4802044 ~ QUENTIN MORRISON COWAN, aka TIMOTHY CALLAN – Royal Lincolnshire Regiment

‘You wouldn’t read about it’ as the old saying goes when something you hear sounds quite unbelievable. Such was my reaction as I read and slowly pieced together the life of the Cowan family of Edinburgh, Scotland after receiving an email from Barbara H. of Hobsonville, Auckland. Barbara’s story relates to her deceased mother Agnes Glassey (nee Cowan) who came to New Zealand from Scotland in the 1920s, and the treasured memories she left behind when she died.

Treasured memories

Being mindful of her mother’s attachment to the keepsakes, and as they held no particular significance for Barbara or her sister, Barbara believed there might be family or someone closer to Quentin in the United Kingdom who would possibly appreciate having them. The problem was that because Agnes had very rarely spoken of her upbringing in Scotland, Barbara had no idea who Agnes and Quentin’s family were, where they might be found or even if any were still alive? Tentative inquiries made by her to UK Armed Forces, the NZ Defence Force and the Auckland Museum had been of little help. Unfortunately all Barbara really knew of her mother’s up-bringing in Scotland was, in a nut shell, that she had been born in Edinburgh in 1913, that her father’s name was GEORGE BLACK COWAN, that she had brothers and sisters both older and younger, and that her mother Mary Anne Cowan had died in the 1920s shortly after Agnes’s brother Quentin was born.

It was not much for me to go on from this distance but a case I was very happy to do whatever I could to either find a descendant, or an appropriate museum for the medals to go to if no family was apparent. I soon discovered this to be much more than a story about reuniting medals. There are many ‘unknowns’ and where these occurred I have declared them so. In order to get to the point of selecting a home for the medals to go to, I necessarily had to delve into the background of the families involved (extracted predominantly from the public records) before I could reach the foreground and an educated conclusion. The underlying story of a sister and her younger brother when viewed even from this distance was truly heart rending. Agnes and Quentin Cowan’s life was as incredulous as it was sad, but it allows us a glimpse of the way things were and the fate of the thousands of families like the Cowans, confronted by similar circumstances in pre and post World War 1 Scotland.

Where to start ?

Not much to go on but a case I was happy to take and do what I could to find either an owner or museum for the medals if no family was apparent. I soon discovered there was much more to this case than just finding a descendant. In order to get to the answers I needed, it became necessary to appreciate the circumstances of the families involved in their totality, and consequently revealed much more that need to be considered before determining the destination of the medals and memorabilia. Besides being a lengthy search for a fractured family, it was the underlying story of a sister and her younger brother that was truly heart rending. Agnes and Quentin Cowan’s story is as incredulous as it is sad, but also one that needs to be told if for no other reason than to reflect the way things were for thousands of families in pre-First World War Scotland.

As I perused the letters and cards it became very apparent to me that Agnes Glassey must have harboured a great sense of loss during her life in New Zealand, not because of anything she particularly experienced here – her life in many ways could not have been better – but because of an unrequited grief at the loss of a brother whom she had no chance to see before his untimely death. The reason was relatively simple – Agnes had no idea until much later in her life what had happened to her brother Quentin, how he made his way in life, or even what name he went by? Had there been letters or cards from him addressed to Agnes, it would have been logical to expect that some of these would have been found among her treasures but no, not a skerrick!

Aside from the three medals, Agnes’s mementos of her brother were unspectacular – a number of black & white photographs, some military papers, and a bundle of used postcards from Egypt, Ireland, Rome, Malaya, Singapore and Cyprus. A few others were from coastal tourist spots around England. The majority of these were addressed to a “Miss A. A. Bitten, 15 Orlando Road, Carlton, Nottingham.” As for the medals, the Defence Medal and War Medal 1939/45 (both un-named) were awarded for World War 2 service, and a third medal, the General Service Medal 1918-1962 had a clasp on the ribbon that read “MALAYA.” Around the edge of the medal was impressed the recipient’s name: 4802044. SGT. T. CALLAN. R.LINCS. REGT.

There was one other piece of paper that gave the starting point for researching this case. It was a rough photocopy of a Death Certificate in the name of QUENTIN TIMOTHY CALLAN, a Ministry of Defence Clerical Officer who had died at 159 Musters Road, West Bridgeford, Nottingham in 1973. The certificate had been completed and signed by Michael Ian Mills of 74 Conway Road, Carlton, Nottingham. Although the deceased was allegedly Agnes Glassey’s brother, I was still a long way from proving that so since Agnes’s maiden name had been CHRISTIE and then COWAN?

What follows is a summary of an almost six month search for answers to unravel this story in order to find a descendant primarily to return the medals to. The majority of these were from unsubstantiated Facebook and Ancestry contacts together with input from Wendy Haywood of Nottingham, and the little Barbara could recall from the scant mentions of her mother’s life in Scotland. I have attempted to develop this story in a logical sequence however some recap has been necessary to keep the people and events in some sort of chronological order. To better understand how Quentin Cowan came to be in the circumstances that became his life, I have attempted to outline his family background prior to his birth as it had a significant bearing on both Quentin and his sister Agnes’s future.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Digging up the past … the search begins

Agne’s mother – Mary Anne DOIG / CHRISTIE

Mary Anne DOIG (1866-1922) was the fifth of eight children born to farming parents Patrick Couttie DOIG (1833-1890) and Jean LOW (1842-1903). The Doig’s lived in Jean’s birth village of Kerrimuir, Alyth in Perthshire, an idyllic Scottish country village some 100 kilometres to the north of Edinburgh across the Forth Rive, near the port city of Dundee. In 1887, Mary Anne (20) who worked as a Jute Weaver in a Dundee sack making factory, married a Dundee Baker named Adam CHRISTIE (1866-1947) at St Mary Dundee. Adam Christie, also 20, and Mary Anne had two sons – William (1888) and Alexander (1889), named after Adam’s father. Their third child born in Sept 1891 was a daughter Jane. The Christies moved into a large stone accommodation block at 12 Sessions Street in Dundee’s city centre. For some unknown reason that printed records do not reveal to the reader, on May 6th, 1893 Adam Christie (24) boarded the cargo ship Croma at Dundee (only one of five passengers) and went to New York, never to return to Scotland again. Mary Anne could do little else with three children but carry on, with assistance from her siblings after her parents died.

Agne’s Father – George Black COWAN

William COWAN (1813, Innerwick), a ploughman and agricultural labourer, and wife Isabella (1816, nee BLACK, North Berwick) were both from farming families who had lived in the East Lothian counties of Haddingtonshire and North Berwick for generations. East Lothian is a rural farming district situated about 30 kms east of Edinburgh City. By 1871, the Cowans then in their mid-50s, moved with the rest of their family into the port district town of Leith, 30 kilometres away, to live with eldest son Peter Cowan (25 – b1845) and wife Elizabeth (27) at 43 Whitefield Place. Peter was a Gardener while his father William got work as a Warehouseman. In addition to Peter, Elizabeth and Peter’s parents, there were five other family members living at home, namely Christina (22 – b1848), Mary (18 – b1852), Jemima (16 – b1856) whose twin sister Agness was away temporarily working as a domestic servant for a local businessman, and last was Christopher Cowan (12 – b1860). Around 1876, Jemima Cowan had become pregnant and with no husband or financial support, was forced to become an inmate of the South Leith Poor House. It was here that George Black Cowan was born in 1877. Within eighteen months George’s 21 year old as yet unwed mother Jemima, was again with child. William and Isabella together with daughters Mary and Agness, took grandson George with them and left Leith for Coltbridge where William had taken a position as a Dairyman. Jemima Cowan gave birth to George’s sister who she named Jemima Black Cowan, in the last quarter of 1879. The “Black” in both George and his sister’s names was taken from their grandmother’s maiden name.

My efforts to identify George’s father were inconclusive. “Christopher” was not a particularly prolific name at the time and so the information I drew from was mainly associated with George’s year of birth, those named in Electoral Rolls in the Leith area (which necessarily includes Edinburgh as it is only 6.5 kilometres from Leith), and the fact that George had cited his father’s name in his Army enlistment documents as “Christopher Cowan.” I could find only three persons who potentially fitted the criteria which hinged around George’s birth year: a Sacking Manufacturer from West Bow in Edinburgh (age unknown), the 56 year old brother of George’s grandfather William, a farmer in an adjacent village to Innerwick, and Jemima’s younger brother Christopher, four years her junior. These led me nowhere in particular short of suggesting impropriety.

My only comment which may or may not have any bearing, possibly ruling out one of the Christophers, relates to Jemima’a brother. Christopher Cowan was a 17 year old a Baker in Leith when George was born. Living at home, he and sister Agness were the only two siblings consistently living at home with their parents. Their siblings lived and worked with their employers for varying periods of time. As George was still a baby when he came to live at his grandparents place, it likely fell to Agness and Christopher to look after George, in the manner of parents. It is not much of a stretch to understand why George quite naturally could have believed Christopher to be his father, until told otherwise when much older. As things transpired he probably never was. Shortly after 1881 when George was four, Christopher Cowan (19) left East Lothian and went to England, to Woolwich where he enlisted for the Royal Artillery. Clearly he made it a career as he is listed in an 1891 English census as a soldier with the rank of Bombardier (equivalent to Corporal) living at Portsea Island, Hampshire. By 1901 he was out of the army and listed as a Time Keeper in the south-east London suburb of Bermondsey together with his wife, Rosa Hannah CLARKE (married in 1890, no children in evidence). As far as is I could determine the couple never returned to Scotland.

Another twist to George Cowan’s parentage that had me thinking was an entry in the 1891 Scottish census which listed George’s mother as Agness Cowan, Jemima’s twin sister. Given the comment above about George being cared for by Agness in his mother’s absence (in the South Leith Poor House), George who was 14 at this time had probably spent more time with Agness than his mother. Perhaps he was not yet aware of who his real mother was? That this entry was incorrect was proven with George’s First World War enlistment papers. In these he records all members of his family which at that time (1914) included his mother’s then married name, Jemima MORRISON and his sister Jemima Black (Cowan) Morrison, and six other half-brothers born to his mother and husband Robert MORRISON who George had annotated “step-father” against his name.

George Cowan’s working life had started as a Messenger Boy in Leith in 1891 when he was 14 years old. His grandparents, then in their 70s, had moved from Coltbridge to Edinburgh City where William became a Society Collector (street collector of donations for various societies, e. g. the Blind etc). At 16 George was working as a Cellarman and at 17 he had a labouring job in a grain (flour) mill. This led to his acquiring the skills of bread making and those of a tradesman Baker. He had been baking in Leith for about three years when the prospect of something potentially more exciting and better paid enticed him in a new direction. George was 21 when he took his first steps towards a career in the Army – he enlisted in the Militia Reserve at Leith, the 3rd Battalion, 1st (Leith) Midlothian Rifle Volunteer Corps, 1st Foot Regiment (Royal Scots) on 12 December 1898.

The Royal Regiment

7496 Private George Black Cowan had indeed joined an esteemed regiment with a huge history. Formerly known as the Royal Regiment of Foot, the Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment) was the oldest and most senior infantry regiment of the line in the British Army having been raised in 1633 during the reign of Charles I of Scotland.

In 1898 comprised three battalions – the 1st and 2nd Battalions (Royal Scots) were manned with regular army infantry soldiers while the 3rd (Queen’s Edinburgh Light Infantry Militia) Battalion, being a Reserve Battalion was primarily staffed with militia soldiers (part-timers). The 3rd Bn was based at Glencorsey, about 11 kms south of Edinburgh and so very handy for George.

At the time George enlisted, the 3rd Battalion (or 3rd Royal Scots as it was known) was preparing to to go to South Africa with the 1st Battalion. The 2nd Battalion had been extensively involved in the Second Opium War in China some years before so on this occasion the 3rd Bn was selected to support the 1st Battalion, the Regiments primary regular fighting unit. Most of their time would be spent on mobile column work, patrolling and raiding expeditions.

South Africa

The discovery of gold and diamonds in the British Empire’s colony of South Africa was the trigger for escalating years of unrest by the Boers of the two independent states of Transvaal and the Orange Free State, to a state of war. The Boers would attempt to eject the Empire from South Africa once and for all. British troop numbers were increased in preparation for what looked like an escalation to a state of war. Word travelled throughout the military communities world-wide and likely became a motivating factor for 21 year old George Black Cowan to hasten his decision to enlist.

The Anglo-Boer War or South African War, also known as the Boer War, Second Boer War, or to Afrikaners (Boers), the Second War of Independence was fought from 11 October 1899 to 31 May 1902 between Great Britain and the two Boer (Afrikaner) republics – the South African Republic (Transvaal) and the Orange Free State. The rising political independence of the Afrikaners in these two states threatened British interests and their peoples in this former British protectorate. In addition, the Witwatersrand gold-mining complex located in the South African Republic (SAR) was also seen to be a key factor that could be used as leverage to eject British influence and interest from the country. While the Witwatersrand mine was not owned by Britain, numerous Britons and other foreigners worked there. It was the largest gold-mining complex in the world at a time when the world’s monetary systems, pre-eminently the British, were increasingly dependent upon gold. It was also seen to be the key to the rapid modernisation of the SAR which would work against British interests. Britain considered the escalating situation was at a stage that warranted military intervention and so initiated a strengthening of troop numbers along the country’s borders.

The Boers, realising war was unavoidable, had taken the offensive. On October 9, 1899 the SAR issued an ultimatum to British government, declaring that a state of war would exist between Britain and the two Boer republics if the British did not remove their troops from the border. The ultimatum expired without resolution – the war began on October 11, 1899.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Private Cowan was offered a “Short Service” contract, that is – 3 years with the Colours and 9 years in the Reserve. Signed at Woolwich, he was committed to the Army for the next 12 years. At any time in those 12 years George could be mobilised in the event of war or a national emergency. He was assigned a new regimental number, T/14306 and the rank of Driver.** He was Attested at the Woolwich Barracks in London in January 1899, and then spent the next 10 months learning how to set up, operate and take down field kitchens. In particular he specialised in the operations of the Field Bakery. Producing hundreds of loaves of bread every day was one of the primary functions of the wood-fired ovens of the Field Bakery.

Dvr. Cowan embarked on the SS Tintagel Castle on 17 December 1899 with the 1st Company, Army Service Corps bound for the port of Durban, South Africa.

Note: ** All soldiers in the ASC/RASC were ranked on entry as “Drivers”, the equivalent of a Private in the Infantry. “Driver” is a generic term for all trades-persons whether a horse or motor vehicle driver, cook, storeman, medic, mechanic etc.

During the one year and 106 days Dvr. Cowan served in South Africa, he was attached variously to the 10th and 24th ASC Companies to support the 63rd Howitzer Battery, Royal Field Artillery (RFA). On 2 April 1901, Dvr. Cowan (23) returned to Edinburgh. By the time his leave had been expended for service to date, his three years of regular service were completed, and as the “Short Service” law required, men were to be returned to England and discharged or re-contracted after a period of leave.

The 3rd Battalion (Royal Scots) embarked at Cape Town on 7 May 1902, shortly before a treaty to end the war was mutually negotiated. The Peace of Vereeniging was signed in Pretoria on 31 May 1902. The battalion was disbanded on 28 May 1902, having lost 4 officers and 31 other ranks killed or died of wounds or accidents. On returning to England, Dvr. Cowan was discharge from Active Service and returned to the Militia Reserve on 30 Sep 1902.

For his service in South Africa, Dvr. Cowan and all participants were awarded the Queen’s South Africa (QSA) medal with clasps: CAPE COLONY, ORANGE FREE STATE, TRANSVAAL and the King’s South Africa (KSA) medal with two clasps: SOUTH AFRICA 1901 and SOUTH AFRICA 1902.

Special Reserve (SR)

After the war, a re-organisation and reassessment of the role of the Militia resulted in a semi-professional force whose role it was to provide reinforcement drafts for the regular units serving overseas in wartime. The battalion was re-named the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, Royal Scots on 9 August, 1908.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

COWAN & CHRISTIE

This is the point at which the COWAN and CHRISTIE names converged but exactly how and when is still up for debate. George Cowan returned to Edinburgh and eventually went back to work as a Baker in Dundee. Whether or not George had had anything to do with the Baker Adam Christie (ten years George’s senior) either as tradesmen or privately, is unknown, however given Adam had been gone since 1893 it would not have been unusual for Mary Anne Christie in her circumstances with three children, to take in a Lodger for the added financial support. Whether George Cowan was a Lodger at 12 Sessions Street where Mary Anne Christie had remained after her husband left, or whether George and Mary Anne met socially, again is not known. What is clear however is that at some point after George returned from the Boer War, he and Mary Anne Christie who was eleven years his senior, became more than acquaintances.

An unexpected arrival

As was prone to occur with such relationships, Mary soon became pregnant making hers and George’s positions in Dundee untenable. Mary (38) left her three children in the care of her eldest, William then 19 together with brother Alexander 18, and sister Jane Christie 15, and went to Edinburgh with George (29). They rented a small place in a three story accommodation house at 33 Buccleuch Street, Newington in South Edinburgh. On 21 November 1906, Mary gave birth to hers and George’s illegitimate daughter, Margaret Ann CHRISTIE. There was no discussion of marriage and in due course Mary was able to go back to work, employed as a Sack Machinist (sewing hessian sacks) perhaps for sack manufacturers William Bell and Christopher Cowan of 87 West Bow? I discovered an interesting coincidence in that William Bell thirty years prior had lived in the same street, Whitfield Place in Leith where the Cowan’s had lived after leaving East Lothian.

George in the mean time worked as a labourer while still doing Army Reserve training when possible. It was apparent to Mary that George had not expected nor particularly wanted the responsibility of children and had showed little interest in fatherhood during baby Margaret’s first years of life. This was hardly surprising recalling George’s own start to life. Children were a liability that required money. Whether or not he had made any financial arrangements to support his daughter (as was required by law for children born out of wedlock) is not known but George stuck with the relationship while he figured the best way out of his predicament was to try for a permanent contract with the Army for full-time service.

George Cowan had remained with the renamed Special Reserve’s 3rd Battalion, Royal Scots since returning from South Africa however, his 9 year Reserve commitment was due to expire in September 1910. He hoped his active service in South Africa and continued Special Reserve service would be looked upon favourably in an application to extend his service. George (30) applied for a four year extension with the Royal Scots in January 1907 (without Mary’s knowledge) which would take some months before he had an answer. When Mary learned he was renewing his army service, she was less than impressed and left Edinburgh with four year old Margaret Christie (George would not have his Cowan name associated with her) and returned to Dundee. Mary moved got lodgings at 32 Lawson Place and soon returned to factory work as a Jute Winder (winding jute fibre onto spools for export or use in weaving) daughter Jane looked after Margaret.

‘Hell hath no fury ..’

Driver Cowan was released from prison on 26 Dec 1910 and returned to his mother’s home but unbeknown to George, she had left Paisley to live in Leith (where George was born). Jemima Cowan had re-married. Her husband Robert MORRISON (1852-1947) came from Coatbridge, an Iron Moulder who usually lived in Glasgow. Jemima and Robert were temporarily living at 170 Morrison Street in Leith until Robert’s Glasgow residence at 27 Darnley Road, Barrhead became available. So, most unexpectedly George Cowan met his new step-father and an additional six Morrison step-brothers! – Quentin (25) a Lorry Driver (formerly a Lorry Nipper**), Robert (21) an Iron Moulder, Andrew (19) also an Iron Moulder, plus Christopher (a scholar) and two pre-school aged infants, John and James. Plus of course his sister Jemima Black (Cowan) was there – she had altered her surname to Morrison. George was put up by family friends in Leith until he could return to the Army in the new year.

Note: ** A ‘Lorry Nipper’ was a young teen who assisted a carter or carrier to load and unload the cart or truck/lorry.

Return to the Royal Scots

In the first week of January 1911, Driver George Cowan, RASC reported for duty once again as previously directed, and signed the dotted line on his renewed contract without hesitation. He had a four year engagement with the recently re-named Royal Army Service Corps but … not with the Regular Army? To get that he was told he would have to prove he warranted a full-time contract by first sorting out his personal situation, otherwise he would be considered a liability to the Army. Until this was done explained his CO, he would remain in the 3rd Battalion (Reserve). During the next six months or so, George reconciled to live with Mary Anne and daughter Margaret in Dundee. The renewal of their relationship also heralded the arrival of a second daughter Agnes, later in the year on 21 September 1913. Having stabilised his and Mary Anne’s residential arrangements George accepted responsibility for the Christie named children by giving them his surname. Agnes registered birth name (Agnes COWAN) was correct so no change was needed, but her older sister born Margaret Ann CHRISTIE ceased to exist (in name only) and henceforth was known as Mary Anne (after her mother) Christie COWAN, “Annie”as she was generally known. It is believed Annie’s assumed name was never lawfully altered.

Mobilisation – 1914

Tension had gripped the nation as the daily newspapers carried reports of the escalating political instability in Europe that threatened Britain and her allies. Britain had already begun to mobilised the Armed Forces. The assassination of Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to Austro-Hungarian Empire, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, was the spark that set the war alight. The assassin was a supporter of the Kingdom of Serbia, and within a month, Austria had declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914. Once Germany declared war on Russia on 01 August, it became inevitable Britain would be drawn into the First World War.

At the outbreak of war The Royal Scots consisted of two Regular battalions, the 1st, at, or close to full strength of some 1000 all ranks, in India, and the 2nd, needing reinforcement by some 500 Reservists, at Plymouth. On the eve of World War I, the Royal Scots consisted of 10 battalions, with eight more based in the Lothians. T/14306 Dvr. George B. Cowan and the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion was based at Glencorse along with the regimental depot and seven other Territorial Force (volunteer reserve) battalions which had drill halls spread across the region. The 3rd (Reserve) Battalion went to its war station at Weymouth in Dorset. As well as its coastal defence duties, the battalion’s role was to train and form drafts of reservists, recruits and returning wounded for the regular battalions of the Royal Scots. The Royal Scots ultimately would become one of the most decorated regiments of the First World War, with an estimated 100,000 soldiers serving in the regiment over the duration of the conflict.

7th Division, BEF

The 7th Infantry Division, a mothballed Regular Army formation, was re-activated in Sep 1914 and manned by combining units returning from garrison outposts in the Empire such as India, China and Malta with almost 50% of its strength being made up from Reservists. Unlike the first six regular divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), a third of whose strength was made up of regular Reservists, the 7th Division was originally composed entirely of serving regular soldiers which had given rise to the Division’s nickname ‘The Immortal Seventh’. To bring the Division up to strength, the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion would be required to deploy overseas.

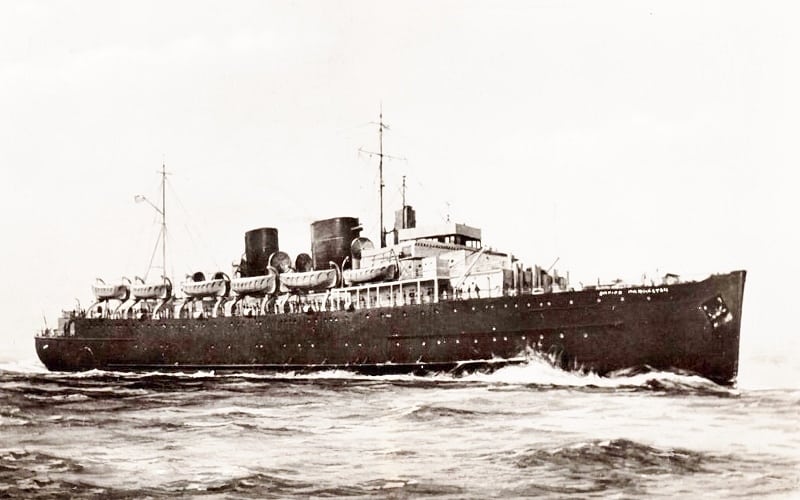

Dvr. Cowan embarked on the SS Armenia on 5 October 1914 as a member of No.2 Company in 1/8 Battalion, 22 Brigade (of the 7th Division) which landed at Zebbrugge, Belgium the following day, 6 October 1914 to support the Belgian Army’s defence of Antwerp. Resistance was severe and it was soon forced to retreat south-west as that city fell a few days later. The 7th Div then played a crucial part in the stabilisation of the front during the First Battle of Ypres in Western Flanders from 19 Oct – 22 Nov 1914. The BEF successfully prevented a German breakthrough but at great personal cost to the 7th Division.

Dvr. Cowan was in France for most of 1915 having participated in the battles of Neuve Chappelle, Aubers Ridge and Festerbut. On 16 Jan 1916 he was withdrawn from the field with “Debility” and returned to Edinburgh having spent 1 year and 105 days at the front. His withdrawal also coincided with the completion of his 12 year “Short Service” engagement. Men who reached this point were automatically withdrawn from the field upon the expiration of their “Short Service” contract (for legal reasons) and discharge “services no longer required”, pending re-engagement, or termination of service at the soldier’s request. George Cowan, then 38, was discharged from the BEF on 29 June 1916 after a total of 17 years of territorial and regular service, 5 years Active Reserve and 12 years Regular Army service, however he had every intention of re-engaging for service in the Special Reserve.

For his service in Belgium and France, Dvr. Cowan was awarded the 1914 (Mons) Star, British War Medal 1914-18, Victory Medal and the Silver War Badge (SWB). The SWB was issued in the UK and British Empire to service personnel who had been honourably discharged due to wounds or sickness from military service. The badge, sometimes known as the “Discharge Badge”, “Wound Badge” or “Services Rendered Badge”was first issued in September 1916 along with an official certificate of entitlement.

Note: The Royal Scots were awarded a total of 71 battle honours and 6 Victoria Crosses. Of the 100,000 men who served in the Regiment over the course of the war, 11,162 were killed and 40,000 wounded.

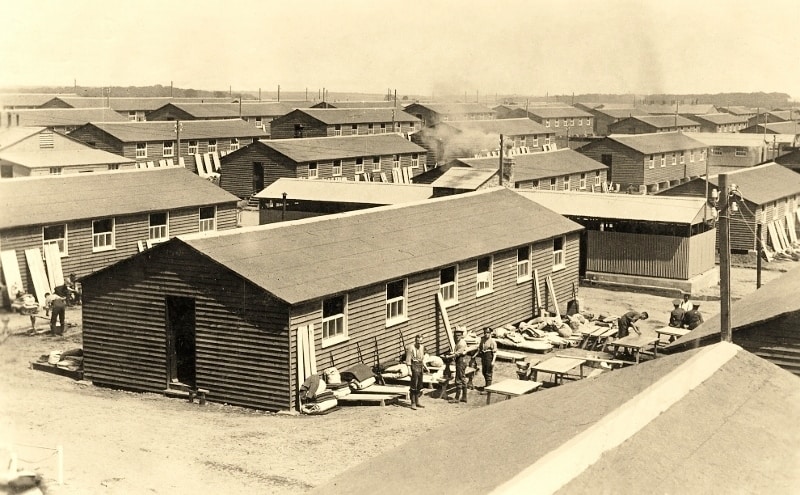

Back in Edinburgh, Dvr. Cowan returned to the Reserve. Shortly thereafter he was promoted to Corporal and appointed an as instructor at the RASC’s Field Bakery Unit at Clipstone Camp in Mansfield, North Nottinghamshire (Notts).

The Notts Evening Post, 10 July 1914

– ‘The Khaki stream continues to flow to Clipstone’.

Several more battalions have arrived during the week. On Wednesday over 1,000 men of the ASC [Army Service Corps] came along and have gone under canvas. Some of them are quartered close to Sherwood Hall, others have passed to the new camp at Rufford and the remainder have a triangular piece of land at the entrance to the Dukes Drive at Clipstone’. With upwards of 30,000 soldiers at Clipstone Camp at any one time, soldiers both in training and on the march were a regular sight for miles around.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Marriage and …?

Whilst George Cowan was overseas, Mary Christie had given birth on 3 Feb 1915 to their first son (and third child), George Christie COWAN. On the March 5th, 1917 George (41) finally formalised his and Mary’s (34) status as a legally wedded couple. They were married at St Mary’s Dundee Parish Church in the presence of Mary’s mother, Margaret DOIG (nee Adams). Mary’s father William Doig had deceased. The Cowan’s continued to live at 23 Albany Terrace in Dundee however predictably, the marriage was fraught with problems that were an extension of their pre-marital life together. These were no doubt exacerbated by George Cowan’s predilection for alcohol and spending time with his Army pals he had gone to South Africa with.

The Cowan’s fourth child and second son, Quentin Cowan,was born on 13 April 1920. By mid 1922, Mary Cowan’s health had taken an unexpected turn for the worst and declined rapidly – Mary was in serious trouble. The diagnoses was Intestinal Carcinoma which had given rise to a malignant obstruction, known as “MBO”, which in Mary’s case was an advanced form of gynaecological cancer. Within 90 days of the diagnosis, Mary Ann Cowan was dead at the age of 56. She died at Dundee on 12 November 1922 leaving husband George (44) to care for their four children – “Annie” (Mary Anne – 16), Agnes (9), George Christie (7) and 18 month old baby Quentin. A fifth child Christopher living with the Cowan’s at the time, is thought to have been Christopher Morrison, sister Jemima Black Morrison’s son and one of George’s nephews.

Death and division

After the death of his wife, George Cowan had neither the will nor the capability to look after his young family, and besides, he had already made plans to re-enlist. He wanted the freedom to continue his military service which would mean he would not have time for child care. While his eldest daughter Annie remained at home to keep house for her father, George made arrangements for Agnes and her brother George Jnr to be packed off to an Industrial School (orphanage). As for little Quentin, George had him taken into the care of an Industrial Home’s Maternity Wing. Without telling his children what he had planned, while they were out of the house George arranged for Quentin to be taken. Miss Agnes Bitten, the Matron in Charge arrived to collect little Quentin.

Privately financed establishments to house children of the poor and those whose families had encountered diminished circumstances, were prolific in England, Ireland and Scotland. In Edinburgh and Glasgow, industrial schools, Barnardo’s Homes, Working Lad’s homes and Reformatories had all grown from a dire need. High rates of illegitimate birth and financial hardship created by low wages and promiscuity was the lot of a large and predominantly poor population of industrial working class people crammed into sub-standard tenement housing that had been built in the 19th Century. Edinburgh and Glasgow were just two of many city centres that reflected this way of life

-

Templedean

It is not known which of the institutions George Christie Cowan finished up in however he and Agnes would reconnect in the years to come. Agnes went to one of three coincidentally named Christie Industrial Homes for Girls. Founded in Edinburgh city in 1899, “Tenterfield” was the first of several Christie Homes that were privately funded by a wealthy benefactor named John Christie (1822-1902) – no relation to the Christie family in this story as far as I am aware. Christie’s father, Alexander (1789-1859) who had been a colliery owner and iron-founder had amassed serious wealth during the 19th century and acquired large acreages of land in and around the city of Edinburgh. His son John had inherited his estate after his death in 1859 and during his lifetime, John added to the wealth and land accumulated by his father.

The first Christie Industrial Home for Girls was opened in the Edinburgh suburb of Portabello in 1892. “Tenterfield”, an orphanage in Haddington (and the home of George’s mother, Jemima Cowan’s family) was opened in 1898. “Templedean” was opened in 1903, and the adjoining establishment “Carmendean” in 1912. The Christie Homes were ostensibly for girls whose families had fallen on hard times. These orphanages were in the style of large manor houses with an average of six bedrooms that could accommodate 4-8 girls, depending upon their age, and from many anecdotal account available today, by and large the girls were well treated, fed and educated. Girls were accepted from birth until the age of 18 and received training for domestic service so they would have a job and a home when they left. The girls were also educated at one of the local primary schools which was not permitted to be more than half a mile from the Home.

Many former inmates have glowing memories of their time at these homes, and speak with affection for many of the staff who ran and managed the Christie Homes. John Christie had high standards in this regard and oversaw the treatment and management of the homes on a regular basis – it was his personal passion. In his senior years, John Christie became an increasingly eccentric and narrow minded philanthropist, his eccentricity being exacerbated by an incurable pernicious anaemia – an autoimmune condition induced by lack of Vitamin B-12 uptake and may require life-long treatment to control symptoms. Severe or long-lasting pernicious anemia can damage the heart, brain, and other organs in the body. John Christie died in 1902, aged 78. The morning after his death a stranger arrived at his townhouse at 19 Buckingham Terrace, Edinburgh and informed his carer daughter Ella Christie, that her father had executed a will that left all his property to his orphanages and she and her sister were to get nothing, much to their mortification. The will was contested in the years to come – a 50% settlement only in favour of Ella resulted.

Some family members of George’s Cowan’s mother Jemima were still living in Haddington in the 1920s and so it is highly likely that Agnes Cowan would have been placed at “Templedean”, also considered to be the best of the Christie Homes.

Agnes’s enrolment at Templedean had necessitated an unofficial modification to her name. Registered at birth as “Agnes Christie” after her mother’s surname as her father George Black Cowan and mother Mary Ann Christie were not married, the potential for problems if Agnes were enrolled as a Christie were fraught. By enrolling her as Agnes COWAN, her father could avoid embarrassing or searching questions regarding the apparent anomaly in the parentage of Agnes Christie and her biological brother George Christie Cowan?

Another reason for putting Agnes into Templedean was a family connection at the Home. Barbara recalled her mother once telling her that she remembered two maiden aunts from the Cowan family on the staff (George’s sisters?). She told Helen that both of the aunts lived on the top floor and that both had a hand in Agnes’s upbringing. She also recalled the aunts used to enforce a strict rule in the building – no whistling on Sundays!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Cowan children …

ANNIE’s story

According to Agnes Glassey, in 1928 her twenty three year old elder sister Annie Christie Cowan had apparently had a blazing row with her father which resulted in Annie storming out of the house saying she was leaving for good. Agnes had said Annie went down to the Leith docks with the idea of getting on a ship that was going to Canada. When she got to the port, there was no Canada-bound ships in but there was one going to New Zealand. With no money for a fare Annie intended to see if she could work her passage in the galley, cleaning cabins, or in the ship’s laundry. Whatever pitch she made to get aboard must have worked. Within days she had left Edinburgh, never to return.

-

Stability at last

Just where and how Annie Christie Cowan and Bill Matthews met remains a mystery but within months of Annie’s arrival in New Zealand, the two were married! Annie did however have an agenda which may have been the reason for haste. Annie had promised her teenage sister Agnes that she would get her out of Edinburgh and bring her to New Zealand as soon as she was able. Part of her plan necessitated she be settled and have a permanent home address as soon as possible. Since Agnes was still a minor (under 21 years), immigration law required that she be ‘sponsored’ by a fit and proper person of mature age, who could guarantee Agnes’s passage costs, that she would be looked after on arrival, and that a permanent residential address of her Sponsor in the destination country be provided.

Annie’s whirlwind marriage was to a Devonshire native, William “Bill” Matthews whose family home was at Lee Mill near Ivybridge. Born on 14 Jan 1892 at Plympton St Mary, Bill Matthews and his older brother Thomas (1888-1941) were the only two sons in a family of eight sisters born to parents James MATTHEWS (1846-1914) and Mary Ann BROCK (1853-1921). Bill was a 20 year old Blacksmith at the time he migrated to NZ in 1913, shortly after his father died the previous year. On arrival he made his way to Westland, working as a miner in the Blackball Coal Mine. Blackball, 30 kms north of Greymouth, had been named after the Blackball Shipping Line which leased land in the area to mine for coal. From Blackball, Bill Matthews went to Kaikoura and engaged in general labouring work. His brother Thomas (“Tom”) emigrated to NZ the following year in 1914 and linked up with Bill at Kaikoura. The Matthews brother’s two youngest spinster sisters, May and Althea had remained at home in Devon with their mother with the intention of emigrating to NZ once she had passed away – which she did in 1921. Althea (21) was the first to emigrate in Dec 1921 and settled in Christchurch. Her sister May, a year younger than Althea, arrived in Auckland around 1925 and went to Dargaville where brother Tom Matthews and his wife had started farming. May Matthews was 38 when she married at Dargaville in 1934 but unfortunately died suddenly the following year.

-

Marriage and the war

By February 1917, bachelor Tom Matthews had married Kaikoura born Leah McLeod. The couple left Kaikoura and went north to Whangarei to start farming, finally settling on a piece of leased land at Dargaville. Bill would love to have gone with them however he had been balloted for war service.

37689 Sapper William Brock Matthews, NZ Engineers was 23 years 9 months of age when he enlisted at Kaikoura on 15 March 1917. He proceeded to Trentham Camp and was placed with the 5th Tunnelling Reinforcements, NZ Engineers Tunnelling Company. Spr. Matthews embarked on HMNZT 84 Turakina at Wellington on 26 April 1917 bound for Suez and preparatory training for the Western Front. On arriving in France, Spr. Matthews’ was posted to the 2nd NZ Field Engineer Company for their induction training at the NZ Engineers training camp in Christchurch, Dorset. Together with a 100 or so others Kiwis soldiers, their first job on the Front saw them detached to the 3rd French Army to assist the French dig in their artillery battery emplacements and build protective bunds around them. The French artillery units were seriously undermanned with soldiers. They had neither the manpower nor the where-with-all for this task (no shortage of officers) and so required supplementary assistance before their guns could be effectively employed in the forthcoming Battle of Messines. Within months Bill had gone down with severe gastritis, being hospitalised initially at Rouen before returning to the NZ Stationary Hospital at the Etaples Base Depot. Back into the field several months later, Spr. Matthews was ‘wounded’ in Nov 1917 after being subjected to gas poisoning from enemy artillery gas shells. Fortunately his gassing was not severe enough to kill, but was enough to debilitated him considerably. Spr. Matthews was evacuated by hospital ship back to No.1 NZ General Hospital at Brockenhurst in England for treatment and to convalesce. Following his release from hospital, Bill was retained in England and posted to the NZEF Engineer Depot at Christchurch in Dorset until he was repatriated.

With the Armistice signed on 11 Nov 1918, Spr Matthews returned to NZ in Feb 1919 having spent 1 year and 337 days overseas. For his service he was awarded the British War Medal, 1914-18 and the Victory Medal. Sapper William Matthews was discharged from the NZEF in 1919, “no longer fit for war service on account of wounds received in action” on a day that is now legend in NZ’s military history, 25 April – Anzac Day. Bill’s discharge date was the 4th anniversary of the Gallipoli Landings.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bill Matthews returned to Kaikoura for a brief period before heading to Wellington were he picked up a contracting job, presumably blacksmithing. His address at that time was 19 Hutt Road which is now part of the Pipitea suburb, directly opposite the Aotea Quay rail yards. He stayed in Wellington for several years before going north to Dargaville to stay with his brother Tom and wife Leah.

Bill was still in the Dargaville at the time Annie (Mary Anne) Christie arrived in New Zealand on board whatever ship she had managed to get on. I can only assume Bill and Annie must have crossed paths either in the Kaipara/Whangarei area where there was a major port, or perhaps in Auckland or Wellington? Apart from his time on the West Coast, Bill had only spent time in these two other cities between 1919 and 1928 (according to Electoral Rolls). The point is that Mary Ann (23) and Bill (27) had met and irrespective of their personal motivations, were married in a matter of months in 1929. The Matthews went south to Canterbury where Bill leased some land to start a farm in Carters Road at Greenpark, about 5 kms south-west of Taitapu near Christchurch (the farm was possibly a returned serviceman’s rehabilitation allotment). Bill and Mary ran a mixed farm at Greenpark for the best part of 15 years. During this time they did not have any biological children, probably the reason they adopted a son they named William Graham Matthews, in Oct 1933.

The Matthews left their farm at Greenpark not long after the Second World War ended and moved into 71 Hay Street in the East Christchurch suburb of Linwood. Their original house remains to this day, still bearing evidence of the time the Matthews lived there in the form of a stone fence Bill had built along the front of the property. One further move for the Matthews family in 1950, a few doors down the street to number 74 was Bill, Mary and “Bill” Jnr’s last. Bill Matthews Snr died at home on 02 Oct 1953, aged 60 and was buried in the Sydenham Cemetery. Mary Anne Christie Matthews (nee Cowan) survived her husband by another 25 years at the same address before she too passed away in 1978 aged 72. Son Graham left Christchurch to live in Newlands, Wellington and married Mima May A., a school teacher. His occupation was listed simply as ‘Manager’. W. Graham Matthews died at Waikanae on 07 May 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

AGNES’s story

By 1929, Agnes Cowan had been out of Templedean Girls Industrial Home for almost a year and working in Edinburgh Old Town as a domestic servant. She lived in a rather grim looking accommodation block in New Assembly Close which, as the records seemed to indicate, was not a random choice. According to the 1928-1929 Electoral Roll, Agnes and Matron Aggie Bitten were both living at New Assembly Close. Matron Bitten was listed as living at No. 142a and Agnes at No. 142. Far from this being coincidental, it is believed Aggie Bitten had arranged for Agnes to be next door so she could keep a watchful eye on her while Agnes could care for, and spend time with her brother Quentin from whom she had been parted for almost seven years.

During her time at Templedean, Agnes’s elder sister Annie now settled in New Zealand had kept in touch with sister, being the architect of a plan to get Agnes to New Zealand. Agnes hated the thought of being separated from her little brother (now nine years old) but this was an opportunity she could ill-afford to pass up. She would be back and hopefully Quentin could also return to New Zealand with her? Little did Agnes realise that when she said goodbye to Quentin and Aggie Bitten, it would be the last time she would ever set eyes on them.

Agnes never having travelled before, Annie’s plan called for her sister to get to the London Docks, quite a considerable distance from Edinburgh. There would be a ship due to depart on December 2oth for Wellington – Agnes was to be on it! Annie had arranged a Third Class ticket – the cheapest available was £38 (value in 2020 = £2,429.96 or NZ$4999.00), and for Agnes to be chaperoned to London by some very helpful Dundee relatives who would help Agnes with her embarkation.

-

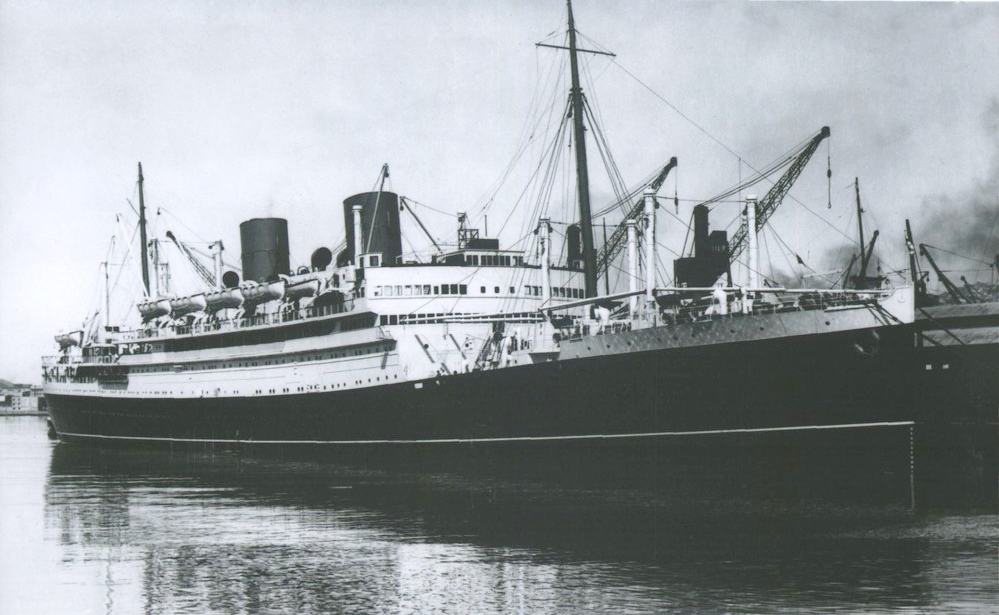

Escape !

On 19 December 1929, sixteen year old Agnes Cowan left Edinburgh with her chaperones, on the Edinburgh–London express to where the New Zealand Union Steam Ship Company’s RMS Rangitane was berthed in London. Unbeknown to Agnes she would be sailing aboard a brand new passenger liner, the last of a trio of liners built for the Union Company. The voyage to New Zealand would be Rangitane’s ‘maiden voyage’! Launched on 27 May 1929 at Clydebank near Glasgow, the Rangitane was finished in November and scheduled for departure on her maiden voyage from London to Wellington on 20 December, 1929. The ship was scheduled to check in at Southampton on the 21st, Madeira in Portugal on the 25th, then through the Panama Canal and across the Pacific to reach Auckland no later than 26 January 1930. The maiden voyage would take a week longer than normal sailings as the ship’s new power plant had to be gently ‘run in’ before it was allowed to run at maximum speed. This she would be able to do on the return voyage by which time the engine components would have eased sufficiently.

RMS Rangitane arrived at Auckland on schedule, five weeks after departing London. Agnes remained on board until eventually disembarking at Wellington when the ship berthed at the overseas passenger wharf. She then needed to find overnight accommodation as the ship’s inter-Island service to Lyttelton, Christchurch would be departing the following evening. This must have been quite daunting for a 16 year old travelling alone but Agnes managed it without difficulty. The following day Agnes spent a leisurely day wandering about Wellington and its sights before reporting for the ferry terminal in the late afternoon. The overnight inter-island ferry departed at 7 p.m. and was scheduled to arrive at Lyttelton around 9 a.m. in the morning. As her sister Annie Matthews had promised, Annie was waiting on the wharf as the ferry slowly made its way through the breakwater to the passenger terminal and berthed. A predictably tearful and joyous reunion ensued before Annie introduced her sister to her new brother-in-law and husband, Bill Matthews.

-

Making a home in ‘Godzone’

Mary Ann Matthews (no longer Annie) and husband Bill took Agnes to their Greenpark Farm that was located south-east of Taitapu. This Agnes would call home for the foreseeable future until she decided what she wanted to do – to stay or to go back to Edinburgh? After a year at Greenpark Agnes made the acquaintance of Mr George William GLASSEY (b1908), a Butcher from Springfield who with his father Charles Robert James GLASSEY (also a butcher) and mother Dorothy May Glassey, ran a butcher’s shop. A five year courtship between George and Agnes ensued before they decided were married in June 1934. The 21 year old Scottish lass was filled with hope for their future and looked forward to the day when they would raise a family. In spite of the joy Agnes imagined a family would bring her and George, the very mention of family had always reminded her of Quentin, and to re-live those fraught and painful days of his being taken from home, and leaving him behind when she left for New Zealand. Annie was the only family Agnes had until she and George married.

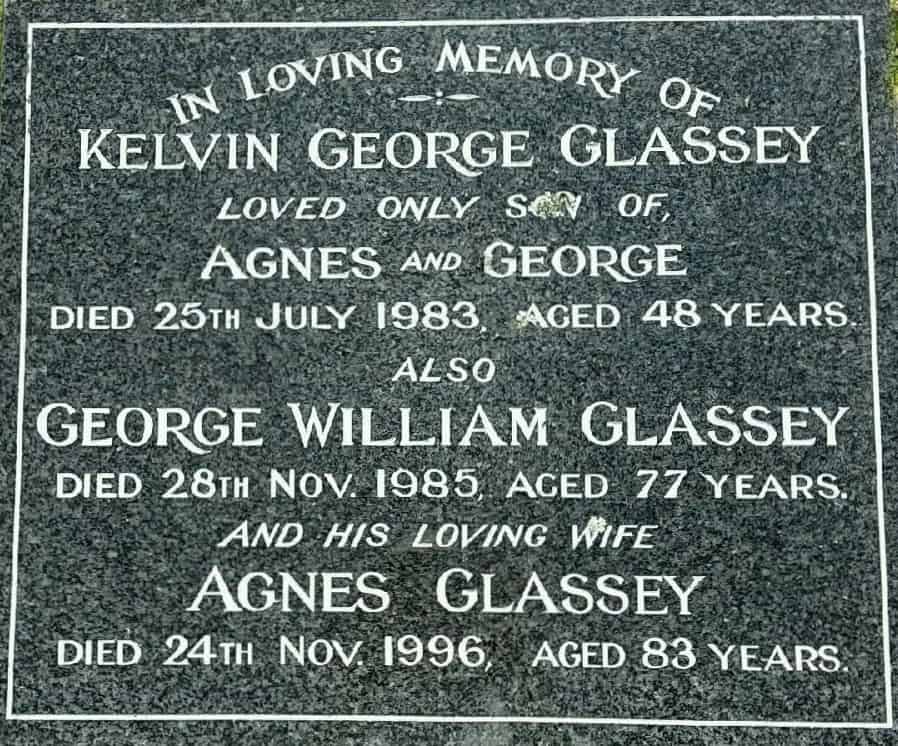

Whilst at Springfield the Glassey’s raised three children – a son and two daughters, Barbara being one of them. After the war the Glasseys moved into Christchurch city where George ran a butchery in St Albans for a few years before moving to another around 1947 which was positioned on the (Main) North Road at Belfast. By 1954 the Glassey’s had relocated to the North Island, to Opunake in Taranaki. While there George’s son Kelvin, also a qualified butcher, had joined his father in the business. A subsequent move to Hamilton in the late 1960s heralded the end of the Glassey’s involvement in the butchery trade. Kelvin went in a new direction becoming a primary school teacher while George took on a temporary mail delivery business. By 1970, the Glasseys had made their final move to 12 Swaffield Road in Mangere, Auckland. Kelvin was teaching at a local school while both Barbara and her sister had both got married and in the throes of starting families of their own. It was George and Agnes’s time to enjoy a well earned retirement and the pleasure their grandchildren would bring. In July 1938 the family were shocked by the unexpectedly passing of Kelvin at the age of 48. Having worked together closely for many years, Kelvin’s death no doubt had a significant affect on George Glassey. Sadly, George W. Glassey died just two years later in 1985 at 77 years of age leaving Agnes (73) to soldier on alone.

Agnes Glassey being Edinburgh born was made of sturdy stuff with a Scottish constitution to match. Her up-bring in austere circumstances, the loss of her mother and brother Quentin at an early age, her separation from siblings and placement in an orphanage, and her relocation at 16 years of age to the other side of the planet as the Great Depression descended, amounted to a life that many adults of far greater maturity and experience would not have handled as well as Agnes did. The untimely death of her only son Kelvin, followed closely by husband George, was still not enough to wilt Agnes Glassey who stoically carried on, fortified by her trademark Scottish pragmatism and resilience. Whilst some comfort was garnered in having her older sister Mary Matthews and younger brother George Christie Cowan** in New Zealand, I suspect one of the great unspoken sadness’s in Agnes’s life was not having had the opportunity to know and share in her brother Quentin’s life, a brother whom she would outlive by many years.

Agnes’s story to be continued further down ….

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

QUENTIN’s story

Matron Agnes Bitten was the nurse who had collected two year old Quentin Cowan from the Cowan’s Albany Street home in Dundee after his mother Mary Anne Cowan died. In piecing together what little I could find out about Agnes, known to her family as “Aggie”, I learned that she had been a life-long spinster whose occupation as a maternity and private nurse was complimented with a naturally compassionate nature, especially towards the children of mother’s and families not able to adequately look after their own.

-

Matron A. A. Bitten

Agnes Annie Bitten was born on 15 February 1885 at Grantham, Lincolnshire, the second eldest of five siblings born to Machine Driller, Walter John BITTEN (1843-1933) and his wife Annie Marie WILLCOCK (1851-1939). Agnes’s had three siblings, Arthur Ernest (b1880), an Iron Fitter & Turner, Agnes, Herbert Charles (b1887-1982), a Letter Carrier/Messenger, and Ethel Mary (1888-1975) who married Arthur Thomas JACKLIN (1889-1921), an assistant to a Corn Merchant. The Jacklin’s three children Arthur, Ida and Harold were Agnes Bitten’s nephews and niece. In the 1901 Census Agnes was listed as a Dressmaker living at Hill Foot, Great Gonerby, a rural district north of Grantham.

In February 1914 prior to Britain’s declaration of war with Germany, Aggie Bitten then 29, had been hired as a private nurse/companion to accompany her wealthy employer to Argentina. Aggie travelled on the RMS Demerara from Liverpool to Buenos Aires, Argentina where she lived for the duration of the First World War. In June 1918, Aggie left La Plata (the River Plate) in Montevideo, Uruguay on the RMS Highland Laddie and returned safely to London. Aggie then took a position as a staff nurse with the Edinburgh Infirmary in Scotland. During her time in Edinburgh Aggie nursed and cared for numerous children who had been placed in institutionalised care by un-wed mothers, children who had been abandoned children and those whose parents had either fallen on hard times or unable to adequately care for them. By 1920 Aggie was the matron of the maternity wing at one of the Christie Industrial Homes. Her home was a one room apartment in a rather dismal and cold accommodation block of shared facilities, at 142 New Assembly Close in the centre of Edinburgh’s Old Town.

Matron Bitten’s compassionate nature came to the fore when she was called upon to collect two year old Quentin Cowan from his home after his mother died. Perhaps it was the tragedy of the circumstances, or her age and an unrequited desire for a child of her own that motivated Aggie Bitten to take a shine to little Quentin. Whatever her rational, she took on the responsibility of Quentin’s guardianship. For all intents and purposes Aggie would become Quentin’s foster-mother, his teacher, companion and grandmother all rolled into one as she raised Quentin as her own. Corporal George Cowan, who was still serving in the Army, slipped out of Quentin’s life and as far as is known never again featured in his son’s life.

Quentin’s formative years were spent with Aggie at the Maternity Wing and at New Assembly Close. His education was started at a Christies approved local school that accommodated the bulk of the orphanage’s school age inmates, and completed his primary education to a Year 6 or 7 standard (NZ equivalent). Edinburgh is a city greatly influenced by its military heritage, presided over by Edinburgh Castle which in 1920 still housed working military units. Today there are only a handful of personnel largely involved with administrative and ceremonial duties. The citizens of Edinburgh are immensely proud of this history and heritage where some of the oldest regiments in Scotland are still part of the city’s fabric. Quentin Cowan was no different to many other lads who grew up in Edinburgh, bedazzled by the uniforms, the horses, the guns and the skirrl of the pipes whenever the military was on parade or marching through the streets. He very much wanted to join them when he was old enough, undoubtedly encouraged by his “mum” Aggie Bitten.

-

The Cadet Force

With Britain under threat of a French invasion in 1859, and most units of the British Army serving in India following the Indian Mutiny, the Volunteers were formed, a forerunner of today’s Territorial Army. A number of Volunteer units also formed Cadet Companies and schools had also started to form units with at least eight were in existence by 1860.

The title Cadet Force was introduced in 1908 (now the Army Cadet Force) and Volunteers, the Territorial Army. Administration of the Cadet Force was also taken over by the Territorial Army Associations. The First World War bought about a massive expansion of the Cadet Force which the War Office took over the administration of. Later it reverted to TA Association oversight. Today the ACF has a membership of some 39,000 cadets (aged 12-18) and 9,000 adults in over 1,600 locations around the UK.

Quentin was very likely introduced to military training at school as a number countrywide and throughout England had a Cadet Force Company that was linked to one of the local Territorial Army battalions. In 1932 Quentin, then aged 12, joined the Cadet Force Company of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) territorial battalion in Edinburgh, the oldest Cadet Force Company in Britain that can trace its history back to 1859. The training provided was a healthy mix of basic skills (a la the Boy Scouts) together with drill, parades, camps and fun – plenty to engage 12–17 year old teenagers.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

-

Leaving Edinburgh

The last quarter of 1936 signalled the end of almost 20 years Matron Aggie Bitten had lived her one room apartment at New Assembly Close in Edinburgh city, the last twelve with ever growing Quentin, and all the while heading the Maternity Wing at the children’s home. Aggie was 52, tired and felt it was time to return to her home county where she could be nearer her ageing parents and sibling’s families. The news of ever increasing intentions in Europe and talk of a possible war which Britain could possibly be drawn into was also disquieting for Aggie. The country was still in the grip of the Great Depression, shortages of everything from flour to fuel. It is hardly surprising that Aggie Bitten was keen to ‘circle the wagons’ and get herself and Quentin settled closer to her parents and family, then come what may. Aggie responded to an advertisement for a Nurse/Companion to an elderly owner of “The Elms” at 50 High Street in Market Harborough, Leicestershire. Conveniently for Aggie, The Elms was also only 40 miles from her parent’s home at Grantham, the town of Aggie’s birth in Lincolnshire. The move could also prove worthwhile for Quentin as Grantham was only 45 minutes by road to Sobraon Barracks in Lincoln, the headquarters of the Army’s Cadet Forces, and The Lincolnshire Regiment. At Christmas 1936, Aggie and Quentin left Edinburgh for Grantham.

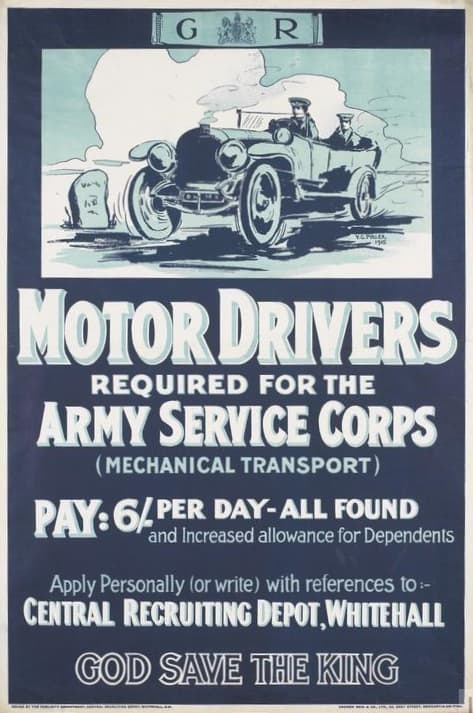

At the time Aggie and Quentin arrived in Grantham, a hand-bill was being widely circulated around the town. It read as follows:

“TO THE YOUNG MEN OF LINCOLNSHIRE”

“If you wish to lead an honourable, useful, active and happy life With excellent prospects of promotion, I invite you to join your County Regiment, the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment. The Infantry is the back-bone of the Army and the Royal Lincolns have a record and traditions which are second to none.

You may apply to join the Regiment if you are between 17 and 30 years of age, provided you are fit and healthy. If you have been in the Army previously, you may be able to deduct your former full time service from your present age in order to bring you within the age limit for enlistment.

Terms of Service. The Army offers you a secure career with a pension after 22 years service. You may either enlist for 22 years with the right to terminate your service after each period of three years, provided you give six months notice; or you may enlist for three years with the Colours and four years on the Reserve.

Pay. The amount of pay a soldier receives depends on how long he undertakes to serve. The minimum rate of pay on enlistment for men who undertake to serve:-

- 3 years is 63/- a week)

- 6 years is 77/- a week)

- Plus free food and clothing, and if married and extra 42/- per week (NZ$4.20)

A skilled soldier will get considerably more.

The Regimental Band. Boys between 15 and 17 years of age, who pass the necessary intelligence tests, may now enlist for service with the Regimental Band for a period of 6 years with the Colours and 3 years on the Reserve. Pay for boys’ is from £1. 1s. 6d (NZ$2.16 cents) per week, plus free food and clothing. Bandsmen may enlist up to the age of 33.

-

Enlistment

Quentin had very much enjoyed his time with the Cadet Force Company of the Black Watch. This seemed to be an opportunity to take up soldiering as a profession and so he considered the possibilities over Christmas and presumably discussed his decision with Aggie.

With the country still emerging from the Great Depression of the 1930s and the priority was to re-build the Army. As far as enlistment was concerned, provided there was no obvious criminal record, outstanding arrest warrants, or parental permissions required for underage enlistment, young volunteers like Quentin were required in their thousands to fill the depleted ranks of the post-war British Army. A young man who presented as Quentin did – fit, schooled to a reasonable level and who appeared to come from a stable background, was highly unlikely to have his enlistment challenged, BUT … Quentin had doubts that his origins might be an impediment.

-

What’s in a name?

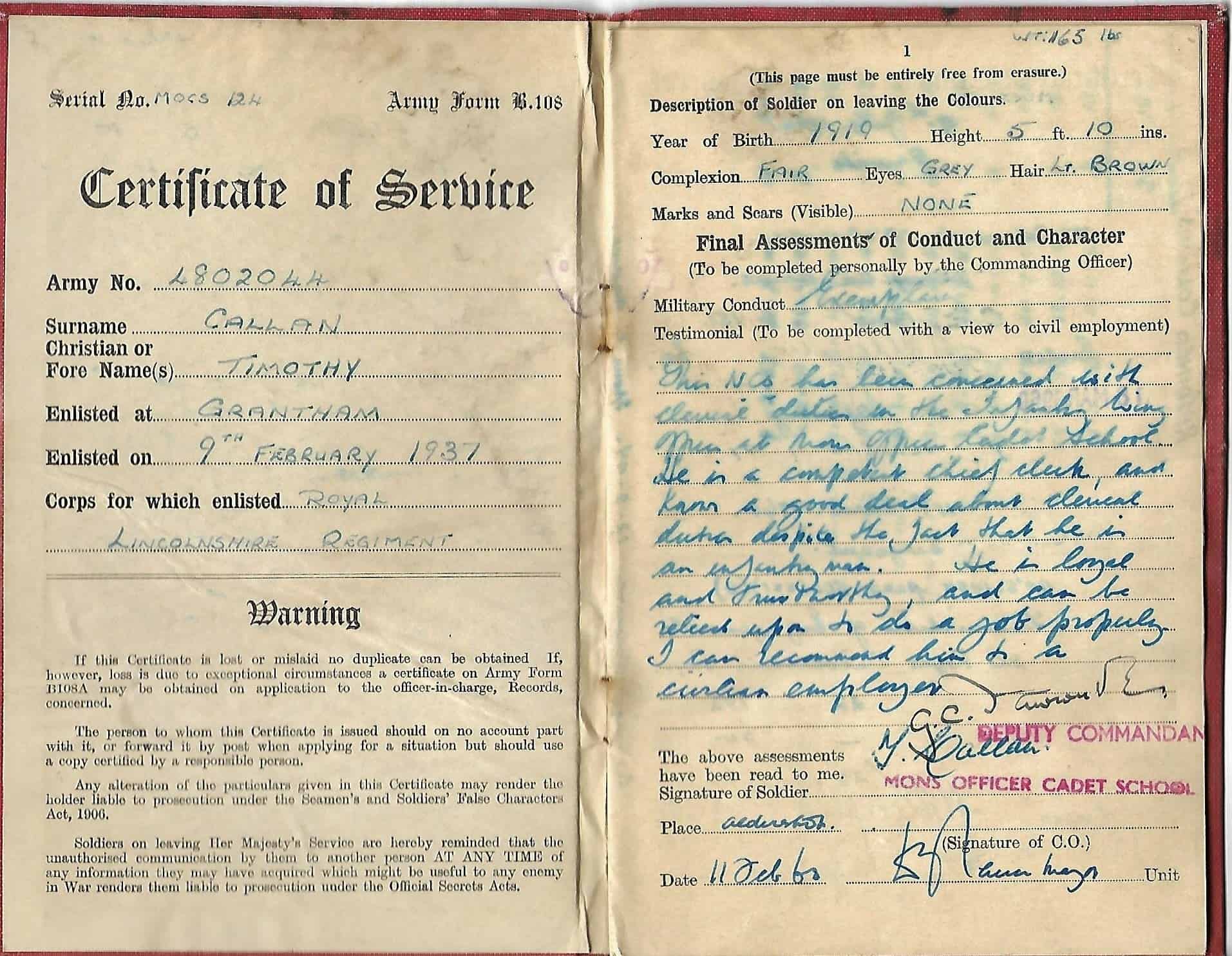

As I attempted to follow Quentin’s movements throughout his life via Electoral Rolls and Censuses, luckily I had the advantage of reading his Record of Service (ROS) first, one of the items given to Agnes Glassey. Every service person receives an ROS on discharge from the military but Quentin’s was unique in that it was made out in the name of “TIMOTHY CALLAN.“ This alerted me to the fact this was not going to be a straight forward case. Census references I found had included QUENTIN MORRISON COWAN and his Death Certificate stated his name to be QUENTIN TIMOTHY CALLAN. While this quandree initially caused me some grief, but by the time I had an understanding of Quentin’s convoluted background, I understood (I think) why the variations.

Quentin COWAN he was named at birth in 1920 by his then legally married parents, Mary Anne Christie Cowan and George Black Cowan. His middle name of “MORRISON” appears to have been a later addition, the married name of his father George’s Cowan’s mother Jemima who was re-married to Robert Morrison. Since Quentin would not have known of his mother’s re-marriage until much later in his life, he likely added it himself as an acknowledgement of her?

In contemplating an Army career, there were perhaps three compelling reasons for Quentin changing his name. Firstly, a name change would remove the potential for any association or connection to his biological father, George Black Cowan. The former ASC Corporal and Bakery NCO is believed to have created for himself a less than favourable reputation in the Army. For all intents and purposes, Quentin had been an orphan who was fostered out of the Cowan family upon the death of his mother. George Cowan had been responsible for putting the family in to care and had then apparently washed his hands of them. Barbara’s mother Agnes could not ever recall seeing her father after they went to Christies. This could have distressed/angered Quentin once old enough to understand and may have entrenched ill-feeling towards his father.

The second possible reason is that Quentin was unlikely to have had any documentary proof (birth certificate) of who he actually was. Born in Scotland, removed from the family home as a baby, raised in the care of a foster-mother (Aggie Bitten), and removed to England probably gave Quentin sufficient reason and latitude to create an identity, one that was unlikely to be challenged at a time when Britain was moving towards a war footing. If he was unable to prove on paper who he was, changing his name would conveniently eliminate his ability to prove (or disprove) that he was “Timothy Callan” and the Army was not about to waste much time proving otherwise.

The third possibility has to do with Quentin’s legal status. He was ‘taken in’ by Agnes Bitten at two years of age with no apparent formality. As far as I could determine there was no subsequent move to legally adopt him.

Anecdotal evidence from Barbara H. suggested one another possible reason was an accident she was vaguely aware Quentin had. His injuries apparently were substantial and necessitated an extended period in hospital and facial surgery. Were he to be denied entry into the Regular Army (and the potential to serve overseas), changing his name and re-enlisting elsewhere in the UK could effectively mask any association with the injured “Quentin Cowan”? These however were all questions that only Quentin or his foster-mother Aggie Bitten could answer, had they still been alive.

-

Service with the ‘Colours’

On 9 February 1937, Quentin Morrison Cowan at 16 years 10 months of age fronted the Recruiting Officer at Grantham to enlist with the Lincolnshire Regiment (Lincs. Regt). Quentin stood 5 foot 10 inches tall (179 cms!), had a fair complexion, grey eyes, light brown hair and was physically fit and able. After some preliminaries, Quentin was Attested for service by swearing an Oath of his Allegiance to His Majesty, the King, and signing the dotted line of his contract to serve. He had committed himself to 22 years of ‘Service with the Colours.’ From that time on QUENTIN MORRISON COWAN ceased to exist while QUENTIN TIMOTHY CALLAN emerged, to be known only as TIMOTHY “Tim” CALLAN for the duration of his military career. However he remained “Quentin” or “Q” to both Aggie Bitten and Michael.

-

The LINCS Regiment

4202044 Private Timothy CALLAN was a Regular Army soldier of the 1st Battalion, the Lincolnshire Regiment. For the next four years and 295 days, Tim Callan would complete a variety of training courses, field exercises and camps in order to equip him as a professional infantry soldier of the 1st Battalion. He also passed his 3rd Class Army Education Certificate, a compulsory requirement for promotion to Lance Corporal (L/Cpl). During his initial period of service, the Second World War had commenced and the bulk of the land, sea. First up was Basic Training at the Lincolnshire Regiment’s Barracks.

The Lincolnshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army raised on 20 June 1685 as the Earl of Bath’s Regiment for its first Colonel, John Granville, 1st Earl of Bath. In 1751 it was numbered like most other Army regiments and named the 10th (North Lincoln) Regiment of Foot. After the Childers Reforms of 1881 it became the Lincolnshire Regiment after the county where it had been recruiting since 1781.

After the Second World War, the regiment was honoured with the name Royal Lincolnshire Regiment, before being amalgamated in 1960 with a series of smaller regiments to form the Royal Anglian Regiment. ‘A’ Company of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Anglians continues the traditions of the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment.

-

Posting to the ‘Guns’

Within the next 24 months preparations for a possible war with Germany was becoming more likely as the belligerent country threatened the stability of Europe. When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, all regular and territorial regiments were mobilised. The Lincolnshire Regiment committed the 2nd, 4th, and 6th Battalions to serve in France whilst the 1st Battalion, which was stationed in India at that time, would not not see any action until 1942. Because a soldier had to be 20 years of age before he was allowed to serve overseas, Pte. Callan was confined to employment with units tasked with constructing home defences in preparation for an anticipated German invasion of mainland England. It would be only a matter of months before Tim turned twenty.

In 1940 the Lincolnshire Regiment raised two additional battalions, both of which were converted into specialist arms of service. The 7th Bn became the 102nd Light Anti-Aircraft (LAA) Regiment, Royal Artillery (RA) on 1st December 1941, and the 8th Bn became the 101st Anti-Tank (ATK) Regiment, Royal Artillery. Now a L/Cpl, Tim Callan was transferred to the Royal Artillery’s 102 LAA Regiment in December 1941 for coastal anti-aircraft defence duties. He remained with the RA for the next three and a half years engaged in home defence protection of strategic assets until the end of the war. From mid 1945 until July 1946 his RA unit was attached to the Army Air Corps (AAC). Formed in 1942 the corps initially comprised the Glider Pilot Regiment and the Parachute Battalions (subsequently the Parachute Regiment), Air Landing Regiments and the Air Observation Post Squadrons. In March 1944, the SAS Regiment was added to the Corps. Having completed his mobilisation commitment, L/Cpl Callan was discharged from Active Duty, transferred to the Army Reserve on 09 July 1946, and then placed on leave. Quentin returned to Grantham and his “mum” Aggie Bitten.

Medals: Defence Medal and War Medal, 1939 -1945

Units: Lincolnshire Regiment (1st Bn), Royal Artillery (102 LAA Regt), Army Air Corps (Para Battalion, 3rd Para Brigade, UK)

Total Service: 9 years 151 days

Highest Rank: Lance Corporal

-

15 Orlando Road, Carlton

Following the death of her employer at The Elms, Aggie Bitten’s live-in situation ended and she returned to Grantham to stay with relatives temporarily while she looked for suitable permanent accommodation for herself and Quentin. Quentin’s return to the Army Reserve meant that he would need a permanent base as his accommodation in camp was only transit. Aggie and Quentin set about finding a house in the Lincolnshire/Nottingham area that would be handy to both the Regiment’s Sobraon Barracks and Grantham in Nottingham where Aggie’s family lived. They house at 15 Orlando Road in the Nottingham suburb of Carlton was settled on which was roughly midway between Grantham and the Barracks. Aggie started working again as a child carer at home, or in the client’s family home, whilst parents worked.

-

My ‘cousin’ Michael

Aggie’s only sister, Ethel Mary BITTEN (1888-1975), married Thomas Arthur JACKLIN (1889-1921) whilst Aggie was away in Edinburgh. In 1944 Ethel and Thomas’s only daughter, Ida Annie JACKLIN (1912-1991), found herself in the family way while the biological father recoiled from his inferred paternity and made himself scarce. When Ida’s mother learned of her daughter’s situation she was incensed and refused to allow Ida to have the baby. Ida being in her early thirties and capable of making her own decisions, was not about to be told. Not wanting to distress her parents any further, Ida had no option but to leave as she had no intention of giving up (or worse!) her child, and so she left.

Her Aunt Aggie Bitten being clearly experienced in dealing with such matters, became her confidant and resulted in Ida going to live with Aggie and Quentin. Ida gave birth to a healthy son on 30 November 1944 whom she named Michael Ian MILLS. Ida could ill-afford to remain out of work so as soon as Michael had been weaned, Ida returned to work while Aggie took care of Michael. The consequence of this arrangement was that Michael grew believing Aggie Bitten to be his “Nanna” and Ida his sister! He would be told the truth when he was much older and able to comprehend the reasons for his circumstances.

From this beginning Quentin and Michael forged a very close bond. Michael would refer to his “Uncle Quentin” while also considering him his “dad.” Throughout his boy-hood Michael idolised Quentin, as a son would an older brother. He would eagerly await Quentin’s return from camp, a field exercise or from an overseas posting, and was always thrilled whenever Q arrived. Michael particularly enjoyed the special occasions like holidays or picnics on the rare occasions that he, Quentin, Aggie and (‘sister’) Ida could all be together. It would be fair to say Quentin played a huge part in Michael’s life both as a child and later as an adult. Perhaps Quentin could also empathise with Michael’s circumstances in that they were in some ways not too dissimilar to his own growing up.

Michael remained with Aggie and Quentin until the age of 22 at which time he took the plunge and married Diana BARRATT on July 30th, 1966. Guess who was Michael’s Best Man? … correct, his Uncle Quentin. Michael and Diana then moved into their first home at 72 Gunthorpe Road, Gedling.

-

Territorial Army (TA) – Re-enlistment

At the end of World War 2 Britain needed all available manpower to rebuild its industry and economy. The government therefore demobilised its wartime conscripts as fast it could in consonance with post-hostilities commitments, but its actions nonetheless left the British Army with an acute manpower shortage. As a means of filling the depleted ranks, the British government continued limited conscription after the war and in 1947 approved the country’s first ever peacetime compulsory service in an effort to build a large reserve army. Because the first National Service intakes in 1949 would not move to the reserve until 1950, the government realised it needed to take interim measures to cover the Army’s immediate manpower requirements.

As a result Quentin, known as Tim Callan, was re-enlisted into the regular army in March 1947 and re-joined his former battalion of the now Royal Lincolnshire Regiment** to train and exercise in preparation for their deployment to the Middle East.

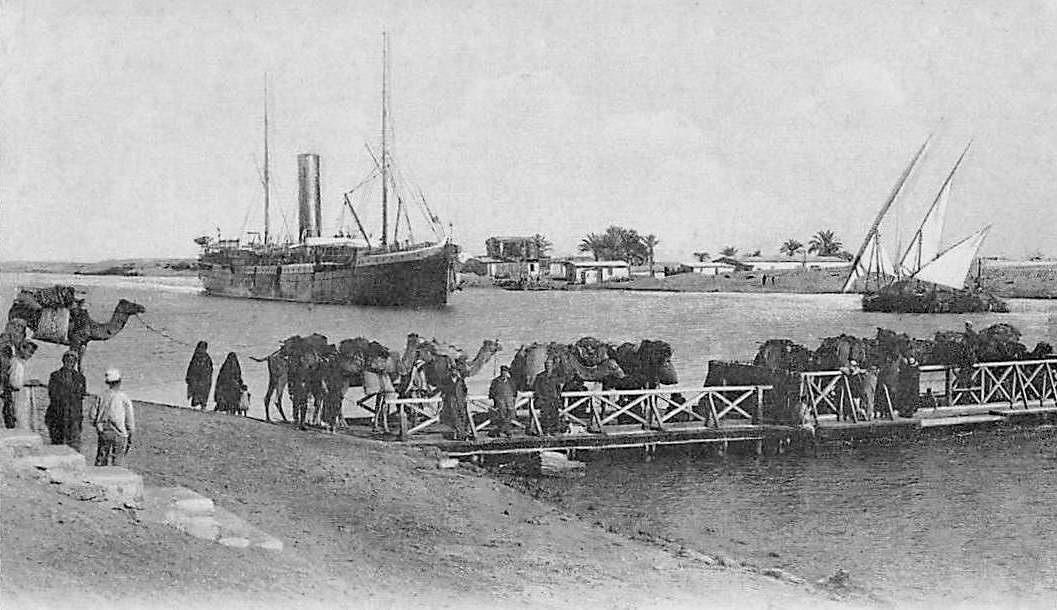

MELF – Middle East, Egypt

After 1945 the units of the Middle East Command were reorganised to meet the existing threat and tasks in the Middle East. The MEC was re-titled the Middle East Land Forces (MELF) which commanded all British forces in the Suez Canal Zone until the early 1950s, and in Libya until 1957. The Suez Canal was an economic and strategically vital route for both Middle Eastern oil and trade with the Far East (Malaya, Singapore, Japan etc).

Britain maintained a military presence in Egypt to protect the canal under the terms of a treaty signed in 1936. However, Egyptian nationalists resented the British presence in their country. As early as 1945, riots had broken out and the first British soldier was killed there. Withdrawing from the cities, British forces concentrated in the area immediately adjacent to the canal, known as ‘the Canal Zone’, the centre of which was Ismailia. Then in October 1951, the Egyptian government increased pressure on the British and repealed the 1936 treaty. Between 1950 and 1956, the violence escalated: 54 servicemen were killed and many others injured.

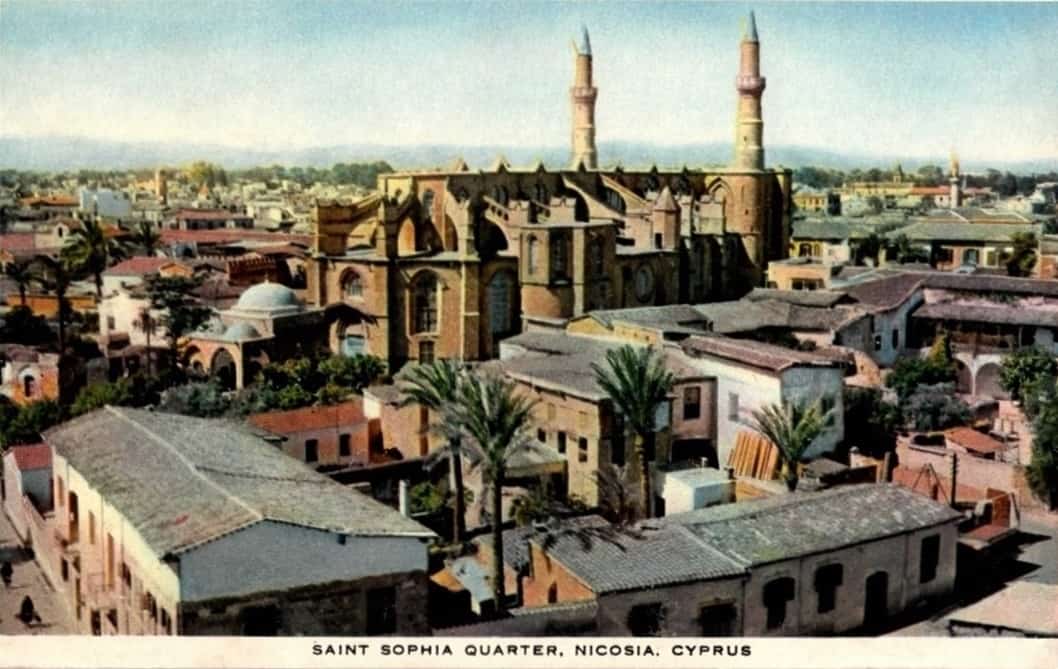

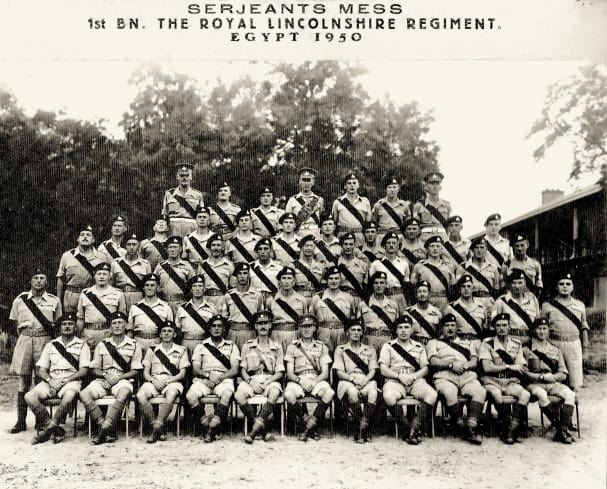

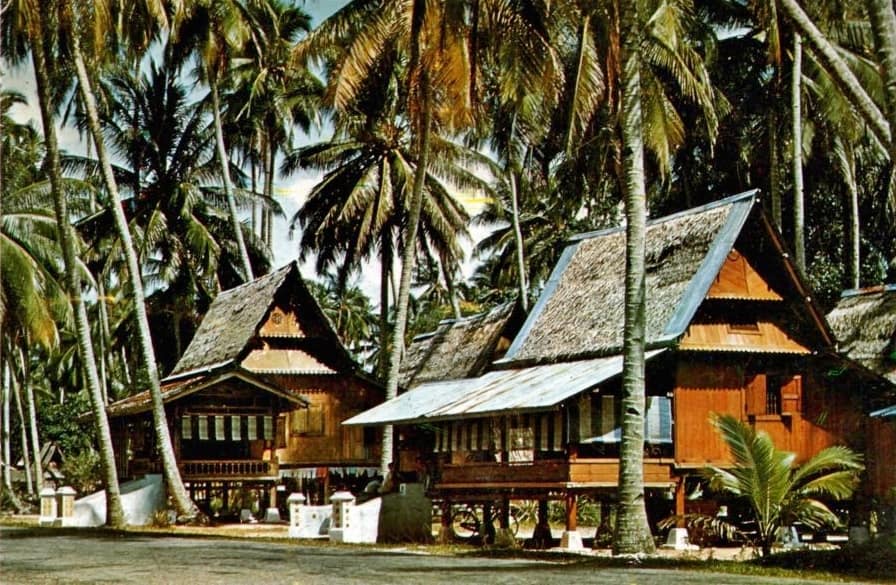

An operation to disarm the police in Ismailia in January 1952 resulted in the deaths of 40 Egyptian paramilitaries, and the deaths and wounding of several British soldiers. Whilst regular brigades of armour and infantry were deployed to maintain the security of the Canal itself, security forces were garrisoned in Cairo, on the island of Cyprus and in Aden, Saudi Arabia to contend with outbreaks of violence by revolting dissidents. The battalions of the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment were rotated through this duty every on two years. It was to be Sgt. Callan’s first overseas posting, serving with the Cairo Garrison from Feb 1950 to May 1952. At the of his posting Sgt. Callan returned to Lincolnshire and garrison duties with his battalion.

By 1954, the garrison in the Canal Zone numbered around 70,000 British soldiers which became difficult to supply without the support of the Egyptian government. Negotiations began and an agreement was reached on 19 October 1954 to end the British occupation. Britain was given 20 months to withdraw from the country.

Awards: Nil

Service with MELF: 2 years 79 days

Highest Rank: Sergeant

-

Para Training

Whilst with the AAC, Sgt. Callan had applied to complete a Parachute Training Course but was told he could attend one when he returned from Egypt. His impending deployment to the MELF had put the brakes on that. His aim had been to join one of the Parachute Battalions he had seen in the ACC. Airborne soldiers were expected to fight against superior numbers of the enemy, armed with heavy weapons, including artillery and tanks. Hence, training was designed to encourage a spirit of self-discipline, self-reliance and aggressiveness. Emphasis was placed on physical fitness, marksmanship and field craft. A large part of the training regime consisted of assault courses and route marching. Military exercises included capturing and holding airborne bridgeheads, road or rail bridges and coastal fortifications. At the end of most exercises, the battalion would march back to their barracks. The ability to cover long distances at speed was expected: airborne platoons were required to cover a distance of 50 miles (80 km) in 24 hours, and battalions 32 miles (51 km)

Shortly after he returned to the Regiment, having passed the entry pre-requisites of medical and physical fitness, he attended the twelve-day basic parachute training course at No. 1 Parachute Training School, RAF Ringway. Initial parachute jumps were made from a converted barrage balloon and finished with five parachute jumps from an aircraft. Anyone failing to complete a descent was returned to his previous unit immediately. Those men who successfully completed the parachute course were presented with their maroon beret, badge and parachute wings. Sgt Callan passed the course with flying colours and received his coveted beret and ‘jump wings.’

-

BAOR – Germany