnerty) Williams was a close enough blood connection to the Finnerty family and therefore appropriate to have guardianship of Thomas Bernard Finnerty’s Memorial Plaque. When I contacted Gerald to advise him of Paul’s contact details, both men coincidentally worked within a kilometer of each other around Hornby and so the handover was completed with ease.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks to Gerald and Iain for a challenging case. My thanks also to the Rootschat contributors: Rosjan (a descendant of Mary Anne Haddon), Sue21757, Johnf04 and Lucy2 for providing useful references to both Francis O’Shannessey & Benjamin Welton in Australia, plus Ann Vaughan’s origins. These greatly assisted in defining the members and descendants of the Finnerty family.

The reunited medal tally is 483.

Aggravated Criminal Assault (rape) near Winton – Sudden only

Aggravated Criminal Assault (rape) near Winton – Sudden only