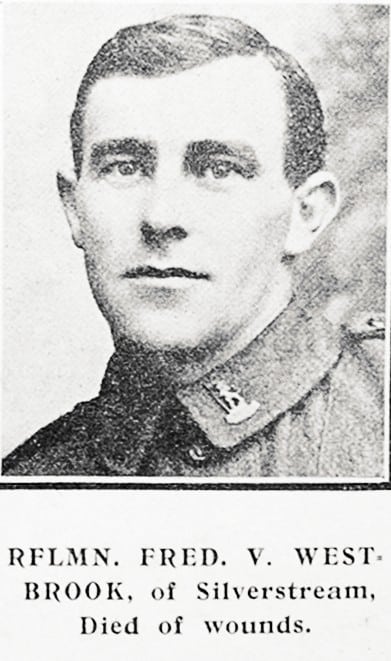

55268 ~ FREDERICK VICTOR WESTBROOK

The Wellington RSA clubrooms had their genesis at 290 Lambton Quay on 28 April 1916 where it remained for almost three decades before the financial health of the NZRSA headquarters and Wellington branch (co-located) allowed the purchase of a new premises in Victoria Street in 1944. A further three decades here came to an end in 1975 when the RSA national headquarters and the Wellington RSA Branch separated to establish their own city locations. The headquarters had bought a couple of floors in a multi-story building in Willis Street (the current Anzac House) and the Wellington RSA relocated into the old Nestlé building in Ghuznee Street. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a declining membership eventually forced the Wellington RSA to call time on its Ghuznee Street clubrooms in the early 2000s. No longer could they financially sustain a central city location which had also proved to be more facility than was required for its membership. The move to a less salubrious suburban house in Karori soon proved to be a well founded decision that fully met the needs of its diminished membership. Throughout this succession of moves, the Wellington RSA’s collection of memorabilia had grown over the ebbs and flows of the club’s popularity. That it had waned over the last two or three decades demonstrated a trend that smaller in the future was likely to be a more sustainable option countrywide.

The RSA of years gone by had memberships made up of predominantly of Returned personnel that had an entrenched camaraderie born from mutual experiences hatched during both World Wars – most would do anything for the other. The Club was considered a ‘second home’ by many where the welfare support comprehensive and the reputation of the RSA was one to be held up with pride. Men were proud to be part of the organisation and so when it came to death, many left their medals and wartime mementos they had gathered, to their RSA in perpetuity. It also became a convenient repository for medals that had been found, most frequently after an Anzac Day parade and the after-match function. Others turned up in Rest Homes after a veteran’s death or in odd places where a veteran had died in either tragic (accidents/suicides) or other deprived circumstances.

Many of these medals made there way into the custody of the Wellington RSA whilst others had been left by widows or family members of deceased Veterans saddled with the dialema of what to do with their spouse/relatives medals after their death, particularly if there were no children to pass them on to? It was these types of circumstances that the NZRSA was presented with that caused clubs to become informal repositories for unwanted and unclaimed medals – the most comfortable path of least resistance when faced with this problem was to ‘give them to the RSA.’ Widows and families who consciously made a decision to leave medals in the RSA’s care, did so in the belief that the ex-service community could be trusted to do the honourable thing of taking perpetual care of these donations. Descendants could then happily shed themselves of any on-going responsibility believing they had ‘done the right thing’ by their Veteran.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Wellington RSA in its previous city premises had had little difficulty in accommodating medal and memorabilia donations however when the decision was made to move to suburban Karori, taking the nearly 90 years worth of accumulated medals and memorabilia with them was out of the question. Ironically, the move to a former Karori domestic residence for their new clubroom was just the type of building from which RSA clubs had sprung after the First World War – was this back to the future? Whilst the smaller building met the needs of its membership, the Karori clubroom had little wall or storage space with which to display and/or accommodate the collection that had previously graced the walls of its former commodious central city locations. Added to this was the Executive’s natural concern for the on-going security required for such items. Quite apart from these aspects, the medals being all of First World War vintage and although named, the recipients were well beyond the living memory of the membership. The absence of records to identify exactly what, when or from whom items had been received just did not exist. During their later years at Willis Street, the medals had gradually been consigned to various types of storage without expert curatorial oversight and so were in danger of having their neglect prolonged. In short the medals held by the Wellington RSA had become a liability and so, after the memorabilia had been suitably distributed, the medals were retained pending a final decision on their disposal.

The RSA Executive under guidance of the then Club Secretary, Lt.Col (Rtd) John Mills RNZIR made the decision to divest itself of responsibility for the medals. They decided that in the first instance all medals would be offered back to the descendant families and that the offer would remain open for as long as was considered practicable (about 6 months). This was duly done via advertisements in the Wellington newspapers and editions of the RSA Review. Names of all recipients whose medals were being held were listed and descendants invited to claim these on production of their proof of their ancestry. I had not seen any of these advertisements but by chance happened to spot the very last advertisement that had been placed in the Review. Having had some previous experience returning Nelson RSA’s WW1 medals to families, I knew full well there was very likely to be a number unclaimed after the claims period expired – and so there were.

I approached John Mills whom I had known in a previous life, and offered MRNZ’s services to research and hopefully return those medals that remained unclaimed. John duly sought the RSA Executive’s concurrence of my proposal which was unanimously affirmed. We were pleased to accept the task and judging by the number of medals that arrived at MRNZ, we will likely be engaged with this project for some considerable time to come.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The subject of this particular post concerns a pair of First World War medals from the Wellington RSA consignment. The medals were sent to Mrs Ellen Goddard / Steffert of Cambridge Terrace, Wellington in 1921. Ellen was the mother of 55268 Rifleman Frederick Victor “Fred” WESTBROOK, her first born child who had died of his wounds in April 1918.

With no records of the medals being deposited with the Wellington RSA, it could be assumed that Fred’s mother, Mrs Ellen Goddard who was the recipient of the medals according to Fred’s file, at some point after 1918 deposited the medals with Wellington RSA as she lived quite close at the time, in Cambridge Terrace. Either that or the medals may have been found possibly at a former residence of Mrs Goddard and handed in to the RSA, as was common practice. It was certainly not unknown for distraught parents who had lost a son to the War, to not want reminders of their son’s death in the house. Many disposed of them forever, sold them or gave them away just to be free from the burden of memory. In 1918 at the time young Fred was overseas, Ellen Goddard was residing at 88 Clyde Quay (now Oriental Parade) directly across the road from the Boat Harbour, in Wellington Central.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Westbrooks of Hampshire

The Westbrooks can trace their ancestry in the family seat of Hampshire back to the 1600s in this area with relative ease, as little had changed in nearly 400 years. Fred Westbrook’s grandparents were Joseph WESTBROOK (1841-1913) from Preston Candover in Hampshire, and Harriet NICHOLSON (1843-1889) from Nutley, also in Hampshire. Joseph was the youngest of six siblings born at Preston Candover to George and Mary Westbrook, only four of whom survived beyond the age of 10 years – Jane, James, Charles and Mary Westwood. By 1861, Joseph who was by then 20 years of age, and the only sibling remaining at home working with his parents, George and Mary Westbrook, Fred’s great-grandparents. The Westbrook family lived on the Oxford Road in the village of Nutley and comprised George (50) and Mary (45), Joseph’s sister Ann (15) who was a Domestic Servant while the youngest Westwood sibling Eliza (10) was still at school.

In November 1862, Joseph Westbrook had married Harriet NICHOLSON (1843-1889) at Basingstoke, Harriet being a native of Nutley. For the next ten years the Joseph and Harriet’s family grew by four children from five births, namely Jane (1863), Thomas (1864-1864), Henry George (1866), William (1867), Martha (1871) and Sarah Ann Westbrook (1873).

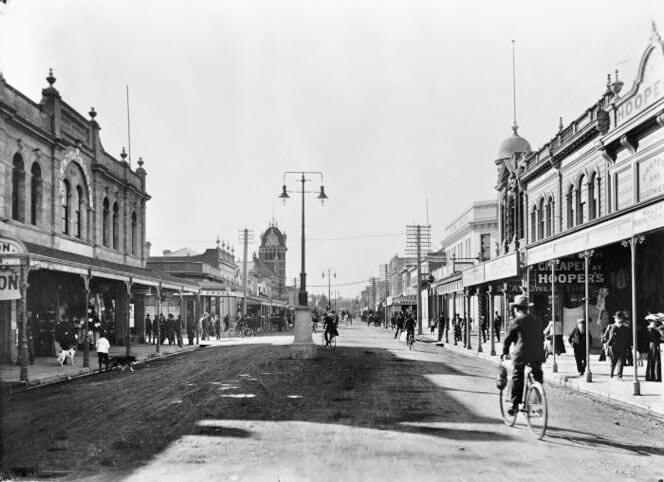

With the main British railway network largely completed, and companies looking further a field for new projects, an outbreak of rural unrest in Britain encouraged many farm labouring Britons to undertake the long and sometimes difficult sea voyage to New Zealand. The Westbrooks were keen to take advantage of a NZ Government offer of cheap fares for immigration to NZ. In 1869 Julius Vogel had become the Colonial Treasurer in Premier William Fox’s New Zealand government. In June 1870 Vogel unveiled the “Vogel Plan”, the most ambitious public works and assisted-immigration programme in New Zealand’s history. The equivalent of $5 billion in today’s term was to be spent on assisted (government-subsidised) immigration and on building or improving infrastructure, including the telegraph network, roads, public buildings and port facilities. Its centre piece was a promise to build more than 1000 miles (1600 km) of railway in nine years.

To realise the ambitions of Vogel’s Plan, government embarked on a program of mass immigration for labourers and agricultural workers among others. It was anticipated the resulting influx of settlers into newly created districts would not only stimulate economic growth but quickly swamp the local Maori population who were hitherto been and seen to be a threat to immigrants as the New Zealand Land Wars had officially concluded less than four years previously. Vogel also believed that employment of Maori with a Pakeha workforce on public works schemes would hasten the integration of Maori into the European economy.

The 1870s was also a decade of dramatic demographic change. The government would assist 100,000 migrants to come to New Zealand, the great majority of them British and Irish. The colony’s European population soared from 256,000 in 1871 to 490,000 ten years later, dwarfing a Maori population of fewer than 50,000. These migrants were among the chief beneficiaries of Julius Vogel’s public works revolution. They settled in cities that were now profitably linked to their hinterlands, in the new towns that sprouted along the rail routes, and in newly accessible rural regions that were becoming part of the productive economy.

By the mid-1870s the government was offering assisted passage from Britain without any work obligations. Many disgruntled navvies broke their contracts and drifted into farming, urban jobs or gold-prospecting. British recruitment was soon abandoned; from now on navvies would be recruited locally.

On the 21st of January 1874, at a cost of £58.00 (then = NZ$580; today = $5,800.00), Joseph Westbrook (33), wife Harriet (31), Jane (10), Henry William (4), Martha (20 and baby Sara Ann (6 mths) left the dock at Southampton aboard the SV Wennington under Captain John McAvoy, for New Zealand, never to return. Ninety eight days later, the Wennington and its 29 migrant families entered the heads of Nicholson Harbour, aka Wellington Harbour / Port Nicholson, on 28 April 1874.

Note: SV (Sail Vessel) Wenninton was a full-rigged, iron, 3-masted ship built by the Lune Shipbuilding Company and launched in March 1865 for Wilson & Co., Liverpool. On the 9th January 1878 the Wennington, under the command of Capt. Sterwood, sailed from Samarang, Indonesia, bound for Cork or Falmouth, with a crew of 18, one passenger and 1,151 tons of sugar in baskets. She was last seen aground in the Bali Straits on the 30th January 1878. Capt. Sterwood sent a telegram that the vessel had been got off and was uninjured. The ship continued on her voyage however was never seen again, lost with all nineteen people aboard. Read more at Wrecksite: https://wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?164668

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Westbrook family settled in the Masterton area of the Wairarapa and within months, an already pregnant Harriet gave birth to Sarah Ann Westbrook (1874-1874) who regrettably did not survive beyond a few months. Three further children followed – Ellen and Mary Westbrook were twins, both born on 25 July 1875, and their brother Joseph Jnr in 1877. The youngest twin Mary died at the age of five on 3 March, 1880.

Ellen Westbrook / Goddard / Steffert

After a limited schooling, Ellen Westbrook followed the well worn path of employment most young working class girls took and went into Domestic Service (washing, cleaning, cooking etc) for a well-to-do family who could afford servants to look after their every need and want. Ellen was employed in the household of Heinrich Christian STEFFERT, a native of Schleswig Germany together with his wife Elizabeth, nee PIKE (1847-1892) who came from Mangaroa in the Hutt. The Steffert’s at that time had four children of their own, the eldest being Augustus William Steffert born at Masterton in 1869.

On the day before her sixteenth birthday, the 24th of July 1891, Ellen Westbrook gave birth to a baby boy whom she named Frederick Victor WESTBROOK. While little “Fred/Freddie’s” father remains un-named to this day, it was clear Ellen would need help through what appeared to be an indiscretion. But five months prior to Freddie’s birth, Ellen had married 21 year old Augustus Frederick GODDARD [II] (1868-1961) in the Masterton Registry Office on 21 Feb 1892. Augustus was an Englishman from Barking in Romford, Essex and had been named after his father, Augustus Frederick Goddard [I] as was common practice for the time. Ellen gave birth to Augustus Frederick Goddard (III) in 1892. His father’s occupation was listed on his son’s birth certificate as “Gentleman” so clearly Augustus [II] had come from a family of some means and therefore, being also of legal age (21), he could ensure a facade of propriety existed for his underage bride and child. The “Goddards” took up residence in Queen Street Masterton and from their union, two biological children resulted – Freddie’s half-brother, Augustus Frederick GODDARD [III] (1892-1960) was born at Kiripini, Masterton, and a half-sister, Ivy May (Goddard) HEMMINGSEN (1902-1983), would be born ten years later at Featherston.

The father of Freddie remained unknown. Whether Freddie’s first name was indicative of one that his natural father bore could be a clue. Being a popular first name of the day, it would be difficult to make a case for paternity on the strength of that alone. Had Ellen and Augustus F. Goddard’s marriage been one of benevolent convenience, or was it purely to put the face of propriety on an elicit relationship, theirs or the result perhaps of a trist Ellen had had that had resulted in Freddie’s unplanned birth? Being a servant in the household of Heinrich (Henry) Steffert, it can also not be ruled out that Ellen had become enamoured with a family member, or indeed willingly or otherwise, coerced into a relationship with a fellow staff member and that Goddard had stepped in as a responsible man was apt to do – one can only speculate in the absence of hard evidence. I suspect Ellen was aware she was about to have Augustus’s child and so their marriage was hastened.

What did become clear was that sometime between the birth of Augustus Goddard [III] in 1892, and 1896, his father Augustus (II) had decamped to Westland. Augustus (II) is shown in the 1896 Electoral Roll as being a resident of Brougham Street in Westport and a Miner, whilst Ellen had remained in Masterton. Another Goddard family member, Henry and wife Mary, were residents of Fern Flat in the Upper Buller. Henry being a Miner may have been the catalyst for Augustus (II) to try his hand at mining.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Whatever the case, Ellen Goddard’s marriage to Augustus F. Goddard [II] did not last. As the end of the century approached, Ellen was alone in Masterton with Freddie and Augustus (II) when yet another gentleman named Augustus came into her life! As if one “Augustus” in Ellen’s was not enough, along came Henry Steffert’s eldest son Augustus William Steffert, known to all as “Augie”. Coincidentally, Augie was the same age as Augustus F. Goddard [II] but whether or not they had known each other prior to Goddard’s marriage to Ellen is unknown but Augie appears in the Electoral Roll at the same address as her, Freddie and baby Augustus Frederick Goddard [III]. Augie was born in Featherson, the eldest of four surviving Steffert children from seven births. He would later inherit six step-siblings when his father Heinrich re-married the widow Mary JENSEN in 1902.

Exactly what Ellen and Augustus F. Goddard (II)’s situation was is unclear. Whist there was no evidence of formal separation or divorce it appears the arrangement of living with Augie Steffert was that of a “Boarder” who in time suplanted husband Augustus Goddard. In 1901 Ellen (21) was again with child and no doubt keen not to invite any scuttlebutt, left Masterton with Augie (20) to live in an isolated area of the Wairarapa known as Whitimanuka in rural Featherston, about 15 km NE of Martinborough along the Ruamahnga River. In 1902 Ellen gave birth to Freddie’s half-sister, Ivy May. Whilst Ellen remained legally married to Goddard, she could not arbitrarily change the child’s surname and so both Augustus (II) and Ivy remained as Goddards. It should be noted however that the 1896 Electoral Roll for Wairarapa shows Ellen and Augie reading as for a married couple: “Ellen Steffert, Whitimanuka – married, and Augustus William Steffert of Masterton – labourer, although one could read several meanings into this combination. On the strength of researched evidence their situation was clearly one of semi-permanence at this time. Since Ellen had turned 21 in 1896, they could with some confidence represent themselves as ‘Mr and Mrs Steffert’ whilst not being legally married. Having a young family also added a degree of credibility to their assumed marital status. It was also obvious that Augustus F. Goddard (II) was now completely out of the picture.

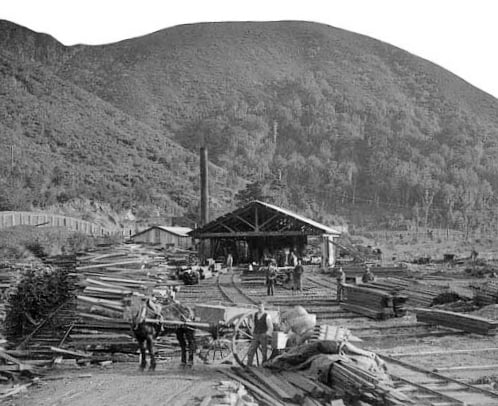

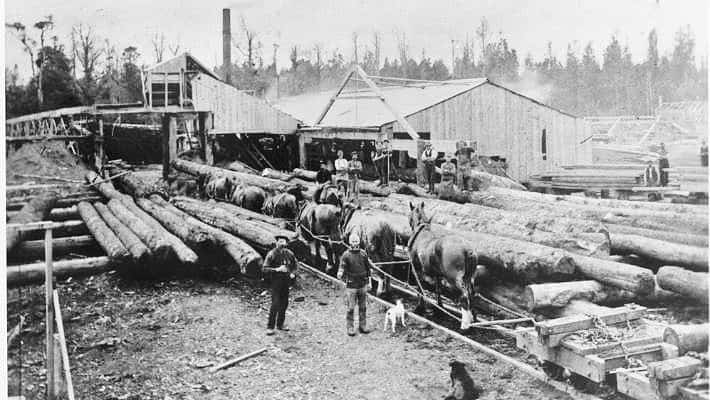

Augie Steffert had been employed as a Labourer at the Whitimanuka sawmill whilst living in the ‘stix’ but following Ivy’s birth, they decided their remoteness served no good purpose as young Freddie who was fast approaching nine years of age, would need access to schooling of a level greater than Whitimanuka could offer. Augustus (III) still a babe in arms and the newly arrived Ivy would also benefit from their mothers access to medical help and assistance. The “Stefferts” moved back into Masterton and took up residence once more in Queen Street, Augie taking on labouring work nearby.

By 1911, Augie Steffert’s employment had changed to that of a Driver – of both horse drawn and motorised vehicles in Wellington. The Stefferts moved once again from Masterton to a residence at 6 Malcolm Lane in Thorndon. By this time, Freddie Westbrook being almost 20 years of age, had left home and gone west to work on farms in the Hutt. He settled into a position as a Shearer for employer Ted (Edward) Swainson, a Stockman who hailed from Pahiatua and whose property was situated in Whiteman’s Valley at Silverstream.

The War clouds gather

Nervousness and apprehension pervaded the New Zealand populace throughout 1912 and 1913 as they read of the deteriorating instability of Europe, and Britain’s sabre rattling. new Zealander’s faced the dim prospect of the seeming inevitability of war, one we would undoubtedly be drawn into as a loyal member of the Empire. It was not long before national registration of employable male manpower between the ages of 17 and 60 was drawn up, not only for military potential service but also in preparation to allocate resources to maintain the country’s industry and infrastructure should NZ become a target. As the country battened down and reduced their outgoings, Augie’s driving job dried up and he was again given to labouring in Wellington at anything going. This had also necessitated another move by 1914, to 151 Adelaide Road in Newtown.

When the call eventually came for volunteers to enlist in the NZEF for service overseas, there was no shortage of takers. Augie was exempted on the basis of his young family and being sole provider. For Ellen’s son Freddie Westbrook, his employment as a Shearer had been keeping him busy without much time to think of military service so he just boxed on with labouring jobs between shearing, drenching and dagging seasons. Freddie was quite comfortable for the time being in his small workers dwelling in the Valley Road at Silverstream from which he could visit his mother in the city with relative ease.

For New Zealand the war began in earnest with the Landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. The newspapers carried endless coverage of the day by day situation at the front together and later, ever lengthening columns of the casualties. In 1916, Ellen Goddard and Augie Steffert (as yet still unmarried) were quite well settled at 33 Cambridge Terrace in Wellington central, Augie having returned to driving again as many motor vehicles rapidly replaced the four legged transporters of people and goods.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rifleman Frederick V. Westbrook

The Military Service Act passed on 1st August 1916 empowered the government to call up any man of military age (20-45, in 1915 it had been 20-40) for active service abroad, subject to passing a medical examination, and any appeals process. Compulsion to be registered on the national roll had not produced the number of voluntary reinforcements to keep pace casualties taken out of action, and those caused by medical exemptions from enlistment, and a quantity who evaded their duty when the casualty rolls were made public. The Act was the instrument to commence conscription (compulsory military service) whereby men were drawn by ballot to serve overseas. Failure to respond to the ballot, if not successfully appealed, threatened men with fines, imprisonment in addition to overseas service. Whilst Freddie had been registered on the National Manpower roll, understandably he was in no particular hurry to go to war but at 25 years of age, he knew he would be a sitter once conscription commenced in October 1916. Fortunately for him he had chosen to volunteer prior to the implementation date and so would not bear the stigma of being shamed into serving or worse, be accused of shirking! Fred had been added to the roll of the 5th (Wellington) Regiment Reserve, subject to a medical fitness clearance.

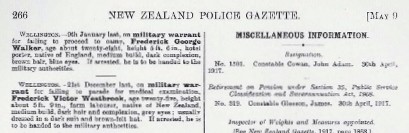

As volunteer numbers began to taper, Fred Westbrook received his marching orders to mobilise in early 1917. A pre-enlistment medical check was the first official requirement to be conducted by an Area Medical Board of which there were several convened around the Wellington province, as required. For some unknown reason Fred had failed to attend his medical check appointment Army had arranged for him. This was a serious oversight in the eyes of the Army. As a consequence, an Arrest Warrant was issued by the military authorities which was published in the “Police Gazette” – the ‘boys in blue’ were on the lookout for Fred as were the Military Police.

Police Gazette – May, 1917 WELLINGTON – “21 December last, on military warrant for failing to parade for medical examination. Frederick Victor Westbrook, age twenty-five, height about 5ft. 9in., farm labourer, native of New Zealand, medium build, dark hair and complexion, grey eyes; usually dressed in a dark suit and brown-felt hat. If arrested, he is to be handed to the military authorities.“

It is not known whether Fred had failed to get the notification to attend his medical board or had simply overlooked it. His residence in 1914 was listed as Valley Road, Hutt so clearly he had a known address but if away up in Whiteman’s Valley, sometimes for days or weeks at a time, he would not be able to get to a post office for his any mail and therefore would possibly be unaware he was wanted. Whiteman’s Valley in 1917 was fairly wild country but whatever the case, failure to attend an enlistment medical board amounted to breaking the law. On this there was no compromise. Fred’s file carries no further evidence of any repercussions so presumably he was able to satisfy his masters with the reasons for his previous non-attendance. On 23 May 1917, Fred attended the medical board in Wellington and was passed as “A–FIT” , he was ready to start training for war!

On the same day, twenty five year old 55268 Private Frederick Victor Westbrook of the 5th (Wellington) Regiment Reserve presented himself at Trentham Camp and was attested for war service. He was assigned to the Infantry and committed by law to serve in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) for the duration of the war.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Featherston Training Camp

All soldiers entered the Army at Trentham Camp where they stayed for a week or so taking additional medical tests, receiving inoculations, and issues of basic clothing and equipment to get them through their week at Trentham. From here the reinforcements would be taken to Featherston Camp to start their basic soldier training in earnest. No doubt Fred would have felt somewhat up-beat in returning to his former hometown and people he knew.

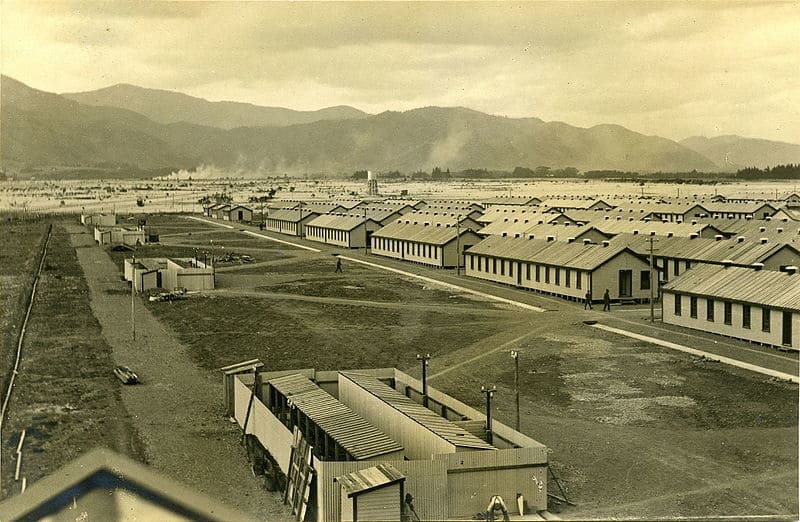

On 24 January 1916, New Zealand’s largest World War One training camp had been opened at Featherston especially to train Reinforcement drafts. Built on both sides of the main road between the Featherston township and the Tauherenikau River, the Featherston Military Training Camp was used to train intakes of up to 2000 men in infantry and mounted riflemen skills. More advanced training and field skills were also taught at Featherston and other smaller camps in the Wairarapa. Each numbered reinforcement draft trained as a group, broken down into companies (infantry) or squadrons (mounted rifles). The soldiers were housed in the company groups, each hutment housing about 50 men, while tents usually housed eight to ten men. There were eight large dining halls at Featherston MTC which could cater for the hutment population at one sitting.

Infantry (foot soldiers) made up the largest part of the Army. They practised marching, arms drill, shooting, trench-digging, bayonet fighting, and attack and defence work. They were trained to take their place as a replacement Riflemen in one of the NZ Rifle Brigade’s four rifle battalions. Training at Featherston was for most branches of the Army except Medical staff (trained at Awapuni Racecourse, Palmerston North) and Pioneer companies (labourers – initially at Avondale Camp and Narrow Neck Military Camp, adjacent to Fort Takapuna). Pioneers were not front-line fighting units but a military labour force trained and organised to work on engineering duties, digging trenches, building roads and railways, and taking on any other logistical tasks deemed necessary. This was essential and dangerous work that was often carried out under fire and the initial roll given to the NZ (Maori) Pioneer battalion. There was a riding school for mounted rifles and artillery, which needed trained horsemen. Mounted rifle troops had long treks, and the artillery did live firing near Morison’s Bush. The men marched or rode to the training grounds each morning and afternoon.

The training concluded with a route march from the Featherston Camp, over the Rimutaka Hill and back to Trentham – 38 kilometres over a period of two days and three nights. The men carried fighting kit (rifle, ammunition, small pack, rations and waterbottle) and carried out a mock attack in the Mangaroa Hills. This was not only a test of their personal fitness and endurance but also part of an on-going unofficial competition between successive Reinforcement intakes to see which could better the time of the fastest to date. The first march began on 23 September 1915 (7th Reinforcements), starting a routine in which almost every reinforcement draft (1000-2000 soldiers) marched over two nights and three days back to Trentham Camp, weeks before embarking for the front. Over 30,000 infantry marched over the Rimutaka Hill – the last reinforcement draft in April 1918.

After almost exactly eight weeks to the day, the training of the 28th Reinforcements was completed on 26 July. All medical and dental standards had been met, uniform and kit had been issued, and all trainees had taken home leave before their embarkation date to say final their farewells.

Last goodbyes

Fred Westbrook had stayed with his mother and Augie at their latest residence, 23 Cambridge Terrace in Wellington whilst he also bid his step-siblings Augustus and Ivy a fond farewell, the last he would see of them all until after the war.

The 28th Reinforcements were split into two drafts to travel on two ships. The first draft had departed two weeks earlier on 14 July aboard HMNZT 89 Waitemata. Pte Westbrook was in the second draft which embarked on to the HMNZT 90 Ulimaroa on 26 July 1917 and set sail for Plymouth, England the following day. Ulimaroa arrived at Plymouth on 24 September, the men disembarked and entrained to Bulford, Wiltshire where the NZEF’s Sling Camp was established on the Salisbury Plain. Here they were assigned to the 4th Reserve Battalion, Canterbury Infantry Battalion for the next few days while they found their land-legs again and orientated themselves to the Camp. On 27 September Private Westbrook became Rifleman Westbrook when he was transferred from the Wellington Regiment Reserve to the NZ Rifle Brigades’s Reserve Depot at Brocton Camp, about 150 kms to the north of Sling Camp.

On 23 October, the newest Reinforcements to join the Rifle Brigade’s battalions were dispatched across the Channel to Etaples, France. They were accommodated in the Depot Camp at the NZ Infantry & General Battalion Depot whilst they prepared to be moved to the Front. On 02 Nov 1917, Rflm Westbrook joined the 3rd Rifle Brigade in the field. He was posted to ‘D’ Company of 2 Rifles, which in full was, 2nd (Wellington) Battalion, 3rd NZ Rifle Brigade (2/3NZRB).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Battle of Ancre, 1918

The NZ Division had undergone a series of forced marches during the advance until they were concentrated at Hédauville during Spring Offensive. Facing a numerically superior German force intent on forcing the Allies back, the Battle of Ancre was fought during the months of March and April 1917. As the NZ Brigades advanced eastward towards Ancre from the vicinity of Colincamps, unit by unit, they slowly closed the gap on Ancre in the face of heavy artillery and machine gun opposition from a substantial German opposition. On the night of 4/5 April, the 1st NZ Brigade was withdrawn from the centre of the Divisional Sector and replaced by the 2nd NZ Brigade. With a frontage of around 3000 meters from One Tree Hill on their right flank, through La Signy Farm in the centre, to Hébuterne on the left, the NZ Rifle Battalions were positioned in extended line with 1 Rifles on the left, 4 Rifles in the centre, 3 Rifles on the right and the four companies of 2 Rifles (incl Rflm Westbrook with ‘D’ Company) positioned centre rear of the Brigade. 2 Rifles was tasked as the Brigade Reserve and was co-located with the Brigade’s other support elements – logistics, ammunition, medical, signals, engineers etc.

At 0500 on 5 April, an intense enemy bombardment opened on the front line of the NZ Division and continued for three hours over the whole area. Heavy shelling reached all the way back to Colincamps which was a mile behind 2 Brigade’s front line. Two of the Rifle Battalion’s HQs located in cellars in Colincamps narrowly survived after a pounding with 12” shells. Soon after 0800 the German’s mounted an infantry attack with the object of penetrating the Allied front line to reach Colincamps. The first attack was completely repulsed after coming within 25 meters of the Brigade’s main trench line but was successfully beaten back by 3 and 4 Rifles. The companies of 4 Rifles took the worst of this with around 50 of their men killed.

At 1000 hours the attack was repeated. A small 4 Rifles garrison of 14 men in the most advanced trench east of La Signy Farm was overwhelmed and attempts were also made to attack 4 Rifles frontage. Once the smoke haze cleared, this attack was repelled with very effective MG and rifle fire. No significant progress by the enemy was made for the remainder of the day. Reliable estimates put the enemy casualties opposite the Rifles’ frontage as not less than 500 while the NZ Division had sustained altogether 150 casualties, mostly walking cases.

On the 6th of April the 3rd Rifles again advanced pushed forward on the right flank of the 2nd Brigade. The enemy seeing what was developing summoned reinforcements in the form of additional infantry (particularly machine gunners) and more heavy artillery. The result was dire for 2 Rifles (the Brigade Reserve) and support element in vicinity of Colincamps, which took the brunt of the artillery barrage. During this pounding Rflm Westbrook was hit several times by artillery shell shrapnel. The 2 Rifles battalion commander Major Pow was also wounded and command passed to Major Jardine, M.C. In the evening, the NZ Division retaliated with a devastating artillery barrage of its own which annihilated an attempted counter-attack.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fred’s medals

To locate a descendent of Fred Westbrook was not too difficult. When I worked back through his family tree, it was clear a good proportion of Fred’s generation and some of those prior had migrated to the Nelson – Tasman area. That had been good background but to get as near to Fred’s immediate family I had to follow his mother in the first instance. That became quite a task, not only because of her earlier relationship and determining when and where that had ceased, but also because she remained unmarried and had alternated between Goddard and Steffert in Wellington, particularly during her early days there. It was difficult to determine if she was still married or had reverted to Goddard as her husband did not always appear in the Electoral Rolls. With few formal records and no census taken during the Second World War years, it was impossible to reach any firm conclusions at this time.

For all that, I followed the addresses on Fred’s file which had indicated little, other than that his mother had not moved from Wellington but had managed to cause the NZEF authorities considerable confusion in trying to trace her. Addresses at 188 Vivian Street (as Ellen Goddard), 23 and 55 Cambridge Terrace (as E. Steffert), 88 Roxburugh Street (as E. Steffert), and Clyde Quay (twice as E. Goddard) did not make it easy to forward Fred’s memorial Plaque & Scroll or his medals once they became available in 1921. At one point with all of his mother’s contact addresses crossed out, his uncle Joseph Westbrook Jnr had been listed as a point of contact, his address being: J. Westbrook, c/o Ariki, Murchison .

After continuing to follow Ellen Goddard’a trail, eventually her listings were consistently as Ellen Steffert, her name at long last being legally confirmed in June 1935 by her marriage to Augie Steffert. Mrs Ellen Steffert died in Wellington nine years later on 15 August 1944 at the age of 69. Her husband Augie Steffert died in Porirua Hospital in 1959 at the age of 89. Both are buried in the Karori Cemetery.

The tragedy of Neville Steffert’s loss was that he was one of the 1000 New Zealanders who were killed between mid-June and the beginning of August 1917 in this, Haig’s Third Battle of Ypres, in which he determined that La Basse-Ville was t be a decoy attack only. The one bright spot for the Wellington Regiment was that the attacks on La Basse-Ville had netted the Regiment its first Victoria Cross, awarded to Cpl Leslie Andrew WILTON, a Signaller NCO with B Company of Neville Steffert’s battalion.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Motueka connection

As a result of this trail I was able to trace Ellen Steffert /Goddard/Westbrook’s family tree, working in reverse until I found two siblings born after her, Mary WESTBROOK in 1875 at Masterton (died 1881) and Joseph WESTBROOK Jnr at Masterton in 1877, later a farmer at Maruia near Murchison. Joseph died in Nelson aged 80 in 1958.

As Joseph Westbrook was the last and therefore youngest sibling of Ellen’s, I elected to follow Joseph’s family first to try and locate a living descendant for two reasons: first, being a male Westbrook, Joseph (hopefully) had a male heir thereby preserving the Westbrook name. This could put the medals into the hands of a son who continued to carry the Westbrook name. In due course, the same process would be repeated by subsequent family custodians until there was no longer any male heir. It is at this point that the medals could go to a female family member but the significance of the original family name tends to be lost. That being the case the medals could ultimately wind up in the hands of a family member who might not have the slightest idea who the Westbrook family was with the result, medals get disposed of and leave a family’s custody usually forever.

Joseph Westbrook had married Susan McGILL and a family of four boys resulted: Ralph Joseph (1913-1988), Kenneth Andrew (1918-1990), Jake (1909-1931) and Leo Gordon Westbrook (1913-1929). I started with Ralph Joseph and his wife Muriel Gwendoline BIGGS who was also born in Murchison, and had died at Wakefield. This led me to believe there was a good chance of children still being in the area. Further research produced the name of Ralph and Muriel’s two sons: David Ralph Westbrook and John Hubert Westbrook.

As luck would have it David Westbrook was listed in the phone directory, a nearby resident of Stoke. I decided to seek David’s advice and recommendation for the most appropriate Westbrook descendant to be the custodian of Fred’s medals. After meeting with David (a former banking exec) and his wife to discuss this, David was unequivocal – “contact my brother John in Motueka, he has military service and would be most interested in looking after these.” When I did get in touch with John, I quickly realised why David had been keen for his brother to have the medals.

Another Veteran in the family…

John Hubert Westbrook known universally as “Westie” is a Vietnam veteran! Originally from Motueka, in 1965 Westie was working at the Firestone Tyre factory in Papanui, Christchurch together with his good mate Michael Ernest Bradfield, also from Mot. National Service was something that tended to hang over the heads of every male aged between 19 and 21 during the 1960s and 70s as one of the necessary evils the government of NZ had inflicted on young men in order to obliterate their social lives. Having been entered into the national register of eligible trainees as was required by law, ballots were conducted annually at first and then quarterly, once a man turned 20. Birth dates were drawn according to a government quota of persons required to undergo basic military skills training in order for the country to maintain a pool of servicemen should they be needed.

Westie and Mike were due to be balloted not long after the Battle of Long Tan (16 July 1965) in South Vietnam, a battle which had involved both Australian infantry and the New Zealand Artillery countering a numerically superior Vietcong force. The battle had received widespread coverage in the newspapers and on television not only because of the casualties, but because of the heroic rescue of the trapped Australian infantry by Armoured Corps personnel together with the support of NZ’s 161 Battery. The TV coverage of this had fired Westie and Mike’s enthusiasm and together they decided to opt for voluntary National Service and then have a shot at getting a tour of duty in South Vietnam. By volunteering they figured they could cut out the years of obligation in one hit – job done!

Westie and Mike voluntarily enlisted in 1966 to start their 14 weeks of basic soldier indoctrination and orientation at Waiouru. This was followed by a period of Corps specific training at the home base of the Corps each soldier had chosen to join. Westie and Mike had both opted for the Royal New Zealand Artillery.

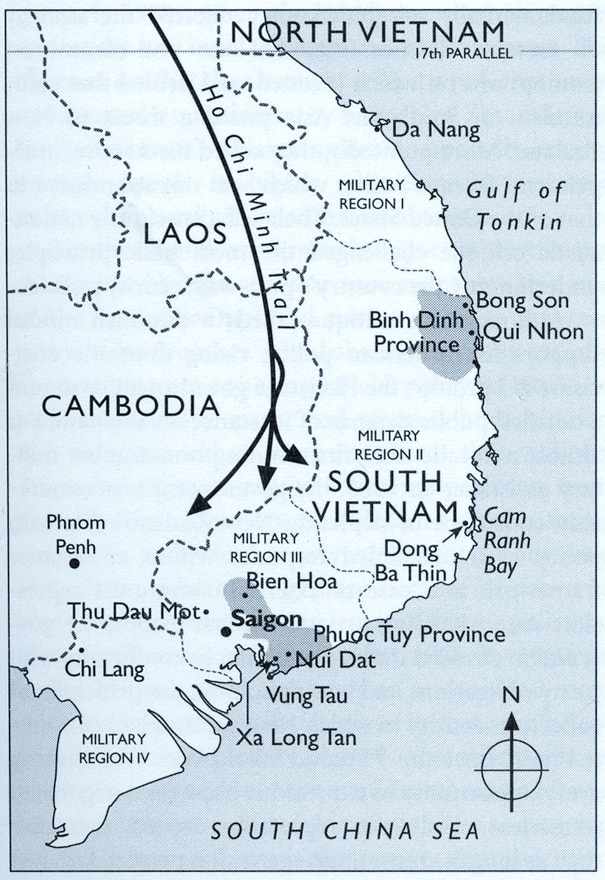

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gunners Westbrook and Bradfield arrived at Bien Hoa towards the end of 1968 where they bought up to speed on their operational duties by the 161 Battery training team. They were to be employed as Radio Operators for Forward Observation (FO) parties and would be assigned to the 1st Australian Task Force headquarters at Nui Dat, for deployment with Infantry battalions as required. Forward Observation is an artillery function and the reason Westie and Mike were attached to infantry units. Because artillery is an indirect fire weapon system, the guns are rarely in line-of-sight of their target which are often located miles away.

In South Vietnam, the artillery of NZ and Australia operated from a series of Fire Support Bases (FSB) sighted to prevent incursions across the South Vietnamese border and proximate to the Communist Viet Cong regular and irregular forces likely lines of advance, this being dictated largely by the mountainous terrain over a large part of the country. A FSB is a fortified position where the guns of a battery are well defended and protected. These are sometimes dug into the ground to lower their above ground profile whilst being surrounded with sandbag bunding to protect the men from small arms fire and shrapnel in the event of ground or mortar attack. The FO party (normally an Artillery officer, a radio operator and one other soldier) is the ‘eyes of the guns’ by sending target locations and where necessary corrections, to the fall of shot. As a radio operator, Gnr Westbrook was required to accurately relay the Forward Observation Officer’s (FOO) directions (and corrections) to the Battery Commander at the FSB in charge of the fire mission.

Note: ** Infantry formations also have organic FOOs in the shape of a Mortar Fire Controller (MFC). MFC’s are usually NCOs.

As an FO radio op, Gnr Westbrook was attached to two different Australian infantry battalions for FO duties during his tour of duty with the 3rd Australian Regiment (3RAR) and the 9th Royal Australian Regiment (9RAR). On 19 January 1968, shortly after his arrival in Vietnam, Westie got a huge wake-up call during a ground attack – he was wounded in the hand. A gunshot wound to his right wrist whilst not life threatening, certainly got his attention and effectively put him out of action for several weeks. Gnr Westbrook recovered in due course and went on to complete his tour of duty in South Vietnam without further personal injury. Both he and the now Lance Bombardier Mike Bradfield returned to NZ in December 1969 which also signalled the completion of their national military service obligation under the terms of the Defence Act. After two and half years in the Army they had achieved what they set out to do, gained a lot of life lessons and experiences along the way, as well as developing a healthy appreciation of the dangers of living life on a two-way rifle range.

For their service, both “Westie” and Mike were awarded the Vietnam Medal and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal with Clasp “60–”. Once back in New Zealand, Westie decided against a return to Firestone Tyres and returned to his hometown of Motueka. After a long leave period he went back to work on the land, going into business as a fencing contractor which he continued in until he retired.

In July 2002, thirty three years after Westie and Mike had returned from Vietnam, they were both awarded a third medal – the NZ Operational Service Medal which was instituted to recognise all New Zealand service personnel who have deploy overseas on active service since 3rd September 1945. The NZOSM is only issued once after a person’s first operational deployment – there are no clasps.

Having a direct descendant of Fred Westbrook’s family to take ownership of the medals was immensely pleasing as it meant they would be owned by someone who still carried the Westbrook surname, something that is not always possible when the recipient is female or a family has undergone many alterations to its structure. It was both a pleasure and honour to return Frederick Victor Westbrook’s medals to his grand nephew John “Westie” Westbrook. All things being equal, they will not be lost to the Westbrook family ever again.