38407 ~ CLARENCE GODFREY EGAN

As students of New Zealand military history are aware, 6/246 Private William Arthur HAM (22) from Ngatimoti in the Tasman district was the first NZEF soldier to die in combat during WW1. The recent sale of his Pte. Ham’s British War Medal 1914-20 on Trade-Me for NZ$7000.00 demonstrated the public appetite – collectors, museums and citizens, for military medals of significance when they come up for sale – read the story here: Pte. W A Ham’s medal sold

As most users of the internet know almost anything can be bought or sold including not just items being bought and sold by individuals, but also by commercial traders. A case in point is the large number of professional traders who deal in coins, medals and militaria. Clayton Ross, a former RNZEME soldier from Motueka, is a man who for many years has loyally supported his local RSA as both a committee member and a welfare representative. Whilst welfare assistance is provided in many forms by NZRSAs, it is subject to the vagaries of available volunteers. Clayton however has preferred to follow up his former committee appointment by providing a personal, long term aftercare service to these veterans in his community. By his commitment to the veterans of the Motueka community, Clayton has established an enduring confidence and genuine relationships with the veterans, many now quite elderly and infirm. It is these men (and women) Clayton has put the most time into, time that few others have available to offer on such a regular basis. For Clayton it has always been a case of veterans first, last and always, above all others.

Clayton has seen the last of the WW1 veterans go from his community and since then his time and energy has gone into the rapidly shrinking group of Second World War veterans. Having seen so many whom he has cared for over the years, pass away in the absence of family or relatives, and with former friends and colleagues having already gone, it is unsurprising that when Clayton sees an item of military memorabilia on the internet that has belonged to a NZ veteran he has known, or is motivated to save, he does something about it.

Medals ‘for sale’

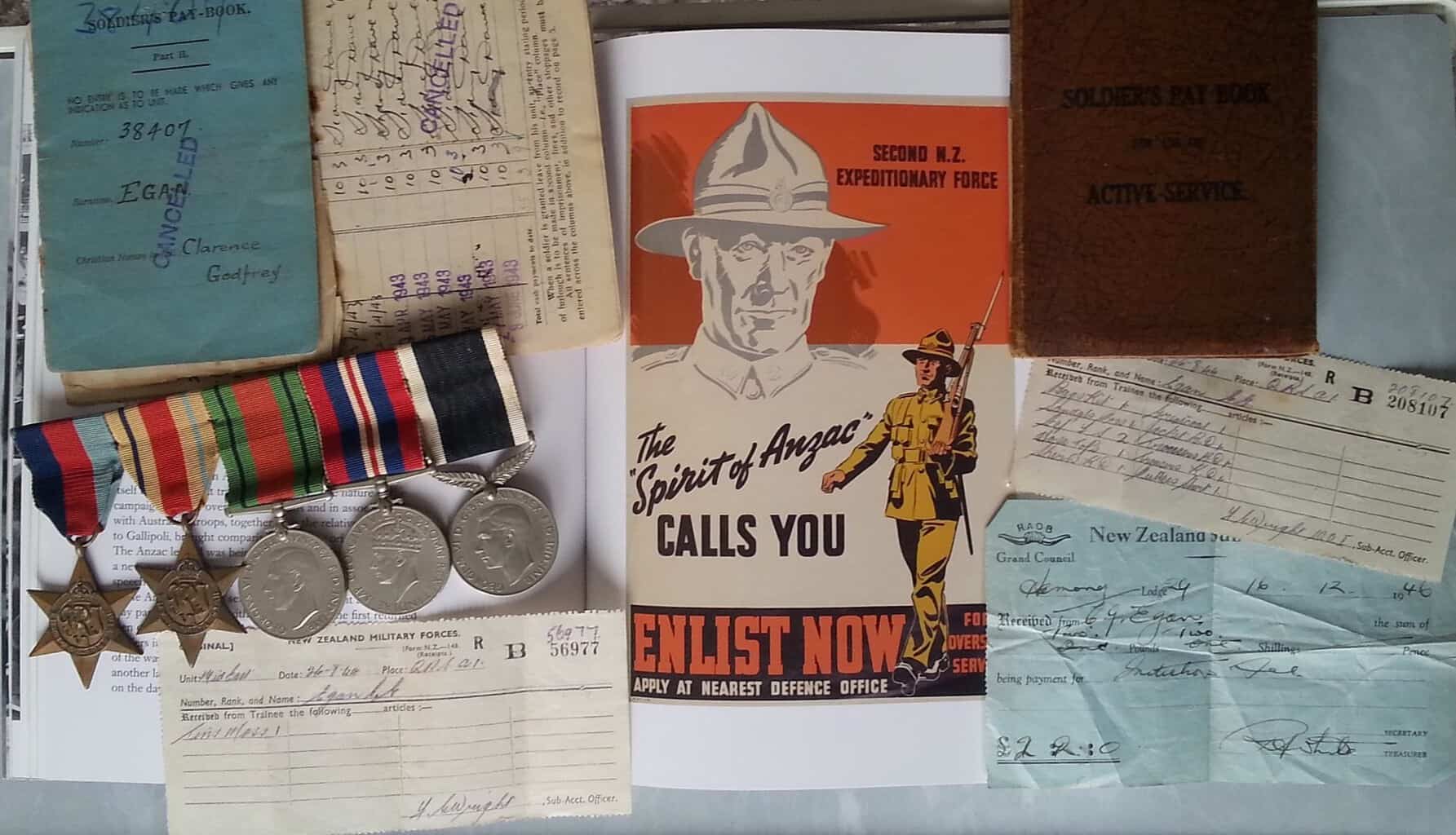

In early 2019 a group of five original Second World War medals plus a Pay Book attributed to a NZ soldier, was posted on a Canada/US military medals trading website called eMedals with the following summary:

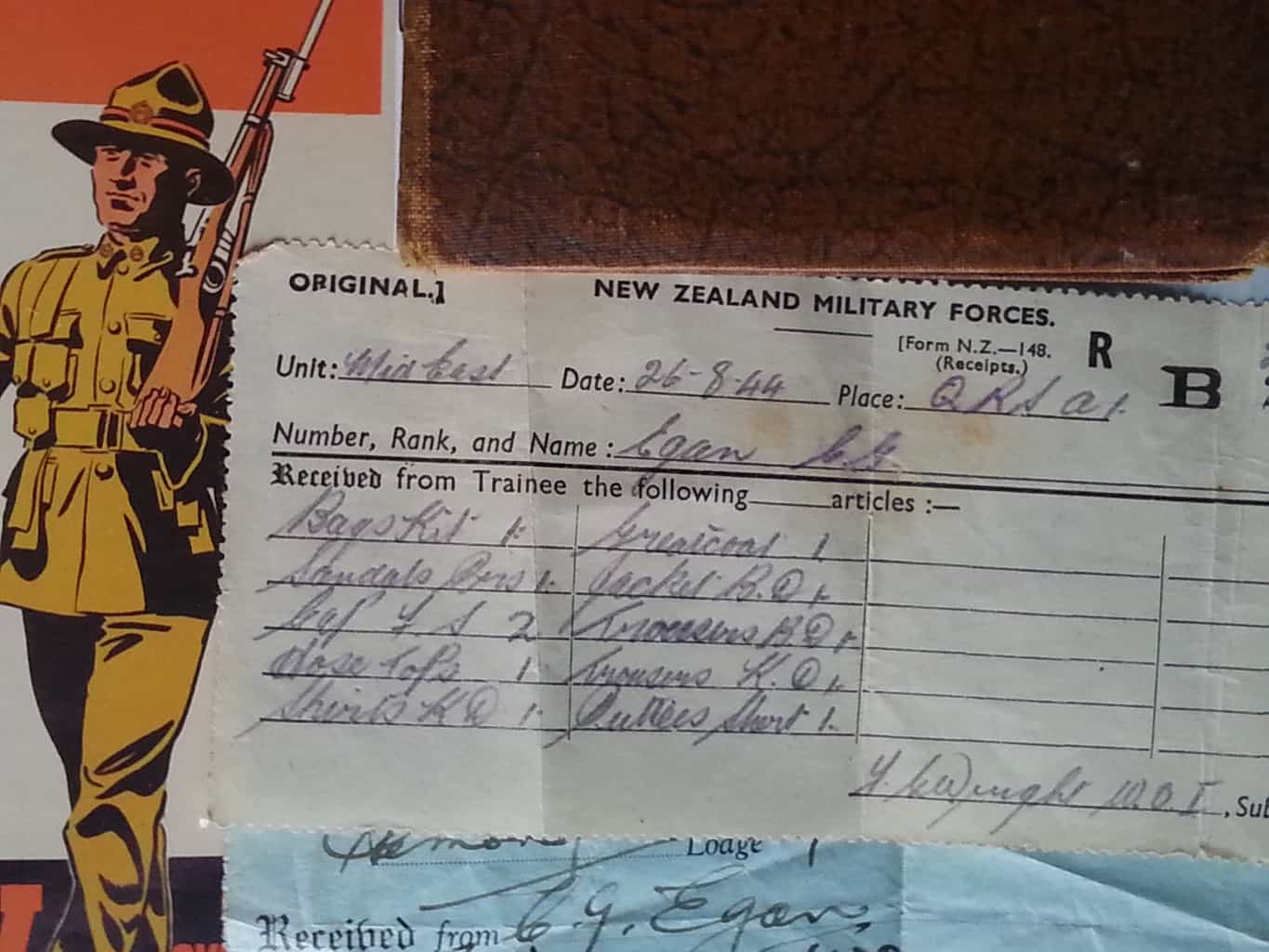

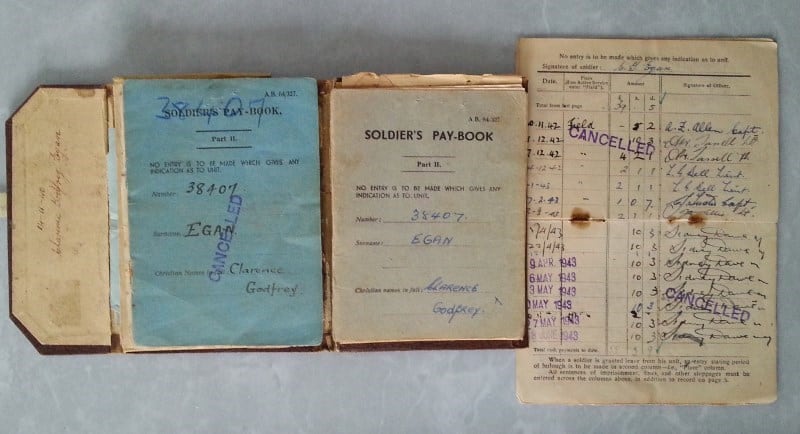

“1939-1945 Star; Africa Star; Defence Medal; War Medal 1939-1945; and New Zealand War Service Medal. Mounted to a suspension with swing bar pin back, as worn by the veteran, spotting and residue in the recessed areas on the Stars from cleaning, light contact, original ribbons, better than very fine. Accompanied by his Soldier’s Pay Book for Use on Active Service (with handwritten entries dated from February 1941 to June 1944, the Pay Book also containing two receipts, an Armed Forces Second Class Free Railway Ticket issued for the period October 9 to November 5, 1944, and a Rules of the King’s Empire Veterans of Auckland booklet, measuring 100 mm (w) x 135 mm (h)).”

Footnote: Clarence Godfrey Egan enlisted for service with the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force (38407) on November 14, 1940, at the age of 42, naming his next-of-kin as his wife, Eileen Muriel Egan of Onehunga. He served with 2NZEF until his return home in late October 1944. For his Second World War service, he was awarded the 1939-1945 Star, the Africa Star, the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939-1945 and the New Zealand War Service Medal.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Oddly enough I had seen these medals in January in the course of one of my regular visits to medal trading websites looking for NZ medals being offered for sale. In April 2019 these same medals and Pay Book appeared again, not on eMedals but on NZ’s own Trade-Me website. Clearly the medals and Pay Book had been purchased (eMedals, 02 Mar 2019) by someone in New Zealand and were being on-sold for profit. The Trade-Me site identified the seller as a Palmerston North resident whom I recognised as a regular medal trader/collector.

The medals themselves were nothing special, an ordinary very original group of five medal (two stars and three circular medals) mounted as worn on a brooch medal bar, in the swing style – tarnished commensurate with their age. The medal group attribution was to 38407 L/Cpl. Clarence Godfrey Egan – 21st mechanical Engineering Company, 2NZEF. The medals were accompanied by two Pay Books and a few receipts.

British campaign medals for Second World War service were issued in their hundreds of thousands. Whilst commonwealth countries such as Australia, Canada and South Africa chose to name the WW2 medals before issue, New Zealand and Britain issued the medals in blank, i.e. they were un-named. Had the Pay Book not accompanied the medals, there would have been no way of knowing to whom the medals belonged. Naming of WW2 medals was not compulsory, the choice to do so was the owners (retrospectively the issue of un-named medals has proven to be a dumb decision by the NZ and UK govt’s of the day, a highly controversial decision at the time, made in the interests of cost saving. That decision continues to have on-going ramifications for the owners of WW2 medals that are lost or are stolen today, proof of ownership if found or recovered by authorities being the biggest headache).

Fortunately the Pay Book gave the medals a degree of legitimate attribution. I say a degree as there is no way of conclusively proving the medals and the Pay Book belonged to the same man, unless the seller was that veteran. The fact the two items were being sold by a reputable dealer (eMedals) and advertised as belonging to the same person was cause for some confidence – for a seller/dealer to be discredited should items be proven not to be “as advertised”, in terms of the potential for the loss of reputation and trust by customers, the result can be catastrophic.

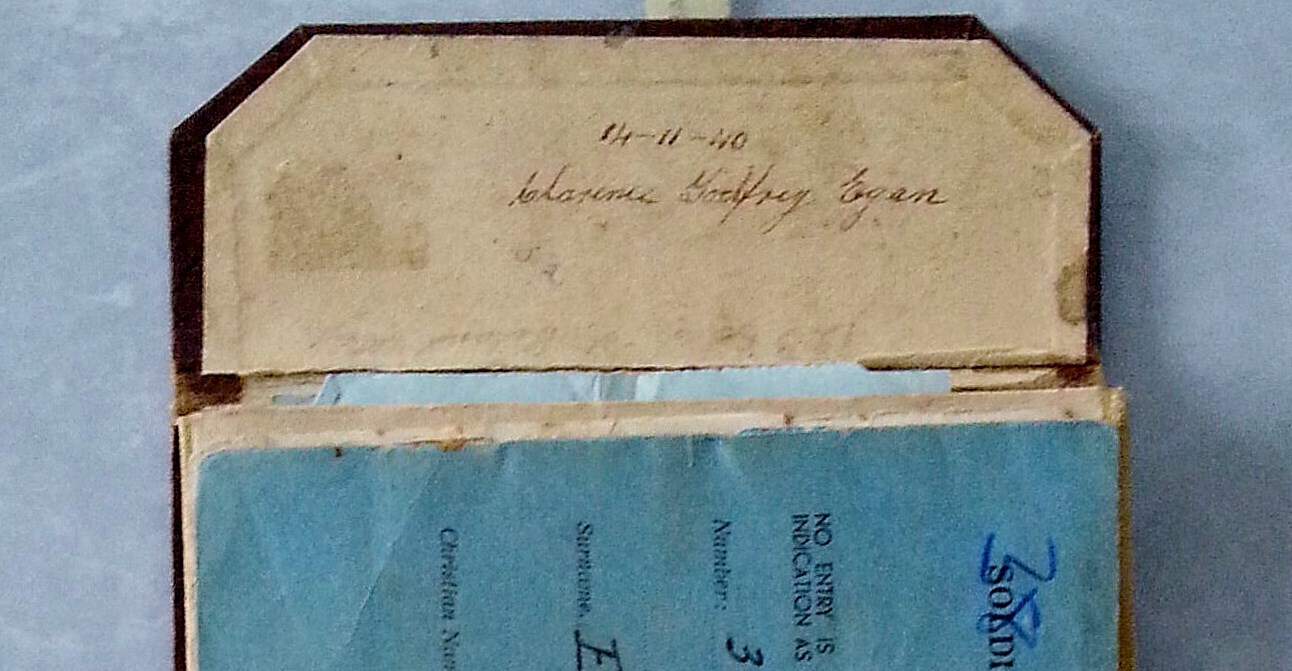

The Pay Book cover was marked inside with a date 14.11.40 and the soldier’s full name, Clarence Godfrey Egan. The individual books inside also contained both his name and service number. These together with his known dates of service, tallied with the locations and dates contained therein.

When Clayton saw the medals he was somewhat irked that they were for sale. He became even more perturbed as questioned the possible reasons for their sale. Surely, he thought, there must have been someone in L/Cpl. Egan’s extended family who would have been only too pleased to have been given an ancestors war medals? Clayton chewed this over for a while – perhaps there wasn’t any family descendants left? The medals seemed to be in very good original condition and he felt sure someone from Clarence Egan’s descendant or extended family could be found to pass them on to – a grandson, grand-daughter, brother, sister, nephew, niece, cousin etc – rather than have them sold on the internet.

In a spur of the moment decision, Clayton paid the “Buy Now” price for the medals and Pay Book with a view to hopefully reuniting them with someone in Clarence Egan’s family – if indeed he had any?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I had only spoken with Clayton a couple of times on the phone and did not know him personally but when he called and told me of the medals and the reason he had bought them – could I find out if Clarence Egan had any family? I was very happy to help with his noble gesture.

The odds of finding family descendants of a WW2 veteran you would think would be much higher than those of WW1 since only half as many years had elapsed and many first generation descendants still being relatively young. WW1 veterans on the other hand have largely died out making their descendant families much harder to find. Once I had looked at the Auckland War Memorial Museum Cenotaph website profile for Clarence Egan, I managed to gather enough information from it without having to request a copy of his military file (WW2 files have not yet been digitised and may only be viewed either at NZ archives, or by paying for the privilege to view on-line).

From the information on the Cenotaph profile page (birth date, place of enlistment, parents, address and occupation, unit and rank, I was able to link this to NZ Censuses and Electoral Rolls to trace Clarence’s movements around NZ. There were also sufficient accessible public records to allow me to construct a good portion of Clarence Egan’s family tree to determine to whom his war medals might go to.

Early days

I pieced the following together: Wellingtonian John EGAN (1860-1943) was labourer who had worked his way from Wellington to the northern Rangitikei around Taihape by 1900. His first recorded census listing shows that he was a waggon driver from Moawhango which is an area 40 km north-east of State Highway No. 1, about midway between Taihape to the south and Waiouru to the north. In September 1896 John married a former Napier girl and then Utiku resident Charlotte “Lottie” JEFFARES (1875-1949) at the church in Utiku (south of Taihape). The couple had eight children, the first three born at Charlotte’s family home in rural Meanee, near Taradale on the outskirts of Napier.

First born was a son, Vincent Joseph (1896-2004) was the first born followed by twins, Clarence Godfrey (1898) and his brother John Leslie “Jackie” Egan (1898-1902) who unfortunately died at the age of 4 years 6 months. Evelyn Jane MINCHIN (1899-1967) followed, and a move back to Taihape saw the birth of Harold Richard (1901-1901) who survived for just 3 months, and their last born Alvera Robina Agnes “Bina” FAZAKERLEY (1902-1987). By 1905 the Egans were living at Ohutu where John ran his own carrying business for the next 20+ years. Ohutu is about 30 kms due east of Taihape in very rough and remote back. By 1930 the Egans had moved into Taihape, John working as a labourer.

Clarence Egan, or “Clarrie” as he was known, was schooled in Taihape. At just sixteen years old when World War 1 began, he was still too young to enlist. He would not be considered for enlistment until he was at least eighteen and not permitted to go overseas anyway until he had turned twenty. As it transpired the Armistice ending the First World War occurred only weeks after his 20th birthday – he had perhaps dodged a bullet ?

Once he left school, Clarence Egan started work initially as a labourer around the Taihape area and then as a sawmill hand at a local mill. Having met a young lady from Auckland in the early 1920s, Clarrie at 25 years of age took the plunge in July 1923 and married 18 year old Eileen Muriel EDLIN (1905-1971) at St Thomas’s in Ponsonby, Auckland. The NZ Herald reported the wedding in its “Social Jottings” column:

NZ HERALD – July 23, 1923

~ Social Jottings.~

WEDDINGS

“The wedding took place at St. Thomas Church, Ponsonby, Auckland, of Miss Eileen Maud (sic) Edlin, eldest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Edlin, of Auckland (late, of Petone), to Mr. Clarence Godfrey Egan, second son of Mr. and Mrs. John Egan, of Ohutu, Taihape. The bride was in a charming frock of ivory white satin and georgette, trimmed with brocade, silver lace, and beads, also pearls. She wore a veil and orange blossom. Miss Kathleen Edlin was chief bridesmaid, and was in white silk with pearl and silver fringe. Misses Beatrice and Harriet Harrington also attended, wearing lavender silk with pearl and silk fringing. Mr. Vincent Egan was the best man, and Mr. Jack Harrington was groomsman.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Shortly after their marriage Clarrie got a job with the Egmont Box Company in Taumaranui. He and Eileen moved to Taumaranui which two of their three children were born (at Taihape) – Vincent Edwin “Vince” Egan (1925) and Helena Alice “Trixie” MacPHERSON (1927). By 1929 Clarrie, Eileen and the two children had moved back to Eileen’s hometown of Auckland, where Clarrie again secured a job as a mill hand. The family settled in Onehunga at 262 Church Street before the arrival of their third child, Mavis Muriel EGAN in 1931.

Clouds of war

By 1937-38 speculation was again rife that another major conflict in Europe would undoubtedly draw New Zealand into a war it did not want. The world had followed the rise of Italian Facism, and Japanese militarism in the 1920s which had resulted in the invasion of China. Nazism under Adolph Hitler and his Nazi Party, reared its ugly head in 1933 as he pursued an aggressive foreign policy. The action taken by Germany on 1st September 1939 was the last straw and our fate became sealed – Germany invaded Poland. The immediate effect for NZ was that Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 Sep 1939. As loyal British subjects, NZ was obliged (expected) to back Britain – where Britain went, so we went meaning New Zealand was also at war. Only twenty years of relative peace had passed since Nov 1918 before the country was yet again beginning to heave under the weight of preparations for war and the dispatch of another generation of young men to a foreign war we were obligated to fight.

New Zealand was committed to supporting Britain with the provision of a Division – three Echelons (contingents) of men, equipment and supporting arms were planned for deployment overseas as the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2 NZEF). Once the First Echelon was fully manned with regular Army soldiers and volunteers (territorial forces), the numbers of volunteers dropped off markedly. The government was concerned there would not be enough men to fill the Second and Third Echelons let alone the reinforcement drafts that would invariably be needed the longer the war went on.

At 41 years of age, Clarence Egan would be unlikely to avoid being called-up for this ‘show’. However, as a married man with dependant children (although nearing their twenties) he was unlikely to be called up immediately.

Younger single men would be conscripted ahead of married, older and family men. Having had almost 20 years in the timber industry, Clarrie Egan was as the saying goes “fit as a buck rat” and had a well developed physic and although lean and wiry, he was strong and agile. He was in the best shape of his life and was ready, willing and able if the call came. Clarrie had his forty first birthday just 24 days after Britain and France declared war on Germany. He had only just missed out on the first war but was not about to miss out on the second. When the call for volunteers came in early 1940, Clarrie, who at the time was working for the PWD (Public Works Department later known as the Ministry of Works) in Auckland, volunteering immediately. Unbeknown to him he would see service overseas much sooner than he had expected.

The Auckland Star – 22 June 1940

CITY RECRUITING.

147 MORE ENLISTMENTS. Enlistments in No. 1 (Auckland) area continue at a steady rate. For the two days up to nine o’clock last night, 147 recruits came forward. Their names are:— C. A. Breeze, E. R. Parkinson, L. M. Deighton, D. H. Freer, L. A. W. Davis, L. A. Waller, T. Fraser, S. V. Griffiths, M. A. C. Paul, A. K. Piatt, H. P. White, V. J. Egan**, A. A. Cook, G. A. J. Smith, C. Shelly, K. R. Jackson, J. E. Ballantine, W. K. Davidson, C. G. Egan, J. C. Lennox etc, etc.

Whilst working for the PWD, Clarrie had gained many skills and in particular was very capable heavy machinery operator e.g. scrapers, rollers, excavators, ‘dozers, shovels and ditchers as well as being a fairly handy general engineer. It was fortuitous timing when Clarrie chose to volunteer for military service. Given his wide range of capabilities, wealth of experience and maturity, he was immediately selected for a new Army unit being assembled.

On 12 November 1940, the day after the 22nd anniversary of the Armistice of WW1, the following appeared in the NZ Herald:

NZ Herald – 12 November 1940:

SPECIAL COMPANY —– ARMY ESTABLISHMENT ——— MECHANICAL ~ EQUIPMENT

A mechanical equipment company, to be known as the 21st Mechanical Equipment Company, New Zealand Engineers, is now being established for overseas service. It will consist of 11 commissioned officers and 250 other ranks, and will be mainly required for excavating work. Most of the men are expected to be drawn from the Public Works Department, which is examining applications before sending selected men on to the Army Department for mobilisation. Included among the men wanted are 178 drivers of mechanical equipment, such as tractors, carry-alls, scrapers, bulldozers, angle-dozers and shovels. It is stated that only men capable of handling these machines should apply as drivers, although vacancies also exist for fitters, welders, carpenters, plumbers, electricians and bricklayers. The first party of Auckland men for the company will leave for Trentham on Thursday. They are:—J. B. Batty. W. G. P. L. Brooks, H. L. Doidge. C. G. Egan, R. C. Fielder, F. Gill, R. Harris, R. Maddox, A. E. Marsh, F. J. Martin, A. A. Moore, L. N. Nankivell. H. C. Partington. T. R. Pihema, R. Polkinghorne, P. G. Reanney, C. J. Reillv, R. H. Richmond, S. Rolleston, L. E. C. Thomas, C. F. Turner, A. J. West, H. Williams, J. A. Young.

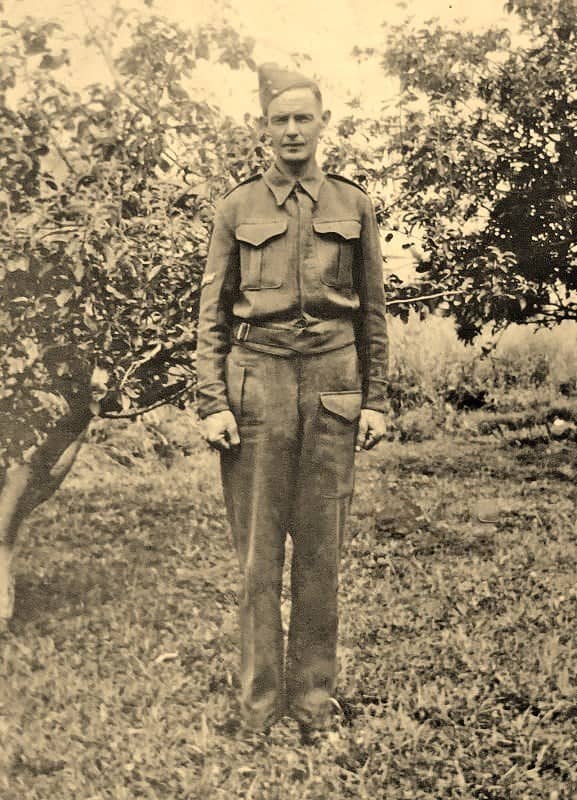

38407 Sapper Clarence G. Egan, 21 Mechanical Equipment Company, NZ Engineers (NZE), 2NZEF was attested at Trentham two days later on 14 Nov 1940, and preparations for overseas service began.

These men would become part of a non-divisional unit, soldiers who were chosen for their skill over any ability or aptitude for being turned into a soldier. The officers and NCOs of such units were also chosen on this basis, and because they related well to men engaged in this type of work, having come from similar backgrounds. Well drilled and sharp looking, regimented soldiers they were not – and had little interest in becoming so. They loved their machines and operating them, being far more comfortable pulling leavers than grenade pins. The Army needed these men, more particularly Britain needed them as they were in dire need of experienced heavy machinery operators, as well as machines that did not seem to exist in any numbers in the UK.

As a consequence the UK made a request of the NZ government for heavy machinery and operators for road building and the preparation of camps and facilities for the anticipated influx of troops, and for the construction of defence works against the potential threat of invasion from across the channel. The situation in the Middle East was also deteriorating rapidly with the German and Italian forces establishing strong infantry and armoured footholds in North Africa with their eyes set firmly on Cairo. The need here was not only for tracks and roads, but for anti-tank defences and protective bunds, excavation of below ground protection, storage and personnel facilities.

suffice to say that all attempts to convert the MEC men into functioning infantry soldiers could only be described as an abject failure, but as drivers and operators of heavy machinery and equipment, they were second to none.

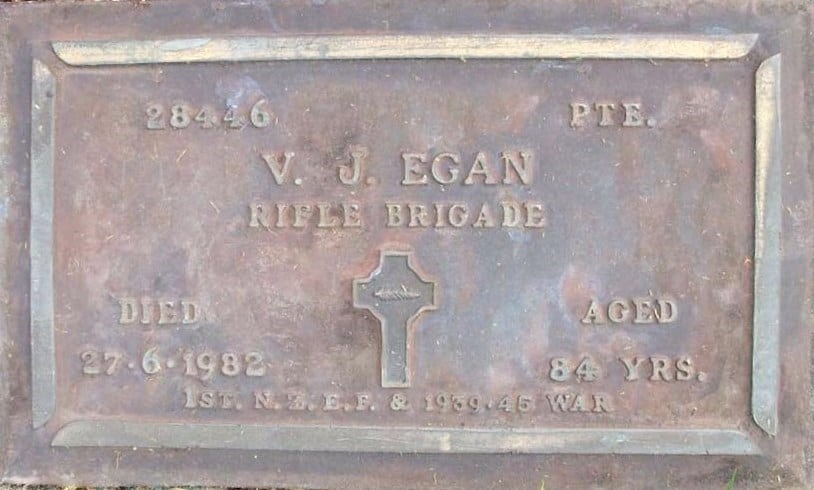

Note: ** 28446 Private Vincent Joseph Egan, a labourer and Clarence Egan’s elder brother, had served overseas in WW1. He embarked in October 1916 as a Rifleman with the 18th Reinforcements, 3rd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade. Pte. Egan sustained wounds to the left leg from which he recovered and discharged in April 1919 after 2 years 162 days overseas in England and France. He was awarded the British War Medal 1914-1920 and the Victory Medal for his service.

NZEF Base Camp Maadi

38407 Sapper Clarence G. Egan, 21 Mechanical Equipment Company, NZ Engineers (NZE), 2NZEF left New Zealand with the 4th Reinforcements on 1st February 1941 in the Nieuw Amsterdam, together with 8 Field Company, 18 Army Troops Company and a party of divisional and non-divisional Engineer reinforcements. On arrival at Bombay, because of the situation in the Red Sea – Eritrea and Somaliland were still in enemy hands — it was necessary to change into smaller ships which maintained a shuttle service to Suez. Those units not going on straight away went to a transit camp at Deolali outside Bombay. After six weeks in the transit camp, 21 Mechanical Equipment Company arrived at Port Tewfik on 23 March. The next day the unit marched into the 2 NZEF Base Camp at Maadi, about three miles from the Port.

The following is an account of one period in North Africa which gives an idea of the type of work and circumstances facing 21 MEC:

‘March and April were busy months in North Africa. The new arrivals were going through the usual routine of drawing stores including the assembly of some of the heavy equipment which had been partially dismantled for shipping purposes.

The situation in late March was that the frontier in Cyrenaica was held by bits and pieces of armoured formations, some mounted in Italian tanks which were scarcely mobile owing to the lack of replacements. Ninth Australian Division, less one brigade in Tobruk without transport, was supporting the armour. The enemy strength was known to be building up but no serious movement was expected for at least another month, when Imperial troops and transport would have replaced the formations and the 8000 vehicles that had been sent to Greece.

The enemy launched a counter-attack on 31 March by 5 German Light Armoured Division and two Italian divisions, one armoured and one motorised. The Allies were beaten back to Egypt by 11 April, with the exception of the Aussies and others in Tobruk.

Elements of 21 MEC loaded equipment on White 10-ton transporters destined for Bardia and the convoy proceeded towards Solum against a steadily increasing eastward bound stream of traffic. There was Air Force, Army and even Navy Detachments mixed together with apparent reckless abandon, and in great haste. On reaching Bardia at dusk the Section were suddenly re-directed to go to Tobruk with great urgency. The Lieutenant in charge of No. 1 Section takes up the story:

‘Having fed and refuelled and issued 5 rounds per man the convoy moved westwards at night without lights on the now empty road, arriving at the defences of Tobruk to meet a “Halt! Who goes there?” in the early hours of the morning and to be informed that we were either bloody heroes or bloody fools as the road was now cut, which accounted for the rumbling sounds, crossing laterally to the route heard during the night run; on reflection the sentry was right. We were bloody fools.

‘Having reached Tobruk and in view of the Bardia Commander’s orders re extreme urgency, a report was made to Tobruk Fortress Headquarters at 0230 hours to be met with a most encouraging reception and admonition “Go jump in the sea and let a man sleep.”

‘So, having fulfilled orders the section selected a piece of real estate and settled down for the remainder of the night. The equipment was unloaded and assembled to a background of dive and high level bombing attacks on the Fortress and harbour and subsequently handed over to an Royal Australian Engineer Company for operation.’

‘The work of assembly took a fortnight whereupon they embarked with Indian troops on the SS Bankura, but air-raid warning signals changed from white to red before they had settled down. It was soon painfully clear that the Bankura was on the target list, for near misses gave her such a list that she had to be beached. The shipwrecked sappers re-embarked on the corvette Southern Cross, survived another attack and reached Alexandria on 25 April. The engineers with 5 Brigade were having similar experiences between Greece and Crete about the same time.

While No.1 Section was undergoing its baptism of fire, No. 4 Section had departed to Matruh with shovels, ‘dozers and carry-alls to work on tank traps in case the enemy might venture farther east than the Egyptian border. Another job was the provision of berthage to replace the destroyed Matruh jetty. A wall of sandbags was built, then, with shovel and dragline, the seaward side of the wall was dredged and the spoil used to provide storage space. Destroyers slipped in after dark, discharged at the improvised wharf and were gone before daybreak.

No. 3 Section endured a few weeks in the ‘bullring’ (on the drill square) but were rewarded for their sufferings. They went to help on the outer defences of Alexandria and levelled the far bank of the Nubariva canal to provide a field of fire for pillboxes being constructed on the near side. They were quartered in Gianaclis, a small Greek community situated in the middle of acres of grapes. The sappers first ate the fruit for breakfast, dinner and tea, and then proceeded to distil the juice thereof. The results varied from awful to hellish.

No. 2 Section did not work as a unit but reinforced the other sections from time to time as well as doing sundry small jobs of their own. Not typical, but true none the less, was the experience of a detachment who were ordered to report to an Royal Engineer command in Alexandria. Nobody knew why they had come or what to do with them so they lived in Mustapha Barracks for three happy, uncomplaining weeks, during which time they were reinforced by another party, who also indulged with enthusiasm in the sea bathing and other pleasures that Alexandria provides so abundantly.

When Nemesis caught up with them they were sent to operate a drag-line at Amiriva where a defensive ditch was being excavated. The sappers claimed that the drag-line had originally been offered to Noah during his flood troubles but that he rejected it on the grounds that it was out of date. They had dug about half a mile of ditch with their prehistoric implement when new orders came that the ditch wasn’t wanted anymore and that they were to go on road repair work at El Alamaein. Nobody knew where the place was—then.’

Source: NZETC: History or World War 2, Chapter 4

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In February 1944, now a Lance Corporal (L/Cpl.) Clarrie Egan was given a furlough (leave) to return to NZ to see his family. Barely had he and Eileen had time to know each other again in the four short weeks at home, and Clarrie was off again back to Egypt. Trixie and Vince, both then in their twentys, ably supported their mother for at least another 18 months as the war finally came to a close, officially ending on 2nd September 1945.

Before the war ended L/Cpl. Egan had undergone a change of corps from NZ Engineers to the NZ Army Service Corps. With the corps change went his L/Cpl. stripe – his rank was Private. Suffice to say Pte. Egan survived the war physically, and returned to NZ in early 1946.

While he was in North Africa, Eileen, Trixie and Vince Egan (not to be confused with Vincent Joseph Egan, Clarrie’s older brother) stayed together at Church Street until Clarrie returned and life started to resume some semblance of normality again. Clarrie picked up where he left off with his work, returning to the timber industry as a mill hand. In 1937 Vince had married Valda TOWNSEND and the newly weds moved into a house in Tamaki. Clarrie, Eileen and Trixie also moved to Tamaki where Clarrie had a new job as a machinist (fitter & turner). Around 1960 Clarrie and Eileen (Trixie had married – Mrs Helena Alice MacPHERSON) moved house again, to 702 Tararu Road in Thames where Clarrie returned to work in the timber industry. By 1970 Clarrie (71) and Eileen were enjoying their retirement at Tararu Road when Eileen suddenly died in June 1971 at the age of 67. Clarrie stayed at Tararu Road however the loss of Eileen took its toll on him and he too died less than two years later on 25 March 1973, aged 74.

38407 Private Clarence Godfrey Egan, Army Service Corps, 2 NZEF was buried in the Serviceman’s Section of the Totara Cemetery in Thames. Eileen was also buried at the Totara Cemetery.

‘Lest We Forget’

Reuniting the medals

My search for the families of Clarrie and Eileen Egan started with their first born son – Vincent Edwin Egan. Vince was born in Taihape and married in 1937 to Valda TOWNSEND. The couple had four children – Wayne Vincent, Kevin Edwin Egan (born in 1953), Sheryl Anne BELL, and Shane Alfred Egan. Vince Egan pre-deceased Valda at Waiuku in 2004, age 79 – Valda died in Thames in 2016.

The logical place to start the search was Waiuku in case there was an Egan family member or connection who might have been able to direct my search. The telephone White Pages showed a number of Egans in Waiuku, I was in luck – I contacted Mr Pat Egan who confirmed that he had known Vincent Egan as they had coincidentally at one time, worked together for some years at Carter Holt Industries in Waiuku. Pat Egan as it turned out was NOT a relation of Clarrie Egan’s family at all. Pat’s presence in Waiuku was purely coincidental. I asked if he knew where I could find any of Vince and Valda’s family? No, but he had heard that one of the boys, Kevin Egan, may have gone to Australia several years ago after his mum had passed away.

As luck would have it Kevin Egan had a Facebook page so I sent a text message. I also found a family tree on the Ancestry.com website which had been authored by Kevin which meant I had a backup means of making contact. As it happened, when I did not get a reply to my text message, I sent another via Ancestry which must have got through – I received a text message from Kevin confirming I had the correct family. Kevin and his wife Lynne were residing in Queensland.

Clarence Godfrey Egan’s medals and Pay Book are now back in family hands, nephew Kevin being the very happy custodian. We suggested Kevin have the medals named, both for insurance and identity purposes should they ever go missing again.

Rather ironically Kevin had no knowledge that his uncle Clarrie was a Returned Serviceman! Like so many others, Clarrie Egan was one of those returned soldiers who never spoke of his experiences overseas. Having survived North Africa and El Alamein, which had claimed the lives of so many of his colleagues, not wanting to ‘revisit’ these memories was an entirely understandable reaction.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

All credit to Clayton Ross for making the return of these medals to the Egan family possible.

The reunited medal tally is now 294.