2/R – B/28 ~ SYLVIA DAISY BROWN, RN ~ QAIMNSR

Uncharacteristically I am starting this story with the ending, the reason for which will become apparent as you read on.

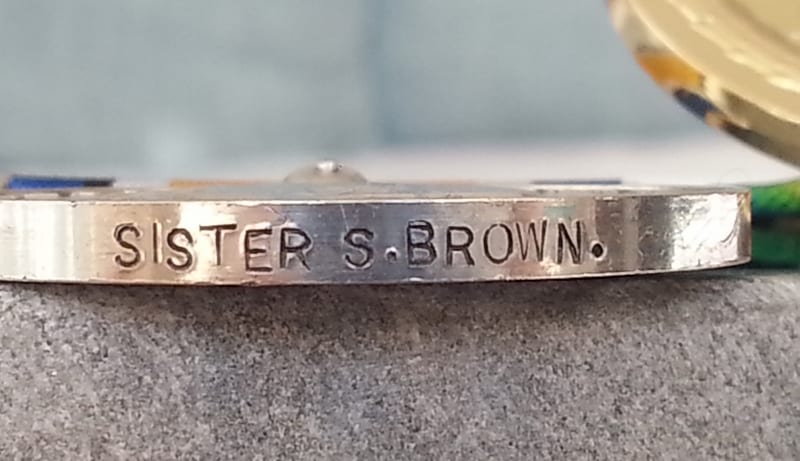

The impetus for this medal research initially came from the Nelson Police. Constable Ben Wallbank in the course of apprehending an offender had found a First World War medal in the offender’s backpack. The British War Medal, 1914-18 was named to B.28 SISTER S. BROWN. Constable Ben contacted MRNZ for help to find any of Sister Brown’s descendant family to return the medal to. As always, we are happy to oblige any request to return medals however in this case, little did I know what I was in for.

The discovery of Sister Sylvia Brown’s war medal started a lengthy journey of research to find a descendant to whom her medal could be returned. In short there were none. Because she had made Nelson her permanent home for more than 27 years, it seemed the most appropriate place her medal and history would be both appreciated and accessible, was at Nelson Hospital.

At a ceremony celebrating International Nurses Day 2019, the Director of Nursing and Midwifery at Nelson Hospital, Pamela Kiesanowski and the hospital’s Charge Nurse managers gathered to hear a summary of the research of Matron Sylvia Brown’s previously unknown background. Pamela said she was honoured to accept Matron Brown’s war medals, a first in the hospital’s historical collection. Included were a sterling silver QAIMNSR Cape Badge, the NZ Registered Nurse’s badge and a photograph of Matron Brown whilst at Nelson Hospital. The memorabilia will be displayed in an appropriate position for all to enjoy.

Note: Sylvia Brown’s British War Medal, 1914-1918 is accompanied by a replacement Victory Medal to complete her entitlement for display purposes. MRNZ remains ever hopeful the original Victory Medal will re-surface so that it can be reunited with her British War Medal. There is every possibility the missing medal is also still in Nelson. If you can provide any information that will help us to locate the missing medal, please contact Ian at MRNZ.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My personal thanks are due to a number of people who have contributed in a variety of ways to complete this story.

The first is to Constable Ben Wallbank of the Nelson Police for contacting after finding Sylvia Brown’s medal for without it there would be no story or research into the unknown background of Matron Brown; to Nelson historian Cheryl Carnahan and researcher Lorraine M. for supplying background material that assisted my research, and to Mr John Liell, Archivist at Nelson Hospital, for use of the only three photographs of Matron Brown, all of which are contained in this post.

Special thanks to Director of Nursing & Midwifery at Nelson Hospital, Pamela Kiesanowski for generously providing for Matron Brown’s memorabilia to be framed.

I am also indebted to the two UK based ladies – Andrea Ruddick who is a part-time researcher for MRNZ, and to Sylvia Ramsay (nee Brown – unrelated), an amateur genealogist who responded to a question I posted on Ancestry.com. Both ladies were most helpful in establishing the way ahead for me by providing ancestral leads to Sylvia Brown’s extended family.

Finally, my thanks to three other contributors to this project; first is to noted Nelson ‘cemeterian’ Brian McIntyre who so ably restored Matron Brown’s bronze grave plaque in time for the wreath laying, second to my colleague Brian Ramsay for expertly mounting the medals, and third, to a former work colleague, photographer and picture framer extraordinaire, Mr Peter Wise of Wise’s Picture Framing, 78 Buxton Square, Nelson for the superb job he made of mounting and framing Matron Brown’s medals and memorabilia.

~ Lest We Forget ~

The reunited medal tally is now 265.

The Life & Times of Matron Sylvia Daisy Brown

Author’s Note: This post is considerably longer than usual as it reflects 18 months of research into Matron Sylvia Brown’s origin and life before her arrival in NZ in 1912. Apart from her nursing, nothing was known of life before nursing and very little remains after her death. To unravel Sylvia’s story from her birth in Yorkshire was a challenge. Trying to piece together the background of this enigmatic spinster who became the long serving Matron of Nelson Hospital, and the reason she remained in Nelson for the rest of her life, were mysteries I could resist to at least attempt to resolve.

Some of my conclusions are conjecture due mainly to an absence of any information to the contrary, and therefore I remain open to be corrected. They are my best guesses after gathering what information was available and marrying this together with Sylvia Brown’s time and place in England’s history and her circumstances at any given point in her life. To produce anything more definitive would require considerably more time to research than I have the time to spend on one case. I should also point out that while I have tried to present the information in a chronological sequence, some explanations cover longer periods of time (years) and have been inserted at that point to aid the readers understanding.

I invite any reader who spots an inaccuracy to please contact me. I am sure there is much more to Sylvia Brown’s life story than my humble attempt has been able to encapsulate, seventy years after her death.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

AWMM Cenotaph Profile

After receiving Sister Brown’s war medal from Constable Ben Wallbank, my start point for most medals to be reunited is the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s (AWMM) Cenotaph database where I found a very thin file for Sister Sylvia Brown among the New Zealand Expeditionary Force’s (NZEF) soldiers and NZ Army Nursing Service (NZANS) nurses of the First World War. This in itself was unusual as Sister Brown was never a member of the NZANS or the NZEF.

Having a basic knowledge of Sister Brown’s war service, the first noticable absence from her Profile Page was information and, what was there contained inaccuracies! Her date of birth was confined to a year only; one of the units she had served in was missing, as was one of the medals she had qualified for. Her post war employment record was incomplete and her military training was confused with her nursing training prior to enlistment, and so on. This did not exactly fill me with confidence to use this material. The detail had been added by museum staff so understandably may have been subject to transcription error.

Sylvia Brown’s original Cenotaph Profile page is reproduced below. Items in red indicate an error or incomplete detail that appeared at the time I viewed the page in 2017. I have omitted duplicated information to save space.

NAME: Sylvia BROWN (second name missing – Daisy)

Birth – Circa 1883 (incorrect – Dec, 1883)

Date of Birth – 1884 (incorrect – 02 December 1883)

Place of Birth – Essex, England (incorrect county – York, Yorkshire)

Identity

- FORENAMES: Sylvia

- SURNAME: Brown

- ALSO KNOWN AS: Sylvia Daisy BROWN (birth name = Daisy Sylvia BROWN)

- SERVICE NUMBER: B.28 (incomplete = 2/R–B/28)

- GENDER: Female

Civilian life

- ADDRESS BEFORE ENLISTMENT: Pre 14 September 1915 – New Zealand, c/- Timaru Hospital, Sth Canterbury, NZ

- POST WAR OCCUPATION: Matron (incorrect – Sister) at Waiapu (incorrect – Te Puia Springs) Hospital (Maternity Annexe), Waipiro Bay, East Coast, Gisborne

- RELATIONSHIP STATUS: Single

Service

WARS AND CONFLICTS

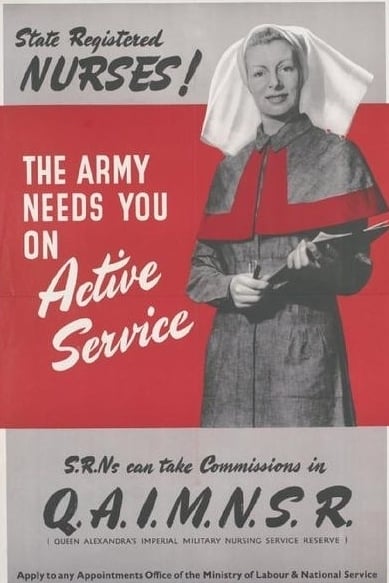

- ARMED FORCE / BRANCH: Army / Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR)

- WAR: World War 1, 1914-1919

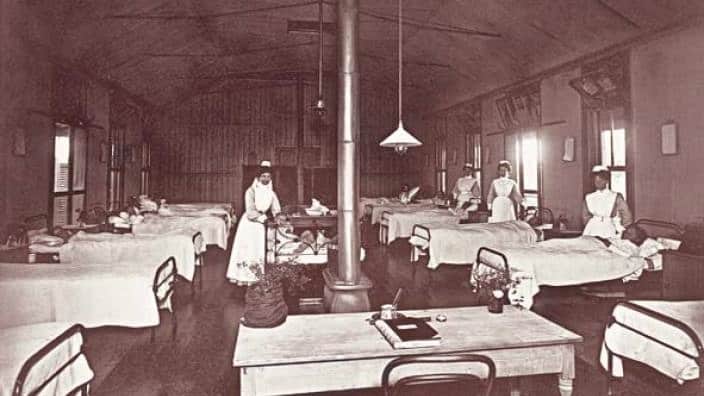

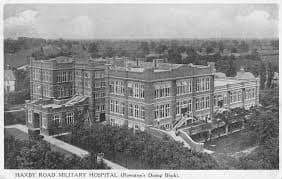

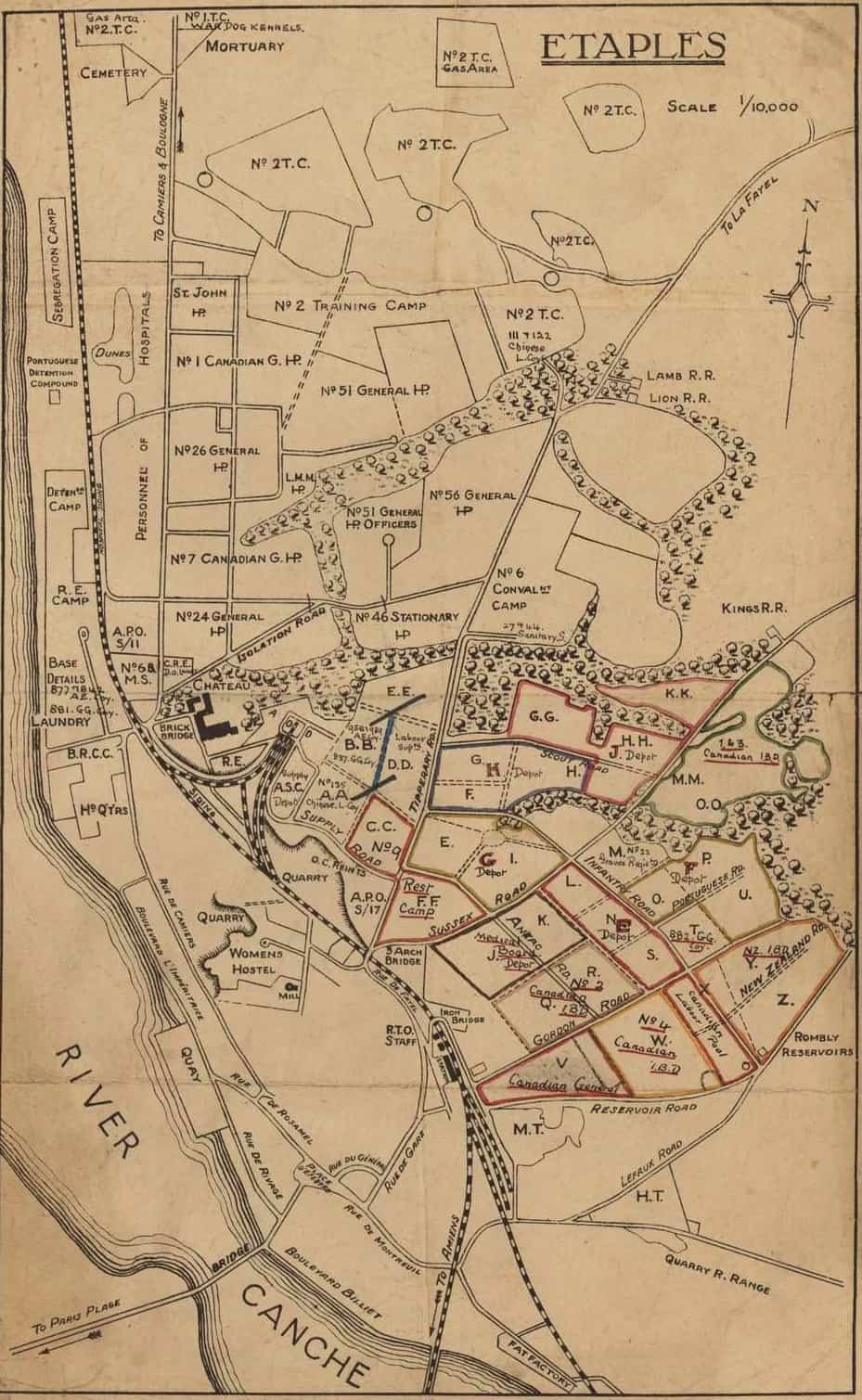

- CAMPAIGN: 1914-1919 Western Front – 2nd Military Hospital at York; No 6 General Hospital – BEF, France

- MILITARY SERVICE: 1915-1919

- MILITARY DECORATIONS:

MILITARY DECORATIONS

- MEDALS AND AWARDS: Victory Medal (British War Medal, 1914-18 not recorded)

TRAINING AND ENLISTMENT

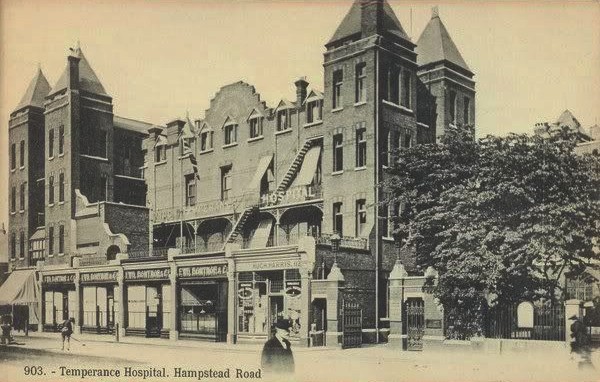

- MILITARY TRAINING: 1906-1908 – training at Temperance Hospital, London; 1909 – State Registered Nurse (SRN); 1912 NZ Registered Nurse (NZRN)

- ENLISTMENT: WW1 14 September 1915 – Ward Sister – Enlisted in England

- ARMED FORCE / BRANCH: Army / Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR)

- OCCUPATION BEFORE ENLISTED: 1912-1915: Ward Sister at the Timaru Hospital, South Canterbury, NZ

- AGE ON ENLISTMENT: 31 yrs

EMBARKATIONS

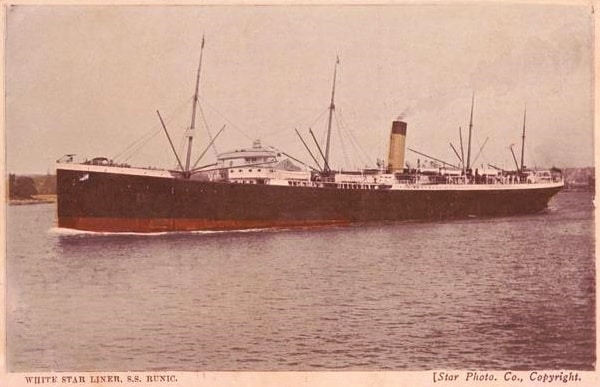

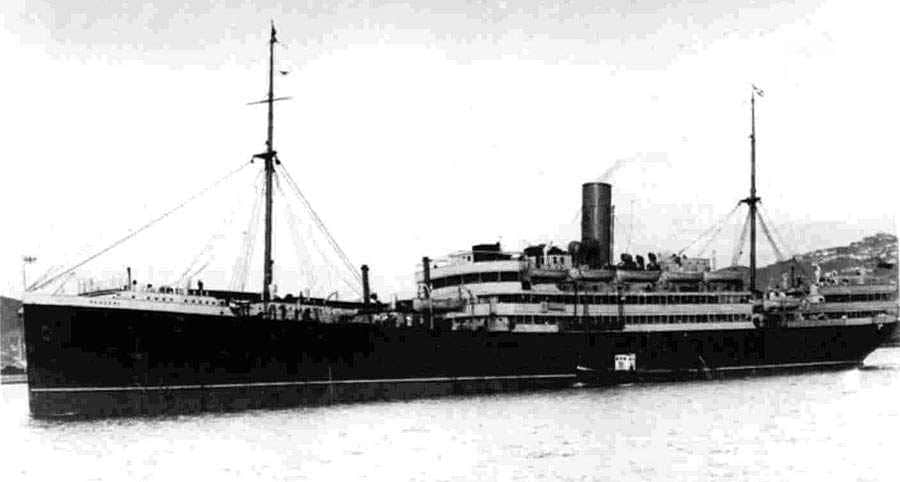

- EMBARKATION DETAILS: WW1 Sister – July 1915 – Left NZ on the ship ‘Remuera’ to England

LAST KNOWN RANK

-

- LAST RANK: WW1 7 April 1919 – Demobilised – (Acting Sister) Matron /Military QAIMNSR Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve

Biographical information

Sylvia Brown, also known as Sylvia Daisy Brown, did her nursing training at Temperance Hospital, London. Prior to enlisting she was a ward sister at the Timaru Hospital, South Canterbury, New Zealand. In July 1915 she travelled on the ‘Remuera’ to return to England and enlist for war service.

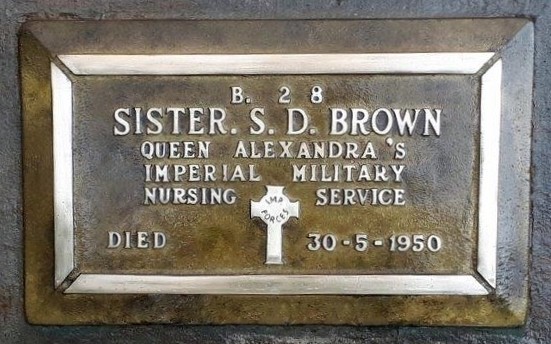

DEATH

- DEATH: 1950

- DATE OF DEATH: 30 May 1950

- AGE AT DEATH: 66 yrs

- PLACE OF DEATH: Nelson, NZ

- CEMETERY: Wakapuaka Cemetery, Nelson

- GRAVE REFERENCE: RSA Section Block 1 Plot 23

Why an NZEF File ?

From the outset of researching this case, I was beset with an information drought. When I opened the Cenotaph file of B.28 Sister Sylvia Brown – QAIMNSR, to my surprise it consisted of exactly nine pages which I found highly unusual for someone who had war service on the Western Front! As I read the contents I also wondered why it had been raised at all? The file contained only letters and receipts, to and from the War Office in England. These were related to Sister Brown’s pay and allowances after she had returned to New Zealand and so of little use. Apart from these there was nothing of her actual service.

I also started this research from a background of next to no knowledge of WW1 nursing services, be they New Zealand’s or any other country of the Empire. While the NZANS nurses on Cenotaph all had relatively comprehensive files of their service, not so Sister Brown. The only discernible difference I noted between Sister Brown’s file and the NZANS nurses files, was the difference in her regimental number – Sister Brown’s was 2/R-B/28 while all NZANS numbers started with 22/**** followed by a 1 – 4 digit number.

I could only imagine that Sister Brown must have been attached or co-opted as some sort of auxiliary military nurse. Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service [Reserve] (QAIMNSR) was not a unit I recognised however I was aware a number civilian hospital nurses had served with a variety of military hospitals during the war – perhaps she had been one of these?

Critical for me, there was no “Record of War Service” (RWS) in Sister Brown’s file which most NZANS nurse had in theirs. The RWS contains all personal information including enlistment documents which would have the details of date and place of birth, citizenship status, age at enlistment, parents, next of kin, rank, professional qualifications, education, medical specifications and inoculations, fitness etc, plus an all important employment summary (postings, promotions, attachements etc). It would also include any entitlement to decorations and medals.

A book entitled “All Guts No Glory – Nelson Tasman Nurses and Chaplains of World War One” by Cheryl Carnahan (Nelson 2015) proved to be somewhat more useful than Sister Brown’s Profile Page and file. It contained a short biography of Sylvia Brown’s nursing service in New Zealand, some basic information such as dates of birth and death, where she did her training, her war service and the places she had nursed at in New Zealand until becoming Matron of Nelson Hospital. Little however was made of her origins and pre-war life before coming to New Zealand, or after she retired – these were the parts of Sylvia Brown’s life that I hoped to shed some light on.

Sylvia Brown’s citizenship

I was interested to know that if Sylvia Brown was a nurse in a New Zealand hospital before the war, why she had apparently returned to England to enlist with the QAIMNS(R) and not the NZANS if she was keen to offer her services for the war?

Sylvia had been an accepted on to the Roll of New Zealand Registered Nurses (NZRN) in April 1912 after she arrived in NZ. At the time she travelled back to England, she was still a UK national as she had not yet qualified by time to become a naturalized New Zealander. Was this the reason she had not joined the NZANS? My research would suggest not, as being a NZ citizen at this time was not a prerequisite for enlistment in the NZANS or the NZ Military Forces (as it is now). I could therefore only conclude Sister Brown’s reasons for returning to England for war service must have been for purely personal/patriotic reasons.

Since I was about to write the story of Sylvia Brown and her war medal, I felt it important to present her life as accurately as possible and to try to fill the very large gaps of her life that nothing was known of. I believe I owed it to Sylvia Brown’s memory as a veteran, and to the successive generations of Nelson nurses, to tell Sylvia’s story in full as best as I was able to so they could have a full appreciation of exactly who Matron Brown was, as her photograph and medals would also be permanently on display in the Nelson Hospital.

Finding Sylvia Brown’s roots

Given the shortcomings of the available reference material about Sylvia Brown I had so far seen, I decided to discount it all and rebuild her life from scratch. That necessitated obtaining her QAIMNS(R) fil from the British Archives which would havesubstantially more accurate information if I was able to interpret it all. As a good number of documents in Sylvia’s file had been completed in her own hand, this gave me confidence the material would be accurate. This particular file also cleared up the question of why the Cenotaph / Archives NZ file named to Sylvia only contained post-war bumph.

By coincidence, one of the top (latest) entries of Sister Brown file was a request by her after the war, to the War Office, asking for a copy of her “Record of War Service.” According to the file notes, this she received in 1921 after being sent directly to her via the Waiapu Hospital Board, the administering body of Te Puia Springs Hospital in the Hawkes Bay where she was working at the time. Being a military file, if her RWS been sent care of the NZ Defence Secretary’s office as was normal procedure between Allied military forces and not directly to the person, a copy would have automatically been generated and archived in her NZ file before being sent to Sylvia. This is the kind of wartime / peacetime administrative challenge researchers are often faced with unravelling, usually by having to spend money!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

YORKSHIRE

Date and Place of Birth

Confirming when and where Sylvia Brown had been born was central to building her past. Hopefully this would also lead me to her family and an understanding what had prompted this life-long spinster and nurse to leave her ancestral home, emigrate to New Zealand, return to England and volunteer for war service, and then return to NZ to live out her life in Nelson, in relative obscurity Nelson?

Starting with her birth, the file immediately clarified a previous unknown – the date Sylvia was born. The file stated: 2 December 1883 (not 1884 as was recorded in other records), and her Place of Birth was confirmed as York. The problem with this however was that I could find no record of births in York for 2 December 1883? There was no Ancestry.com record of her birth, nor was she listed in any on-line records for the County of Yorkshire. I cross checked with the Yorkshire and All England Census records – again, nothing – Sylvia Daisy Brown simply did not exist? My default thinking in such circumstances is to suspect illegitimacy.

Not finding any reference to Sylvia Daisy Brown was highly unusual, particularly as Sylvia had been a spinster all her life. Unless she had been married or changed her name for some reason, she should have appeared at least once! The other deficiency that struck me reading her birth details was the lack of any reference to parents or family.

I would need to find a link between Sylvia’s birth and the existing Yorkshire census records if I was to find out who her mother, father, family and place of birth were, and to trace her movements before she enrolled for nursing. For the moment I was stuck!

Registration anomalies

From previous experience I have found that the registration of a child’s birth is generally not done immediately, nor even proximate to, a child’s birth date. Most families get around to it after some time has passed and so since there was no urgency in these years, registrations made up to six months after a birth was not uncommon. Within a single year, births, deaths and marriages were registered in the Quarter in which they occurred (more or less) – Jan-Mar, Apr-Jun, Jul-Sep and Oct-Dec. However if the registration was not recorded in the Quarter of the birth, then it would likely happen in the following Quarter. Given this delay, if a birth occurred during the Last Quarter of a year (as Sylvia’s did – 2 Dec 1883), the baby’s registration year would probably be done by the parents in the First Quarter of the new year, and this is exactly what I believe occurred with Sylvia‘s birth – born 2 Dec 1883, registered in the Jan-Mar Quarter of 1884. In New Zealand the same situation can and does happen today, but the occurrences are far fewer as the law requires a child’s birth to be registered within eight weeks of birth – a trap for the unwary!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Overview

It was clear from the above plus a cursory viewing of census, electoral rolls and NZ newspapers there was very little about this woman anywhere and that I was going to have difficulty finding accurate information from which I could base my search of Sister Brown’s early life in England. I started with her public nursing career records in NZ such a registrations and from here would work backwards to England. I gathered the available nurse and midwife registration references, and a couple of articles from NZ newspapers that related to Sylvia hospital appointments. These showed she trained at the London Temperance Hospital from 1906-1908, graduated in 1908 as a State Registered Nurse (RN) and Midwife. Leaving England in 1909, Sister Brown went to Australia for three years before emigrating to New Zealand in 1912. She had held a number of posts in NZ hospitals before WW1. Sister Brown returned to the UK. in 1915, enlisted into the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR) and served in both England and France for three and a half years, before returning to New Zealand in 1919. Sister Brown was appointed Matron at Nelson hospital in 1920, retired in 1937 and died in 1950. There was no indication whether she had ever became a naturalised New Zealander.

There was no obvious evidence she was (ever) married and appeared not to have had any family in New Zealand. There was nothing of any note about her in any of the Nelson newspapers of the day, or the history websites other than her appointment as Matron at Nelson. No death notice, or record of a funeral other than her date of death and the fact she had been buried in Nelson. A check of the NZ Army Nursing Service Association website to see if she had served with the NZANS at any time, also drew a blank. For a woman who had been Matron of Nelson Hospital for 17 years, Sister Brown proved to have been remarkably anonymous.

The early years in Yorkshire

The key to finding Sylvia Brown’s past was in her name. I had initially looked for any record that contained Sylvia Daisy Brown. There were several census and BDM records which made reference to various combinations of her first names Sylvia, Daisy and Brown such as Daisy Sylvia Brown, S.D. Brown, Daisy S. Brown etc, but none of these in the Yorkshire censuses were within the year range for Sister Brown. I then checked the nursing registrations since they also carried the address of each nurse at the time of annual re-registration. There were entries for a Sylvia Brown and several more for Daisy S. BROWN with the address, “c/o Mrs Lamond, Great Fishall by Tunbridge.” This was the nearest to Sylvia Brown’s full name I had come in any registration. What’s more the years of registration matched the years Sister Brown had undertaken her training at the London Temperance Hospital. I had found her! Back I went to the Yorkshire BDM records and censuses to try and locate the birth date and place of Daisy S. Brown.

Looking firstly for BROWN births that included combinations of Daisy S. Brown, Daisy Sylvia Brown or D. S. Brown, I consulted all Yorkshire birth, death and census records between the years of 1841 and 1901. In these I found only one entry which seemed to fit Sister Brown’s birth date. The 1891 West Riding of Yorkshire census showed that a “Frances BROWN (49), Lodging-house Keeper, and daughter “Daisy S. BROWN (7)” were living in the High Street of a village named Boston Spa. This meant that Daisy S. Brown would have been born in 1883/1884. But that was as far as it went – no other records for Daisy S. Brown?

Frances Brown’s address was listed as 54 Main Street, Clifford with Boston, Boston Spa which was near a Boy’s Preparatory School. The lodging-house was the boarding hostel for the pupils of the Prep School. I looked for evidence of a Mr Brown, presumably Daisy’s father but could not find any male named BROWN linked to Frances or Daisy Brown. A check of the Yorkshire Registry of births, Deaths and Marriages for “Brown” males in the area – nothing in 18901, 1891 or 1871 that related to Boston Spa, or the parish of Spofforth that Boston Spa was situated in.

I then looked for a birth record for Daisy S. BROWN – nothing, however I did find a birth record for Daisy S. MORRELL whose birth was registered at York in 1884. Apart from the Morrell surname, there was definitely some very coincidental elements to this find – same first name, same initials, location, and a birth year very close to Sylvia Brown’s stated birth date, 2 December 1883. Could Daisy S. Brown and Daisy S. Morrell be the same person?

The MORRELLs of Follifoot

Frances Morrell was well documented in the West Riding census over several consecutive years. They showed her family had been resident in the rural hamlet of Moor Side, Follifoot since at least 1841. Follifoot is situated in the parish of Spofforth in the West Riding of North Yorkshire, roughly midway between Harrogate and Wetherby. It is dominated by several features such as Spofforth Castle, Plumpton Rocks and the Rudding Park Estate. The nearest major city is Leeds to the south west.

Samuel and Mary Morrell (nee WELLS) were tenant farmers whose roots were in Pannal, just four kilometres from Follifoot. In 1851 Samuel and Mary were farming 110 acres in Follifoot, the farm now part of Rudding Park Estate which also includes the former Oakwood Estate once owned by the Brearleys. Frances Morrell, the second youngest child of nine, was born in 1842; her eldest sibling Rebecca in 1825 followed by Ann, Mary, Thomas Wells, Hannah, Samuel Jnr, John William and baby Sarah Morrell in 1844. Frances Morrell’s birth record showed she had been born at Knaresborough, about 11 km north of Follifoot and Spofforth which also sits on the fringes of Rudding Park. I located records for Frances, her parents and most of her siblings at Follifoot in every West Riding census from 1841 to 1871.

In tracing the Morrells I found that Samuel Morrell Snr had died in 1880 aged 77, leaving his wife Mary (81), youngest son John William (40) and Frances (39) as the only family members still living on their Follifoot farm (by then reduced to 23 acres). The 1881 census showed Mary Morrell had died (1883) which left only Frances (41) and brother John William Morrell (43) at home to manage the land. This was also the last time Frances MORRELL appeared in any UK census.

Sister Brown noted in her enlistment application that her nearest relative was “Robert Brearley Esq. – 1st Cousin and Guardian.” My next step was to find out how Sylvia was connected to Robert Brearley and since he had been her guardian, did this mean that she had no father, or no known father, or had perhaps had been orphaned or abandoned?

The BREARLEYs of Batley

A ‘guardian’ suggested Sister Brown had been in the care of one from an early age. On the face of it this seemed an odd congregation – the Morrells being a tenant farming family of limited means, and the Brearleys, a self made and highly successful family of influence and wealth made in the textile industry with and international export clientele in France, Germany, Belgium, the Americas and throughout the United Kingdom.

To find the some of the answers I would need to first reconstruct the Brearley family to find out where exactly the connection between the Brearleys and the Morrells occurred. In the period 1841 to 1911 there were numerous Brearley families mentioned in the Yorkshire censuses, the majority of whom resided in and around the town of Batley. In the 1911 census I found one Robert Brearley Esq. who was by occupation a “woollen manufacturer” and manager/owner of the massive Queen Street Mill in Batley – this was obviously Sylvia’s first cousin. Robert’s older brother Arthur assisted Robert with the running of the mill, and his two younger brothers, Henry and Thomas Percival Brearley, were employed as workers at the mill.

BATLEY and ‘Shoddy’

Batley is a very old town in the West Riding of Yorkshire. It was mentioned in the Doomsday Book in 1086 and was listed in the 1379 Poll Tax. The parish church, All Saints, was erected in the 15th century during the reign of Henry VI (1422-61).

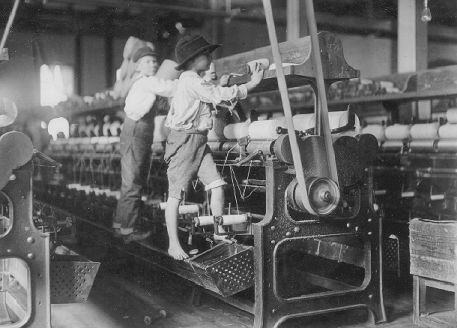

Batley became a major industrial centre as a result of the the woollen and textiles industry development following the invention of ‘shoddy’, a cloth made from recycled wool invented ion 1813 by Batley’s Benjamin Law.

Men in the 19th century generally owned one good or “Sunday suit” which was of the finest black broadcloth and worn with a white shirt and a black tall hat. At home the jacket was removed and the shirt and pants were covered with a blue apron. A suit lasted from 5 to 7 years. Week-day trousers of the working man were made of a large percentage of cotton cord.

‘Shoddy’ – The process involved grinding woollen rags into a fibrous mass and mixing this with some fresh wool. Law’s nephews later came up with a similar process involving felt or hard-spun woollen cloth, the product in this case being called ‘mungo’. The manufacture of shoddy and mungo was by the 1860s, a huge industry in West Yorkshire, particularly in and around the Batley and Dewsbury areas. It created a national and international demand for rags and waste wool, and made clothing much more affordable.

Shoddy came to mean ‘cheap and nasty’ almost certainly because of the American Civil War (1861–65). Recruitment of huge armies on both sides created an immense demand for uniforms, which some manufacturers struggled to meet (or exploit) with poor-quality shoddy. This led to stories of soldiers’ clothing falling to pieces after just a few days’ wear, or even in heavy rain.

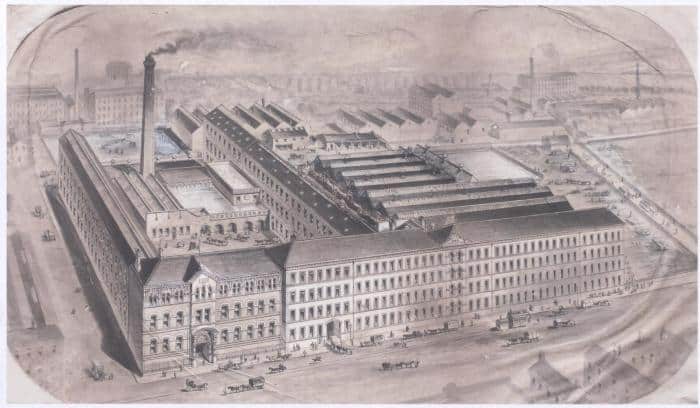

Queen Street Mill

A search of the social history of Batley and the woollen manufacturing industry in Yorkshire reveals that Robert Brearley (1808-1866) had started in the manufacturing industry after years of operating a weaving loom in one corner of the living room of his and wife Elizabeth’s cottage in Batley. He partnered with his brother-in-law Joseph Hall in taking over the Clerk Green Mill and turned its fortunes around. By the early 1850s trade was good and manufacturers were experimenting with different weaves. Robert had perfected a particular and lasting quality of ‘shoddy’ by blending materials which became much sought after. Robert Brearley was one manufacturer who is said to have made a great deal of money out of what were called “Marble goods” which enabled him to build a new mill. The foundation stone was laid on the first of March 1853 by his son Thomas (1835-1890). It was said that the mill was to be called The Marble Factory, but it is as the Queen Street Mill that it became known.

It was the quality of Robert Brearley & Son’s shoddy that set it apart from other producers. He had started exporting to Europe and the Americas which set the Brearley manufacturing industry on a path to expansion and wealth. Robert and Elizabeth Brearley had five girls and only one son, Thomas, who after his father died would take over the business but retain his name. Thomas’s and Hannah Brearley’s family fortunately was the reverse of his father’s fortunes in that he had four boys and one girl. The boys were all put to work in the business as the mill grew into a massive complex (above) whose primary product was ‘shoddy’.

The Brearley’s manufacturing empire was at its zenith 1880-1900 but lasted only two more generations before the family was out of the business. Thomas Brearley died in 1890 and second eldest Robert Brearley Jnr (1861-1929) took the helm along with his older brother Arthur. The two younger brothers, Henry and Thomas Percival Brearley initially had worked in the mills but later pursued other manufacturing interests. Robert Jnr continued to trade as Robert Brearley & Son until his death while on a business trip to Mentone in the south of France, in 1929. The mill went into liquidation six years later in 1935. It was eventually in the ownership of Jack Stross Ltd., but that too was to close in 1959.

The success of the Queen Street Mill and the production of shoddy by the Brearleys had spanned 80+ years. It not only made them wealthy and influential but each successive generation had contributed greatly to the growth and prosperity of Batley, both in terms of financial capital and employment. They had been major contributors to building the Batley Hospital, and the Batley Methodist Central (Zion) Chapel in the town square. Such was the Brearley influence that even the Chapel, in a nod to the family, was known by the town’s folk as the “Batley Shoddy Temple.”

The BREARLEY – MORRELL connection

When Thomas Brearley had married on 27 May 1856 it was to a Moor Side girl from Follifoot named Hannah Morrell (1835-1899), the elder sister of Frances Morrell (1842-1899). Thomas had built the Oakwood House in Batley on a large estate that now forms part of the Rudd Park Estate and which happens to have on its boundaries to the NW, NE and SE, the villages of Pannal, Spoffoth (Follifoot) and Boston Spa.

So what did this have to do with the birth of Daisy Sylvia Brown, aka Sister Sylvia Brown? The first clue came in the 1871 census. Residing at Oakwood House in Batley was Thomas BREARLEY, the owner of the Queen Street Mill, his wife Hannah and sons Arthur, Robert (10), Henry and Thomas Percival Brearley. Also at the house was “Frances MORRELL (28) – Single – Sister-in-Law.” This entry obviously proved that Hannah was Frances’s sister – family connection confirmed. What it also meant was that should Frances Morrell ever have a child in the future, the young 10 year old Robert Brearley Jnr (later owner/manager of the Queen Street Mill) would be that child’s first cousin.

Daisy S. BROWN or Daisy S. MORRELL ?

Sylvia Brown had stated in her military enlistment application that both parents were “Deceased.” Whilst the identity of her father remained unknown, the York Death Register recorded the burial (and presumably death) of one Frances MORRELL (59) in the Apr-Jun Quarter of 1899 at Wetherby. That also accorded with Frances Brown’s age in the 1891 Census of Boston Spa, give or take a few months.

In the absence of a documented marriage for Frances BROWN, or any apparent existence (or death) of Daisy’s father named BROWN, I believe it is safe to conclude that Daisy S. MORRELL and Daisy S. BROWN, ergo Daisy Sylvia BROWN, Sylvia D. BROWN, and Sylvia BROWN are all one in the same person. As I continued down this and explored her wider family connections, the evidence became overwhelming.

NOTE: for the purposes of continuity, I will refer to Sylvia Brown by her birth name DAISY from this point until she assumes the name SYLVIA in preference to Daisy, circa 1909.

Who was Daisy’s Father ?

The most pressing of question was whether Daisy’s birth had been legitimate or illegitimate? To answer this I needed to find out whether or not there was a “Mr Brown”, or perhaps a marriage record of someone else to Frances Morrell, before or after Daisy’s birth. If I found a husband (or man) named Brown who could be clearly linked to Frances and Daisy’s birth, the possibilities proffered below could be ruled out. But I could not and became even more convinced that Daisy Sylvia Morrell [Brown] was illegitimate.

With the information I had gathered to date, I theorised over Daisy’s paternal possibilities by looking closely at Frances’s status, age and location between 1872 and March-April 1883 when Daisy would have been conceived, and .

Frances Morrell was born about 1842, being a Brearley ‘extended family’ member by marriage (via her sister Hannah Brearley, nee Morrell, her presence at Oakwood House in 1871 suggested she was more than a “Visitor”, possibly living there to assist her sister Hannah in some fashion, or perhaps she was employed at Oakwood in some domestic capacity, or even working for her brother-in-law Thomas Brearley in his Queen Street Mill? It would have been too far to travel from Follifoot on any regular basis, to any from any other type of work beyond what she was doing on the farm at Follifoot.

To put Frances Morrell’s status and residential circumstances into perspective at the time Daisy S. Morrell [Brown] was conceived (Mar-Apr 1883), Frances was single and of mature age, in fact at 41 years of age in 1883 she was more than middle aged when one considers the average age at death for women was around 60 at this time. It could also have been that Frances being aware of her age may well have wished to have a child before she was very much older – her biological clock was ticking!

Frances had ample opportunities for a ‘liaison’ with any number of available males either in Batley, Follifoot or latterly in Boston Spa. At Oakwood there were her four barely eligible Brearley male cousins (all younger than Frances) who worked at their father Thomas Brearley’s Queen Street Mill and still living at Oakwood House. There were also the two families of staff who maintained the Oakwood estate and who occupied two separate houses within estate; three of the males were of age and eligible. The Queen Street Mill itself employed around 400 workers (mainly males) and that was quite apart from many more who worked in the more than 70 mills of varying sizes that populated Batley. The expansion of cloth manufacturing and textile processing in Batley had seen the population go from a sedate 7,000 in 1841, to 21,000 in 1851 and by 1891 it had exceeded 128,000.

Following the death of Samuel Morrell in 1880, and their mother Mary Morrell in 1883, Frances (41) and her old brother John William (43) were the sole remaining Morrell family members living at Follifoot. It is unknown when exactly Frances went to live in Boston Spa but to recap, the first census record in which she appeared as the Lodging-house Keeper was 1891 – Frances ‘Brown’ as she then was, was 49 years old and daughter Daisy ‘Brown’ was 7 years of age.

A less likely hypothesis but one not to be totally dismissed was that Frances became pregnant to a person known only to her which could have been from any location. She may have remained at Follifoot to have the baby, or had simply moved away at an appropriate time to have her baby, perhaps to a convenient village (like Boston Spa) where she was unknown, secured a position as Lodge-house Keeper, had her baby, and continued to live there without any undue attention from anyone.

In the absence of proof positive, I resist the temptation to speculate any further on Daisy’s paternity. Suffice to say I could find no definitive record that would prove the identity of Daisy S. Morrell’s father. My personal belief is she had been born illegitimate.

Where was Daisy S. MORRELL born ?

My conclusions here resulted from information pertinent to establishing where Daisy had been born:

- The YORK Registry shows that Daisy S. Morrell’s year of birth was registered at York in the first quarter of 1884. This is proximate to Sylvia D. Brown stated date of birth of 2 Dec 1883. This of course did not automatically mean the birth had occurred in York. York was the largest city in the West Riding and therefore the centre for the county and parish administrative records such as the registrations of births, deaths and marriages.

- A familial connection existed between the Morrell and Brearley families via Hannah Brearley (nee Morrell).

- Frances MORRELL was ‘unmarried’ in 1881, and no longer living at Follifoot by 1891.

- Had Frances Morrell been married when she had Daisy, both parents would have been recorded for the birth, an address, and possibly a separate record of baptism – none of these I was able to find which again reinforced my belief that Daisy’s birth was illegitimate.

- Frances [Morrell] BROWN and daughter Daisy S. BROWN were living in the High Street at Boston Spa in 1891 according to the census; this was their first appearance in public records under the surname of BROWN.

- Frances [Morrell] BROWN remained in Boston Spa until her death eight years later (presumably at Boston Spa). The York Registry records only her burial in 1899 at Wetherby, just 2km from Boston Spa.

- Frances BROWN’s death was registered in her own name, Frances MORRELL and not BROWN.

Conclusion: Again, in the absence of a definitive birth record or any other record after the 1891 census that might bear her or Frances [Morrell] Brown’s name, it is impossible to name the location of Daisy’s birth; York was the only place mentioned in connection with her birth, the place her birth was registered in 1884.

Why BROWN and Boston Spa?

In considering this question I gave weight to the proposition that a pregnant Frances Morrell was assisted in her circumstances possibly at the insistence of her sister Hannah Brearley. Boston Spa was a safe and trusted environment sufficiently far enough from Follifoot, Spofforth and Batley where she was well known, to avoid as far as possible any scandal or impact on should the father be known. By providing Frances with a residence and an income as the Lodging-house Keeper of the Boys Prep School in Boston Spa, she could sustain her either before, or after the baby was born, in anonymity. By also adopting an unassuming name such as “BROWN”, the presence of a baby/child with her could be easily explained away by a “widow”, Daisy’s aunt, her step-mother, grandmother or similar but only in a place she was unknown.

Knowing what I now do of the personalities and future events that affected this family, in retrospect I considered the following hypothesis as a credible possibility:

- It is 13 kms between Follifoot and Boston Spa which even in those days was not an unreasonable distance for people who may have known Frances Morrell, to travel either on foot or by horse/coach and whom she may meet unexpectedly in the street. Follifoot was rural and sparsely populated while Batley was a town approaching city status, such was its prosperity and speed of growth.

- On the other hand, Batley is 51 kms from Boston Spa, a distance which would have provided a much greater buffer likely to prevent routine contact with people Frances knew or associated her with the Brearleys. A Lodging-house Keeper’s position, being one surrounded by children of varying ages including the children of women staff members employed at the Lodging-house, thereby providing a natural mask for any maternal indiscretion. As the child grew it would simply blend into the occupants of the Lodging-house and be seen as just another pupil or one of the staff’s children.

Granted, this is conjecture but certainly it would be an effective means of deflecting any unwanted attention or a connection to any person who stood to lose their reputation or name, should that person be linked to an illegitimate child of their making? This still doesn’t answer the question of exactly who Daisy S. Brown’s father was, but I fear it is as close to the truth as I have the time to find.

With this information, I must leave you to draw you own conclusions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

BOSTON SPA to TILDONK

Early education

Having dealt with the possibilities of Daisy’s origin as far as is possible, the next phase of her life is equally mysterious and interesting, again with more questions than answers. Growing up in Boston Spa, it would have been reasonable to assume that Daisy’s first couple of years of infant education may have occurred while her mother was the Lodge-keeper at the Boston Spa Prep School. Class sizes for the infant boys would have been more than capable of absorbing one infant girl belonging to the student’s ‘house mother.’ The alternative was a private tutor. There were numerous small schools in Boston Spa conducted in the houses of the educated few. Small classes (5-7 children) were provided as an act of benevolence by some to educate the children of the poor who could not afford to pay for education – Daisy could have gone to any of these?

European school days

Whilst I could not find any particular evidence of Daisy’s infant education in Boston Spa (if any), I was able to trace her later schooling history from entries she had made in her QAIMNSR enlistment application. In answer to the question of where she had been educated, Daisy had written: “Ursuline, Tildonk Brussels; Breslau, Carlowitz, Germany; The College. Boston”

On the face of it, a Catholic schooling in Europe seemed a most unlikely start to the education of a seven year old from Follifoot/Batley/Boston Spa, possibly illegitimate, fatherless, a working mother of limited means (Lodging-house Keeper), and from presumably a Methodist family background (Morrells and Brearleys). Travelling the 700 kms to Belgium would have been a substantial expense and which undoubtedly would also require a chaperone to accompany Daisy, plus accommodation and travelling expenses for the journey (rail, ship, rail) and that was before her tuition and board was paid for. Someone of means I imagine must have had a hand in making this happen. A cousin perhaps?

The Ursulines

Not having the remotest clue what “Ursuline, Tildonk” might be (other than it was in Brussels), I asked ‘Mr Google’ for assistance. Tildonk is a village in the Belgian province of Flemish Brabant, near the borders of Germany and Poland.

The Ursulines refers to a number of religious institutes of the Catholic Church which still exist. The best known group was founded in 1535 at Brescia, Italy by St. Angela Merici (1474–1540) for the education of girls and care of the sick and needy. Their Patron Saint is Saint Ursula. The Ursulines are divided into two branches; the monastic Sisters of Order of St. Ursula (O.S.U.), among whom the largest organizations are the Ursulines of the Roman Union. The other branch is the Sisters of the Company of St. Ursula, who followed the original form of life established by their founderess. They are commonly called the Angelines.

Tildonk Convent School

Both the Ursuline Convent School and Church in Tildonk were founded around 1818 by Pastor John Lambertz, a benevolent Belgian Catholic priest who saw the need for educating girls who had no means of education, literacy, or catechesis. Pastor Lambertz very much wanted to do something for them and consulted with other priest. In the end he started a small school in, as if by divine intervention, a stable with three young ladies between the ages of 21 and 23 who had begged him to take them in as they were devoutly intent upon becoming Nuns. They became the three original Ursuline Sisters of Tildonk. As well as providing a benevolent education in the name of charity and succour to the poor, sick and afflicted, a commitment to the faith and spreading the ‘Word of God’ were equally important parts of the Sisters’ education and ‘repayment’. The Convent School later took in boarders from the ages of 5-18 who were in the main, daughters of British servicemen whose parents wanted them to have an education that was not disrupted by the frequent postings military personnel were subjected to.

Breslau–Carlowitz, Germany

In 1901, 112 years after the French Revolution, the French Parliament voted in favour of a ‘Law of Association’ which gave the signal for the persecution of religions and priests. The Ursuline Sisters were also not immune from this persecution. Together with the priests, the Ursulines were forced to abandon their schools and religious institutions and leave their homeland, by a hostile French Government who had driven them from their Convent and School in Bouloigne-sur-Mer and had passed laws that made it impossible for the Sisters to continue their work of Christian Education anywhere in France. This flowed northward and the same occurred in Belgium. The Ursulines was just one religious order thrown out of their houses, and their properties confiscated after the closing of their institutions. The majority of the Sisters and students in the Tildonk Convent School, fled north to another Ursuline school for the ‘higher education of young ladies’ in the city of Breslau, Germany. Previously a Polish territory, Breslau bordered the Polish city of Carlowitz which had been taken over during the days of an expanding German Empire.

After WW2, Breslau was restored to Poland and the two cities combined to become Breslau–Carlowitz (Wrocław-Karłowice as it is now known, or just Wrocław) and is administered as a single city by a Polish administration.

The Tildonk Convent School in Brussels was reinstated after the Revolution and steadily grew, both in numbers and facilities. The School has been steadily enlarged over the 200 years it has been operating, into the grand facility it is today that rightly celebrates a status among international schools that is second to none in Europe. The Roman Catholic Ursuline Sisters can be found in most countries of the world today where they continue to teach and help the less fortunate, whilst spreading the ‘Word of God’ and of their order.

“The College.Boston”

The last place of education Sister Brown had attended was “The College.Boston” (as it was written in her application). I could find no current or historical reference to “The College” or a “college” of any sort in the village of Boston Spa, the town of Boston in the adjacent county of Lincolnshire, or for any other school Yorkshire school past or present that either had a college, or used the word “college” in its title? My conclusion at this point was that Daisy must have finished her education at that the only well known college of that name, the very old and highly regarded Catholic institution of “Boston College” in Massachusetts, USA (which is what Google invariably opens to).

Daisy’s education by the Ursuline Sisters had been underpinned by Catholicism and an ethos based upon charity and compassion for the poor. Boston College MA caters for such streams of learning, and by departments that offer specialist professional development for those wishing to have careers in medicine, nursing, religious studies and in the church institution, governance, charity and the like – it seemed to fit the kind of profile that was evolving for Daisy and a logical extension to that which Daisy had learned at Tildonk and Breslau (possibly as a future Ursuline Sister or a Daughter of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul; perhaps also a contributing reason why she had chosen to remain a spinster?).

I had looked for every possibility of there being a “Boston/Boston Spa” college, high school, anything with that name in England. The only college long associated with Boston Spa was Wharfedale College ** which was an all boys’ school, so that was ruled out. I did find another “Boston College” in Ireland which raised my hopes. It would most certainly have been a Catholic institution however I quickly learned that this was actually an international extension of the Boston College in Massachusetts, USA. There was no evidence to support Daisy’s attendance at either of these schools.

Note: ** The former Wharfedale College is now the Grade II-listed (historic) Wharfedale Hall on Boston Spa’s High Street, the rear of the property sits on the banks of the Wharfedale River. In the 1850s, a second natural spring in Boston Spa (the reason for its name) was found on the present site of Wharfedale Hall. A company was formed to build a modest hotel, baths and assembly rooms over the spring however the grandiose plans that resulted saw the company bankrupted before the hotel was opened. The building subsequently became a boys’ school, Wharfedale College until is was taken over in 1939 by Notre Dame Girl’s School from Leeds as their wartime school. It was returned to a splendid residence, Wharfedale House, after the war – hence its current name.

St John’s – Boston Spa

I had a gut feeling that somehow Boston Spa and “The College. Boston” that Daisy/Sylvia had written down were somehow linked. Had she gone to the American Boston College, I felt sure she would have written “Boston College. USA” or something similar.

I searched for historical references to education in Boston Spa but found very little of any use – mostly relating to contemporary education. I then happened upon a 2008 newspaper article that reported the up-coming demolition of a former school building in Boston Spa. The building had originally been part of a school called the “Deaf and Dumb School” which I later learned had been re-named several times over its first 50 years – originally St John’s Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and then St John’s Catholic Deaf and Dumb College, St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf and Dumb and finally St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf, ** the name it retains to this day. Web searches of these names produced several useful results and took me first to a Catholic Priest from Belgium and then to Sheffield in North Yorkshire.

Note: While the School’s official name was/is St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf, it was referred to by past pupils and the deaf community as just “Boston Spa” as it is easier to lipread. “Boston Spa” was also the first school in England that used a sign language other than British Sign Language, namely Belgian Sign Language,/ which was introduced from Brussels by the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. St Vincent’s School for the Deaf at Tollcross in Glasgow, also taught by the Daughters of Charity, had previously used Irish Sign Language.

The Belgian Priest

Monsignor Désiré Pierre Antoine de Haerne (1804–1890) was a Belgian priest and one time Director (1856-1869) of the Royal Institution for Deaf Boys (and Dumb Girls) in Brussels, Belgium which had been founded by the Sisters (ka Daughters) of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul for girls who were deaf, dumb (mute) and blind. This inspired his lifelong interest in working with the deaf and and abiding concern for those children, generally of the poor, who without any education would be unable to support themselves by getting work when they were older. The success of the “deaf and dumb” school in Brussels where he had developed programs and trained the first two deaf English girls in 1869, encouraged him to take the concept of a school for the “deaf and dumb” to England. The first school was established in 1870 in a rented cottage at Handsworth, Woodhouse, Sheffield in South Yorkshire. The purpose was to teach deaf children, both boys and girls, to read and writing, and some hand skills to enable them to find work.

When Mons. de Haerne opened the Handsworth cottage school as St John’s Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, it had the capacity for accommodating 12 resident students. When the roll reached 41 by the end of 1874, the Monsignor sought a larger premises. With the help of the Bishop of Leeds and generous donations, a place was eventually found in the form of a converted house in Boston Spa which had formerly been the “Boston Spa College”, by then a defunct school for gentlemen’s sons.

Re-named St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf it was relocated from Handsworth in 1875 to 27 Church Lane in Boston Spa, West Yorkshire. The school opened in the same year initially with four deaf and dumb pupils. Monsignor de Haerne with the help of two Daughters (Sisters) of Charity of St Vincent de Paul who had bought from Belgium to assist him with the school in Handsworth, also ran the new school with the same Vincentian Family ethos. This school was the predecessor of a much larger school which evolved over the next fifty years into a fully fledged, purpose built school for deaf-mute children who had to be a minimum of seven years of age, of sound mind and capable of instruction, many of whom were boarded at the school, some permanently. Inmates typically stayed at the school for six years. The school flourished and expanded under the management and instruction of the Daughters of Charity, accepting children from every corner of the UK. New areas were used as workshops where the boys learned tailoring, shoe-making, carpentry, bookbinding and printing, while the girls learned cookery and household work, gardening, needlework and later, typing.

For almost a century and a half, thanks to the foresight and inspiration of Monsignor Désiré de Haerne, the Daughters of Charity have continued to apply their Vincentian Family ethos at St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf in Boston Spa, which will celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2020.

With this information, I had a moment of clarity re Sister Brown’s reference to “The College.Boston” – the references to Boston Spa College and St John’s Catholic Deaf and Dumb College, Boston Spa known by locals as “The College” and the use of “Boston Spa” by former pupils to refer to the College, now made perfect sense. Sister Brown’s reference to “The College. Boston” in her enlistment application was simply a short/corruption of the name used (probably used by the locals) to reference St John’s Catholic Deaf and Dumb College. The College was as mentioned before referred to as just ‘Boston Spa’ by former deaf and dumb pupils for its ease of lip reading. Add to this the fact “The College” had also been situated in the former “Boston Spa College” building, there was sufficient evidence amassed from all the references to the “deaf and dumb” school in Boston Spa for me to draw a conclusion as to which school Daisy had attended – St John’s, ergo “The College.Boston Spa.”

It was very possible that Daisy’s continued education was influenced by the Mons. de Haerne and the Daughters of Charity either before or after she had returned from Belgium. There is also the distinct possibility Mons. de Haerne had singled Daisy out as a potential tutor, having met her on one of his frequent visits back to Brussels from where he managed all his deaf and dumb schools. As a Catholic priest very well known in Brussels, undoubtedly he would also have had close contact with Ursuline Sisters and the Convent School at Tildonk. Mons. de Haerne’s need for tutors in his expanding school who were conversant with the Catholic Daughters of Charity ** education methods, language and ethos would have made Daisy Brown a prime candidate to be employed at St John’s, and the bonus was she actually came from Boston Spa! This the Monsignor had done previously with two deaf English girls whom he took to Belgium to be educated as tutors, both of whom once suitable skilled, returned to Boston Spa as tutors at the then St John’s Institution for the Deaf and Dumb.

To that end, it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Mons. de Haerne could have also facilitated Daisy’s chaperoned travel and entry to Tildonk on the understanding she would be schooled at the international Convent School and if he results were suitable, then be trained under the guidance of Mons. de Haerne to be a tutor at St John’s when she returned to Boston Spa?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In light of the above, I warmed considerably to the idea that Daisy’s Brown’s Aunt Hannah Brearley (on behalf of her sister Frances), together with her son Robert Brearley Jnr, who was already in the starting blocks to take over the mill from his ailing father Thomas, somehow had been involved in the decision for Daisy to go to Tildonk. It would also not have been beyond the Brearleys influence or benevolence to financially “assist” Monsignor Désiré de Haerne with building works required for his recently relocated St John’s school to Boston Spa, in return for his assistance with placing Daisy at Tildonk Convent School, and with the prospect of employment as a tutor thereafter, should she prove suitable? These were all possibilities that are reflected further on in the story which are necessary to recall for drawing a feasible conclusion on how Daisy Brown’s life unfolded.

Regrettably, nothing I found could either confirm or deny any combination of these propositions – but again, the answer I believe lies somewhere within.

Note: a minor point to note is that after Sister Brown returned from France prior to her demobilization, she requested a train travel pass to Glasgow before she left England in December 1909 – could this have been to visit some of her former colleague Daughters of Charity that were resident tutors at the St Vincent’s School for the Deaf at Tollcross? There was another reason for a visit to Glasgow which is revealed a little further on in this story and linked directly to a lady by the name of Wilhemina Hay Lamond, aka Elizabeth Hay Abbott.

Return to Boston Spa

Daisy returned to Boston Spa from the Breslau-Carlowitz Ursuline school in Germany at about 14 or 15 years of age (1898/1899). She had proven herself to be a very capable scholar and was fluent in both French and German. With this background she would have been eminently suited to being guided as a future tutor by the Daughters of Charity at the St John’s school. Whatever the case, apart from the death of her mother Frances in 1899, there is no record of how exactly Daisy spent the years 1900 to Dec 1904 other than we know now she had applied to attend the Nursing School at the London Temperance Hospital starting in 1905.

There is one other family that featured in Daisy’s life before this time which only became known once the notes in her military file had been deciphered to reveal the identity of Daisy’s mysterious references to a “Mrs Lamond.” This will become apparent a little further on in this saga.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A NURSING CAREER

London Temperance Hospital (LTH)

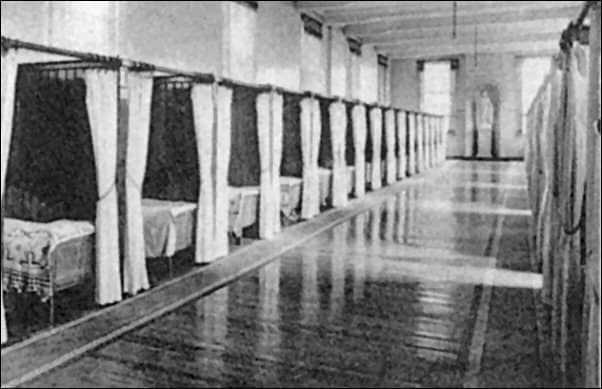

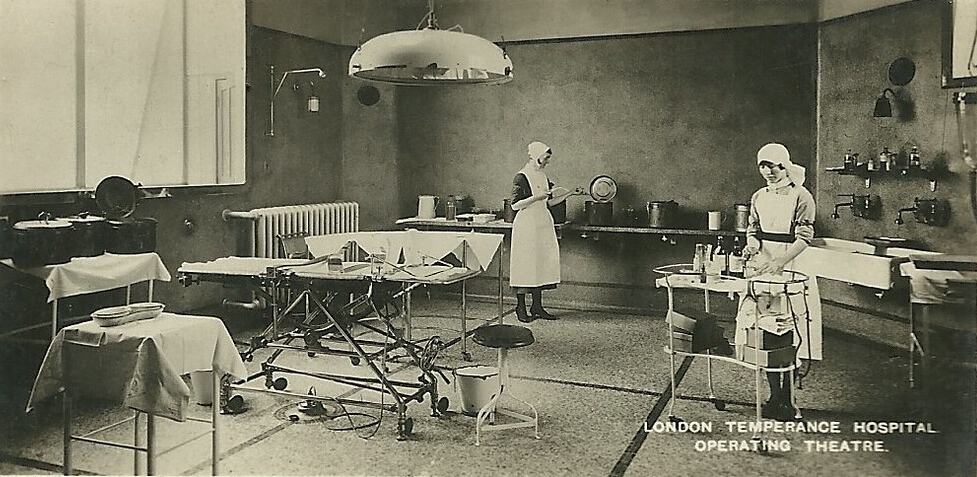

In January 1905 Daisy Sylvia Brown (21) enrolled as a Probationary Nurse at the Nurses Training School, a hospital department within the London Temperance Hospital (LTH) in Hampstead Road, Camden. The LTH was re-named the National Temperance Hospital (NTH) in 1932.

The London Temperance Hospital opened 6 October 1873 as an initiative of the National Temperance League and was managed by a board of 12 teetotallers. Under its rules, the use of alcohol to treat patients was discouraged, but not outlawed: doctors could prescribe alcohol when they thought necessary for exceptional cases. At the time Daisy enrolled, LTH was under the control of Matron Annie Isabel Richardson, a career nursing sister who was greatly respected and very well liked by her Probationary Nurse charges, and as it happened, was someone who Sylvia would call on for assistance in the years to come. There is no known reason why Daisy chose to go to the London Temperance Hospital for her training – most major hospitals had their own nurse’s training programmes and could issue a certification for having acquired the requisite experience as a nurse (and midwife) after three years on the job.

“Temperance” itself may have been an influential factor – whilst not knowing if Daisy had been exposed to then ‘demon’ drink via her mother or other family members, the LTH at the time Daisy enrolled had embarked upon ground breaking medical treatments by removing the widespread practice of treating most patient ailments with copious quantities of alcohol, with the exception of those ailments that had shown proven benefits from alcohol consumption. Perhaps it had also been the impact of her Catholic education with Ursuline Sisters that had influenced her to choose an establishment that was free from alcohol. Temperance was certainly a theme in the Convent School’s ethos and teachings.

Whomever paid Daisy’s fees to attend the training at Tildonk is also unknown. Being her “1st Cousin and Guardian” Robert Brearley may well have paid for this. Given the fees were initially minimal in return for spreading the ‘word’ and undertaking charitable works, it is unlikely there would much to pay. As the school gained popularity internationally, the fees went up accordingly. Apart from the Brearleys who may have funded Daisy for their own particular reasons, one other possibility was that the Lamonds may have paid – these folks we shall meet a little further along in the story.

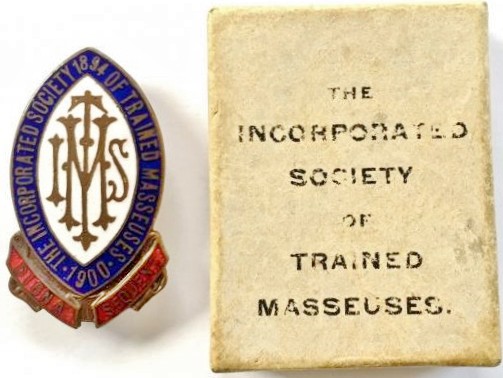

In April 1908 after two years training, Probationary Nurse Daisy Brown duly gained her London Temperance Hospital Certificate which was the prerequisite for sitting the State Registered Nursing examinations. These she passed successfully and as a now qualified Staff Nurse, Daisy’s name was entered into the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Roll as No. 11864, thereby also entitling her to use the post nominal letters of “RN” – Registered Nurse. A further nine months of specialist training followed for her Midwife’s qualification. After passing the Central Midwives Board (CMB) Certificate in Midwifery, Staff Nurse Daisy Brown’s name was entered on to the UK Midwives Roll as No. 27896 on 15 February 1909.

Important Note: At no time did Daisy Sylvia MORRELL ever legally change her surname to Daisy Sylvia BROWN or to Sylvia Daisy BROWN. Whilst she was required to use her first two names (the order was immaterial) as recorded in the York Registry, for all legal documentation, she remained “Daisy” for the duration of her nursing training. From the time Sister Brown left the London Temperance Hospital at the end of 1908, thereafter she only ever referred to, and signed, herself as Sylvia Brown or Sylvia D. Brown. For the sake of continuity, it will be to either (Sister) Sylvia Brown or Sylvia that I shall refer to from here on.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The LAMONDs

One of the things that prompted me to try to find out Sister Brown’s origin and back story was that at no stage in any of her documentation had she ever made mention of her family, apart from her “1st cousin and guardian” Robert Brearley. There was also the series of mentions of a “Mrs Lamond” in both her nursing training and military service records, who invariably had been quoted as Sister Brown’s point of contact and address whenever she was in London. The address was recorded thus: “C/o Mrs Lamond, Great Fishall near Tonbridge.” This deepened the mysteries that seemed to surrounded her early life.

Tonbridge (or Tunbridge Wells as it is now) is about 80 km south east of London. The first occasion Mrs Lamond was cited had been in Probationary Nurse Brown’s Nursing School application. The next reference to Mrs Lamond was in the 1909 UK Midwives Registration Roll, and again in Sister Brown’s QAIMNSR enlistment application, both as her point of contact while in France and as her leave address whenever Sister Brown returned to London (on three occasions). Last, Mrs Lamond had invariably had been referenced as Sister Brown’s address while she undertook a course of massage training in London after the war in 1919.

I looked first for any traces of Mrs Lamond at Batley, Boston Spa, Follifoot, Tonbridge, Great Fishall and the surrounding counties. Having found only a couple of entries for a Mr Andrew Lamond (Retired) at Great Fishall, Tunbridge, there was no mention of a Mrs Lamond. My first inclination was to question whether she had died, or perhaps was no longer with Mr Lamond, if indeed he was her husband?

The number of references to Mrs Lamond suggested to me that Sylvia had known her for quite some time and was a trusted person in Sylvia’s life. As for any mention of staying with Robert Brearley Esq., her “1st Cousin and Guardian”, there was no evidence to show she had stayed, or ever intended to stay, with the Brearleys at any time.

Mrs Lamond and the RMC

The breakthrough came as a result on an entry in Sister Brown’s records. I found a single variation to Mrs Lamond’s usual address of “Great Fishall near Tunbridge.” In a letter dated October 1918 that Sister Brown had submitted to Matron-in-Chief QAIMNS, Mrs Bechley at the War Office, whilst on sick leave in London, Sylvia had advised Matron Bechley that her address would be: “C/o Mrs Lamond, 36 King Square, Finsbury, London C.” (Central), the place she could be contacted for instructions regarding her post sick-leave employment with QAIMNSR.

A search of the 1911 London census and a Business Directory revealed that the address in King Square was a ‘Home of Service’ situated next door to St. Clements (formerly St Barnabas) Anglican Church. The ‘Home of Service’ was headed up by non-other than – “Mrs Lamond” (no initials or first name given!). A ‘Home of Service’ was part of a benevolent charity with royal patronage (the Queen Alexandra) that provided accommodation and birthing assistance (midwives) for London’s poor and destitute mothers and mother’s to-be. Many women (and wives) of the well heeled London gentry busied themselves with charity work to give them a purpose whilst they enjoyed their privilege, the most popular charity to serve being the Royal Maternity Charity. Mrs Lamond (then aged about 60) had become involved with the RMC after moving to London.

Royal Maternity Charity (RMC)

Founded in 1757, the Royal Maternity Charity was originally called the ‘Charity for Attending and Delivering poor Married Women in their Lying-in at their Respective Habitations’, later known as the ‘Lying-in Charity for Delivering Poor Married Women at their Own Habitations’ and finally as, the ‘Royal Maternity Charity for Delivering Poor Married Women in their Own Habitations’.

The Charity offered a service to ‘sober and industrious’ married women ‘destitute of help in time of labour’. It supplied them with medicines, provided midwives for ‘common cases’ and surgeon accouchers (male ‘midwives’) or physicians for more ‘difficult cases’, allowing them to give birth more safely and comfortably in their own homes. Aside from the Royal patronage (purse!) and donations, one of the ways in which revenue was obtained to support the service was to accept Probationary Nurses from training institutions (such as the LTH’s internal Nursing School that Sylvia attended) who under the guidance of an accredited nurse/midwife (and a small fee), could gain valuable real-time midwifery training and experience by attending to women the RMC was supporting, either at home or at a Lying-in Hospital.

Mrs Lamond had originally volunteered as one of the RMC’s ‘Visiting Ladies’ whose job it was to visit mothers-to-be and post natal mothers for ‘the purpose of lending material and medical assistance, in cases of great necessity and destitution’. The ladies visited such cases in either a Homes of Service, at a Lying-In Hospital, and sometimes in their own squalid accommodation, to hand out material relief from the Charity’s Samaritan Fund. Mrs Lamond had ceased to be a ‘Visiting Lady’ and together with Dr. (Mrs) Willey took on a much more demanding responsibility by running the Home of Service at 36 King Square.

Finsbury in the early 1900s was a very depressed area of London with high concentrations of poor and consequently a very high birth and mortality rate. Those women unable to have children delivered at home, or who were destitute and without a home, were offered Lying-in facilities provide by the RMC for no charge whatever. Homes of Service were established in Finsbury Square and King’s Squares in Central London. The Homes aside from providing Lying-in facilities until the baby was born, provided meals for “expectant and suckling mothers of the poor” at a nominal charge or in special cases, free of charge. So popular was the service, expectant mothers would travel 20–30 kilometres to the Lying-in facilities in Finsbury. One expectant mother, the wife of a “jockey” and resident near Paris, is stated to have come to Finsbury from France for this purpose!

Connection – Sylvia Brown and the Lamonds

After reading this I concluded that given Sylvia’s nursing and midwifery skills which would have been most useful when required, she had stayed with Mrs Lamond while possibly assisting her at the King Square ‘Home of Service’. King Square was also close enough to the War Office for Sylvia to respond to any instruction regarding her post sick leave employment, be it in England or France which had yet to be decided.

While my research to date confirmed a connection between Mrs Lamond and Sylvia, it still did not reveal Mrs Lamond’s actual identity because once again, there were no initials or a first name which would allow me to accurately identify Mrs Lamond and her family members by name, e.g. was the Andrew Lamond (Retired) at Great Fishall a relation, father, husband, son or no relation at all?

Mrs Lamond unmasked

I decided to take a punt and follow up on “Andrew Lamond (Retired)” to see where he led me. If I could follow Andrew Lamond’s movements pre-retirement backwards from Tonbridge to see where he and his family had lived and worked, there may be a good chance I could firstly confirm whether “Mrs Lamond” was in fact his wife (or mother?) and secondly, find out her first name from a marriage (or birth) record. This process might also provide the link that I believed had existed between Mrs Lamond and Sylvia Brown from a time before Sylvia’s nursing training started in 1905.

As it happened I got as far as the 1891 London electoral register and discovered the Lamonds living at Northumberland Park in Tottenham – Andrew, Margaret M., Isobel, and Wilhelmina Lamond. I continued to trace the family until I got back to Scotland and Cortachy, Angus where Andrew had been born in 1848. Ii was during this process I discovered a previous marriage that Andrew Lamond had to a Jean MATTHEW (1830-1913). From that union they had a son, Andrew Matthew Lamond (1867-1946). The odd thing was that all of Andrew Lamond Snr’s census listings that included his wife Margaret, only ever mentioned her as “Mrs Lamond” never once using her first name! No wonder she was tricky to locate. After more delving I found a Dundee Parish record for Andrew Lamond’s marriage to a Miss Margaret (sometimes Margot) McIntyre MORRISON, born in 1845 in Perth, Perthshire, Scotland. Unfortunately this did not take me any closer to understanding how her relationship with Sylvia Brown had eventuated, but by following Andrew B. Lamond and his business I was gaining a larger picture into which Sylvia would eventually fit.

Andrew Lamond was a mercantile clerk in Dundee and after marrying Margaret M. Morrison, they had two daughters – Isabel Taylor Lamond (1879-1914) and Wilhelmina Hay Lamond (1884-1957). As Andrew’s mercantile interests grew in the wake of significant advances in mechanisation of the many forms of manufacturing, Andrew relocated his family to the commercial hub of London. The family moved from Dundee to No.2 Plevna Villa, Northumberland Park in the suburb of Tottenham in 1889. They subsequently moved to No. 77 Northumberland Park which was retained until both had retired to Great Fishall. Andrew had bought another property at Great Fishall in which their son Andrew Jnr, a bachelor and also a businessman, lived. The property was most useful as family holiday home, as well as place to stay for Margaret and Wilhelmina whenever they were away from London. It was also the place where Sylvia had been welcomed to stay as she wished.

The Lamond and Brearley connection

Andrew Lamond Snr’s commercial and business acumen made him a very successful and wealthy manufacturer and exporter of jute and its associated products. As such, he would have routinely been in contact with many other textile and cloth manufacturers in London business circles, and in textile manufacturing hub of Yorkshire. Undoubtedly this would have bought him into contact with one of the largest and wealthiest manufacturer of ‘shoddy’ in Yorkshire – Thomas Brearley, and later his successor sons Robert and Arthur, as well as the wider family on social occasions, at Great Fishall and Batley. The Lamond’s and Brearleys had much in common. Both families had their roots in Scotland, both family heads were highly successful and self made men in the textile industry, both were manufacturers and exporters all over Britain, or Europe and the Americas.

The influence of the Queen Street Mill manager Robert Brearley’s widowed mother Hannah, the surviving matriarch of the Brearley manufacturing empire, may have also played a significant part in bringing the two families into together with Margaret Lamond and Hannah Brearley becoming acquainted through their husbands. Opportunities to grow the friendship between the families would have resulted from accompanied business trips, attendances at social events, their involvement in philanthropic activities, the women’s engagement in charity work and women’s groups, and of course both family’s bond with their faith and the church – the Lamonds and Brearleys were staunchly fundamentalist Methodists.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In due course Andrew Lamond Snr retired and moved into the Great Fishall house. Margaret meanwhile continued to commute to the apartment she had retained in London from which to conduct her charity work, for as long as she was able. Andrew Lamond Snr died at Tonbridge in July 1925 aged 77, and his wife Margaret, at Hampstead just three months later in October 1925 – she was 84.

Andrew and Margaret Lamond had left their entire estate of £111,432.00 (today’s equivalent approx NZ$ 11,666,000.00) to their widowed youngest daughter Wilhelmina Hay Abbott (George Abbott died in 1947) and to her widower brother-in-law Edward Alfred GIMINGHAM, and three daughters. Edward was an electrical engineer and had married Wilhelmina’s older sister Isobel Taylor Lamond in 1906; Isobel died unexpectedly in 1914. Edward was at the time the Factory Manager for an electric lamp manufacturer. Andrew Lamond Jnr who had been the Managing Director of American Colonial Products importing agency, died in 1947 aged 79.

As I continued researching the Lamond family, I could see there were instances long before Great Fishall that would have led to a connection between Mrs Lamond, Wilhelmina and Sylvia. The biggest hint came from Wikipedia!

Wilhelmina Hay LAMOND

While looking into Wilhelmina’s background I discovered she had a biographical profile on Wikipedia. Born in Dundee, Scotland in May 1884 (five and a half months after Sylvia) Wilhelmina Lamond had been educated initially at the City of London School for Girls … and then Brussels! This was too coincidental not to be true as there was only the one prestigious international boarding school for girls in Brussels, albeit an Ursuline Convent School, and that was at Tildonk, the same school Sylvia attended! When I read this it was clear this was the common denominator between the Lamond and Brearley families.

Wilhelmina had initially attended the City of London School for Girls and was subsequently enrolled to attend the Tildonk Convent School in Brussels. With Wilhelmina and Sylvia both being of similar age, there was every reason to believe their attendances at Tildonk very possibly were either at the same time, or at least overlapped.

Students at Tildonk Convent School generally started at the age of seven and traditionally remained for approximately seven years, whilst taking an annual holiday at Christmas time back at home in England. Given the possibilities of a relationship between the Lamond and Brearleys to this point, it was small stretch to assume both girls if not previously known to each other before they arrived at Tildonk, would most certainly have made the acquaintance of every other English girl of a similar age during the seven or so years they were in residence. That being the case, I could then imagine Sylvia leaving Boston Spa anywhere between 1890 and 1894, and Wilhelmina from London possibly between 1891-1894.

Given the knowledge I had of their enduring friendship after Sylvia had left the UK, it was not hard to see how an schoolgirl friendship while at Tildonk, and after spending Christmas holidays together back in England (as was the norm for all international students), could develop into a life-long relationship as both Tildonk alumni and virtual ‘step-sisters.’

For me this scenario had a high chance of probability. It would also explain the enduring relationship Sylvia clearly had with Mrs Lamond long before 1905 when it first became known to me. Aside from Andrew Lamond and Robert Brearley having a common interest in textile manufacturing, with Andrew having a daughter whom he intended to board at Tildonk, and Robert’s (assumed) intention for his niece Sylvia to be also boarded at Tildonk for whatever reason, both men had a shared interest in the girls education which ultimately would have the effect of uniting the families in a bond of friendship.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

RETURN to ENGLAND

Wilhelmina Lamond – her story

When both girls returned from Tildonk around 1899-1900, it is assumed Sylvia went directly to The College back in Boston Spa, and if a tutor, would have been required to board at St John’s with the Sisters of Charity.

Wilhelmina’s father Andrew Lamond on the other hand, had pre-planned his daughter’s educational path. He was intent on her entering the mercantile world as a company secretary and accountant and so sent her to London in 1903 to undertake studies and gain experience in both subjects.

Suffragist and Feminist