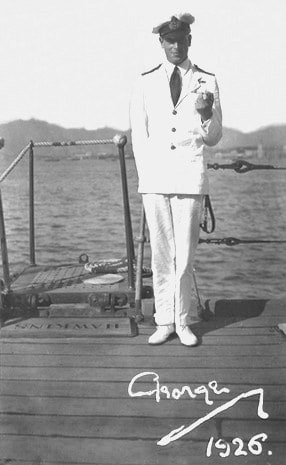

J32493 ~ GEORGE FREDERICK MORRIS, R.N.

When the medals of Royal Navy officer arrived at MRNZ with instructions to return them to the family (if possible), I anticipated a story of a gentleman who had perhaps immigrated to New Zealand after the war or some later date, and subsequently died in NZ. Either that or the medals had finished up in NZ as a result of an overseas purchase by a collector, or even their theft from wherever they came from. Tracing families overseas can be a lengthy process and success often hinges on a healthy dose of luck. I was wrong, but I am getting ahead of myself…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Costume accessories ?

- George Frederick Morris

- Born 4 Dec 1898, Hammersmith, London

- Served in the Royal Navy

- Died in NZ in 1979

The medals comprised, from the left: WW1 – 1914/15 Star, British War Medal 1914/18, Victory Medal. WW2 – 1939/45Star, [Atlantic Star missing], Pacific Star, Defence Medal, War Medal 1939/45 and the Naval Long Service & Good Conduct Medal (GvR).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Who was George Morris ?

Given that three of George’s medals were First World War, I began by locating his Royal Navy service record which can be found on-line for most sailors who served during this period. This gave me all the basics of where and when he was born, what occupation he had prior to entry into the Royal Navy and when his contracted service started. For anything further I also needed to collect the relevant UK census records. These stop at 1911 then jump to 1939 with only name, address and occupation! Beyond that, names and addresses only can be found thereafter which can be highly confusing without more data to identify which “John Smith” you might be looking for. You can imagine the size of the task given the number of George Frederick Morris’s’ that have existed in Britain over the last 400 years – quite a few!

After spending a significant period comparing records and names in households, I was able to confirm that our ‘George Frederick Morris’ was indeed born on 4 December 1898 in Hammersmith, Fulham, a suburb of greater London in the county of Kent. His was an illegitimate birth to a 17 year old mother, Mary Julia Morris (b: Jan 1880) who was as a Domestic Servant. In 1881 Mary’s elder sister Sarah and their father Joseph Morris, a Glassblower, had been admitted to the London Poor House, Joseph to the Poor House Infirmary with an unspecified illness and the children who were too young to be left alone or care for themselves, admitted to live in a Poor House dormitory. Their mother Harriet was listed as a Furrier some distance away in St. George, Southwark however there must have been a disconnection between her and husband Joseph (perhaps permanent?) since there was no-one available to care for the children, and so they necessarily had reside with their father at the Poor House until he was well enough to leave. The cost for their keep would be minimal but a cost none the less their father would need to pay.

The Hammersmith-Fulham records showed that by 1883, Mary Morris and her sisters Sarah, Ellen and Ada were boarding at the Hammersmith Public School, quite a normal practice for the families of the poor. From her schooling, Mary Morris went into domestic service sometime between the ages of 12 and 14, whilst still residing at the school as a boarder.

Despite his unplanned arrival into the world, George Frederick Morris had been duly baptised in Feb 1899, spending his initial years in the Hammersmith-Fulham area with his mother Mary, or in the care of others while she worked. In 1900 Mary and baby George were boarding at 26 Gastien Street in Hammersmith, the small tenement house of Joseph and Ruth Ashcroft Chapman and their three children – Charles 10, William 10 and Frank 8. Joe Chapman was absent at this time however his mother, 75 year old Mrs Harriet Chapman was also residing in the house with them.

In 1901 the Chapman family prepared to leave Gastien Street in preparation to join Joe at his new job in Prittlewell, an inner city area of Southend-on-Sea. As the Chapmans were vacating the Gastien Street house, Mary had to find alternate accommodation for her and George as the house had been re-let to another prioritised tenant. As a result, Mary and George were given temporary accommodation at 31 Milson Street in Fulham, the home of a retired Police Constable and his wife, he working from home as a Wood Carver and Gilder (the application of gold leaf to carvings, statues, picture frames etc). Sometime after this move Mary Morris seems to have disappeared from George’s life but not before he had been taken care of. I located 12 year old George in a 1911 Census once again in the care of the Chapmans who were living at 85 Whitegate Road, Prittlewell, Southend on Sea. George was also registered as a pupil at the Prittlewell junior school.

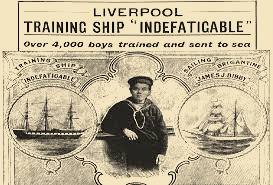

It is unknown if George ever found out who his father was but given that enrollments for TS Indefatigable were for poor or orphaned children whose father’s were seamen, this would suggest either George’s father had been a sailor, possibly dead or had abandoned him and his mother, or Joe Chapman (possibly a merchant marine worker/sailor) had met that criteria as his ‘foster’ father? It is also no known if George ever saw his mother after joining the navy. Ironically a record dated 1933 showed Mary J. Morris (unmarr) to be living at 45 Gastien Street, the very same street in which she had given birth to George at No 33.

School ships

School ships

Until the middle of the nineteenth century the Royal Navy and British Merchant Navy had no recognized training schools for boys entering the service. Education consisted of boys about 15 years old going to sea to be led, guided, bullied and socialized into the culture of the sea. There was no distinction between training for able-seamen (AB), and the training of future ship’s Masters (Captain). Through experience it was possible to rise to the position of Master without any formal training. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century various forms of navigational and seamanship schools were created to remedy the problem.

The two reformatory (borstal) ships, RFS Akbar and Clarence were for boys who had been in trouble with the law. Akbar was for the reform of Protestant Boys, and Clarence for Roman Catholics.

Your in the Navy now !

On 5 December 1911, Boy Seaman (BOY) Morris was 13 when he was accepted as an Indentured Apprentice** by the Royal Navy at Chatham. He was shipped off to Liverpool and would live and work on the boys’ training ship TS Indefatigable for the next 2 years and 9 months. The RN relied on a steady supply of Indentured Apprentices tradesmen to crew their ships, many of the boys remaining for lifetime careers in the navy. The training ships at each of the Royal Dock Yards (sic) – Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth – were usually a retired ship that had been hulked (a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea, stripped of its rigging and internal equipment) and converted to train and accommodate boy sailors. The ships were permanently moored within a naval dock yard and staffed with senior sailor instructors who taught the boys a wide range of seamanship skills. Training ships generally accommodated intakes of around 200 boys.

Officers and Ratings

Royal Navy personnel are divided into two types – officers and ratings. Commissioned officers were the ship’s chain of command and included admirals, captains and lieutenants. Trainee officers (officer cadets) were called Midshipmen and had to pass an exam to become a Lieutenant, while Warrant officers were seagoing specialists such as carpenters, engineers, gunners and paymasters. The crew of a ship was the “ship’s company” and its non-commissioned sailors/seamen were called “ratings” which included boys, stokers, gunners, signalmen, cooks, mates, master at arms, sailmaker, boatswain etc.

Note: ** Indentured Apprentice – An Apprenticeship Indenture was a legal document binding a child (usually around the age of 12 or 13 but sometimes as young as 7) to a master (or mistress) for 7 years or more. A sum of money (premium or consideration) was paid, and in exchange he (or more rarely, she) agreed to train the child in their trade or profession, and to supply them with appropriate food, clothing and lodging for the duration of the apprenticeship.

BOY II G.F. Morris, Royal Navy

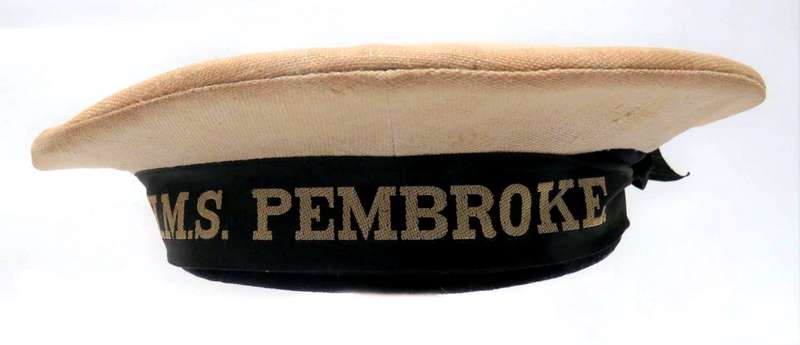

After almost three years of schooling, seamanship training and indoctrination for a life afloat aboard HMS Indefatigable, Boy Seaman Morris’s career proper in the Royal Navy began on 9 September 1914. Advanced to Boy Seaman 2nd Class (Boy II), just four weeks after the declaration of war by Britain on Germany on 4 August 1914, he reported to HMS Pembroke situated within HM Dock Yard Chatham (HMDY Chatham), his administrating unit and barracks. Pembroke is one of many such shore-based ‘ships’ commonly referred to as ‘stone frigates’.** Boy II George Morris, all 5 foot 2¼ inches (158cms) of him, was still three months short of his 16th birthday when he signed the dotted line binding him to the Royal Navy for 12 years as an Indentured Apprentice.

HMS Powerful II

His trade training began on HMS Powerful II at HM Naval Base at Plymouth in Devon. HMS Powerful II had previously been HMS Andromeda (1897), one of eight Diadem-class protected cruisers built for the RN in the 1890s. Her last operational service had been on the China Station in 1912 with the 9th Cruiser Squadron of the new reserve Third Fleet. In 1913 Andromeda was returned to Devonport, converted to a boys’ training ship and renamed Powerful II. She was again renamed Impregnable II in Nov 1919 and finally, HMS Defiance on 20 January 1931 when she became part of the Royal Navy’s Torpedo School.

The Sailmaker

Boy II Morris’s first three months in uniform from Sept-Dec 1914 were spent on Powerful II while learned what the ‘real’ navy was like as well as the basics of his chosen trade of Sailmaker. In days of old, a seagoing sailmaker and his Mates (assistants) were responsible for maintaining the ships’ sails and all canvas work – there was never any shortage of work for a the sailmakers. Sailmaker’s Mates (a leading rate) were known somewhat derisively as “idlers” as they were always too busy to ‘stand watch’ on the ship. Another sailmaker practice when a sailor was killed or died at sea, was to sew the body into his canvas jacket, ensuring that a last stitch went through his nose just to make sure he was dead, before being sent over the side to ‘Davy Jones locker.’

From the design, manufacture and repair of sails, a sailmaker was also required to make and repair pennants and jacks (ensigns/flags), deck buckets, maintain rigging, ropes and anchors. The sailmaker of George’s day also had responsibility for steel cables as well as the myriad of items and finishes made of fabric, leather and canvas. The sailmaker typically worked in a ‘sail locker’ on the ship, or a much larger ‘sail loft’ on shore, with a very specialized set of tools as represented by two of the most important one’s depicted on the RN Sailmaker’s trade badge – the Fid and Marlinespike.

The fid is a conical tool usually around 15-30cm in length, traditionally made of wood or bone used to work with rope and canvas in marlinespike seamanship. A fid differs from the marlinspike in material and purposes. A marlinspike is used in working with wire rope, natural and synthetic lines, may be used to open shackles, and is made of metal. These can be up to 1500 mm in length or as small as can be found as an attachment on a pocket knife.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

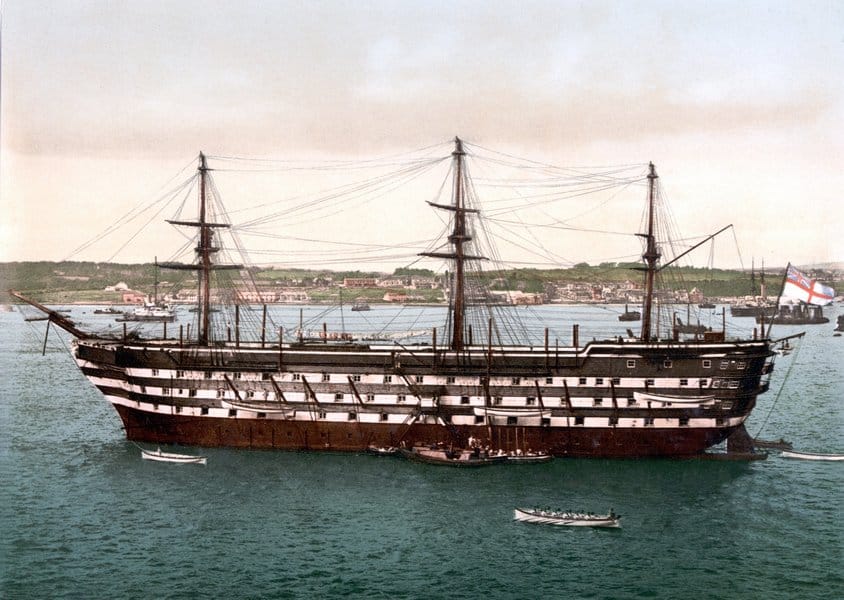

In January 1915, Boy II Morris was advanced to Boy Seaman 1st Class (Boy I) and sent to a second training ship and floating barracks at Devonport. HMS Impregnable (formerly HMS Inconstant) was an unarmored, iron-hulled, screw frigate built for the Royal Navy. When completed in 1869, she was the fastest warship in the world[and was assigned to the Channel Squadron. The ship was reduced to reserve 1882 and became an accommodation ship for the overflow from the naval barracks at Devonport in 1897. Inconstant was taken out of service in 1904 and became a gunnery training ship in 1906 assigned to the seamen boy’s training establishment HMS Impregnable.

Note: ** Stone Frigate (or ‘concrete ship’). A colloquial name for a naval shore-based establishments. These establishments are also considered to be ships for the purposes of command and discipline, and are named as such, e. g. ‘His/Her Majesty’s Ship’ – HMS (ship name) may be an operational ship, a permanently moored vessel (training ship or accommodation facility/billet), a shore-based facility (‘stone frigate’) such as a headquarters, training school, reserve or cadet unit.

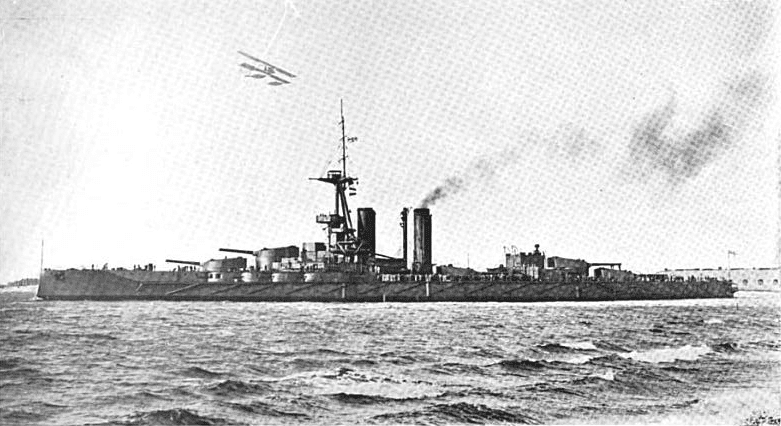

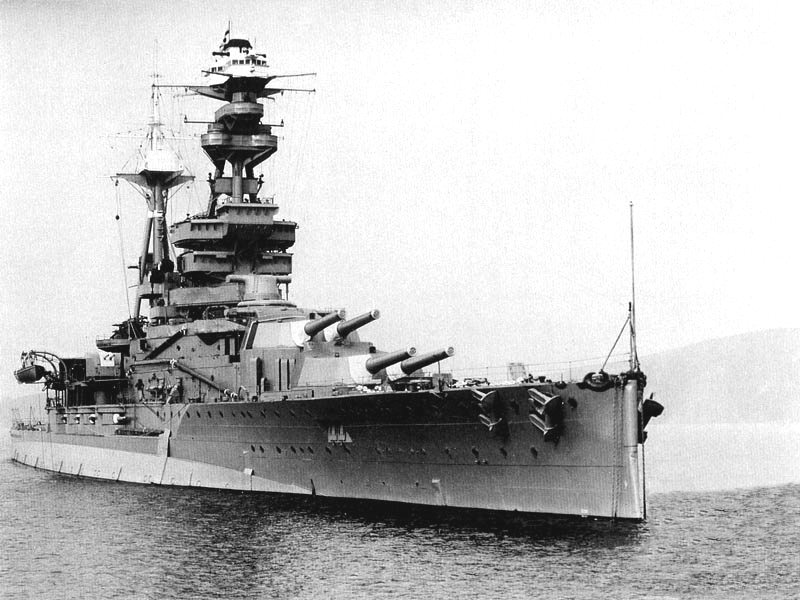

While on HMS Impregnable, Boy I Morris’s sailmaker training continued until he was ready to join an operational ship for ‘live’ experience at sea. The First World War had not slowed the pace of his training, if anything it had increased as the naval commitment to WW1 ramped up. Boy I Morris’s first posting afloat was to be on the HMS Iron Duke which he joined on 21 September 1915, three months short of his 17th birthday. Now a fully fledged Royal Navy sailor, his ‘Boy’ status ceased and he became Ordinary Seaman (OS) George Morris. Ordinary Seaman is the most junior adult rank on a ship.

Jutland (Denmark), 30-31 May 1916

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the Imperial German High Seas Fleet and a Battle Cruiser Fleet, totaling five battle cruisers and 22 battleships, departed the Jade (the River Jade at Wilhelmshaven was where the German Fleet were assembled) early on the morning of 31 May.

After intercepting radio communications that warned of an operation by the German Fleet off the south-western Jutland (Norwegian) Peninsula, the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet and Battle Cruiser Fleet, eight battle cruisers and 29 battleships, to sea the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet. On the day of the battle, Iron Duke steamed with the 4th Battle Squadron.

The following are extracts of the action on 31 May 1916, is from Wikipedia:

“The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battle cruiser formations in the afternoon, but by 18:00 hours, the Grand Fleet approached the scene. At around 18:14, two large-calibre shells fell near Iron Duke but caused no damage. Fifteen minutes later, Iron Duke had closed to effective gunnery range — some 26,000 yards (24,000 m) — of the German fleet, and took the dreadnought SMS König under fire. Iron Duke‘s first salvo fell short, but the next three were on target; the ship’s gunner claimed at least six hits on the German battleship. In fact, they had scored seven hits on König and inflicted significant damage.

Shortly after 19:00, fighting around the disabled German cruiser SMS Wiesbaden—which had been badly damaged earlier in the engagement—resumed. Iron Duke opened fire on the crippled cruiser and nearby destroyers with her secondary battery at 19:11 at a range of 9,000 to 10,000 yards (8,200 to 9,100 m). Iron Duke‘s gunners claimed to have sunk one of the destroyers and hit a second, but they had in fact missed their targets entirely. Shortly thereafter, the German destroyers attempted to launch a torpedo attack on the British line; Iron Duke began firing at 19:24. The sinking of the destroyer SMS S35 is credited to a salvo from Iron Duke, but determining which ship fired which shells in the melee was difficult.

Following the German destroyer attack, the High Seas Fleet disengaged, and Iron Duke and the rest of the Grand Fleet saw no further action in the battle. This was, in part, due to confusion aboard Iron Duke over the exact location and course of the German fleet; without this information, Jellicoe could not bring his fleet to action. At 21:30, the Grand Fleet began to reorganise into its nighttime cruising formation. Early on the morning of 1st June, the Grand Fleet combed the area, looking for damaged German ships, but after spending several hours searching, they found none. Iron Duke returned to Scapa Flow, arriving at 11:30. Over the course of the battle, Iron Duke had fired ninety rounds from her main battery, along with fifty rounds from her secondary guns.”

Throughout the battle, HMS Iron Duke whilst experiencing a number of near misses mainly from overshoot, was not fired upon by the enemy and therefore sustained no casualties.

German losses in the battle were less than the British, but strategically, the German Fleet only ventured to sea on two further occasions before the end of the war. Jutland was a battle that the British did not have to win, but if the Germans had won, they would have gained command of the sea and would have won the war. The total loss of life on both sides was 9,823 personnel: the British losses numbered 6,784 and the German 3,039.

British – 113,300 tons sunk

- Battle cruisers Indefatigable, Queen Mary, Invincible

- Armoured cruisers Black Prince, Warrior, Defence

- Flotilla leader Tipperary

- Destroyers Shark, Sparrowhawk, Turbulent, Ardent, Fortune, Nomad, Nestor

German – 62,300 tons sunk

- Battle cruiser Lützow

- Pre-dreadnought Pommern

- Light cruisers Frauenlob, Elbing, Rostock, Wiesbaden

- Destroyers (heavy torpedo-boats) V48, S35, V27, V4, V29

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When the First World War ended, HMS Iron Duke was put to work in the Mediterranean as the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet. While on Iron Duke, OS Morris gained his first promotion to able rate – Able Seaman (AB) in January 1917. This signaled the fact he had completed and passed his trade training to be considered a competent junior sailmaker. AB Morris’s tour of duty afloat on Iron Duke came to an end on 8 July 1918, the end of the war for the ship’s crew.

Once the Armistice had taken effect in Nov 1918, Iron Duke was directed to the Black Sea to undertake operations in support of the White Russian army during the Bolshevik uprising. Iron Duke remained on the Active List until Dec 1931 when she was Paid-Off and stripped of her military hardware. The ship was then deployed to Portsmouth as a Gunnery Firing Ship, and after 1936 was used as a training ship. In August 1939, she attended the Review of the Reserve Fleet and took up her war station on 26 August for use as a depot ship** at Scapa Flow. She was also one of the last British battleships to be coal fired.

HMS Sandhurst (1905)

The first GCB is awarded upon the completion of two years service with the required standard of conduct not falling below “Very Good”. The second GCB can be granted after a further four years, or six years total service, and the third after another six years, or twelve years total service. Further good conduct badges could be awarded every six years.

GCBs are important in a sailor’s service as they represent that he has been well reported, is of good character and free from serious disciplinary infractions, both of which could affect his advancement and consequent pay increases. GCBs are also a pre-requisite for the award of the navy’s long service medal, three GCBs and 15 years of exemplary service being required for the Naval Long Service & Good Conduct medal.

Note: ** Depot Ship – an auxiliary ship used as a mobile or fixed base for submarines, destroyers, minesweepers, fast attack craft, landing craft, or other small ships with similarly limited space for maintenance equipment and crew dining, berthing and relaxation.

Shore training

In March 1920, AB Morris was promoted to leading hand, or Leading Seaman (Corporal equivalent) indicating he had taken his first step into the role of a supervisor, known universally as a junior non-commissioned officer (JNCO). In terms of sailmakers, a leading hand is known as a “Sailmakers Mate”. A shore posting was next to attend further NCO training at HMS Calliope which would equip him for advancement to the next rank of Sailmaker (Petty Officer = Sgt equivalent). Calliope was a Royal Naval Reserve ‘stone frigate’ that used an old Calypso-class third-class cruiser, HMS Calliope, as its drill ship. HMS Calliope was situated in the north-east of England at Gateshead, Tyne and Wear near Newcastle.

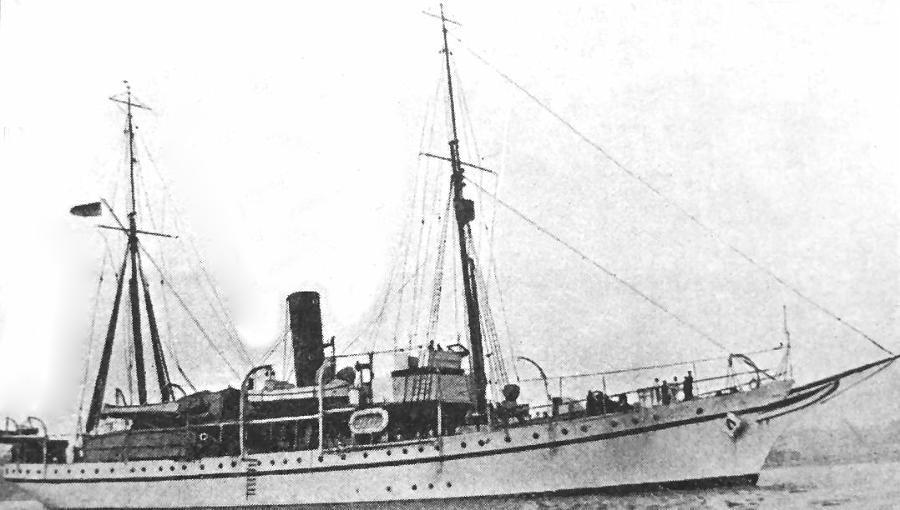

Promotion training concluded in August and LS Morris returned to Pembroke-1. His return to se came in July 1921, this time on a relatively relaxed but busy cruise on the Mediterranean Station. HMS Endeavour, the 10th and last ship to bear the name, was a survey ship used for underwater surveys of the ocean floor, usually to collect data for mapping or planning underwater construction or mineral extraction. A name steeped in naval history, Endeavour’s namesake predecessor had been an RN schooner that was in service in 1778, and prior to that was Cook’s Endeavour! The survey ship had been launched in 1912 and was later used during WW2 as a Depot Ship from 1940-1946. When LS Morris joined Endeavour at Alexandria, Egypt she was surveying the harbour and Abu Kir Bay. Throughout the 19 months he spent aboard HMS Endeavour regular voyages were made for survey tasks to Malta, Gibraltar, Cyprus and other ports of interest within the Med. George’s promotion to the dizzy heights of Sailmaker, a rank that carries considerable sway among non-commissioned sailors, was announced shortly before Endeavour’s return to Chatham in August 1923.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

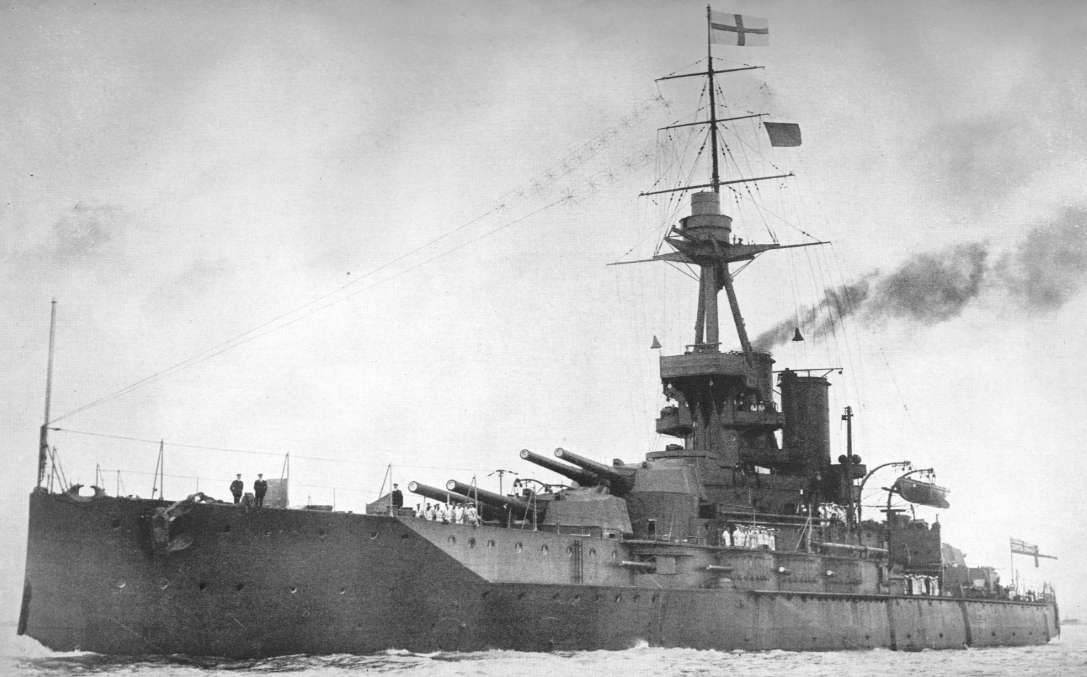

HMS Benbow (1913)

A year ashore at Pembroke-1 preceded PO Morris’s next posting afloat in Sep 1924 to HMS Benbow (1913), another of the Iron Duke-class battleships which was also stationed in the Mediterranean. HMS Benbow had been in the Mediterranean from 1919 to 1920 providing naval gunfire support to the White Russian Army in the Black Sea during the Bolshevik Revolution. She remained on station in the Med until 1926 before being transferred to the Atlantic Fleet.

In November 1925, PO Morris returned to HMS Calliope to complete the promotion course for advancement in his trade to Chief Petty Officer (CPO), returning in February 1926 for posting to the heavy cruiser HMS Hawkins.

HMS Hawkins (D86)

Intent upon remaining in the Navy, he applied for another six year extension before taking an extended period of shore leave.

Re-engagement and family

George had good reason for wanting extended leave; he was getting married to Alice Maude OMAN (1904-1982) in October 1928 at Medway in Kent. Alice Oman was an English woman who was born in India, the fourth of seven children born variously in India, Gibraltar and Malta. It may be reasonable to assume in the absence of information to the contrary that George had met Alice during one of his postings to the Mediterranean Station, an area where Alice’s father had soldiered. Alice’s mother was Alice ROBINSON (1876-1952), herself born in Karachi, Pakistan, until she married Alice’s father, Francis James “Frank” OMAN, then a Sergeant of the Royal Artillery who was based in India.

Frank Oman was a nineteen year old photographer when he enlisted at Dover Castle in 1893, eventually rising to the rank of Warrant Officer Class 2, the Battery Quartermaster Sergeant (BQMS) of the Siege Artillery School at Larkhill, Wiltshire. Sergeant-Major Oman took his discharge from the army in 1920 after completing more than 27 years of continuous service, 21 of which had been at overseas posts accompanied by his family.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Long service rewarded

In March 1929, PO Morris was ashore at Pembroke during which time he completed the necessaries to be appointed a Boatswain Sailmaker, or Bo’sun as it more correctly pronounced. George returned to work to find his re-engagement for a further six years had been approved with effect from 1 July 1929. He also had the opportunity to attend a specialist course of training at RAF Manston in north-east Kent which gave him firsthand experience in the application and repair of fabric covered aircraft fuselages and wings.

Conveniently, George and Alice were renting in Medway, a mere two kilometers from the Dockyard so it was hardly surprising George was not at sea on 19 Sept 1929 when Alice increased the size of the Morris family by one – George and Alice welcomed their first and only child Valerie Jean MORRIS born at Gillingham, Kent.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

HMS Marlborough (1912)

In December 1929, PO Morris was awarded his 3rd GCB having just paid on to HMS Marlborough (1912). Another of the Iron Duke-class battleship, named in honour of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, PO Morris served for 18 months on Marlborough from Dec 1929 to May 1931. During this time the ship’s 3-inch anti-aircraft guns were replaced with more powerful 4-inch guns. In January 1931, Marlborough served as the 3rd Battle Squadron’s Flagship, relieving the Emperor of India. She remained in the position for only five months, being decommissioned on 5 June 1931.

It was back to Pembroke-1 for George in May 1931 to spend time with Alice and Valerie while his employment consisted mainly of instructional and supervision duties. He also oversaw the stripping of all useful fittings from the old HMS Defiance (1861), the last of the wooden line-of-battle Renown-class battle ships. HMS Defiance had been used as the Royal Navy’s Torpedo and Mine School at Devonport since 1884 and finally sold off in 1931.

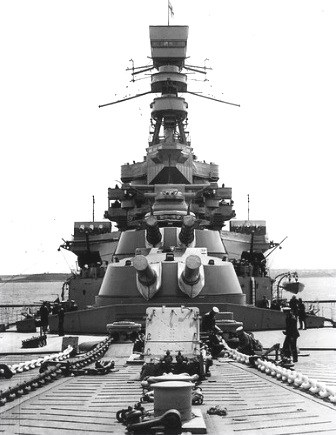

HMS Royal Oak (08)

Between the wars, Royal Oak was de-commissioned in readiness for a re-fit which would involve the removal of her torpedo tubes, and twin 4-inch Anti-Aircraft guns fitted to replace the single mount 4-inch guns. After more than a year in re-fit, Royal Oak was ready for sea trials and re-commissioning. Attempts to modernise Royal Oak throughout her 25-year career could not fix her fundamental lack of speed and, by the start of the Second World War, she was no longer suitable for front-line duty.

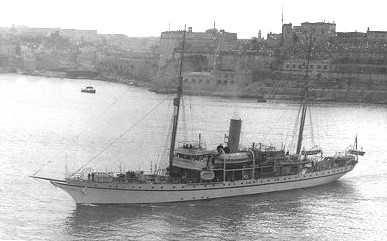

HMS Titania (F32)

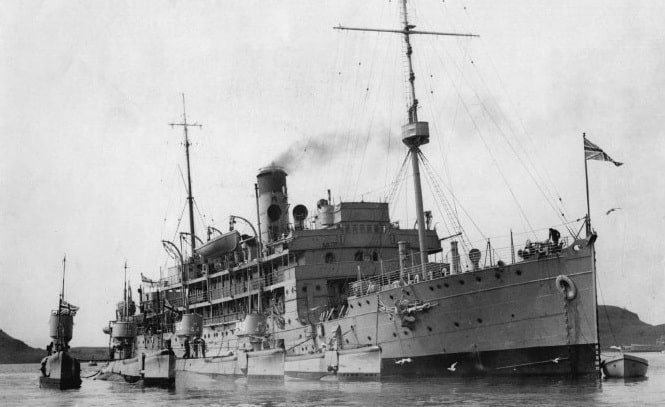

From January to March 1933 A/Bo’sun Morris served on HMS Titania (F32), a Depot Ship that was being re-commissioned for service with a submarine flotilla.

Built in 1915 as a merchant ship for the Austrians, with the outbreak of war Titania was commandeered and converted to a submarine Depot Ship. She was based in Hong Kong from 1920 to 1929 as part of the 4th Submarine Flotilla. In Oct 1930 after commissioning at Chatham, she joined the 6th Submarine Flotilla at Weymouth, Portland. In 1935 she was temporarily placed with the 3rd Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, returning to the 6th in 1936. In May 1937, HMS Titania took part in the Coronation Review at Spithead as the Flag Officer Submarines’ Flagship. She remained with the 6th until being re-fitted in 1940 and transferred to Holy Loch for the remainder of the war. During the time CPO Morris was with her, a good amount of time was spent supporting the submarines on exercises.

HMS Renown (72)

HMS Renown participated in King George V’s Silver Jubilee Fleet Review at Spithead on 16 July. Together with Hood, Renown was sent to Gibraltar to reinforce the Mediterranean Fleet during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935–36 and transferred to Alexandria in January 1936 where she was assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron. She returned home to Portsmouth in May 1936 and rejoined the Home Fleet.

After 18 months aboard Renown, CPO Morris left the ship after the euphemistically named “Spring Cruise” of 1935-36 and returned to Pembroke-1 at Chatham for a well earned period ashore from July until December 1935. In July George had re-engaged for an additional six years service which would bring his total to 24 years RN service.

HMS Endeavour

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Commissioned Warrant Officer

The year 1938 heralded a significant step up in both rank and responsibility for Bo’sun George Morris. The Royal Navy was about to go to war for the second time in George’ Morris’s navy career, at a time when he was selected for promotion to commissioned Warrant officer. While most of us can generally identify the difference between commissioned officers and non-commissioned officers (e.g NCOs), the navy then had a unique system of commissioned Warrant officers that was introduced around 1924.

From the early days of the RN, specialists such as a ship’s carpenter, boatswain and gunner were vital to the safety of all on board, and were accordingly ranked as ‘officers’, reporting directly to the Captain. Warrant officers have always been the heads of specialist technical branches of the ship’s company requiring a very high level of experience and detailed knowledge, their ranks included master, purser, engineer, boatswain, gunner, carpenter, surgeon, armourer, chaplain, cook, master-at-arms, sailmaker and schoolmaster.

A sailor became an ‘officer’ by virtue of being awarded a Warrant that was issued by the Board of the Admiralty, i.e. he was a commissioned Warrant officer and as such, whist at the pinnacle of the ‘lower deck’ ranks, did not have Wardroom (the officers mess on a ship) status. A commissioned Officer on the other hand was appointed with a Royal Commission issued on behalf of the Sovereign. Warrant officers were junior to Commissioned officers, but senior to all other naval Ratings (the rank & file seamen from Boy to Chief Petty Officer). They were also saluted by junior ranks.

These specialists were attached to the ship throughout its life, whether in commission, or “in ordinary” (“laid up”). Their professional and man-management experience enabled them to make an invaluable contribution to the running of a ship and did much to ensure a high standard of availability of equipment and services at sea. First and foremost, Warrant officers were responsible for ensuring a ship was fully prepared for its role and tasks, be it in peace or war thus enabling the commissioned officers to dedicate themselves to “fighting the ship” with the tactics required to defeat an enemy.

There were five specialists on a ship at this time ranked as commissioned Warrant officers:

- Warrant Boatswain (Bo’sun) – “Running” and “standing rigging”, sails, anchors and cables. He was also responsible for the maintenance of discipline on board. This category also served in Royal Dock Yards for similar duties.

- Warrant Master – Navigation of the ship

- Warrant Carpenter – Hull maintenance and repair

- Warrant Clerk (Writer) – All correspondence

- Warrant Gunner – Guns, ammunition and explosives

- Warrant Cook – Feeding all on board

One of the most important capabilities required of all specialisations at Warrant officers was of instructional competence as theirs was the responsibility for training and developing the sailors of their particular specialisation. They were also required to have a second operational sea-going skill, usually that of either gunner or torpedoman.

Requirements for promotion

In general, all candidates for Warrant rank were required to have at least qualified for Petty Officer rating (Sgt equiv) and in some cases to have served as such for a number of years (as had George). Candidates were also required to have achieved the same educational standard by having passed the Higher Educational Test (a standard slightly less than that of the pre-1944 School Certificate). Although most branches had professional examinations these varied considerably between branches and some promotions were made on the basis of “long and zealous service.”

Further advancement to “commissioned officer” from Warrant rank was a slow process and generally required 10 years well reported service as a Warrant Officer. The number of promotions was also limited by the number of billets (positions) allowed for that rank. This meant that few Warrant officers could expect any further promotion until they were over 40 years of age. It was a major cause of disquiet to them since it showed little appreciation of their contribution and the advantages to be gained by recognising their merit. Accordingly, an increasing number of Warrant officers’ were promoted directly to Lieutenant rank on their retirement from the RN after 1937.

The specialists listed above and others created later, retained their distinctive rank and status until 1949 when the rank of ‘warrant officer’ was abolished. At that point all warrant officers became (commissioned) branch officers, with the category of the Special Duties officer being added in 1956. The warrant officer rank in the RN was re-instated in 1973, and from 01 April 2022 included a Warrant Office Class 2, superior to a Chief Petty Officer and junior to a Warrant Officer Class 1.

Note: ** the date year on the photograph is believed to be incorrect as George Morris, dressed here in the uniform of a commissioned Warrant officer, was not promoted to this rank until 1938!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

World War II

By the time CPO Morris had paid off HMS Endeavour the Royal Navy was in a full state of preparedness for possible war. On returning to HMS Pembroke he was appointed Bosun of the Yard at Pembroke in December 1939, a senior appointment that encompassed responsibility for the discipline and routine of all personnel posted to HMS Pembroke. His responsibilities were expanded in October 1942 when he was promoted to commissioned Warrant officer rank as Bosun of the Yard for the whole of the DY Chatham. One must appreciate that all of the Royal Dock Yards through out the war were extremely busy places with building, re-fitting and repairing ships together with a huge workforce, most of it civilian. HM Naval Base Devonport (then DY Devonport) for instance is today the largest naval base in Western Europe, and has been supporting the Royal Navy since 1691. The vast site covers more than 650 acres and has 15 dry docks, four miles of waterfront, 25 tidal berths and five basins. The base employs 2,500 military personnel and civilians. During WW2, similar numbers of personnel were no doubt present at DY Chatham.

In October 1944 Warrant Bo’sun Morris made his ‘escape’ from Chatham by way of an overseas posting to Dock Yard Kilindini at the Port of Mombassa, Zanzibar in East Africa, now known as Kenya. WO Morris was appointed Master Rigger of Kilidini together with two other Master Rigger WOs junior in seniority to him. During World War II, while Kenya was a British colony, Kilindini became the temporary base of the British Eastern Fleet from early 1942 until the Japanese naval threat to Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) had been removed. Nearby, the Far East Combined Bureau, an outstation of the British code-breaking operation at Bletchley Park, was housed in a requisitioned school (Allidina Visram High School, Mombasa) which had considerable success in breaking Japanese naval codes.

Warrant Officer George Morris returned to Chatham in October 1945 after the war had ended. However, his time at home would be short with only three months respite before he was put to sea again in January 1946, this time on the aircraft carrier HMS Implacable (R86).

HMS Impacable (R86)

HMS Implacable returned to the UK June 1946, placed in Reserve and re-fitted. Implacable acted as a deck-landing training ship for the Home Fleet between 1946-49, when she once again became an operational carrier to serve as the Flag Ship for the Home Fleet in 1949. Due to manning problems in 1950, many Home Fleet ships had to be withdrawn from operational service and so HMS Implacable was deployed to the Training Squadron between Jan 1952 to Sep 1954 when she was paid off, and broken up in Nov 1955.

Return to Chatham, promotion & retirement

WO Morris’s posting as Bo’sun on Implacable lasted some 18 months. It was also his last ship before paying off in July 1947 and returning to Chatham as Bosun of the Yard. With a clear intention of ending his naval career by the age of 50, WO Morris was made a commissioned officer with the rank of Lieutenant (equivalent to an Army captain) on 17 October 1948. Being elevated to a commissioned officer was a common practice at this time before retirement, in recognition of the years of dedicated service in the ranks as a highly respected and senior trade specialist.

For his remaining time in the navy, Lt. Morris RN (commissioned officers are entitled to “RN” after their name to differentiate from army rank) was placed in charge of the Royal Naval Barracks (built between 1897 and 1902) at HMS Pembroke where no doubt many a young sailor benefitted from his wise counsel and years of experience as a senior sailmaker.

Lieutenant George F. Morris R.N. said his final farewells to the Royal Navy in December 1948 and retired to his and Alice’s home at 42 Crombie Road, Chislehurst in Kent.

Awards: 1914/15 Star, British War Medal 1914/18, Victory Medal, 1939/45 Star, Atlantic Star, Pacific Star, Defence Medal, War Medal 1939/45, Naval Long Service & Good Conduct Medal (entitled to a clasp for an additional 15 years)

TS Indefatigable (school ship): Dec 1911 – Sep 1914 = 2 yrs 9 mths

Royal Navy service: Sep 1914 – Dec 1948 = 34 yrs 3 mths

Total RN service: 37 years

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

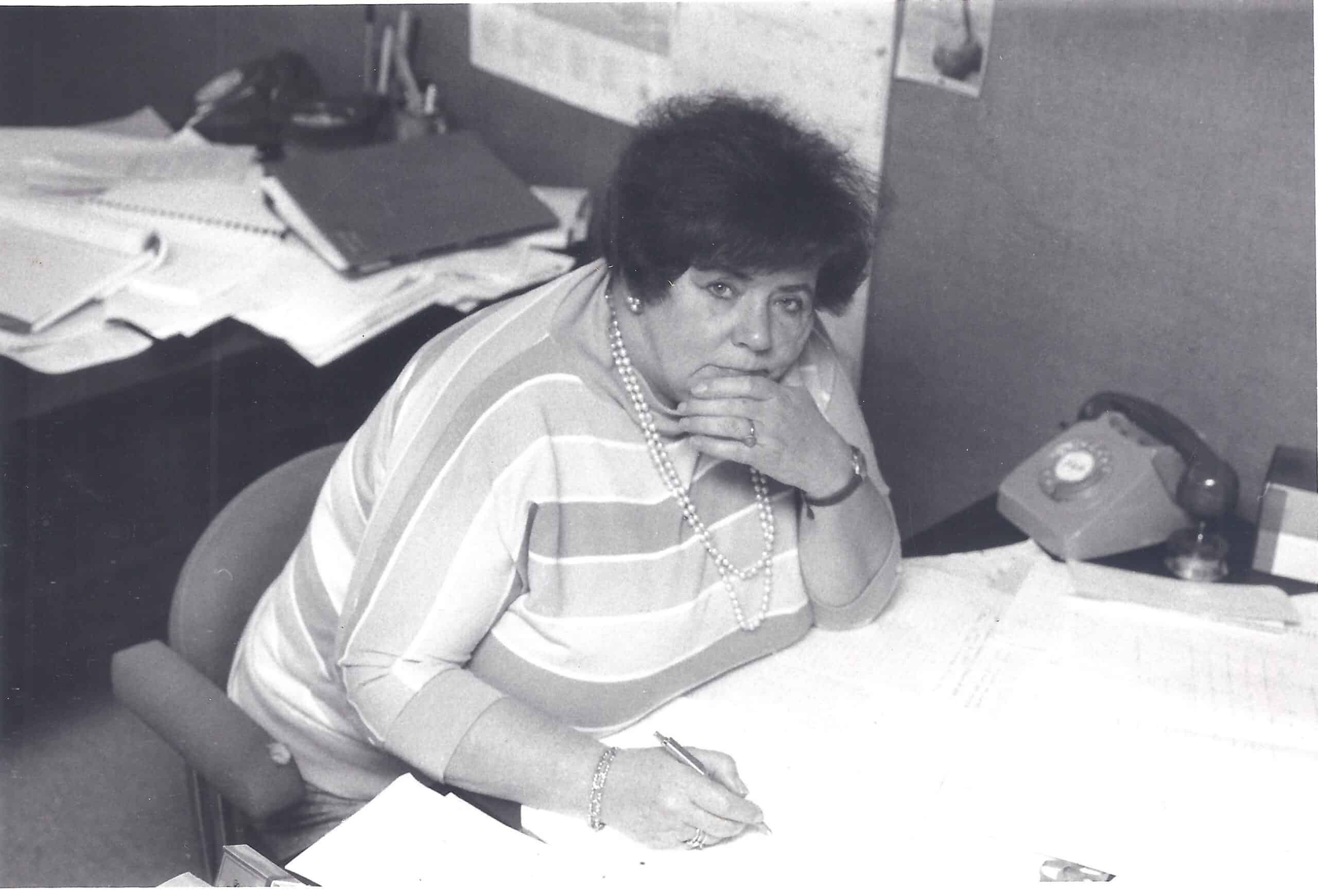

When George retired in 1948, his daughter Valerie had just turned 20 and was into her second year of a seven year course of study for an architectural degree at the University College of London (UCL). From this point on, the details of George and Alice’s life are unknown to me other than by 1965 they had undergone one final change of address to 14 Western Avenue, Bridge in Canterbury, Kent. It was here that Lieutenant (Rtd) George Frederick Morris, RN died on 23 June 1975 at the age of 76. Alice his wife died a little over six years later on 8 July 1982 aged 78.

~ Lest We Forget ~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Last of the line …

The information above is what I have managed to collate from George Morris’s on-line ancestry, his recorded movements together with a very confusing and sketchy singular page of his RN history from 1914 to 1932. Beyond that has taken some effort to link his service with ships. Contrary to my initial thought that because his medals were found in New Zealand, George and/or Alice might have lived, or at least visited, New Zealand but of this I could find no evidence in either immigration or census records on NZ and the UK. The situation became somewhat more confusing as I scoured the NZ census records as there were several persons named “George Frederick Morris” and even “Alice Maud/Maude Morris”. Two of the “Alice’s” even had birth dates only months apart from George’s wife! All of these needed to be checked out to either confirm they were relevant or to eliminate them. After working through these, none were connected to our George and Alice Morris. That left only one other person who could have had any influence on the outcome – their only daughter Valerie Jean Morris. There were very few relevant records for Valerie Morris in the UK except for her birth and one for a residential address with her parents in Medway.

This all changed when Valerie was located in NZ records, however, I am getting ahead of myself again. The credit for unraveling the connection between George and Alice, and their daughter in New Zealand must go to Mike Stanley, one of MRNZ’s part-time researchers in Dunedin. It was Mike who made the breakthrough after I had given the bare bones of the case to work with like, who George was, who Alice his wife was, where they married and who her family was. What I was looking for was a connection to New Zealand as this was where the medals had resided for over 35 years.

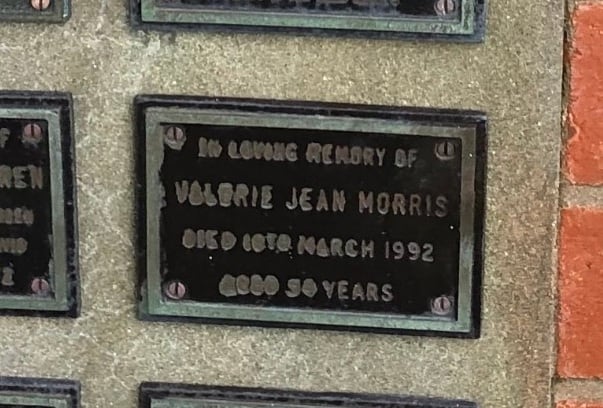

Mike came back after a couple of weeks with Valerie’s emigration to NZ in 1953, her Naturalization as a NZ citizen in 1957, and the fact she had died in Hastings in 1992. Valerie had been an architect while in NZ which helped with tracing her movements both in and out of NZ via the Electoral Rolls. Because Mike was unable to find any evidence of a marriage, or another child connected to Valerie, we had to assume she was an only child and so was the last of George Morris’s immediate family.

Where there ‘s a Will ….

Having found the correct Valerie Morris, with Sam’s confirmation that she had died in Hastings her date of death was located: 16 March 1992, age 62. Valerie had been cremated and her ashes interred in the Karori Cemetery Columbarium i Wellington. Confusingly a second “Valerie Jean Morris” appeared in the census records who had also lived in Island Bay, Wellington in 1979, and who was married to Robert Henry Morris (Managing Director). It was unlikely Valerie had married someone of the same surname and this couple had appeared in only two records, whereas our Valerie Morris appeared at several different addresses in the same years as this couple. As Valerie had been a life-long spinster and was childless, the problem for me was determining whether or not there was someone else who had a legal entitlement to George’s medals?

Mike had also found Valerie’s Will on-line which turned out to be the unexpected key to determining where the medals went. The appearance of the name “Samuel Amuri Robinson” in her Will named him as Executor and Trustee of Valerie’s estate. Mike had traced Sam Robinson to the Hawkes Bay and had made contact with him. Sam confirmed Valerie had been an only child and that she had never married, nor had any children to the best of his knowledge. Sam also revealed that Valerie had left him her father’s naval telescope (seen below).

The clincher for me was the manifest of a passenger ship called Largs Bay which just happened to have listed 200 persons being migrated to NZ under the auspices of the Department of Labour. The Largs Bay had arrived in Auckland on 3 Apr 1953 with a “Valerie Jean Morris, Age: 23, Status: Spinster, on board. Another record also showed that on 9 July 1957 Valerie Morris became a Naturalized NZ citizen. Mike had found Valerie had spent time working in Fiji and Hong Kong, confirmed by a 1969 immigration record that showed, “Valerie Morris, Age: 40, Status: Unmarried” had arrived in Auckland from Suva, Fiji, ex-Vancouver on the P & O’s Oriana! Further, three residential addresses in Wellington Central and the Hutt Valley supported the presence of Valerie Jean Morris at addresses in Karori, Island Bay, Miramar and Stokes Valley.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Had Valerie been in possession of her father’s medals at some stage, or had they arrived in NZ by other means as suggested above? .. and how did they finish up in the Khandallah Arts Theatre? Who was I going to return George’s medals to? Finding suitable answers was not looking promising.

As I contemplated this, I also reasoned that since George Morris’s medals had been found in Wellington, there were really only two credible circumstances that could account for this – they had either arrived with, or had been sent to, someone related in NZ who had subsequently either lost or disposed of the medals, or, the medals had been purchased privately or via public auction from the UK, and subsequently had been lost, gifted to the theatre, or stolen.

To that end, I asked Michelle if she could find out whether Valerie had ever been a member of the Arts Theatre, or was there someone who remembered having contact with her for some reason, or possibly had received the medals from her? Nothing – Valerie had not been part of the theatre and no-one could recall how or when the medals arrived, or even for what reason they might have been in the Theatre, e.g. for a specific production that had required them?

Executor’s instructions

After reading Valerie’s Will I could automatically see that a number of clauses which pertained to her parents George and Alice, were made void on the basis she had not predecease either of her parents. In Valerie’s Will dated 5 November 1972, she had appointed ‘Samuel Amuri Robinson’ of Waipukerau to be the sole Executor and Trustee of her will. Should Sam predecease Valerie, she made provision for this eventuality by stipulating Sam’s next eldest brother to become the sole Executor and Trustees.

Aside from some peripheral benefits detailed for the Executor, Valerie directed after the debts of her estate had been settled, the residuary of her estate be managed as follows: if she pre-deceased her parents, an inventory of her residuary estate was to be sent to them to make a personal selection. Given George and Alice had both pre-deceased Valerie, he in 1975 and she in 1982, that presumably did not happen. Further, Valerie stated that should both parents pre-decease her (which they did), then her “entire residuary estate was to belong to the Executor and Trustee of her Will for his own use and benefit absolutely” providing he survived Valerie. Finally, Valerie had stipulated that the beneficiary (whomever that would be), apart from her real estate, was to retain her residuary estate and that it was not to be sold.

Executor and medals recipient

The answer was now clear. After contacting Sam Robinson, explaining the circumstance of George’s medals and our discovery of Valerie’s Will, my first question was what the connection had been between her and the Robinson family? Sam explained Valerie had worked for architectural firms in Auckland and Wellington predominantly for the Ministry of Works and Development where most of her architectural work had been with public buildings and infrastructural construction. She also worked in Fiji and Hong Kong but mostly in Wellington.

The Robinsons being farmers, a big part of their lives was/is Federated Farmers and it was through this organisation they met Valerie Morris. Being a single lady and perhaps somewhat lonely in the city, Valerie had joined Federated Farmers and had been keen to have a holiday on a farm. Sam’s mother, herself a member of the Women’s Division, learned of Valerie’s wish and with six boys, Sam’s mother thought it might be nice to have a girl around for a couple of weeks and so Valerie was invited her to stay. She was mutually befriended visiting whenever she could and spending Christmas with the Robinsons. As a result of their relationship, Valerie had made the Robinsons the beneficiary of her Will in the event her parents predeceased her.

Sam said that Valerie had retired from her position in Wellington after developing lung cancer and moved to Napier. Eventually residential care became necessary and she died at the Cranford Hospice in Hastings in 1992. Prior to Valerie’s death, Sam said he had been the beneficiary of George Morris’s telescope which features in a photograph he has, along with a series of photographs which encompass some of the highlights of George Morris’s life. As for Valerie’s connection to the Khandallah Arts Theatre, Sam had no knowledge of any, and neither did Michelle Soper, not during her 35 plus years with the theatre.

What an outcome! The mystery to some extent had solved itself once Valerie Morris’s Will was read. It was unequivocal: Sam Robinson would be the beneficiary of George Morris’s medals. I was unable to solve the riddle of how the medals had ended up in the Arts Theatre and despite Michelle’s efforts to elicit a connection from the members of the theatre, no-one had the remotest idea of when or how the medals had got there.

My conclusion was that there were potentially several possible answers:

- Valerie had been the recipient of her father George’s medals, sent to her after her either after her father George’s death in 1975, or after her mother Alice’s death in 1982 (most likely).

- Valerie may have then either loaned them to someone connected to the theatre as a costume prop for some production, possibly around the time she died, which would likely have resulted in the medals being retained at the theatre, particularly as Valerie had left the Wellington area and died in Napier (less likely).

- The medals may have been gifted (or sold) by Valerie to someone, or the medals may have been stolen from her residence and subsequently purchased as a theatre prop (least likely).

Epilogue

The outcome of this case could not have been more perfect. Sam Robinson and his brothers manage a very large family farm property in the Hawkes Bay and have enjoyed significant success in their rural pursuits at both personal and national level. Sam is a degreed farmer, BSC (Agr), very active in the rural sector and rural politics. He has also found time in the past to serve, like his father, as a Territorial Army officer with the 7th Battalion (Wellington [City of Wellington’s Own] and Hawkes Bay), RNZIR. This seemed to be an entirely natural step for Sam considering his father’s pedigree.**

The Robinson family is well attuned to the service and sacrifice that military medals represent. I could think of no better custodians of George Morris’s medals than Sam Robinson and his family, with whom I am confident they will be accorded the respect they deserve, and used to honour George Morris’s Royal Navy service through two world wars, on appropriate occasions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I remain amazed by this case in that although the medals of George Morris were for all intents and purposes ‘lost’ forever to those entitled to inherit them, and that once found, to learn that their destiny had already been pre-determined by a Will created in 1972, was quite unbelievable! No-one who should have known of the existence of George Morris’s medals had either seen or knew they were existence, which would still be the case had it not been for Michelle Soper and her Arts Theatre colleagues’ enthusiasm to see them reunited with the rightful owner.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Note: ** 1046 Lt-Colonel Hugh Amuri Robinson, DSO, MC, ED***, (mid) – Divisional Cavalry, 18th Battalion & 2oth Armoured Regt, 2-NZEF; British Commonwealth Occupation Force (J-FORCE, Japan).

Sam Robinson’s father, Lt-Col. (later Brigadier) Hugh Amuri Robinson, DSO, MC (m.i.d), ED*** was born in New Plymouth on 29 Sep 1912. A farmhand, he and embarked with the First Echelon, serving continuously until the war ended. Lt-Col. Robinson began his military service as a territorial soldier with the Wellington East Coast Mounted Rifles. His notable career as a citizen soldier first came to the fore as a young Lieutenant serving in the Divisional Cavalry (his first love) in Greece when he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in Dec 1941. Lt-Col. Robinson transferred to NZ Armoured Corps in Oct 1942 and served with both the 18th and 19th Armoured Regiments. He then became the Commander of the 20th NZ Armoured Regiment where he distinguished himself with his leadership and innovation during the final months of the campaign in Italy, particularly during the crossing the River Po for which he was awarded the DSO in April 1945. Lt Col Robinson remained as CO of the 20th NZ Armoured Regiment garrisoned in the vicinity of Trieste until October 1945. Upon his return to New Zealand, Lt-Col Robinson returned to life on the land and farming at Waipukurau. His continued service as a member of the Territorial Forces resulted in his eventual promotion to Brigadier.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My thanks to Michelle and her colleagues at the Khandallah Arts Theatre for initiating the return of these medals. The Robinson family are truly grateful and proud to have been entrusted with George Morris’s medals on his family’s behalf. Thanks also to Lt-Cdr. (Rtd) Rick Howland (Wgtn) who was of great assistance interpreting George Morris’s service record that only a highly experienced ‘old salt’ was capable of deciphering. Last and crucially, Mike Stanley’s sterling research work has been instrumental in pulling the threads of this case together.

The reunited medal tally is now 434.