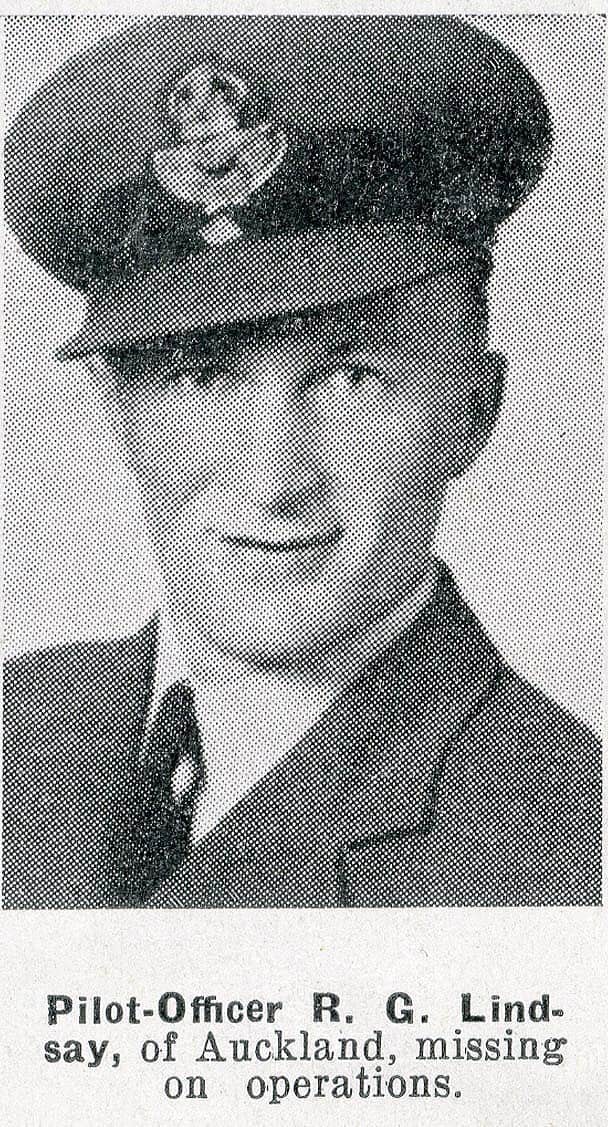

NZ 401396 ~ ROYAL GEORGE LINDSAY ~ RNZAF / RAF

An email received from Sharon H. of Collingwood Ontario, Canada resulted from a 2017 referral by the Webmaster of Aircrew Remembered.com (UK) with whom I regularly correspond as both a researcher of Kiwi airmen and for assistance with tracing UK families to reunite medals with.

Sharon’s email was the start of a fascinating but sad story that had its roots in the betrothal of a Kiwi airman to a Canadian lady. In 2006, Mrs Jean Brown FITZPATRICK passed away at the grand age of 95 years. Among her personal effects was a small cardboard box containing four items – a Pilot’s Badge (wings), a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF ) non-commissioned airman’s brass hat badge, and two paua shell (abalone) brooches – a Winged Heart and a Tiki suspended from a silver brooch pin bar. These are known as “sweetheart brooches.” Sharon explained that in 1941 her mother then Jean Brown CARTWRIGHT, had met an Kiwi aircrew cadet named Royal George LINDSAY who came from Auckland, while he was undergoing his pilot training in Ontario, Canada. Within a short space of time Roy, as he was known, and Jean became engaged to be married. After successfully completing his training in Canada, Roy was posted to Bomber Command in England. No-one then or now, is under any illusion that life during wartime can be a tenuous existence, and not least for the ‘boys in blue’ during the Second World War air war. Needless to say the inevitable happened and Royal Lindsay was killed on air operations (KAO) just months after he and Jean had met.

Broken-hearted, Jean was understandably bereft and since that time had treasured the small mementos from fiancée Roy for the remainder of her life. Sharon, herself married, fully understood the depth of feeling her mother must have had for her Kiwi flyer. Following her mother’s death, Sharon had found the keepsakes Roy had given to her mother among her personal possessions and resolved to one day have them returned to Roy Lindsay’s family. She felt they rightly belonged with the Lindsays where they would likely have significantly more meaning than if she had retained them, and no doubt be greatly appreciated after so many years had passed.

I found Sharon’s story very compelling and a welcome change of research direction and so started to assemble Roy Lindsay’s family history.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The story begins …

Samuel George LINDSAY was born in the Thames-Coromandel area in 1882 to parents George LINDSAY, a Mine Manager, and his mother Emily Ann Brown STRONGMAN. The second eldest child of five and only boy, George Jnr. took up farm work after his rudimentary schooling. By 1900 he had gone to Auckland working as a farm-hand in the Otahuhu area. He had also become a fairly capable horseman and learned the fundamentals of training work horses. In 1905 he was training horses at St Helliers Bay during which time George Annie BELCHER (1889-1918), the seventh of nine children, seven girls and two boys, born to Australian immigrant father from Sydney, Thomas BELCHER (1859-1903) and his Portsmouth, UK wife, Rachael Catherine HARDINGE (1859-1940).

“Royal George”

George Lindsay (29) did not waste much time before proposing marriage to 19 year old Annie Belcher. The pair married in 1911 and took up residence at 18 Princes Street ** in Avondale. On the 6th of January 1912, Annie gave birth to their one and only child, a son whom she and George named Royal George Lindsay. The reason for naming their son “Royal” has been long since lost in the mists of time but logic suggests a few possibilities. Could it have been because the Lindsay’s lived in “Princes Street” or that Royal Lindsay had been conceived during the coronation year of King George V – 1911.

The “Royal George” Hotel at 149 Broadway in Newmarket could also have been the motivator for their son Royal’s name. George Lindsay would no doubt have been introduced to many in the equine industry at the “Royal” from the time he arrived in Auckland and sought to establish himself as a horse trainer. The “Royal” was also very conveniently situated midway between the Avondale and Ellerslie racing courses and accordingly was a long standing and very popular ‘watering hole’ among those of the horse racing fraternity, particularly after race meetings, from the time it had opened in 1880.

Note: ** Princes Street is now part of the Auckland CBD with No.18 in the vicinity of the MacLaurin Chapel (No.12).

Tragedy in the family

George and Annie Lindsay were happy in their Princes Street home with their new son Royal, as it was close to both Annie’s widowed mother in Victoria Road, Avondale and George Jnr’s parents George Snr and Emily Lindsay who had moved to Wharf Road in Avondale (now Ponsonby) from the Coromandel after George retired from mine management before WW1.

In 1918 a Spanish Influenza pandemic swept the world and was responsible for the deaths of thousands of soldiers at war. New Zealand did not escape this scourge which struck between October and December 1918 and with the death of over 9000 citizens and soldiers. The flu also claimed six year old Roy Lindsay’s mother, Annie Lindsay on 16 Nov 1918. Twenty nine year old Annie was buried in St Ninians Presbyterian Church yard which ironically is located on the south-eastern side of the Avondale race course.

George’s sisters in the Coromandel took care of Roy until George had re-married in 1922. Ada Eunice Letitia GOW (nee Nichols) was a divorcee whose short-lived marriage in 1912 to railway engine driver George Drummond GOW, ended abruptly after the birth of a daughter, Jean Eunice GOW, in 1914. No additional children resulted from George and Ada’s union.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Royal “Roy” Lindsay was educated at Mount Albert Grammar School after which he returned to his Lindsay aunts in Coromandel and with whom he got work. Roy’s his first job was as a Cheesemaker at Turua in the Coromandel Valley. By 1936 Roy had become a grocer and moved to Puriri, a bush bound whistle stop on the north-south stock route to Thames via Kopu, now known as State Highway 26. Kopu sits squarely inside the Coromandel Forest Park and astride State Highway 26 with Puriri about midway between Paeroa and Kopu at the southern end of the Firth of Thames. Roy remained at Puriri until his enlistment application for the RNZAF was approved and he was subsequently called-up for war service in 1941. Roy’s ambition was to fly!

World War 2 – BCATP, Canada

NZ 401936 Air Cadet Royal George Lindsay was enlisted into the RNZAF as an Airman Pilot Under Training (AP u/t) on 04 June 1940. At the outbreak of war in Europe, an inter-governmental arrangement between Allied nations known as the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) or “The Plan” (also known by the name Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS)) was implemented to train large numbers of operational aircrew for the RAF’s fighter, Bomber and Coastal Command squadrons, as quickly as possible. Canada was chosen as the primary location for The Plan because of its ideal weather, wide open spaces suitable for flight and navigation training — sometimes on a large scale, ample supplies of fuel, industrial facilities for the production of trainer aircraft, parts and supplies, and the lack of any threat from either the Luftwaffe or Japanese fighter aircraft.

From 27 May 1940 the Royal Air Force introduced a minimum rank of Sergeant (SGT) for all aircrew instantly promoting all aircrew holding lower rank to Sergeant. As the war progressed Pilots (P) and Air Observers (AO) – later re-named Navigators [N] and Bomb Aimers [B] (referred to as Bombers) – were considerably more likely to be commissioned officers before the end of their operational tours as their roles were more technically demanding. Keeping pace with the enormous rate of losses, men could be promoted three times in a year. Flight Engineers (E), Bomb Aimers – ka Bombers (B), Air Gunners (AG) and Wireless Operator/Air Gunners (WAG) were more likely to be a Sergeant or Flight Sergeant (F/S) at the end of their tours with occasional promotions to Warrant Officer (W/O) rank and a good proportion as commissioned officers.

The BCATP remains as one of the single largest aviation training programs in history and was responsible for training nearly half of all aircrew who served with the RAF and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. Trainees came from the United Kingdom (RAF & RAF Volunteer Reserve), Canada (RCAF), New Zealand (RNZAF), Australia (RAAF), Poland (PAF – PSP) and Czechoslovakia (CL & CVL). At The Plan’s highest point in late 1943, an organisation of over 100,000 administrative personnel operated 107 training schools and 184 other supporting units at 231 locations across Canada. Canada alone trained 131,500 aircrew under this scheme, almost half of the projected numbers or aircrew required.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Aircrew training begins…

On 5 December 1940, Roy sailed for Canada from Wellington. On arrival at Montreal, he then travelled by train to Toronto to undergo initial training at No.1 Manning Depot, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), with effect from 23 December 1940. The Depot occupied the Coliseum Building on the grounds of the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE)** which could accommodate up to 5,000 personnel. Don’t be fooled by the pictures or grandiose buildings – the trainee accommodation was out back in cow barns and horse stables. The visible buildings were administrative offices and mess (dining) facilities.

All aircrew trainees began their military careers at a Manning Depot of which there were seven across Canada. Here trainees learned to bathe, shave, shine boots, polish buttons, maintain their uniforms, and otherwise behave in the required manner. There were two hours of physical education every day and instruction in marching, rifle drill, foot drill, saluting, and other routines. After four or five weeks, a selection committee decided whether the trainee would be placed in the aircrew or ground-crew stream. Aircrew “Wireless Operator / Air Gunner” candidates went directly to a Wireless School. “Air Observer” and “Pilot” aircrew candidates went to an Initial Training School.

Trainees were often assigned “tarmac duty” to keep busy. Some were sent to factories to count nuts and bolts, some were sent to flying schools and other RCAF facilities to guard things, clean things, paint things, and polish things. Tarmac duty could last several months or more.

Initial Training School

Pilot and Air Observer candidates began their 26- or 28-week training program with four weeks at an Initial Training School (ITS). They studied theoretical subjects and were subjected to a variety of tests. Theoretical studies included navigation, theory of flight, meteorology, duties of an officer, air force administration, algebra, and trigonometry. Tests included an interview with a psychiatrist, the 4 hour long M2 physical examination, a session in a decompression chamber, and a “test flight” in a Link Trainer as well as academics. At the end of the course the postings were announced. Those not assessed as suited to pilot training often had issues associated with night blindness, co-ordination, or distance perception. Occasionally candidates were re-routed to the Wireless (Operator) Air Gunner (WAG) stream at the end of ITS. Roy Lindsay’s aptitude streamed him toward Air Observer and accordingly he was posted to No.3 Air Observer School.

In June 1940, part of Crumlin Airport near the City of London, Ontario (about 200 km SW of Toronto) had been leased to the government by the airport authority to establish RCAF Station Crumlin. Started in 1939, Crumlin Airport was still under construction at this time however had completed two of its four runways which it leased to the RCAF for an aircrew training facility. From this time Crumlin would be host to No.1 Elementary Flying Training School (1.EFTS – Pilot training) and No.3 Air Observer School (3.AOS – Air Observer [navigator] and Bomber training) for the duration of the war.

Note: ** The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) is an annual event that takes place at Exhibition Place in Toronto during the 18 days leading up to and including Canadian Labour Day, the first Monday in September. With approximately 1.5 million visitors each year, the CNE is Canada’s largest annual fair and the sixth largest in North America. The first Canadian National Exhibition took place in 1879, largely to promote agriculture and technology in Canada, and with the exception of the First and Second World War years, has taken place continuously to the present day.

During the Second World War the 192 acre CNE grounds became home to detachments of the Canadian military. In 1939, the Royal Canadian Air Force moved into the Coliseum. The Canadian Army took over the Horse Palace and the Royal Canadian Navy converted the Automotive Building into HMCS York. During the summers of 1940 and 1941, most of the troops stationed at the CNE were re-located to permit the fairs to be held. Those troops remaining either continued their regular administrative duties or participated in CNE displays and events aimed at promoting the Canadian war effort. In 1942 the CNE was handed over to the Canadian military and the CNE ceased until after the war. During the military occupation of the grounds, virtually every CNE building, large or small, was put to use by the Canadian armed forces. The CNE grounds remained closed and under the control of the Canadian military until 1946. Between 1945 and 1946, Exhibition Park acted as a demobilization centre for returning soldiers.

Source: Wikipedia

No. 3 Air Observer School

The path for Roy’s training was 8 weeks at an Air Observer School (AOS), 1 month at a Bombing & Gunnery School (BGS), and finally 1 month at an Air Navigation School (ANS). The Air Observer schools were operated by civilians (civil airlines such as Canadian Pacific Airlines) under contract to the RCAF, however the instructors were RCAF. The basic navigation techniques throughout the war years were dead reckoning and visual flight skills, and the tools were the aeronautical chart, magnetic compass, watch, trip log, pencil, Douglas protractor, and Dalton Navigational Computer.

Roy Lindsay’s 8-week module on No.14 Air Observer Course which ran from 27 Dec 1940 to 22 Feb 1941, taught him the fundamentals of air navigation theory and included 19 flights of practical flying training in the Avro Anson (35 hours of day, and 20 hours of night flying). Roy also celebrated his 29th birthday during his course, on 6 Jan 1941.

Note: ** RCAF Station Crumlin was re-named after the war to RCAF Station London until the RCAF abandoned its use in 1961. Today Crumlin is London International Airport, the international point of entry for the province of Ontario.

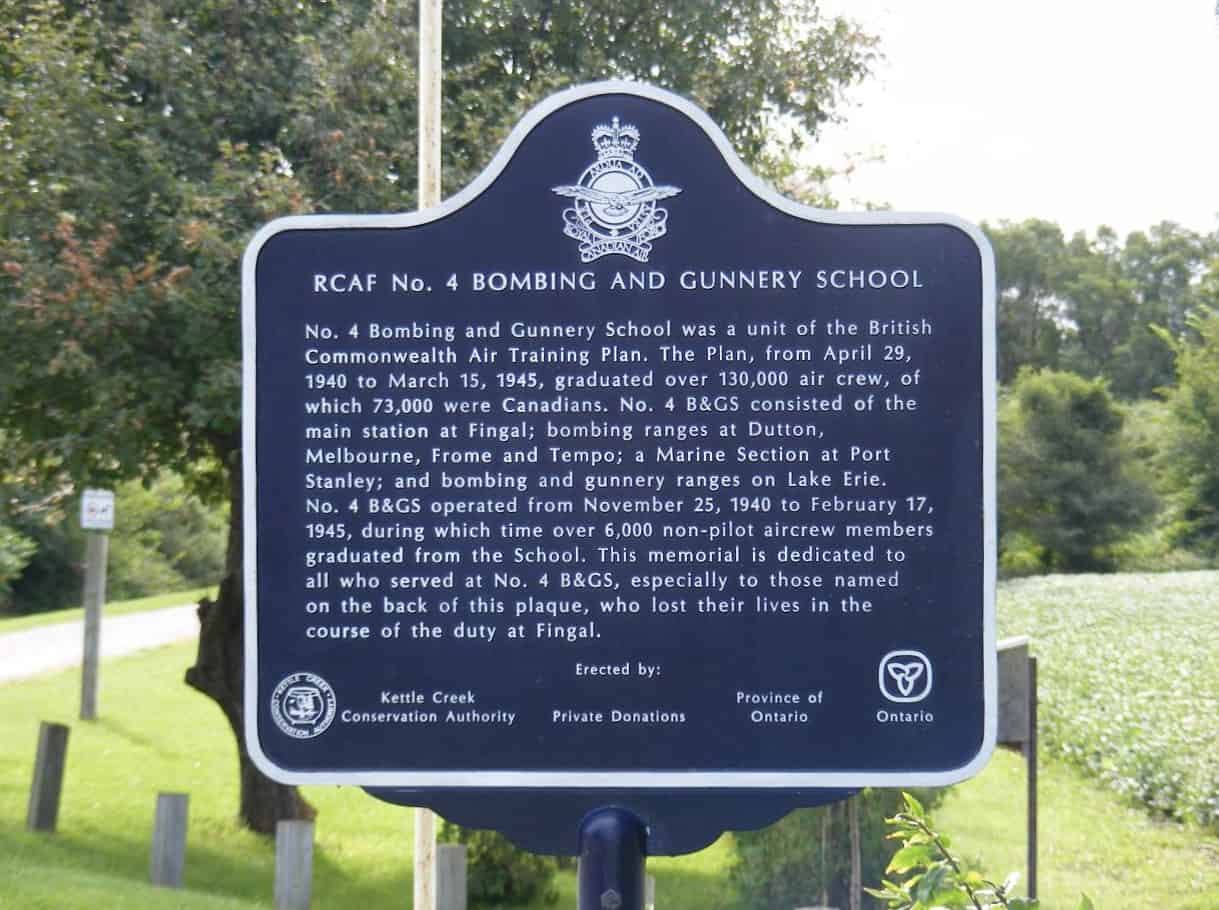

No.4 Bombing & Gunnery School

Five days of leave followed completion of the AO course and then it was off to No.4 Bombing & Gunnery School (No.4 BGS) at RCAF Station Fingal, Ontario, to complete the Air Bombers phase. Fingal is about 20 km south of the City of London. No.4 BGS trained both Air Observers and Air Bombers in their inter-related roles using a variety of aircraft that included the Fairey Battle, Northrop Nomad, Westland Lysander, Bristol Bolingbroke and Avro Anson. Air bombing ranges were located near Melbourne, Frome, Tempo, and Dutton, plus one that was located afloat on Lake Erie.

Roy attended No.11 Sergeants Air Observers & Air Bombers Course, a four week module from 18 March to 12 April 1941. Training was seven days a week, including studying and flying in the evenings, with little spare time! The weather at that time of year was also extremely cold and not unknown to hover around 40 degrees below zero!

The Gunnery phase of Roy’s course was flown in the Avro Anson and consisted of 16 flights of 30-40 minutes each, totalling about 5.50 hours. The Bombing phase of the course involved 16 day flights, a total of 29 hours, and two night flights of 2.0 hours each.

To encourage bombing accuracy, then enticement to become members of the exclusive ‘Pickle Barrel Club’ was on offer.

“Wings” Parade

After 12 weeks of intensive training and having passed all his theory a flying tests, Roy Lindsay was considered fit to graduate as a “half-winger.” A “Wings” Presentation Parade was held on 26 April 1941. The School’s Commanding Officer, Wing Commander Van Vliet, introduced Brigadier General D. E. MacDonald who gave a short talk and presented the Air Observer Badge (brevet) to 33 members of No. 16 Air Observer Course, and to the Air Gunner Course members he presented the Air Gunners Badge.

The graduands were also promoted to Sergeant AO or AG the same day. Wings parades were a popular event as family and friends were welcome to share the proud moment. It was a significant milestone for the aircrew trainees, the training was not easy by any means and the pressure remained on. The danger of what they were undertaking was never far from their minds as they reflected on those who did not graduate – the not infrequent air accidents which occurred during training took the lives of many students and staff instructors alike.

Air Navigation School

The inevitable’ graduation parties that accompanied the end of any training were generally held in week prior to the ‘Wings” presentations, as the tightly synchronised training schedules required graduated crewmen to be on their way to their next post or training school the day after a the parade. For Roy Lindsay and his fellow AOs, their training was not yet quite complete. They were required to complete one more four week module of astro-navigation before being qualified to fly operationally with a bomber squadron. No.1 Air Navigation School (ANS) was located at a place called Rivers near Winnipeg in the neighbouring province of Manitoba. Sgt. (AO) Roy Lindsay and his fellow AOs successfully completed the four weeks of training on 27 May 1941 and were commissioned in the rank of Pilot Officer the same day.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

With this ring …

With his training completed, now Pilot Officer (AO) Roy Lindsay arrived back where he started – at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto on 27 May 1941, the place aircrew posted to squadrons in the the UK stayed whilst preparing for departure and awaiting their transport. Roy was due to depart for RAF Station Driffield on 18 June 1941 which gave him just 22 days in Toronto. This was now ‘down time’ in which to relax, shop, visit some of the local sights and surrounding areas like London, Hamilton, Toronto, Niagara Falls, New York, Detroit etc and of course as young men who were about to put their life on the line did, consume great quantities of alcohol. This was understandable since their next stop would be an operational squadron in England which would be when the real work of war started … and their ‘survival’ clock begin to tick!

Sometime between Roy’s arrival at RCAF Station Crumlin, London on 27 Dec 1940, his departure for Rivers, Manitoba on 26 April 1941, and/or arrival and subsequent departure from No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto, Roy had managed to win the heart of a local lady named Jean Brown CARTWRIGHT (1911-2007). Jean was the eldest of three girls born to parents Charles Victor CARTWRIGHT, a storekeeper, and his wife Lillian May BROWN. Jean had been born in the municipality of Meaford in Grey County which is some 200 km northeast of London, Ontario on the banks of SW Georgian Bay, Lake Huron. The family in due course relocated to 39 Merritt Street East, Welland in the London suburbs. Here Jean had spent the latter part of her childhood and was schooled before starting work in her late teens in the City of London.

The actual circumstances of Jean and Roy’s meeting regrettably were lost when Jean died in 2007. Irrespective, it was clear from Roy’s concentrated training timeline that there was limited time to develop their relationship, but manage it they did. Perhaps Jean had met whilst Roy was undergoing his initial air observer training at Crumlin the previous January – February? Crumlin was certainly close enough to the city of London for a chance meeting to have occurred. Perhaps Jean had attended a social occasion at RCAF Crumlin, or been introduced via a friend of hers or Roy’s – the “Wings” presentation parades were always popular occasions at Crumlin and well attended by both local residents and those who came to see sons or relatives graduate from their training. There is also the possibility their first meeting may have happened much later – after Roy’s arrival at No. 1 Manning Depot en-route to the UK? This would have meant an exceptionally short time frame in which to form a lasting relationship.

Whatever the case, meet they did. Roy was 29 years and 4 months of age when he graduated with his Observer’s brevet, much older than the majority of his aircrew course members who were aged between 19 and 25, the norm among aircrew trainees enlisting for war service. One thing he and Jean had in common in this respect was their ages, Jean being slightly older would celebrated her 30th birthday on May 8th 1941, an age similarity to Roy’s which could also have been the catalyst for their attraction?

Relationships develop fast in war-time since the future can be so uncertain. Emotions ran high and relationships tinged with desperation, particularly as separation became inevitable. Without knowing Roy and Jean’s precise situation, what is known is that by the time Roy had departed the City of London airport in Toronto for Bomber Command in the UK, he and Jean were engaged to be married. Roy had sealed their betrothal to each other with a beautiful, rather large solitaire diamond ring. Years later, Jean would give the reset diamond to her daughter Sharon in an elegant dress ring (pictured). Their future together was assured … provided Roy survived.

Remember me

Apart from Jean’s beautiful engagement ring Roy had also given his fiancée several small mementos to remember him by while he was in England. The brass RAF hat badge was what he wore on his Field Service cap (side-hat) while an aircrew cadet and Sergeant. Once he had been commissioned as a Pilot Officer his hat and badge changed to that of an officers. The cloth Pilot’s Badge (wings) perhaps was a memento of Roy’s intended role as a pilot before he was removed from training, or it could have been a memento from one of his lost colleagues uniforms, or simply a keepsake he acquired.

The paua (abalone) shell Tiki and winged heart brooches were examples of what were known as “sweetheart badges” designed to be mementos of remembrance for female loved ones while her man was away. The theme of the two brooches were not only representative of Roy’s service and love for Jean but also of his Kiwi origins.

With their time together likely measured only in weeks or a few months at best, newly promoted Pilot Officer (AO) Roy Lindsay finally said good-bye to Jean and Canada, as he departed for duty with Bomber Command in England on 18 June 1941.

Duty Calls – 104 SQN

A total of 126 squadrons served with Bomber Command. Of these, 32 were officially non-British units: 15 RCAF squadrons, eight RAAF squadrons, four Polish squadrons, two French squadrons, two RNZAF “New Zealand” squadrons, and one Czechoslovakian squadron.

Vickers Wellington – “Whimpy”

Affectionately nicknamed the Wimpy by RAF personnel, after the portly J. Wellington Wimpy character from the “Popeye” cartoons created by E. C. Segar in 1931, the twin-engine Wellington was a long range medium bomber used extensively for night bombing in the early years of the Second World War, one of the principal bombers used by Bomber Command. In 1936 the first Wellington Mk I rolled off the production line and underwent engine, stability and armament modifications in the ensuing years. From 1943 the Wellington was progressively replaced by a four-engine, twin tail “heavy bomber” – the Avro Lancaster.

The Wellington typically had a crew of five or six aircrew. They were: the No.1 Pilot (P) commanded the aircraft, a No.2 Pilot acted as co-pilot and an Air Gunner (AG) as required, the Air Observer (AO) was the navigator / wireless operator (WOp), a Bomb Aimer (B) / Front turret (nose) Air Gunner in the front turret of the aircraft, and a Rear turret (tail) Gunner. The Wellington’s offensive bomb load of 4,500 lb (2,000 kg), was more than one-fifth of the overall aircraft’s 21,000 lb (9,500 kg) all-up weight. The defensive armaments comprised a twin .303 (7.7 mm) Browning machine-guns in both the front and rear turrets. Later modifications of the aircraft included a retractable ventral turret, and two mid-fuselage positions that could be made ready at short notice by opening a side panel of the fuselage and installing a removable gun, one on either side of the aircraft. These generally required the sixth crew member.

Wellingtons continued to serve throughout the war in other duties, particularly as an anti-submarine aircraft. It holds the distinction of having been the only British bomber that was produced for the duration of the war, and of having been produced in a greater quantity than any other British-built bomber.

Reported “Missing” …

From the outbreak of war Bomber Command crews were given the task of flying a required number of operations, known as an “operational tour”, usually of about 30 operations (the USAAF termed these ‘missions’). Only “ops” completed with the bombs dropped—later, those bringing back a target photograph—were allowed to count towards the crew’s operational tour. On completion of an operational tour the airman (and often his complete crew as they tended to remain very tight-knit, always flying together) would be “screened” (taken off operational flying) and split up as they received their future postings which would frequently be serving at Operational Training Units or Heavy Conversion Units preparing the next groups of young bomber crews for their postings to operational squadrons. The life expectancy of bomber crews was very short, with fledgling crews often being lost during their first 12 operations. Rear/Tail Gunners were the most vulnerable — their statistical expectation of survival averaged at just two weeks or four operations!) with even experienced crews being lost right at the end of their tours.

In the four months P/O Lindsay had been with 104 (Night Bomber) Squadron, he had spent a good portion of that time preparing for night operations. Towards the end of the year he had started crewing on night bombing raids into Germany in the Vickers Wellington II. By January 1942 P/O Lindsay had flown in eight successful night bombing operations over Germany.

On the night of 15/16 January 1942, RAF Wellington Mk II W5417 – EP was airborne from RAF Driffield at 1848 hours and headed for the target city of Emden to execute a raid on a very important German shipyard. The pilot in command was 19 year old Sgt. (P) Basil Adams of the RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR). His No 2 Pilot and Wireless Operator/Air Gunner was 20 year old Sgt. (P) Charles German, also a RAF Volunteer Reservist. P/O (AO) Roy Lindsay was on his 9th mission as the Observer/Navigator and at 30 years of age, the oldest member of the six man crew. The remaining crew members were RAFVR Air Gunners, Sgt. (AG) Reg Sperring (19), Sgt. (AG) Wally Tate (20) and Sgt. (AG) Reg Cooke (19). The crew had all completed a similar number of operations and roughly equivalent time in service in terms of flying experience and bombing missions. Ironically Sgt’s German and Tate had been on the same operational conversion training course (No.7) at 22 OTU as Roy had been on. Sgt. Adams had been on No. 6 Course and Sgt. Sperring on No. 9 Course.

Wellington II W5417EP never got to its target. A German flak battery situated at Ameland on the Dutch Coast shot the bomber out of the sky at 2040 hours local. Witnesses from one of the accompanying bombers saw the Wellington crash into the North Sea. No bodies or trace of W5417 – EP was ever found.

At the time he was reported missing Pilot Officer Lindsay had logged 235 flying hours and completed 8 successful missions over Europe. Roy was flying his 9th night bombing operation when his luck ran out, well before he had even reached the statistical survival average of a bomber crewman.

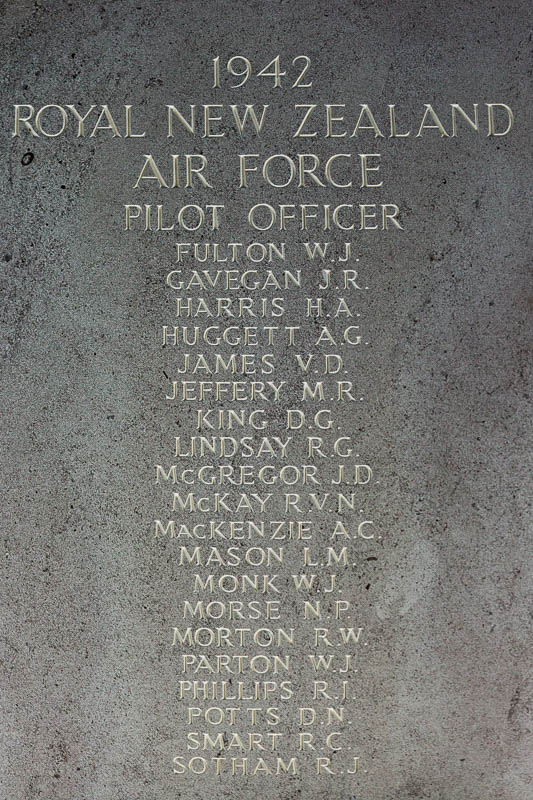

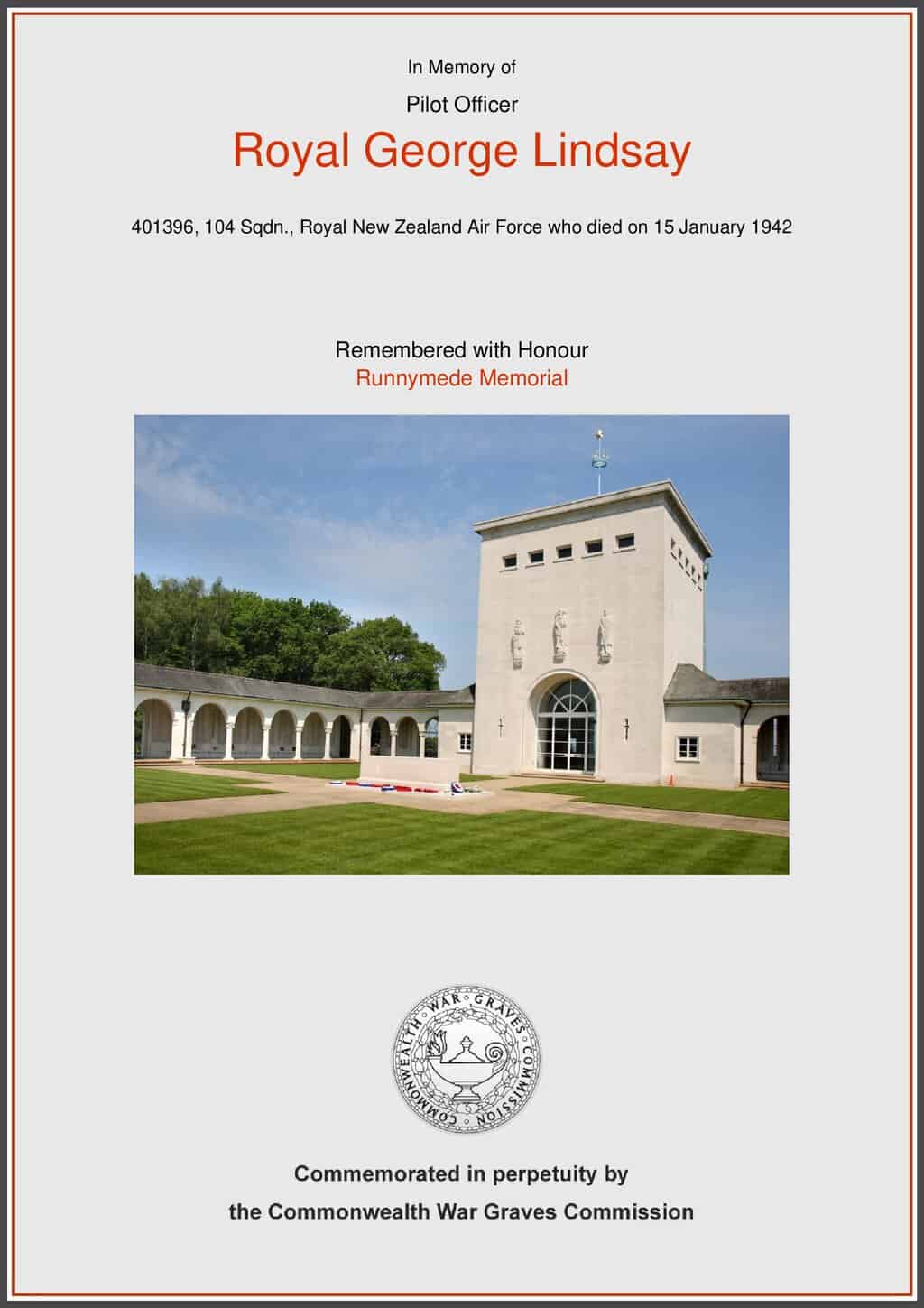

NZ 401396 Pilot Officer Royal George Lindsay (missing on ops, presumed dead/drowned) and the crew of Vickers Wellington II W5417 – EP was posted as “MISSING ON AIR OPERATIONS” the following day. With no bodies or trace of the aircraft ever found, the crew’s official “missing” status stood for many months until such time as the judiciary could legally declare them dead. The crew’s deaths are commemorated on the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial (Panel 116) at Coopers Hill, Surrey in England.

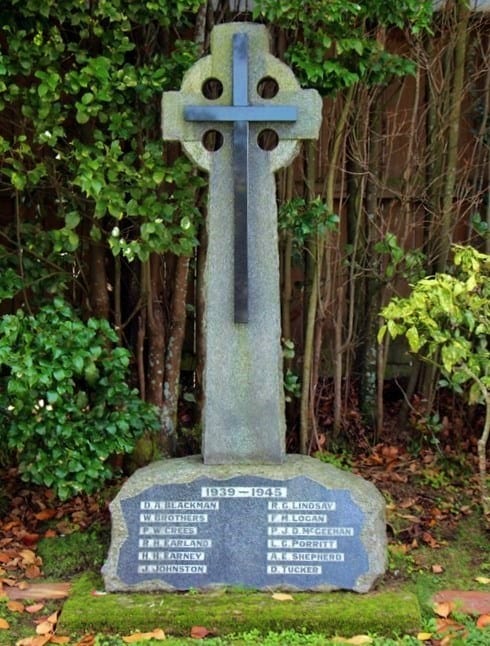

In New Zealand, Roy G. Lindsay is commemorated on the serviceman’s Memorial Cross in the historic St. Judes Churchyard, now known as the George Maxwell Memorial Cemetery, on the corner of Rosebank Road and Orchard Street, Avondale. Roy is also remembered on a memorial plaque at his former school, Mount Albert Grammar.

RNZAF in New Zealand: 184 days

Service Overseas: 1 year 41 days

Total RNZAF / RAF service: 1 year 225 days

The BOMBER COMMAND clasp for the 1939/45 Star was instituted on 26 February 2013 to acknowledge the contribution and sacrifice of those who served in Bomber Command during WW2. Thr only other Clasp worn on this ribbon is BATTLE OF BRITAIN.

Jean joins the RCAF

W313807 Corporal Jean Brown Cartwright (1911-2006) RCAF-WD

After an extended period of mourning Jean was encouraged to act upon a recent law change which permitted Canadian women volunteers to enlist in the armed forces to fill non-combat positions, only within Canada. Following the outbreak of war in Oct 1939 there was a nationwide outcry by women who at that time were denied any opportunity to serve their country by joining the military services. The United Kingdom had permitted their women to enlist from the outset, being seen as necessary to free up the considerable numbers of males required for all three armed services. This also had the effect of depleting the industrial and domestic infrastructure of the country. As the war continued and casualty numbers soared, the employment of women in the non-combat rolls within the uniformed services, became an absolute necessity for both the continuity of domestic operations as well as the support required for operations overseas.

By the time Jean volunteered her services in June 1943, the organisation had been re-named the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) – Women’s Division (RCAF-WD) and the women known as “WDs”. Being older and more mature than the average female entrant, Airwoman (AW) Jean Cartwright was identified for administrative duties and as a supervisor of female trainees entering the service.

Cpl. Jean B. Cartwright was honourably discharged on 31 July 1946. For her service she was awarded the following:

Awards: Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and War Medal 1939/45; War Service Badge – RCAF Reserve

War Service: 02 June 1943 – 31 July 1946

In June 1947, Jean married former Canadian soldier and Veteran of the First and Second World Wars, Captain Willson Duncan FITZPATRICK. During WW1 Duncan had served as a Gunner with the 31st Battery, Canadian Field Artillery and later as a Sergeant with the 1st Battalion, 164th Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) during the First Battle of the Somme in France. In 1917 Duncan sought to join the Royal Flying Corps however after five months of training he was mobilised for overseas service, and placed with the 14th Signallers Section, Canadian Engineers. It was whilst with the Signallers he was wounded, suffering the effects of an artillery barrage of gas shells which necessitated his evacuation to England. Following his recovery, Duncan returned to Hamilton Ontario and continued to serve on a part-time basis with the local militia unit based at Hamilton – the Canadian Fusiliers [City of London Regiment] (Machine Gun).

The C.F (CoLdn) (MG) unit was mobilised at the outbreak of WW2 in 1939 and tasked with providing the defensive firepower for the Headquarters of the 6th Canadian Army Division. Duncan was re-enlisted for full-time service and commissioned in the rank of Lieutenant.

Kiska in the Rats Island group of the Alaskan Aluetian Islands, is situated in the middle of the Bering Sea to the west of Alaska. To conclude the Aleutian Islands campaign, an Allied task force operation known as Operation COTTAGE to clear and occupy Kiska Island which had been occupied by Japanese forces since June 1942. On 15 Aug 1943 the Allied task force which included 6.CanDiv, launched an attack on Kiska which very quickly became a non-aggressive occupation as the Japanese had departed undetected.

Capt. Duncan Fitzpatrick was demobilised in September 1945 as Captain and Quartermaster of the Canadian Fusiliers (CoLdn) Regiment. Following his marriage to Jean in 1947, Duncan and Jean lived in Hamilton and had a daughter, Sharon, the lady responsible for this journey of discovery to find her mother’s war-time fiancée’s descendant family in New Zealand.

All that remained …

Clearly Jean’s mementos of Roy were very special to her as was her beautiful engagement ring which she gave to Sharon in later life. The lamentable part of Roy and Jean’s short relationship is the complete absence of any photographs of them together – either none were taken, or survived. It is not unknown for those with a broken heart to want to expunge the hurt of losing a loved one by removing all reminders of them, such is their grief – we shall never know if this was the case with photographs but clearly Jean’s feelings for Roy had run deep and no doubt stayed with her all the days of her life, perhaps wondering at times what might have been. After all that had happened, Sharon said her mother had never spoken of Roy until very late in life.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

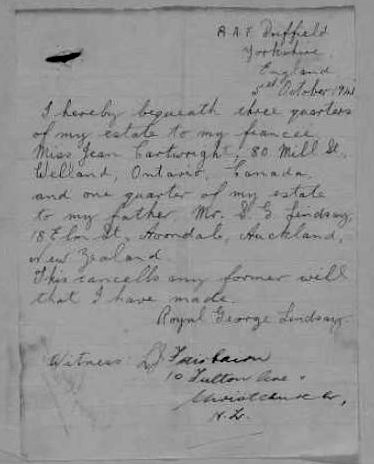

Last Will and Testament

Prior to Roy Lindsay’s departure from NZ for Canada he had drawn up a Will with Mr P.G. Finlay from the his father’s firm of Solicitors, Messuiers Wilson, Henry and McCarthy to draw up a Will. Roy’s relationship with Jean Cartwright however had prompted him to make a new Will in the event of his death. On arrival at RAF Driffield Roy had pencilled a Will dated 5 October 1941 which he signed and had witnessed by a colleague, L. J. Fairbairn of 10 Fulton Ave, Christchurch. The Will was not officially Attested by a solicitor.

Roy’s new Will had made his fiancée Jean Cartwright the beneficiary of three quarters of his Estate while the remaining quarter was willed to his father, Sam Lindsay. After his disappearance on 15 Jan 1943, Sam Lindsay had to wait for 12 months before his son’s affairs could be settled, this being the elapsed time required the court allowed before a declaration of nil contact and presumed death could be made. When Mr Finlay bought the “new Will” to light, its acceptance had to be argued in the High Court as valid under the precedence of a previous case which recognised that a missing soldier was still a “soldier in actual military service” until proven otherwise. As a consequence, a letter from the RAF several months later stated that “for official purposes, Royal George Lindsay was considered to have lost his life on 15 January 1942.”

In addition, permission also had to be sought from Jean to give Sam Lindsay permission to administer the terms of the Will. All this took time to be processed through the NZ High Court. Roy Lindsay’s Estate was finally settled in Dec-Jan 1944. His Estate had amounted to approximately £15oo.00. Jean’s share was £1125.00, the equivalent in 2019 of £49,474.50, or NZ$ 97,365.00. Sam Lindsay’s quarter share was £375 , the equivalent to £16,491.50 in 2019, or NZ$32,440.00.

The Lindsay lineage

My research into the descendants of Roy Lindsay proved particularly difficult. With Roy being an only child there was not the usual possibility of finding descendant families of siblings. I looked at possible descendants of his mother Annie Belcher’s line however this proved equally elusive. Annie Lindsay was one of eight siblings (seven girls and a boy). She had died in 1918 during the world-wide Spanish Influenza pandemic. All of Annie’s surviving siblings had been females and all had died before the age of thirty bar one – only two had had any children. Their subsequent marriages had made these families too difficult to remote in the descendant chain to be concerned with and so I resolved not to go down this route unless a more deserving descendant should appear in the mix.

Following his wife Annie’s death in 1918, Sam Lindsay re-married in 1922 to Ada Eunice Letitia GOW (nee Nichols), a divorcee whose 1912 marriage to George Drummond GOW, a railway engine driver, had ended after only a few years but not before the birth in 1914 of their only child, Jean Eunice GOW.

No additional children had resulted from Sam Lindsay and wife Ada’s union. Roy being Sam’s only child and Jean being Ada’s only child, the marriage of Sam and Ada meant that Roy and Jean became step-brother and sister to each other.

At this point in my research I resorted once more the very useful Ancestry Family Trees and their attendant authors to try and make some potential connections to the Lindsay family of Avondale. A couple of responses had me pursing a couple of alleged close connections which proved not to be. After a couple of months with no further meaningful connection to follow, the case went on the ‘back burner’ until I could devote more time to in-depth research.

In April this year (2019) I received an email from Zac Williams (Zachary Benjamin Williams, 1995) who stated he was contacting me on behalf of his grandmother, Noeline Jean MAXWELL, nee STONEX, whom he alleged was the niece of Royal George Lindsay. Zac said the family had been researching Roy Lindsay to learn more about him and in the process had come across the message I had added to Roy Lindsay’s Cenotaph profile page indicating that MRNZ was holding medals/ephemera that had belonged to Roy. Zac’s grandmother was interested in claiming the ”medals” and wanted to know what was required.

Further research showed that Noeline Maxwell had been the only child of Jean Eunice GOW and Frederick Benjamin STONEX. Noeline in turn had been married twice, first to jockey Keith William DULIEU with whom she had a family of three daughters –Deborah Kay, Sheree Dianne and Michelle Louise DULIEU. Following Keith’s death, Noeline Dulieu was re-married to Trevor Gilbert MAXWELL, a Magistrate and Court Judge. No children resulted from their union.

The youngest daughter of Noeline’s first marriage to Keith Dulieu, is Michelle Louise the wife of Cambridge truck driver Mark WILLIAMS, and parents of Zac.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‘Always Remembered’

The William’s family has had the newspaper photograph (above) of Roy Lindsay displayed in their house for many years as their own tribute to an ancestor who fought and died in WW2, a relative they never knew or knew much about until recently. I was able shed a little more light on Roy’s life and death for Zac which has now been encapsulated on a tribute page of the AircrewRemembered.com website.** Zac (24) has also been putting in some research time on Royal George Lindsay and learned that his medals and Memorial Cross commemorating his death were sent to his father Sam Lindsay at 18 Elm Street after the war.

Zac Williams has since assembled a replica set of Roy Lindsay’s medals which he will be able to wear on Anzac Day and Armistice Days in honour of his great uncle. Whilst researching Roy’s medal entitlement, Zac discovered an omission had been made from the original medal entitlement. It seems Sam Lindsay was never sent his son’s Defence Medal as part of the complete entitlement. This I confirmed with the help of Defence PAM section’s medal entitlement expert, Karley C. who has now arranged for the medal to be issued to Zac. Having one genuine medal among Zac’s set of replicas is better than having none at all.

The whereabouts today of Roy’s original medals and his Memorial Cross is unknown. Given that WW2 medals issued to NZ servicemen and women were unnamed, the chances of finding them if not with a family member somewhere is fairly remote – unless the medals are accompanied by the Memorial Cross.

Sharon H. mentioned that she remembered her mother Jean had kept up regular correspondence with Eunice Stonex for many years after the war – at Christmas, birthdays, holidays etc. There were even longer letters she recalled with an accounting of all the family’s activities. Sharon could remember the letters still coming to their house at least into her teenage years in the 1960’s and 70’s. Now sadly both ladies are deceased and that link is broken. Michelle and her family at least have Jean’s daughter Sharon as a fresh point of contact for any questions which may remain unanswered.

Note: ** The commemorative page that details P/O Lindsay’s last operation can be found here: AircrewRemembered.com/RGLindsay

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Roy’s father Sam Lindsay built up a successful racehorse training and breeding business at Avondale which made him quite wealthy during his lifetime. Sam is remembered as a trusting and generous man, perhaps too generous and too trusting, qualities that were sometimes taken advantage of by those in the bloodstock and racing industries. Sam Lindsay died at his home in Elm Street in 1952 at the comparatively young age of 62. His wife Ada remained at No. 18 for another year or so before selling and taking up residence in a small, red brick house at 1137, New North Road in Mt. Albert. Ada outlived Sam by another 25 years before she to passed away in 1977 at the age of 88.

Royal George “Roy” Lindsay’s direct line of succession effectively ended with the death of his father however his memory and exploits with 104 Squadron RAF have never been forgotten by the RNZAF or the Williams household. Apart from being remembered on the Runny Meade Memorial in England, his name also appears on the Wigram Airforce Museum’s memorial wall, and is recorded in Errol W. Martyn’s book “For Your Tomorrow: Volume Three.” Indeed, Roy’s memory has now been significantly revived and enhanced in the Williams household since the return of Jean B. (Cartwright) Fitzpatick’s personal and precious mementos of a love once had, and lost.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sharon H.’s foresight in seeking to return her mother Jean’s wartime mementos to Roy Lindsay’s descendant family has been a special gift that has opened up a world of information not previously known by the Williams family who are immensely grateful for Sharon’s gift – thank you Sharon.

Thanks to Karley C. and the PAMs staff at Trentham for again applying their expertise to clear the muddied waters of speculation which on this occasion resulted in the discovery of an entitlement to two additional awards.

The reunited medal tally is now 299.

Per Ardua Ad Astra

‘LEST WE FORGET’