16/236 ~ EDWARD THOMPSON

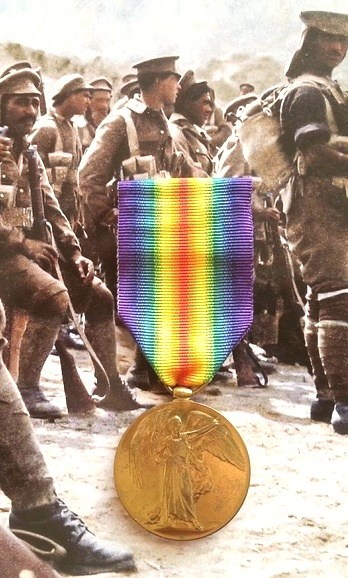

A First World War Victory Medal found more than 40 years ago in the deceased estate of an Upper Hutt pensioner’s father, has been returned to a daughter of Private Edward Thompson, NZ (Maori) Pioneer Battalion.

In 2020 Sylvia F., an Avalon, Upper Hutt pensioner contacted me regarding a Victory Medal named to 16/236 Private E. THOMPSON N.Z.E.F. As is often the case with medals sent to MRNZ, Sylvia found this medal over 40 years ago as she was sorting through her deceased father’s personal belongings. When or how her father had come by the medal Sylvia has no idea. But she did believe it would likely be important to someone “Thompson” whoever that might be, and so had intended to do some research of Pte. Thompson’s family to see if she could return it herself. Time however has been Sylvia’s enemy as it is for most of us, and the opportunity to get into her project never quite eventuated. She did however consciously safeguard the medal for all those years with her honourable intent always in mind.

I said to Sylvia that we would be pleased to help her out and on being made aware of her advanced years, would work on the case as quickly as possible to find a descendant. One aspect Sylvia was quite adamant about was that she wanted to return the medal personally. To that end she was not prepared to send the medal to MRNZ even though it had no ribbon and would likely be in need of a clean before it was handed over. Normally I would not agree to researching any medal that we are not holding (for the reasons detailed on our website) but gave in to Sylvia’s wishes on this occasion and agreed to take on the case without the medal.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

16/236 Private Edward Thompson – 1st NZ Native (Maori) Contingent

Edward “Eddie” Thompson (Maori translation = Eruera Tamihana) was born in October 1885 at Pirinoa near the Turanginui River in the Southern Wairarapa, near Lake Ferry. His father, Rakai THOMPSON (Tamihana) of Ngati Kahungunu and Ngati-Hinepare, was a half-caste Bushman, Farm Labourer and Shearer from Gisborne, while his mother, Violet KUI KUI, was a full blood of Ngati Ahuru from the Waikato. The Thompsons had lived on the East Coast both in Wairoa and Gisborne before moving to Pirinoa in Southern Wairarapa, early in the 1880s to take up bush clearance work to create farmland.

Edward Thompson, or Eru, Eddie or Tam as he was known, had grown up in the Wairarapa and by the time he reached his early twenty’s had moved to the Scandinavian influenced bush settlement town at Dannevirke, a hub for milling timber to build Palmerston North. Whilst Eddie remained mobile around the Wairarapa on various work contracts, his parents Rakai and Violet moved from Pirinoa to Greytown prior to 1900s before migrating further south over the Rimutaka Hill to a home at 145 Jackson Street in Petone. Home during the twilight of Rakai and Violet’s lives would eventually be Tokoroa where Rakai worked for some years as a driver until he retired.

Signing up for war

At the time registrations were being taken for men of fighting age to join the NZEF, Eddie was working as a Labourer in between shearing seasons, in Martinborough for a Mr Daniel Riddiford (1814-1875), an English pioneer run-holder who in 1839, had been appointed the emigration agent for the New Zealand Company’s first settlement in New Zealand at New Plymouth. Riddiford had occupied the southern Wairarapa property known as the Orongorongo Station in 1846, some 7,000 acres between the Wainuiomata and Mukamuka Rivers. Later he took an option on an East Coast run of 30,000 acres, no doubt one of the reasons Eddie had regular work on the East Coast as well as at Martinborough. Nothing however was going to stop him from joining his mates on the ‘trip of a lifetime’ once the word was out and attempted to enlist for war service in 1914.

Maori denied the right to fight …

Despite the willingness of many Maori to fight, Imperial policy of the day opposed the idea of indigenous peoples fighting and the use of weapons against European forces in what was seen as a ‘white man’s war’. In September 1914 Prime Minister William Massey announced that the British government had accepted the offer of a 200-strong Native Contingent for service in Egypt. Following another New Zealand request, the force increased to 500 men, with the balance to be deployed for occupation duties in German Samoa. Maori leadership also argued that the Contingent should not be split but all stay together and in their respective tribal groups.

Recruitment of the Contingent began in late September under the direction of a Maori Recruitment Committee (MRC) consisting of the MPs for the four Maori seats – Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hiroa), Maui Pomare, Apirana Ngata and Tame Parata – and the MP for Gisborne, Sir James Carroll.

Many young Maori men responded with enthusiasm to the recruitment drive. Some communities volunteered in large numbers, others did not contribute at all. This reflected the experiences of different tribes during the New Zealand Wars of the 19th century. Tribes who had been neutral or allies of the Crown, such as Te Arawa, Ngati Porou and Ngapuhi, were more likely to volunteer for the war. Those tribes that had fought the Crown and suffered land confiscation, such as the Taranaki, Tainui and Tuhoe peoples, produced few volunteers.

Despite repeated requests made to Major-General Alexander Godley by New Zealand Minister of Defence James Allen and determined Maori MPs Apirana Ngata and Maui Pomare who argued forcefully for sending Maori into action, they were denied. This strident Imperial stance resulted in the Native Contingent not being deployed to Gallipoli with the first invasion force in April 1915. Instead, it was decided the Contingent should be kept in reserve and so was placed on garrison duty on the island of Malta, where further training would be undertaken.

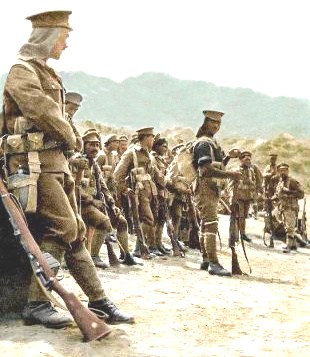

As the ANZAC body count mounted at Gallipoli to unanticipated levels, desperation and some convincing tough talk, finally led to agreement for the 461-man Contingent on Malta to be landed on Gallipoli. The NZ Government view had also done an about face once it became apparent that Indian and African troops would be taking part in the conflict. The Native Contingent arrived at Anzac Cove on 3 July 1915 where they joined with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and deployed as dismounted infantry soldiers. Their impact was immediate and significant, and their ferocity in the fight unequalled. Many fell in the next six months but never their spirits or will to take the battle to the Turk. Of the 477 men of the Contingent who landed on Gallipoli on 3 July, only two officers and 132 other ranks survived – less than 28 %!

Following the withdrawal of what was left of the Contingent from Gallipoli on December 15, a period of rest spent on Lemnos preceded their departure from the Dardenelles on Christmas Eve, 1915. Four days after arriving back at Alexandria, the Contingent were on their way south to Camp Moascar at Ismailia. Here the Contingent was effectively broken up with the remaining soldiers being interspersed with the troops of the Otago Battalion who had been adapted into the pioneer role after suffering many casualties at Gallipoli. With the arrival of the 2nd Maori Contingent and two squadrons of Otago Mounted Rifles, the NZ Pioneer Battalion was officially formed on 4 March 1916 prior to their embarkation on HMNZT Canada for France on the 9th of April.

The role of a pioneer battalion was to provide unskilled labour to construct roads, bridges, fieldworks, camps, camouflage screens under the direction of the Field Engineers. The battalion was organised into four companies, each 200 strong. Companies comprised four platoons – two Maori and two Pakeha, 50 men in each platoon, per General Godley’s instruction. Other Maori soldiers were encouraged to transfer to the Pioneer Battalion, but many chose to stay in the battalions in which they had enlisted. Later, Pacific Island contingent personnel were added into the ranks of the battalion.

It was not until October 1st, 1917 that the unit’s name was officially changed to New Zealand (Maori) Pioneer Battalion, the only unit that returned to New Zealand as a battalion.

Sources:

Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; Whitiki! Whiti! Whiti! E! Maori in the First World War by Monty Soutar

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

1st NZ Native Contingent (NZNC)

16/236 Private Edward Thompson was 24 years and 9 months of age when he was attested for military service at the Avondale Military Camp in Auckland on 15 November 1914. While most of the Main Body troops were being trained in and around Trentham at various temporary camps, Maori recruits were assembling at Avondale for their training.

Pte. Thompson embarked with the reminder of the Contingent on HMNZT 20 Warrimoo on 14 February 1915, joining with the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). The convoy of 10 NZ ships with 8000 men, 1100 horses and support equipment departed Wellington bound for the West Australian port of Albany. Here the NZ convoy would link up with its Australian equivalent and the two would travel together under armed escort to England. The Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war in 1914 altered the convoys route from it original destination in England, to Suez in Egypt.

After passing through the Suez Canal to the Port of Alexandria, the men disembarked and were entrained to Zeitoun, about ten kilometers north of Cairo, where the NZEF established a base camp to for training before committing its troops to combat.

The security of the Suez Canal was the first action NZ troops would be involved in. It was also the site of NZ’s first battle casualty of the First World War on 5 Feb 1915, Pte. William Ham of the Canterbury Battalion, from Ngatimoti near Motueka. Following the failed naval action in the Dardenelle Straits, attention had shifted to the the Ottoman forces massing on the Gallipoli Peninsula. This then became the focus of attention by the British High Command who decided the NZ and Australian Divisions, together with British and Indian forces would land and seize the Peninsula. Gallipoli’s terrain also negated the use of the NZ and Australian mounted units and so these were employed as dismounted infantry riflemen.

Gallipoli, July 1915

The landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 were mildly successful however by May, the casualty rate among the ANZACs was staggeringly high. Their foothold was tenuous at best and in real danger of faltering. Reinforcements were required smartly if the ANZACs were to gain any initiative to press home continued attacks up the steep slopes of Gallipoli. The Native Contingent on Malta being the only realistic option for immediate support was returned to Egypt in preparation to join the fight on the Peninsula.

The Contingent embarked at Alexandria for the Dardanelles on 21 July, just three weeks before the now infamous assault on Chunuk Bair. Stepping ashore at Anzac Cove on 3 July, the Contingent was rushed into the battle to be used as a shock tactic, to put the fear of god into ‘Johnny Turk’ in order to salvage the situation. This the Maori soldiers did with uncompromising aggression and ferocity. Many a Turk must have rued the day they had been born when confronted with a Maori soldier in the dead of night who was in full war cry during an attack with nothing but lust for the blood of the Turks on his mind.

Pte. Eddie Thompson of B Company was with the Contingent from the start and took part in a number of the actions aimed at seizing the high ground on the peninsula, and driving the Ottoman’s back. See-sawing confrontations seemed endless with much of the fighting done at night over perilous terrain, largely uphill. Attack and counter-attack was the nature of the battle, often at close quarters, the distance between some forward trenches/posts being within hand-thrown bombing (grenade) range. After eleven months of attempting to oust the Ottomans from Gallipoli, the ANZACs were withdrawn from the Peninsula, the New Zealanders departing under cover of darkness over three nights in December 1915, without a single life lost. For Pte. Thompson, his time on Gallipoli had been punctuated by periods of hospitalisation, either aboard an off-shore Hospital Ship, at the Australian Field Hospital on Mudros, or back in a Malta hospital. A range of health conditions affected, some he arrived with including the recurrence of ulcerated varicose veins on his right leg which continued to plaque him for the remainder of his service.

In August 1915, the diminished numbers of the 1st NZ Native Contingent were split up among the other four NZ battalions until the withdrawal from Gallipolli was completed. The ANZACs returned to Egypt to re-group before embarking for France and a completely different style of warfare on the Western Front – trench warfare.

By the time the 1st NZNC arrived back in Zeitoun, the 2nd NZ Native Contingent had arrived in Egypt and a 3rd NZ Native Contingent was due to leave New Zealand in Feb 1916. Once all three had assembled in Egypt, their numbers were supplemented with men from the Otago Mounted Rifles to bring the resulting unit up to battalion strength (around 960 officers and men). This new unit would specialise in the construction and maintenance of roads and tracks, bridges, laying duckboard tracks across the pulverised battle grounds, building fortifications, and defence works such erecting barb wiring entanglements and obstacles. These men would constitute the New Zealand Pioneer Battalion.

In March, the Pioneer Battalion was dispatched to Moascar on the Suez Canal in preparation for embarkation to France. Pte. Thompson however was hospitalised yet again for his leg veins problem however would be recovered sufficiently when the unit embarked.

France, 1916

The battalion embarked at Port Said in June and on arriving at the Etaples Depot Camp, settled in to await their deployment to Boulogne in about five weeks. During this period, Pte. Thompson managed to incur the wrath of his CO for failing to comply with an order given by an NCO ( considered a serious offence on Active Service). For the offence he was sentenced to 21 days of Field Punishment No 2. which involved having fetters tied around his ankles to limit his movement to a shuffle and handcuffs placed about his wrists. Hard labour and a loss of pay was also part of the sentence of FP No.2. Aside from this, Eddie Thompson’s only other noted indiscretion in his file was his failure to parade at 07.30 hours for a Fatigue Duty in August 1918. For this he received two days Confinement to Barracks (CB).

The next ten months were spent shadowing the New Zealand Division supporting the initial battles of Flers-Courcelette, the Somme, Morval, Transloy, and the big one – the Battle of Messines on 7 June 1917. Men of the NZ Native Contingent were heavily committed in support as the Allies advanced towards the Hindenburg Line.

On 24 June 1917, Pte. Thompson was hospitalised suffering the effects of Chlorine Gas poisoning after the bombardment of an area they were moving through. The use of poisonous gas on the Western Front was first employed by the Germans on April 22, 1915. At 5 p.m. on that day a wave of asphyxiating gas released from cylinders embedded in the ground by German specialist troops smothered the Allied line on the northern end of the Ypres salient, causing panic and a struggle to survive this new type of weapon.

So devastatingly effective was the gas in producing mass casualties (incapacitated as opposed to death), it was soon put into artillery shells and mortar bombs to be fired over much greater ranges. One could be come a casualty by the gas drifting on the wind, or by its residual effects from trapped under frozen ground until the warmth of the sun can re-releases it, or that which is trapped in below ground structures. Fortunately for Pte. Thompson his exposure was not too severe and within a few days he was passed fit to return to the battalion.

In the four years Eddie Thompson spent at both Gallipoli and on the Western Front, apart from being affected by the poisonous gas (classified as a ‘wounding’), he sustained only one actual bullet wound. A gun-shot to his right buttock on 4 August 1917 was again fortunately not severe, necessitating just one week in a field hospital. He was again hospitalised for Influenza in July 1918 which at the time was sweeping the northern hemisphere with a vengeance, killing thousands and making even more perilously ill for lengthy periods. After a short stint at No.7 Convalescent Camp in Boulogne and No.6 Convalescent Camp at Etaples, Pte. Thompson’s recovery was such that he was sent back into the field with the NZ Pioneer Battalion for eleven more months. The lasting effects of the recurrent varicose ulcers on his leg however would ultimately affect Pte. Thompson’s medical grading and fitness for war service after his discharge from the NZEF.

Finally in August 1918, Pte. Thompson was withdrawn from the field, given 14 days leave and then sent to the Discharge Depot at Torquay for demobilization and a medical assessment in preparation to return to NZ. Eddie left Liverpool aboard the SS Oxfordshire on 3 Feb 1919, and arrived in Auckland on 4 Feb 1919. All things considered, apart from being somewhat debilitated as were most returning soldiers who had been living in conditions of sustained privation, he was not too much the worse for wear – except for the leg!

Eddie was given immediate leave which he took back in Greytown however while at home he was required to present to the Greytown medical facility for on-going out patient treatment for his veins and other contracted ailments. Placed before another Army Medical Board in June 1919, Eddie was deemed to be “no longer fit for war service” on account of the varicose veins in his right leg. Pte. Eddie Thompson was officially discharged from the NZEF on 28 July 1919.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Eddie had returned to Greytown and his parents house, they having re-located from Pirinoa in the south. In due course he began working again as a labourer, shearer and busman. This eventually took him up to the East Coast back to Gisborne and Wairoa, eventually finishing up living in Freeman’s Bay area of Auckland. It was here that Edward Thompson died of heart failure on 27 October 1944 at the age of 59, and was buried in the Soldiers’ Section of the Waikumete Cemetery in Henderson, Auckland.

Medals: 1914/15 Star, War Medal, 1914-18, Victory medal + Anzac [Gallipoli] Commemorative Medallion & Lapel Badge

Service overseas: 3 years 55 days

Total NZEF Service: 4 years 283 days

‘Te Hokowhitu a Tu’

‘the 70 twice-told warriors of the War God’

Anzac Medallion gives up a clue

Eddie Thompson’s lineage is hard to define since his and his first wife’s deaths resulted in a number of children that were unknown to each other. The search for a Thompson descendant in South Canterbury was initiated as a result of an annotation of his military file that showed someone had claimed Eddie’s entitlement to an Anzac (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion on 9 November 2004. The medallion to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Gallipoli landings on 25 April 1915, was created in 1967 and available to all NZ and Australia Gallipoli veteran survivors, or the next of kin of survivors who had subsequently been killed or died after the Gallipoli campaign. Unfortunately, a descendant is not entitled to claim the miniature Lapel Badge of the medallion as these were a prerogative of living Gallipoli veterans only.

Searching the local community electoral rolls and census, I found there had been Thompson’s living at Pleasant Point and in South Canterbury area around Timaru as late as 1981 (the end of Ancestry’s records).

Leonard Te Hiko Tamihana Thompson, known as “Tami”, was the eldest son of Eddie and Violet Thompson, born in June 1934. Tami’s marriage to wife Beverley “Pixie” ROBERTS (1947-2009) of Waipawa resulted an amalgamation of five children. Tami had worked for some years in his younger days in the Putaruru sawmill until moving south and gaining farm and labouring work. He settled in Timaru working at the Port of Timaru as a Watersider until he retired, then moved out to Pleasant Point, about 20 kilometers north-west of Timaru.

Taking a punt that there may still be Thompsons connected to this family in the region, a check with NZ Defence Personnel Archives and Medals could only tell me (in order to comply with the Privacy Act) the plaque had been sent to Pleasant Point, South Canterbury in 2004. It had been almost 20 years since the medallion had been claimed, but a search of electoral records of Pleasant Point and the surrounding rural regions resulted in a handful of Thompson names.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mike makes a break thru’

With other pressing cases I needed to attend to, I had handed over the research of this case to our southern MRNZ research specialist Mike Stanley, to continue efforts to make contact with the Thompson family. Mike worked through the Thompson names we could contact and got lucky with the only one listed in Fairlie, Vanessa Thompson. Vanessa was one of Eddie Thompson’s grand-daughters whose last address in the area had been at Fairlie however when Mike couldn’t, he eventually found her on Facebook. She was no longer in Fairlie but had also moved to Australia and fortunately for us, was in touch with her other siblings over there.

Vanessa told Mike that after Beverley’s death in 2009, the remaining adult children had stayed in the area as Tami was getting fairly elderly at that time. After Tami passed away on 17 April 2014 at the age of 79, the family still in the area dispersed with three brothers – Marlin, Willie and Robert aka”Bart” in Australia, Louise to Christchurch, while Vanessa remained living (until now) at Fairlie.

Eldest son Marlin Thompson had inherited the Anzac Medallion his father had claimed in 2004. After speaking with both Marlin and Willie re the proposed medal arrangements, there was some doubt they would be able met in Wellington all at the same time and so suggested Louise in Christchurch act on behalf of the family to receive the medal from Sylvia. Sylvia was happy with that arrangement and so we planed for the handover in Wellington a couple of months hence.

The “best laid plans of mice and men ...” as the old saying goes when a plan fails to come together as it did for this occasion, but not for the want of trying. For us it was something entirely unexpected and unheard of – “COVID-19”- this undid the plan as all domestic and international travel was ruled out for an indeterminate period, and the public generally did not know what to expect next?

Medal laid to rest …

Fortunately Louise was Facebook grouped with her whanau and linked me into this so that we could co-ordinate an alternate plan for Sylvia once the government allowed us to come out of ‘lockdown’ and travel as before. As we all know, that became a protracted situation for the next 18 months or so and scotched any further progress.

By the time the lockdown’s were starting to lift, Sylvia was also on the cusp of having to move from her Tennyson Street home in Avalon to a Wellington retirement home. She had remained adamant in her wish to personally hand over the medal and, if necessary, would arrange for her daughter in Invercargill to drive up to Wellington and back to Christchurch to meet with Louise and handover the medal over, such was her passion to return it personally. Regrettably, time and circumstances again conspired against the plan as New Zealander’s faced the vagaries of yet more ‘lockdowns’.

Finally, Sylvia agreed to send the medal to me so that it could be fitted with a ribbon and pin, which was then sent back to her. She would personally post it to Louise together with her own message included. In the mean time Sylvia had had a telephone conversation with Louise. And so it was done. After 40+ years in Sylvia’s care, the Victory Medal of Private Edward Thompson had finally been returned to his descendant family, grand-daughter Louise Thompson.

Postscript

While talking with Louise, she suggest that another medal of her grandfather’s may have survived and be in the hands of an aunt, Nola Bella Teawhina LANEFEALE (nee Thompson), wife of Togia Lanefale, and sole surviving daughter of Edward and Violet Thompson. A check of this by Louise and myself eventually revealed that as nobody in the family had ever seen Eddie Thompson’s original medals (unsurprising given his short life), ‘Aunty’ Nola had actually purchased a trio of replica First World War medals with which to honour her father and his war service on Anzac Day. This of course begs the question: where are Eddie Thompson’s 1914/15 Star and British War Medal, 1914/18 ? – presumably still out there somewhere in NZ.

Regardless, Louise and her siblings in Australia agreed that ‘Aunty’ Nola was the most appropriate person to be the custodian of the medal as the most senior surviving direct descendant of Eddie Thompson. Sadly ‘Aunty’ passed away in before Anzac Day in April 2022 at the age of 84, and before she could receive the medal. The whanau collectively decided the Victory Medal of Nola’s father should, as a final tribute, be buried with her — and so it was, medal and daughter reunited with father in death.

“magafaoa neke ole atu foki kia lautolu ke o atu mo koe”

Nola Lanefale’s son, and cousin to the Thompson whanau, Ahutoa Lanefale has inherited his mother’s replica medals and will continue to honour the memory and service of 16/236 Private Edward Thompson, 1st NZ Native Contingent, later NZ (Maori) Pioneer Battalion, by wearing these each Anzac Day.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My thanks to Sylvia and her daughter Helen for assisting to get this returned medal project ‘across the line i the face of some unique hurdles along the way. Thanks also to Louise and to Togia Lanefale for the additional material provided for this post.

The reunited medal tally is now 446.

~ Lest We Forget ~