16586 ~ RONALD GORDON HAY-MACKENZIE

Hay-Mackenzie is a name associated with early Otago from the 1840s, and later with Westport from 1897 to the present day.

Like friendly societies, volunteer fire brigades, military units and bands, the lodge played a vital role in the social and business life of the colonial male. Tertius Hay-Mackenzie (1846-1906) was a 26 year old Clerk living and working in Oamaru when he was initiated into the local Masonic lodge, Lodge Waitaki IIII E.C. on 27 Oct 1871. Here Tertius would make many useful contacts in the business world of early Oamaru, in particular those men connected with the forthcoming railway system. Tertius and his wife Margaret MACKENZIE (1851-1919) from Migdale, Creich in Invernesshire, were living in Oamaru when the south Island railway line system was initiated as part of trans-South Island link from Picton to Bluff. The portion of the line between Oamaru and Timaru was started from each end to link somewhere in the middle. No doubt Tertius viewed the coming of the ‘iron horse’ with not only a degree of fascination but also as having the potential for long term employment.

The fledgling southern Main Line South had started with the construction of the Christchurch to Dunedin line in 1865 that would eventually connect Lyttelton with Invercargill. The Main North Line from Christchurch to Picton was started simultaneously in the 1870s however due to the rugged east coast terrain that had to be negotiated, it became one of the longest building project in New Zealand’s history, spanning both world wars and the Great Depression. As Dunedin grew rapidly grew from the wealth being poured into it from the goldfields, other outlying regional centres began to be established. It was clear a reliable rail system would best serve the needs of these by being able to move large amounts of materials, fuel, animals and people to and from the ports at Lyttelton, Timaru, Chalmers and Bluff. The Dunedin to Port Chalmers line was opened in Jan 1873, followed by lines to Gore, Balclutha and Oamaru opening in 1875. The link between Christchurch, Timaru and Oamaru was completed by 1877 and the line through the very difficult terrain between Oamaru and Dunedin, was finally opened in 1878.

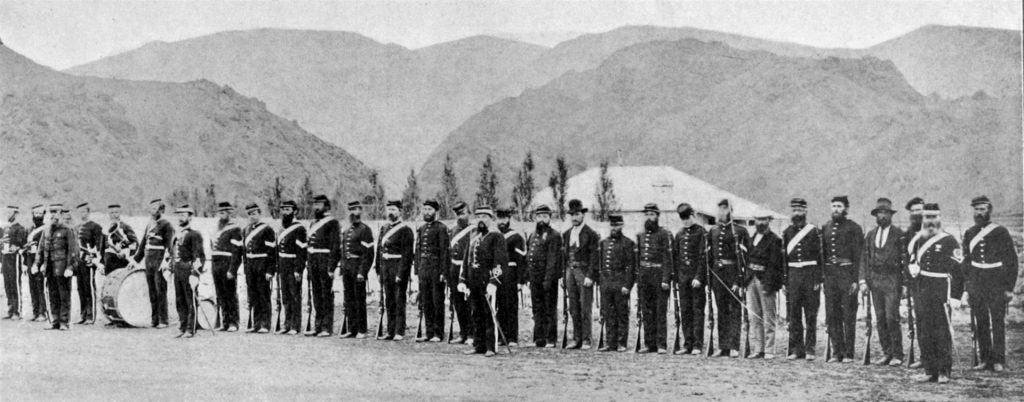

Tertius Hay-Mackenzie at this time had also been active in the local Militia that every major population centre had raised for the protection of settler population against the threat of marauding natives. While there had been few incidents in Otago, some of Te Rauparaha’s Ngati To militant ‘generals’ had other ideas as they perceived the Kai Tahu as being too willing to integrate with the local pakeha whaling and settler community. With murder and the desire to wipe out both the Kai Tahu pakeha around Otago harbour on their minds, a war-party of 70-80 tribesmen set forth in 1836 over land, down the Westland coast into NW Otago to inflict a surprise attack. A surprise attack it but not as the war party had planned since word of their coming had preceded them. The problem was the key chiefs were on some of the off-shore islands where they had been working and gathering food. With the assistance of substantial firepower in the form of musket and cannon, the Otago Kai Tahu were ferried to the mainland by the local whaler and ferrymen, just in time to inflict a comprehensive defeat on Te Rauparaha’s unsuspecting invaders. They were soundly defeated and never returned. This was the last ever attack on the Kai Tahu and Otago settler communities. Within nine years Imperial Army regiments were established in the North Island which became a catalyst for the start of the Land Wars in 1846 and lasted until 1872. The upshot of the sporadic attacks which had occurred country wide was the was establishment of localised Militia units of settlers, trained and commanded by regular Imperial Army officers and NCOs, for the protection of settlers and their property.

Tertius H-M was 36 years of age and a keen supporter of the local Militia. In March 1873 he had been commissioned as a Sub-Lieutenant in the 3rd Otago Rifle Volunteers, and the following year was appointed the unit Adjutant.

In 1875 Tertius entered the Government’s employ with the NZ Railways Department. In Jan 1876 he was given charge of the recently constructed Waitaki North railway station near Oamaru, being appointed its Stationmaster. From 1880 to 1896 he successively filled appointments of Stationmaster at Moeraki Junction (now Hillgrove) and at Palmerston (Otago); he was a relieving officer at Dunedin; Officer-in-Charge of the Waimea Plains railway (Gore to Lumsden), and Station & Postmaster at Stirling. A short posting to Bluff as Stationmaster in 1896 preceded his appointment as Stationmaster-in-Charge of Traffic on the Westport section of the Government railways.

The Westport Railway Station was the centre of extensive rail traffic, with a traffic staff consisting of the Stationmaster-in-Charge at Westport, two other stationmasters, four clerks, five cadets, four foremen, six guards, two signalmen, three tablet porters, twelve shunters, porters, and storemen, a crossing keeper and night-watchman; the total number employed on the section under Mr. Hay-Mackenzie was forty-one.

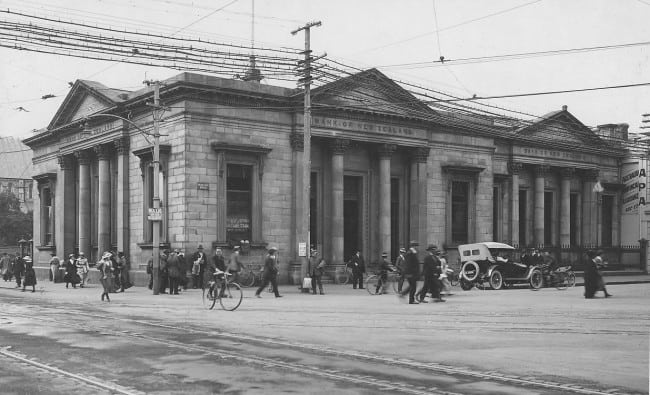

Tertius’s wife Margaret meanwhile, had been rearing their family of seven children – Ronald Charles Robert Meek Hay-Mackenzie (1871-1943)** had remained in the south when the family moved, having started his banking career as a clerk with the BNZ in Stuart Street, Dunedin. Flora Isabella was born in 1876-1908, Albert Alexander [snr] (1880-1944), Lilla Mary (1882-1948), Ethel Anne (1885-1942), Gordon** (1885-1930) and finally William Ewan Mackenzie (1906-1996). A committed and hard working servant of the NZ Railway Department, Tertius Hay-Mackenzie died in 1906 shortly after his last son was born – he was just 60 years old.

Notes:

** SA-2691 Sergeant Ronald Charles Hay-Mackenzie – 5th Contingent, NZ Mounted Rifles (NZMR)- a BNZ bank officer, served in South Africa during Anglo-Boer War 1901 and was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with Clasps: TRANSVAAL, CAPE COLONY, RHODESIA, ORANGE FREE STATE.

** SA-2691 Lieutenant & Paymaster Ronald Charles Hay-Mackenzie – 8th Contingent, NZMR – returned to South Africa in Jan 1902 for eight months as a Lieutenant and Paymaster for the 8th Contingent. The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on May 31, 1902 bringing the war to an end. For this service he was awarded two further Clasps to his QSA medal: SOUTH AFRICA 1901, and SOUTH AFRICA 1902.

** Gordon Hay-Mackenzie married Agnes Genevieve SWANN, QSM who was born in Levuka, Lomaiviti, Fiji in October 1897, the daughter of a Yorkshire ship’s doctor and a Samoan national. Gordon and Agnes made their home in Western Samoa and had a family of four. After Gordon died in 1930 Agnes re-married Charles Morton Grey of Auckland. and together they launched the Grey Investment Group. Known to one and all as Aggie, her forte was hospitality. In 1933 she founded the internationally renowned “Aggie Grey’s”, then a one-time burger joint and bar for American GIs on R&R during the war. Aggie’s sister Mary Croudace also ran a boarding house in Apia called “The Casino.” Unfortunately Charles died midway through WW2 in 1943 leaving Aggie to develop the business alone. Aggie herself became very popular and was well known for her warmth and hospitality. She was in her element in hospitality; the bar became a tourist hotel its patrons loved because of its laid back atmosphere, presided over by a fun-loving Aggie. Aggie Grey’s become famous for the high profile guests who stayed during and after WW2 which included film stars, millionaires, Broadway producers, authors (James A. Michener), politicians and high ranking military men. The hotel became a mecca for tourists after the war and remained in family hands even after Aggie’s death, to be run buy her son Alan. Agnes “Aggie” Grey’s success has been reflected in two biographies written of her, she has featured on several Western Samoa postage stamps, and was awarded New Zealand’s Queen’s Service Medal in 1983 for services to tourism. Aggie continued to run her ’empire’ until her death at 90, in 1988.

The hotel was completely wrecked in a 2012 cyclone and as a consequence was sold by Alan in 2013 to the Sheraton hotel chain. Sheraton completely rebuilt the iconic hotel. Sheraton Aggie Grey’s has evolved into three resorts, two in Samoa and one in Tahiti. Sheraton sold the original (re-built) “Aggie Greys” Apia in 2018 to Chinese investors for NZ$50m.

Westport

Albert Alexander Hay-Mackenzie (snr) had followed his father Tertius into Government service with NZ Railways and became an Engineer (engine driver). His name-sake son Alex became a Fitter with the NZ Railways.

Albert (snr) had married Westport girl Amelia Philomena PAIN (1880-1977) in 1906 and together the couple made their home in Wakefield Street and raised a family – Agnes Dorothy (1900 – ?), Albert Alexander [Alex, jnr] (1901-1994), Catherine Margaret (1906-2001), Ronald Gordon (1907-1974), Henry Thomas (1910-1993), Flora (192-1978, James [Jack] (1915-1984), Therese Dorothy (1917-2006) and Lucie Pain Hay-Mackenzie (1923-1995).

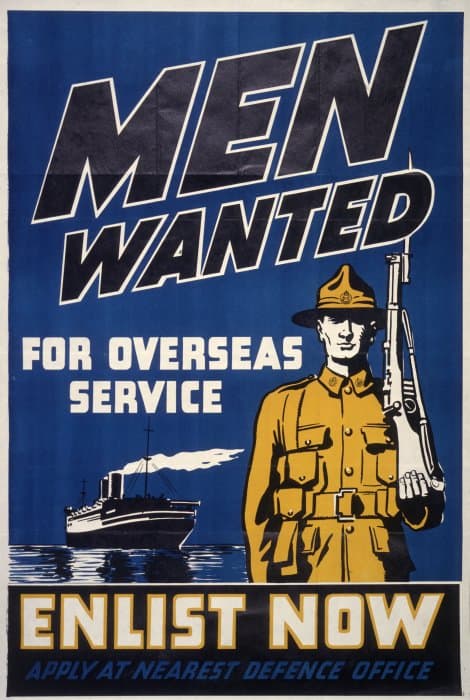

Born in Westport on 31 Oct 1907, Ronald Gordon Hay-Mackenzie was educated at St Bede’s College in Christchurch. As part of the national emergency preparedness regime, the 1900 Defence Act had introduced, thanks in part to enthusiasm generated by the South African War, voluntary military cadet training into secondary schools. An amendment to the Act in 1909 made military training compulsory for all boys from the year they turned twelve. This involved 52 hours of training each year as junior cadets. In 1912 the joining age was raised to fourteen. Accordingly Ron was ‘enlisted’ into the St Bede’s College Cadet Battalion in his fourteenth year. For many like him, this would be their only exposure to any sort of military training experience and life in uniform before they would find themselves conscripted for overseas service during the Second World War.

With the end of his secondary education looming Ron considered his employment options. While at St Bede’s he had proven himself a gifted mathematician and so, like his uncle Charles Ronald (Bank Officer) and great-uncle Gordon (Banker/Accountant) before him, Ron followed their lead and entered the finance industry as a junior bank officer with the Bank of New Zealand.

For those who can remember Cathedral Square in Christchurch circa 1960, you will probably recall the rather imposing concrete ‘block-house’ building in the SW corner of the Square adjacent to the United Services Hotel. It was at this BNZ branch that Ron started his banking career as a junior teller in 1932 (as it happens, the same time my own mother was employed as a teller in this bank! – I will forever wonder whether they ever met?). Over the ensuing seven years Ron spent time at BNZ branches in Mataura (Wyndham) and in Auckland City. As the spectre of a war in Europe started to rise and the country took on a level of concern reminiscent of pre-First World War days, Ron’s banking career looked as though it was about to came to a shuddering halt. As the re-introduction of national conscription became a hot topic, Ron had already volunteered for overseas service so would not be caught up in the public outcry that would invariably follow any decision by the government to re-introduce conscription.

Conscription & 2 NZEF

Following the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the New Zealand government authorised the formation of 2 NZEF (the Second NZ Expeditionary Force) for service abroad. Following consultation with the British government, it was decided that the main New Zealand contribution to the war effort would be in the form of an infantry division, the 2nd NZ Division, under the command of Major General Bernard Freyberg. The new Division, comprising three Brigades, would require nine battalions of infantry. Several infantry battalions were formed from 1939 to 1940 with New Zealand volunteers and when ready, would be transported by sea in three Echelons (contingents, tranches etc) of men, equipment and supporting arms, to their destination.

All able bodied men aged between 19 and 45 became liable to be called up by ballot. Prior to this, eligible men who had volunteered for service were able to submit a preference of which arm of the service the wished to join, e.g. to serve in either the Navy, Army or Air Force. Once conscription was imposed volunteering for Army service ceased from 22 July 1940, although entry to the Navy and Air Force remained voluntary until 1941. With effect from 31 July 1941, all married men in unreserved occupations were called up for military service. From January 1942 workers could be man-powered or directed to essential industries within New Zealand.

Note: ** The Battle of France, a campaign that began on May 10th, 1940, and ended with German forces invading France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, was a major disaster for the Allies who lacked a back-up plan, communicated poorly, and left themselves exposed by leaving gaping holes in their defence.

The Labour Party had traditionally opposed conscription on the grounds that volunteer forces would be able to cope with all contingencies. Several Labour politicians who had been imprisoned for anti-conscription activities in the First World War were in cabinet when New Zealand entered the Second World War in 1939. As in that earlier war, volunteer numbers proved insufficient and in 1940 the National Service Emergency Regulations were passed to introduce conscription. All men aged between 19 and 45 were required to register for military service, and were divided into categories depending on their marital status, age and number of children. Maori were exempt from conscription, since a high proportion were willing to volunteer. The total eventually conscripted was more than 312,000.

Enlistment

In 1940 Ron was working in the BNZ branch at Wyndham when he received advice he had been balloted for service overseas with 2 NZEF and would be part of the Second Echelon for embarkation purposes. Ron Hay–Mackenzie was 28 years and 8 months of age when he returned to Westport to start his enlistment procedures. First was his completion of enlistment documentation at Greymouth after which he was directed to report to the King Edward Barracks in Cashel Street, Christchurch to be formally Attested and sign the dotted line. Once signed, Ron became contracted to the “King’s call to arms” for as long as might be required – the great unknown!

23 Battalion – Second Echelon, 2NZEF

It was January 1941 before Pte. Hay-Mackenzie (H-M) was required to report to Burnham Military Camp for two months of military indoctrination training and basic preparation for his infantry role overseas. When the training was completed, all troops were given “open leave” from March 8th which meant they could leave camp, go home and wait until they were called to re-assemble for embarkation of the transport ships at Lyttelton.

NZ 2nd Division ~ Order of Battle

HQ NZ Division

- 27 NZ machine Gun Battalion

- 5 NZ Field Artillery Regiment

No 4 Brigade

- 18 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 19 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 20 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 1 Light Troop (Royal Artillery)

No 5 Brigade

- 21 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 22 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 23 NZ Infantry Battalion

- 28 (Maori) Infantry Battalion

- 7th Field Company NZ Engineers

- 19th Army Field Corps Company

- NZ Field Punishment Centre (FPC) – prisoners were released to fight

- 1st Greek Regiment (1,030 Officers and men),

- Evilpidon (Greek) Offrs Academy (17 Officers, 300 Cadets)

- NZ Divisional Cavalry

- NZ Composite Battalion (700 rifles)

- 6th Greek Regiment (1,389 Officers and men)

- 8th Greek Regiment (840 Officers and men)

Battle of Britain – 1941

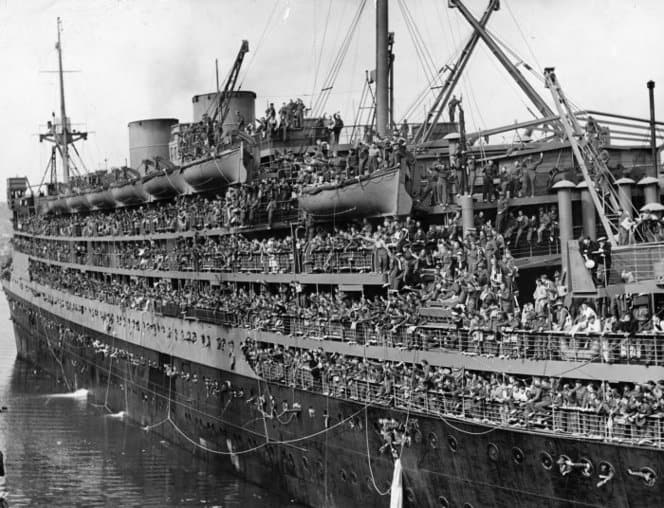

On 24 March 1941 Pte. Hay-Mackenzie was promoted to Temporary Lance Corporal (Temp. L/Cpl) in advance of 23 Canterbury Battalion’s embarkation of the troop transport ship RMS Andes, a brand new P & O passenger liner, which was scheduled to start embarkations on 7 Apr 1941. After a series of operational delays the ship left Lyttleton on 2 May and headed north to Cook Strait. Here it joined with Aquitania, Empress of Britain and Empress of Japan carrying soldiers who embarked at Wellington. Together with their escort ships, HMS Leander and HMAS Canberra, the convoy made its way via Melbourne adding several more ships to the convoy and making for Fremantle.

The convoy joined with others waiting at Fremantle and were subsequently arranged into a series of fast and slow convoys in preparation for travel with a their escort of escorts to Egypt. The Andes made port Cape Town, and Freetown. Originally destined for the port of Alexandria via Aden and the Suez Canal, the deteriorating situation in Europe had convinced the British Government to divert the convoy to the South Atlantic, via Capetown, to Scotland! Here the 2nd Echelon would both train and be part of the Battle of Britain defence against the threat to Britain of invasion.

Andes was five days from its destination when L/Cpl H-M incurred the wrath of his superiors. His record simply states that he “Neglected to Obey Ship’s Standing Orders” – the result was a formal charge heard by his Commanding Officer which resulted in his Lance Corporal stripe being removed. Ron was once again Private Hay-Mackenzie.

The convoy reached Scotland without any holdups and anchored in the Clyde River in June 1941. Following disembarkation the troops entrained at Edinburgh for the long journey to southern England, marching for the last few miles to their tented camps at Aldershot.

The Second Echelon Infantry battalions (22, 23, 24) trained and exercised over and over under the NZ Divisional Commander, General Freyberg’s critical eyes, in order to minimise the errors identified during the operations conducted by the First Echelon battalions (19, 20, 21).

Following the training, the battalions spent the remainder of the year on garrison duties in the south of England where they were positioned to respond to an anticipated cross-Channel invasion by the Germans in the wake of the fall of France. Their task however was severely hampered by the lack of new weapons, there was no ammunition and no transport for the Kiwis, all of which was supposed to have been supplied by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The BEF had lost everything when France fell as a result of their frantic evacuation from the beaches of Dunkirk 26 May – 4 June 1940. The much anticipated cross-channel invasion, fortunately, never came.

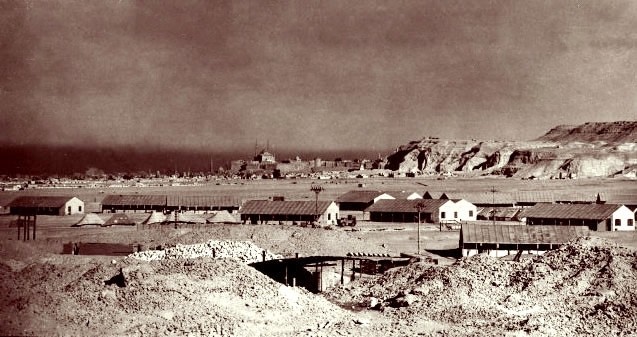

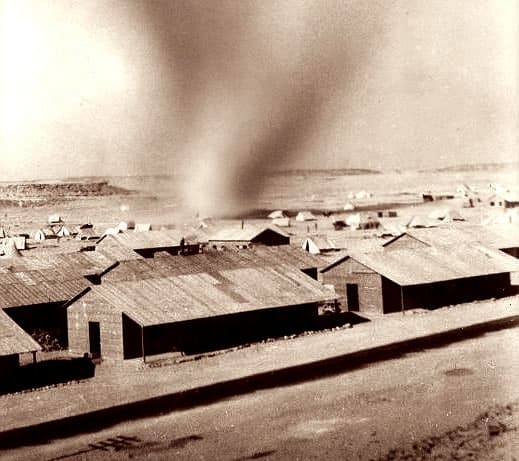

2nd NZ Division’s Camp, Maadi

The Second Echelon left the UK on the Athlone Castle, disembarking at the port of Alexandria, Egypt on 15 May 1941. The battalions were moved by train to Cairo and then marched to the 2 NZ Division’s Maadi Camp, 14 km to the south of Cairo.

The First Echelon had arrived in Egypt in March 1940 and the Third Echelon at the end of Oct 1940 which completed the concentration of the Division ahead of its deployment to northern Greece in April 1941. Meanwhile the remainder of the 8th Army units (the NZ Division was one of seven in the 8th Army) were heavily committed to the North African campaign in Libya, around Tobruk and El Alamein.

The 23rd elements were sent into Greece in May 1941 to reinforce a defensive line established by the Allies in an attempt to stem the German advance through Greece, the prize being Athens.

Operation MARITA – Greece

Following the Italians’ invasion on 28 October 1940, Greece repulsed the initial Italian attack and a counter-attack in March 1941. When the German invasion, known as Operation Marita, began on 6 April, the bulk of the Greek Army was on the Greek border with Albania, then a protectorate of Italy, from which the Italian troops had attacked. Germany invaded from Bulgaria, creating a second front. Greece received a small reinforcement from British, Australian & New Zealand forces in anticipation of the German attack. The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its effort to defend against both Italian and German troops. As a result, the defensive line did not receive adequate troop reinforcements and was quickly overrun by the Germans, who then outflanked the Greek forces at the Albanian border, forcing their surrender by April 9.

The 8th Army Commander, General Bernard Montgomery, reluctantly gave the order to withdraw the Allies from Greece and so began the withdrawal of 40,000 troops from the country to Crete began. The NZ forces fought a rear guard action against the invading German forces all the way to the Mediterranean. The Germany Army had reached the capital, Athens, on 27 April and Greece’s southern shore on 30 April, capturing 7,000 British, Australian and New Zealand personnel and ending the battle with a decisive victory.

The last New Zealand troops left Greece by 29 April having sustained losses of 291 men killed, 387 seriously wounded, and 1,826 men captured in this campaign.

The conquest of Greece was completed with the capture of Crete a month later. Following its fall, Greece was occupied by the military forces of Germany, Italy and Bulgaria.

Operation MERCURY – Crete

Ron’s 23 Battalion had been dispatched to Crete soon after their arrival in North Africa to bolster the allied troops that had already established a significant presence on the island. The evacuated POWs from Greece quickly soaked up the spare capacity for medical care and food supplies. On the morning of May 20th 1941 Nazi Germany began an airborne invasion of Crete, most of whom were paratroopers and mountain forces, normally reckoned as elite units. It was also the first time paratroopers had been used en mass as a primary invasion force. The fighting was intense and much of it at close quarters and casualties on both sides were significant. Greek and other Allied forces, along with the Cretan civilians, tried desperately to defended the island. After one day of fighting, the Germans had suffered heavy casualties and the Allied troops were confident that they would defeat the invasion. The next day despite a gallant attempt to defend Maleme Airfield, it was taken which allowed an unopposed German reinforcement landing by sea.

The Allied forces put up a tremendous fight over the next seven days, particularly 28 Maori Battalion who inflicted a savage toll on the enemy, but superiority in numbers with Stuka air support, forced the Allies into a fighting withdrawal across the White Mountains to the south coast port town of Sfakia where they were to be evacuated by the Royal Navy. A shortage of available ships meant there were on five made available, insufficient to rescue everyone from Crete. More than 57,000 were evacuated however not without further casualties that resulted from Stuka dive bomber attacks. Some sustained bomb damage and caused casualties on other. One ship was sunk with a large loss of life.

Casualties during the 10 days of fierce fighting on Crete had been high on both sides, high enough that the Germans never again attempted this sort of airborne attack. It is said that 23 (NZ) Battalion was one of the most active and successful units from NZ, though they also had one of the highest casualty rates.

After the last RN rescue ship departed from Sfakia on 1 June 1941, there remained on the island some 5-6000 Allied soldiers (NZ, Aust, UK) who became Prisoners of War. The 2,180 New Zealand soldiers left at Sfakia were simply told they had little option but to surrender – the most NZ soldiers ever taken prisoner in one campaign. Pte. Hay-Mackenzie had been in the field with 23 Battalion for just over five weeks when he became one of those left at Sfakia. Although he didn’t know it at the time, Ron was about to spend the next four years of his life as a Prisoner of War.

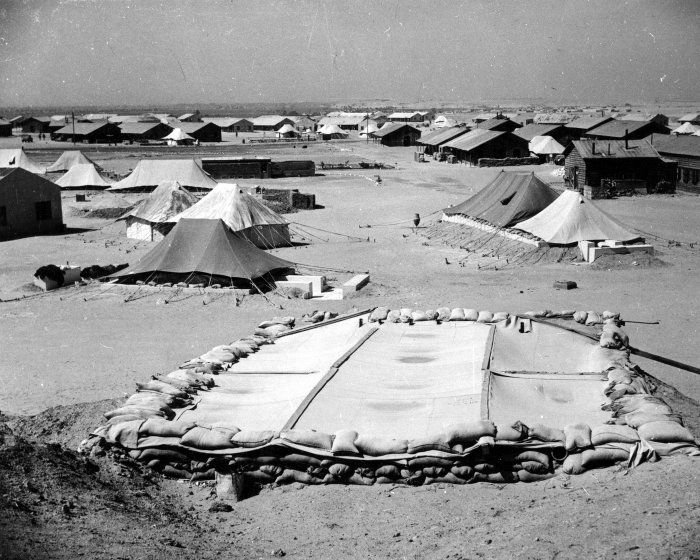

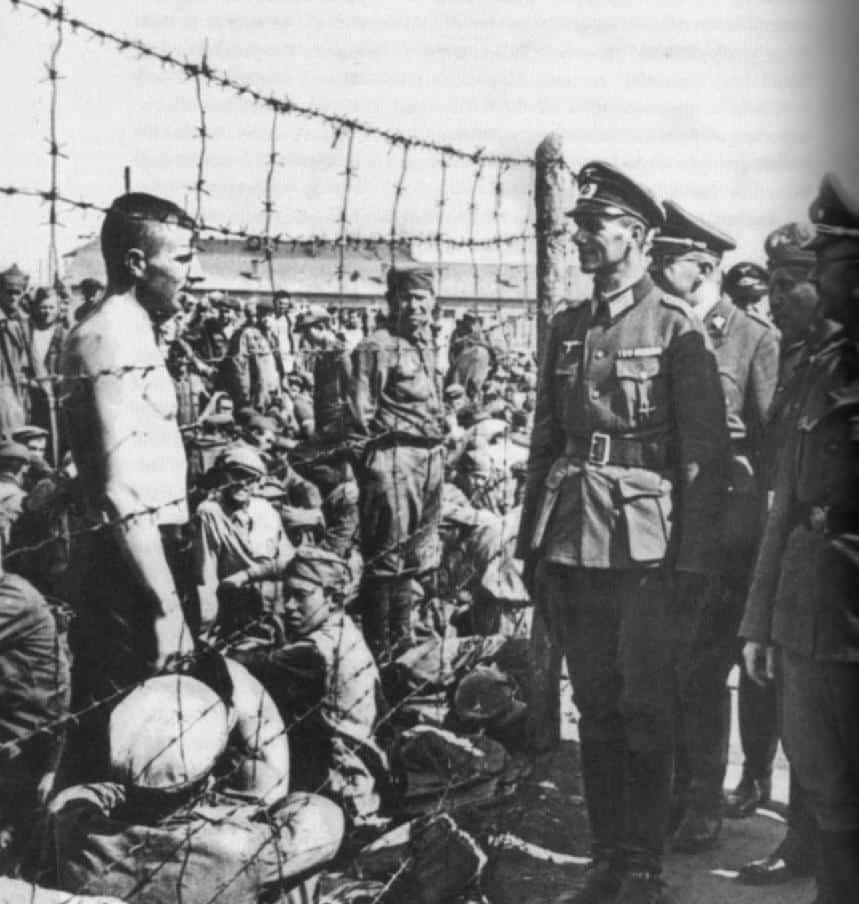

“Dulag Kreta”

Prior to the surrender, over 300 NZ soldiers had taken their chances and escaped into the hills to join with the Cretean resistance while others attempted, some successfully, to make their way back to Egypt. In total, 2180 NZers had been made Prisoners of War. The NZers at Sfakia once captured were searched and all papers, steel helmets, possible weapons, and occasionally valuables were taken. They were then force marched in groups of 200 back over the White Mountains that necessitated a climb of between 1500-3000 feet to get through the pass and down towards Souda Bay and Galatas, the location of the POW transit camp known as ‘Dulag Kreta’ (Transit Camp Crete) or “Galatas Camp” to the Allies. The distance from Sfakia was about 15 kilometers. The march to get to the camp in itself was an arduous journey in the scorching sun on dusty roads, particularly for the many injured and wounded, and others with sickness starting to afflict them. Some died along the way.

The POW compound had been set up at the former location of No 7 (British) General Hospital, west of Canea near the Maleme Airfield. The hospital had been bombed and machine-gunned from the air on 20 May 1941, and then overrun by German paratroopers in spite of the large red crosses laid out on the ground around the hospital (in direct contravention of the Geneve Conventions of which Germany was a signatory!). The Germans drove out the patients who were able to walk, herded them and hospital staff into the nearby area of 6th (NZ) Field Ambulance and later marched their captives to the ‘Dulag Kreta’.

Once in Dulag Kreta, the poor food, overcrowding and insanitary conditions produced a crop of scabies and dysentery. These cases and others of malaria, poliomyelitis together with prisoners wounded by trigger-happy guards, kept the five makeshift hospital wards that had been hastily set up inside the camp, filled to capacity and their staffs continually occupied. The sick and wounded from the various German field ambulance and dressing stations, together with the medical staffs, were also brought into the camp. Unusual as it may seem, by 5 June approximately 1,200 Allied wounded and sick officers and men who were hospital cases had been flown direct to Athens for medical care.

POWs who were able bodied were put to work by the Germans to clear and repair Maleme Airfield and/or were used as human shields to deter British naval gunfire and air attack. Rations were insufficient to keep the men healthy, and for some weeks the guards winked at prisoners’ leaving camp to get fruit and other food nearby while also allowing Creteans to bring basket-loads to the camp fence. Authorised foraging parties too were allowed to bring in rice and other supplies from British dumps. When the German food supply became more regular, the prisoners’ daily meals evolved into a cup of porridge or rice, a cup of bean stew, and two-thirds of a pound of sometimes sour and mouldy bread. With such a meagre and monotonous diet, it is perhaps not surprising to find men boiling up bird-seed and finding it good to eat, or fighting for food at the camp fences, scavenging in rubbish heaps for any discarded scrap, be it mouldy bread or other, discarded as unfit for human consumption. Beyond the daily fatigues of the camp, there was little for men to do but sleep during the day unless they had drawn a place in one of the German burial or working parties.

Frontstalag 183 – Salonika

A spate of escapes from the ‘Dulag Kreta’ in June 1941 accelerated the evacuation of POWs from Crete to more permanent camps on mainland Italy and Germany. For some POWs this necessitated a two stage move; the first was by ship to another POW transit camp in Greece, and the second, a move by rail, road and on foot to a permanent camp in Italy, Germany or both.

Pte. Hay-Mackenzie had spent his last two months on Crete in the ‘Dulag Kreta.’ Together with the bulk of NZers he had been interned with, they were removed to the Salonika Transit Camp in Greece in October 1941 before being removed to Greece a permanent camp in Italy.

POWs were systematically crammed below decks into filthy cargo ship holds with little food or water, and having to endure oven like heat during the nightmarish four to five day voyage to Frontstalag 183, the Salonika Transit Camp located at this port town (Thessalonika) in northern Greece. Considering that a large number of the POWs were wounded, some with broken limbs, sickness and numerous other ailments, their trans-shipment to the substantial permanent POW camps on mainland Italy and in Germany must have been extremely arduous, particularly during the heat of high summer, or the extreme cold and snow of low winter.

All who had passed through Frontstalag 183 at Salonika, whether they stayed a month or two, or even just a day, remember this transit camp for its starvation diet, filthy conditions, the all too frequent shootings by the guards, the heavy labour under strict German guards, and also the badly equipped hospital. It was here that Pte. Hay-Mackenzie had his nose and teeth broken as a parting gesture by a belligerent German or Italian guard.

DR 442 P.W.

The process of capture ended with the POWs arrival at a permanent camp, the relative organisation and comfort usually came as a pleasant surprise to men whose expectations had been lowered by their treatment in the transit camps. Where the camp was located depended upon the war zone in which the POW was taken. For those who surrendered to German forces in Greece and Crete, the destination was Germany or German-occupied territory in central or eastern Europe. Men taken in the North African fighting however, were generally incarcerated in Italy (with the exception of a few airmen flown directly to camps in Germany).

In Italy and Germany a POW’s arm of service and rank determined the type of camp in which he was held. Officers were usually segregated in special camps. New Zealand airmen captured in Western Europe went first to an interrogation centre at Oberursel, near Frankfurt, and then to the nearby Luftwaffe transit camp, Dulag Luft.

Campo PG 85 – Italy

Upon his arrival at Campo PG 85, Pte. H-M was given the POW identity number DR 442 P.W. Campo PG 85 was an Italian prisoner of war camp on mainland Italy. The camp was positioned at Tuturano, about 100 km south of Bari, on the south-western inland coast of the Italian ‘heel’, due west of Brindisi. For Pte. H-M this meant another sea ‘cruise’ in the same style of ship used to get to Salonica. The POWs were taken to the port at Bari, and thence by road/rail south to Tuturano. After being advised in Nov 1942 that their son had been made a POW in Italy, Ron’s parents in Westport subsequently received confirmation from the Red Cross in Geneva that mail for DR 442 P.W. R. McKenzie could be addressed to “Posta Mil 3450, Tuturano, near Brindeisi.” This advice also stated Ron’s “health was good and treatment excellent” (yeah, right!)

When Italy capitulated in September 1943, there were more than 70,000 Commonwealth POWs in the country. After the camps were rapidly taken over by German forces, about 3200 New Zealand POWs were transported north into Germany, including Pte. Hay-Mackenzie since the number of prisoners being taken warranted space being made for more as they were rounded up by the German advance through Italy and Greece.

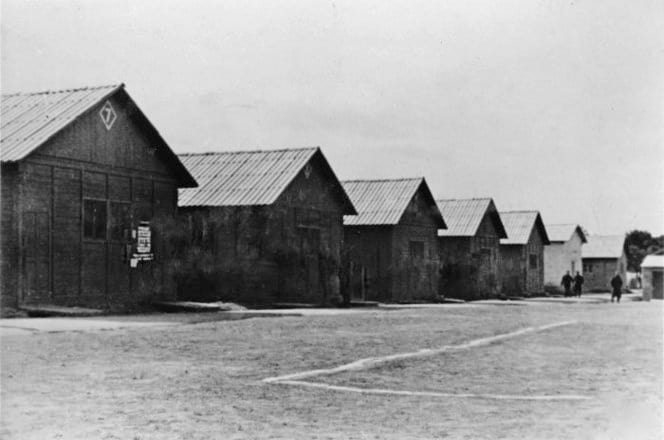

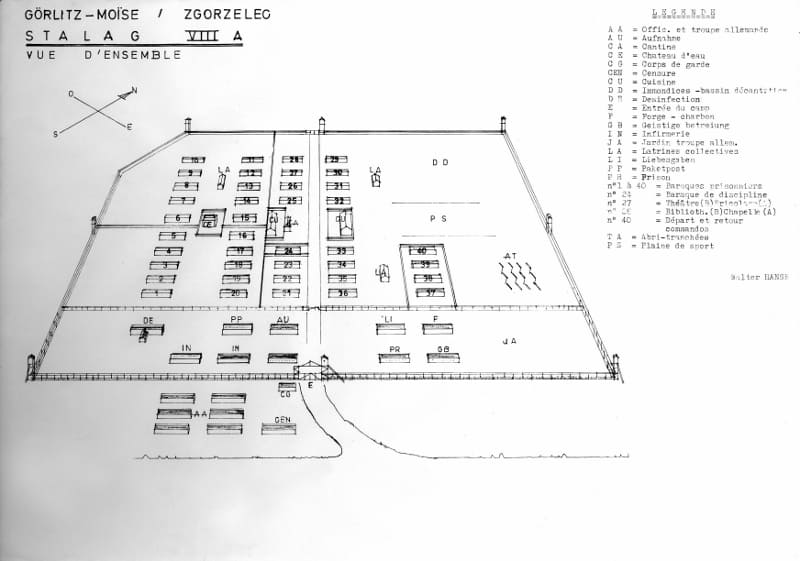

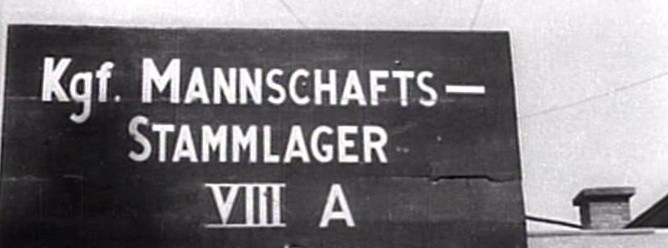

STALAG VIII A – Görlitz, Poland

In Dec 1943 Pte. Hay-Mackenzie was moved by train from Campo PG 85 to Görlitz, Lower Silesia in northern Germany.

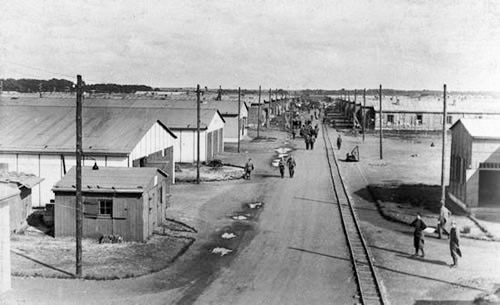

Originally built as a Hitler Youth camp with thirty barracks, the camp had been modified in Oct 1939 to house Polish prisoners from the German September 1939 offensive. It was the first POW camp in the Military District VIII Breslau (now known as Wroclaw, before the war it was part of the German Empire. It now sits inside the current borders of Poland). The camp was re-named Stalag VIII A Görlitz, one of three Stalag VIII (A, B & C) camps which held only Other Ranks prisoners (Warrant Officers, NCOs and men). Officers were interned in separate OFLAGs and separate facilities again were set aside as Interrogation camps.

The Polish prisoners had been employed in the building of further barracks at Görlitz each of which in the most dire of circumstances could house 500 men, 15,000 in total, and so when 40,000 French and 8,000 Belgian soldiers arrived over the summer of 1939 there was gross overcrowding and many were compelled to sleep outside in tents, with only the most primitive facilities available to them. By the end of Dec 1939 the Polish prisoners were transferred to the main camp in Moys, approximately 50 miles east of Dresden. The camp had grown to cover about 30 hectares. Fifty six barracks had been built, including two large kitchens, 14 of the barracks were reserved for the guards and the camp Command Post. The process of housing prisoners in the new barracks began in December 1939 and by the end of 1940 tented accommodation was no longer necessary.

It had been intended that Stalags VIII A, B and C would hold only prisoners of a specific nationality – Belgians, British and French respectively, however as time wore on the practicalities of doing this led to the plan being abandoned and the camps became very multinational in character. Overcrowding and living cheek by jowl became the norm. At one time Stalag VIII A held over 30,000 Soviet prisoners jammed into facilities designed for 15,000.

In 1943 2,500 soldiers from the battle in Italy, among them those from the British Isles, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa arrived in the camp. Prisoners in the surrounding Campos were also transferred to the Stalags, Pte-H-M among them. It was not until Dec 1943 that Ron’s family received word that P.W. 32882 (his Stalag identity number) had been moved from Campo PG 85 to Germany and interned in Stalag VIII A.

By September 1944 the British population in the camp had reached 1,300 with a further 2,000 or more working in the Kommandos (slave labourer details or detachments outside the camp). Specifically the British contingent was comprised of 470 British, 400 South Africans, 330 New Zealanders, 90 Australians, and a mix of others. Red Cross parcels had arrived regularly until August and the prisoners had been able to live as well as could be expected, but by the end of the year the deliveries were becoming increasingly scarce until none got through at all. The Russian prisoners had no Red Cross organization to support them and so the British shared with them what they could spare from their parcels. In the final few weeks of the year 1,800 US troops arrived at the camp in a far from fighting fit condition, and so a similar effort was mounted for them, this time with the permission of the camp Kommandant, but it was clear that what the British could spare would not be enough.

Forced march

As the Red Army continued its relentless advance through German occupied territory in the east, the Germans decided to evacuate the POW camps in the east and force march its occupants westwards, to no particular destination but away from the advancing Russians. A great many men from neighbouring Stalag 344 arrived at Görlitz, having endured appalling winter weather to join the Stalag VIII A prisoners on the march. The evacuation of Stalag VIII A began on 14 February when a large group of US soldiers with 140 British were marched off in the snow, followed the next day by a further 1,200. On the 17th a Hospital Train took 700-800 sick prisoners away to Stalag XI B at Fallingbostel, while the small number for whom room could not be found proceeded on foot or on the back of horse drawn carts. This procedure continued until the camp was empty and abandoned, however a few prisoners had hidden themselves in the camp to await the arrival of the Russians and their freedom.

For POWs whose diet had long been inadequate such exertion was an ordeal. It was made worse by atrocious weather during the winter of 1944–45. In the confusion of the march, food supply arrangements became haphazard. To add to the dangers, some of the POWs’ guards, resentful of the obvious decline in their country’s fortunes, took out their frustration on the men in their charge. Fortunately he avoided the fate of one New Zealander who was shot dead when he merely bent down to pick up bread thrown to him by compassionate civilians.

Some of these marches ended after many weeks when the groups arrived at large camps in central Germany, which were eventually overrun by Allied forces. Others continued marching until the end, when their guards generally disappeared and Allied units soon arrived.

After the German surrender the British, US and Russians forces liberated those POW camps still occupied, and of course the horror that was the Concentration Camps. Arrangements were made to repatriate Allied POWs (sick and injured first) as quickly as possible to their home countries. New Zealand POWs were sent first to the 2 NZEF repatriation centre set up by the New Zealand military forces in Kent, England. Pte. H-M’s family eventually received advice from Geneva (the Red Cross HQ) in April 1945 stating that Ron was “safe in the UK”. At some point during his incarceration, Pte. H-M would also have received a double blow to his morale – his older brother Ronald Charles Hay-Mackenzie had died in August 1943, and his father Albert Hay-Mackenzie had also died nine months before on 2 July 1944.

Rehabilitation in England

Pte. Hay-Mackenzie was evacuated to Alexandria, Egypt on the MV Oranje, a two year old Dutch passenger liner offered to the New Zealand and Australian governments as a hospital ship to transport casualties from the Middle East to England. Its refit as a hospital ship was completed in Sydney and commissioned as the 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship, MV Oranje in 1941.

On arrival in Alexandria Pte. H-M was admitted to No 5 NZ General Hospital (5 NZGH) in Helwan, Egypt where his condition was assessed and treatment initiated to restore his health. Once in a fit state to travel, he was shipped to the NZ Repatriation Centre in England. In late 1944 the NZ repatriation unit in England had established a Repatriation Hospital in an existing facility in Haine, Kent to receive 2 NZEF prisoners-of-war. Ron was admitted here and his treatment continued until he was fit enough to be repatriated to NZ.

Ron’s condition was such that he would have to remain in the UK for another six months before he could be repatriated to NZ. Life in the camps over the four years he had been interned (and on the six week march) had taken its toll on him. His ailments included Hyper-anxiety (Nervy, jumpy in public), Dysentery, recurrent Malaria, and Angioneuroti Oedema (a genetic form of Angioedema also referred to as Quinke’s disease). Persons with it are born lacking an inhibitor protein (called C1 esterase inhibitor) that normally prevents activation of a cascade of proteins leading to the swelling of the lower layer of skin and tissue just under the skin or mucous membranes. Swelling can occur in the face, tongue, larynx, abdomen, or arms and legs. Often it is associated with hives, which are swelling within the upper skin. Sufferers can develop recurrent attacks of the swollen tissues, pain in the abdomen, and swelling of the voice box (larynx) which can compromise breathing. Ron was also suffering from Chronic Blepharitis (characterised by chronic inflammation of the eyelids, usually at the base of the eyelashes. Symptoms include inflammation, irritation, itchiness, a burning sensation, excessive tearing, crusting and sticking of the eyelids). This condition was aggravated by the privations of POW life (poor sanitation, lack of access to clean water and a healthy diet, together with the prevalence of disease and infestations within the camp). If that wasn’t enough to contend with, Pte. H-M still required work on his teeth that had been previously smashed in Salonika. His nose remained as it had set.

Whilst in England, fortune favoured Ron in the form of a friendly face from home – his elder sister Catherine. Six years his senior, 38599 Private Catherine Margaret Hay-Mackenzie – NZWAAC had qualified as a civilian nurse in 1939. She had enlisted as a Staff Nurse in the Medical Division of the NZ Womens’ Auxiliary Army Corps (NZWAAC) on 18 Nov 1940, for the duration of the war. Over 500 members of the NZWAAC worked with, but were not members of, the 680 nurses and masseuses/physiotherapists of the NZ Army Nursing Service (NZANS) who served during WW2, both in NZ and overseas (these two groups were eventually integrated as the NZ Army Nursing Service in 1947). Catherine served in a variety of the NZ military hospitals and at the Repatriation Hospital. No doubt Catherine assisted her brother’s recovery, even just by being there. Catherine Margaret DICKSON returned to Westport after the war, married, and died in Westport on January 8, 2001 at the age of 95.

Homeward bound

Pte. H-M’s return to NZ started with his demobilisation on 10 Aug 1945, and travel home on 24 Sep 1945, bound for Auckland and all ports south. Pte. Ron Hay-Mackenzie disembarked at Lyttelton on 23 Oct 1945.

Not yet discharged from 2 NZEF, Ron had to undergo yet another Medical Board at the end of Oct 1945 at the Westport Hospital. In the interim however, he had gone to Auckland for some particular reason which ultimately resulted in a raft of correspondence making new appointments which were obviously not being communicated to him.

Seven months of medical clearance appointments booked, cancelled and re-booked, plus a requirement to expire his post embarkation leave before discharge, meant Ron’s final discharged from 2 NZEF didn’t come until 16 May 1946; Ron was then 33 years of age.

Medals: 1939/45 Star, Africa Star, British War Medal 1939/45, NZ War Service Medal.

Overseas service: 4 years 201 days

Total 2 NZEF service: 5 Years 130 days

After the war …

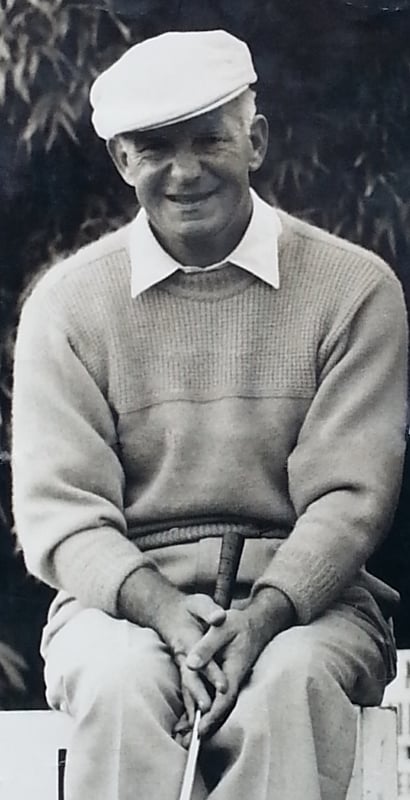

The return to a routine was a slow process for Ron as it was for most former POWs. He was a changed man. Jane, one of his daughters, was astounded to hear him described by a childhood friend years later as “the witty and handsome life and soul of the party.” What did keep Ron happy and sane after his wartime experiences were his supportive family and his love of golf. He was on the course as often as he could arrange it. Ron was a brilliant scratch golfer and, in another age, could easily have become a professional.

In 1946, Ron went back to full time work in Auckland but not for the bank but as General Manager of F. T. Wimble and Co, an Australian based company of ink manufacturers and printers. This was an ideal job for the still witty and personable sportsman as it gave him the opportunity to travel frequently to Australia, his trips often planned around the time of the Melbourne Cup.

Ron met his future wife Janet Hay (her mother’s maiden name) DRYSDALE (1919) on the Titirangi Golf Course in New Lynn. Janet was daughter of Charles Herbert and Louise Germaine Drysdale. She grew up in the Auckland suburb of Herne Bay, the second youngest of five siblings, they being Louise Boyd, George, Mary Forster and Peter, her beloved younger brother who died at the age of eighteen while training for the war on an Auckland beach.

Ron and Janet married in 1950 and bought a large rambling house surrounded by garden and fruit trees, opposite the Titirangi Golf Course, where they lived happily for the next twelve years. Their family of five children were – twins, Peter Ronald and John Alexander (1951), Robert (1955-1980), Jane Mary (1958) and Ann (1961).

In 1964 Ron decided to move the family to Taihape on state Highway 1, south of Waiouru Military Camp. There he and Janet became the licensees of the iconic Gretna Hotel. They enjoyed many friendships and the good times to be had in a friendly, small rural town. It was during this time that Ron suffered the first of a series of strokes that would slowly undermine his strength. After leaving the Gretna, he worked for a time at the only other hotel in town, the New Taihape Hotel, before he and Janet retired to Te Aroha near Hamilton in 1969. Janet became Ron’s full-time carer over the last ten years of his life as the first symptoms of Parkinson’s disease kept him housebound. One of Janet’s main tasks was to keep up a steady supply of library books for Ron’s voracious reading.

Ron, to his children’s regret and like so many of his generation, never spoke of his war experiences and as a consequence never had any interest in claiming the war medals that he had earned. It is only now, after his daughter Jane applied for his war medals, the family is learning of their father’s history during the Second World War.

16586 L/Cpl. Ronald Gordon Hay-Mackenzie – 23 Battalion, 2 NZEF – banker, soldier, prisoner-of-war, business manager, publican, husband, father and dedicated amateur golfer died at the age of 71 on 28 Feb 1979. Ron was interred in the Te Aroha Cemetery with his son Robert, whose death on his motorcycle happened the following year. Ron’s wife Janet, who had again successfully taken up her beloved golf in later years, moved to Rotorua to be within an easy drive of the golf course; Janet survived her husband by more than thirty years. She died, aged 96 on March 18, 2015 and is buried overlooking Lake Ngongotaha where she had spent idyllic family days in her childhood.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This story came about as a result of an approach made to MRNZ by a friend of Jane’s whom we had successfully assisted in recovering her father’s war medals. As a result, Jane contacted me in the belief that her own father’s WW2 medals might not have been claimed since her father was so reticent to speak of the war or be associated with anything that reminded him of his experiences as a POW. No family member could recall ever having seen and medals for Ron’s war service.

After researching the situation with the help of Karley (SME-R&E) at the Defence Force’s Personnel Archives & Medals section, I was able to advise Jane her father’s medals had never been issued. For Jane, being a surviving family member and one who is the immediate next of kin of her father, we were able to arrange for her to make a claim for her father’s medals.

Jane has now received her father’s medals and is now looking forward to ANZAC Day 2019 when she will be able to honour his Second World War service, recalling the years of incarceration as a Prisoner of War in Italy and Germany, by proudly wearing his campaign medals.

The reunited medal tally is now 250.

In 1976 this memorial was erected on the site of the former commandant’s office by French and Polish veterans who had been POWs. The sandstone plaque beside the memorial reads: Stalag VIIIA: A place sanctified by the blood and martyrdom of the prisoners of war of the anti-Hitler coalition during the Second World War – 22.VII.1976

In 1994 French veterans of the camp arranged for the black marble slab to be attached to the memorial which says in Polish and French: “1939 Stalag VIIIA 1945: Through this camp walked, in it lived and suffered ten thousands of prisoners of war”

Note: A total of 47,328, the highest number of prisoners in Stalag VIII A was registered in September 1944. Numerically, Frenchmen were in the majority, followed by the Russians, Italians, Belgians, Britons and the Yugoslavs. Finally in late December 1944 1,800 American POWs arrived, captured in the Battle of the Bulge.

~ LEST WE FORGET ~