11/1663 ~ CAMPBELL LUPTON BOWEN

Out postings of medals that have been found or donated on the AWMM Cenotaph website and the Medals~FOUND page of our MRNZ website has resulted in yet another Canterbury mounted rifleman’s descendant family making a successful claim for his First World War medals.

Maree Bowen of Timaru contacted me after seeing a listing on our website for 11/1663 FARR.CPL R. BOWEN N.Z.E.F. and wanted to make a claim for what we were holding of his. She also raised the quizzical issue of the connection between two Bowen men who had the same regimental service number – Campbell Lupton Bowen and Richard Bowen? Maree told me that her late husband W.G. “Bill” Bowen, had been one of Richard Bowen’s grandsons. Bill had had a keen interest in his family’s military heritage and since his death a few years ago, Maree had continued with the research in order to pass it on to the younger members of the family. Maree confided that she also was on ‘borrowed time’ and so wanted to complete the Bowen genealogy project reasonably promptly. With time being of the essence, she was also aimed to gather together any associated memorabilia that could be passed on to the next generation of her family.

I had not yet looked at the Bowen medal case and so in discussing Richard Bowen’s background, was surprised to learn that Richard Bowen was actually Campbell Lupton Bowen who had been born in Victoria, Australia. My interest in the unusual was stirred and so I immediately put all else aside and launched into the Bowen case. The nicest part about researching this case was that (on the face of it) I already had a family descendant, however that fact still required me to prove exactly where Bill Bowen and family of Timaru fitted into Campbell Lupton (Richard) Bowen’s ancestral lineage so I could be sure the medal was going to the correct family.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The road to war

Of the NZEF volunteers, more than a quarter of the 8500 men of the Main Body, the largest group of soldiers to ever leave New Zealand’s shores, had been born in Britain or elsewhere in the Empire. Some 8,274 of these men were Australian born and either permanent NZ residents or were in the country ‘temporarily’ and chose to enlist with the NZEF. Campbell Lupton Bowen was one of these men.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Captain John Bowen, Master Mariner

John Bowen Esq. (1805-1862) was born at Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire, Wales, one of seven children of a well to-do family of landowners, David Bowen and Elizabeth DAVIES. Unlike the remainder of his siblings, second son John Bowen had no desire for a life on the land and had gone to sea at an early age, working his way up the ranks of the merchant service from Ordinary Seaman. By the time John Bowen had joined the Peninsula and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P. & O.) in 1842, he was a fully qualified Master Mariner, ticketed to command ocean-going passenger and cargo vessels in international waters. Captain Bowen remained a loyal servant of P. & O. for the next twenty years.

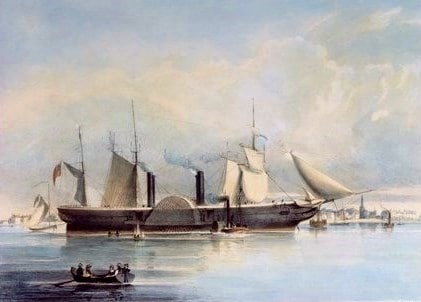

In 1846, Captain Bowen, then Master of the SS Hindostan, had just completed service in the East and was returning to England from Ceylon, as a passenger aboard the PSS Great Liverpool. Built in 1838 as a British trans-Atlantic passenger vessel, the PSS Great Liverpool was a large, three masted wooden paddle-steamer fitted with two side lever propulsion engines to drive the paddles. The ship weighed in at 1,540 tons and had a top speed of 12 knots.

The Great Liverpool had departed the port of Alexandria in Egypt, bound for Southampton, under the command of an experienced master, Captain Alexander MacLeod, also a Lieutenant in the RN. During the voyage Captain Bowen, as he was want to do, offered to assist Captain MacLeod by using his experience to take the daily reckonings (navigational position finding, sextant and compass readings etc).

At about o400 hours on the morning of February 24th, 1846, the Great Liverpool in the midst of a dark and stormy gale, struck a reef/rock eleven kilometres off Cape Finisterre on Spain’s west coast. The hull had been severely holed however Captain MacLeod managed to steam away until the engines shut down with the rising water. Liverpool then drifted towards land and eventually ran aground near Corcubine on the Guros Shoal about 300 meters from the beach near town of Guros. Lifeboats were launched into the tumultuous sea. All 150 passengers and crew aboard Liverpool were safely off-loaded and rowed to the shore. Three passengers however – a Mrs Archer, seven year old Miss Morris, and a native Indian servant/nurse – sadly were drowned when their lifeboat was swamped and capsized in the breakers as their lifeboat approached the shore.

Captain MacLeod was last off the vessel and over the ensuing days, watched as his ship was smashed to pieces on the shoal. Much of the cargo and passengers belongings not recovered, were strewn into the sea as the ship came apart only to be vigorously plundered by the local Spaniard population, despite MacLeod’s equally vigorous protestations to the Spanish authorities. They did nothing.

Captain MacLeod immediately wrote a detailed letter to his employers informing them of the ships fate and the subsequent circumstances he found himself with the unhelpful Spanish authorities. He is believed to have been mortified at the loss of the ship and his three passengers. In a state of utter despair, he committed suicide in the Spanish hotel he was staying.

During the disaster, Captain Bowen (41) had distinguished himself during the dramatic night time rescue of the passengers and crew, while assisting Captain MacLeod to manage the damaged ship and the obstructive Spanish authorities. Captain Bowen was called upon to give expert witness testimony at the subsequent judicial inquiry regarding the performance of the ship, crew and circumstances of the ship’s foundering. The inquiry completely exonerated Captain MacLeod acknowledging that under the extreme circumstances, he did everything possible for the passengers and crew while attempting to save the ship.

In appreciation of Captain Bowen’s heroic actions, the passengers held a Dinner in his honour in London during which he was presented with an engraved silver tea service. The inscription reads:

Presented To

Captain John Bowen

by the passengers on board

THE GREAT LIVERPOOL STEAMER

as a testimony of their gratitude

for his exertions

on the occasion of the wreck

OF THAT VESSEL

on 24th February 1846

OFF THE COAST OF SPAIN

~~~><~~~

Note: In 2016, the Spanish Ministry of Culture were assessing the viability of raising and restoring the ship which is believed to be buried under sand.

The Bowens of Pembroke

John Bowen was crewing coastal traders out of Liverpool at the time he was married in February 1834 at Walwyns Castle in Pembroke, Wales. His wife, Elizabeth (Eliza) REES (1811-1860) came from the hamlet of Steynton, quite close to John’s birthplace of Milford Haven and so there was every possibility John and Eliza had known each other while growing up. The Bowens made their home wherever John’s home port was which included Greenock in Scotland, Liverpool, Southampton and back to Liverpool. Once he had signed on with P. & O. in 1842, plying the trans-Atlantic and Far East routes meant he would often be away for months on end with the consequence that most of the five Bowen children were born while John was at sea. First born was Martha Elizabeth (1836, Liverpool) followed by John Fleming (1842, Liverpool), James (1844, Liverpool), Mary Catherine Jane (1848, Southampton) and last, William Campbell Bowen (1850, Southampton).

Captain Bowen served the P. & O. line loyally and was a capable and highly respected master mariner. He had not been without the odd sea-going drama himself during his career however it was unfortunate that one of his last memories should be of a similar incident. John Bowen and his wife Eliza had been married for almost 26 years when she died in 1860 at the age of fifty. John was heartbroken but had gone back to sea and soldier on. Not long after his wife’s death Captain Bowen’s own ship, the SS Euxine, ran aground (temporarily) in early 1862 – groundings were not infrequent, and an occupational hazard but this was a first for Captain Bowen. The result on an inquiry into the event was that two of his officers were reprimanded – Bowen was blameless. To John Bowen this was a stain on an otherwise faultless maritime career as a master.

On 20 June 1862, Captain John Bowen (57) died suddenly whilst a guest at the Spread Eagle Inn in Gracechurch Street, Bishopsgate, London. It may be argued that the loss of his wife and the grounding incident may all have played a part in John’s mental and indeed physical state at this time which may have required the intervention of a medical assistance. Captain Bowen’s death was ruled a suicide by the coroner, with the presence of opium** indicated. Many physicians of the day also advocated the use of opium to treat a range of disorders and ailments, the effects however were short lived with subsequent dosages needing to be stronger to avoid muscle convulsions and vomiting. Accidental overdosing on opium whist attempting to relieve symptoms was not unknown.

Note: ** The Anglo-Chinese Opium War (1839-42) was the result of China’s attempt to suppress the illegal opium trade, which led to widespread addiction in China and was causing serious social and economic disruption there. British traders were the primary source of the drug in China. Britain won the first opium war, gained commercial privileges and legal and territorial concessions and as a result, P. & O. entered the opium trade in 1847. Over the next 11 years the company shipped 642,000 chests to Great Britain.

The Bowen brothers

John Bowen’s eldest son John Fleming Bowen followed in his father’s footsteps and went to sea in 1860 at the age of eighteen. He also joined the P. & O. line, starting at the bottom of the ladder – an Ordinary Seaman. He travelled the world and at the age of 29, like his father, became a Master Mariner commanding his own vessels for P. & O. Captain John F. Bowen married a childhood friend, Sophia KYMER, and had a family of six children. His career was cut short when he died at the age of 45 in 1889, while in London.

By 1861, second son James Bowen had left home and went to seek work in London as a Commercial Clerk (probably with P. & O.?). News from Australia at this time filled the newspapers and there were a number of migrant packages on offer enticing men, women, families, tradesmen and professionals to the “lucky country” to build upon the prosperity that was being generated from the influx of prospectors and miners. Many had come from the gold rushes in California, to Australia when discoveries were made near the town of Orange in NSW in May 1851 (oddly enough at a place-name Kiwis will be familiar with – Ophir). The east coast cities of Sydney and Melbourne were flourishing as was Adelaide to the south. The apparently boundless opportunities on offer was all the inspiration James needed to migrate from London, a city which was overcrowded and beset with rampant poverty and crime, impacted by all the social ills that the industrial revolution had inflicted since 1740 (and would continue to do, until the First World War!).

With both his parents now gone, James Bowen (1844-1915) left London shortly after his father’s death and emigrated to Australia, disembarking in Melbourne. Initially quarantined at the Immigration Barracks until receiving the necessary clearances for health and customs, after adjusting to his surroundings and finding temporary lodgings in the city, James sought work as a Clerk (perhaps with P. & O.?).

James Bowen is listed in the 1871 Victoria Rate Records as being a Bookkeeper residing at 19 Park Street, South Melbourne in the Borough of Emerald Hill. The address in Park St consisted of around a dozen terrace houses rented out by the owner and occupier of one of the terraces – builder, Mr. James Stewart. That street address today is just one kilometre due south of the Flinders Street Railway Station in what is now St Kilda.

William Campbell Bowen, single, also emigrated to Australia. Little is known of William’s activities other than he had been working at a vineyard for three weeks before his untimely death was reported in 1876, ten months after his arrival in Victoria. The Coroner’s Inquest held on 6 May 1876 at Michael Derum’s “Carrick O’Shannessy Hotel”, determined that 26 year old William had been accidentally drowned on 15 April 1876 near Nagambie, Victoria, while attempting to cross the Goulburn River at night under the influence of liquor.

Echuca, Country Victoria

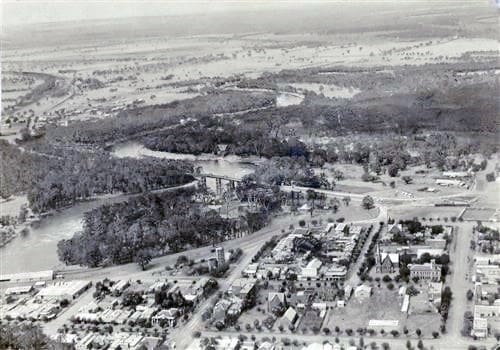

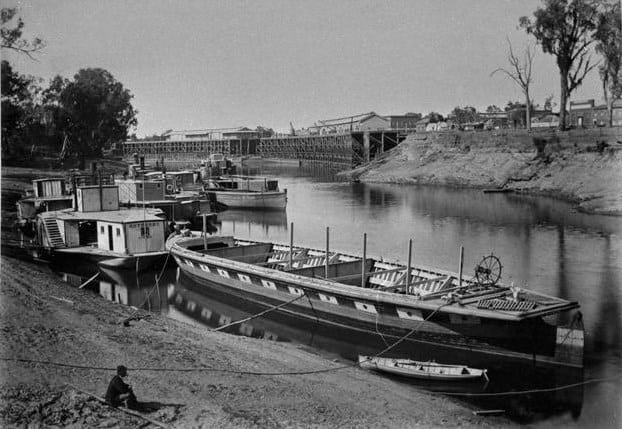

While living in Melbourne, James Bowen travelled to Tasmania and it was there he met eighteen year old Annie HILL (1854-1884) from Oatlands, one of the oldest towns in Tasmania that sits on the shores of Lake Dulverton, about 84 kms north of Hobart. Following a brief romance, James (24) and Annie were married at Oatlands in 1872 and then returned to Melbourne. James had ideas of becoming a farmer and so the couple moved north of Melbourne to the town of Echuca in central Victoria. James became a Land Agent which he hoped would ultimately facilitate his purchase of a farm. The following year, 1873, heralded the birth of their first child William James Bowen (1873-1937) at Craigieburn, now a satellite suburb of Melbourne on the northern side of Tullamarine Airport.

Echuca on the Murray River in the 1860s was barely a name on the map until a wharf, a hotel and church had been erected. Echuca eventually became Australia’s most substantial inland river port, but today is an important service centre for the surrounding agricultural region and a very popular tourist destination. The town is situated some 223 kms north-west of Melbourne, a typical country Australian town with its wide main street lined with retail stores, pubs and businesses of every sort with little activity in the heat of the day (it has more sunshine days per year than Queensland’s Gold Coast!).

Regrettably for James Bowen there would be no more children. Annie Hill Bowen died in 1884 leaving James alone with ten year old William James. Being in need of help to care for his son and their home so that he could continue to work, James looked to re-marry soon after Annie’s passing, which he did in September 1885. His second wife, Anne Hughes LUPTON (1859-1935), also known as “Annie”, was born in the South Melbourne settlement of Sandhurst, just beyond South Dandenong at the head of the Mornington Peninsula. Annie was the eldest daughter of John Edward LUPTON and Eleanor Norah HUGHES who married in Bourke, Melbourne in 1865. John Lupton was the Baliff of the Supreme Court. The Luptons died in Bendigo.

James and Annie Bowen’s first child of their own, born a year after their marriage on 6 October 1886, was named Campbell Lupton Bowen (1886-1940). Four years later, a brother, Bingley Arthur Lupton “Leigh” Bowen (1890-1951) was added to the family. For the next twenty five years or so the Bowen’s worked hard and established themselves as respected members of the community.

Land Agent & Farmer

Annie settled into the country at Euchuca while getting to know her young charge and step-son, William James. While William was taking school lessons, his father James worked at the Land Agency. Flooding from the Murray River had been a long standing problem in Echuca which the Bowens encountered not long after their arrival. Water levels were known to have topped six feet in the main street (and their Eyre Street house) as they discovered. As a consequence, James secured some land at North Echuca where his family would be free from the threat of further flooding and he could set about developing a farm, whilst retaining his business interests in town. As an extension of his Land Agency work, James Bowen was also appointed the Baliff for the Borough of Echuca (as was his father-in-law, Robert Lupton), an appointment he retained until he retired.

Western Australia had proven to be a huge draw card for those who chased the gold, the city burgeoning with wealth and prosperity ever since it was discovered in the Kimberly region in 1885. As soon as William James was of age, he left Echuca for Melbourne, later following the trail of the many thousands before him who had migrated westward after the most recent gold discovery had been made at Coolgardie in 1882, and Kalgoorlie in 1883. William married in 1901 to a Kyneton, Victoria girl, Amelia MILLEDGE (1875-1964). His occupation at that time, according to his marriage certificate, was a Law Clerk. William and Amelia had three children – William Milledge (1903-1982), Francis Milledge (1904-1995) and Kathleen “Molly” Milledge Bowen (1907-1996).

When William James Bowen (64) died at his bay side villa at 51 Victoria Avenue (still standing) in Claremont, Perth in July 1937, he was the Managing Law Clerk of a legal agency which also employed his son Francis, and daughter Kathleen, as clerks. William’s second son William Milledge Bowen became a motor mechanic.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It was the 12th of July, 1915 when 71 year old James Bowen died at his home, “Springbank” farm at Woodend in the Grampians region of Victoria. Annie his wife survived her husband by another twenty years, remaining at “Springbank” with her son Bingley Arthur L. Bowen. By 1919, Arthur (or “Leigh” as Bingley Bowen was usually known) and his mother had re-located into the South Melbourne suburb of Armadale, Balaclava. Arthur took a temporary job as a Driver until establishing himself as a Wood Merchant, a business he ran for the remainder of his working life. In 1922 Arthur married Juanita Louise CLARKE (1890-1985) and the couple had three children. First born in 1923 was a son named William who did not survive, followed by two girls, Juanita Vivienne “Una” (1927) and Annie Edith “Nancye” (1929) Bowen.

Mrs Annie Bowen died at Armadale in 1935, aged 75. Her son Bingley “Leigh” Arthur Lupton Bowen also died at Armadale, in 1951 aged 61.

A new life, new name

Whilst researching Campbell Lupton Bowen it was soon apparent he had undergone a name change, hence the initial confusion of there being two men with the same military service number. A common practice during earlier times was for men (or should I say boys) to alter their birth date in order to qualify by age to enlist for overseas military service – the minimum age was 20.

Those subsequently discovered to be underage (often the result of a letter from a distressed mother or girlfriend) were returned home as soon as was practicable, usually without penalty. Indeed some had even earned decorations for gallantry in the face of the enemy.

For those who enlisted under age and under a false name, provided they looked older than their actual age, these tended to escape detection. The need for volunteers was so great the process of proving ones identity or age was not particularly rigorous or airtight – it became a numbers game as the war went on.

Family folklore tells that at some point around 1900 Campbell Bowen, then about 14 or 15 years old, had a dispute with his family which led to an irreparable rift and his departure from Echuca. The upshot was Campbell apparently got on his horse and rode to Melbourne, never to return. When his horse was eventually found tied up near the Melbourne docks, a note attached to the saddle from him stated that he was leaving Melbourne (no destination was given). He had gone to New Zealand.

It was this move that almost certainly prompted Campbell Bowen to change his first name to “Richard” and drop his second name altogether, to minimise his chances of being found.

Hello, New Zealand

Whilst the date of Richard Bowen‘s actual arrival in New Zealand is hard to pin point, given the shipping schedules from Melbourne of NZ of the day, it would appear he arrived at either Bluff or Lyttelton between the years of 1902 and 1906, on one of the regular trans-Tasman cargo vessels that plied these routes. These ships could often carry a small compliment of passengers (10 or 12) for additional revenue, while others offered positions to those who were prepared to work their passage.

After his arrival, Dick picked up labouring work on farms around the South Island until he met Blenheim born Esther Francis ROBINSON (1888-1948). Esther was one of twelve children, eight sisters and four brothers all born in either Oamaru or Blenhiem, to northern Irish parents Thomas Alexander Robinson (1858-1940) of Ballymena, Co. Antrim, and Elizabeth McAFEE (1860-1939) of Londonderry, Co. Derry. The Robinsons married in Oamaru, later moving several times to Blenheim, Featherston and Christchurch. Tom Robinson worked as a Dairyman who collected cans of raw milk from local farms and took them to a central dairy where he was involved in separating the milk and cream, and making butter and cheese. After meeting Dick Bowen, Tom taught his future son-in-law the rudiments of dairying and so Dick too became a Dairyman.

On 10 Dec 1910, Richard married Esther Robinson at the residence of her parents which at that time was in Wairarapa area of South Featherston. Dick and Esther’s first three children were all born before the war. Their first, Kathleen Esther (1911-1989) was born at South Featherston. After Kathleen’s birth, Dick moved his family to their new home in High Street, Hawera. Twelve months later the Bowens celebrated the arrival of twins on 16 February 1912, Patrick Joseph Bowen (1912-1969) and William Arthur Bowen (1912-1971) at Whareroa in South Taranaki. Any plans the Bowens may have had for more children had to be put on hold due to the intervention of World War 1.

The Great War years

When war was declared on Germany by Britain on 04 August 1914, NZ being a loyal Dominion of the Empire followed suit on 5 August . Dick Bowen was a staunch supporter of the Empire’s military intervention in Europe and backed the call for the New Zealand government to commit troops following a request from the King. He also very likely considered that to serve overseas would be a once in a life-time opportunity to secure his family’s future, as well as be involved in a fantastic adventure abroad and one that he was not about to miss. Whether or not Dick’s initial rift with his family had involved any hindrance to a desire on his part to enlist for the Boer War, can only be speculated upon but, what was clear was the opportunity to enlist for WW1 service would probably be his last as he was not getting any younger.

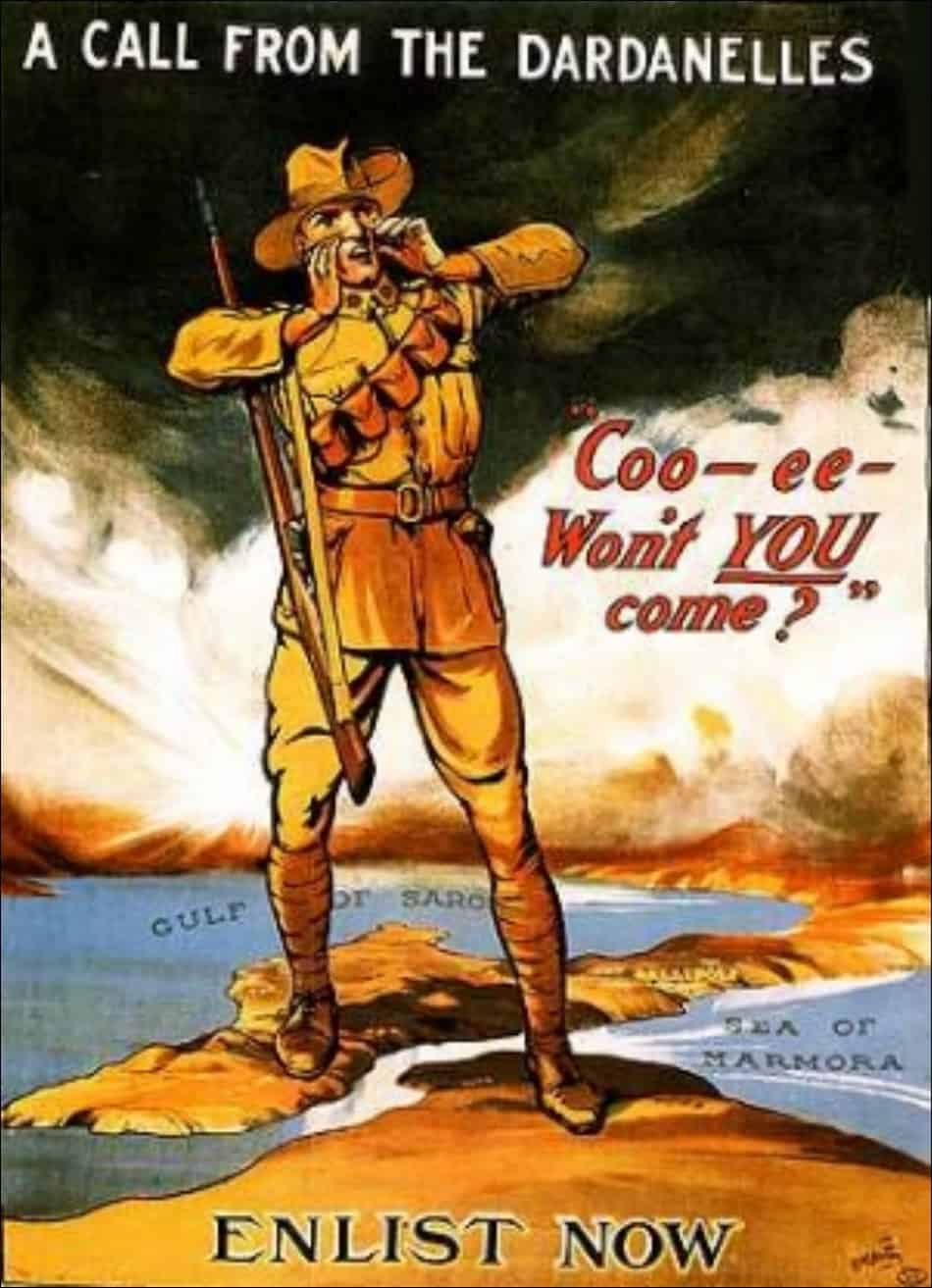

The war’s earliest days had seen a great surge of nationalistic fervour and patriotic enthusiasm to enlist. New Zealand was well-positioned to contribute to a British expeditionary force when war broke out in August 1914. Three years earlier it had created a Territorial Force which could provide the nucleus of an expeditionary force in the increasingly likely scenario of war breaking out in Europe. The declaration of war had brought forth 14,000 volunteers, many being territorial (part-time) soldiers, who swamped the Defence Department offices across the country to secure a place in the NZEF. The priority was for medically and physically fit, single men between the ages of 20-35.

In December 1914 the convoy carrying the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) steamed north through Egypt’s Suez Canal into the Mediterranean bound for the port of Alexandria. New Zealanders waited apprehensively for the first reports of the NZEF’s activities in Egypt, and then within months, news from the Gallipoli Peninsula following the ANZAC Division’s landings at Anzac Cove on 25 April, 1915.

The reality of the war soon struck home when the casualty lists started to appear in New Zealand’s daily newspapers. The initial patriotic fervour and surge of volunteers started to decline, as a result, the age limit was relaxed from Oct 1914-Oct 1915 in favour of men between the ages of 20 and 40.

Joining the WMR

As the NZEF’s progress in the Gallipoli campaign was reported in graphic detail, surprisingly any apprehension by those volunteers being readied to go as reinforcements was remarkably well suppressed. Indeed the majority who had volunteered just wanted to get overseas and ‘give it to Johnnie Turk’.

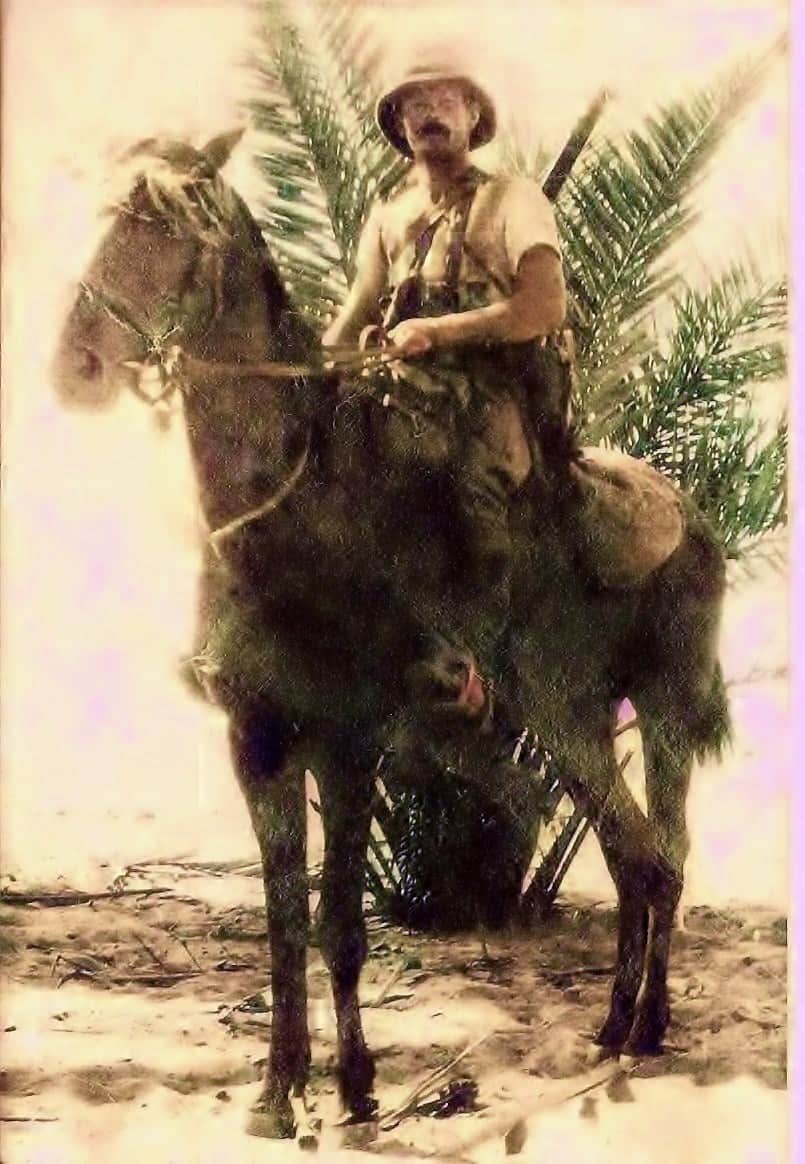

With a background of reserve service in the Australian Light Horse while living at Echuca, Dick Bowen had not hesitated to sign up at the Hawera Drill Hall in 1914. However, at 29 years of age, married with three children, Dick had not been the NZEF’s first choice to go overseas – he had to wait while he watched the Main Body leave New Zealand.

Dick Bowen’s call to go into camp coincided with the news of his father’s death at “Springbank” in July 1915. It is not known if Dick ever visited or even communicated with his parents or brother “Leigh” (Bingley) again, to reconcile the differences that had led to his sudden departure from Echuca?

His mind at this time was probably otherwise occupied when the call to report to Trentham in August came, where he would be Attested for military service and start his pre-deployment checks and training. Esther made arrangements for herself, daughter Kathleen (3) and the twins to stay with her parents Tom and Elizabeth Robinson and her youngest sister Monica Mary (1898-1980) who had moved from Oamaru to their home at 62 Gibbons Street in Sydenham, Christchurch.

Dick Bowen arrived at Trentham on 14 August 1915 and was Attested: swore his allegiance to serve for the duration of the war. He was allocated temporarily to ‘B’ Squadron, a holding squadron until training was completed. Once completed each trooper would be assigned to a specified vacancy in one of the mounted sections that made up the squadrons of the regiment. More often than not this was done after arrival in Egypt once final numbers of men on the ground were known, before mounted training started.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

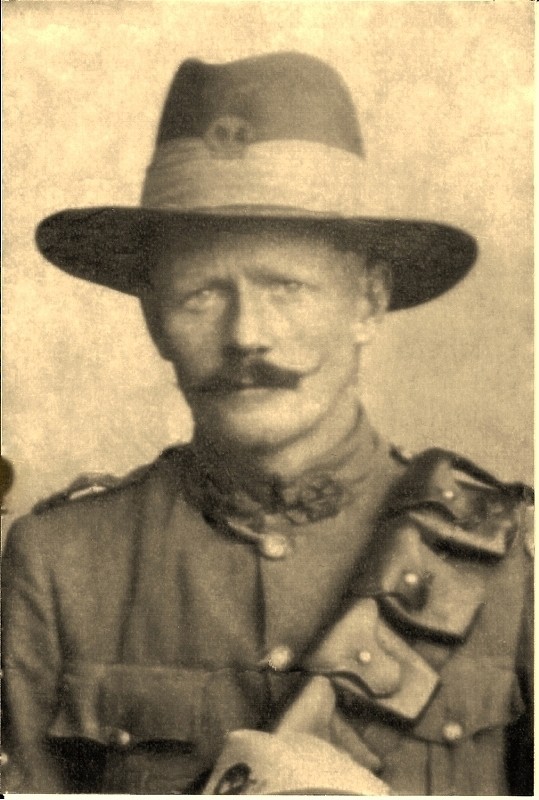

11/1663 Trooper Richard Bowen, known as “Bluey” to his mates, was 33 when he enlisted with the Queen Alexandra’s 2nd (Wellington West Coast) Mounted Rifles (more commonly written, 2/WMR). He would be travelling as part of the 7th Reinforcements which would be providing replacements to the NZ Mounted Rifles Brigade plus reinforcements for the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the NZ Rifle Brigade. Since the landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, battle casualties and sickness had taken a large toll more quickly than had been anticipated. Replacements were being sped into the Middle East to support the Imperial Desert Column to stem the advances of both the Ottomans and Germans in Sinai and Palestine.

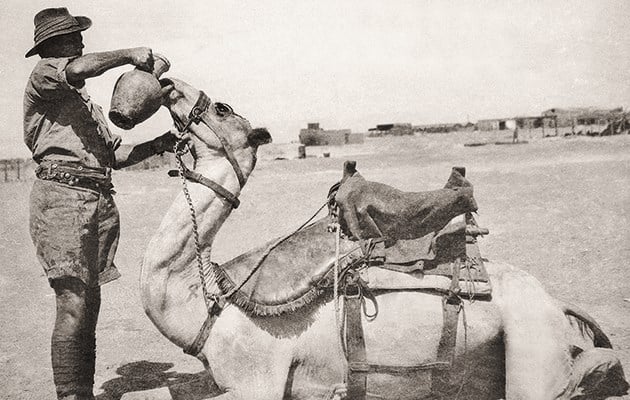

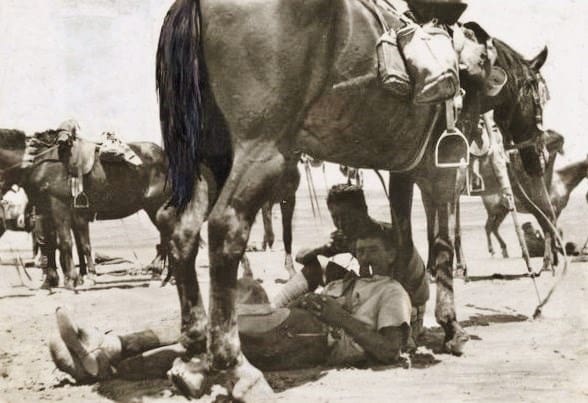

Tpr. Bowen had previously completed a standard three year part-time engagement in Australia with a Victorian Light Horse (VLH) regiment (possibly the 10th VLH Regt), a militia group of the 4th Light Horse Brigade made up from the Light Horse regiments of Victoria and Tasmania. With his background in horsemanship, Tpr. Bowen was temporarily promoted to Corporal Shoe-smith in October 1915 (one who smiths or repairs iron horseshoes). He would be responsible for fashioning and preparing horse shoes with the other regiment Shoe-smiths while on-board the ship, for fitting by the Farriers when they arrived in Egypt. He would later be temporarily appointed a Farrier-Corporal (one who actually fits the shoes on the horses). These temporary appointments were necessary to justify an increased rate of pay commensurate with skills, to exercise authority (as required) in the performance of their job, and/or to fill establishment gaps caused by the death, injury or sickness of any incumbents. Temporary rank was held only until the identified replacements were available.

NZMR Brigade in Egypt

The 7th Reinforcements left Wellington together with the 1 & 2nd Battalions of the NZ Rifle Brigade in three troop transport ships – HMNZT 32 Aparima, 33 Navua and 34 Warrimoo carrying a total of 2,437 troops on-board. Navua and Warrimoo left Wellington on 9 October 1915 in convoy with HMNZT 30 Maunganui and HMNZT 31 Tahiti. The Aparima did not leave Wellington until 30 November.

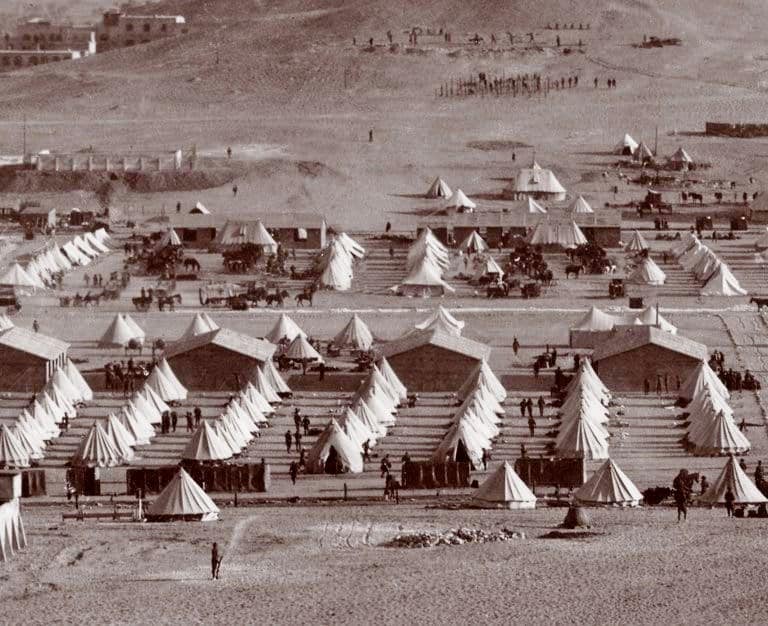

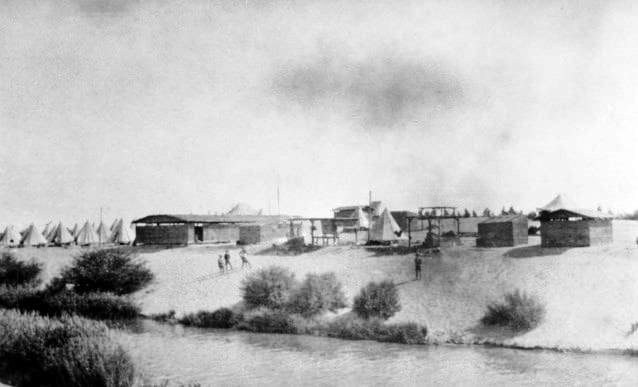

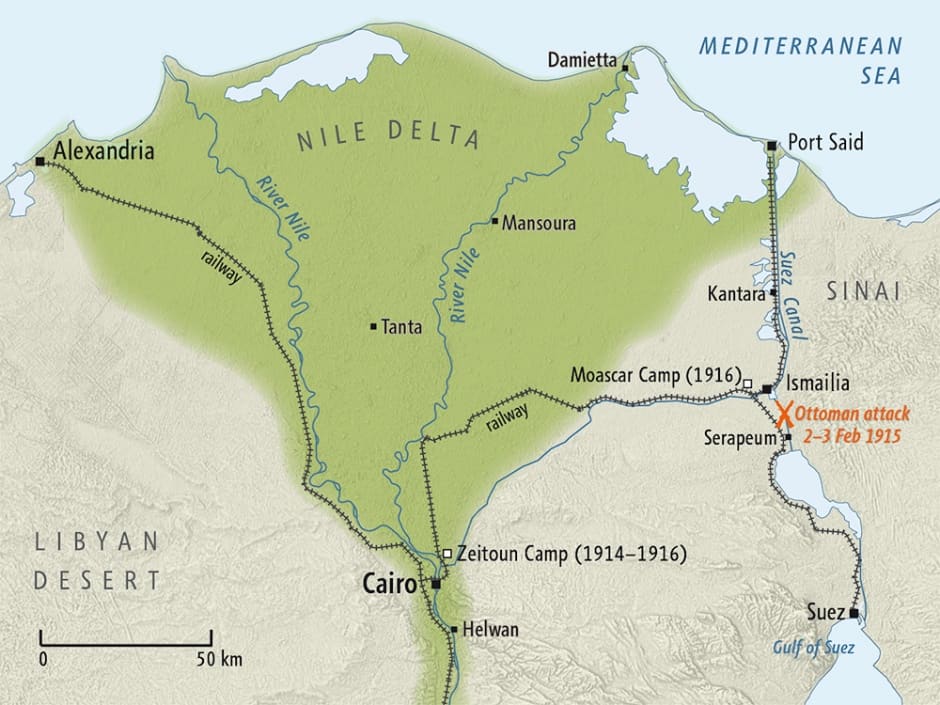

HMNZT 33 and 34 arrived together at the Egyptian port of Alexandria on 18 Nov 1915. Men and horses were disembarked, loaded onto trains and transported to Zeitoun on the outskirts of northern Cairo.

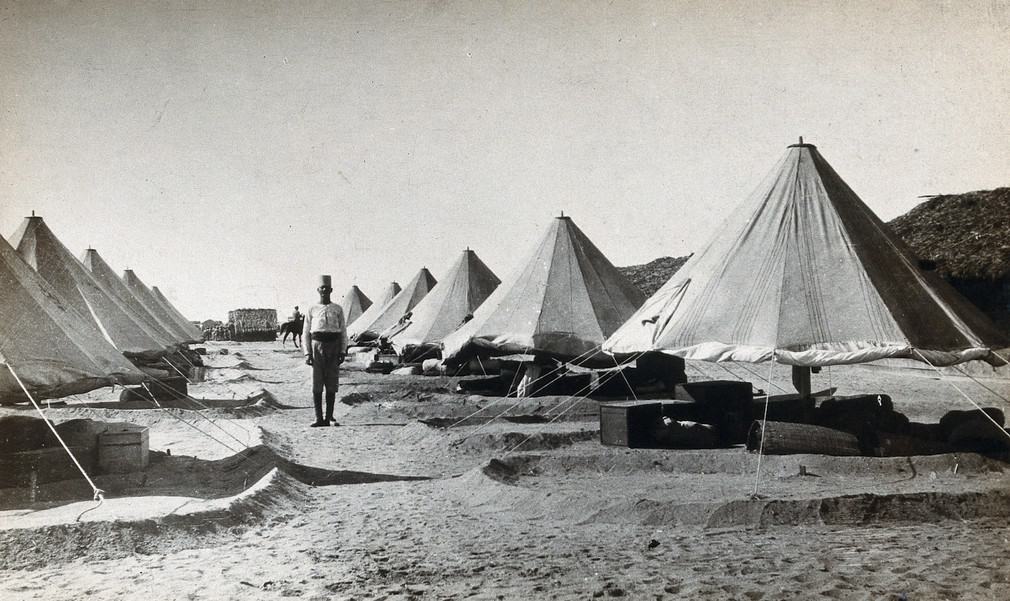

Here the NZEF’s mounted and rifle brigades Zeitoun Camp (about 9 kms NE of Cairo) was established. Both brigades would train in the surrounding desert for operations against the Ottoman Empire, conditions similar to which they expected to engage their enemy in. On his arrival at Zeitoun, Cpl. Bowen relinquished his temporary rank and reverted to Trooper. He was assigned to No.2 Squadron, NZMR Brigade.

WMR keen for action

For the first four months of 1915, the WMRs trained in Egypt. But their hopes of getting involved with action in defence of the Suez Canal and then in the invasion of the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli Peninsula were to be dashed.

The failure of the Ottoman Empire to succumb to the Anglo-French naval assault on the Dardanelles in February–March 1915 saw the New Zealanders join the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) which had been hastily cobbled together on the ill-conceived assumption that the Ottoman Army would fail to resolutely defend their homeland. The subsequent landing at Anzac Cove on April 25th by the combined divisions of Australia and New Zealand produced a casualty fest but little progress in ousting the well entrenched Ottoman forces who had dominated the high ground of the Peninsula. In May, the WMR and the rest of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (NZMR) were called upon (as dismounted infantry) in the desperate struggle to seize the commanding heights of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Over the next four months the WMR Regiment suffered more than half of all its casualties in the war.

First blood to the Infantry at the Canal

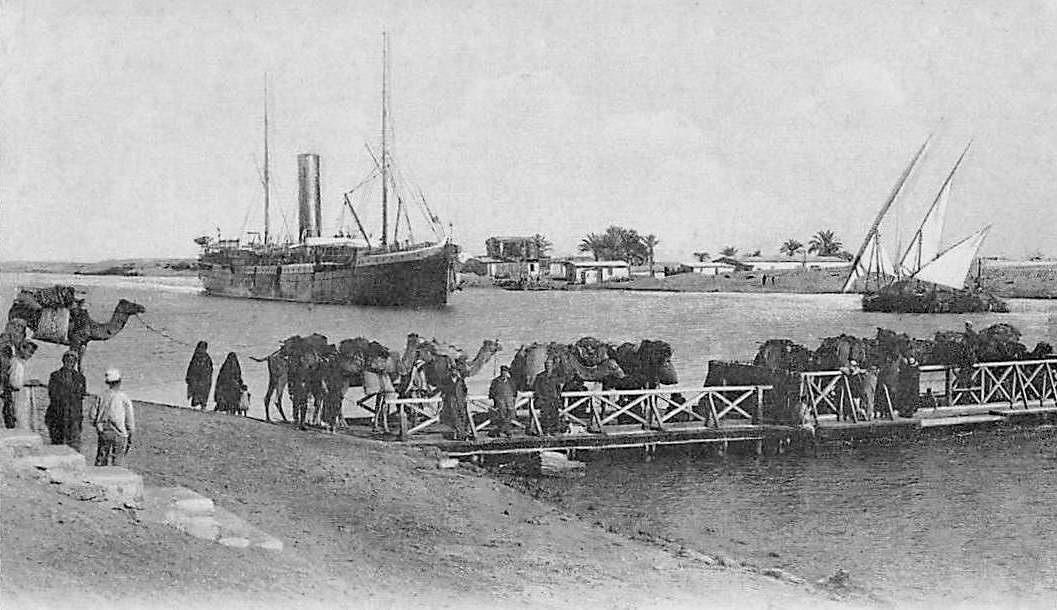

Meanwhile in the deserts of eastern Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula, the Ottomans and German forces were readying to make their bid for control of the Suez Canal and Sinai. At the end of January the troops were well advanced in their training. When word was received on the 25th that the Ottoman forces were advancing on the Suez Canal in three columns, the New Zealand Infantry Brigade was considered fit to support the 11th (Indian) Division, which was holding the defence of the Canal. The Auckland and Canterbury battalions were sent to Ismailia and the Wellington battalion to El Kubri near Suez. Moving at night, the Ottomans numbering around 16,000 were seen to be carrying boats to cross the canal with. The attack started at 3.20 in the morning of 3 February when the first attempt to cross in boats near the Indian Division was repelled. The enemy retreated and dug in on the eastern bank. Three attempts were made to cross the canal; all failed, one with the assistance of a Royal Navy warship in the canal firing salvos at the enemy’s artillery.

In the early afternoon orders were received for units to close on the Brigade HQ, and it was during this move that Private William Ham, 1st Canterbury Infantry Battalion of Ngatimoti near Motueka, was mortally wounded, thus becoming the NZEF’s first combat fatality of the First World War.

Post Gallipoli

The Gallipoli campaign concluded in Dec 1915 after a series of catastrophic attacks that produced no clear winner – the cause was effectively lost. What was clear to high command was that the casualty rate needed to be halted. The ANZACs started their withdrawal under cover of darkness on 15 Dec 1915. Consecutive night evacuations until 20 Dec resulted in the ANZAC forces being withdrawn without a single loss of life, the one clear victory of this disastrous campaign.

Once the WMR had arrived on Lemnos and been fed, watered, rested and had their medical and veterinary issues attended to, the WMR left Lemnos on 22 December aboard HMNZT Hororata and headed for Egypt. Four days later (Boxing Day, 1915) they disembarked at Alexandria and returned to Zeitoun Camp the following day. The WMR’s strength on arrival at Zeitoun was just 18 officers and 342 other ranks. This from starting strengths of 25 officers and 451 other ranks landed on Gallipoli. Since the landing the Regiment had sustained 640 casualties and absorbed 524 reinforcements.

Serapeum

After the conclusion of the Gallipoli campaign for the ANZACs, the majority of NZEF infantry rifle brigades, medical staff and other support elements in Cairo were moved to Mustapha near Alexandria in preparation for their move to France and the Western Front during the first few months of 1916. Only those infantry personnel selected to conduct training plus the 1800-strong New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, remained at Zeitoun Camp.

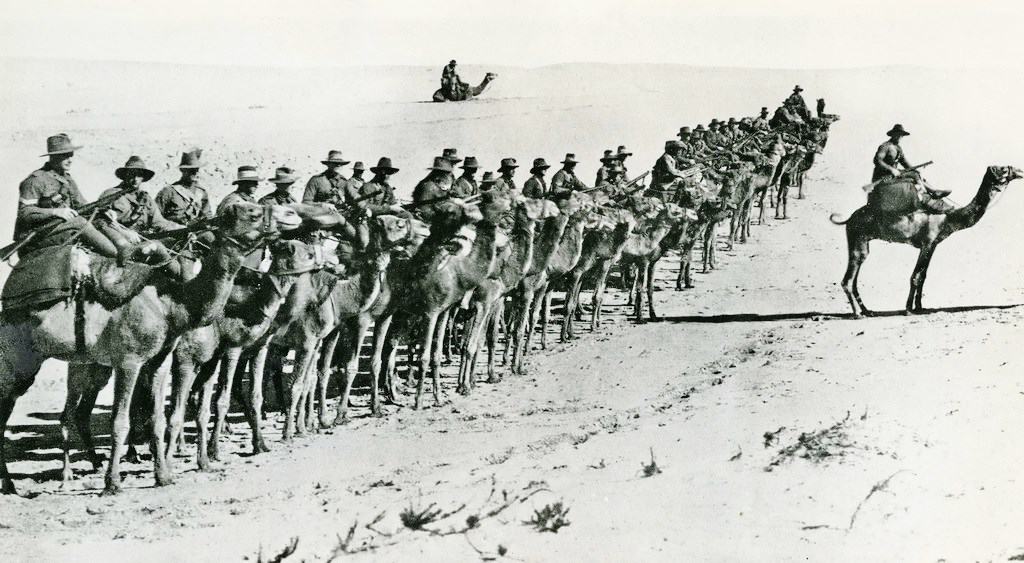

The NZMR Brigade were being transferred to Serapeum, an area south of Ismailia on the Suez Canal, to join with the British led Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) in defending the Canal. The EEF comprised a Corps of infantry and mounted forces (horses and camels), known as the “Desert Column” or DC (re-named the Desert Mounted Corps in 1917). The DC included two British Mounted Divisions, the NZ Mounted Division**, the Australian Mounted Division, and the Imperial Camel Brigade, with British Empire infantry formations to be attached when required.

Note: ** The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was made up of the following units:

- Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment (AMR)

- Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment (CMR)

- Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment (WMR)

- 1st New Zealand Machine-Gun Squadron (1 NZMGS)

- New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade Signal Troop (NZMR Bde Sig Tp)

- New Zealand Mounted Field Ambulance (NZMFA)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Imperial strategy

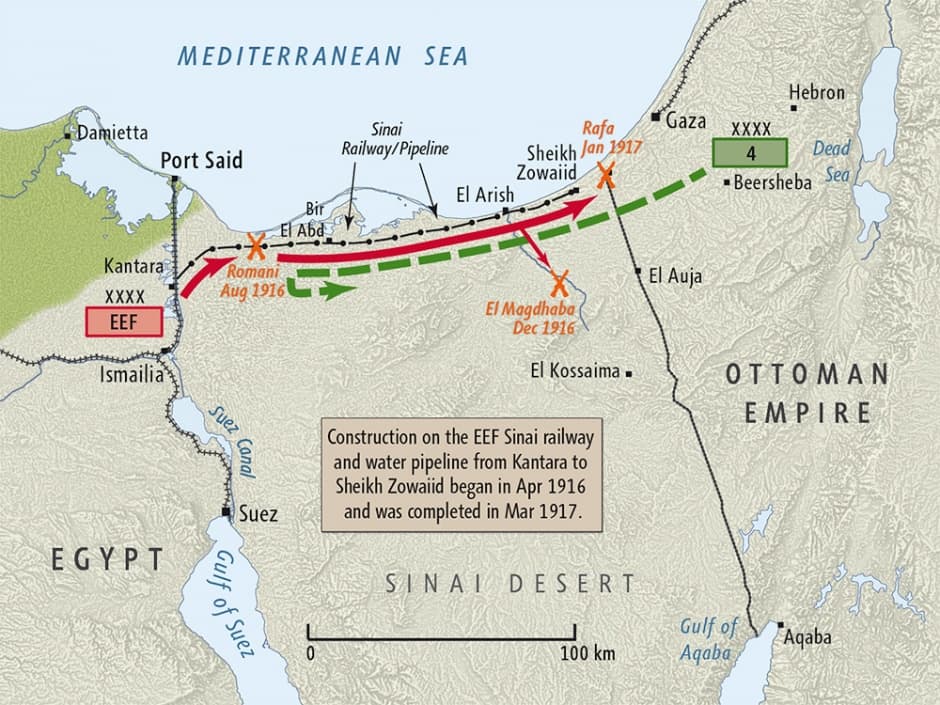

A rethink of British strategy in the region saw the emphasis on defensive operations changed into an offensive one designed to take the fight to the enemy and destroy or neutralise his bases in the Sinai Peninsula. This new strategy required rapid and reliable movement of logistics and supplies to support the advance of the mounted units in taking the fight to the Ottomans. This was made feasible by the construction of a railway and water pipeline eastwards from the Suez Canal across the Sinai Desert which would supply the food, ammunition and most importantly water needed to keep the British forces – the Egyptian Expeditionary Force – fighting in the harsh desert environment.

Australia & NZ Mounted Brigades unite

The EEF Commander revised strategy led to the combining of mounted units. The NZEF mounted brigade would unite with the Australian Light Horse brigades to form the ANZAC Mounted Division, its base depot being Camp Moascar to the west of Ismailia.

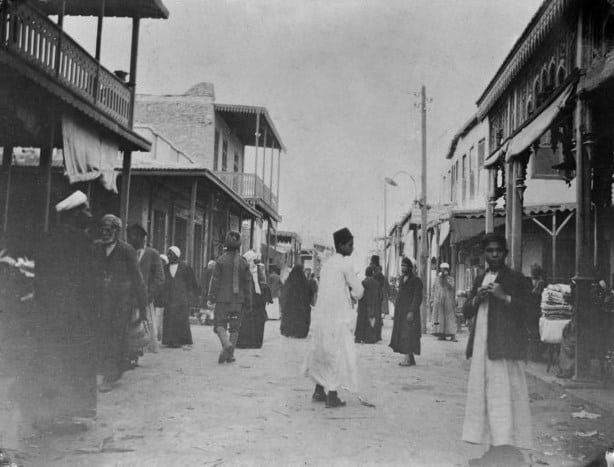

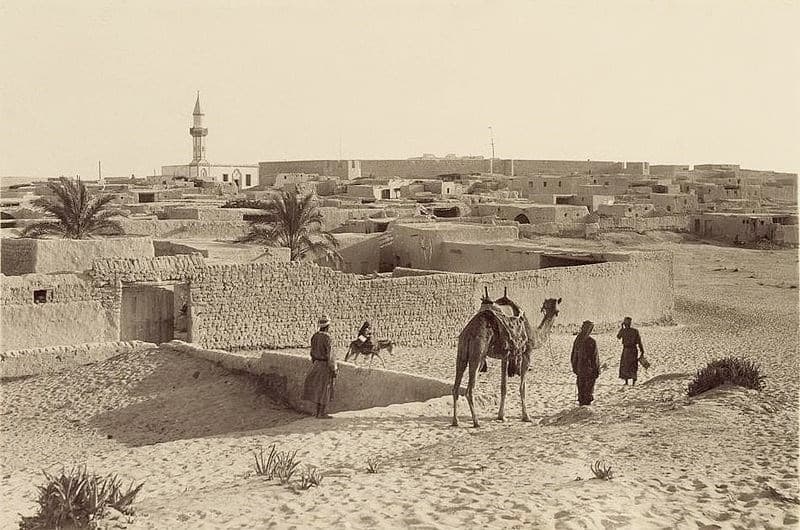

The town of Ismailia was built by French engineers and employees of the Suez Canal Company and is situated at the junction of the Port Said, Suez, and Cairo railway lines. The European part of the town is built in the French style, bright, spacious and well presented with public gardens and leafy boulevards, a welcome sight for desert weary mounted riflemen of the Anzac Division who had not experienced much semblance of civilisation since leaving home, more especially as life in the desert camp was at first very uncomfortable. Camp Moascar was situated in the desert about a mile to the west of Ismailia on the west bank of the Suez Canal. It was bounded on the southern side by the Sweet Water Canal (named for obvious reasons) which separated it from Lake Timseh, and on the eastern side by the Abbassia Canal. To the north was open desert, mainly hard sand, and to the west the ground was cultivated along the banks of the Canal which paralleled the railway to Cairo. All mounted troops arriving in Egypt had to pass through the camp for medical checks and training in mounted operations before being sent out with EEF patrols, or further afield to the Western Front.

Moascar was also an Isolation Camp. It was constructed to provide the final preparation of troops for entrainment to Alexandria and the Western front. As a result of numerous Australian soldiers whom had arrived in 1915 infected with measles, isolation camps were set at various locations to screen all soldiers arriving in Egypt as reinforcements for two weeks, checking for any illnesses such as measles, which can break out when people are crowded together for long periods. Any soldier who had contracted an illnesses after their arrival was sent to a hospitals at Kantara (on the eastern side of the Canal), to Alexandria or Cairo.

By the 8th of January, 1916 conditions were improving but there was still much overcrowding in the tents when the 7th Reinforcements arrived. The transport and horses, which had remained at Zeitoun, were now coming into the camp, plus the 2nd Battalion of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, recently employed on the western frontier in guarding the railway during the Senussi operations. The 4th Australian Brigade joined the NZ Mounted Division at Moascar shortly after. A good water supply had been piped in from the Ismailia water works by the N.Z. Engineers. Extra tents had been procured. The usual streets of canteens and bazaar shops had been erected by Maltese and Egyptian traders and a certain number of Institutes were in the course of construction by the Y.M.C.A. and the Salvation Army.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

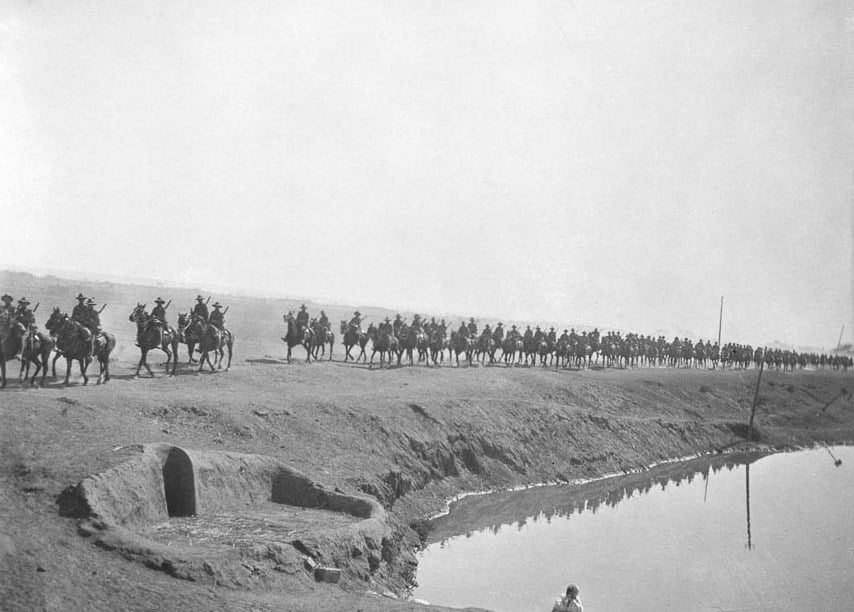

The Trek & Moascar

On 23 Jan 1916, Tpr. Bowen and No.2 Squadron left Zeitoun Camp on horseback with the remainder of the NZMR Brigade bound for Serapeum on the Suez Canal (via Moascar), 140 kilometres to the east. After bivouacking overnight the column pressed on, eventually arriving at Moascar seven days later on 29 January. The last leg of their journey from Moascar to Serapeum was a further 5½ hour trek south along the Suez Canal the next day.

On arrival at Moascar the WMR found there was a serious shortage of tents in the camp: most of the men were in bivouac which they found less comfortable than their old dugouts on the Peninsula; many indeed reverted to their cave-dwelling habits, attempted to burrow into the sand. The nights were cold and there was a shortage of blankets, and at times even of rations. Equipment and baggage was still stuck at Alexandria owing to congestion on the railways. The officers and men had with them only those few effects which they had carried on their person from Gallipoli or Zeitoun.

ANZAC Mounted Division

In the weeks following the WMR’s arrival at Serapeum, training , swimming and sports were the order of the dasy for the month of February. Tpr. Bowen was attached to the Training Regiment with the recent arrivals from the 5th Reinforcements. The new arrivals were familiarised with personal health and survival techniques, the conduct of desert operations, and briefed on the EEF force organisation (British, Australian, Indian, French and Arab locals) whom they would be operating with. Rehearsals for various scenarios were enacted to prepare the Troopers for desert operations. In addition, Tpr. Bowen was briefed on the specifics of his duties as a Squadron Saddler, a Shoe-smith and Farrier, and a mounted infantryman – all three roles he would be required to perform whilst serving with the EEF.

On March 11th the Australian and New Zealand (ANZAC) Mounted Division was officially formed as a unit of the Imperial led EFF, for the conduct of operations in the Sinai and Palestine (then considered part of the Ottoman Empire).

For Tpr. Bowen, his attention was momentarily diverted by a lesson that even an experienced Shoe-smith or Farrier was not immune from being reminded of from time to time – he suffered from a Lacerated Prepuce which necessitated him being hospitalised on 19 March for a number of weeks. For the uninitiated he had been kicked by a horse in the private parts which resulted in severe lacerations (an occupational hazard for a Shoe-smith or Farrier I should imagine – it hurts just thinking about it!).

The British Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, Lt. Gen. Archibald Murray, believed the canal could best be defended by going on the offensive and seizing control of the Sinai Peninsula from the Ottomans. He proposed building a railway and water pipeline (the black dotted line on the map) from the canal eastwards to a forward staging base at El Arish. The railway line was begun in April 1916, and designed to transport forces and logistical supplies required to support a campaign against the Ottomans.

Kantara

On 23 April 1916 the ANZAC Mounted Division received an urgent order to move to Kantara in response to an Ottoman raid on a British outpost near Katia. They covered the 40 km from Salhia to Kantara overnight, arriving in the morning to take over part of No. 3 Section of the Suez Canal defences.

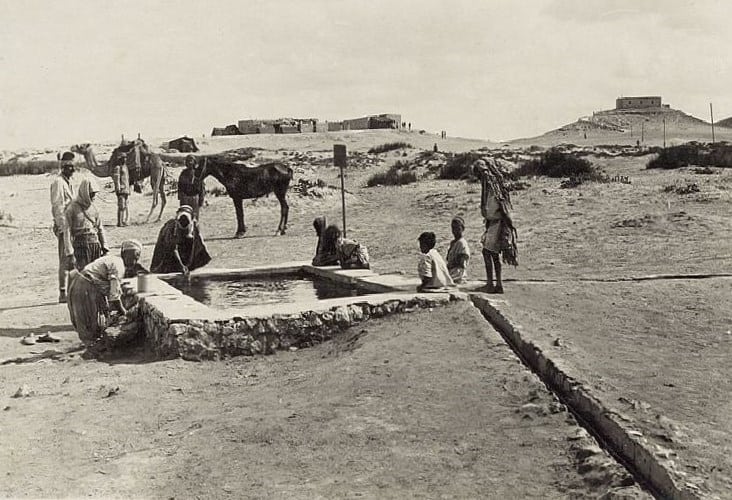

For the first half of May, the WMR and Auckland Mounted Rifles manned a series of defensive outposts near Hill 70, 10 km north-east of Kantara. The second half of the month saw the WMR and rest of the NZMR Bde. move to Bir et Maler, a village in the vicinity of the Romani and Quatia oases about 40 kms east of the Suez Canal. A reliable water supply and storage cisterns were located in the village and had to be protected to prevent it falling into Ottoman hands. The Bde. also conducted an active patrolling program of the surrounding desert, responded to Ottoman sightings and directions issued by the commander of the Desert Column. The Bde. also took time to rest and recover at Bir et Maler, replenishing their horses and carrying out essential maintenance.

By mid-May 1916, Tpr. Bowen’s wounds had healed and he was passed fit to re-join No.2 Squadron in the field at Bir et Maler. Tpr. Bowen was temporarily appointed to be a “Saddler” for a period of six weeks, and take his place in the WMR patrols.

May was also high summer in the desert and the heat at this time could be extreme. Particular care was needed to avoid sunstroke, heat exhaustion and heat stroke, and to ensure men and horses were well hydrated, another reason access to the water well was vital. One patrol from WMR No 2 Squadron suffered severe heatstroke casualties on a hotter than usual day, while the temperature inside the hospital tent at Bir et Maler was recorded at 52°C !

On 29 May, the Bde. left Bir et Maler and rode through the night to Debabis, 25 km south-east of Bir et Maler to make preparations for an attack on an Ottoman outpost at Salmana, 20 km north-east of Debabis.

Sinai – Battle of Romani, Aug. 1916

The only major battle of the Sinai campaign occurred during 3–5 August, the Battle of Romani.

In August 1916 near the oasis town of Romani, a 16,000-strong force from the Ottoman Fourth Army had attempted to destroy the advancing rail head. The attack failed attack (depicted by the broken green line on the map). British aerial reconnaissance and effective defensive preparations proved decisive in winning the battle, and from then on, the EEF advanced across the Sinai without further serious opposition.

Sinai infrastructure

On 17 November, the EEF rail head had reached 8 miles (13 km) east of Salmana, 54 miles (87 km) from Kantara. The water pipeline with its complex associated pumping stations built by Royal Engineers and the Egyptian Labour Corps had reached Romani, and Bir el Mazar, formerly the forward base of the Ottoman Army. The ANZAC Mounted Division took over Mazar on 25 November 1916 and by the 1st of December, the end of the most recently laid railway lines was east of Mazar, 103 km from Kantara.

Meanwhile the Ottomans had constructed their own branch railway line running south from Ramleh, on the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway, to Beersheba by re-laying rails taken from the Jaffa–Ramleh railway. It had almost reached the Wadi El Arish in December 1916 when the Battle of Magdhaba halted their progress permanently.

Battle of Magdhaba, Dec. 1916

On 21 December after a night march of 48 km, part of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) plus the ANZAC Mounted Division entered El Arish, only to find it had been abandoned by the Ottoman forces who had retreated to Magdhaba.

From El Arish, the ANZAC Mounted Division and the ICC launched a successful attack on the Ottoman garrison at El Magdhaba. By the end of the day, the casualty rate among the Ottomans forced their surrender. The town was taken along with 100 Ottoman prisoners. After this defeat, the Ottomans withdrew from all remaining outposts on the Sinai Peninsula, except Rafah on the Sinai-Palestine border. The cost of the battle to the Desert Column (DC) was 22 dead and 121 wounded.

The ANZAC Mounted Division returned to El Arish on 2 Feb 1917 where there was easy access to plentiful fresh water and supplies. In addition, they were also re-equipped. They exchanged their Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE) Mark III rifles for the new SMLE Mark III* rifles. During this period at El Arish, the Division had some much needed rest and recuperation after the demanding desert campaign of the preceding ten months. Sea bathing, football and boxing together with interest in the advance of the railway and pipeline were the main occupations of the troops from early January to the last weeks of February 1917.

On June 20th 1917 Trooper Bowen was one of 23 men the WMR received from the Training Regiment. He returned to No.2 Squadron and was once again appointed a temporary Saddler for a month.

Palestine Campaign – 1917-1918

The Palestine campaign began early in 1917 with operations resulting in the capture of Ottoman Empire territory stretching 370 miles (600 km) to the north, being fought continuously from the end of October to the end of December 1917.

Battle of Rafah, Jan. 1917

On the evening of 8 January 1917, mounted units of the Desert Column including the ANZAC Mounted Division, the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade, the 5th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade, No.7 Light Car Patrol and Artillery, rode out of El Arish to launch an attack on a 2,000 to 3,000-strong Ottoman Army garrison at El Magruntein, also known as Rafa or Rafah, located on the Egyptian-Palestine border near the Mediterranean coast. The attack at Rafah commenced on 9 January while four Royal Flying Corps RE8 aircraft bombed the German aerodrome at Beersheba simultaneously, grounding Ottoman and German aircraft not damaged or destroyed. This removed any chance of an immediate air counter attack on Rafah.

After a day of fierce fighting, Rafah was captured which meant the entire Sinai Peninsula was finally in EEF control. Victory at Rafah also meant the Suez Canal and Egypt had been secured from any possibility of a serious land attack. Thereafter allied infantry and the DC controlled the Sinai Peninsula with a series of manned fortifications and patrolling along the length of the railway.

Air war in the desert

One of the Turkish bombs fell directly on a group of camels assembled for inspection by the Battalion’s veterinary section. Twenty six camels were killed outright and another 15 had to be put down due to their injuries. In addition to the lost camels, two men were killed and another 19 wounded by the Ottoman air raid.

Progress on the supply line

As the British forces had pushed across the Sinai Peninsula, the infrastructure and supporting British garrisons were protected via a series of strongly fortified positions sited in depth along the road, railway and pipeline from Kantara on the Suez Canal to Rafah across the Palastinian frontier. By the end of February 1917, 388 miles of railway (at a rate of 1 kilometre a day), 203 miles of metalled road, 86 miles of wire and brushwood roads and 300 miles of water pipeline had been constructed. The pipeline required three huge pumping plants working 24 hours a day at Kantara, near a reservoir of 6,000,000 gallons. For local use, the pumps forced the water through a 5 inch pipe to Dueidar, through a 6 inch pipe to Pelusium, Romani and Mahemdia and through a 12 inch pipe, the main supply was pushed across the desert from pumping station to pumping station. At Romani a concrete reservoir contained a further 6,000,000 gallons, at Bir el Abd 5,000,000 and at Mazar 500,000 and another of 500,000 at El Arish. With the rail head at Rafah, Gaza was by then just twenty miles away, five to six hours for infantry and mounted units at a walk, and two hours distant for horses/camels at a trot.

Meanwhile operations for the ANZAC Mounted Division had extended into the Jordan Valley and into the Transjordan. The battles that were fought between February and May 1918 were followed by the occupation of the Jordan Valley while stalemated trench warfare continued across the Judean Hills to the Mediterranean Sea.

An armistice with the Ottoman Empire finally came into effect on 31 October 1918 thus ending the war in Egypt and Palestine, territory formally part of the Ottoman Empire and 11 days before a universal Armistice was declared signalling the cessation of hostilities of the First World War.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Illness and RTNZ

In May 1918, Tpr. Bowen was admitted to 65 Casualty Clearing Station with Pyrexia, an abnormally high body temperature, usually accompanied by fever. He was on-forwarded to 47 British Static Hospital in Gaza for a week with Gastroenteritis (commonly called Stomach Flu) – inflammation of the stomach and intestines, typically resulting from bacterial toxins or a viral infection, causing vomiting and diarrhoea. He was transferred to 27 British Army General Hospital at Abbassia in Cairo. After three weeks he was returned to Kantara and 44 British Static Hospital. In recovery Tpr. Bowen was released to the NZ run Aotea Convalescent Hospital at Heliopolis, a suburb of Cairo. After three weeks at Aotea, Tpr. Bowen was discharged as fit for duty in July 1918. He returned to the Desert Mounted Corps Rest Camp where he underwent an assessment to determine his fitness to continue serving in Egypt – or not? The assessment was not positive. Tpr. Bowen was to be “discharged, no longer fit for war service” and returned to New Zealand (RTNZ), due to his having Arthritis in the right knee and both knee joints, protracted Gastroenteritis and recurrent Pyrexia.

For Trooper Bowen, his war in the desert had come to an end. On 29 August 1918 he was invalided back to NZ on the Australian troopship HMAT Wiltshire. After completing his return from active service administration and taken the leave due to him, Trooper** Richard Bowen was officially discharged from the NZEF on 04 December, 1918.

Awards: 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18, Victory Medal

Service Overseas: 2 years 364 days

Total NZEF Service: 3 years 104 days

Note: ** The British War Medal was impressed for FARR.CPL R. BOWEN since this was the rank he carried at the time he qualified for the medal, and also represents the highest he rank held during his service.

Home again …

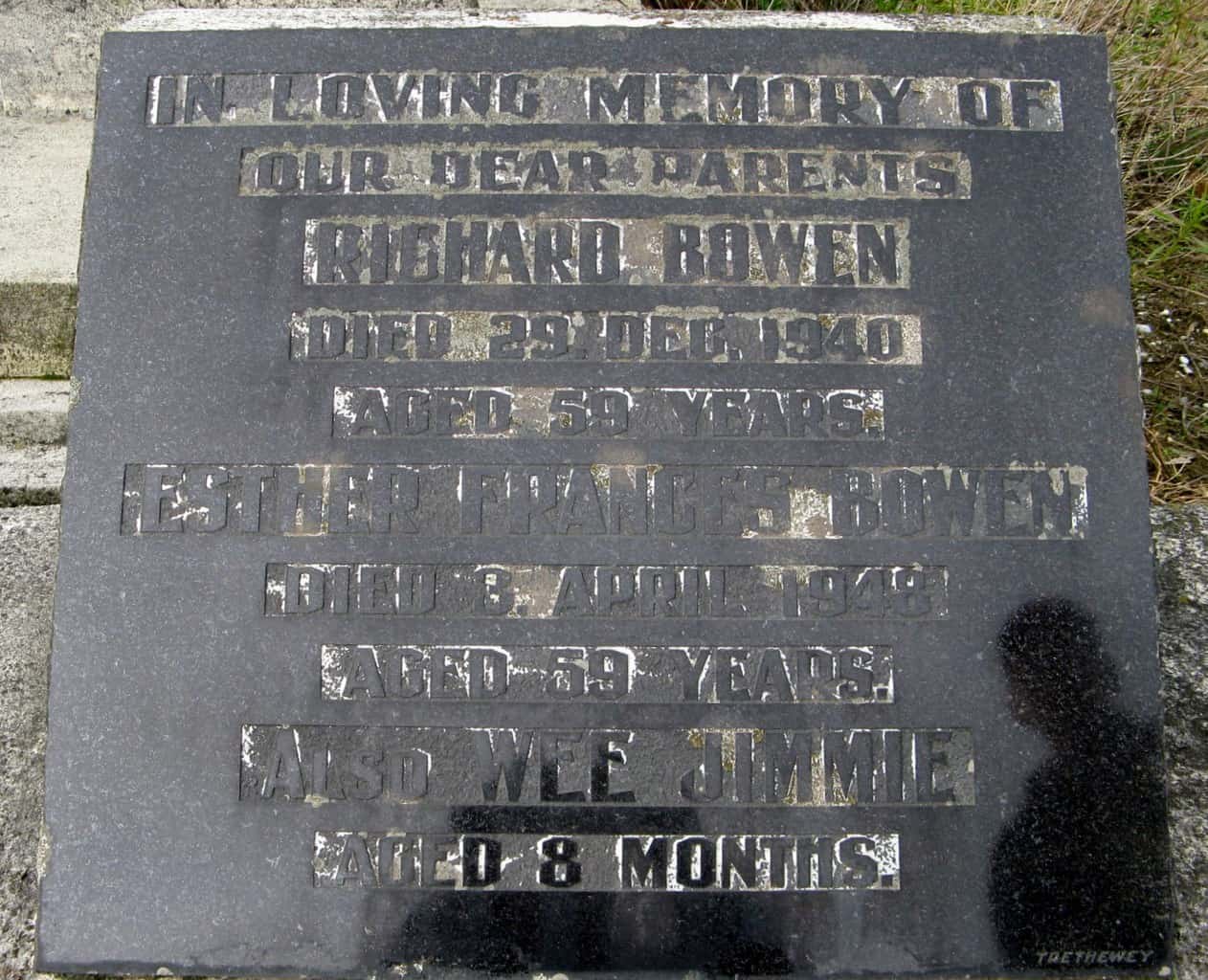

Dick Bowen returned to 62 Gibbon Street in Christchurch to find Esther and his family eternally grateful he had been spared the ultimate fate. The Bowens remained in Christchurch where Dick soon found employment as a Tram Driver with the Christchurch Tramways Board. He moved his family into 252 Lichfield Street where the family plan resumed resulting in four more children – Elizabeth Eileen (1920-1954), Eileen Anne (1921-2007), James Desmond (1925-1926) and Brian David Bowen (1927-1994). James (“wee Jimmie”) sadly died after just 8 months, on the 5th of August, 1926.

While working for the Tramways Board Dick had started to experience difficulties with his eyesight. Unfortunately the progress of his deteriorating sight did not abate and Dick was forced to retire from the Tramways. Many soldiers who had spent considerable time living and working in the desert experienced similar problems bought about from the effects of heat, sand abrasion and reflective glare which often led to infections, eye diseases and in some cases blindness. Dick was one of these – for the last few years of his life he suffered from headaches, a loss of vision and a weakness in his limbs. He was unable to get about without the assistance of a white cane.

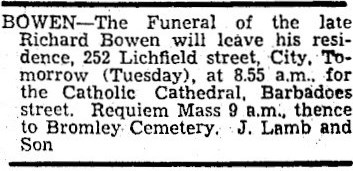

Christchurch Press ~ 30 December 1940

Richard “Dick” Bowen died in the Christchurch Public Hospital at just 54 years old (gravestone says 59) on 29 December 1940 after suffering a Cerebral Thrombosis (a blood clot in the brain stem that prevents blood draining from the brain). His funeral was held in Christchurch’s Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Barbados Street (destroyed by the 2010-11 earthquakes) and was attended by a large gathering of soldiers and Brothers of the H.A.C.B.S.

H.A.C.B.S.

The Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society (H.A.C.B.S.) was a church-based support network. It was founded in 1868 by a group of Irish immigrants, including Mark Young. In 1857 Young arrived in the colony of Victoria from Ireland. He moved to Ballarat, where he worked in a variety of occupations, including keeping a store with his brother. In 1861 he joined a gold rush to Otago, New Zealand, returning to Ballarat in 1862. Young ran the White Hart Hotel in Sturt Street and became very active in local affairs. He assisted other Irishmen in the foundation of the Ballarat Hibernian Benefit Society to provide sick pay and funeral benefits to its members, and to support St Patrick’s Day parades. Young later worked to achieve the amalgamation of that society with the Australian Catholic Benefit Society to form the Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society of which he was elected as its first president. By the turn of the century the society had expanded greatly, having branches all over Australia and NZ.

Each H.A.C.B.S. branch was named after a Catholic Saint and was run along similar lines to other Friendly Societies and Freemasons Lodges such as the Manchester Unity (Oddfellows), Forresters, Loyal Orange, Freemasons etc. Regular meetings are held and office holders appointed (President, Past President, Deputy President, Secretary etc). Officers holders wear a ceremonial collar (pictured) during conduct of Grand (national) and Branch meetings during the conduct of business, each collar being emblazoned with lettering indicative of the office held and the state/province the Branch belongs to.

The H.A.C.B.S. was established in New Zealand in 1869. Re-named in NZ the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society, it was a popular society among the numerous Irish prospectors and miners who arrived in NZ via the Victoria goldfields where many had already become members. Its popularity spread as did loyalty. Today the society still has a viable membership in excess of 2,500 members spread through all major cities in New Zealand.

Dick Bowen joined the St. Patrick’s Branch No. 82 of the H.A.C.B.S., one of twenty one Branches in NZ still in operation, which is located in Avonhead, Christchurch.

Brother Richard Bowen

It was the H.A.C.B.S. Brothers of St. Patrick’s Branch No. 82 who arranged Dick Bowen’s funeral.

Christchurch Press ~ 30 December 1940

Richard Bowen (born Campbell Lupton Bowen) was buried with “wee Jimmie” in the Bromley Cemetery, Christchurch. Esther Frances Bowen died eight years later aged 70 and was also interred with her family.

~ Lest We Forget ~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And then there were two …

The British War Medal, 1914-18 named to 11/1663 FARR.CPL. R. BOWEN N.Z.E.F. was acquired by me in 2012 from a deceased estate in Christchurch. As I was travelling south a few weeks later, it was my personal pleasure to call on Maree and personally give to her Cpl. Bowen’s medal. In addition I was able to give her some more good news. As I worked through Cpl. Bowen’s military file I found a small annotation written in red ink indicating that his Victory Medal had been unclaimed. In consultation with the very helpful Karley of Personnel Archives & Medals in Trentham, an investigation into the circumstances was undertaken. Karley was able to confirm that non-issue and subsequent permanent loss due to time and policy variations, had been the case. Given that so many years had elapsed and the whereabouts of the original medal was unknown, NZDF approval was given for an official replacement to be issued. We arranged for Maree to make an application.

Maree has since received Cpl. Bowen’s replacement Victory Medal, on behalf of her late husband Bill Bowen, grandson of Richard. That accounts for two of the three medals** originally presented to Cpl. Bowen. Maree remains ever hopeful that the third medal, the 1914-15 Star named to Farr-Cpl. R. Bowen, will turn up to complete his trio.

Note: ** The whereabouts of 11/1663 Farr.Cpl. Richard Bowen’s 1914-15 Star is unknown. If you can offer any information that would assist in its recovery (or buy-back) for Maree, you are requested to contact Ian at MRNZ.

The reunited medal tally is now 306.