NZ412861 ~ ARTHUR GODFREY BENNETT, RNZAF / RAF

An email I received from a Mr Tom Ireland in July 2020 really set in motion a chain of research that became one of the most significant cases I have had to date, due not to the medal recipient but rather because of the actions of his aircraft captain.tom Ireland was the incumbent Vice President of the Redcliffe Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Association in Queensland. A former British Army soldier who served with the Royal Signals from 1955 to 1972, Tom immigrated to Australia to take up an communications appointment with the RAAF from 1972 to 1978. Following his retirement from the military, Tom then took up a teaching position with the Queensland Education until he retired fully.

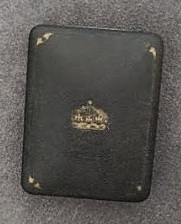

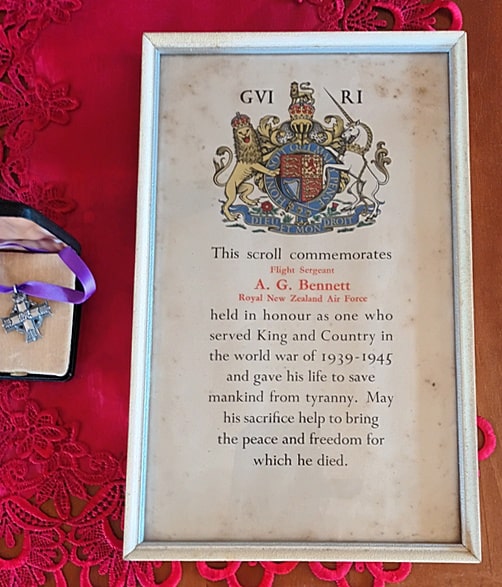

Being a keen military badge collector, Tom contacted had me in relation to a medal he was given him by a neighbour which had been named to a RNZAF airman, NZ412861 F/SJT A. G. BENNETT. Tom’s neighbour was an ex-RAN friend whose own neighbour on the other side, had in turn given him, apparently having bought it at a local market. Tom thought it may have been a gallantry award of some sort but it was in fact a New Zealand Memorial Cross (minus ribbon). Whatever the case, Tom was keen to see it returned to the airman’s family if at all possible, and so he sent it to me.

A cursory look through Cenotaph before the medal arrived gave me much cause for excitement. Flight Sergeant Arthur Godfrey Bennett had been a Wireless Operator & Air Gunner with 200 Squadron, a Coastal Command unit, flying Lockheed Hudson out of West African Base in 1943 when he died. But his was no ordinary death. Arthur happened to be one of five Kiwi crewmen on a B24 Liberator bomber that had attacked a German U-boat in August 1943, an attack which cost Arthur his life and all of those he was flying with when it crashed into the sea. However, his last flight was to become one of New Zealand air force legend, and one of the most highly regarded acts of gallantry in the air.

Bennett from Tipperary

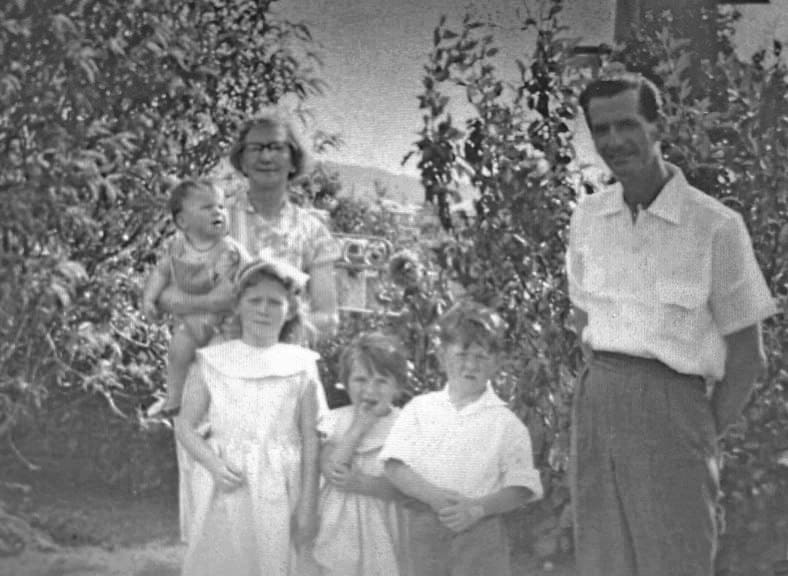

Arthur Bennett’s grandparents were John BENNETT from Templemore, Londonderry in County Tipperary, Ireland and Florence Emma MATEAR from Tullyallan in County Tyrone (now Louth). The first born of their five children was John Arthur Bennett (1874-1960) at Bourney, Co Tipperary. John immigrated to Australia in 1900 at the age of 26, initially working as a Gardener and later a Jockey before he met and married in 1913, Miriam May GALE (1891-1962) of Kinsale, County Cork. The couple settled in Preston, Bourke which is about 980 kilometers due north of Melbourne near the NSW-Queensland state border. John worked as a Dairyman while he and Miriam raised their family of six children.

The eldest child, Miriam’s son, was Albert Edward Burton GALE (1907-1987) who John adopted as a ‘Bennett.’ Following Arthur Godfrey Bennett’s (1913-1943) birth, the family then immigrated to New Zealand, arriving in Wellington in 1919. The Bennetts settled in the small rural village of Bideford, 26km north of Masterton, where John worked as a Contractor. Twins John and James Bennett born in 1918 regrettably died in infancy the same year. Miriam Bennett returned to Melbourne for the birth of her next child which turned out to a second set of twins, Thomas Alexander Bennett (1919-1982) and William Henry Bennett (1919-1983). The Bennett’s last child and only daughter, Mary Lavinia Maud Bennett (1923-2019) was also born in Melbourne.

About 1925 the Bennetts removed from Masterton to Whiteman’s Valley in Upper Hutt where John Bennett began work as a Gardener, an occupation he remained engaged in until his retirement. Arthur Bennett must have at some stage had his fascination with flying stimulated as he had joined the Wellington Aero Club in 1934. After securing a Farmhand’s job back in Masterton in 1936, Arthur also joined the Wairarapa & Ruahine Aero Club to continue with his flying interest which resulted in his gaining a solo pilot rating, an “A” License, on 12 Oct 1936 at the age of 22. Arthur returned to Whiteman’s Valley as a result of the Ford Motor Company opening an assembly plant at Seaview in 1936 where he got a job on the assembly line. The family then moved a short distance from Whiteman’s Valley to a home at Silverstream, an address listed simply as “Main Road, Silverstream.” It was from here Arthur Bennett left to join the RNZAF.

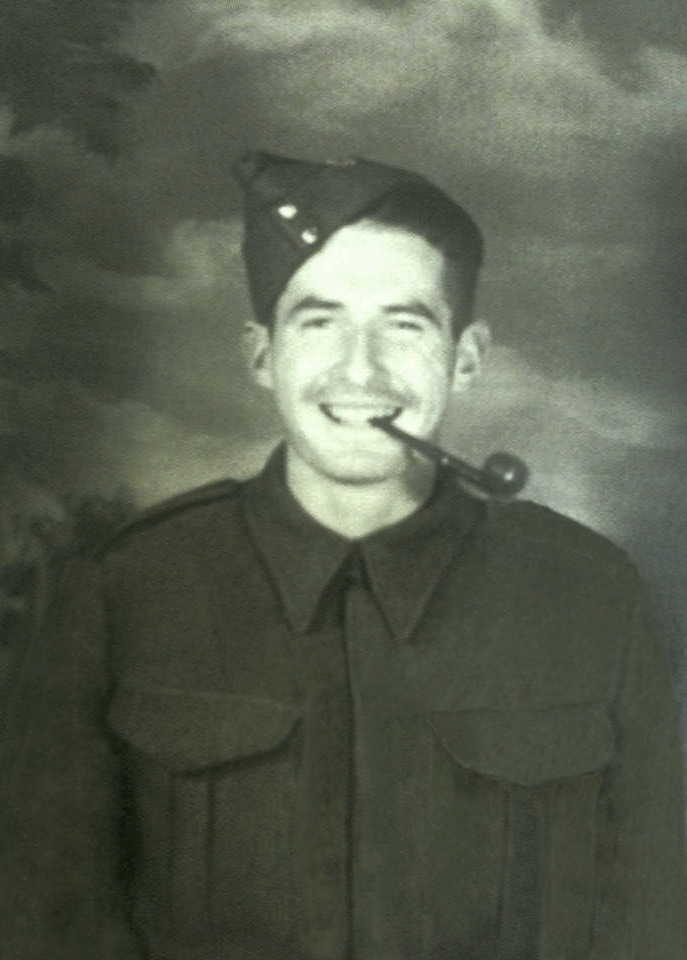

RNZAF enlistment

Given his love of flying, Arthur’s choice of the RNZAF was hardly surprising however it is unclear why his established skill in achieving a solo pilot’s rating at the aero club, did not transfer into his becoming a pilot trainee but rather, an Air Gunner u/t (under training). Aircrew Cadet Arthur Bennett commenced his basic training at the Initial Training Wing at RNZAF Station Levin in June 1941. Upon completion, the Cadets would be sent to Canada to undertake specialised aircrew training under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP).

BCATP – Manitoba

Note: ** TSS Awatea had been commandeered by the Royal Navy in 1940. She was used to transport Canadian troops to Hong Kong on 27 October 1941, arriving there on 16 November. On 11 November 1942 she was ordered to deliver No. 6 Commando Brigade to North Africa, but had some problems. Later on that day, she was sunk in Bougie by aircraft after putting up a heroic fight and delivered the last wave of specialized assault troops to the beach in Algeria.

Aircrew training

-

-

- 31 Aug 1941 – 24 weeks at No.3 Wireless School (3WS) at RCAF Station Winnipeg as a member of Course 1: Class 25c, and

- 12 Apr 1942 – 4 weeks at No.7 Bombing and Gunnery School (7BGS) at RCAF Station Paulson, also in Manitoba.

-

Having successfully passed both courses at RCAF Paulson, a graduation parade was held for the course on 11 May 1942 at which Cadet Bennett was presented with the half-wing brevet of a qualified Wireless Operator/Air Gunner (WOp/AG), the letters “WAG” embroidered on it. Qualification for the brevet also attracted promotion to the rank of Sergeant; officially he was now Sgt. [WAG] A. G. Bennett, attached RCAF/RAF. Sgt. Bennett was then posted to No.31 Operational Training Unit (31 OTU) in Nova Scotia for a period of ground training with effect from 5 June 1942.

No. 31 OTU was located at RCAF Station Debert in Halifax, Nova Scotia, a BCATP facility where pilots and NCO aircrew from all Commonwealth nations spent 12 weeks undergoing basic military ground training to equip them for service with the RAF. Following this training Sgt. Bennett was then transferred to No.1 “Y” Depot at Debert on 13 September, the Depot being responsible for managing all embarkations from Canada to the United Kingdom.

Sgt. [WAG] Bennett arrived in England on 26 Sep 1942 and reported to No.3 Personnel Reception Centre (3 PRC) at Bournemouth on 9 October, where all newly minted aircrew could relax after their months of training while waiting to be posted to a squadron. Bournemouth was (and still is) a seaside resort, the hotels normally used by peacetime holiday makers had been co-opted by the War Office for use as quarters for transient aircrew. Arthur was transferred to No.2 Personnel Dispatch Centre (2 PDC) at Morecombe on 27 Nov 1942, another seaside town in the City of Lancaster to prepare for deployment overseas. He had been assigned to 200 Squadron, a Coastal Command unit in which he would be primarily employed as a Wireless Operator on the Lockheed Hudson, a twin engine, light bomber that was being used for maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine operations.

200 Squadron, RAF

The squadron reformed at Bircham Newton, Norfolk on 25 May 1941 from a nucleus provided by 206 Squadron RAF. Equipped with the Lockheed Hudson for maritime patrol operations, 200 Squadron was deployed to Gambia in West Africa as part of the West African Forces, to undertake anti-submarine operations and reconnaissance patrols. The threat to Allied civil and military shipping from German U-Boats operating in the Atlantic and along the West African Coast shipping routes, was a constant threat to Allied shipping, and to the strategic Gibraltar Straits and Malta. The squadron left Britain for Gambia at the beginning of June 1941 to join a number of other squadrons that comprised the RAF’s 295 Wing, Coastal Command based at Jeswang in West Africa. The squadron had stopped at Gibraltar en-route to Africa to provide escort coverage for Hurricane aircraft being flown to Malta from the carriers Ark Royal and Victorious.

West Africa

The first five Hudson’s reached Jeswang on 18 Jun 1942 and began flying anti-submarine convoy protection missions over the South Atlantic with effect from June 30th.

Sgt. Bennett embarked for West Africa on 13 Dec 1942, arriving at Jeswang on 1 Jan 1943 to join 200 Squadron. He was one of a five man crew which comprised the Pilot in Command, No.2 Pilot/Observer (Navigator), a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, a Bomb Aimer/Air Gunner (in the nose bubble), and a dorsal turret Air Gunner, who remained together as far as was possible, in order to develop confidence and routines among themselves which worked so much better on operations than a crew who had not spent time together. Although the number of sorties being flown had reached 172 by September 1942, very little enemy activity had been encountered during that period. In March 1943, 200 Squadron was relocated from Jeswang to Yundum, a few kilometers south of the Gambian capital now known as Banjul.

In May 1943, Sgt. Bennett and his crew were detached from 200 Sqn and sent to No.111 Operational Training Unit (111 OTU) at Nassau in the Bahamas. The crew travelled by B24 Liberator and Commando aircraft via the African Gold Coast, Ascension Island, Brazil, Trinidad, Puerto Rico and USA where their Pilot in Command, New Zealander F/O Lloyd Allan Trigg, disembarked to attend a separate training course flying the Liberator’s maritime version, the PB4Y-1 Liberator. The crew continued on to Nassau arriving on 13 May. At 111 OTU the crew studied and practiced the intricacies of operations on the Consolidated B4 Liberator Mk V heavy bomber, the aircraft that would be replacing 200 Squadron’s Hudsons. With their training complete, the crew returned to Gambia crewing their own Liberator. They departed Nassau on 12 July and flew via Canada, Newfoundland, England and Morocco to arrive at Yundum on 18 July.

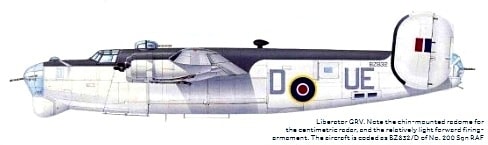

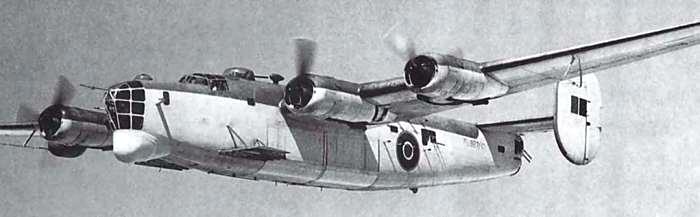

Consolidated B24 Liberator GRV

The Consolidated B24 was an aircraft manufactured in America for the British and French by Consolidated Vultee which the British named “Liberator”. By the end of July 1943, 200 Squadron had been fully re-equipped with new Liberator Vs which were an upgrade Mk IV version fitted with Mark III ASV [air-to-surface vessel] centimetric radar, the latest depth charges and included homing torpedoes, officially classed as Mark 24 mines [nicknamed ‘Wandering Annie’ or ‘Wandering Willie’]. The Liberator V also carried a number of rockets.

Nicknamed the “Flying Coffin”** the Liberator could be crewed with up to 10 men (200 Sqn would crew theirs with eight – Pilot, Navigator & co-Pilot, Bombardier/Air Gunner (formerly Bomb Aimer; also operated the nose guns), Flight Engineer, Wireless/Radar Operator and three Air Gunners to man the increased number of gun positions (waist, tail and upper gun positions). The Liberator also had twice the number of engines than the Hudson, and therefore a greater range and speed better suited to anti-submarine operations.

Note: The B24 possessed only one exit which was located near the tail of the aircraft which made it difficult to impossible for the crew to escape a crippled B-24, thus the nickname “Flying Coffin”.

Liberator GR Mk V ~ BZ 832/D

Sergeant [WAG] Bennett’s crew had been detached from Yundum to an airfield at Rufisque (Senegal) in French West Africa to conduct anti-submarine and convoy protection patrols. A veteran of 51 operations on the Hudson, Arthur had been promoted to Flight Sergeant by the time he and his fellow crew members assembled for a pre-flight briefing for their first Liberator patrol on 11 August 1943. They would be crewing Liberator BZ 832/D to be flown by their Kiwi skipper, Flying Officer [P] Lloyd Allan Trigg, DFC.

Trigg, a veteran of 46 Hudson sorties, briefed his seven-man crew which included five officers (two Kiwis including Trigg himself, two RAF Volunteer Reserve, and a RCAF officer plus three Flight Sergeants (all Kiwis). Collectively, this was a very experienced crew, the five New Zealanders alone having exceeded 250 sorties between them.

Liberator BZ 832/D’s crew members were:

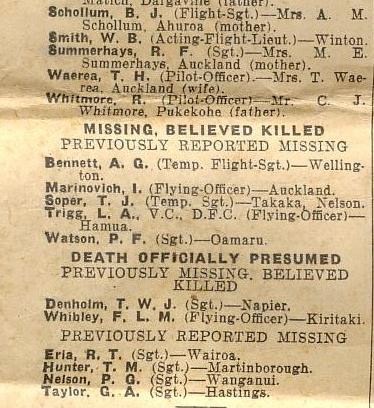

- PIC (Pilot in Comd): NZ413515 – F/O (P) Lloyd Allan TRIGG, DFC – RNZAF (Whangarei) Age 29. 47th op.

- 2nd Pilot: J/14450 – F/O [P] George Nicholas John GOODWIN – RCAF (Erickson, BC) Age 20.

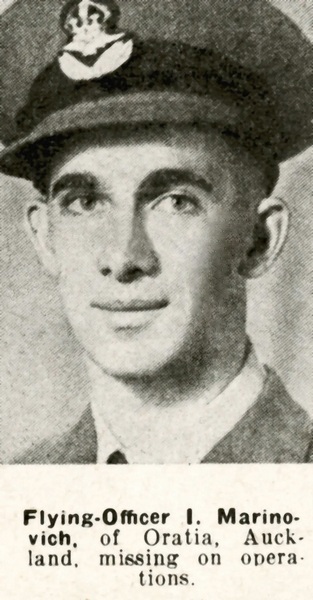

- Navigator: NZ413103 – F/O [OBS] Ivan MARINOVICH – RNZAF (Oratia, Auckland) Age 26. 50th op.

- Asst.Nav/(Nose) Gnr: 130137 – F/O [P] John Eric James TOWNSEND, BEM (Mil) – RAFVR (Belfast, IRE) Age 33.

- WOp/(Upper) Gnr: 158149 – F/O [WAG] Richard Albert BONNICK – RAFVR (Kingsbury, Middlesex) Age 27.

- WOp: NZ412861 – F/Sgt [WAG] Arthur Godfrey BENNETT – RNZAF (Silverstream, Upper Hutt) Age 29. 52nd op.

- Air (Waist) Gnr: NZ12908 – F/Sgt [WAG] Terence John SOPER – RNZAF (Takaka, Tasman) Age 21. 39th op.

- Air (Tail) Gnr: NZ414872 – F/Sgt [WAG] Laurence James FROST – RNZAF (Kowhai, Auckland) Age 22. 65th op.

Flying Officer R. A. Bonnick (RAFVR) of Kingsbury, Middlesex, missing on operations – no picture

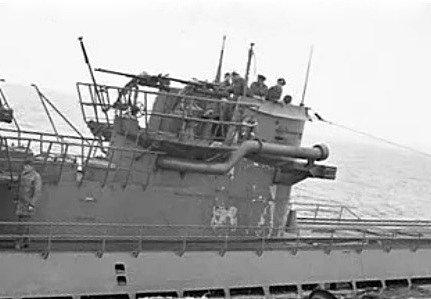

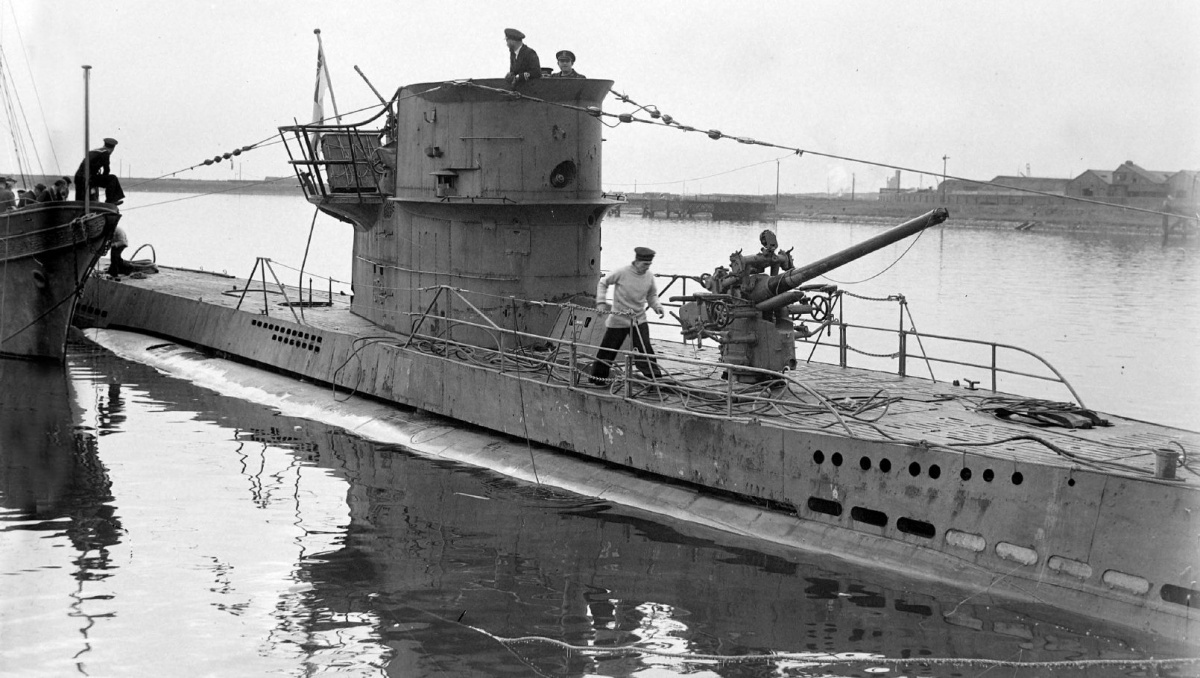

The Enemy – Unterseeboot 468 (U-468)

The Kreigsmarine’s U-468 of the 3rd U-boat Flotilla was a 500-ton Type VIIC German built submarine under the command of 26 year old Kapitän, Oberleutnant zur See** Klemens Schamong, his first command. The submarine was armed with 12 torpedoes, two single 20mm (.79 in.) Anti-Aircraft guns; one on the upper ‘bandstand’ and one on the lower ‘bandstand’. In addition, two x twin Mauser 7.92 mm (.311 in.) MG 81 machine guns were mounted on the conning tower bridge. Unusually, U-468 did not have the 88mm forward deck gun fitted which most U-boats of this class had at the time.

U-468 set out the main port of La Rochelle in the Bay of Biscay, SW coast of France with a compliment of 46 officers and men on its first ‘Wolfpack’ patrol ** on January 28, 1943. On 7 March, a convoy (ON-168) of British tankers was passing through bad weather off Cape Farewell, Greenland. At around 1820 hours, U-638 under the command of Kapitän, Leutnant Hinrich O. Bernbeck attacked a straggler of the convoy, the motor tanker (MT) Empire Light was the rearmost ship and the only one hit. The crew abandoned their ship but when it did not sink, they re-boarded. Five days later on March 12, U-468 was heading back to La Pallice from the northern Atlantic when she made contact with the MT Empire Light moving on its own course. Schamong attacked from periscope depth with three torpedoes. All missed. U-468 then surfaced and fired two more torpedoes, one of which hit. The tanker’s crew took to the boats, but after a short while, when their ship did not sink and the enemy did not appear, they prepared to re-board. U-468 then fired a sixth torpedo and the tanker sank. Partially crippled, the tanker did not sink and the attack was abandoned. Schamong finished the job with torpedoes and sank the Empire Light at 2210 hours. Forty five men had been lost in the attack while five (including the Master) survived and were rescued by the HMS Beverly.

While shadowing convoy ON-170 on 14 March, again south of Greenland, U-468 was attacked and held down for several hours by the corvette HMS Gentian, after which contact with the convoy was not regained. U-468 returned to La Pallice for repair and resupply for the next patrol to commence on 19 May.

Three days into the patrol at 0830 on 22 May, the U-boat was attacked by Grumman Avenger aircraft from the US Navy carrier-born Squadron VC-9, but suffered only minor damage. An hour later it was again attacked by Avengers from the same squadron, and this time, moderately damaged. Around 1600 on the same day, U-468 was making for La Pallice for repairs when it was attacked a third time by Avenger aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm’s 19 Squadron aboard the carrier USS Bogue, causing severe damage and forcing the U-boat to abandon its patrol and return to its base. With each attack, the submarine had defended itself with its two single Anti-Aircraft guns and the bridge mounted 7.92mm machine guns, but failed to damage any of the aircraft.

On 7 July 1943, U-468 again sailed from La Pallice under escort of minesweepers, on what would be her third and last ‘Wolfpack’ patrol. On this occasion U-468 deviated from her previous routine by following a course along the French and Spanish coasts instead of the safer route through the middle of the Bay of Biscay. These tactics enabled her to make the entire passage of the Bay without once being sighted or detected, a most unusual accomplishment in the opinion of the survivors. The U-boat was also in company of another Type VIIC submarine (believed to be U-373) until some point SE of the Canary Islands when they parted, U-468 proceeding to an operational area off the west coast of Africa.

The ‘Wolfpack’ patrol had lasted 36 days, had been uneventful and no attacks were delivered nor any sustained by U-468. On 11 August, U-468 was on her way back to La Pallice following an 8-hour patrol, proceeding submerged yet again along the west coast of Africa.

Notes:

Kreigsmarine – Nazi German Navy

Oberleutnant zur See – (Naval Lieutenant = the highest grade of Junior Lieutenant in the Nazi German Navy; equivalent to RNZN Sub-Lieutenant or NZ Army 2nd Lieutenant.

‘Wolfpack’ – A naval tactic where U-boats that usually patrolled separately, often strung out in lines across likely convoy routes to engage merchant ships and small vulnerable destroyers, were ordered to congregate once one had located a convoy and alerted the ‘Wolfpack’ which consisted of as many U-boats as could reach the scene for the attack. U-boat commanders could then attack as they saw fit. Often the U-boat commanders were given a probable number of U-boats that would arrive and then when they were in contact with the convoy, they made contact with each other to see how many had arrived. If their number were sufficiently high compared to the expected threat of the convoy’s escort ships, they would attack. This proved a success, leading to a series of successful pack attacks on Allied convoys in the latter half of 1940 (known as “the Happy Time” to U-boat crews).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sinking of U-468

Liberator BZ 832/D was airborne on its inaugural sortie at 0729 hours on Wednesday, 11 August from their base at Rufisque. After an uneventful three hours flying, F/O Trigg received information at 1105 hours to divert and hunt for a U-boat which had been bombed by a RNZAF PBY Catalina Flying Boat of 490 Squadron. At approximately 90 miles (144 kms) north of the U-boat’s last reported position, about 240 miles (386 kms) SW of Dakar, Trigg’s radar picked up a submarine on the surface at around 6,500 yards (6 kms). Trigg altered course and prepared to attack.

During the early stages of the U-boat war in the Atlantic the usual tactic to escape air attack was to dive as fast as possible. This became less effective as the war progressed, with RAF and Fleet Air Arm aircraft attacking with rockets, cannon and bombs while the submarine was diving. The ability of U-boats to stay on the surface at night while charging batteries for diving or using their higher top speed was also being hampered by Allied airborne radar and the development of a searchlight linked to it which could be switched on just before attacking (the Leigh light). U-boats began to increase their anti-aircraft armament and fight it out on the surface as their best chance for survival.

At around 0945 hours on the 11th, U-468 was surfaced while still proceeding north, roughly paralleling the West African coast. Trigg’s radar operator detected the surfaced submarine. Kapitän Schamong’s visual sighting of the Liberator most likely occurred at roughly the same time as Trigg detection, the two craft being about 5.5 kilometers apart. It was against the Kapitän’s policy to dive with the enemy so near, so Schamong elected to fight it out on the surface. Trigg altered the Liberator’s course and set up his attack profile as Schamong’s crew manned the two 20mm C/38, forty round magazine fed, anti-aircraft cannons, one located on the submarine’s upper ‘bandstand’ (an extension of the bridge on the conning tower), and one on a recently fitted lower ‘bandstand’ (a few feet above and in rear of the conning tower).

The Liberator crew braced for attack as Trigg descended to the 50 foot (15m) attack height, and sped towards the submarine. The anti-aircraft cannon fire from U-468 was accurate and chopped into the fuselage of this ‘no-deflection’ target, setting the aircraft on fire which quickly enveloped the twin tail. Trigg could have broken off the engagement and made a forced landing in the sea to douse the flames but to Schamong’s surprise, Trigg pressed home the attack, never deviating from his attack line to avoid the sustained incoming anti-aircraft fire. Every second the aircraft was in the air would increase the extent and intensity of the fire in the fuselage and diminish the pilot and crew’s chances of survival.

Approaching the submarine from the port quarter, Trigg opened the bomb-bay doors as the German gunners continued to pour fire into the underbelly of the aircraft. As the Liberator passed over the U-boat at just aft of the conning tower, Trigg released six depth charges which both hit and straddled the U-boat. The charges exploded, two of them within 2 meters of the hull which threw the whole U-boat violently upward, with fatal consequences. The U-boat Kapitän who had momentarily lost sight of the crippled Liberator, then saw the aircraft hit the water about 275m beyond the submarine and explode on impact.

US Navy Intel Report

The only account of the action was that given by the three surviving officers of the U-468, who described it in detail and were unreserved in their admiration of the courage and performance of the aircraft’s captain and crew. Kapitän Schamong’s interrogation aboard HMS Clarkia by US Navy Intelligence personnel is para-phrased in part here :

“Damage to the U-boat was catastrophic and she began to settle at once with water entering at several points. The engines and motors were torn from their beds, as well as the transformers and the bilge pumps. The fuel tank above the diesels, containing about 65 gallons of fuel, crashed down. The battery containers cracked. Nothing remained fixed on the bulkheads, and equipment and instruments were strewn all over the floor plates. The W/T room was a shambles and no distress signal could be made. The after torpedo tube fractured and a two-inch stream of water poured into the boat. Water was also entering the after battery compartment; and within a few minutes the U-boat was filled with clouds of chlorine gas.

Men immediately began to suffocate and could not get to their life belts. There was some panic aboard and only about 20 men succeeded in reaching the deck and jumping overboard. The U-boat sank on an even keel within 10 minutes.

Many of the men swimming in the water were suffering from the effects of the chlorine [gas poisoning] and were soon killed by sharks and barracuda. The Kapitän and the other two surviving officers kept the fish off by submerging their heads and “roaring.” After about 30 minutes, one rating discovered the Liberator’s rubber dinghy. He inflated it with the air bottle provided and climbed into it with two others. About an hour later the Kapitän, 1st Lieutenant and Engineer Officer who was supporting a rating on his back, succeeded in reaching the dinghy and also climbed into it.”

The prisoners’ subsequent account of their attacker’s coolness and courage greatly impressed British authorities. In re-accounting the Liberator pilot’s determination and display of fearless gallantry in spite of having a severely damaged aircraft, Schamong said:

“We opened deadly fire from our two 20mm cannons and the first salvo at a distance of 2000m set the plane on fire. Despite this, he (Trigg) continued his attack. He did not give up as we thought and hoped. His plane flew deeper and deeper. We could see our deadly fire piercing through his hull. Such a gallant fighter as Trigg would have been decorated in Germany with the highest medal or order.”

The US Navy Intelligence Report also gives an insight into the nature of Kapitän Klemens Schamong, the man:

“The Kapitän of U-468, Oberleutnant zur See Clemens Schamong, was a 26 year old Fähnrich zur See (Junior Midshipman) graduate of the Naval College at Mürwik, also trained as a Fähnrich zur See in a destroyer. His early career included serving in U-555 in a school flotilla, and as First Lieutenant in U-333 under Kapitän-Leutnant Cremer. U-468 was his (Schamong’s) first command. He holds the Iron Cross, 1st Class, and had also been decorated for service in the G.A.F. [German Air Force – Luftwaffe] to which he had been lent temporarily.”

“Schamong was a civilized type with considerable poise and charm, in marked contrast to many of the U-Boat officers recently encountered. He nevertheless had very firm ideas on the duties of a German officer in captivity, was constantly on his guard and divulged nothing concerning his boat except the story of her sinking.”

https://www.uboatarchive.net/U-468A/U-468INT.htm [SECRET C.B. 04051 (85) – “U-468” Interrogation of Survivors]

Aftermath …

The next day, August 12th, a rubber dinghy with seven survivors from U-468 was sighted by Air Sea Rescue Sunderland ‘H’ of 204 Squadron some 74 miles (120 kms) from the sinking point. The aircraft dropped supplies and signaled the corvette HMS Clarkia to pick up the survivors. HMS Clarkia reached the survivors at 0637 hours in the morning, their survival attributed to their good fortune of a rubber dinghy that had broken loose from the Liberator when it crashed which was retrieved by one of the submarine’s ratings.

In a touch of irony, U-468 was sunk on the penultimate day of the 1st Anniversary of its commissioning in the Kreigsmarine, 12 August 1942.

Despite several lengthy searches over the following days nothing of Liberator BZ 832/D or the eight crew members was ever recovered.

A second victory for 200 Squadron (along with No. 697 Sqn) followed six days later when U-403 was sunk.

Highest honour

As a result of Kapitän Schamong and his two officer’s interrogation testimony, Flying Officer Lloyd Trigg was recommended for the supreme award for gallantry in the face of the enemy – the Victoria Cross.

Born Allen Lloyd TRIGG at Houhora, Northland in 1914, Lloyd Trigg was educated at the Victoria Valley School and at Whangarei Boys High School before joined the RNZAF in June 1941 as a trainee pilot. On 16 January 1942, he became a Pilot Officer flying Lockheed Hudsons. He was posted to West Africa in December, and in January 1943, became part of 200 Squadron, Royal Air Force conducting convoy and aircraft escort flights, air reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols. In March 1943, Trigg was escorting a West African bound convoy when he spotted and attacked two U-boats. They were not destroyed, but they got the message and left the convoy alone. For these actions, Trigg was recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) which was subsequently approved in June 1943 however Trigg would never live to collect his award.

On 2 November 1943, King George VI authorised the posthumous award of the Victoria Cross to 413515 Flying Officer Lloyd Allan Trigg, RNZAF. His widow Nola Bernice Trigg (nee McGARVIE) received her husband’s Victoria Cross** and Distinguished Flying Cross from the then Governor General of New Zealand, Sir Cyril Newell RAF, on 28 May 1944.

Campaign medals awarded to Flying Officer Trigg and his crew include: 1939-1945 Star, Atlantic Star, Defence Medal, War Medal 1939-1945, New Zealand War Service Medal.

Note: ** This was the third and last ‘air’ VC to be earned by a New Zealander, although Sqn Ldr L H Trent’s (for his actions the previous May) was not promulgated until after the war. Trigg’s DFC was awarded in June for determined attacks against a U-boat on 28 March and another, two days later. This sortie and another on the same day were 200 Squadron’s first operations undertaken with the Liberator.

In Memorium

In addition to the campaign medals given to crew member’s Next of Kin, up to two Memorial Crosses could be awarded to the family of each man, intended primarily for mothers and/or widows. Where the mother had died, the first cross was awarded to the father, or if he had also died, to the eldest sister, or eldest brother where there is no living sister. A second cross could only awarded where the serviceman was married – to the widow, eldest daughter or eldest son. F/Sgt. Bennett’s mother Miriam Bennett received the Cross below.

Note: The NZ Memorial Cross replaced the World War 1 large bronze Memorial Plaque.

Apart from gallantry decorations and medals, the Cross was the only WW2 medal engraved with the deceased person’s name.

Liberator crew remembered

Arthur Bennett is remembered on the Lower Hut War Memorial, in the Hall of Memories at the Auckland War Memorial Museum and at the Airforce Musem, Wigram, Christchurch, the latter two also bearing the names of the other NZ crew members.

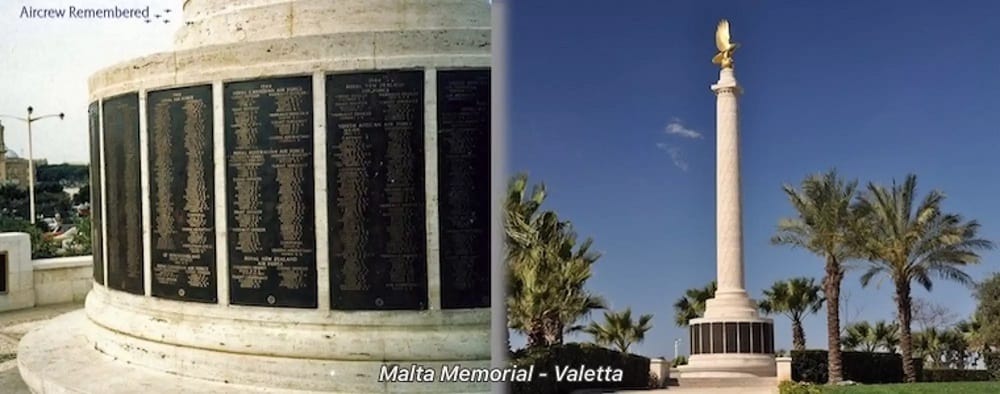

The entire crew of Liberator BZ 832/D are commemorated on the Malta Memorial at Floriana, Valletta on the island of Malta. The memorial is dedicated to the 2,298 Commonwealth aircrew who lost their lives around the Mediterranean, and have no known grave.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-submarine patrols continued until March 1944 but with little enemy activity, 200 Squadron was re-deployed to India on 16 March. The long range of the aircraft meant the squadron flew from Yundum to St. Thomas Mount on Ceylon (Sri Lanka), a trip that lasted thirteen days, arriving on 29 March. Convoy escort and anti-shipping patrols over the Indian Ocean began on 28 April 1944, along with some limited anti-submarine patrols, one of which, in December, saw the squadron damage a surfaced submarine. The squadron was re-equipped with Liberator VI’s in November. In January 1945, it also began to train with the Leigh Light, but then in April was transferred to Special Duties, flying supplies to agents and guerrilla bands in Burma. On 15 May 1945, 200 Squadron was disbanded and renumbered as No.8 Squadron.

The hunt for Arthur’s family

After an extensive search of the Hutt Valley and wider Wellington areas, no trace of a living member of the Bennett family was to be found. Certainly I discovered family several graves in Upper Hutt’s Akatarawa and Taita cemeteries containing family members but no real guidance as to where family members had ended up.

Strike 1

My initial search for any possible remnants of the original Bennett family in the Hutt Valley led me to believe I might have struck gold – I found a Bennett family who had arrived in the Hutt Valley at about the same time as Arthur’s family had arrived from Australia (the second occasion) and settled at Whiteman’s Valley, Upper Hutt. While scanning the web for confirmation I came across a 2011 newspaper article concerning a Mr Eric Ashley “Ash” Bennett. Ash had come to Upper Hutt at the age of three before going to Wairarapa were he was schooled and then worked throughout the South Island, including the Bluff Wool Store. He had returned to Upper Hutt with his mother in 1960, and since 1965 had been an Upper Hutt resident and fireman with the Upper Hutt Brigade. The article was written acknowledging his highly creditable 50+ years plus of service at the point of his retirement as the Station Fire Chief.

Reading the article, the instances in Ash Bennett and Arthur Bennett’s lives appeared interwoven and initially gave me to believe I had found a descendant. The similarities: Ash Bennett’s age and the time frame he spent in both the Wairarapa and Upper Hutt coincided closely to several of Arthur’s family members. Ash Bennett’s home at that point had been in Tawai Street near Trentham, while members of Arthur’s family had lived nearby in Whiteman’s Valley, Heretaunga and the neighbouring Silverstream. The clincher for me was that I had come across a reference to a Sergeant (Pilot) Thomas Samuel Eric Bennett (102 Sqn RAF) from Upper Hutt who had been killed on operations in World War 2. Possibly a relative? On the strength of this, and with the help of a former Army colleague Dave Ackroyd who had been involved with Trentham Fire Brigade for many years, made contact with Ash Bennett. Not remotely related was Ash’s response to my questions of association to Arthur Bennett’s family! F/Sgt. Thomas Bennett however had been his uncle. Both Arthur and Thomas Bennett are commemorated on the war memorials for Lower Hutt and Upper Hutt respectively. A miss was as good as a mile, so it was back to square one and the Bennett family tree – Strike 1, Out!

Strike 2

Arthur’s youngest brother was William Henry Bennett had married twice whilst living in the Hutt Valley, eventually leaving Upper Hutt and emigrating to New South Wales where he died in 1993. William Bennett had at one point lived for some time in Temora, a rural area I personally knew well, north of Newcastle. Being the youngest male of his generation I was hopeful of a Bennett connection in that area. The phone book showed two Bennett families living in Temora. The first phone number was disconnected, the second I left a message on the answer phone. Try as I might, I could not make contact with anyone at the still connected number – Strike 2, Out!

Strike 3

The next attempt was Ancestry family trees. I located one authored by Meirel Griffiths in England, a descendant from one of Arthur’s grand-uncles. Meirel was a mine of information regarding the Bennett’s ancestry in Ireland but believed she could put me in touch with a lady in San Francisco who was a much closer descendant than herself. Barbara Bigg’s grandfather and Arthur Bennett’;s grandfather she told me were brothers. The best part of contact with Barbara however was that in the course of her research of her family tree, she had been in contact regular with a New Zealander, Arthur Godfrey Bennett’s niece, Bobi Comrie-Carswell and who Barbara put me in touch with – Strike 3 … Home Run!

So, after a virtual circuit of the globe piecing together the Bennetts from Tipperary and Connecticut, USA (Bennett family members emigrated to both Australia and Connecticut USA in the 1910s after John and Miriam’s house in Tipperary was burnt down and their lands confiscated during a period of unrest between the Irish Protestants and Catholics), I was back in NZ, and emailing Bobi Comrie.

Bobi Comrie is William Henry Bennett’s second eldest and second daughter. She has an older sister Linda and two younger brothers, Paul and Anthony. Bobi is the Bennett family’s genealogist and who has researched the family extensively and as such, was also able to confirm that the Bennett families I had been attempting to contact in Temora NSW, were of no relation as her father had died at Temora in 1993 – all of his children and their families lived in New Zealand.

Coincidences just keep coming …

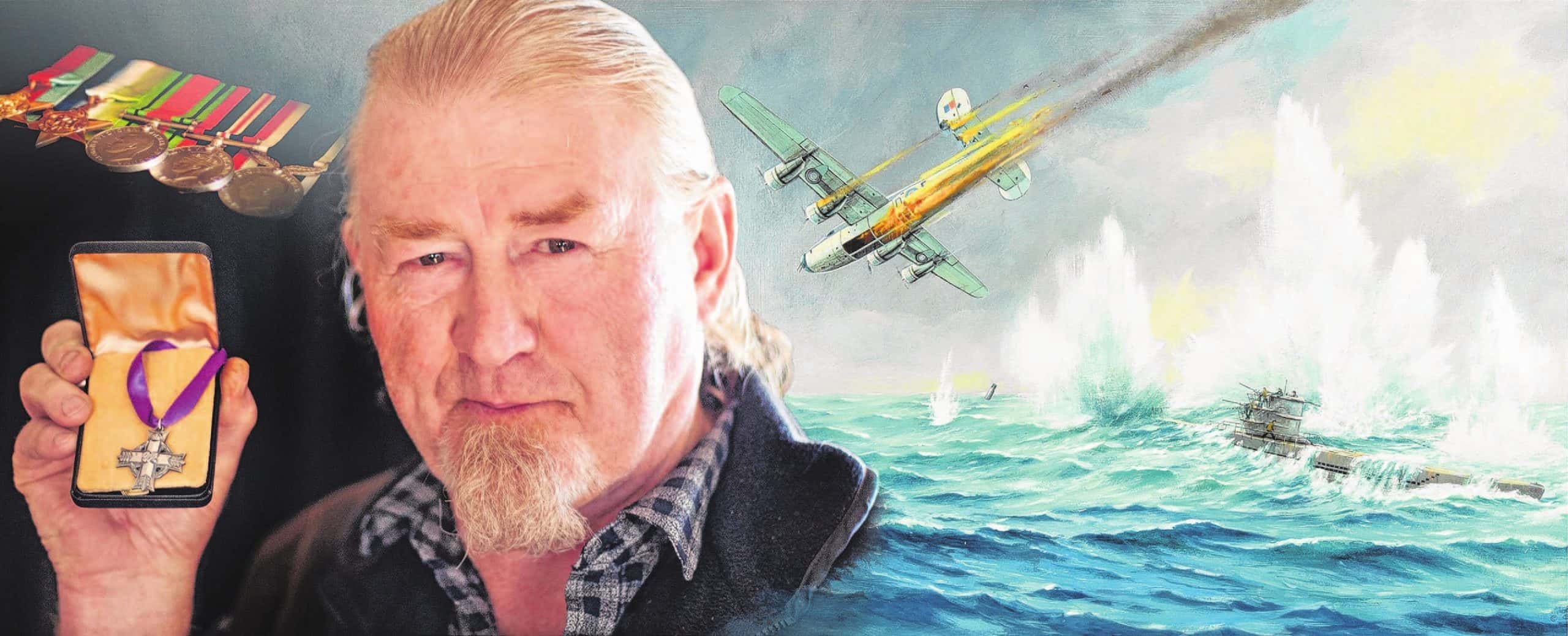

My preference is to return family medals to male members of a family who still carry the surname of the deceased service person named on the medals, and so was grateful to Bobi for putting me in touch with her brother Paul Arthur Russell Bennett in Alexandra, West Otago. I contacted Paul and told him the story of Arthur’s Memorial Cross and how I had arrived at the decision to return the Cross to him. Paul was thrilled at the prospect as he had been named after his famous uncle Arthur which would make the return of the Cross extra special to him …. and then he told me his story which revealed the most amazing coincidence I could never have imagined.

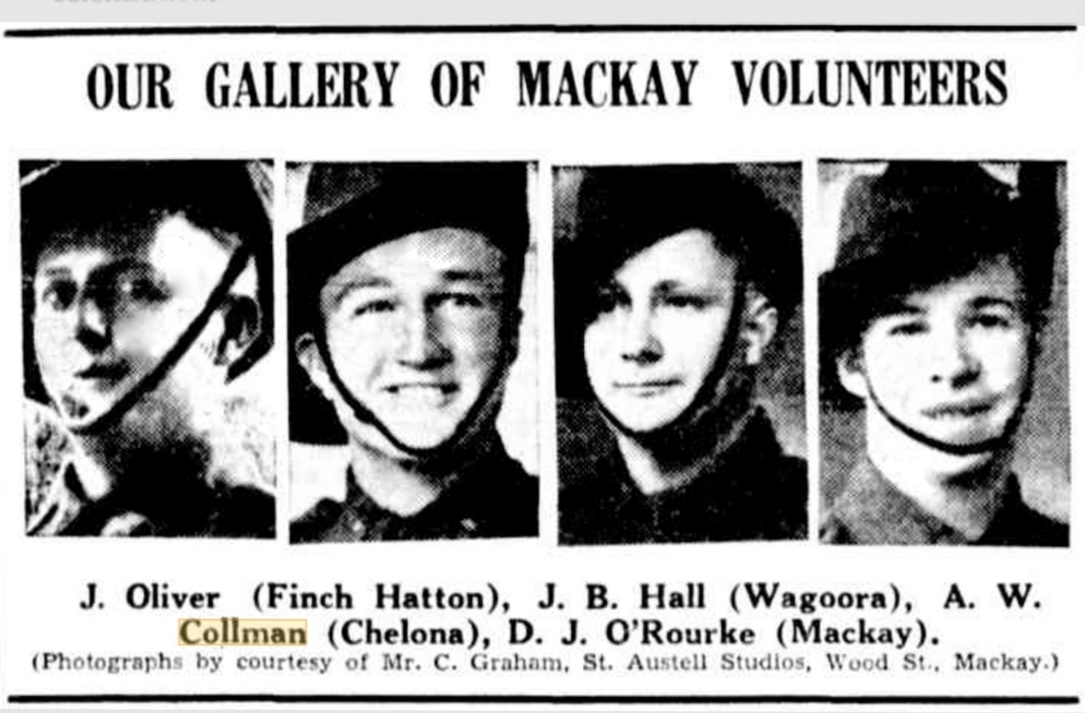

Paul told me that in the 1990s he moved to Queensland and lived at MacKay for about 10 years (in Evans Street to be precise). After a decade in Australia Paul was in the midst of making arrangements to permanently return to NZ when he received a surprising phone call from sister Bobi back in New Zealand. Bobi’s genealogy research of the Bennett family had turned up a long lost aunt that her generation of the family had never met. Aunt Mary was Mary Lavinia Maud Bennett, the youngest sibling of Bobi and Paul’s father William Henry and their uncle Arthur Arthur Godfrey Bennett. According to Bobi their Aunt Mary had also lived in Mackay for considerable period of her life, not as a Bennett but as a COLLMAN. When Bobi called Paul it transpired that Mary Collman (by then a widow) was in fact living in the very same street as Paul – No 61 Evan Street, Mackay! No 61 was barely 200 meters from Paul’s house on the opposite side of the road, the address of a local Retirement Home.

The lost Scroll (and medals?)

Mary Bennett had grown up in Upper Hutt and had worked as an ANZ Bank Teller in Upper Hut and Wellington City branches for the best part of 20 years. I recalled tracing Mary Bennett’s movements (which were few) during my initial research but had lost sight of her around 1960 when at the age of 32, and still a Bank Officer, she was living with her widowed grandmother Miriam Bennett in McCurdy Street, Silverstream. After Miriam Bennett died, with no family remaining in Upper Hutt, Mary must have decided to return to the land of her and her siblings birth, eventually ending up in Mackay, Queensland.

Paul said he cautiously made contact with Mary, a lady in her late eighties who understandably was initially very suspicious of this fellow who suddenly appeared out of the blue claiming to be related. All reservations Mary had were soon dispelled as Paul unravelled what knew of his family, and those he didn’t know (which included his father William Henry). Thereafter Paul had made regular visits to his newly found Aunt who over time was able to fill gaps in Paul’s early life of which he had little or next to no knowledge of. Mary also gave him one of her many treasured photo albums that contained a few pictures of his father. Proud of her older brother Arthur’s wartime exploits, Mary related to Paul the story of Arthur’s death in the Liberator at sea, the first time he had ever heard that Arthur was a relative. The final revelation was that Paul’s second name “Arthur” had been deliberate in honour of Arthur Bennett’s memory.

Mary did eventually marry in Australia. Her late husband was also named Arthur, an ex-WW2 digger, QX18694 Private Arthur William COLLMAN (1914-1981), 2/3rd Australian Pioneer Battalion and a farmer from Chelona in rural Queensland.

Sometime after Paul returned to New Zealand his 91 year old Aunt Mary Collman began to fade and so Paul decided to return to Australia once more to visit her. Unfortunately Mary had passed away before Paul arrived, a former neighbour of Mary’s informing him of the details on his arrival in Mackay. Mary’s neighbor also told Paul his aunt’s personal possessions, photographs albums, keepsakes and family treasures she had cherished and preserved over the years, had all been disposed of. The neighbor however had managed to salvaged the only item that had been left behind after Mary Collman’s room at the rest home had been emptied after her death …. a framed Memorial Scroll issued in the name of F/Sgt. A. G. Bennett. The Scroll was issued by the NZ government on behalf of King George VI to the Next of Kin of every sailor, soldier, airman or nurse who made the supreme sacrifice during World War 2.**

When Paul told me he had Arthur’s Memorial Scroll I could hardly believe my ears! Of all the things to have been found of his Aunt Mary’s possessions, that original Scroll had once accompanied the Arthur’s Memorial Cross! Both items were sent to Arthur Bennett’s mother Miriam (Paul’s grandmother) after the death of her son. This was one of these ‘one in a million‘ circumstances that rarely occurs, that the Cross and the Scroll should be reunited after being separated under unknown circumstances, who knows when?

This coincidence led me to conclude that Paul’s Aunt Mary, being the youngest of Arthur’s siblings, had most likely been in possession of all of Arthur’s memorabilia including his medals. Originally in Miriam Bennett’s possession, Miriam had lived with her daughter Mary at Silverstream until her death. Naturally Mary being the only known relative at the time, would have inherited her mother’s personal effects which she would have taken with her when she emigrated to Australia, only to have them pilfered or dumped it would seem after her death. Sadly, this is not an uncommon circumstance for those in residential care.

For Paul Bennett the added bonus for him was that his Uncle Arthur’s Memorial Cross was the only medal that was named before it was issued. Apart from gallantry medals, all World War 2 campaign and service medals issued to New Zealanders after the war were un-named, unlike those issued by Australia and most other Commonwealth countries which were all named, except Britain. This of course meant that there would also be no chance of ever recovering Arthur’s original medals sent to his mother.

Reunited …

Satisfied with my conclusions, I made arrangements to personally deliver this unique and special Memorial Cross to Paul. Given Arthur’s original medals were lost forever, MRNZ replaced his medal entitlement with a duplicate group of genuine and original campaign medals to accompany the Memorial Cross, expertly mounted by my MRNZ colleague Brian Ramsay.

On June 8th I made the eight hour drive from Nelson to Alexandra with the Cross and medals on their final journey to be reunited with Arthur Bennett’s nephew, Paul Bennett. The handover was a humbling and emotional moment as we reflected on the fate of Arthur and the other crew members, what was happening inside the aircraft during the attack, and of their ultimate loss. It was also a chance for Paul to clarify and reflect on a number of unspoken events which had impacted upon the lives of the Bennett family, not the least of which was Arthur’s loss at such a young age. The notoriety that surrounded the award of the Victoria Cross to aircraft captain F/O Lloyd Trigg in many ways over time has rendered the contribution and memory of Arthur Bennett and his fellow Liberator crew members almost anonymous. Whilst Lloyd Trigg’s name is forever linked with the gallant attack on the submarine that saw him awarded the VC, the names of his crew members whose lives were also sacrificed, regrettably were not themselves rewarded in some small way for their contribution, and supreme sacrifice. Lest We Forget

Read the ODT story here: https://www.odt.co.nz/regions/central-otago/return-medals-brings-links-family-war-story

My thanks to Tom Ireland (President, QLD RAAF Assn.) for bringing the Memorial Cross to light and sending it to MRNZ, a significant family keepsake and a piece of New Zealand’s illustrious military aviation history that may have been lost forever. To Bobi Comrie, my thanks for her assistance in clarifying the family linkages and introducing me to her brother Paul Bennett. Both Meirel (UK) and Barbara (San Francisco) were also vital links in the world-wide Bennett chain that eventually linked me to Bobi. Last, my thanks to Shannon Thompson (West Otago News, Alexandra) for her coverage and accompanying video of the return of Arthur Godfrey Bennett’s Memorial Cross.

The reunited medal tally is now 412.