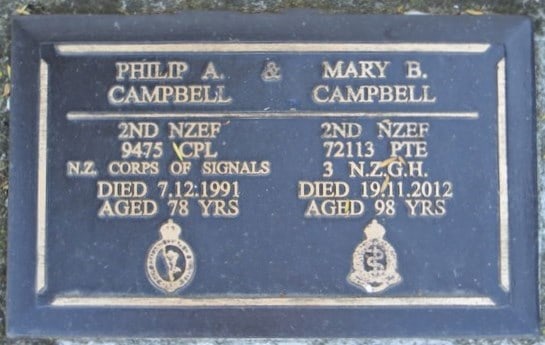

9475 ~ PHILIP ALEXANDER CAMPBELL

Born and raised in Dunedin, grocer Frank Muntz volunteered for war service in 1939 and joined the South Island nominees for the First Echelon in training at Burnham. 8541 Corporal Francis Raymond “Frank” MUNTZ was assigned to the NZ Army Ordnance Corps and departed Lyttelton aboard the HMNZT Z6 MS Sobieski, one of six troop ships including the Empress of Canada, Strathaird, Orion, Rangitata and Dunera that departed as a convoy from Wellington on 5 January 1940 with the First Echelon aboard. This was the first of the three Echelons of troops which would form the bulk of the 2nd (NZ) Division.

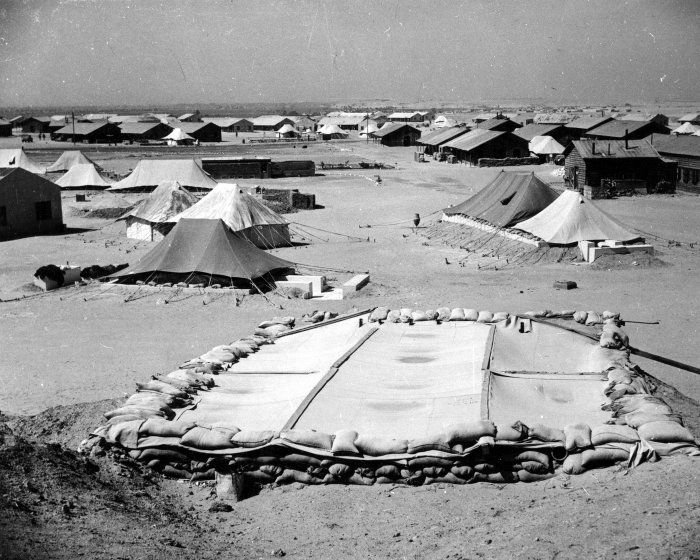

The NZ Division was initially tasked operations on two fronts – the Italian campaign and the beginning of the North African campaign. The advance of German and Italian forces had spread into Italy and they had also gained a toe-hold on the North African continent along the Mediterranean Coast including Algeria and Libya. The Germans had designs on capturing Egypt and all else before them, until they reached Cairo.

As readers of the NZ Army’s history in North Africa know well, within a matter of months in 1940 the NZ forces would be engaging the both German and Italian aggressors in fierce fighting in Syria, the Libyan desert, and at key locations such as Tobruk and El Alamein. The NZ Division would also mount operations in Greece, on the island of Crete, and Italy.

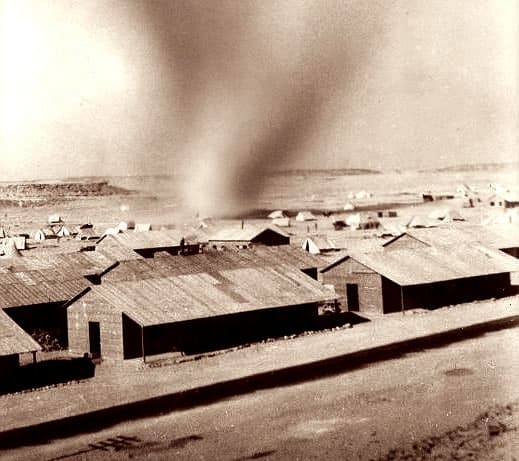

Frank Muntz like most aboard the MS Sobieski was both apprehensive and full of anticipation, however all he imagined lay before him, at that moment seemed a world away as the 1st Echelon convoy heaved its way across the Pacific. Once the troops arrived in Egypt there would be much to do in establishing the NZ Division’s base camp at Maadi, as well as training, training and more training before the soldiers would get a crack at their enemy. The ship’s passengers had little to do except write letters, some light weapons training and regular fitness sessions to keep them occupied. A holiday-like mood prevailed whenever the sailing was smooth and the weather warm and fair, often the case as ships reached Zero Degrees Latitude – the Equator.

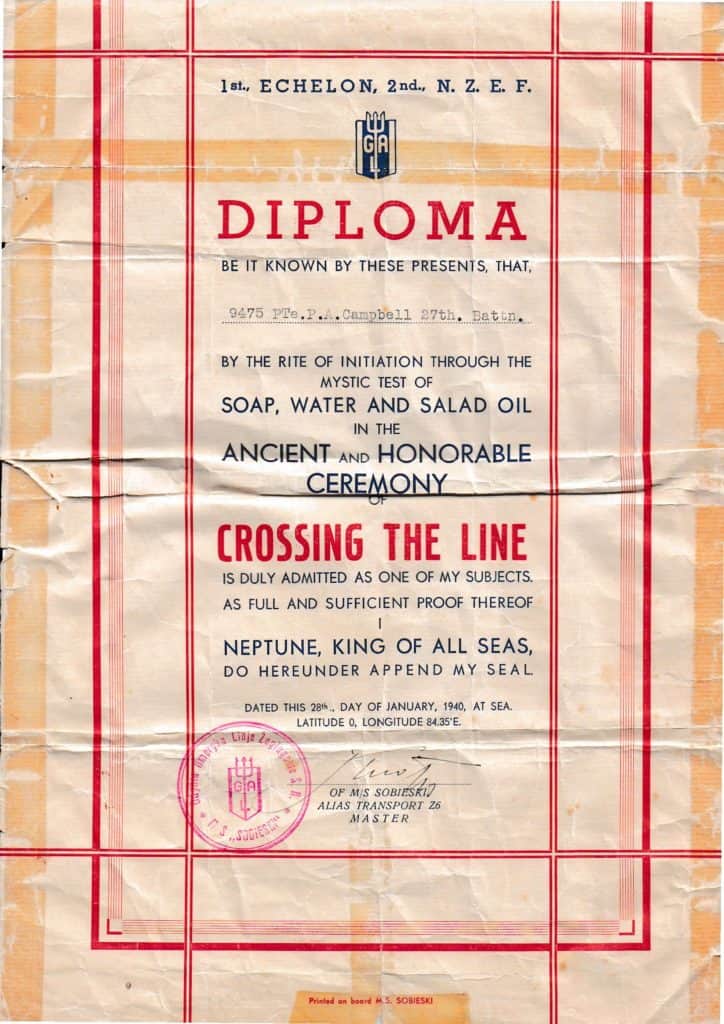

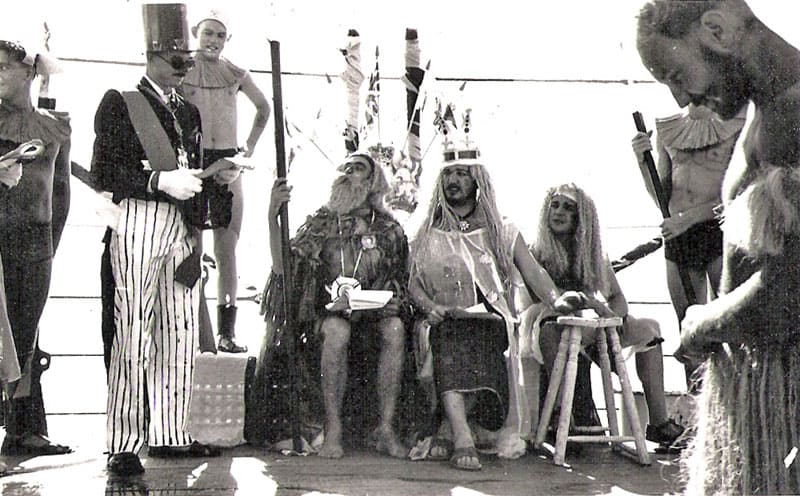

Every sailor at sea who crosses the Equator for their very first time is the subject of a special ceremony that invariably will be one of his most enduring memories of life in the Navy. The ceremony is known as “Crossing the Line” and has a special significance for those of the sea-going persuasion. Once the ceremony is over, each sailor is presented with a certificate or ‘diploma’ which commemorates their participation and bestows upon each, membership of a unique and select fraternity. Frank Muntz** became a member of this unique maritime fraternity whilst on board the MS Sobieski.

Note: ** Cpl. Frank Muntz became a POW while on Crete, one of 2,180 New Zealanders taken prisoner and the largest number of NZ POWS ever taken in a single action. Frank survived the rigours of the German POW camps for the remainder of the war and was eventually repatriated, first to England and then to NZ aboard RMS Rangitikei, arriving at Wellington on 2 September, 1945.

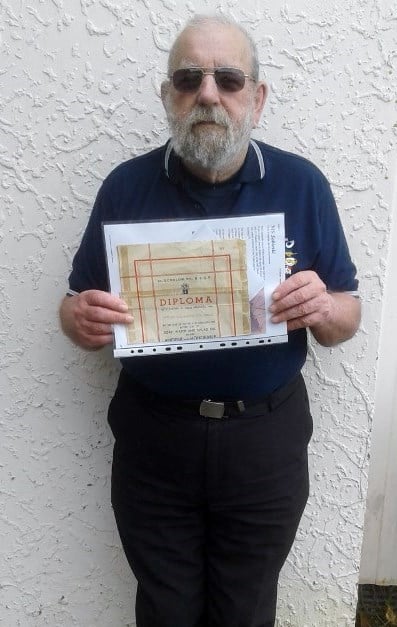

The ‘Diploma’

A former military colleague emailed me in September last saying he had found a “diploma” in his deceased father’s papers. Allan, a retired RNZAF officer, is the son of Frank Muntz and also the incumbent Vice President of the Fielding RSA. When Allan found the certificate among the papers of his deceased father (Frank passed away at Nelson, 03 Dec 1993 aged 76), he also found a second Diploma, named to 9475 Private Philip Alexander CAMPBELL – 27th NZ Machine Gun Battalion, later Corps of Signals. Allan indicated to me he would very much like to see the “diploma” returned to the family if possible? We would certainly try.

“Crossing the Line” – a brief history

The ceremony of Crossing the Line is unique and one that not only perpetuates an ancient nautical tradition that can be traced back to the French in the early sixteenth century, but is also considered a rite of passage every sailor is expected to undertake once in their maritime career – the first time they cross the Equator at sea. It is an eagerly anticipated ceremony although understandably, with a good degree of trepidation.

By the mid-sixteenth century, sailors had begun to regard it as an ancient right that they baptise those who had not been over the Equator before, and they did so by blacking themselves and dressing up in costumes. Many at that time believed that anyone of another race who crossed the equator would become an African.

By the mid-sixteenth century, sailors had begun to regard it as an ancient right that they baptise those who had not been over the Equator before, and they did so by blacking themselves and dressing up in costumes. Many at that time believed that anyone of another race who crossed the equator would become an African. The ceremony evolved into a more brutal affair in times past than practised today with sailors being whipped, thrown overboard, dragged in the sea, and suspended by the ankles or wrists in the sun whilst blindfolded.

Pollywogs and Shellbacks

Crossing the Line in earlier times was a serious business with the rituals lasting for up to a week prior to the initiation ceremony proper (Pollywog Day) taking place. The rituals started with a period of isolation, prayer and giving of thanks followed by a series of steps representing the transition from a ceremonial death to a ceremonial rebirth. The transition was comprised chiefly of two parts: a religious ceremony of thanksgiving, and an initiation ceremony that marked the transformation of inexperienced sailors, or “Pollywogs”, into trusted crew members (Shellbacks)

A similar ceremony took place during the second survey voyage of HMS Beagle . As the ship approached the equator on the evening of 16 February 1832, a pseudo-Neptune hailed the ship. Those who ran forward in response to Neptune’s call “were received with the watery honours which it is customary to bestow“. The officer on watch reported a boat ahead, and Captain Fitzroy ordered “hands up, shorten sail“. Using a speaking trumpet he questioned Neptune, who would visit them the next morning. About 0900 the next day, the novice seamen or “griffins” were assembled in the darkness and heat of the lower deck, then one at a time were blindfolded and led up on deck by “four of Neptune’s constables“, as “buckets of water were thundered all around“. The first “griffin” was Charles Darwin, who noted in his diary how he “was then placed on a plank, which could be easily tilted up into a large bath of water. They then lathered my face and mouth with pitch and paint, and scraped some of it off with a piece of roughened iron hoop. — a signal being given I was tilted head over heels into the water, where two men received me and ducked me. — at last, glad enough, I escaped. — most of the others were treated much worse, dirty mixtures being put in their mouths and rubbed on their faces. — The whole ship was a shower bath: and water was flying about in every direction: of course not one person, even the Captain, got clear of being wet through.“

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Ceremony

The line-crossing ceremony is an initiation rite that is conducted for a person’s first crossing of the Equator. It is an enduring memory of each and every sailor as it is an event that ushers in a sense of belonging to one’s crew and the seafaring profession.

Obedience and the profession of loyalty is an integral part of the ceremony. Aside from the theatrics, the ceremony also plays an important part in fostering crew camaraderie and morale.

The ceremony can also provide a welcome break for the crew during difficult and occasionally long, monotonous voyages. Arduous ship routines, rough seas or the constant threat of injury or death in times of tension or conflict, is made more endurable with the ceremony which in peacetime is considered to be entertainment. While ceremonies can vary from ship to ship, in essence they have similar components as set out in the next paragraph.

Preparation

All Pollywogs aspire to become Shellbacks. To do so they must subject themselves to a ceremony which initiates them into the “ancient mysteries of the deep.” Traditionally, the night before crossing the Equator, King Neptune sends a messenger, sometimes Davy Jones, informing the Captain that he intends to board the ship the following day, and summons a list of the uninitiated (Pollywogs) to appear before him.

‘Pollywog Day’

The day of the initiation ceremony is called “Pollywog Day”. The day is run by a group of experienced crew members (“Shellbacks” – senior ranking sailors), presided over by King Neptune and his Court Shellbacks (Sons of Neptune) including Queen Amphitrite, Triton their son (the royal baby), and Davy Jones. Davy Jones is traditionally impersonated by the smallest sailor on board, given a hump, horns and a tail, and his features made as ugly as possible. He is swinish, dressed in rags and seaweed, and shambles along in the wake of the sea king, Neptune, playing evil tricks upon his fellow sailors. All are dressed in theme for the occasion.

Pollywogs are summoned on deck and accused of various farcical misdeeds for which they will be “prepared” before achieving an audience with King Neptune in the hope of being admitted to his realm as a trustworthy Shellback. The Pollywogs are “prepared” for their audience by Neptune’s trusty Court Shellbacks.

They are first doused in fresh water – either in a temporary canvas type pool arrangement set up on deck, or are hosed down. Activities of “preparation” can involve the Barber snipping a Pollywog’s hair in a ragged and in-complete fashion, being whipped (with rolled up newspapers) while duck-walking or crawling around the deck on their knees and being taunted by surrounding crew members. Various parts of the their bodies may be daubed with (soluble) mixtures such as whitewash, sauce and flour. Pollywogs will have to drink a foul tasting concoction akin to a mixture of beer, chilli sauce and raw eggs. This is a symbolic of a ‘truth serum’ meaning they shall speak only the truth when swearing allegiance to Neptune and the Sea. “Preparation” can also involve crawling through garbage, eating coloured food, allowing the Royal Doctor to administer to them, and kissing the Royal Baby (the fattest Chief Petty Officer on board) on the belly! The Royal Navigator, Royal Scribe, Dentist, Policemen, Chaplain, Judges, Bears, and Attorneys will also have input to the “preparation” which continues throughout the day.

The penultimate ritual is a “shaving” by the Royal Barber with a huge wooden “razor,” after which one is dunked in a tub of water (often dyed a hideous colour) to “cleanse” them for the final meeting with King Neptune. The Pollywogs are then rounded up by the Police for an audience with Neptune. Davy Jones presents them before Neptune and his entire retinue, proclaiming them to be trustworthy fellow sailors. Neptune deliberates and makes a judgement as to their acceptance.

Finally, a raw egg broken is broken on the head of each Pollywog to signal their rebirth as Shellbacks, followed by a dunking/hosing in sea water to signifying their loyalty and acceptance by King Neptune, and that they are now at one with the Sea.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ancient Order of Shellbacks

The day ends with each of the newly initiated Shellbacks receiving a “Diploma” that commemorates the Crossing the Line ceremony and announces their initiation into the Ancient Order of Shellbacks (or Ancient Order of the Deep) thus earning a safe passage at sea. The new Shellbacks have the privilege (revenge!) of being King Neptune’s Court Shellbacks and “administer” to the next group of Pollywogs to be initiated when the ship Crosses the Line again.

Equator-crossing ceremonies, are common in navies world-wide and are also sometimes carried out for passenger entertainment on civilian liners and cruise ships. They are also performed in the merchant navy and aboard training ships.

The Royal Navy has had established Crossing the Line ritual practices since the seventeenth century which have been modified and are bound by written regulations (as are most commonwealth Navies) designed to limit the risk of injury while maintain the reputation of the navy. In some navies the Crossing the Line ceremony has been extended to ceremonies for other historically significant nautical features, e.g. Crossing the Arctic Line, Antarctic Line, International Date Line, transiting the Panama and Suez Canals, or rounding the Horn of Africa and Cape of Good Hope.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tracing Philip Alexander Campbell

To find a living descendant of Philip Campbell, my research started with his service record. As many will know there are no WW2 digital military service files connected to the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph website – there is only an incomplete set of predominantly soldier’s personal profile pages that contain minimal detail at best. Having collected Philip Campbell’s basic details I decide to try and resolve the case without spending money for a copy of his archived file.

Ancestry.com allowed me to trace Philip and his family from his birth in Arrowtown to the various locations he had lived and worked while an employee of NZ Railways, during his WW2 and post war service, through to his eventual retirement and death. Given I was starting in the location Philip and Mary had been first listed in the Otaki Electoral Roll (1972) and Philip’s place and date of death (Otaki), I focused on this geographical area for persons with the Campbell surname which I extended to include Kapiti, Levin and as far as but not into, Palmerston North.

Ancestry.com Family Trees that included Philip and Mary Campbell indicated they had had at least two children, a boy and a girl, both of whom remained nameless in accordance with Ancestry’s policy of not publishing names of the living. To get around this I estimated a year for the birth of the first child basing this upon a very unscientific formula – many children are born within the first two years of marriage (a very hit and miss method). From the year Philip and Mary Campbell were married, I added two years plus 20 years to allow for a child’s first appearance in an Electoral Roll once they turned 20 years of age. This then left me with the a time period from 1969 to 1981 in which a Campbell child might appear, 1981 being the limit of Ancestry.com records.

From these I located a listing for an RNZAF Airman, Fergus Ian Campbell, who appeared on just four occasions – 1969 Whenuapai, 1978 x 2 at Wigram and Ohakea, and 1981 Ohakea while living at Bulls. I started with Ian for no other reason than I had served at Ohakea as did Fergus, purely to see where his trail led me. I happened to be very lucky with this choice as it turned out, but also sometimes you just get a feel for a person or family that you are looking for, whether it is something about their name (the Scots connection in this case as Philip’s ancestors had originated from there), or possibly the proximity of their family after retirement. Looking at a person’s work type, marriage and movements can generate a raft of ideas and patterns that need to be tested when there is no other obvious lead.

I cross referenced the geographical areas of interest with the Campbell surnames listed in the White Pages – nothing obvious there. No luck with a random entry into Google, however by entering Fergus’s name into Facebook, it produced a positive reference to his name but not as a personal FB page, it related to a business – Fergus Campbell, Marton Mini Cabs. A call to the company informed me that Fergus had suffered a stroke and was no longer working with Marton Mini Cabs. With no listed phone number, the very kind proprietor put me in touch directly with Fergus who soon confirmed to me that his father was indeed Philip Alexander Campbell.

Whilst Otaki had a particular interest for me as I had lived and attended secondary school there, I was also very familiar with Freemans Road in which two of my class mates had lived and was also located very near the street in which I had lived. Finding Fergus had also produced yet another coincidental connection as I researched this case. Fergus and I had both served at Ohakea as airmen. While our RNZAF careers had overlapped albeit at different air bases, Fergus had finished his 20 year career as an Electrical Avionics Technician, at Ohakea in Dec 1985 whilst I had arrived to start my final four years of twenty, in 1986. I had just missed him being on the base at the same time as Fergus or we could have known each other through the appointment I held. Fergus told me he had enlisted in the RNZAF as an Electrical & Radar Technician in 1965 and during that time, had also spent three years as aircrew, a Helicopter Crewman on the Bell UH-1H Iroquois helicopters of No.3 Squadron before he returned to aircraft electronics and avionics maintenance in his ground trade.

Having also given me a number of interesting anecdotes about his father’s service in North Africa, I was more than satisfied that Fergus was the person to whom the ‘diploma’ should be returned. I contacted Allan Muntz, gave him the good news re Fergus, and arranged for Allan to deliver the document in person to Fergus, which he did promptly.

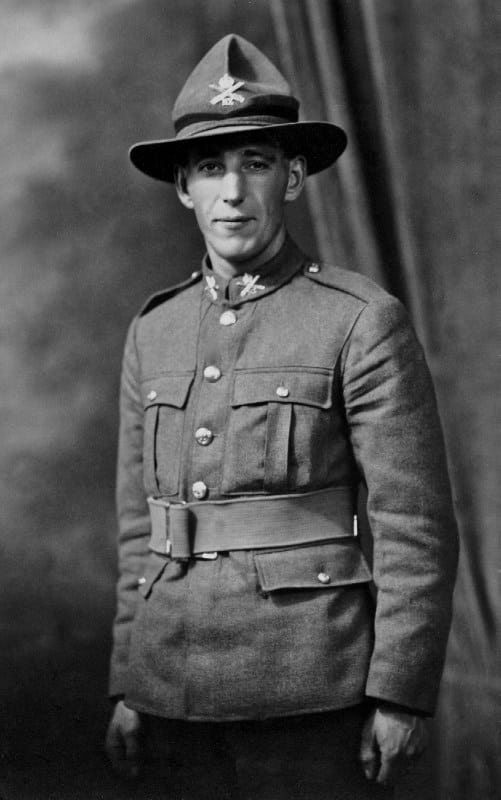

Philip Alexander Campbell

After establishing Philip Campbell’s military identity and the unit he had served with in WW2 (thanks to Cenotaph), I began to reconstruct his family tree from the on-line family records available.

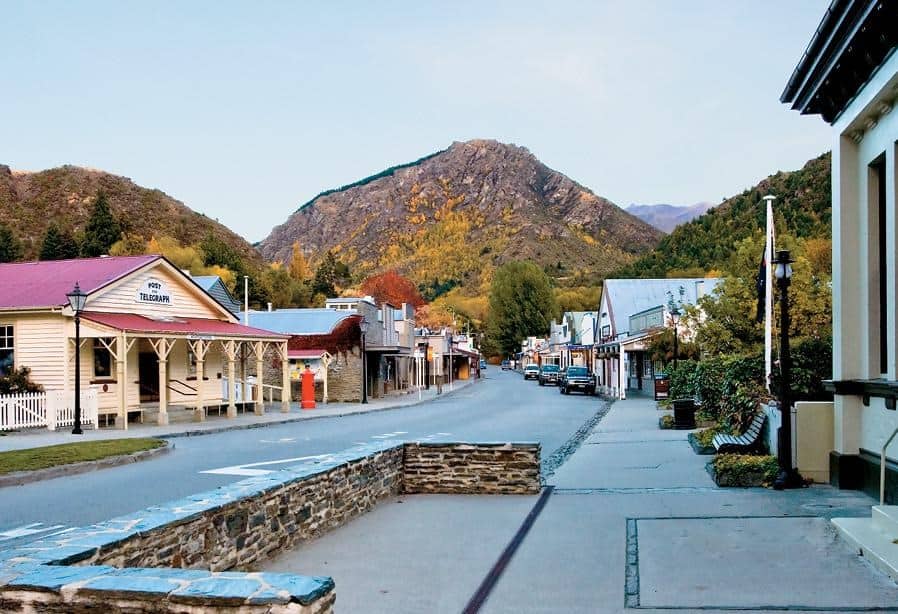

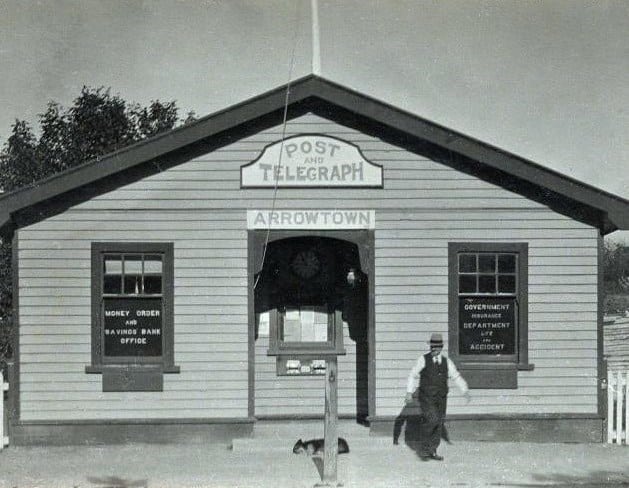

Born in February 1913 at Arrowtown, Philip Alexander Campbell was the fourth of six children (only five of survived) to father Gordon Campbell (1887-1935) who had originated from Ashburton. Gordon was a 22 year old Telegraph Cadet when he married 25 year old spinster Maud Mary WEBB (1885-1949) in the town of her birth, Arrowtown, in Feb 1908. The Campbell’s had six children, all of whom were born in Arrowtown however only five.

Philip’s siblings were, James Francis “Jim” CAMPBELL (1908-1984), Gordon CAMPBELL Jnr. (1909-1980), Maud Ellen “Moya” CARNAHAN (1911-2005), Philip Alexander “Phil” (04 Feb 1913–07 Dec 1991), and George Rennie CAMPBELL (1915-1996). Colin CAMPBELL, the sixth and last child born in 1925, sadly did not survive beyond a few weeks. He is buried with his parents in Anderson’s Bay Cemetery in Dunedin.

Gordon Campbell had progressed through the Post Office ranks from messenger, clerk, Assistant Post Master to become the Postmaster at Arrowtown. In 1917 he was appointed to a Postmaster’s position in Dunedin city, of a very much bigger postal facility – the North Dunedin Post Office situated on the corner of Albany and Great King Streets.

The Campbells left Arrowtown for North Dunedin and their new accommodation which was to be in the Post Office! Built in 1878, the ground floor of this very solid bluestone building was the postal office itself while the upper floor provided accommodation for the Postmaster and his family. For the Campbell’s this would be home for their next 15 or so years. Today, the old post is a well preserved heritage listed building. It was fully restored in 2013 to be an Annex of the Otago Museum, now used for displays and as a cafe and function centre.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Whilst living at the Post Office, eldest son Jim Campbell had finished his schooling and taken a job as a Clerk at the Dunedin Railway Station and moved into a place of his own. Moya (Maud) and Gordon Jnr. (Buttermaker) had both been married and they too had moved into private residences in Dunedin. Youngest brother George had also left school as soon as possible and returned to Arrowtown to be a farm labourer. This left only Philip (still in secondary school) at home with his father and mother.

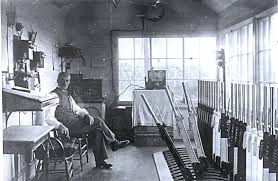

Once Philip Campbell had completed his secondary education in Dunedin, he first sought a job with his elder brother Jim and the NZ Railways (NZR) which at that time, had a very prominent profile in Dunedin. It was a major employer either at the Hillside Workshops for engineers, coach builders, painters, upholsterers and numerous other hands-on tradesmen, or it employed staff at the Dunedin Railway Station, the rail yards and out at Port Chalmers. Philip had not opted for any of the trade skilled jobs at Hillside but rather initially followed the lead of his elder brother Jim by joining NZR as a part-time Clerk. After two years experience, Philip (20) was made a full time Railway Clerk at the Dunedin Railway Station in 1931. Philip however sought a change of direction in his NZR career shortly after this. He wanted to do something more hands-on and so applied to be a Signalman, the person who operated the points (track change switching) and signals from a Signal Box in order to control the movement of trains. Signal boxes were usually found adjacent to a station. Philip was accepted and moved from the sedentary, pen-pushing work of a clerk, to that of an Assistant Signalman. Brother Jim also sought a change a few years later to become a Milk Roundsman.

Prior to 1935 Gordon Campbell’s health had started to decline to the point he finally had to give up his job as Postmaster, and the accommodation that went with it. The Campbells moved from their North Dunedin Post Office home to a hillside residence, just 400 metres away at 133 St. David Street. It was here that Gordon Campbell died unexpectedly on 11 Feb 1935 at the age of 48 leaving his widowed wife Maud and their five adult children, fatherless. Maud and Philip were also now the sole occupants of the house however Maud was spending her days alone while Philip was working and his Signalman training saw him spending periods of time away at some of the more rural signal boxes such as Mosgiel, Taieri, and Port Chalmers.

Rather than rattle around in a house on her own as well as try to maintain it, Maud accepted an offer from her son George to stay with him in Arrowtown, which she did. Her return to Arrowtown was most welcome; it was where she felt safest and had many friends there.

Gathering clouds of war

The Campbell’s, like every other family in New Zealand, by 1937 were well aware of what was happening on the other side of the world with regard to political posturing of the major powers, and the rise of the Nazis and fascism in Europe. The siblings were not unduly concerned of the implications as adjusting to life without their father and the care of their mother Maud was of greater concern.

Philip had managed to get a transfer to the Arrowtown so as to be nearer his mother and assist her and George whenever he could. It was a convenient move for NZR also as Philip would be able to cover both the Arrow and Queenstown Signal Boxes on an ‘as required’ basis.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Once the government announced all men between the ages of 16 and 60 would be required to have their names recorded on a national manpower register (a precursor to war), reality for the Campbell men started to sink in – they being of fighting age meant that at some point they would probably have to go to war! Only the luck of draw from the monthly ballot would confirm their fate to go or stay.

All major government ministries were required to start form territorial battalions into which their employees were put to undergo regular training and exercising conducted by cadres of regular soldier instructors. The railways being one of the largest employers in the country at the time formed two Railway Battalion, one in the North Island and one in the South. Philip was drafted into the 2nd Railway Battalion and held the rank of Corporal. Jim and George trained with the territorials of the Otago Regiment at the Kensington Barracks in Dunedin.

In the lead up to the start of war in 1939, Philip was moved twice by the NZR – firstly to the Roxburgh Station until 1938, then up to Timaru in 1939, and still further up country in 1940 to the Winchester Station which is about 30km north of Timaru on the main trunk line. His home however remained at the Lower Shotover in Arrowtown with his mother and George.

When volunteers had been called for to enlist with the Second NZ Expeditionary Force (2NZEF) Philip Campbell did not hesitate volunteered before the cut-off date in July 1940. All those who were not enlisted would risk bearing the stigma associated with the government’s re-introduction of Conscription under the Emergency Regulations Amendment Act. Conscription of men for active service in the Army took effect from June 1940 although volunteers were still being accepted for the Navy and Air Force service until 1941. Thereafter no choice was given: the Army was the primary destination for Conscripted men. Philip was still at the Winchester Station when he received his call-up to go into camp.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

9475 Private Philip Alexander CAMPBELL – 27 Machine Gun Battalion (27 [MG] Bn), 2NZEF was a volunteer and was enlisted at Burnham on 12 Sep 1939 as a member of 27 Machine Gun Battalion that would deploy to the Middle East with the First Echelon. This Echelon was being assembled and organised at Burnham, Trentham, Hopuhopu and Papakura. Training for officers and NCOs began on 27 Sep, and the main drafts of soldiers started their training on 03 October. Members of the Regular Force were assigned to the appointments of Adjutant, Regimental and Company Sergeants-Major.

On 5 Jan 1940, the First Echelon was ready to deploy to the Middle East. Embarkation commenced at the ports of Lyttelton, Wellington and Auckland. Seven days later, the Second Echelon began training.

North Africa

Cpl. Campbell’s son Fergus said his father almost never spoke of what he did during WW2. Given he was in a job that placed heavy reliance on maintaining a high degree of security (due to secret nature of the intelligence material the used and the operations they supported), it is hardly surprising. He did however answer a couple of questions over the years that his son recalls. The following was related to me by Fergus:

“While at Maadi Camp in 1940, Dad was returning from 10 days leave when he ran into his OC coming towards him along the road. The OC told Dad he had a new assignment and was to report to a certain officer. He reported to the officer and was asked if he was the man who had been a Signal Box operator for NZR? Dad told him he was and the officer told him he was no longer a Private Machine Gunner; he was now a Corporal in the NZ Corps of Signals with a staff of three – a Lance Corporal as his second in command, and two Signallers. In addition he was given a truck and trailer fully equipped as a mobile communications station with all necessary radio gear and a trailer of spares. What he was not told however was that the truck had dodgy brakes. Dad purposely neglected to mention this to his men but was sharply reminded while driving in a nose to tail convoy during a sandstorm. They were travelling at about 40 mph when he discovered the brakes had failed and so worked the gears and handbrake surreptitiously to avoid letting his front seat passenger know. The passenger, a Private who was a particularly ‘nervous Nelly’, would have had a meltdown if he’d known the truck had no brakes at all!”

Another event Philip had related to Fergus was while they were parked up in a desert camp. Fergus said “from their tent, the sound of approaching aircraft was heard. The four men rushed outside the tent in time to see a Spitfire ducking and weaving as it was being chased down by two Focke-Wulf, Fw 190 German fighter aircraft firing at the Spitfire alternately. They watched until all aircraft went out of sight, and returned to the tent. A few minutes later the sound of a fighter’s engines was again heard – back out of the tent went the team just in time to see the two Fw 190s ducking and weaving as they were being pursued by the Spitfire attacking them with cannon fire. They watched as one Fw 190 was hit and started to smoke as it plummet into the desert and exploded on impact. The Spitfire peeled away then executed a “victory roll” and speed away chasing the second Fw 190 until both were out of sight. That was the day’s entertainment over.”

When asked by Fergus if he had come under fire while in Africa, his father had replied, “Only twice – the first occasion was when I was walking through an olive grove and a single German Fw 190 overflew our position strafing indiscriminately as it went. It turned and repeated the strafing run. Parked nearby was a vehicle with an anti-aircraft machine gun mounted on it – I jumped on it and started firing in the direction of the plane.” Cpl Campbell being a trained machine gunner had fortuitously leapt onto the back of one of the LRGD vehicles, the only vehicles that had machine gun mounts for anti-aircraft work. He had got the gun firing in the direction of the approaching aircraft. Fergus continued “the attack was over in seconds and the fighter sped away. Dad didn’t know whether he had hit it but said the boys he was with had all dived for cover when the fighter started firing, bullets chewing up the ground around them. When the danger had passed, they leapt up and started cheering as the FW flew over to the jeep, pointing at the ground either side of the jeep – there were holes that was still smoking, cannon shell holes from the Focke Wulf – missed Dad by a gnats whisker, must have been his lucky day.”

Cpl. Campbell had a very lucky break I would say, Fergus continued:

“The second occasion was when Dad was providing communications in support of (classified) LRDG patrols. On one occasion he was supposed to rendezvous with a LRDG patrol in the desert. Travelling in a truck and trailer (with brakes!) they thundered along until they spotted the patrol, or what they thought was the LRDG. As they got nearer, bullets suddenly started coming their way. Fortunately they escaped with only a few holes in the truck and trailer. The LRDG patrol had turned out to be a German desert patrol that from a distance looked very similar to the LRDG vehicle and sandy coloured uniforms – the German patrol just happened to bisected their route, or Dad’s lot had made a map reading error in trying to find the patrol! Anyway, they managed to back-out of that situation very quickly and went like hell in the other direction”.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Red Cross – Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD)

No.3 New Zealand General Hospital (3/NZGH) was formed on 11 October 1940 and 48 NZ Army Nursing Service nurses were included in the staff. The unit was stationed at Trentham Mobilisation Camp and was prepared for service by 30 November but departure was delayed until 1 February 1941. They sailed aboard the transport Nieuw Amsterdam arriving in Port Tewfik on 23 March 1941. 3/NZGH was due to replace 1/NZGH, and arrived at the Helmieh hospital site on the day 1/NZGH departed for Greece.

Among the arrivals of voluntary nursing staff was Private Mary Fergusson, a VAD nurse who had offered her nursing services for the duration of the war. Mary had been the Matron of a children’s home in Gisborne when the war broke out. Being a trained Karitane nurse who had also had some St John training, she was asked if she was prepared to do some Red Cross training and become a Red Cross Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse. Mary agreed.

The Red Cross VAD recruited women with nursing training and first aid skills ostensibly to provide additional nursing assistance to the NZ Army Medical Corps (NZMC), be it in hospital ships or on the ground in Egypt or England. When the Women’s War Service Auxiliary was formed in 1940, a number of VAD women also enlisted to serve alongside the NZ Army Nursing Service (NZANS), including Mary. Within a matter of months, Pte. Mary Fergusson WWSA (VAD) was embarked on the HMNZT Maunganui at Wellington on 21 Nov 1941, bound for the 2NZEF General Hospital in Cairo, Egypt. On arrival, Mary was posted to No.3 NZ General Hospital at Helmieh, a suburb adjacent to the River Nile in central Cairo.

72113 Private Mary Bertha Fergusson – WWSA (VAD)

Mary Fergusson met Philip Campbell in early 1942. Philip and his three-man crew were entitled to use the British Army’s leave facilities as they were working for the British Army’s special operations units. One of the leave facilities was a houseboat named Arabia which was situated on the Nile near Helmieh and No.3 NZGH. Nurses from the hospital were often invited to have dinner with the soldiers staying on the houseboat and it was during one such invitation that Mary and Philip discovered that his cousin who lived in Gisborne, was a very close friend of Mary’s brother, Andrew Fergusson. During the evening there had been a discussion amongst the group about receiving mail from home. Both Mary and Philip commented that they didn’t get much, so they made an agreement that they would write to each other. This was the start of their relationship.

After some time of writing to each other, as they were too busy in their postings to see each other, they decided that their relationship was one they wanted to formalise and so became engaged.

Sometime later after it became common knowledge that they were engaged (much to the amusement of some of the ward patients as Philip was rumoured to be a woman-hater), Philip managed to get some leave which meant he could visit Mary who was working in at a hospital in Beirut. Mary knew he was coming and was worried that she might not remember what he looked like. She happened to be on duty in a ward when she saw Philip get off the truck he got a lift in, and was relieved. Unfortunately some of the patients who also knew him, called him over to the ward. They started egging Philip on for the two of them to kiss, but as they had never kissed before, Mary very firmly placed the broom she was using between her and Philip, and refused. The pair had several days together before Philip was due to go back to his unit, during which time they went sightseeing and bought an engagement ring.

Invalided home

Cpl. Campbell returned to the Divisional Signals HQ, reassembled his crew and was yet again assigned for ‘hush-hush’ desert operations with the LRDG for the next 12 months. In May 1943, he was warned to be ready for a secondment to the British Army which would necessarily involve work embedded with a British Army unit in North Africa, also with the likelihood of travel to England for the delivery of training. As he was about to return to Cairo and prepare for the secondment, Cpl. Campbell was stricken with Typhoid Fever. He was in a bad way and as a result his secondment was cancelled. After spending a week in a Field Hospital, he was invalided back to 3/NZGH in Helmeih. Unfortunately for Philip, Mary had been re-deployed temporarily to a hospital in Tripoli, Lybia. Mary had also become most concerned that she had not heard from Philip for some time before he fell ill, and even more so after she went to Lybia.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

After nearly 12 weeks in hospital, Cpl. Campbell underwent a Medical Board in October 1943 to assess his fitness to return to operations. It was discovered the primary cause for his illness was a missed round of vaccinations he was scheduled for, due to being away on desert operations. Philip was not fit to return to service. The Board decided he would benefit from a few weeks leave at home in NZ. Long Leave or OTL (Out of Theatre Leave) was a privilege accorded some of the longest serving (2 years plus) soldiers of the First Echelon. Following the leave Philip would return to Cairo where he would serve out the duration of the war in Cairo.

On Feb 10, 1944 Cpl. Campbell arrived in Wellington as part of a draught of Dunedin men serving in the Middle East who had been given a long leave (furlough) back to NZ. A long leave of three months was granted (where possible) after a minimum of two years service overseas. He was placed on Sick Leave pending a specialist medical board being convened to assess the effects of the Typhoid and the level of disability (this affected the amount of money he would receive from the Army). Philip went home to Arrowtown and awaited his appointment with the medical board. His homecoming was widely reported in the Arrowtown News section of the Lake Wakatipu Mail on 13 April 1944: “Cpl. P.A. Campbell enjoyed his leave in company of Mr & Mrs J. Shaw.” Mrs James Shaw was the sister of Philip’s mother Maud Campbell, who by then had moved from Arrowtown to 30 Strathearn Avenue in Wakari.

After attending the Army Medical Board, the specialists declared Philip to be no longer fit for active service on account of sickness. He would not be returning to Africa but remain in NZ. Resigned to his fate Philip sent Mary a telegram with a proposal, asking her to come home and to get married.

Meanwhile … back at the war

Following her temporary deployment to Tripoli, Pte. Mary Fergusson and 3/NZGH had been relocated to Bari in Italy. Mary and the group of VADs she had arrived in Cairo with were due to be repatriated to NZ via England, in August 1944. Mary was looking forward to the the trip as her mother was a Londoner and her father was from Dumfries in Scotland. There were a number of close relatives she had never met and was hoping to do so. However, Mary also had been having a few health problems of her own and as a result had been transferred from the wards to work in the hospital administration office.

Philip’s telegram eventually made its way to Italy and 3/NZGH. All telegrams in-coming and out-going were vetted by the Censor’s Office before on-forwarding to the addressee. In the case of Philips telegram, Mary’s Commanding Officer in Bari just happened to ‘intercept’ the telegram as it arrived and decided, it would be in Mary’s best interests to return to NZ immediately, and to say ‘yes’ to Philip’s proposal. The CO duly arranged for Mary’s return to NZ. Pte. Mary Fergusson – WWSA (VAD) was farwelled in fine style by her fellow VADs and NZANS colleagues as she departed from Bari in August 1944 on-board one of the hospital ships. Four weeks later, there on the wharf at Wellington waiting for the ship to arrive with Mary aboard, was fiancée Philip Campbell.

Philip and Mary were married a little over 12 months later at Gisborne on the 4th of November, 1945.

Medals:

2NZEF Service Overseas:

Cpl. P.A. Campbell ~ 12 September 1939 – 10 February 1944 = 4 years 59 days

Pte. M.B. Fergusson ~ 21 November 1941 – 4 November 1945 = 3 years 308 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

GISBORNE HERALD, VOLUME LXXI, ISSUE 21555, 7 NOVEMBER, 1944

MARRIAGE

<<<< 0 >>>>

Mr and Mrs Philip Campbell returned to Dunedin and settled into their first home at 33 Puketai Street in St Kilda.

Philip’s youngest brother George Rennie Campbell must have also been touched with the marriage bug because within eight months, he too married on Nov 30th, 1946 to Arrowtown resident, Doreen Gwendoline OAKES. Philip was George’s “Best Man.”

Phil and Mary’s first child was Fergus Ian Campbell, born at “Redroofs” on March 13, 1946. A daughter, Frances Mary TOD followed.

Note: ** Philip’s younger brother George also served overseas.

18607 Private George Rennie CAMPBELL, a Tractor Driver from Arrowtown, enlisted at Gore and entered the war as an Infantry Reinforcement in April 1941. He served in Egypt, North Africa, Italy and Crete. George Campbell returned to home and married Doreen Oakes in 1946. In 1947 George bought “Mill Farm” (now known as the Millbrook Resort) in Arrowtown from well known local identity Peter Butel. In Sep 1949, Philip and George’s mother, Mrs Maud Mary Campbell died on 03 Sep 1949, aged 64, at Mill Farm, their father having pre-deceased Maud at Dunedin in Feb 1935. George and Doreen Campbell had four daughters and eventually sold Mill Farm in the 1960s, moved to the Bay of Plenty where they ran a motor camp at Mt Maunganui for a number of years. Around 1970, the Campbells settled in Australia. George R. Campbell died at Attadale, Perth on 22 Dec 1996, aged 86.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Philip returned to NZ Railways as soon as his discharged came through. He was transferred from Dunedin railway Station to Wellington in 1947 during which their family lived in Naenae, Lower Hutt. In 1952 he was posted to stations at Matawhero in Gisborne, to Masterton in 1957, Wairoa in 1958, New Plymouth in 1961, Patea in 1964, back to New Plymouth again in 1965 and finally to Auckland Central Railway Station in 1966. His final posting was a ‘double hatted’ position – Assistant Station Master Auckland and Goods Manager Auckland – one of only four men in the country qualified to manage the Auckland’s Railway Goods Department which remains the largest and most complex in New Zealand. After 40 years of service with NZ Railways, Philip Campbell retired from NZ Railways in January 1970 and after some travelling, settled in Otaki. But why Otaki you may ask ?

Why Otaki ?

There were two compelling reasons to retire in Otaki: while Philip Campbell had no family connections to Otaki, he did have a connection which was equally as important to him, his Army ‘family’. Throughout the four years he had served in North Africa, Philip’s second in command had been 7840 L/Cpl Alan Tucker, NZ Corps of Signals (b:1914, Palmerston North). Alan was an electrician by trade with significant experience in radio repairs, a man Philip had very much relied upon for his expertise during their operations in the desert. They had been through thick and thin together, from extreme danger to larking about when on leave. Alan Tucker was a man Philip trusted like no other. These two had become great mates while serving together. The nature of their clandestine work with the LRDG on operations forged in them a bond that was special. Theirs was to be a life-long friendship of the sort that only those who have been in war together can know.

Alan Tucker** had returned to NZ earlier than Philip and had married his wife, Maida Ellen Frances CLEAVER (1920-2013) of Palmerston North, in June 1944. After the war, both families forged a lasting friendships and the families visited each other often. The Tuckers had moved into a house at Otaki Beach around 1947 which became a favourite with the children.

The second compelling reason Otaki was chosen was that when Philip retired from the NZR, his son Fergus was serving in the RNZAF, as was his son-in-law, Russell Tod. Mary had wanted to live somewhere that was central to make it easy for the family to visit. Otaki was also positioned on the main trunk line (central) and also had a pleasant climate. As Philip and Mary had already come to know Otaki well from their visits to close friends Alan and Maida, Otaki became their place of choice to settle. After 10 months of travelling around the South Island and a spell house-sitting, Philip and Mary temporarily moved into a rental home in Otaki in December 1970 while waiting for their house at 16 Freemans Road to be built. They moved into in April 1971.

The Tuckers in due course had moved from Otaki Beach to Rahui Road at “Otaki Railway” as it was known, a settlement of shops and houses that had built up around the State Highway 1 turn-off to Otaki’s main township towards the beach. Conveniently as it happened, when the Tuckers moved to Rahui Road, their house was a mere 500 meters from the Campbells (as the crow flies) which undoubtedly suited the old soldiers perfectly in their sunset years. Philip and Mary remained in their Freeman’s Road home until the late 1980’s when they downsized to a retirement unit at 35 Matene Street in the Otaki township.

Philip Alexander Campbell died at Otaki in 1991, aged 83. Mary moved to Hastings to be nearer her daughter Frances and husband Russell in April 1996. Mary Bertha Campbell died at Hastings in 2012 at the grand age of 98 years. Philip and Mary are at rest together in Otaki.

‘Lest We Forget’

Phil Campbell’s 2ic from North Africa and life-long friend Alan Tucker survived his mate by several more years, finally passing away at Levin in March 1998 at the age of 84. Both of these old soldiers and firm friends remain not far from each other in the Returned Serviceman’s Section of the Otaki Cemetery.

Note: This was indeed a story of coincidence as I discovered when Fergus related the details of his father’s employment to me. I also had lived in Otaki for a few years and whilst attending Otaki College in the 1960s, unbeknown to me Paul and Maida Tucker and their family were living barely 200 yards from a house my family’ was renting in Te Roto Road! The Tucker house faced directly up Te Roto Road, both roads bordering the Otaki Maori Racing Club’s track. I had first met two of the Tucker family members while attending Otaki College. I had never met Alan or Maida Tucker however their daughter Felicity had been in the same fourth form class as I. We had remained in the same classes in subsequent years until I left to join the Army following my sixth form year in 1969. Felicity’s older sister Christine Tucker had been a Prefect whilst I was in the Fourth. Their brother Malcolm and the two youngest Tuckers I did not know, perhaps my sister did. What a small world it is we live in!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I am indebted to Fergus’s sister Frances Tod for the in-depth detail that she has provided to complete this post including the photographs of Philip and Mary in uniform. My thanks to Alan Muntz for contacting MRNZ with Philip’s ‘diploma’ and personally returning it to Fergus – it was a pleasure to be able to get a prompt result.

The reunited medal tally stands at 309 ~ ephemera is not added to the reunited medal tally.