SA-1282 ~ JOHN HILL & SA-5033 ~ JACK HILL;

2/1209 ~ JOHN THOMAS TIMPSON

I received the following email from Lorraine of Rolleston:

Good afternoon,

I have come into possession of a 1st WW medal for Private J. Hill, No: 1282. I would like this medal returned to his family but I do not know if he has any relatives. The medal was in with my husband’s grandfather’s medals which we were sorting through for the family tree. If you can advise where I could send this medal to be reunited to family members I would greatly appreciate it.

Regards, Lorraine McK.

When I tipped the medal out of the post bag, to be fair it looked more like a beaten up coin than a medal. This medal had all the signs of having had a hard life – it was ‘dinged’ and nicked in several places, blackened and dirty, and its ribbon suspender bar and claw was missing. At a rough guess I would have said it had spent some time on a roadway and been run over numerous times.

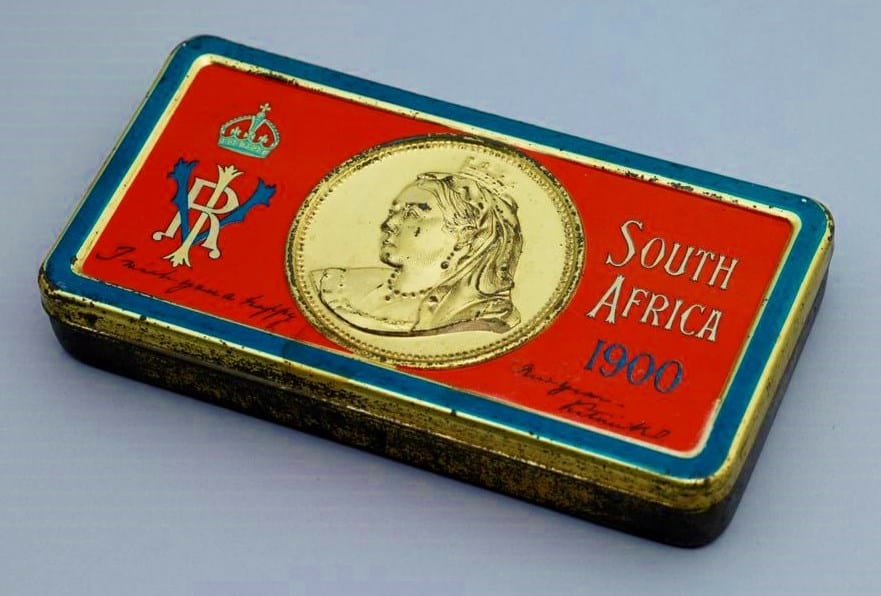

On closer inspection the words “SOUTH AFRICA” could just be made out through the blackened surface. In spite of the damage and blackness I recognised immediately what the medal had been issued for. It was a Queen’s South Africa medal, awarded for service in the 2nd South African (Anglo-Boer) War of 1899–1902, more commonly referred to as the Boer War. The regimental number of the recipient soldier was barely readable on the edge of the medal – a toothbrush and water to clean out the impressed numbers revealed who it had been named to: 1282 TPR. J. HILL. NZMR.

The research of this man started with the usual information extracted from a soldier’s digitised military file available from the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph website. The first indication I had that this might be a challenging case was in opening the website. It automatically went to another soldiers file who was not of the same name. I thought an error had occurred and tried again – same result. I opened the file I had been diverted to and found there were THREE files in one. There were three different service numbers and the file belonged to a John Thomas Timpson? I was looking for John Hill’s file? The files I had showed the soldier had served overseas on three different occasions, twice in South Africa and once during the First World War.

For his first tour of duty to South Africa, the soldier went as JOHN HILL (the man I was looking for – maybe it had been incorrectly loaded into Timpson’s file as does happen quite frequently with these digitised files). For his second tour to South Africa the soldier went as JACK HILL, and when he went to Egypt and France during WW1, he had gone as JOHN T. TIMPSON. To confuse the start of this research even search further, there were four men listed as “J. HILL” on the Contingent’s embarkation rolls, three of whom were on John/Jack Hill’s second tour of duty to South Africa!

The next curve ball I encountered during this initial assessment that added to my growing disquiet, was with the person Hill had named as his Next of Kin, the person to be contacted in the event Hill became a casualty. For his first tour of duty to South Africa, John Hill had nominated “J. HILL – Cousin, Kimberley” south-east of Levin in Horowhenua-Manawatu. Plausible I suppose but the chances of two cousins both having the same name I thought fairly remote – I became suspicious of a cover-up and that either the truth had been bent for some reason, or there had be some major stuff-ups in the administration of this man?

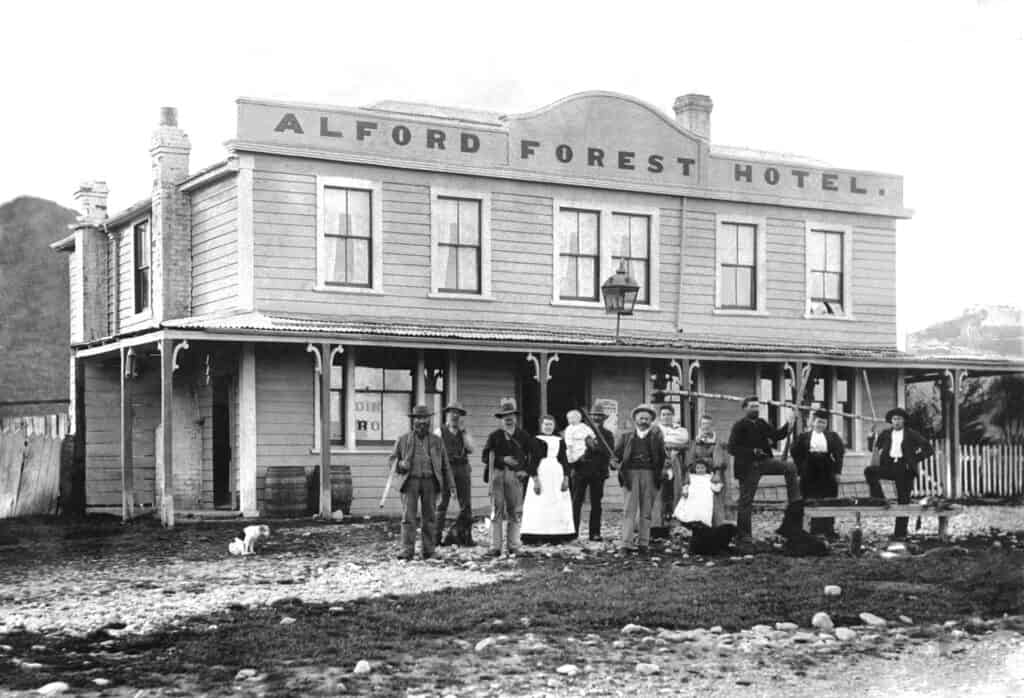

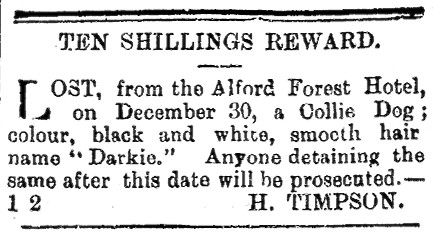

My quandary was further exacerbated with Hill’s Next of Kin nominee for his second tour of duty to South Africa. The file of JACK HILL recorded his Next of Kin as “George TIMPSON, Brother” whose contact address was, c/o Alford Forest Hotel. The Ashburton Electoral Roll of 1900 showed this person to be George Herbert Timpson, a resident of Alford Forest and the son of the Alford Forest Hotel-keeper and accommodation house licensee, Henry and Anne Timpson. Also residing at the Alford Forest address was Charles Henry Timpson, John Thomas Timpson and Ada Fanny Timpson. As I later found out, there were more children but these were not recorded since they were not yet 21 years of age. I found nothing unusual here but still nothing to indicate why JOHN HILL from Levin had cited George Timpson of Alford Forest as his brother – what was the connection? Perhaps George’s parents had adopted John; was he an illegitimate son of a Timpson daughter, or had he been born to a different mother, or father? These questions I needed to resolve if I was to understand what the Hill–Timpson relationships was in order to unravel what had started as a rather complex beginning to John Hill’s story.

Since the Timpsons featured so prominently in the Electoral Rolls, I decided to start with them to see if John Hill fitted into their family picture. From the information I had plus the available public records (BDM, Electoral Rolls and Censuses) I was able to re-build the Timpson family’s profile which took me back to their Northamptonshire roots. From this I was then able to trace them from their migration to NZ, arrival at Ashburton, Temuka and their settlement at Alford Forest and Mt Somers. One thing however that was abundantly clear after I had read the files and checked a couple of public records, was there were definitely no persons or families named “HILL” (other than John) associated with the Timpsons or indeed their extended family?

Without detailing the where’s and why-for’s here, to keep the events and chronology in context I will explain what I found as the story unfolds.

Note: To maintain the story’s context, I will refer to John Hill by the name under which he enlisted at each stage of his military service, until his return to New Zealand in 1918.

Northamptonshire

When Henry TIMPSON (1789-1856) married Ann EAGLE (1794-1862), they moved to where Henry found employment at Apethorpe, Northamptonshire. Henry worked for the Earl of Westmorland as a Shepherd until his death in 1856. Their sixth and youngest child, also Henry TIMPSON (1832-1898) born at Apethorpe, grew up working initially as an Agricultural Labourer then became a Shepherd.

Henry TIMPSON was 27 when he was arried at Kings Cliffe (2 km NW of Apethorpe) in January 1860 to 18 year old Ann (Annie) WHEELBAND (1841-1899) of Laxton, Newark (8 km east of Kings Cliffe). Together they produced a family of 13 children over the ensuing 23 years, five of whom did not survive beyond birth or a few years. In order of arrival their children were – Mary Lizzie Timpson (1861), Jenny Finetta Fanny Timpson (1863, 2yrs), Harry William Timpson (1865-1937 – went to live at Salmon Arm, British Columbia, Canada), Charles Henry Timpson (1867), Ada Fanny Timpson (1869), George Herbert Timpson (1871), Frank Timpson (1873, 0), John Thomas Timpson (13 June, 1874), Annie Eliza Timpson (1876), Frank Arthur Timpson (1878, 0), Edward Francis Timpson (1880, 6yrs), Lillie Groome Timpson (1881), Maud Lois Timpson (1884, 0).

Note: The names in RED indicate those children who either died at birth or within six years.

Henry’s sister Mary Ann Timpson had married James LOWETH and together they ran the “Wheel Inn” at King’s Cliffe. The 1861 Census described Henry as a Grocer and Shepherd. Subsequent entries show both Henry and Annie working at the “Wheel Inn” no doubt gaining experience which would later prove useful in running their own business.

By October 1865 Henry was listed as a Gamekeeper, working for varying lengths of time with different employers. The Timpson’s first five children were born in King’s Cliffe, with two more (names unk) at Woodeaton in Oxfordshire. Their eighth child, John Thomas Timpson, was born at Glapthorn, Peterborough back in Northamptonshire together with two more un-named siblings. Glapthorn is about 6 kms south of King’s Cliffe.

From here the family moved to Luddington where Henry was employed by the Duke of Buccleuch as his Farm Bailiff managing the tenant farmers (collecting rent etc) on the Duke’s estate. Two more children were born at Luddington before the Timpsons moved to Cheltenham in Gloucestershire where Henry and his son Harry went into business as Contract Gardeners. The Timpson’s last child, Maud Lois Timpson, regrettably did not survive.

Emigration

Ann Timpson’s brother, William Wheelband, had emigrated to New Zealand some years previously and had regularly encouraged his sister and brother-in-law Henry to consider moving to New Zealand. Henry had always been one to try and better his family’s circumstances and so made the decision to emigrate. The Timpson’s boarded the barque Langstone on 29 April 1886 (minus the two eldest girls who would come out later) and set sail for NZ. Henry paid extra for the family to travel as cabin passengers as was recommended by brother-in-law William Wheelband, rather than have to persist with cramped and unpleasant steerage berths for the next 90-100 days.

The family arrived at Lyttelton on 3 August 1886 and were quarantined in the immigration barracks until cleared by Customs and the Health Department. They then booked passage overland to Temuka. There was a great welcome from William and his wife Sarah when they arrived at Temuka. The Wheelbands, unable to have children of their own, delighted in the arrival of their young nieces and nephews, and Henry and Annie. Henry got the family settled in their own accommodation in Temuka where they would stay for the next five or so years. William had established a successful gardening and nursery business since his arrival, and so employed Henry and his sons until Henry had sufficient finance to pursue his aim of setting up a hotel and accommodation house in the district. Coincidentally and fortuitously, William had also been in the hotel business and was employed as a hotel broker when required.

Alford Forest – Mt Somers

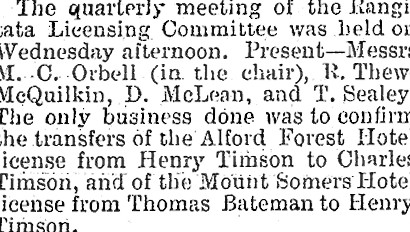

In 1892 Henry moved his family to Springburn in rural Ashburton and settled into a small makeshift home. On June 6, 1894 Henry made the journey to Geraldine to apply for the licence of an accommodation house, the Alford Forest Hotel (commonly referred to as the “Bush“). Once approved the Timpson family moved in. About 18 months later Henry put his two eldest sons in charge of running the hotel, recently married Charles Henry (25) known as Charlie, and wife “Nellie” Ellen (Horner) Timpson, and his brother George Herbert Timpson (21). An interim accommodation licence was issued in May 1896 for eldest son Charlie to manage the hotel while his Henry had his eye on another accommodation house not too far distant at Mt Somers, about 16km SW of Alford Forest. Henry’s application for the licence of the Mt Somers Hotel was approved in June 1896, the family remaining at Alford Forest until September 1896 when Henry and Annie with the help of their youngest son John Thomas Timpson (17) finally took possession from James Bateman, the previous tenant and licencee. In so doing, Henry also transferred his licence of the Alford Forest Hotel to Charlie who would then be able to legally serve liquor.

Both hotels thrived for the next year until Charlie Timpson’s financial management of Alford Forest Hotel turned pear shaped in July 1897. Licencee Charlie had got himself into strife by spending more than he was earning. This eventually played out in the Ashburton District Court on 1st October 1897 when after hearing all the evidence, Charlie was adjudged to be bankrupt! This automatically disqualified from being the owner of a business (holding a license) among other restrictions, for a period of years as set down by the court. Charlie could no longer legally run the Alford Forest Hotel and as a consequence, Henry made his second son George the manager and arranged for the license to be transferred into his name.

Charlie and Ellen Timpson left Alford Forest and moved to Staveley, about 8 km southwest of the hotel where Charlie turned to coal mining for an income. Ironically George joined him several years later and in 1912 was severely injured when half a ton of coal fell on him whilst mining in the Mt Somers Coal Mine. George recovered but was forever after affected by his injuries. In 1924, Charlie and fellow investor Joe Bright, applied for a 104 acre Coal Lease in the Alford Forest area and together began a commercially viable coal mine.

Mt Somers Hotel – sale or no sale?

A Mr A J Kelly visited Mt Somers when he learned that Henry Timpson was thinking of selling the licence. In discussion with Kelly, Henry indicated the price would be about £200, Kelly allegedly giving Henry £20 as a holding deposit. This money Kelly had borrowed from an Ashburton merchant on the pretext of needing to pay off some debts owed to his hotel landlord in Christchurch, before he could take possession of Mt Somers. Misunderstandings among the parties concerned resulted in Kelly defaulting on the purchase and appearing in the Ashburton Court by the merchant on a charge of borrowing the money under False Pretences. Henry was required to attend to give evidence as to his part in the saga. The upshot was the sale of Mt Somers did not proceed and the case against Kelly was dismissed. Henry’s health at this point began to fail, no doubt from the stress of Charlie’s bankruptcy of the Alford Forest Hotel and now the court case, which had not implicated him of any wrong-doing in any way. Henry decided he wanted out of Mt Somers Hotel and so made it known he was terminating his tenancy as the licencee.

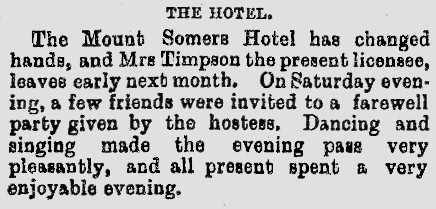

Mt Somers Hotel was renown as being one of the best accommodation houses in the area while the Timpson’s were running it however the events of the past 18 months had taken its toll on Henry’s health. Henry was feeling the weight of a perceived tarnished reputation after the Charlie’s bankruptcy of the Alford Forest Hotel plus the sale/no sale debacle with Kelly. He decided it was time to get out of the business and so pressed ahead with advertising his tenancy of Mt Somers Hotel. By March 1898, a Mr Petrie from Rakaia had committed to the tenancy of Mt Somers which was finally approved in September 1898. The Timpson’s would remain until the New Year when the new tennant would take over.

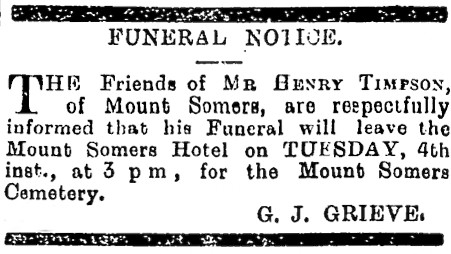

Two weeks later, exactly one year and a day after the court’s adjudication of Charlie’s bankruptcy, Henry Timpson died suddenly on 2 October 1898 at the age of 64 years. Annie was given permission by the Timaru Licencing Committee to act as Licencee in her husband’s absence, whilst funeral arrangements for Henry were arranged.

Annie Timpson with the help of son John Thomas kept the hotel operating as normal until February 1899 when the licence was officially transferred to her appointee, Frederick POWELL, a licensed hotelkeeper. A month later in early March 1899, whilst travelling by coach across the Hanmer Plains, Annie Timpson had a heart attack and died at the age of 50. Annie’s eldest daughter Mary Lizzie (Timpson) BLYTH was left to be the Executor of her mother’s Will whilst Charlie, George and John Timpson paid the required legal sureties. Thus the Timpson family ended its foray into the accommodation house business. Henry and Annie were both buried in the Mt Somers Cemetery.

War in South Africa

With the Mt Somers hotel under new management and the Alford Forest Hotel and his father and mother both deceased, John Timpson had no particular wish to stay around Mt Somers or Alford Forest. Besides, he was aware (as was everyone else in the country) that New Zealand was about to commit soldiers to a growing conflict that Great Britain had mobilised a large number of British regiments to fight in South Africa. New Zealand committed its support for the operation with a mounted rifles regiment, initially drawn from serving soldiers of the militia or territorial volunteers in NZ, many of who were former soldier migrants from British regiments. Additional replacement soldiers would be needed in due course and for these volunteers would be required. It was an opportunity for John to make some good money and participate in an adventure like no other. Without a word to anyone in the family, John left Mt Somers and headed north to see what he could find out about joining up for the South African stoush. Since nobody knew how long the war would last, and the government would be relying upon public donations to finance any contingent beyond the first two, John discovered once he got to Wellington that he would have to wait at least until a third contingent was needed. In the interim he needed work so headed up country, landing a labouring job in the Kimberly (Levin) area of Horowhenua. After several months he moved on finding work as a labourer for Mr Henry Coley, a carter of Foxton. Henry employed John as a shepherd on his property and with plenty of horse work, the situation proved to be ideal preparation for John’s intended enlistment. It gave him ample opportunity to brush up on his horsemanship and rifle shooting skills.

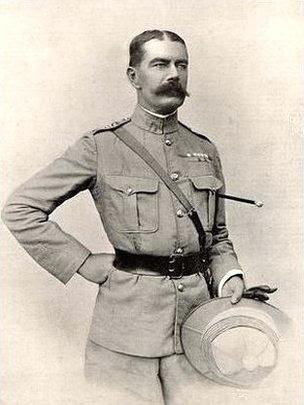

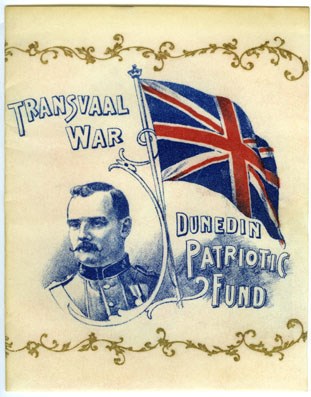

South African (2nd Anglo-Boer) War – 1899-1902

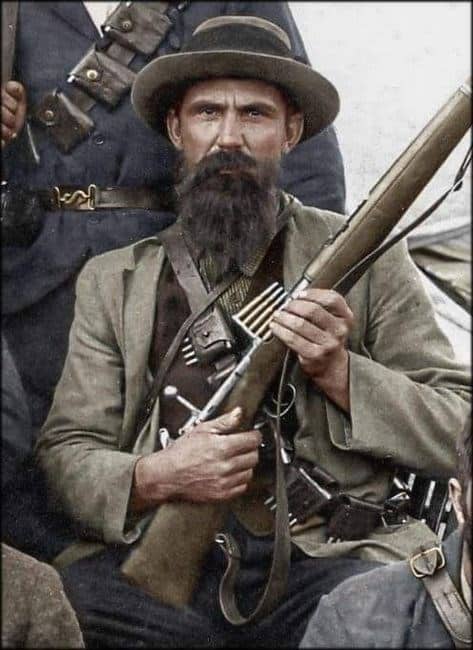

More commonly referred to as the Boer War, this conflict resulted from friction between the British Empire and the Boers of the South African province of Transvaal and their ally, the Orange Free State. The Boers, also known as Afrikaners, were the descendants of the original Dutch settlers of southern Africa. Britain had taken possession of the Dutch Cape colony in 1806 during the Napoleonic wars, sparking resistance from the independence-minded Boers, who resented the Anglicization of South Africa and Britain’s anti-slavery policies. In 1833 the Boers began an exodus into African tribal territory, where they founded the republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State.

The two new republics lived peaceably with their British neighbours until 1867, when the discovery of diamonds and gold in the region made conflict between the Boer states and Britain inevitable. Skirmishes had occurred which were building in intensity necessitating the deployment of several British Regiments to try and quell the deteriorating situation. New Zealand’s ties to Great Britain were strong and many of the volunteer and permanent serving soldiers from the British Regiments who had fought in New Zealand during the 1846-1866 land Wars, had settled in New Zealand after taking up the offer of a Land Grant to establish a home and small farm, an inducement for volunteers for that conflict.

New Zealand was the first member of the British Empire to offer help to Britain. Eager to demonstrate our commitment and loyalty to the Mother Country (Great Britain), New Zealand’s Premier Richard J. Seddon offered NZ troops for operations in South Africa to assist in crushing the uprising. Not since the NZ Land Wars ceased in 1866 had New Zealand’s young male population been involved in an armed conflict.

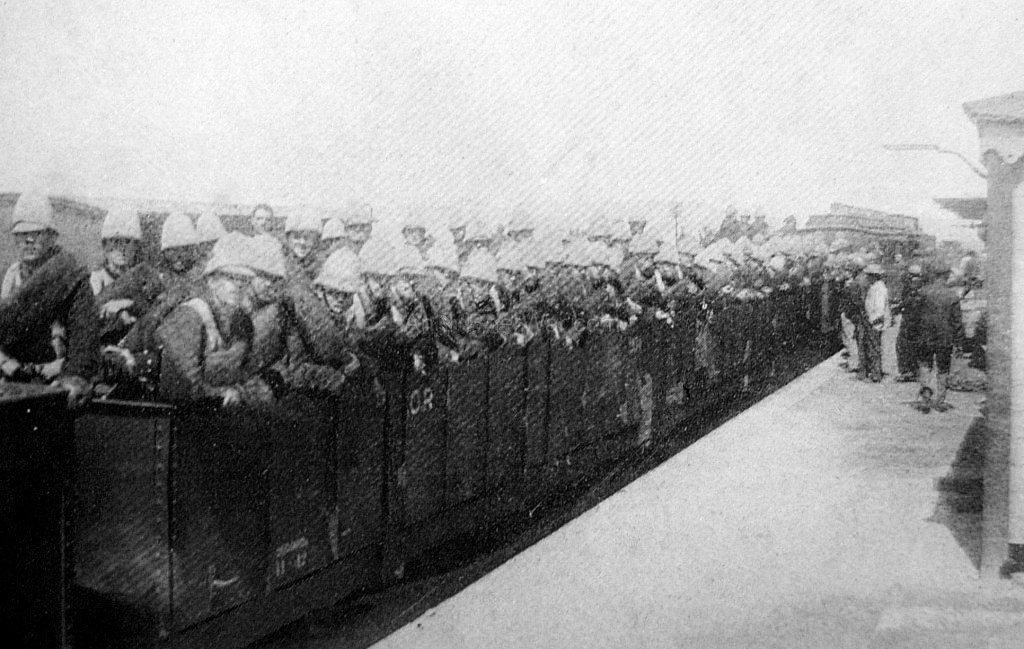

Ten contingents of New Zealand Mounted Rifle Volunteers (NZMR) totalling 6495 with 8000 horses were shipped from NZ to serve in South Africa between Oct 1899 and Aug 1902 (the term of service was one year), the largest proportion of representation from any participating British colony.

Recruiting

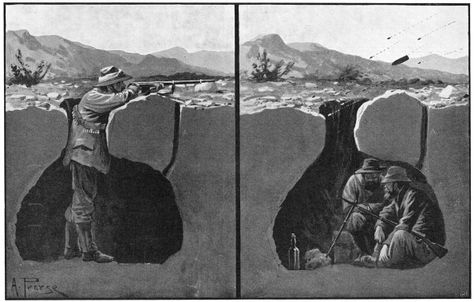

The South African War was the first in which New Zealanders would be required to travel overseas to fight the enemy (and die). New Zealand’s soldiers would be employed in this conflict as mounted infantry, i.e. ride to a specified distance of the enemy, dismount and take the fight to the enemy on foot while the horses were looked after by one of their number. Cavalry on the other hand were mounted and fought from the saddle with sword and pistol/rifle.

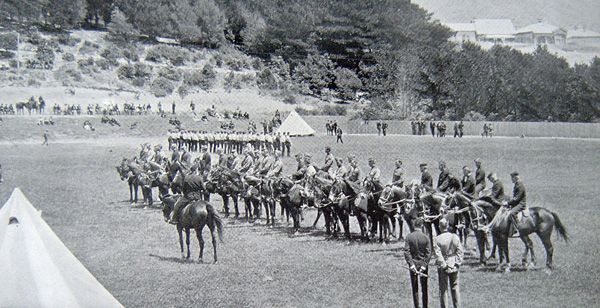

Permanent or part-time, all were tested against the criteria required as there were plenty of volunteers from which to select the best men. They were first pared down firstly by rejecting those who obviously too old, or with disabilities and diseases. Those who remained were tested for fitness and competency in horsemanship and rifle firing. At least three quarters failed the basic fitness and horsemanship. Some preference was also given to those volunteers who could provide their own horse, provided it passed the scrutiny of a vet. Those finally selected were sent to a training camp at Campbell Farm in Karori, Wellington for a fast few weeks of training and equipping.

Many who were rejected were known to have tried their luck by sailing to Australia or South Africa to enlist with other colonial units with in excess of 700 being successful.

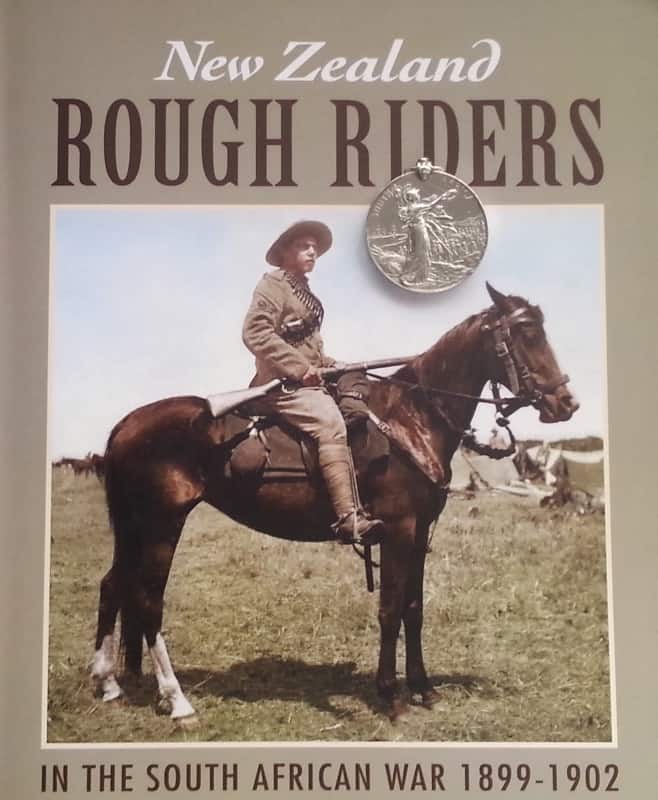

4th Contingent (Rough Riders) NZMR

The First contingent of 251 men of the 1st New Zealand Regiment as the unit was initially referred to, departed Wellington aboard the SS Waiwera on 21 October 1899 bound for Durban, South Africa via Albany in Western Australia. The Second Contingent of 266 (incl a 39 man Hotchkiss machine-gun detachment) was nearing readiness and departed on 20 January, 1900 aboard the SS Waiwera.

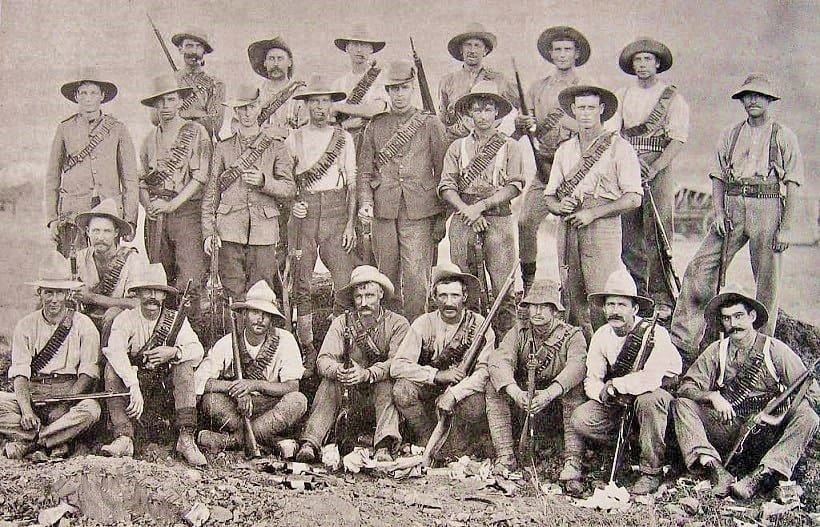

Volunteers for the 3rd and 4th Contingents, New Zealand Mounted Rifles (NZMR) were being assembled and would carry the sub-title of “Rough Riders” which simply indicated that both contingents would be made up of citizen volunteers who were reasonably experienced as horsemen and an ability with firing a rifle. Generally the younger and fitter were enlisted first, starting with 20 year old volunteers who could pass the riding and shooting selection tests – at 25 years & 8 months of age, 6 feet 9 inches tall and 12.5 stone, John Hill was a muscular and fit specimen of a man and a fairly capable horseman in all types of terrain as well as being handy with a rifle. While working as a shepherd he had the opportunity for plenty of practice both on the horse and with shooting rabbits and other game on Mr Coley’s property. When volunteers for the third and forth contingents were called for, John was at the forefront and accordingly had little difficulty with the selection tests.

Upon enlistment John did so under the assumed name of “JOHN HILL” and I concluded, provided a false contact name as his Next of Kin (NOK), the person to be notified in the event something happened to him. This person – his “Cousin, John Hill” he stated lived at Kimberley. Why he used the same name for his NOK as his own assumed name, I cannot answer – perhaps an administrative error or misunderstanding? John had only rarely communicated with his family since leaving Mt Somers and so maintained his intended enlistment for service overseas a secret. It would not be until well after John had left New Zealand that his letter to his sister Ada Fanny ANDREWS and her husband John in Temuka, would advise them where he was going and that they he had named them to be his Next of Kin. He would also advise them at this of his assumed name.

Trying to ascertain why John adopted an assumed name is difficult to know – I can only make assumptions based upon his circumstances at the time. Although John was of age (over 21 yrs) and therefore his own man for decision making purposes, I can only surmise that in being the youngest son of the family, he may have wished his intentions to serve abroad to remain anonymous from his family lest they try to prevent him from going for some reason. As the names of all soldiers selected for the contingents were to be published in the main newspapers around the country, it would have been difficult to avoid enquiry, or of having others who knew him from Ashburton, inform his family. His only other reason perhaps could be to avoid a ‘sticky’ situation with the law, a female or other however there is no evidence of any such impropriety on his behalf.

PS ….. AND there was no such person registered as “John Hill, Kimberley – cousin.” Shortly after he departed NZ John altered his NOK contact to his younger sister from Staveley, Temuka – Ada Fanny ANDREWS (nee Timpson) and her husband John Richardson Andrews.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

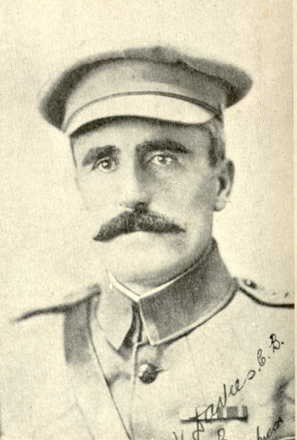

SA-1282 Trooper John Hill was attested at Wellington on 11 March 1900 as a Trooper of the 4th Contingent NZMR (Rough Riders). He would be sailing for South Africa in just 19 days!

With a strength of 467 soldiers and 400+ horses, the 4th (RR) NZMRs consisted of two full battalions, almost double the size of each of the three preceding contingents. Each battalion was divided into two companies with soldiers of No.7 and No.8 Companies from the North Island, and those of No.9 and No.10 Companies from Otago and Southland. Trooper John Hill (ex-Levin) was placed in the 7th Company along with a chap who in less than twelve month’s time would come to the nation’s attention, a blacksmith by the name of Trooper Billy Hardham. The result was of this organisation was that the Contingent had two commanders – Major Joe Sommerville (a NZ Land Wars veteran) commanded the North Island Companies and Major Frederick Francis had charge of the South Island Companies.

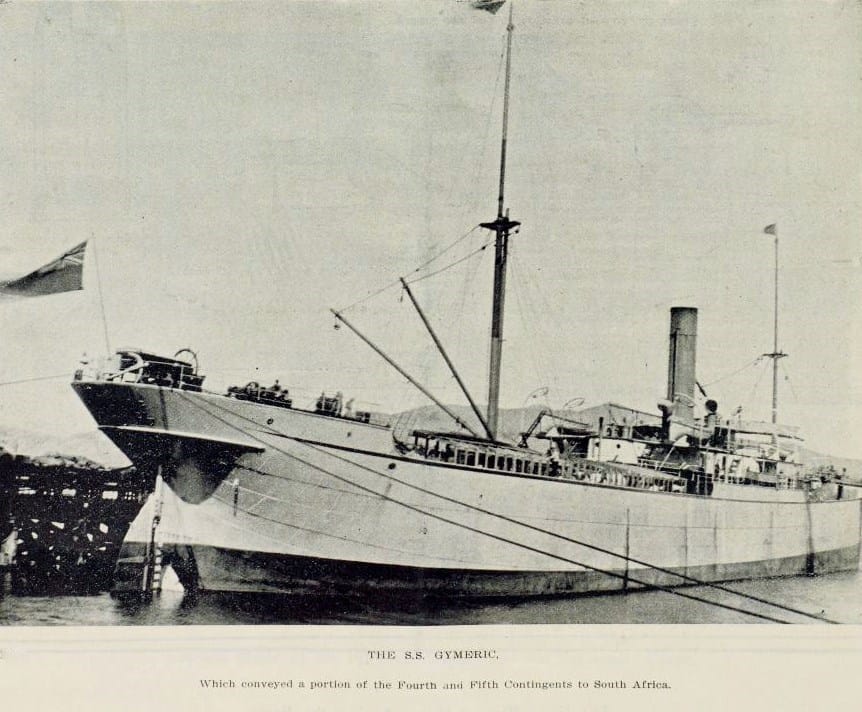

Companies No.7 and No.8 plus horses embarked on to the SS Gymeric at Lyttelton on 31 March 1900, and sailed for Durban. Companies Nos.9 and 10 were embarked on SS Monowai at Port Chalmers seven days earlier and set sail on the 24th of March. Both ships stopped briefly at Albany, Western Australia, long enough for a few soldiers to get themselves into trouble in some of the local watering holes, before heading to the port of Durban on the east coast of South Africa. On 11 May 1900 No.7 and No.8 Companies disembarked at Beira, a port town in Portuguese East Africa. The two companies, Nos.9 and 10, who had sailed ahead of 7 and 8 Companies departure preceded their arrival by 15 days, arriving on 26 April.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On arrival, the 4th (RR) NZMR Companies were re-named as follows: Nos. 9 and 10 Companies led by Major Fred Francis became A and B Squadrons, and Nos.7 and 8 Companies led by Major Joe Sommerville became C and D Squadrons.

The 4th (RR) NZMR started its service in Rhodesia followed by operations mainly in the western Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Immediately on their arrival sickness and fever spread through the men and horses, thought to have been caused by contaminated rainwater at Beira. The 4th (RR) NZMR headed for Marandellas in Rhodesia where they joined with the Rhodesian Field Force (RFF) under British command. The 5th Contingent NZMR would also join this group once it arrived in country. Together the 4th (RR) NZMR and RFF trekked 300 miles to Bulawayo which they covered in 21 days. Anticipating a Boer reception, they discovered the Boers had shifted. At this point C and D Squadrons were entrained to Mafeking while the remainder of the 4th (RR) and the RFF were placed under command of English Lt-Gen. Sir Frederick Carrington to conduct operations from bases in British–held territory in the northern Transvaal. The Contingent saw most of their service in the Transvaal, Rhodesia and the Cape Colony.

On 8 August the 4th (RR) NZMR entrained from Bulawayo to Mafeking. They then marched from Mafeking with a convoy of supplies when they encountered their first action from a large force of Boers. On 14 August, A and B Squadrons trailing ‘C’ Squadron (incl Tpr. Hill) and ‘D’ Squadrons were ordered to take a Boer position but encountered heavy fire after they had been allowed to advance within 15 yards of the enemy’s position. The ‘A’ Sqn. Commander Fulton was shot twice in the back and fell from his horse while Regimental Sgt- Major Dickey was shot through both thighs, and Trooper Sutherland also wounded. ‘Cat and mouse’ chases ensued with each out flanking the other until ‘B’ Squadron’s Commander Harvey ordered a bayonet charge. The Boers escaped but not before injuries had been inflicted on a number. This was a scenario that was to be repeated over the next five months while on the move to root out Boer positions and finding them to be more than a so-called ‘rag-tag’ bunch of militant farmers – they were equal in shooting skill, if not better, than most of the Empire’s invaders.

The 4th (RR) NZMR’s criss-crossed all three states over the next four months engaging pockets of Boers, capturing prisoners and their families, thousands of head of cattle and sheep, as well as hundreds of horses and mules, and a number of wagons.

As for Trooper Timpson, with the action in South Africa being reported in the newspapers at home, his family were clearly worried to the extent his brother Charles was instructed by his elder sister Mary Blyth to write to LtCol. Porter in Wellington asking for news of their brother since they had not heard from him in the eight months since he left for South Africa. There was no response on John’s file.

One of the most memorable events and a source of great pride for the 4th (RR) NZMR occurred on 28 January 1901 near Naauwpoort when Company Blacksmith and Farrier, 1251 Farrier-Sergeant William James “Billy” HARDHAM of ‘C’ Squadron carried out a courageous rescue of a wounded comrade. Farr. Sgt. Hardham and two troopers were part of a force of 20 ‘C’ Squadron troopers advancing on towards Boer positions when they came under intense fire from a concealed position at only 200 meters distant. They returned fire and were about to withdraw when one of the troopers was wounded and his horse killed beneath him. Hardham rode forward under fire to rescue the downed man. He dismounted and lifted the wounded trooper onto his own horse and bought him to safety while running along beside his horse with the reigns. For his actions Farrier-Sergeant Hardham was Mentioned in Dispatches (MiD) by General Sir Ian Hamilton and recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The Commander in Chief, Lord Kitchener had a different view and approved a subsequent award of the Victoria Cross on 04 October 1901. Billy Hardham was promoted to Farrier Sgt.-Major, and commissioned the following year as a Lieutenant in 1902. Lt. W.J. Hardham, VC returned to South Africa with the 9th Contingent.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

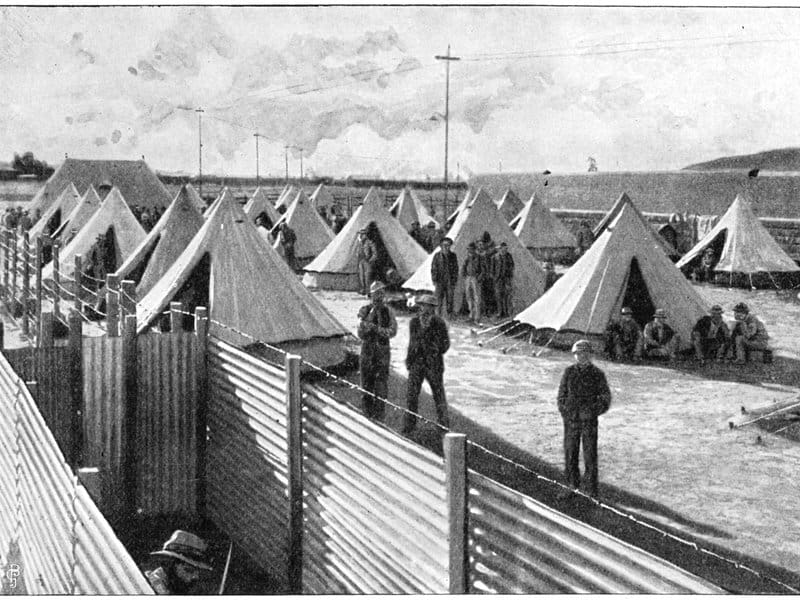

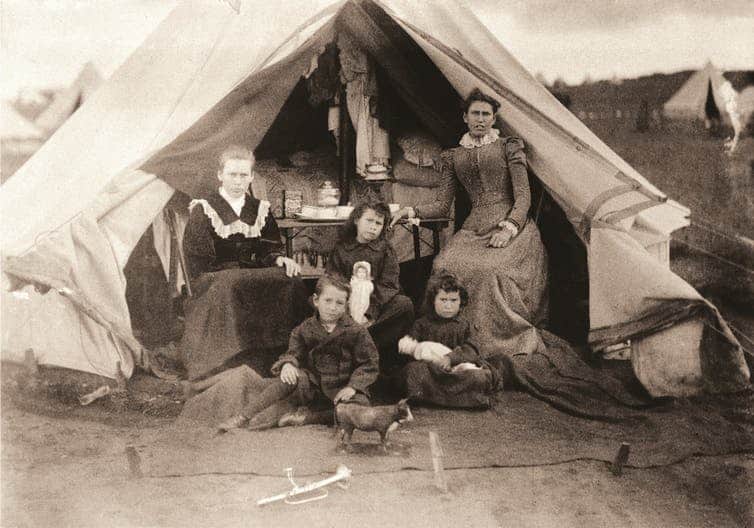

Beginning in 1901, the British had begun a strategy of systematically searching out and destroying these (Boer guerrilla units, while herding the families of the Boer soldiers into concentration camps. From March to May 1901, the 4th (RR) NZMR had unprecedented success at Klerksdorp and all but captured two Boer Generals de la Ray and Smuts, the former being wounded in the attempt. Come the end of this period of fighting, 135 Boer prisoners were captured, 3 artillery guns, 150 Mauser rifles carbines and pistols were taken and other valuable items, many of these by some very daring individual acts of courage.

In mid May, the 4th (RR) NZMR’s moved to Worcester in the Cape Colony to prepare for their return to NZ. After some R & R the 4th and 5th NZ Contingents left for Cape Town together and embarked the SS Tagus on 12 June. The ship arrived at Port Chalmers on 11 July with a Krupp’s 15 Pounder cannon and a Pom Pom 1 Pounder light field gun, a gift from General Kitchener in acknowledgement of the 4th (RR) Contingent and 5th Contingent NZMR achievements. Both contingents were disbanded on 21 July 1901.

Awards: Queen’s South Africa (QSA) medal with Clasps: TRANSVAAL, RHODESIA, CAPE COLONY

4th Contingent (RR) NZMR service: 317 days (10 mths+)

8th Contingent NZMR service: 182 days (6 mths+)

Total Boer War Service: 1 year 134 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Trooper John Hill returned to South Canterbury and to his sister Ada and John Andrews’s house in Temuka. He stayed with the Andrews while picking up the threads of his life where he had left off – a hard thing to do after such an action packed fifteen months of ‘kill or be killed’ action. He took on gardening for a while and then a job shepherding in Geraldine for a while, but compared with his time in South Africa, the sedate pace south Canterbury and shepherding made it difficult for John to settle.

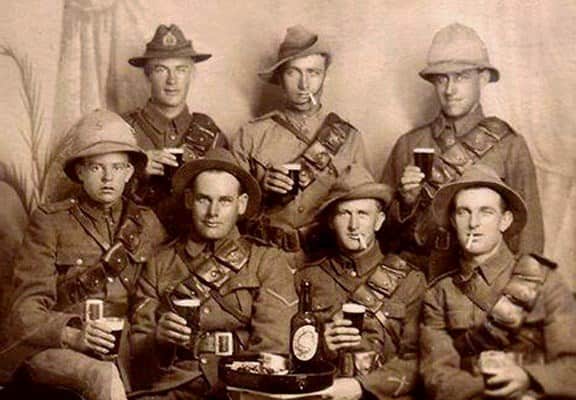

It had become the refuge of many veterans of the Boer War who had enjoyed the camaraderie of being at war together since there was little else for them to do after they returned, particularly in the rural areas. Together with the unemployed, the bored (PTSD of course was unheard of, resulting in many undiagnosed cases of ‘shell shock’), and the war ravaged, these veterans also turned to alcohol (much of it cheap and some poisonous) to help them cope with their experiences, and a pervasive sense of hopelessness. The accepted treatment in the day for those severely affected by battle shock or other mental incapacities including alcoholism, was that there was no treatment. The norm was to confine these incorrigibles in mental asylums as ‘mental defectives’ where the often remained until death. For men like Jack and others of his ilk of a stronger constitution, nothing quite equalled the adrenaline rush one got from battlefield action. Alcohol was just all part of the ‘game’ – fight hard, play hard however take over his life, it did in time. Fortuitously for Jack, towards the end of 1901 the opportunity for re-enlistment became a reality.

8th Contingent, NZMR

In December 1901, at the request of the British Government New Zealand agreed to provide sufficient mounted riflemen to constitute NZ Contingents Nos 8, 9, and 10. The 8th was the first to be assembled and would be the largest contingent to date with a strength of 1,120 officers and soldiers under the command of SA-1221 Colonel Richard Hutton Davies, a civil engineer and surveyor born in London, resident of Inglewood, Taranaki. It is worth noting that the Colonial Executive expressed the desire that the regiments should not be split up and separated as some of the earlier contingents had been, attached to British Regiments. This was to promote the sense of national identity and cohesion of the contingent. It also ensured NZ troopers were led by their own officers and not by some of the highly questionable British officer leadership previous contingents had experienced. Many were unfamiliar with and unsympathetic to ‘colonial’ soldiers and soldiering methods. When former Trooper John Hill (Timpson) heard that additional contingents were to be financed, he volunteered to re-enlist. Of 4000 volunteers who came forward 1,011 were selected. Troopers of his ilk were limited in number but high in demand. Being a seasoned veteran John had proven himself in combat with the 4th (Rough Riders) and was well reported. He was accepted almost without question.

Return to the Veld

The 8th Contingent NZMR organisational identity had been defined by the geographic origins of its Troopers – two Regiments were constituted, one to be known as the North Island Regiment and the other, the South Island Regiment. The North Island Regt. consisted of A, B, C and D Squadrons and the South Island Regt. of E, F, G and H Squadrons.

John Timpson (26) was re-enlisted for his second tour of duty on 5 January 1902. Since the Army had only known him as “John Hill” he remained so to avoid confusion. Because of his previous experience he would also go with the rank of Corporal and a new regimental number of his contingent. John was enlisted as, SA-5033 Corporal Jack Hill and irrespective of being South Island based, he was placed with A Squadron of the North Island Regiment (possibly because he had originally joined with many returning for second tours that he had served with as No.7 Company of the 4th (RR) Contingent).

The reason I discovered for his minor name change, was a pragmatic one in that there were no less than four men listed as “J. HILL” on acceptance rolls, three of these were in the 8th Contingent. Aside from being distinguished by his rank, John used the name “Jack” Hill to differentiate himself from others in the contingent with the same name initial and name which included a second JOHN Hill, a JAMES Hill and a JUSTLY Hill. If that was enough to cause identification confusion issues, there was also a man named THOMAS JOHN Hill – the reverse of Jack’s own birth first and middle names of “John Thomas”! Jack’s sister and brother-in-law, Ada and John Andrews, whom he had previously named as his Next of Kin while away with the 4th Contingent, were preparing to move to Auckland during the time he would be in South Africa and so, Jack named his Hotel-keeper brother George Herbert Timpson of the Alford Forest Hotel, as his Next of Kin.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cpl. Hill and the North Island Regiment embarked on the SS Surrey four weeks later on 29 Jan 1902 at Wellington. Two days later they were in Auckland picking up the remainder of the Regiment and sailed for Durban, again via Albany. The South Island Regiment embarked on the SS Cornwall at Lyttelton a week later on 8 Feb 1902 and caught up with Surrey at Albany, convoying together to Durban. Both ships arrived at Durban on 15 March 1902 where both Regiments were entrained separately for the 500 km rail trip north-west to the town of Newcastle in northern Natal. The journey was very uncomfortable as the troops travelled in open railway trucks expose to the sun and at times in the pouring rain.

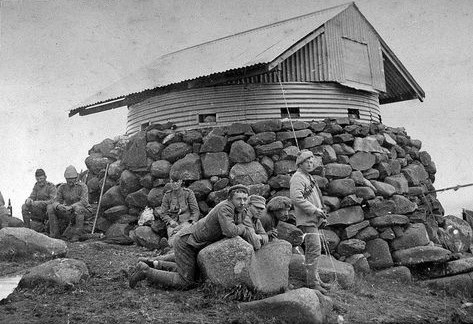

Arriving at Newcastle on 19 March, the soggy Regiments were kept busy preparing for the long trek ahead of them to the Orange Free State. All of the horses had to be shod in just seven days – they were finished in six! The 8th NZMR began their trek westward to Konigsberg on 3 April, going as far as Mollers Pass in the heart of the Drakensburg Range. The British had implemented a “scorched earth” policy at Lord Kitchener’s direction and were in the midst of a huge drive beyond the mountains in the north-east of Orange Free State when the Regiments arrived. The NZers were tasked with guarding Block Houses (fortified buildings to accommodate troops) and intercepting Boers but none broke their line. An inauspicious start to their war, however a cruel misfortune would shortly have a huge impact on the Contingent and indeed all the Empire’s Regiments in South Africa.

Machaive, Transvaal

Following an unsuccessful round trip of about 500 km in search of Boers in the Klip Valley in the Orange Free State by two squadrons of the South Island Regiment, the 8th NZMR reassembled at Newcastle and entrained for Elandsfontein on 12 April 1902. The train was to take the branch line to Klerksdorp where they would be mobilised under command of their own NZ officer, Colonel Richard Davies. Near a small station named Machavie on the line between Potchefstroom and Klerksdorp in the Transvaal, the train had been given wrongfully signalled the ‘all clear’ by the Stationmaster. As the troop train was descending an incline it rounded a blind curve and smashed into a goods train parked on the line.

‘H’ Squadron of the South Island Regt. was occupying the front trucks. The second truck was derailed on impact as the third and fourth concertinaed and landed on top of the first truck, crushing it. Those killed were all in the first truck as men were crushed, scalded by steam emanating from the burst engine boiler, and some were decapitated. Some who had been standing in or sitting on the side of the front few trucks and saw the crash coming, tried to warn others lying in the bottom of the trucks but they were ignored, as the others leapt to safety. The death toll was 16 men of the 8th Contingent killed, 13 from the first car with another 13 badly wounded from the first and second cars, several died from their injuries. A very big funeral was held at the Klerksdorp Cemetery a few days later attended by 200 Canadians, 600 Australians, 900 men from various regiments quartered at Machavie, detachments from the Seaforth, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders and Royal Artillery, 700 Boer refugees as well as members of the 8th Contingent NZMR.

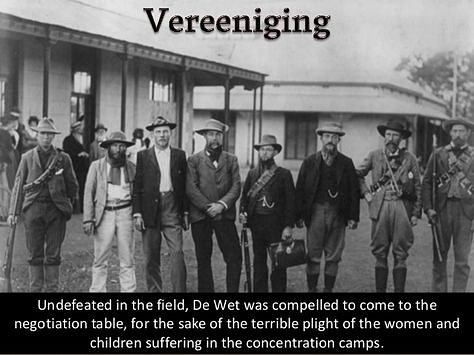

Ironically, the peace negotiations had also commenced on 12 April at Vereeniging, just south of Johannesburg. By mid May it was apparent the end of the war was close. The Boers had been comprehensively defeated by a British and colonial volunteer force which was superior in numbers, firepower and equipment. The 8th Contingent NZMR whilst their time in South Africa had been short, together with the contingent of Australian Bushmen, the 8th had made a significant contribution in bringing the Boer War to an end with the signing of a peace treaty at Vereeniging on 31 May 1902. On 17 June the 8th Contingent left Klerksdorp and made their way north-eastwards to Johannesburg where they handed in their horses and equipment, and entrained for Newcastle (Natal) before embarking their transport back to NZ a few days later.

The following quotation from the Dispatch of 1st June 1902 shows how arduous the 8th Contingent’s service had been, particularly in the last days of the war, and also bears testimony to the good work of the recently arrived Australians and New Zealanders, many of whom had been at sea for some weeks. Lord Kitchener, in referring to a great drive under General Sir Ian Hamilton, from about Klerksdorp to the Kimberley–Mafeking railway, said: “On 11th May the whole force closed in on the Vryburg railway, when it was found our captures included 367 prisoners of war, 326 horses, 95 mules, 175 wagons, 66 Cape carts, 3620 cattle, 106 trek oxen, and 7,000 rounds of ammunition,—this loss to the enemy constituting a blow to his resources such as he had not previously experienced in the Western Transvaal. Most of the prisoners fell into the hands of Lieutenant Colonel De Lisle, who, with the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Commonwealth Regiment, formed part of Colonel Thorneycroft’s column.

In reporting upon this extremely successful operation, General Sir Ian Hamilton desires to draw my attention to the enthusiasm and energy with which the troops met the exceptional hardships and work involved by lining out and entrenching themselves on four successive nights after long marches in a practically waterless country. On each of these nights every officer and man, after marching some 20 miles, had to spend the hours usually devoted to rest in entrenching, watching, and occasionally fighting. In this connection he draws special attention to the spade work done by the Commonwealth regiments—3rd New South Wales Bushmen, and the 8th New Zealand (Infantry) Regiment (as it had been referred to by the British). Every night while the sweep was in progress these troops dug one redoubt to hold 20 men every 100 yards of their front of six miles. The redoubts were so solidly constructed that they would have afforded perfect cover from artillery fire, and the intervals between them were closed by wagons linked together with barbed wire.

Sources: New Zealand Rough Riders: Richard Stowers; NZHistory.com; AngloBoerWar.com

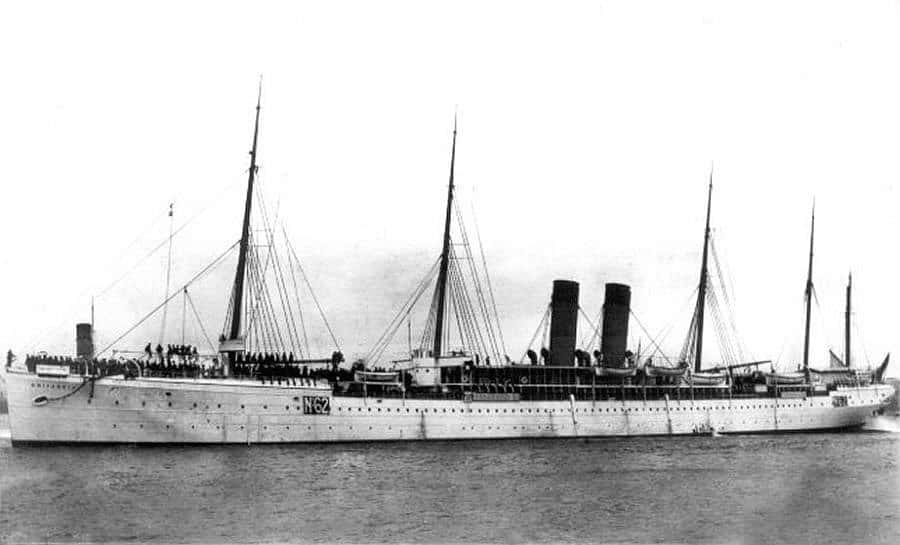

Homeward Bound

The 8th Contingent embarked on HMT** 62 Brittanic and on 5 July 1902, cast off and left Durban for Auckland. After three weeks at sea, Jack was taken ill on 1st August with a severe cold and admitted to the ship’s Sick Bay. His cold degenerated into Pleurisy and then Pneumonia. The ship’s doctor Surgeon Captain Richard Anderson after assessing his condition recommended his repatriation and discharge. Cpl. Hill remained in the Sick Bay for the rest of the voyage. Britannic arrived at Auckland on 7 Sep 1902, disembarked troops here and then went to Wellington and Christchurch. Cpl. Hill was disembarked from the ship’s Sick Bay at Lyttelton and moved directly to Timaru Hospital on 10 Sep 1902 where he stayed for another two weeks for testing. After nearly three months of hospitalisation, he was released on Sick Leave on 23 Sep 1902, pending his requirement to attend a military Medical Board. Although unwritten, it is clear from the comments on his file made by the doctor’s in reference to his repatriation and employment, that Jack had possibly wanted to remain in the Military Forces? After attending a Medical Board in Nov 1902 to assess his overall recovery from the Pneumonia and fitness for future service, any chance of future service ceased — his discharge was recommended.

Cpl. Jack Hill was officially discharged from the NZ Mounted Rifles on 15 November 1902, at which time he reverted to using his birth name, John (Jack) Thomas Timpson.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Awards: Additional QSA Medal clasps: SOUTH AFRICA 1901; SOUTH AFRICA 1902; Wound Stripe, Silver War Badge

Service Overseas: 182 days

Total service in South Africa: 2 years 316 days

New Zealand had sent a total of 6,495 troops in 10 contingents along with 30 NZ nurses and 20 teachers. Of these men 58 would be killed in battle, 11 would die later from wounds, 136 would die from disease, 26 would die from accidental deaths and 109 would be wounded in action. The men served with distinction and fought with bravery. When the last of the contingent’s returned home on the 17th of July, 1902 they had built for themselves a reputation second to none.

Note: ** HMT = Hired Military Transport. The SS Britannic having been a White Star Line luxury passenger liner, had been plying the Liverpool-Queenstown–New York route before it was requisitioned by the Royal Navy in August 1899 and converted for use as a troopship for the Second Boer War as HMT 62 Brittanic. In November 1900 Britannic had sailed to Australia with a Guard of Honour to represent Great Britain in the fleet review at Sydney Harbour to mark the inauguration of the Australian Commonwealth. During the period May 1899-October 1902, Britannic transported 37,000 troops to and from the conflict over the three years. After the South African War ended, Britannic was released from government service in October 1902 and returned to being a White Star passenger liner.

Return to Canterbury

Jack Hill returned to his sister Ada’s in Temuka and once fully fit again, took up residence in Geraldine for a time and a return to the hills shepherding. during this time Jack contemplated the idea of going into business as a poultry farmer. Together with his formerly bankrupted brother Charlie who was still at Staverley, they started the business called the “Poultry Supply Company.” Their venture got off to a shaky start mainly because money was short, not only for the Timpsons but also for most residents of the district who they had anticipated would be the bulk of their customers. This situation severely stretched the brothers financially and sales volume just did not eventuate. Jack found himself propping up the business with what he had earned in war service savings, but he was fast running out! He often consorted with his ‘faithful companion’ – alcohol, which did little to help matters. Poultry farming and the Timpson brothers were not meant to be. A couple of court appearances in Ashburton over Promissary Notes the were allegedly unfulfilled by the Timpsons. This resulted in Jack and Charlie coming ‘second’ in each case and finishing up substantially out of pocket, and their character in question. Clearly they did not have the heads for business and so the chicken farming idea went by the wayside. Furthermore, both were no longer able to obtain credit.

TEMUKA LEADER

MAGISTERIAL. CHRISTCHURCH. Tuesday, August 11, 1903.

Civil Cases; PROMISSORY NOTES.

(Before Mr W. R. Haselden, S.M.). (Mr Byrne) sued John Timpson (Mr Ritchie) for £12-2s, amount alleged to be due upon a promissory note given by the defendant. The defence was that the note had been given on condition that 100 shares in the Poultry Supply Company should be allotted to the defendant. The shares had not been received, and the note was consequently given without consideration. It was alleged further that when the note was signed it was stamped with a penny stamp, whereas the note produced bore a six-penny stamp. McAlpine swore that the six-penny stamps had been put on by him before the notes were signed, and the initials on the stamps were written in his presence. Judgement was given for the plaintiff, less £3 paid in. Judgement was also given for the plaintiff for £6-5s in the case, McAlpine v Charles Timpson, the circumstances of which were similar to those in the preceding case.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Change of direction

During a visit to Christchurch, Jack (30) had met 33 year old Christchurch born Sarah Rebecca COOPER (1879-1913) which within 18 months resulted in their marriage at the Christchurch Registry Office on 23 December, 1905.

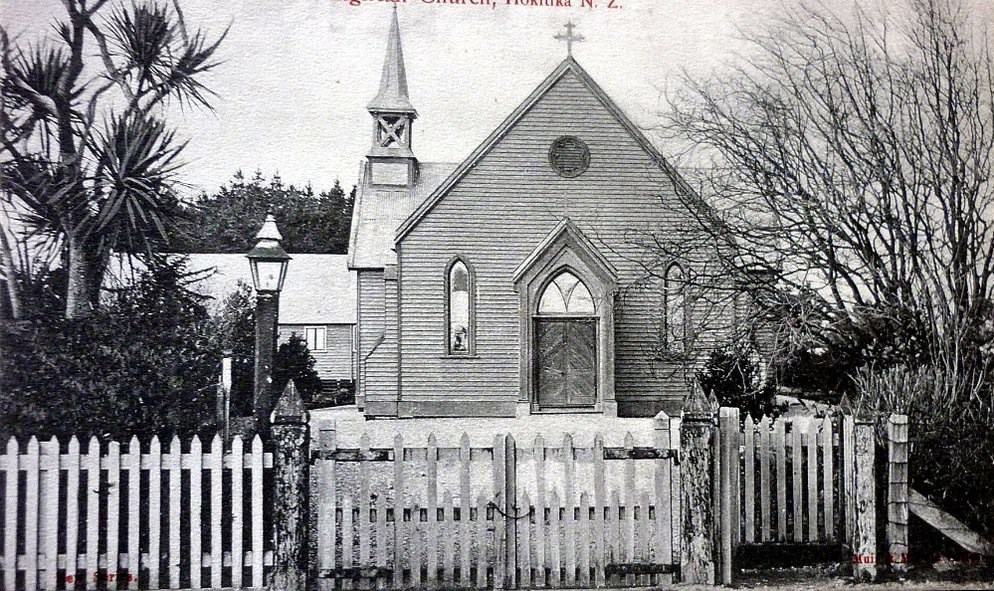

The attraction of the West Coast for the newly weds was strong as there were plenty of opportunities for work and to make money following the gold rush booms that had occurred at Charleston, Reefton, Hokitika and Ross. There were numerous companies on the Coast requiring miners, bushmen, timber workers and labourers, plus there were opportunities to acquire land. The prospect of owning a farm appealed to Jack and so the Timpson’s head to the West Coast to start their married life together, settling initially at Ross, 26 km south of Hokitika.

The other reason for going to the Coast was that Jack’s brother George Herbert and his wife Mary CARNEY who had married in 1895, left Alford Forest after the hotel burnt down. George and Mary had moved to Hokitika where he became an orchardist. When the Otira tunnel was started George and Mary moved to Otira, George joining the tunnelling men. Mary later moved to Sydenham in Christchurch with the family, prior to the First World War. After the war they returned to Hokitika and carried on until Jack died, after which George and Mary returned to Christchurch permanently.

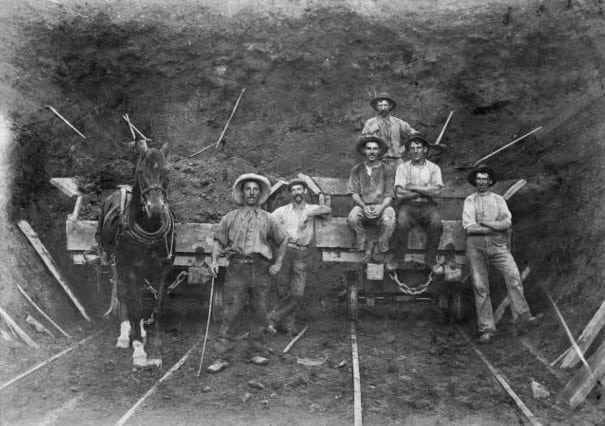

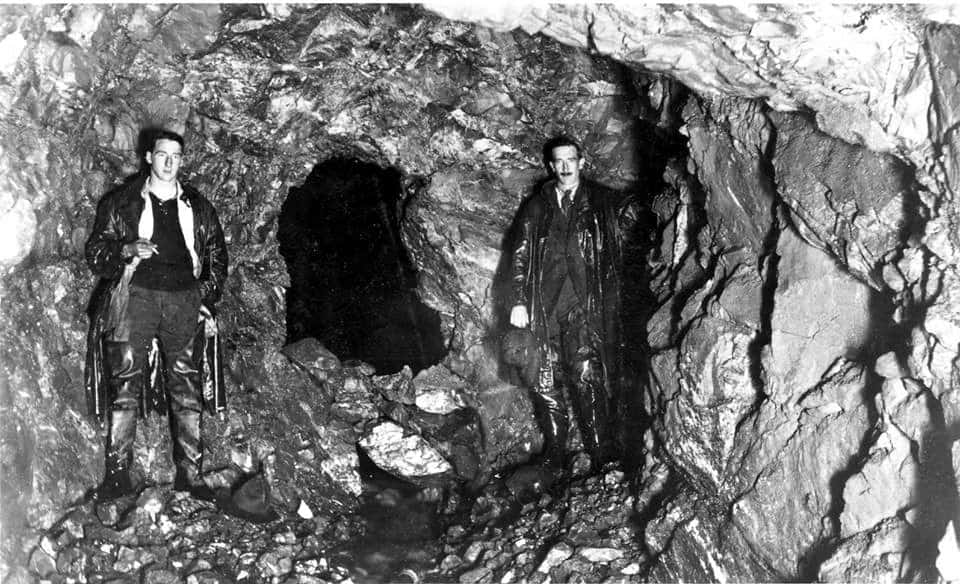

Ross, Westland

A small historic hamlet, Ross had been the centre of one of New Zealand’s richest alluvial goldfields in the late 19th century, with extensive underground mining and sluicing claims. Named after George Arthur Emilius ROSS who became treasurer of the Canterbury Provincial Council in 1865, the once small town of around 250 sprang up after substantial gold discoveries there in 1864–65 and had swelled to thousands of inhabitants. The surface gravels were rapidly worked out but gold was found beneath Ross Flat. Companies were formed to develop underground mines, one of which was the Ross Flat Company for whom Jack went to work on his arrival in Ross.

In 1909, New Zealand’s biggest nugget, the “Honourable Roddy Nugget”, was found in Jones Creek near the town. It weighed about 3 kg and had an varied history – it was used as a hotel doorstop, raffled to raise money for a hospital, gifted to King George V, and finally melted down to gild a royal tea set!

The mines at Ross continued to produce commercial quantities of gold however flooding of the underground shafts resulted in the last mine being closed in 1915. Whilst the miners gravitated to other gold fields such as those in Reefton, Waihi and Otago, or to other industries such as coal, timber and railway, alluvial gold still remained accessible at Ross. Productive quantities are still extracted to this day mainly by dredges of the three companies operating in the Ross area today.

Jack’s family & Otira

Jack and Sarah Timpson had a total of five children in their first five years of marriage. Their first child turned out to be two – Timpson twins! Anne Elizabeth (married – SMITH) and Christina Delia (married – DENT) were born at Ross on 27 March 1907. Whilst Jack and Sarah delighted in their new arrivals, Jack had plans to leave Ross and move his family to Otira.

The name ‘Otira’ in short means“O” (place of) and “tira” (the travellers). It is also short for ‘kua oti te haerenga e te tira’, which means ‘the journey over the alpine passes is at an end’. The Otira settlement in 1899 comprised two hotels, a school, two stores, a bakery and the train station as well as a handful of dwellings. The population was less than 40. The only reason for the existence of this isolated beech forest settlement, it was the start/end point of the only central overland route linking the West Coast with the East (Canterbury). The route consisted of a poorly maintained, pothole riven coaching track that traversed the Arthur’s Pass. The journey from west to east and Christchurch took an average of three days including stops for changes of horses, meals and overnight stops at the coaching settlements along the way. These were located at Kumara and Jacksons (the Otira side of the Pass), Otira itself, Bealey Flats (previously known as Camping Flat, and now the village of Arthur’s Pass), and Springfield. The track from Otira wound its way up and over a saddle pass that was straddled either side by the Bealey and Otira Rivers. The summit of the track peaked at an altitude of 2,425 feet (740 meters) and in winter often became impassable to horse drawn vehicles and even foot traffic. Deep snow, regular rainfall, waterfalls that cascaded over the track, land slips that often took part of the track into the river below, together with the added danger of intermittent rock falls, made for a trepidatious journey at best through the Pass in Spring or Autumn.

Aside from being a “to be avoided if possible” coach trip, and because of the large quantities of gold being extracted from the West Coast mines, a much quicker and reliable means of transportation that was not limited by load size able to be carried in horse drawn wagons, was needed to get the gold to Christchurch at speed. The Midland Line railway which ran from Greymouth through to Stillwater on the Otira side of the Alps, had been extended to Jacksons by 1894, and then on to Otira in 1899, where it terminated.

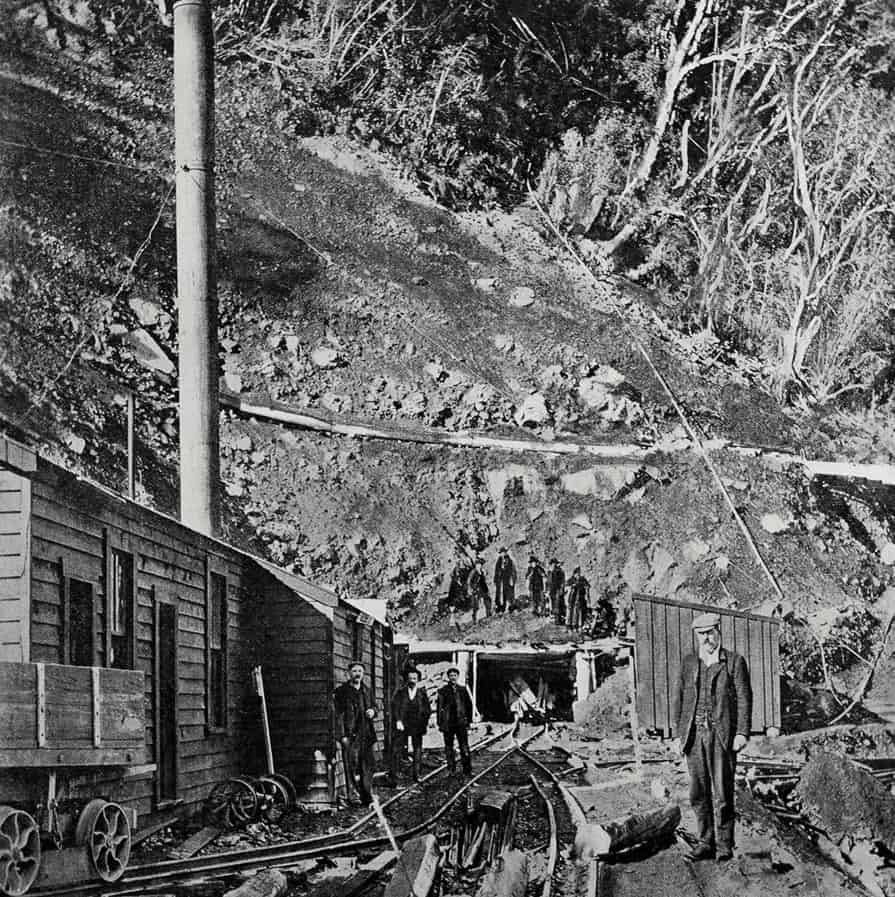

To meet the east-west demand for economic expansion, the government approved the building of a rail tunnel from Otira through the Southern Alps beneath the Pass to exit at Bealey Flats on the Canterbury side. As Otira was about 250 feet lower than the planned exit point, the tunnel would have to be constructed with an uphill gradient of 1:33 for a distance of about 8 kms. The tunnel would also reduce the coaching track distance of 15 km over the Pass, to around half that length. The Midland line would then be extended from Bealey Flats to its eastern terminus at Springfield from where trains would departed direct to Christchurch.

In 1908, Jack Timpson applied for and was accepted for a tunnelling position on the new project which promised long term employment, good conditions and financial returns for its employees. Jack relocated his family from Ross to Otira in early 1908. The construction of the Otira tunnel required hundreds of workers which saw the population of this previously isolated settlement swell rapidly to around 600 workers and their families. The towns facilities and housing also grew but initially were rudimentary at best – accommodation was started but many had to use tents until completed. Additional drinking establishments were quick to open, as well as general stores, a bank, extra blacksmithing services and bakers, a church, a hospital and a maternity home plus the conglomeration of other horseback ‘services’ the tunnelling community might require.

Carving a railway tunnel through the 5.3 miles (8.5 kms) of solid rock with pick and shovel was not a job for the fainthearted, but was necessary if the Coast was to be opened up to economic and social development. The contract to build the tunnel in 5 years was assigned by the PWD to the engineering firm of J.H. McLean and Sons who started drilling at the Otira end in October 1908, using the “drill and blast” method.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In July of the same year, Jack and Sarah’s third child and first son, John William Henry Timpson was born in the middle of an icy winter season.

WEST COAST TIMES.

BIRTHS. 27 July, 1908. TIMPSON.— On 27th July at Mrs Merrie’s Maternity Home, the wife of John Timpson, Otira, of a son. Both doing well.

One year on into the tunnel’s progress, Sarah Timpson, baby John Jnr. and the twins had endured their first (and last) full winter at Otira which proved both extreme and miserable. When Spring arrived, at Sarah’s insistence, Jack moved them all back to Gay Street in Ross where she and the children had better access to facilities, friends and help with the children in more bearable temperatures. Sarah was fearful that their young family would die in such dreadfully wet and cold conditions if they had remained in Otira. Jack did remain at Otira to work on the tunnel project, returning to Ross as and when he could.

Jack Timpson at 34 was strong and clearly not the sort of man who was backward in coming forward when it came to work related issues at the tunnel. His war service with the “Rough Riders” in South Africa had taught him the necessity and value of looking after his men and so, he became an effective advocate for the men working on the tunnel. As a result, he soon found himself elected to the Miners’ Union Executive at Otira. One of the major issues of the day was the re-election of the incumbent NZ Premier (title late changed to Prime Minister) Richard John Seddon, and for who John Timpson as a Union official, had been appointed to be one of the Scrutineers at the Otira Polling Station in November 1908. A scathing letter of criticism sent to the Editor of the West Coast Times was published on 28 Nov 1908, alleging improper polling conduct by one of the officials on polling day:

UNFAIR TACTICS

(To the Editor.)

SIR,— l feel that in the public interest attention should be pointedly called to the altogether improper conduct of Mr Gustave Haussmann while acting as Deputy Returning Officer at Otira on Tuesday, the 17th inst. Mr Haussmann, in the presence of myself and eight others at O’Malley’s Hotel, said he could definitely prove that Mr Michel had a dozen paid canvasers (whom he could name) in the Otira and Grey Valley line in connection with his candidature. Mr Haussmann, by spreading such a false report which, he could not substantiate, showed a bias against Mr Michel’s candidature in favour of Mr Seddon, which obviously proves him to be unfitted to fill the judicial position of Deputy Returning Officer. He ….. etc, …..etc……, and in the interests of political purity, I feel impelled to raise my voice against it with all the force in my power. Men like Mr Haussmann, incapable of taking an impartial stand in such office, should never be appointed to them.

I am, etc. Jack E. Jambs, Otira, Nov. 28, 1908.

Mr Haussmann clearly affronted by this criticism had sent Jack as one of the official Scrutineers at the Polling Station, the following article to which he replied. Haussmann then sent both to the Editor of West Coast Times who published them (as written here). Jack, as both Union Official and a Scrutineer during polling, handled this in a most adroit manner. The following will give the reader some idea of Jack Timpson’s ability to succinctly deal with sticky situations at Otira:

WEST COAST TIMES.

A WORD IN REPLY. — 5th, December 1908.

(The Editor)

SlR, — A copy of your paper dated November 28th, containing a letter from “Jack E. James” and headed “Unfair Tactics.” I have sent to Mr John Thomas Timpson of Otira. To-day I received the following reply : —

“Yours of the 28th inst to hand, also West Coast Times —

Re Mr Jack E. Jame’s letter, I find on perusal it has nothing whatever to do with your conduct while at the polling, and casts no reflection as such, and I again state that the poll was carried on in the fairest manner on both sides, but what occurred after the above I do not know anything about — You can make use of this letter if you desire”

— I beg to remain, yours truly, John T. Timpson.

I may mention for the information of the public that Mr Timpson was Scrutineer for Mr Michel and was present in the polling booth from 5am till all left the booth about 7 pm. Further comment is needless.

I am, etc. G. Haussman

Aside from the election issues at Otira which caused trouble among the workers and their own politics during the first year of tunnelling, labour troubles had also bedevilled the tunnel project – union leaders of the day, Bob Semple, Paddy Webb and Tim Armstrong promoted strikes and persuaded union members to work elsewhere other than at Otira. This contributed to a chronic shortage of suitable labour which in its turn brought poor productivity, a rise in accidents, and not least, the rise of the parliamentary Labour Party. The progress on the tunnel had been pitifully slow due in part to the hardness of the rock as well as the labour issues that Jack found himself in the forefront of dealing with. Here is just one example of the type of problem the Union Executives had to deal concerning the regular disappearance of miner’s lamps, always widely reported in the national papers:

WEST COAST TIMES.

19th, August 1909. (By Telegraph—Special to the Stat.)

TROUBLE AT OTIRA. AN ABORTIVE CONFERENCE.

OTIRA, This Day. The men held a meeting last night to discuss the situation.

Owing to the unsatisfactory reply from Mr McLean, [the contractor] in not allowing the matter to be settled by the Conciliation Commissioner, they have decided to put the matter before the Executive of their Union, a special meeting of which has been summoned. Until their decision is known, all work will cease.

The men have discontinued the practise of going up on their respective shifts, as there is now no occasion to do so, after lamps [the miner’s lamp each man was issued while in the tunnel were going missing!] being refused two or three times. Mr McLean, to affect a settlement, will now have to deal with the Union direct.

The men in Otira at the present time, working inside and outside of the tunnel, are as fine a body of men as could be got together. They are men that understand the class of work thoroughly. In view of the fact that last Saturday was pay day, one sees very little abuse of strong drink. The men are keeping sober and orderly, which should demonstrate to the outside public the class of men who are affected by the trouble.

At the meeting yesterday, Mr Gavin for the Contractors, Mr Mosten (Labour Bureau), Messrs Semple, Lagan and Timpson (for the men) were present.

It was urged by Mr Lagan that the matter be left to the Conciliation Commissioner to settle. Regarding tin lamps, he said that the men were prepared to have all lamps numbered and failing any man not returning the lamp issued to him he believes is responsible for it, the men not to take the lamps away to their huts or to trim the lamps themselves. Regarding the seven hour shifts, Mr McLean is adamant. The Line will only pay us for seven hours. The employee’s representatives state that if the men worked till 12 o’clock on Saturday night, it would be Sunday morning before they would leave the tunnel. One has only to look up the laws of the country, they add. to see that they would be broken if the men worked as is wanted. In the afternoon in surrounding districts men do not work till midnight on Saturday or start before 1 am on Monday morning. It is contended that the men’s demands are only just and reasonable, and, as the gentlemen who interviewed Mr Gavin yesterday pointed out, they were not there to represent the waster or any man who would wilfully damage or destroy property of the Line. By introducing the numbering system and excluding a man coming off shift, the firm would be able to catch the man who loses or destroys the lamps. The men hold meetings twice a day and all seem anxious to resume work immediately but they strongly object to the condition which Mid Line wishes to impose on them.

INANGAHUA TIMES.

The Otira Difficulty. —21st August, 1909.

The deadlock at Otira still continues. One hundred and twenty men working in the tunnel are affected, the position is best exemplified by the following wires which have passed through the Miners’ Union office.

– To Timpson, Otira—Executive endorse stand men have taken and decided to give all possible support to members. Hold possession of huts until evicted. Advise men not to claim wages owing for the present Executive expect men remain orderly and firm under any circumstances. Executive is appealing for the support of the Federation and expect ……../

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

With progress on the tunnel difficult and slow, the contractors (McLean & Son) asked to be relieved from the contract in 1912 which had financially ruined them – the tunnel had cost over twice the contract price of £599,794 ($1,200,000). The government could not find any other tenderers to complete the work so it was undertaken by the Public Works Dept (later known as the Ministry of Works). The government also considered halting construction for the forthcoming World War I, but the Imperial Government requested that work should continue in case the German navy blockaded the West Coast ports used for coal shipment.

The arrival of Lucy Mary Violet ROSE (b1910) also preceded the Timpson’s move from Ross to Livingston Street in Hokitika. Sarah’s health was not the best and with Jack still working at Otira, it seemed like a logical move. Jack and Sarah’s last child, Rebecca Cecelia Timpson was born at Hokitika in April 1913. Seven months after Rebecca’s birth, Sarah Timpson died of complications at the Westland Hospital in Greymouth; she was buried in the Hokitika Cemetery. Jack was bereft, and somewhat understandably, alcohol again became his comfort.

WEST COAST TIMES.

DEATH. — 07 Nov., 1913.

TIMPSON—At Westland Hospital on November 5th., Sarah Timpson of Hokitika, late of Christchurch. Aged 33 years.

FUNERAL NOTICE. — The friends of John Timpson and of his late WIFE (Sarah) are respectfully invited to follow her remains to the Cemetery. The funeral to move from his residence, Livingstone Street, THIS (Friday) AFTERNOON at 2 o’clock, and St. Mary’s Church at 2.30.

H. A. THOMPSON, Undertaker.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

First World War

The assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand of Austria at Sarajevo in June 1914, precipitated war by bringing the key European alliances of Germany and Austria-Hungary into conflict with the Franco-Russian alliance. These had the net effect of drawing the Empire, Japan and USA into the conflict. Within a matter of weeks volunteers were being called for to fight for King and Country. Jack Timpson, who by this time had returned to the Ross Flat Mining Company, was forty years, six months of age and fighting fit. The experience he had gained in South Africa as a “Rough Rider” gave him a distinct edge over those half his age who had initially flocked to the recruiting stations. Jack was also in need of money and so enlisted for service with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force NZEF).

After his wife’s burial Jack leased the land he had been using in the vicinity of the Hokitika racing course. With five children under six years of age to consider, he was not able to work and give proper care to the children and so he did the only thing he could under the circumstances. With the help of his late wife’s family, he took the children across to Christchurch and placed them in the care of the Mother Superior and Catholic Sisters at Nazareth House in Sydenham.

Jack then reported to Trentham on 12 December 1914 where he would spend the next 12 weeks in training as an artillery gunner. He would be joining the 2nd Brigade, NZ Divisional Artillery. Jack was Attested into the NZEF on 30 December 1914, committing himself for the duration of the war. On this occasion he enlisted under his birth name, John Thomas Timpson – there was no longer any reason for any subterfuge. Jack recorded his brother George H. Timpson, proprietor of the Alford Forest Hotel, Ashburton, as his Next of Kin.

Gallipoli, 1915

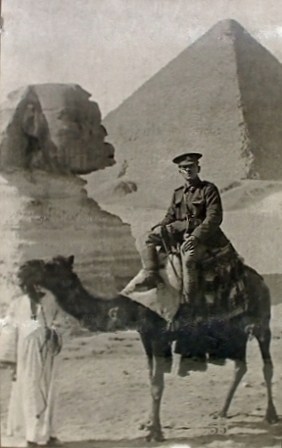

2/1209 Gunner John Thomas TIMPSON – No.5 Battery, NZ Field Artillery – 4th Reinforcements left Wellington on HMNZT 22 Knight Templar and sailed for Suez on 17 Apr 1915. Disembarking at Suez on 25 May, the Artillery Reinforcements were transferred by ferry boats though the Canal to the port of Alexandria, and overland by train to Zeitoun, the NZEF’s training camp in Egypt which was located 9 km north-east of Cairo. Directly opposite Zeitoun across the other side of Cairo to the southwest, was the Australian’s Mena training camp.

Training was the order of the day and Zeitoun Camp was abuzz with preparations for the proposed Landings at Gallipoli in April. On 15 June, Jack while still at Zeitoun, had a brief reunion with one of his nephews, his brother Charlie and Ellen Timpson’s boy, Private Leslie Timpson who had arrived with the Canterbury Infantry Battalion’s 5th Reinforcements in early April. After weeks of training on the guns, Jack had been rendered deaf and was admitted to Cairo hospital for a week in July. Once out of hospital and able to hear again, he readied himself with the NZ Field Artillery Reinforcements for embarkation to the Gallipoli Peninsula.

On 20 August, No.5 Battery of which Jack was now a member, was embarked at Alexandria bound for the Dardanelles to support the ANZAC forces that had landed on 25 April 1915. The Australian 2nd Division was also to be landed on 20 August, just in time to support the two major offensives that were due to start the following day. The Battle of Sari Bair, also known as the ‘August Offensive’, would be the final attempt by the British to seize control of the Gallipoli Peninsula from the Ottomans. The final ‘big push’ of the Gallipoli campaign was the Battle of Hill 60 and involved an ANZAC force of around 4,000 troops attacking to secure key defensive positions for the Sulva Bay landing. A bloody and costly venture that after eight days of intensive fighting and killing, failed to dislodge the Ottomans from the Peninsula – the cost to the ANZACs was more than 1,100 casualties.

His time on the Peninsula must have been an emotional roller coaster for Gnr. Timpson. Barely had he arrived than he had to make arrangements for money to be sent for the care of his children at Nazareth House. From Gallipoli on 30 Sep 1915 Gnr. Timpson made application for a “Special Allowance” which was available to NZEF soldiers for the care of their children. This he requested be made payable to the Mother Superior at Nazareth House. Not two months later, just to add more heartbreak to his circumstances, November 5th would be the second anniversary of his beloved wife Sarah’s death. Jack arranged to have the following published in the West Coast Times in memory of his dear wife Sarah:

WEST COAST TIMES.

IN MEMORIUM. TIMPSON.

— 6th., November, 1915. In loving memory of Sarah,

beloved wife of John Timpson,

who passed away on November 5th, 1913.

R. I. P.

The flowers that grow upon your grave

May wither and decay,

But fresh and green within my heart

Your memory is this day.

As the ivy clings to the tree,

So my memory clings to thee.

– Inserted by her loving husband –

<<<<<>>>>>

France, 1916

Bmdr. Timpson had rejoined No.5 Battery in mid May and four weeks later, on 17 June he sustained a severe gun shot wound (GSW) to his left hand. Initially treated on the spot by 2 NZ Field Ambulance, he was evacuated the same day to No.1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station at Adinkerke in Belgium which fortunately had just arrived from their former location at Aubigny, but not yet fully established. The severity of his wound was confirmed and necessitated Bmdr. Timpson’s evacuation to England. Adinkerk is about 20 km north of Dunkirk and Bmdr. Timpson was scheduled to travel on the Hospital Ship New Haven from the southern port Le Havre. This meant an at times dangerous 350 km road and rail journey down coastal France through Dunkirk, Calais and Dieppe to the port. At any time the transports could be randomly bombed by German aircraft as the Base Camp at Etaples and some of the Hospitals therein would find out in May 1918.

LYTTELTON TIMES.

VOLUME CXVII, ISSUE 17213,– 6th, JULY 1916

PERSONAL NOTES.

Bombardier J. T. Timpson, wounded on June 17, is the youngest son of the late Henry Timpson, of Mount Somers. He served in the South African war and returned to New Zealand when peace was declared. He left with the 8th Reinforcements. Bombardier Timpson has four nephews serving, three at the front and one in Trentham. Bombardier Timpson is a nephew of Mr W. Wheelband, of Wilson’s Road, Linwood. He is a widower with five children.

<<<<<<<<>>>>>>>>

Prior to leaving Gallipoli, Bmdr. Timpson and Gnr. Clinton Baddeley, both Coasters, responded to gifts of tobacco sent to the West Coast men overseas from Hokitika, by one of the many soldier’s welfare groups that proliferated in every town who had men go to war. Jack and Clint’s letters of response were published in the local newspaper:

WEST COAST TIMES.

THE SOLDIERS’ AND SAILORS’ TOBACCO FUND.

29th, NOVEMBER, 1915:

WESTLAND SHILLING LISTS: – PRESENT MONTH FOR WEST COAST SOLDIERS.

Street collections, Ross (per T. W. Bruce), Town Hall list, Gift Depot list, -: Totals:£258. 4s. 3½d.

The last mail brought numerous acknowledgements from Gallipoli and France where smoke comforts from money supplied from Westland had been distributed. One battery, under Major Falla, included several Coasters, and cards came from the men indicted at Anzac Cove, dated 29th September. The gifts were highly appreciated, and Gunners Timpson and Badeley write in very cordial terms acknowledging the gifts. There will not be any street collection in Hokitika this month. Instead there is to be a novelty concert in the Princess Theatre on Tuesday night. Admission will be free, and the performers will be drawn from the audience. The local orchestra is assisting, as also several well-known performers. A collection will be taken up in aid of the fund. Mr. T. W. Bruce will preside.

Dardanelles, 27th September.

“Dear Friend. —Your kind gift received, and many thanks from 5th Battery, N.Z.F.A. The boys are doing fine and Johnny Turk finds them a hard nut to crack”, Yours truly.— J. T. Timpson.

Gallipoli, 27/0/15.

“Thank you very much for the tobacco. By strange coincidence it was received by an ex-Hokitika boy, namely—Gunner Clinton Baddeley, N.Z.E.F., son of Baddeley of the Bank of New Zealand. I have met several West Coasters here among them A. Dowell. We are still pegging along slowly.” Kind regards to everybody.— C. Baddeley.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On arrival in England, Bmdr. Timpson was admitted to the Spalding Military Hospital at Hendon in north London. With his left hand patched up, he was then sent for a period of convalescence to “Grey Towers”, the NZ Convalescent Hospital, on 7 June pending his return to the front in France.

By 16 August, Bmdr. Timpson was back in the field with the NZFA and assigned to a 2.0 inch Medium Trench Mortar Battery. His hand wound had caused some loss of function and as a result he was transferred to a slightly less physical role than shifting artillery pieces or mortars by hand – he was transferred to the NZ DAC – the Divisional Ammunition Column whose job it was for loading, delivering and unloading ammunition to the batteries of field guns and trench mortars in the unit, an equally dangerous job and particularly vulnerable to random enemy artillery or air attacks. In this role, Bmdr. Timpson was employed as a Section Commander of a team of Gunners who were responsible for the preparation and delivery of ammunition to the Brigade’s gun batteries (light and heavy artillery guns), and the Medium and Heavy Trench Mortar batteries. He also managed a number of ammunition wagon drivers as well as pitching in to be a ‘lifter & shifter of ammo stocks when required. This was heavy work and often dangerous, not only from preparing ammunition but also transporting it over all types of terrain (mostly through mud), sometimes under fire.

In Oct 1916 his evacuation for Bmdr. Timpson was again necessary, to England for an unspecified infection. Within days of his release and anticipated return to France in November, Bmdr. Timpson went down with Pleurisy and admitted to No.3 NZ General Hospital at Codford.

Jack managed to see Christmas 1916 through in England however by March 1917, he was again back in France at the front. In June, and still with the DAC, he was posted to ‘Z’ – Medium Trench Mortar Battery. In late August, Bmdr. Timpson suffered an accidental back injury (lifting?) which was compounded by acute Myalgia. Muscle pain is a primary symptom of Myalgia, the common cause being overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; acute Myalgia may also be due to a traumatic history — hardly surprising for a battlefield participant who survived the First Battle of the Somme, of Passchendaele and Messines! Evacuation to one of the British Stationary Hospitals in Boulogne was ordered. Both the General and Stationary hospitals where possible, were set up in large seaside hotels or some of the bigger and rather opulent mansions on private estates, their surroundings being most conducive to aiding recovery. Once admitted to one of these ‘oases in the desert’ soldiers were in no great hurry to return to the front. Recovery for Bmdr. Timpson was steady however while convalescing, the Myalgia returned to the extent that in December, he was re-admitted this time to No.3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill).** This hospital was renowned for the expertise of its specialist physicians on staff, particularly in diagnosing and treating the more obscure complaints such as Myalgia.

Note: ** During the Great War, McGill University fielded a full general hospital to care for the wounded and sick among the Allied forces fighting in France and Belgium. The unit was designated No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill) and included some of the best medical minds in Canada. Because the unit had a relationship with Sir William Osler, who was a professor at McGill from 1874 to 1885, the unit received special attention throughout the war. The unit cared for thousands of victims of the war, and its trauma care advanced through the clinical innovation and research demanded by the nature of its work. By the war’s end the McGill hospital was known as one of the best medical units within the armies in France.

Source: PMC – US National Library of Medicine & National Institutes of Health

Specialist diagnosis directed his evacuation again to England via the HS St. Denis and admission to the City of London Military Hospital for further treatment. After two weeks, Bmdr. Timpson was released to No.2 NZ General Hospital at Walton-on Thames in March 1918. By June, Bmdr. Timpson was transferred to “Grey Towers’, the NZ Convalescent Hospital at Hornchurch where he underwent a Medical Board’s assessment of his fitness for continued service.