~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

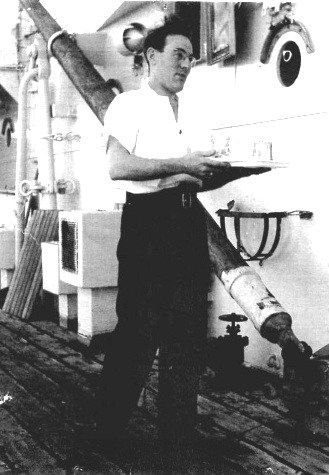

Senior Sergeant Benton “Benny” Ostler is a senior serving New Zealand Police Officer who, after leaving Wellington College in 1982, enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Navy as a Radio Operator. He served on various ships, predominantly on the old Leander-class frigate HMNZS Canterbury. After leaving the RNZN in 1988, Benny’s plan had been to join the police force however this aspiration was put on hold while he recovered from a serious knee injury he had incurred playing rugby. In the interim, Benny secured work as a Prison Officer at the old Mt Eden Prison long enough for the injury to heal, and subsequently pass the physical requirements to join the NZ Police.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Benny’s quest

In October 2022 I received an email from Benny regarding one James Robertson Mackay who died in Wellington sometime during the 2000s. James was a Scotsman who had been a career naval rating. He joined the Royal Navy (RN) during World War 2 and later transferred to the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) in the early 1950s.

Benny’s only knowledge of James Mackay stemmed from his childhood during the 1970s when James had lived with the Ostler family in Wellington. During that time James became Benny’s ‘Godfather’. When Benny was advised by family James had died in a Wellington rest home, having not seen him since the 1990s, Benny realised just how little he actually knew about his godfather. Even Benny’s father who had briefly served with James in the RNZN and been a good friend, was unable to shed any additional light on either James’s origins or his service. Curious to know more, Benny as a serving police officer was limited in what he could lawfully access for his private use through police channels and so relied on what he could find on the internet. Despite his best efforts he found very little. Without James Mackay’s date and place of birth, the location of his death or even a grave from which to derive some basics, his godfather became even more of a mystery. Benny had essentially hit the wall for information about his godfather and so resorted to asking MRNZ for help.

Whilst I could definitely assist with some of Benny’s queries relating to the genealogical aspects of James Mackay’s life, historical records of his navy service that were not available on-line would have to come from navy. There was also the question of medals. Presumably James had been entitled to some as he had been in the navy during World War 2. I suggested to Benny that potentially there could be other medals, perhaps unclaimed, as several NZ medals that recognised retrospective operational service had been instituted after James’s death? Whether or not Benny’s relationship as ‘godson’ could make a claim if there were any, was also a question mark?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Uncle Mac”

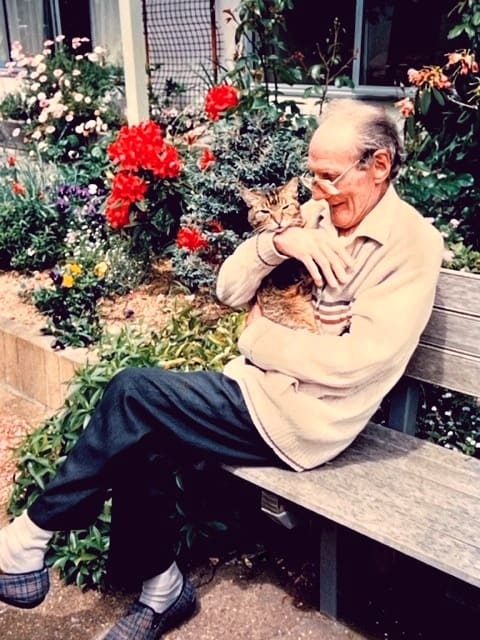

Benny briefed me on James Mackay’s background as he knew it, how Mac had become involved with the his family, and how this had led to “Uncle Mac”, as the Ostlers knew him, becoming Benny’s godfather.

James Robertson Mackay was a Scotsman of unknown parentage who served in the Royal Navy as a Steward during WW2. Sometime after the war Mac had joined the RNZN, again as a Steward. He had arrived in New Zealand alone and without connections other than those he arrived with. As a consequence, when Mac arrived at HMNZS Philomel in Auckland he was befriended by NZ14660 LSIG David Lincoln Ostler, a Signalman (aka ‘bunting tosser’) and Benny’s father. David Ostler left the navy a few years later while Mac had remained for about ten years, roughly completing 18–20 years in both navies before being medically discharged around 1960ish. Mac apparent had also been known for having a legendary capacity for alcohol (where have we heard this about servicemen before, sailors in particular?). After Mac left the navy, a series of incidents resulted in his falling on hard times. It was then that David Ostler’s historical friendship forged between he and Mac during their navy service, led David to offer Mac a place to stay with his family in Wellington, a stay which had extended to several years.

While living with the Ostlers, Uncle Mac had bonded with Benny and his siblings. In due course David Ostler had asked his old colleague if he would be Benny’s godfather – Mac enthusiastically accepted. After the children started high school, Mac left the Ostlers however within a couple of years he returned. Repeated efforts by David to get Mac into stable employment led to friction between the two and their friendship soured. This resulted in Mac leaving the Ostlers for good to live in the city. Benny had naturally been concerned when his godfather left, unaware of what had caused the rift between his dad and Mac. Being Mac’s godson, Benny maintained contact with Mac by visiting him whenever he could. Contact between the two however tapered off once Benny joined the navy and later began his Police career. Contact between Benny and Mac virtually ceased after Benny was posted away from Wellington. Since that time, Benny lost visibility of Mac’s whereabouts and Mac appeared to vanish from the Ostler’s lives altogether. That was until Benny was advised of Mac’s death which started him on a quest to find out more about his ‘Uncle Mac’.

Apart from wanting to know more of his godfather’s origins and naval service, Benny was also interested to find out what had happened to Mac’s medals. Benny correctly surmised Mac must have had medals from his WW2 service however could never recall Mac ever wearing any. Benny was keen to replicate medals Mac had qualified for as a memento of his godfather and with which he could honour him on Anzac Days. I also reminded Benny that Mac potentially may have qualified for New Zealand medals as several had been instituted long after he was discharge from the Navy – another of the many questions that needed answers.

Where to start ?

Experience has taught me that a large number of medals that are either reported missing or suspected of being lost or stolen, are often found in the hands of another family member, a distant relative or even a neighbour of the deceased veteran. Sorting out the circumstances of what occurred at the time of the veteran’s death is a critical start point. Relatives who have medals sometimes receive them unexpectedly and generally don’t have a clue what to do with them. The medals get sidelined, nobody asks after them and so a family is none the wiser, the owner eventually forgetting about them altogether. This can go on for years with medals changing hands after the owner’s death, being either gifted, inherited or found before they are accidentally thrown away! I advise all persons contacting MRNZ who think their family medals are missing to first ask the question of all the most likely family members who had contact with the medals, before embarking on a path of replacement – very often they will turn up with a person you least suspect of having them. Such was the outcome of this case.

While Benny checked with his own families for any evidence of Mac Mackay having medals, my internet search for details of the life of James McKay (also spelt MacKay, McKay and Mackay in some of the public records) started with his death in Wellington and progressed back to Scotland. Mac’s name proved to be problematic from the outset. Not only were there variations in the spelling of his surname but there was very little official information about him. Mac’s apparent lack of a family and identifiable addresses in Scotland added to the difficulties in determining who the correct individual was.

Finding out the details of Mac’s Royal Navy service was also problematic. The records of naval ratings who had enlisted after 1920 are only viewable either at the UK National Archives Kew, or they could be requested in hard copy, a process by Archives own admission can take anywhere up to a year to process – and it’s expensive!

Access to Mac’s RNZN service record would be much easier and hopefully contain details of his prior service in the Royal Navy. My primary ‘port of call’ for such information is a most helpful retired senior RNZN officer, Lt-Cdr Rick whose expertise I value greatly. Rick is a part-time staff member of the NZDF Personnel Archives and Medals (PAM) section. A former colleague and veritable mine of information of the RNZN and naval service generally, Rick is also an expert on navy medal entitlements. I could see from the limited information Benny provided me that barring any disciplinary issues which might remove a medal entitlement, there were at least three NZ service medals Mac may have been entitled to after his service concluded. Whether or not Benny would be permitted to claim these in his capacity as a godson was a determination that Rick would be able resolve.

Author’s Note The discovery of some of James Mackay’s personal effects towards the end of this case produced a trove of paper records which included his Royal Navy Certificate of Service and a Birth Certificate. From these I was able to obtain additional personal and career details not contained on Mackay’s RNZN record. While much of this information was not known until the end of the research, the remainder of this story has been written as if these details were known in order to present the detail of James Mackay’s life and naval career in a cohesive sequence.

Scottish heritage

“Scotland’s People” is a website that contains registered births, marriages and deaths in Scotland. In consulting this source I found the birth records of two persons named “James Robertson Mackay” registered at Edinburgh. James’s navy records showed he had been born in Edinburgh in 1920, the two website records however recoding only the year of registration – 1922. One child was born at George Square and the other at South Leith. Both of these places fall within the Edinburgh district boundary, George Square in the central city of Edinburgh, and South Leith being part of the Edinburgh port town of Leith situated on the east coast (officially in Midlothian) – the latter birth at South Leith seemed the most likely.

Further cross checking revealed Mac’s father to be James George MACKAY (1899-1963) who was born at Leith, a ship’s cook and later a steward in the mercantile marine service. George Mackay married Margaret ROBERTSON, also from Leith, on 3 Aug 1920, just six days prior to the birth of their son James Robertson Mackay on 9 August 1920 at the Royal Maternity Hospital, Edinburgh. George Mackay’s itinerant sea-going occupation no doubt accounts for the lack of residential address entries in both the local electoral rolls and Scottish census.

Young James Mackay, an Edinburgh shop assistant left South Leith in September 1942 to join the Royal Navy. He was still serving when his mother Margaret died at Leith in 1948. His father George re-married Jessie COCKBURN and together they had a son, James’s step-brother believed to have been named Kenneth Mackay. For all intents and purposes, when James left home it was for good. Whether or not he ever returned to Edinburgh or Leith is unknown, possibly during the war when he was in the area from time to time, but otherwise there is no evidence to suggest he ever made contact with his father, step-mother or step-brother.

To what extent, if any, James Mackay’s career choice of Steward in the Royal Navy had been the result any of his father’s influence while growing, again can only be speculated upon. Whatever the case, it is well known globally that any sea-going occupation, particularly those of cook and steward, are renowned for their association with alcohol which was not only nearly always easily accessed and cheap, but its consumption actively encouraged. This way of life undoubtedly shaped James Mackay’s young life and his service in the navy. The very nature of a seaman’s life and the social indulgences to which they are routinely exposed when travelling the world, has created and will continue to create men and women of James Mackay’s ilk in every sea-going occupation, military and civil, on the planet.

A life on the ocean wave …

LX 31779 J. R. McKAY, ASTD (Able Steward) – Royal Navy

James Robertson Mackay worked as a Shop Assistant prior to enlisting with the Royal Navy on 13 April 1942, seven days before his 20th birthday. At only 5’ 3¼” (161 cms) tall, he was a small young man who began his career at HMS Glendower, a WW2 naval camp located on the Pen-y-chain peninsula near the Welsh town of Pwllheli. After the war this camp became one of the well known Billy Butlin’s holiday camps. At HMS Glendower James learned the basics of naval life before he began training in his chosen trade of Steward.

As James had enlisted mid-way through World War 2, there was little time for formalised trade training in the non-specialist trades so learning the requirements of trades such as Steward was done on-the-job, in real time. Stewards were employed predominantly on shore bases however were also required at sea to look after both officers and crew on all manner of ships. Mobilisation of the Royal Navy meant that there were many more opportunities to be posted to sea, to locations world-wide for most non-technical trades. The majority of James Mackay’s initial postings were to ‘stone frigates’ (shore bases, e. g. HMS Vivid) however a posting to sea came before the war ended.

First posting

From HMS Europa, Assistant Steward Mackay was posted HMS Flora, the Royal Naval Dockyard at Invergordon, until Nov 1942. Invergordon is a port town at Easter Ross in the Firth of Cromarty Firth, Ross and Cromarty, Highland. Flora was a ‘secret’ base that supported coastal force vessels including minesweepers, harbour defence craft, auxiliaries and the occasional destroyer.

Scapa Flow, Orkney

The now qualified Able Steward (ASTD) James Mackay was posted to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands where he served in several locations. A body of water in the Orkneys that is sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy, Scapa Flow was again selected as the home base of the Royal Navy’s fleet during WW2, as it had been for the Grand Fleet in World War 1, mainly because of its great distance from Germany and therefore apparent secure anchorage. It was however penetrated by German submarines during the World War 2, at great cost to several RN ships.

A number of floating (ships) and shore based naval establishments had been established in the Orkneys, some of which ASTD Mackay served for varying periods of time from a few weeks to many months. His more significant postings were:

-

Kirkwall Hotel, Orkney.

HMS Pyramus – A minesweeper and anti-submarine base, the headquarters being situated in the Kirkwall Hotel on the mainland of Orkney which was ASTD Mackay’s first stewarding job in the Orkneys. - HMS Dunluce Castle – In Feb 1943 he served on the HMS Dunluce Castle, a submarine depot ship** based at Scapa Flow. In 1939 the Dunluce Castle had been sold for breaking up but was rescued by the Admiralty and requisitioned for use. The Castle was largely static however could put to sea if required. It was tasked with a variety of roles; stores for the small ships of the Royal Naval Patrol Service, temporary accommodation for crews awaiting their next draft, mail sorting ship for the Home Fleet, submarine tender and a respite for survivors from the Arctic Convoys.

Note: ** A depot ship is an auxiliary ship used as a mobile or fixed base to provide services unavailable from local naval base shore facilities for vessels with limited space such as submarines, destroyers, minesweepers, fast attack craft, landing craft or other small ships. Depot ships provide space to carry spares and carry out maintenance/repair tasks, as well as crew dining, accommodation and recreation facilities.

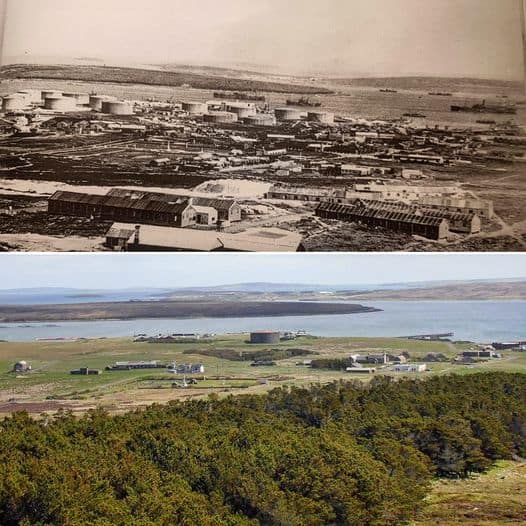

- HMS Porsperine (Sycamore) – ASTD Mackay spent 10 months posted to HMS Porsperine. Situated at Lyness on the east coast of the island of Hoy, Orkney, it had briefly been the headquarters of the metal salvage firm of Cox and Danks’s who were raising the German High Seas Fleet which had been scuttled by the Germans in June 1919, during the Armistice. Porsperine was the main base during WW2 for naval personnel posted to the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow. In Sept 1939, the services available at Lyness gave the Royal Navy repair, refueling and resupply facilities.

- Known also as Lyness Naval Base, HMS Porsperine (nick-named ‘Proper Swine’ by those posted there) was home to thousands of navy and military personnel during WW2. Some loved it and others loathed the place but for most it was an unforgettable experience. Lyness was also vital for giving sailors respite from ship life by providing recreational facilities and accommodation (such as a depot ship provides on a smaller scale when afloat), with the base reaching a peak of 12,000 servicemen and women in 1940. By 1940 over 12,000 military and civilian personnel were stationed at Lyness to support the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow.

West Africa

- HMS Eland – From the Orkneys, it was back to HMS Europa for ASTD Mackay and a period of training in preparation for his first posting overseas in May 1944. HMS Eland was a newly built Royal Navy Dockyard and shore base in Sierra Leone, constructed up river from the capital of Freetown, as part of the expansion of naval facilities at Freetown during World War 2. Eland was adjacent to the area known as Kissy.

Home Fleet (Scapa Flow)

- HMS Paris (Essendon) – Returning to mainland Scotland in Oct 1944, ASTD Mackay served again at HMS Europa including a tour of duty to HMS Paris (Lord Essendon), a ship docked at Plymouth in the south of England. On 3 July 1940, as part of Operation “Catapult”, British forces forcibly boarded this French ship to press her into use for war service. She was used as a depot ship and as a barracks ship by the Polish Navy for the rest of the war. On 21 August 1945, after the war had ended, Paris was towed to Brest and returned to the French where she continued in her role as a depot ship.

- HMS Paragon – A minesweepers shore base at Hartlepool, a seaside and port town in County Durham.

- HMS Lochinvar – ASTD Mackay returned to HMS Europa in June 1945 for six months before being posted to HMS Lochinvar in Jan 1946 until Feb 1948. Lochinvar was a ‘stone frigate’ that became an active minesweeper training base in 1943, situated at Granton. Sited at Port Edgar on the Firth of Forth, Granton forms part of Edinburgh’s waterfront along the Firth of Forth and is, historically, an industrial area having a large harbour.

‘Old Blighty’

The next four years of ASTD Mackay’s service was largely spent in the south of England’s around the two major naval bases Portsmouth and Plymouth. Ship’s that feature on his service record with names such as HMS Pembroke, Pembroke II, Chatham, Drake, Condray were all ‘stone frigates’, administrative bases and accommodation locations that managed or accommodated vast numbers of naval men employed at the naval dockyards building or repairing ships, or attending training schools.

- HMS Fulmar – A brief posting in April 1949 to HMS Fulmar was a unique posting for James Mackay. Fulmar was an airfield opened by the RAF for Bomber Command. Transferred to the Fleet Air Arm (the Navy’s flying arm) in 1946, it became the Royal Naval Air Station Lossiemouth, or HMS Fulmar.

- HMS Woolwich – In May 1949, ASTD Mackay’s service was extended to accommodate a sea posting to the Mediterranean Fleet aboard HMS Woolwich, a destroyer depot ship, a floating maintenance and repair ship. She had been stationed in the Med since 1936 and 1939 as a depot ship and destroyer tender built for the Royal Navy during the 1930s. The ship was initially deployed to support destroyers of the Mediterranean Fleet. During World War 2, she was assigned to the Home, Mediterranean and Eastern Fleets. She briefly returned home in 1946, but rejoined the Mediterranean Fleet the following year with Able Steward Mackay aboard. HMS Woolwich was permanently returned to the United Kingdom in 1948 and became a maintenance and accommodation ship.

Discharge & transfer to RNZN

The Royal New Zealand Navy was established as navy in its own right on 1st October 1941, previous contributions of NZ sailors being made to the Royal Navy’s New Zealand Division in the UK. Populating this relatively new service post-war was difficult when taking into account battle losses of New Zealand sailors together with the numbers who exited the navy after the war. Interest in the military understandably had all but dried up and recruiting suffered. New Zealand looked to the United Kingdom as a source of experienced personnel across all three services who were actively recruited with attractive transfer contracts.

When ASTD Mackay returned to England, final postings to various shore establishments at Portsmouth and Chatham saw him through to the expiration of his RN service extension in August 1952. By this time Mac had made application, and been accepted, to transfer to the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN). His record in the RN, whilst not outstanding, was acceptable for RNZN service in the same trade of Steward. Having ten years Royal Navy and war service, both at sea and ashore throughout his 38 postings, his worth as an experienced Steward had been well established. Mac’s apparent lack of promotion was not considered unusual since many senior sailors of this time preferred to serve without rank for their entire career so Mac’s lack of progress was not of concern.

Defence Medal, War Medal 1939/45

Other: Good Conduct Badges – 1st (1945), 2nd (1950)

RN Service: July 19 1942–August 1952 = 10 years 1 month

NZ 13894 J. R. MACKAY, ASTD – Royal New Zealand Navy

Mac was officially transferred to the Royal New Zealand Navy on 15 August 1952 as an Able Steward. Thirty years of age and single, Mac left Glasgow on the TSS Captain Cook, the ship that within a few short years would be transporting the New Zealand soldiers to a hot spot in South East Asia – Malaya. His was one of three drafts of former UK navy and air force personnel that transferred to the NZ Military Forces during the early 1950s. In addition to a draft of ex-RAF personnel on Mac’s voyage, he was one of 30 ex-Royal Navy sailors from England, Wales, Scotland, Canada and India.

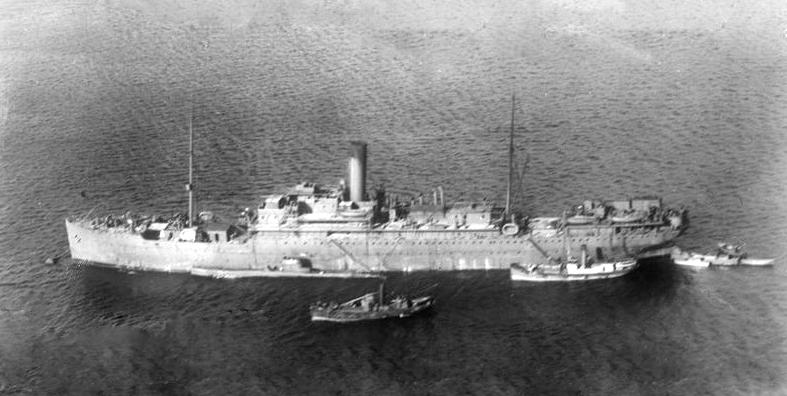

Arriving at Wellington, Mac spent his first four days in NZ aboard HMNZS Maori on its delivery voyage to Auckland from Wellington. Maori was a Fairmile B Motor Launch that had just be re-purchased by the RNZN from a private buyer. Mac checked into HMS Philomel, a New Zealand ‘stone frigate’ and home of the RNZN at Devonport Naval Base, Auckland.

For the remaining four months of 1952, Mac was posted to the naval training station HMNZS Tamaki on Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf. Here he underwent basic training in order to come to grips with the RNZN’s practices and procedures. In January 1953, ASTD Mackay’s first RNZN sea posting was to the crew of HMS Kaniere where he was appointed Captain’s Steward for the next 18 months until May 1954.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Korean War, 1950-1954

HMNZS Kaniere F426 was being prepared for operational service as she had been nominated for detached service with the 11th Frigate Squadron as part of the UN Naval Task Group based at the port of Sasebo in Japan. On 3 March 1953, Kaniere departed Auckland for her Korea deployment station to relieve her sister ship HMNZS Rotoiti that had completed two deployments to Korea. Kaniere arrived at Sasebo on 23 April 1953, departing the next day to carry out her first patrol of the west coast of Korea. HMNZS Hawea was also deployed there at this time.

With a cease-fire being imminent in early 1953, HMNZS Kaniere was re-deployed to evacuate South Korean partisans from the outlying islands above the 38th Parallel which had been proposed as the Armistice demarcation line, separating the UN forces in the South Korea and the North Korean/Chinese forces.

During May 1953, Kaniere carried out patrols and provided naval gunfire support. The fire support included providing cover for a minesweeping operation and the evacuation of wounded South Korea guerrillas from Chodo Island off the west coast. Later in the month Kaniere provided support to a USN vessel in the Regency Channel and came under fire from North Korean shore batteries. She returned to Sasebo unscathed and then proceeded to Hong Kong to join HMNZS Hawea. At this time both ships took part in Commonwealth celebrations and were inspected by the Commander in Chief, British Forces in Korea.

All of the Loch-class frigates had a hard and monotonous role in Korean waters. There were no naval battles per se or the defending of UN convoys against enemy attack, but denying the sea to the North Korean and Chinese forces while making use of the naval supremacy of the UN forces was essential work for the New Zealand frigates.

-

HMNZS Irirangi 1954/55 – On his return to Auckland, ASTD Mackay went from the tropical SE Asian frying pan into the fire with the posting of every service person’s dreams – Waiouru in winter! Mac was posted to the support staff at HMNZS Irirangi on 13 Apr 1954 for approximately 18 months. Irirangi was a ‘stone ship’, a shore based facility for the super-secure military communications which was remotely located south of the Waiouru Military Camp. Irirangi was staffed with around 30-odd military and civilian personnel working 24/7 on rotational shift work. Mac’s posting to Irirangi also coincided with his qualification for a 3rd Good Conduct Badge which cleared the way for the award of the Naval Long Service and Good Conduct Medal, provided he performed satisfactorily for the next three years.

- HMNZS Bellona 1955 – In Sep 1955, ASTD Mackay was again posted to sea as part of the crew who left Auckland to return the old Improved Dido-class cruiser HMNZS Bellona to the Royal Navy that had been on loan to the RNZN. While in England, the crew were required to parade for the commissioning ceremony of HMNZS Royalist, Bellona’s RNZN replacement. The Naval Board was keen to ensure that as many young naval ratings as possible were given the opportunity to participate in this commission, and the idiosyncrasies of the English language resulted in one of the more memorable messages in New Zealand naval history: ‘Ratings drafted to Bellona for passage to UK should be vice trained men’. HMNZS Bellona arrived at Portsmouth on 12 December, its ship’s company transferring to the refitted Royalist ready for her commissioning into the RNZN.

- HMNZS Royalist 1956 – Also a Dido-class light cruiser, one of three of her class loaned to the RNZN, the other being HMNZS Black Prince. All three spent periods on loan at various times with the Royal New Zealand Navy. After Royalist departed Plymouth on 15 July 1956, she was re-deployed mid-voyage at the request of the British Government to join the Royal Navy’s Far Eastern (Mediterranean) Fleet to assist in sea exercises off Malta. Her superior re-fitted communications systems would be valuable assisting with the provision of early warning for RAF fighter aircraft that were returning from operations, to their bases in Egypt, Cyprus and Aden. On 30 October, the Fleet was still exercising when Royalist was brought to full preparedness for war as the Suez Crisis escalated. As the operations began, Royalist was suddenly ordered to detach and withdraw as the New Zealand Government had refused to let the cruiser participate in the action, somewhat to the frustration of the ship’s company. HMNZS Royalist returned to Devonport on 23 July 1956.

Back on terra firma and posted to a shore-based stewarding appointment at HMNZS Philomel, ASTD Mackay received his Long Service & Good Conduct Medal one year later on 13 April 1957. At this point in his navy career, Mac’s combined naval service in both the RN and RNZN was approaching 16 years. With his service contract due to expire in February 1959, Mac would only have completed a combined total of 17 years service in both navies which was still three years shy of the 20 year qualifying mark to be eligible for a military pension. ASTD Mackay (35) applied for an extension but was denied. The writing was on the wall – the denial of Mac’s application cost him dearly, however as I learned, this had been a outcome of his own making.

Discharge on the horizon

Mac had “issues”…. long standing issues that related to his alcohol consumption which had been a hall mark of both his RN and RNZN service. Mac’s service records made mention of this at every posting except for those to HMNZS Bellona and Royalist. Perhaps he was under “orders” re his drinking and the pressure was on when the crew had gone to England. This may have accounted for his service record noting that he was “a far better Steward than his previous records indicate”.

Navy rum, or Squirt** as it was known in the RNZN, was undiluted rum that had an alcoholic percentage of 98%, or 148 over-proof. While the rum was diluted for junior sailors who were required to consume their ration within 20 minutes while under the supervision of a duty officer, senior rates were issued theirs neat and could consume it at their leisure. This frequently led to rum being cached for subsequent use at parties or sessions ashore. The RNZN was the last Navy in the world to end this tradition in 1990.

The denial of an extension to his service to complete 20 years and his looming discharge from the RNZN should have come as no surprise to Mac. By not heeding the Senior Medical Officer’s advice re his drinking and lifestyle, AS Mackay had reached the stage of no longer being able to meet the physical standards required by the Navy, ergo, he was no longer able to be deployed overseas which was a significant limitation to a sailor’s use. Bitterly resigned to the fact, he began taking the accumulated and long service leave owed to him which had to be expended before his discharge was to take effect in March 1959.

Mrs “Mac”

In August 1958, with the end of his career just a few short months away, Mac embarked upon a path many would have said would never happen – he got married!

When Mac emigrated to New Zealand on the TSS Captain Cook back in 1952, also on board was a Miss Elizabeth Beldam. The passenger manifest listed Elizabeth as an unmarried woman, 38 years of age whose occupation was “Canteen Assistant”. Elizabeth “Sissie” Beldam was born at Maidenhead in Berkshire on 1st Jan 1914 to parents Henry BELDAM (1881-1963), a Marine Dealer (ship’s chandler) and Rosina Ellen LEE (1882-1938) whose parents were an itinerant Gypsie (‘traveler’) family. Elizabeth She was the fourth child of eleven, seven girls and four boys, not all of whom survived childbirth. The Beldam family had a long history in Berkshire since the mid 1770s. Henry Beldam was originally from Hackney in London and had been taken to Skimped Hill, Brackwell as an infant, remaining in the family’s house all of his life.

At the time Mac joined the Royal Navy in 1942, Elizabeth Beldam (28) joined the Women’s Land Army as a Cook however medical issues forced her to resign in March 1943. Thereafter she gained work as a canteen worker serving food, tea, alcohol and dried goods in the land Army’s establishments. Deciding to emigrate to NZ in 1952, Elizabeth left her three un-wed sisters Sally (b1909), Ellen (b1916), and Mabel (b1919) and father (mother Rosina had died in 1938) in their family home in Skimpers Hill Lane, Brackwell.

Following her arrival in Wellington in Sep 1952, Elizabeth remained in the city for her first few years in NZ and engaged in various live-in hospitality and domestic work positions. In January 1955, she travelled back to England via Sydney aboard the SS “Otranto”, presumably her last trip home to her Skimped Hill family. She stayed with her father for a little over a year, the last time she would see her father and sisters, she returned to Wellington on the SS Southern Cross in June 1956.

On returning to NZ, Elizabeth landed a position as a Housemaid at King’s College in Auckland and was still in their employ when she and Mac (38) married at the Auckland Registry Office in August 1958. Whether or not they had known each other prior to immigrating, or perhaps planned to marry for mutual convenience subsequently, is unknown but certainly the coincidence of their travel and eventual marriage was uncanny.

Discharged

Mac’s last day at work in the RNZN was the February 5th, 1959. The reason for his discharge was stated on his papers: “Below Naval Physical Standards”. In spite of advice to the contrary, Mac’s discharge from the navy was a reflection of his unwillingness to modify his drinking habits.

RNZN Service: August 1952–March 1959 = 6 years 6 months

Medals: Korea Medal, United Nations Korea Service Medal (Korea), Naval Long Service & Good Conduct Medal, Apr 1957 = 15 years satisfactory service required

Total RN and RNZN service: 16 years 7 months + war service additional = 17 years (+/-)

Other: 3rd Good Conduct Badge (1954)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Life after the Navy

The Mackay’s moved into 231 Remuera Road, Mt Hobson temporarily before settling into 125 Ladies Mile, Remuera a few months later as Mac completed his discharge administration to leave the Navy. It is sad to say that in the first few years of his marriage, Mac probably had good cause to imbibe after learning his wife Elizabeth had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The recent loss of his first job as a Clerk had also necessitated their move to a small flat at 24 Gavin Street in Ellerslie. It was here that Elizabeth (Beldam) Mackay died on 17 February 1967, at the age of 53. There were no children from their union.

A friendly port in the storm …

When David Ostler learned of the death of his former shipmate’s wife Elizabeth and his stint in Mt Eden Prison, he reached out to offer help. When Mac was released at the end of 1967, David and his wife Sianaua extended the hand of friendship and offered Mac a place in their family home at 53 Central Terrace in Kelburn, Wellington. Mac was welcomed in and soon became a favourite with the children who dubbed him “Uncle Mac”. Mac’s initial stay with the Ostlers extended to a couple of years before he returned to Auckland to try and re-start his life. Unfortunately his desperation for alcohol again landed him in trouble. In 1973 his theft of alcohol netted him 18 months in Mt Eden.

Upon Mac’s release in 1975, his compassionate mate David stood by him yet again, offering him lodgings with the family who by then had moved to 26 Lynmouth Avenue in Karori. It was during this second period with the Ostlers that Mac agreed to become teenager Benny’s ‘godfather’. David had also helped to get Mac back into work. Jobs as an Office Assistant and then as a Public Servant, unfortunately were short lived – Mac had been let go from both for his ‘issues’. A job in which the serving of alcohol was integral was hardly the type of work that would keep Mac out of trouble but, against the odds, Mac got himself a Steward’s position at a Wellington Gentleman’s Club. After three months he was dismissed for stealing alcohol.

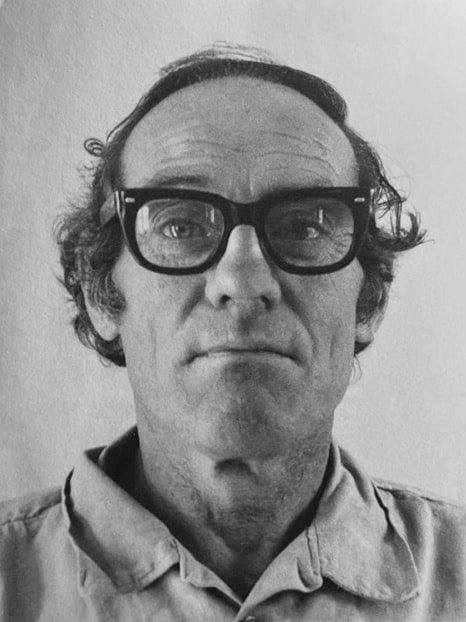

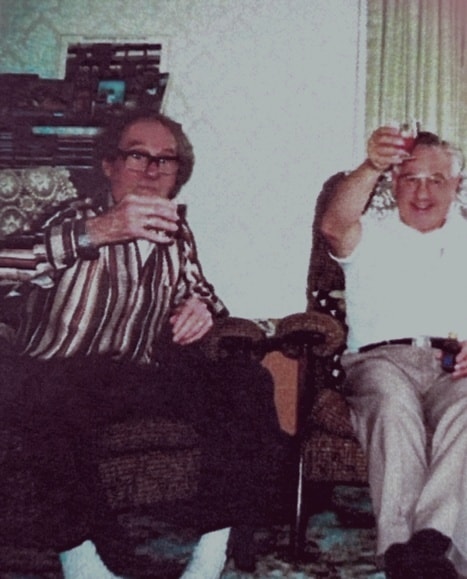

David Ostler had tried numerous ways to help his old colleague but seemingly without any lasting success, Mac and alcohol invariably being the problem. Mac was an intelligent man but unfortunately had been in the grip of the ‘demon’ for so many years, he knew no other way. Eventually this bought about a day of reckoning between David and Mac. In 1985, their acrimonious parting resulted in the friendship of the two men being extinguished for good. Mac left the Ostlers and moved into the Rolleston Street Flats in the Wellington city suburb of Mt Cook. Once he had gone, David understandably had little more to do with him. It was indeed a sad end to what had once been a mutually enjoyable relationship between Mac and the Ostlers. In 1997, David and Sianaua moved to Auckland. Ironically in spite of what had transpired between David and Mac all those years ago, David now 87, still displays a photograph in his home of he and Mac in each others company during much happier times.

Gone but not forgotten

Sorry to see his godfather go, Benny had initially made the effort to keep in touch with Mac by visiting him whenever he could although Mac’s mental decline began to manifest in him as Paranoia. The opportunities for Benny to visit his godfather also became less frequent once he finished high school and began his working career. On the occasions when Benny or his siblings could visit Mac, he become suspicious of them, believing they were passing information about him to their father. He then refused to see anyone, even his once favoured ‘godson’ Benny. Mac’s declining faculties and paranoia were no doubt attributable to years of over indulgence as well as his advancing years.

Epilogue

James Robertson MacKay was very much a product of his time. His haphazard upbringing in Edinburgh, growing up in the port towns of Leith and Glasgow and whose father was often at sea as a cook or steward with the mercantile marine service, seemed to pre-determine a career path for Mac at sea. A life at sea, be it the mercantile marine service or navy is a well worn path where young sailors not only find that alcohol is readily available and cheap, but its consumption actively encouraged. This undoubtedly influenced Mac’s early life and shaped him when he joined the Royal Navy. The very nature of a seaman’s life and the social indulgences they are routinely exposed to has created thousands of “Macs” over the years in both the civil and military seafaring world (and every other armed force of the world). Fortunately times have changed considerably. The navy (and armed services generally) are now well disposed to the supervision of alcohol consumption and their duty of care for the men and women therein.

Mac’s history of heavy drinking and smoking together with ageing combined to generate in him a raft of other ailments but surprisingly had little effect on hasten his demise. Benny opined that it was truly amazing given Mac’s track record, that he had lived as long as he did! As Benny had discovered, Mac’s last years were spent in residential care in “Village at the Park” Rest Home in Berhampore, Wellington (built on the former site of the old Athletic Park rugby stadium).

On 29 October 2007, it was ‘anchors aweigh’ for Mac. NZ13894 & LX31779 Able Steward (Retd) James Robertson “Mac” Mackay, RNZN and RN, late of Edinburgh, passed away at the age of 83 at the rest home. With no funeral or fanfare, Mac’s remains were discreetly cremated at Karori and, as he had wished, his ashes were scattered at sea. Sadly, no earthy memorial exists for this returned war veteran and sailor.

“O Hear us when we cry to Thee, For those in peril on the sea”

~ Lest We Forget ~

Albainn bheadarrach!

Unknown bequest

When I spoke with Benny, we went over Mac’s final years in some detail. With regard to any medals Mac may have had, experience shows that most missing family medals, if not stolen, are most often found in the possession of another family member or relative. When passed on by the owner or gifted within a family, it is generally done so without the general knowledge of the families involved. If the whereabouts of a veteran’s medals is queried, often many years after the veteran has gone, no-one but the current holder of those medals knows where they are. Others who are oblivious to this fact tend to assume they have been lost.

Our discussion prompted the question of what had happened with Mac’s personal effects after his death – he must have had some but how and where were they disposed of? Wherever they had gone, presumably Mac’s medals had gone to? On the other hand they could have been buried/cremated with him, both of which occasionally happens. Since Mac had been a widower and no known children, or other family connections in NZ, or Scotland for that matter, Benny had no idea who could have been a beneficiary of Mac’s estate? Benny resolved to find out, first checking with his own family members for any input.

In the mean time, I would ascertain what Mac’s medal entitlement had been for his WW2 and RNZN service. If there were any unclaimed NZ medals Mac was entitled, I would ask Lt-Cdr Rick’s advice on whether or not Benny could lay claim to these, given he was not a blood relative. If Benny was not able claim, I would arrange replicas of Mac’s entitlement so Benny would at least have a complete representative set of his godfather’s medals for posterity, and to wear on Anzac Day.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Benny contacted me a couple of weeks after our discussion with some startling news. Benny has an aunt who is a Samoan relative from his mother’s side of the family. Aunt Agasi’i had lived with the Ostlers for a number of years after she arrived in New Zealand in the 1970s when Mac had also been staying with the Ostlers. After canvasing his immediate family members for information and drawing a blank, Benny next went to his extended family. Re-calling his Aunt Agasi’i had stayed with the family while he was at school, Benny contacted her to see if she could help and received a most unexpected reply. Unbeknown to Benny and presumable his family, his Aunt Agasi’i had kept in contact with Mac after he left the Ostler home. During the latter years of Mac’s life Aunty had visited him on occasions after he had gone into care at ‘Village on the Park’ rest home.

When Mac died in 2007, having no record of a family, the Rest Home management gave Aunt Agasi’i the few personal effects of Mac’s that remained, namely a briefcase. Aunty told Benny she had not known what to do with the briefcase so, in her words “I just put the whole case away in the ceiling with lots of my other junk” – and there it stayed for the next 16 years until Benny’s inquiry. As he was interested, Aunty was glad to be rid of at least one piece of “junk” from her ceiling and so sent the briefcase to her nephew.

Hidden treasure

When Benny opened the case, he was ecstatic! Inside was a raft of papers that included not only photocopies of Mac’s summarised service in the RN and RNZN, but also his Birth Certificate AND the missing medals he had hoped for! In going through the papers Benny also found Mac’s WILL. In the Will, his Uncle Mac had bequeathed his late wife’s Elizabeth’s jewellery to one of Benny’s sisters and his bed and couch to another. His medals however, he bequeathed to a flabbergasted Benny! Not having the slightest idea Mac had made a Will, let alone include him as a beneficiary, even Benny’s sisters had never mention their bequests of the jewellery or furniture. These had most likely been distributed shortly after Mac’s death, which of course was long after Benny had been posted to Auckland and so were never a topic of conversation during the intervening sixteen years.

Had Benny’s Aunt Agasi’i gone through the contents of the briefcase in any detail, she would surely have found the Will and told Benny that he was a named beneficiary – but she didn’t and so hadn’t. It is very possible Aunty purposely kept her visits to Mac to herself, not wish to ‘rock the boat’ given the rift that had occurred between Mac and David Ostler. In so doing, Aunty had no reason to make mention of the briefcase – everyone had moved on. Interestingly, among the papers in the case was correspondence between Mac and the navy written while he was in Mt Eden during his second ‘visit’. Possibly at a low ebb at the time and without much money, Mac had requested an “Indulgence Passage” of the navy, either on an RNZN or RN ship, or a for paid fare, so he could return to Scotland. The navy replied: as he had not completed twenty years of service, he was not eligible for that assistance and so was declined. Having previously been decline the extension of service to complete 20 years, this decision simply exacerbated Mac’s bitterness towards the navy.

Unclaimed medals

Apart from Mac receiving the Naval Long Service and Good Conduct Medal awarded while still serving in the RNZN, my consultation with Lt-Cdr Rick from the NZDF’s PAM office, confirmed Mac also had a further four unclaimed medals for operational service in Korea & the Near East – not a bad haul for an Able Steward with an alcohol problem, discharged from two Navies after 17 years (non-pensionable) service. The unclaimed medals are:

-

Korean War Service Medal (2001).

NZ Operational Service Medal ** - NZ General Service Medal (Clasp: NEAR EAST) **

- NZ Defence Service Medal (Clasp: REGULAR)

- Korea War Service Medal (offered by the ROK to the Govt of NZ in 2001, the 50th anniversary year of the Korean War, to be awarded to all veterans of the conflict)

** These two Replica medals in the photo above were acquired by the medal mounter before Benny had received approval to claim the originals. The last two medals were instituted after Mac’s death and so he would not have known of them.

Note: Bracketed years in the photograph indicate year the medal was instituted.

This has been quite a journey of discovery for both Benny and myself – thanks for the challenge Benny, a very satisfying outcome for all concerned.

The reunited medal tally is 478