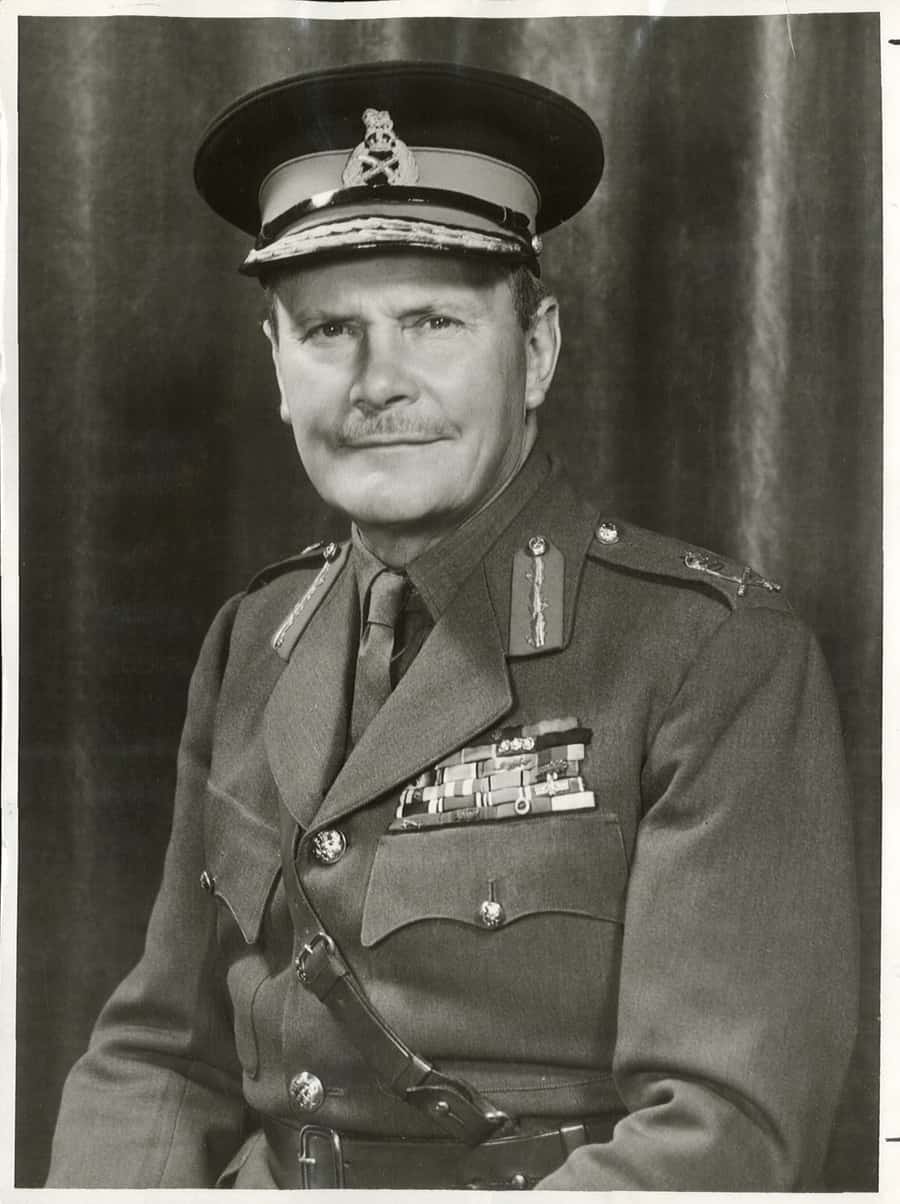

7095 ~ JAMES CYRIL HENLEY, MBE, OStJ, DCM, ED

Some details of this story remain confidential by request.

In the Beginning …

A phone call a few days after Anzac Day this year from a rather distressed lady (M.) from Napier resulted in her relating to me the story of her family’s anguish after discovering their deceased father’s war medals were missing. Upon further questioning, M. said that she had found out the medals had been sold! Of course this had been done without the knowledge or concurrence of the family members concerned – sound familiar?

I regret to say I have been confronted with similar circumstances all too frequently – the only thing that differed in each case was the complexity of circumstances that lead to the disposal of medals in the first place, and the time elapsed before any action was taken to either report the loss or initiate some action to recover the medals.

Now that this case has been concluded I can relate the circumstances that led to the medals being sold. A discussion between a few of the family members who had attended this year’s Anzac Day commemoration service had resulted in questions being asked, “.. so, where are Dad’s medals? – who’se got them? – we haven’t seen them for ages.” In fact as my questions were answered it seemed their father’s medals had not been seen in any one place by the family as a whole since James Henley’s funeral in 1994!

When James and wife Marjorie Henley had been alive the medals had hung in pride of place in the lounge of the family home. Everyone was used to seeing them there, passing them daily while they were living at home and never really giving them another thought. Once the Henley siblings had grown, gone their separate ways and started families of their own, “Dad’s medals” had never been a topic of conversation. There was also no question of the medals being worn by any of the family since they had been professionally mounted and framed under glass, so were inaccessible for that purpose anyway.

As life gets in the way and our memory’s cloud the details once part of our daily lives, recalling the what, when and where of something like “Dad’s medals” can quickly fade into the background – until we are prompted to remember. Such was the case with Mr Henley’s medals.

The post Anzac Day service discussion regarding “Dad’s medals” had suddenly become a hot topic in M.’s house, not just because no-one had seen them but because of the recollection that their father had been given a medal for bravery in the war, something all (most?) of the family had been extremely proud of. The consensus of opinion was that someone in the family must have the medals but no-one involved in the discussion was too sure if that was the case. Long term custody and responsibility for “Dad’s medals” was something that had just never come up.

History and experience of these sort of situations shows that 9 times out of 10 the answer will be found within a family (immediate or extended) – so generally, not a problem. But when there is a problem which perhaps points toward the possible loss of high value or sentimentally significant items, the necessity for families to have an agreed succession plan of guardianship that every member is aware of, is essential to avoid future grief.

There had been no such plan for Mr Henley’s medals, in other words there was no mutually agreed or appointed kaitiaki (caretaker/custodian) of the Henley family’s taonga (precious, highly regarded heirlooms). Their assumption had been that after a funeral, guardianship of a deceased person’s personal and/or precious belongings usually becomes the responsibility of the eldest son (or daughter in the absence of a son) as is the usual way of things. Since the funeral no-one had spoken again of “Dad’s medals” – out of sight, out of mind?

Extra-ordinary medals

The plight of the Henley’s medals might not have been of such great concern had they simply been the standard Second World War campaign medals that were issued (un-named) to all Commonwealth forces in their hundreds of thousands, but James Henley’s medals were EXTRA-ORDINARY !

James Cyril Henley (universally known as ‘Jim’) was an early starter when it came to wearing a uniform. A St John Ambulance Cadet at primary school, Jim later enlisted in the army’s Territorial Force once old enough. He had served overseas during WW2 in Egypt, Crete and North Africa, and continued to serve both the Army and the Order of St John after his return home.

While Jim’s war service alone could be considered extraordinary, his whole life in fact could be characterized as one of service – extra-ordinary, humble and selfless service. It would not be an understatement to say Jim Henley’s life (which included his leisure time) had a singular focus – an unwavering dedication to the service of others, a life of giving which was reflected in part by a most impressive and unique array of medals.

Jim Henley’s first, and venture to say, most significant accolade was bestowed upon him for extraordinary war service in North Africa. Jim had been decorated “for distinguished conduct in the field.” The Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) is awarded for distinguished acts of courage and gallantry “in the face of the enemy”, and is ranked second only to the Victoria Cross. Jim Henley’s DCM was one of only 109 DCMs (and one Bar) awarded to New Zealanders during the Second World War, making it a rarity when you consider the number who served. Around 140,000 NZers served overseas in WW2; 100,000 more served at home with the Home Guard and in other essential military training, defence and supporting services. The significance and rarity of this award can be further placed into perspective when you consider that over 60 million men and women were killed or died in the space of just six and a half years of war. Five Victoria Crosses were awarded to NZers in WW2.

In the years following the war Jim Henley’s continued selfless service was recognised on a number of occasions. He was the recipient of three Royal honours plus decorations for long service in both the NZ Army and the Order of St John, making his medal group one not duplicated anywhere else in the world. No doubt the reader can begin to appreciate the sort of interest Jim Henley’s medals could generate among medal collectors in New Zealand were they available for sale. To an international market, a medal group such as this could potentially realise a price three times that a New Zealand collector might pay. Jim Henley’s medals are not only unique taonga to the Henley family, they are also part of New Zealand’s social history and to that end are valuable – very valuable without putting too finer point on it. For them to leave New Zealand would require express permission of the Ministry of Culture and Heritage. Without this permission, removal of a significant medal group from New Zealand is illegal and constitutes an offence for which a prosecution may result.

But wait …. there’s more !

M.’s tale of woe unfortunately did not end with the medals. Aside from these M. said her father also had a suitcase in which he kept all his photographs, letters, papers, mementos and paraphernalia associated with his Army and St John Ambulance service, the RSA, life saving, plus his post-war teaching career. This was she had also gone with the medals.

When asked M.’s brother confirmed he did have the medals. More probing questions followed, –“what do you mean DID have the medals?” For whatever reason brother/eldest son/uncle had decided without reference to SELL the medals that had been under a bed in his house for the last 22+ years. “Why?” … apparently because no-one had shown any particular interest in them, so …. “and the case of photos and papers etc?” …. these had been sold with them! Needless to say M. and the rest of the family were aghast when they heard this, and somewhat angry. Probably just as well that brother/eldest son/uncle lived many miles away at that moment.

MRNZ .. can you help ?

It was at this point that M. had called MRNZ for help. My initial reaction was one of sympathy but felt there was little I could do. I told M. that we at MRNZ did not search for family medals; rather we attempt to reunite those that have been found with descendant families. Besides, the sale of the Henley medals had occurred as I discovered, over a year ago and as far as I was concerned the situation had all the hallmarks of a lost cause. The medals and suitcase of associated memorabilia would likely be long gone, probably to an international collector or auction house. To buy a rare medal group is one thing but to also have a suitcase of supporting documentation and photos that provides provenance, is a collector or dealer’s dream. An off-shore sale would also realise a considerably higher than return than if sold in NZ.

When I spoke with M. her distress was apparent. After I had outlined the realities of the situation to her, M. responded“… but, is there anything you can do to get them back?” I had to say in all honesty, that in the unlikely event the medals were still in NZ they would probably in the hands a serious collector. Once a collector has secured a rare medal or medal group such as Jim Henley’s, they would be most reluctant to part with it, if indeed you could find out who the buyer or subsequent owner was. The ownership of rare and/or valuable medals is a very closed shop.

While I said that we did not search for medals, this case intrigued me and was one I would at least try to find out where the medals had gone. I left M. with a number of questions to get answers for that would hopefully help me build a picture of exactly what had been in the medal frame since she had been unable to tell me exactly what medals her father had, other than that he won a bravery medal. What was in the frame? when were they sold? to whom were they sold? how much was paid? and so on, would all be useful. I left M. saying I would do whatever I could but “don’t hold your breath” …. what a situation! .. where to start?

Note: A salient lesson here for those who treasure their family’s medals or any other heirlooms for that matter – know what it is you have, how many there are, where they are, who in the family has responsibility for them and, photograph everything in detail (close-up). This is your support for any insurance claim should it come to that.

Starting the search

To find out exactly what Jim Henley’s medal group was made up of I first turned to the Auckland War Memorial Cenotaph website for his basic service description. On opening the profile page of 7095 JAMES CYRIL HENLEY I saw the following message:

“I am the eldest grandchild of James Cyril Henley and have just discovered that my Grandfathers significant medal group including DCM and his WWII personal memoirs and photos were sold. I am endeavouring to have these taonga returned to our family. If you have any information that may help please contact me on the following: (phone number) – John H… etc.

I then approached NZDF Personnel Archives & Medals Section for a breakdown of Jim Henley’s service and medal entitlement. The very accommodating senior subject specialist, Team Leader Karley, was able to answer my questions in detail – as always, great service from PAMs.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

James Cyril Henley, known universally as Jim, was born at Birkenhead Auckland in July 1913 to parents Albert Edward HENLEY (a dairyman) and Kate PARRISH, both also born and raised in Birkenhead. In due course the Henley’s had raised a family of four children – Albert Edward Jnr. (1909-1993), James Cyril, Kathleen Daphne ELLISON (1917-1955), and Mary Marjorie HENLEY (1920-1924).

Jim Henley’s working life started during his mid-teens with a variety of farm labouring jobs with his father who was a share-milker on a north Auckland dairy farm. In the early 1930s Jim settled into a regular suburban based job as a “Milk Roundsman” – a Milkman or Milk Vendor, as most now know them, although in this day and age home delivery of milk and cream bottles/cartons/plastics is fast becoming a rarity and no doubt will die out completely once the current generation of mobile vendors retire.

Military service

Jim’s introduction to military service also started during his school days. Most NZ high schools at that time required all boys from the age of 14 to be enlisted into the school’s Cadet Battalion. These school battalions had been the result from the shortcomings of the country’s preparedness for WW1 being identified. Jim was enlisted into the 15th North Auckland Regiment’s Cadet Battalion, something he also enjoyed as he was able to apply many elements of his St John training. Apart from continued attendance at St John, when Jim turned 18 in 1932, he was then old enough to to pursue his army interests that had developed while he was in the Cadet Battalion.

7095 Private James Cyril Henley enlisted with the local territorial army unit at Arch Hill, Auckland in 1936 – the 1st Auckland Infantry Regiment. It followed that his St. John training would pre-determine his Corps specialisation as a Medic in the army’s NZ Medical Corps (NZMC). Pte. Henley was placed with the 1st Field Ambulance, NZMC.

War Declared – 2 NZEF mobilised

In the three years to date that Jim Henley served with the Auckland Infantry Regt. (AIR) he had acquired a number of formal medical qualifications. These, together with practical experience that he continued to acquire as a serving member of the St John Ambulance Brigade, saw him fast tracked through the ranks, first to Corporal, Section Commander and then to Platoon Sergeant of the 1st Field Ambulance. Sgt. Henley’s experience as a medical subject specialist, an instructor and Corps senior NCO took on a very different perspective as the clouds of war gathered for the second time in a century – suddenly the potential for real casualties loomed very large. Sgt. Jim Henley found himself having to prepare his volunteer soldiers and medical staff for possible service overseas in a war the New Zealand government was about to commit to.

On 1st September 1939 Hitler invaded Poland. Two days later Britain, France and New Zealand declared war on Germany. Nine days after the outbreak of war, voluntary enlistment for the First Echelon of the Second NZ Expeditionary Force (2NZEF) was opened. The Auckland Regiment (and the Northland Regiment) was called upon to contribute soldiers to the 18th, 21st, 24th, and 29th Infantry battalions of 2NZEF.

As a territorial soldier Jim and the majority of the Regiment’s soldiers were both excited and apprehensive at the prospect of going overseas to fight; most had already mentally prepared themselves to go, a testament to their training and preparation. Sgt. Jim Henley committed himself to serve and enlisted for 2NZEF service on 25 Sep 1939. It was usual for territorial soldiers to relinquish any rank they on enlistment to 2NZEF, or at least have it reduced to the level of their skill and experience when compared to their Regular Force counterparts (RF – full time career soldiers). Jim Henley already had eight years territorial soldiering under his belt, was a well qualified medical SNCO, and instructor of a skills level at least equivalent to, if not superior to, those of his regular force counterparts. As a consequence Jim retained the rank Sergeant on enlistment, and then it was off to Burnham Camp for pre-embarkation medical training for those joining the Field Ambulance crews.

2 NZ Division – Egypt, Greece, Crete, North Africa (Western Desert)

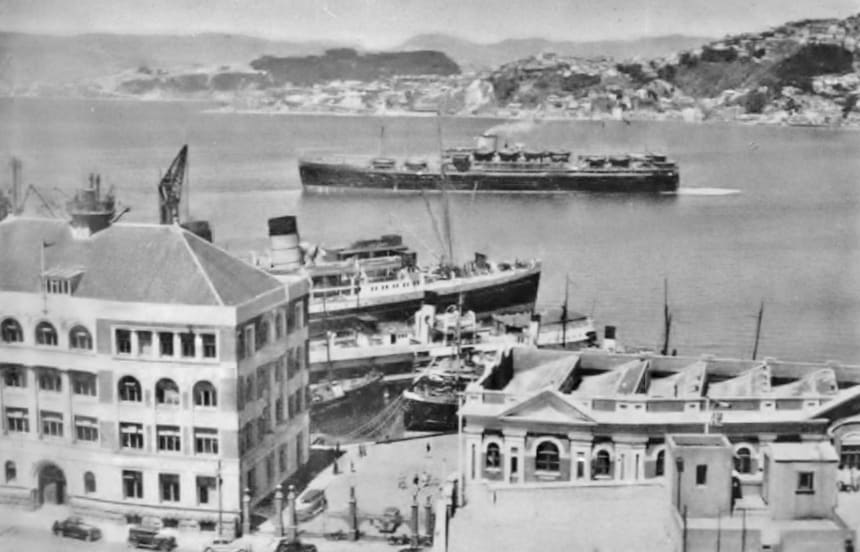

New Zealand had committed a Division (6,500 men) of military assets in support of Great Britain, the NZ forces to be known as the 2nd NZ Division (2 NZDiv). The first of three Echelons had to be ready to sail by the beginning of January 1940. The first echelon would consist of some staff for an overseas base, part of Divisional Headquarters and one infantry brigade group. The second echelon would have the rest of 2 NZDiv headquarters and another infantry brigade group. The third echelon would be the remaining brigade group. Each Brigade was to be drawn in approximately equal proportions from the three military districts. In the 4th Infantry Brigade, for example, 18 Battalion came from the Northern (Auckland), 19 Battalion from the Central (Wellington) and 20 Battalion from the Southern (South Island) Military District.

The plan was for the First Echelon to depart for the Middle East in January 1940 so it could equip and train in much more suitable conditions than could be found in New Zealand. With the arrival of the next two Echelons of units, the expectation was that the 2 NZDiv would complete training in August and be ready for deployment in September 1940. 6500 officers and men would provide 2 NZDiv HQ, some administrative and supply units necessary to establish a base in Egypt, the 4th Infantry Brigade (18th, 19th and 20th Battalions), 27 Machine-gun Battalion, A and B Squadrons of the Divisional Cavalry (Reconnaissance) Battalion, 5th Field Park (Engineer) Company and 4th Field (Artillery) Regiment.

The 1st Echelon were embarked at Lyttelton and Wellington and sailed for Egypt on 5 and 6 January 1940. Sgt. Henley and the 4th Field Ambulance embarked HMT Dunera as part of the 4th NZ Infantry Brigade which sailed from Lyttelton for the Middle East on 5 Jan 1940. The convoy of ships carrying the 1st Echelon arrived at Port Tewfik (100 miles from Cairo) on 12 February, completing disembarkation on the 15th. The NZ Base in Egypt, Maadi Camp, was established approximately 14km south of Cairo as the NZEF’s troop concentration and training base and location for the NZ Division’s headquarters.

Over the next four years 4 Field Ambulance would be involved in all major hot-spots where the NZDiv was deployed to – Greece in 1941, followed by Crete and then the Western Desert from Nov 1941 onward. By the beginning of 1942 the remnants of 18, 19 and 20 Battalions had been withdrawn from Greece and Crete to Egypt. The ensuing three years would see them fighting the German and Italian Axis forces for control of North Africa. This campaign ultimately would result in a further campaign in Italy. With the exception of Greece, Sgt. Jim Henley would be heavily involved in the Crete and North African operations.

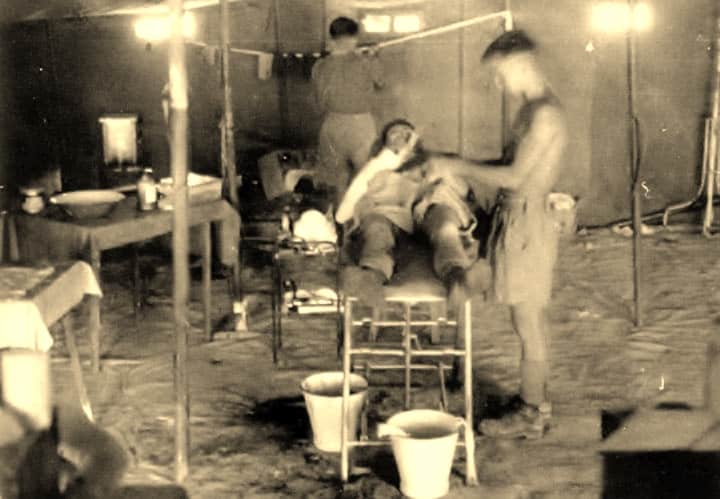

CRETE, March–June 1941

By the 3 March 1941 most of 2NZEF had arrived in the Middle East and on 6-7 March the majority of 2 NZ Division had been committed to Greece and Crete, code named LUSTRE FORCE. On 6 March elements of LUSTRE FORCE commenced landings in Greece to repel the Axis (German and Italian) forces.

Sgt. Henley had been seconded to LUSTRE FORCE however had been retained in North Africa to assist with the planning and preparation of medical services in Greece and for the next phase of operations which was the occupation of Crete. However within weeks of the campaign in Greece commencing it became apparent the situation was becoming untenable. The Allies had been driven from the mountainous heights of Greece back towards the Ionian Sea by a numerically superior enemy. The 8th Army Commander, General Bernard Montgomery, decided to abandon the Greek Campaign and evacuate the Allied troops as quickly as possible to Crete. The German High Command however was one jump ahead and putting the finishing touches on its Operation MERKUR (Mercury) – the Battle of Crete would be the first occasion in history where Fallschirmjäger (paratroops) were used en masse during an invasion.

When the invasion started on 20th May the LUSTRE FORCE medical staff had their work cut out as the Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS), Advanced Dressing Stations (ADS) and Field Hospital were overwhelmed. The first few days of battle produced massed casualties, German and Allies. Many were descending German paratroops, armed only with a pistol (rifles and automatic weapons were landed separately on aircraft – mistake!) had been easy targets for Allied forces and Creteian partisan ground fire. After six days of intense fighting, a lack of equipment and ammunition, poorly communications and several unsuccessful counterattacks (which produced 20% of NZ’s casualties) against a numerically superior enemy supported by attack aircraft, forced the 8th Army Commander to yet again order the Allies to evacuate. They were to withdraw to the south coast port town of Sfakia and would be evacuated by the Royal Navy back to Egypt. The Allies fighting withdrawal to Sfakia took another four days to get their units over a mountain pass and down to the port. On Day 10 and 11 (30 and 31 May) of the battle a lack of available Naval transport almost jeopardised the evacuation.

The withdrawal had been chaotic from the outset. With over 10,000 Allied troops jammed into the small port town, waiting to be evacuated while attempting to keep the lead elements of a pursuing enemy at bay, the evacuation appeared doomed. Fortunately a tactical error by the Germans who misread the Allies intended withdrawal route, had bought some time but the shortage of ship transporters meant that 6500 NZ, Australian and British troops would have to be left behind to become POWs – of these, a third (2100) were NZ soldiers. Sgt. Henley coordinated the extraction and care of the walking wounded and sick who would be crammed into the few destroyers that did eventually arrive. Once back in Egypt, Sgt. Henley rejoined the remainder of the Field Ambulance and medical units who had concentrated at No.1 NZ General Hospital in Helwan, a suburb of Greater Cairo about 30km south of the city. Here all medical units set about reconstituting their assets in preparation for the next phase of operations in the Western Desert.

NORTH AFRICA – Western Desert

German infantry and mechanised armour (Rommel’s Afrika Corps) had landed in North Africa in Feb 1941 to assist the Italian Army who had been routed by the British Commonwealth Western Desert Force from their historical territories. Part of the Africa Korps had arrived at Tripoli and during the ensuing nine months had advanced some 1000 miles to the east across the Libyan desert to Cyrenaica taking most of the key coastal towns and Allied strong points as they went, including Tobruk from the Australians. The enemy’s intention was to destroy the Allies by pushing all the way through to Egypt and take Cairo. Tobruk was only 80 miles from the Libyan-Egyptian border.

The broad intention of the British offensive in North Africa was the destruction of enemy forces in North Africa, and the first phase was to be the recapture of Cyrenaica. The relief of Tobruk had at first been incidental to the plans, but now became the major objective of the Allied 8th Army supported by air and naval assets. The 2nd NZ Division was used to achieve it. 20,000 NZ troops, nearly the whole of 2 NZDiv, were preparing to move from Baggush on the Egyptian Mediterranean coast, to the start line, ready to enter the Libyan Desert from the Egyptian side to confront the Afrika Korps head-on and rout their advance.

LIBYA, Operation CRUSADER: 18 Nov – 30 Dec 1941

On 18 November 1941, 2 NZDiv crossed the Libyan frontier into Cyrenaica to take the fight to the Afrika Korps – Operation CRUSADER was underway. Now a Staff Sergeant (S/Sgt.) Jim Henley and 4 (NZ) Field Ambulance joined with the main bodies of 5 and 6 Field Ambulances, the Mobile Surgical Unit, and 4 Field Hygiene Section as they crossed the wire from Egypt into Libya on 21 Nov 1941. As part of the 6th NZ Brigade, the plan was for the Field Ambulances to set up a chain of Advanced Dressing Stations (ADS), with one every 25 miles, sufficiently camouflaged and back Ahe Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) nearer the Libya–Egypt frontier.

As the German Panzers and depleted Italian armoured and infantry units swept across the Libyan desert from the west, the vulnerability of the NZ Brigade’s Ambulance units on the flat desert terrain with little natural protection for the ADS’s and CCS’s became very apparent. A Field Ambulance is attached to each infantry battalion and moves as the battalion moves, setting-up in a protected position whenever the battalion stopped. In the flat terrain of the Libyan desert the threat from shrapnel, miss-directed or ricocheting artillery and tank fire, air attack, and small arms fire posed a real problem for the Ambulance units and Mobile Surgical Unit where there was no above ground protection available. There was also no guarantee a ‘red cross’ would be sufficient to ensure patients and staff protection!

The pressure on the NZDiv to reach its objective, a trig point known as Point 175 about 70 miles SE of Tobruk, was actually just a small cairn of stones on a large flat and elevated plain that featured roughly parallel escarpments, one falling away on the northern side of Point 175 and the other along its south side. Upon learning that the faster moving Afrika Korps was preparing a counter-attack, the vulnerability of Field Ambulances, Field Hospital and Mobile Surgical Unit (MSU) with no affordable protection at Point 175 were ordered to co-locate in a large wadi named Rugbet en Nbeidat that NW-SE and pierced the south side the southern escarpment. The wadi would also provided protection for the NZDiv’s transport assets as well as some 1500 German and Italian POWs who had been captured during the NZDiv’s advance. The POWs were contained in a temporary barbed-wire compound under guard of NZ infantry.

The terrain surrounding Pt 175 and the wadi was flat as a tack as far as the eye could see, featureless sand covered with small rocks apart from the occasional single story mud brick building or mosque. The Nbeidat wadi afford great below-ground level cover from view and protection from line of sight small arms fire. These same advantages were also available to the enemy – it really depended on who could dominate the high ground first. The one thing a wadi did not provide however was protection from air attack, artillery or mortar fire. The urgency to secure these strategic objectives had pressed the NZDiv to continue its westward move through the night of 27 November.

The three Field Ambulances, the MSU and Field Hygiene Section arrived at the wadi and were quickly organised into an integrated field hospital, and none too soon. 15 and 21 Panzer Divisions from General Erwin (“Desert Fox”) Rommel’s Afrika Korps were bearing down on the NZ position from the South West and South East.

About four o’clock on the afternoon of 28 November, the Battle of Sidi Rezegh was initiated by a tank battle that developed about a mile and a half to the south of the wadi. Just on dusk the Nbeidat wadi was unexpectedly attacked from the south-east by 15th Panzer Division. The Panzer’s superior speed and consequent sudden arrival at the wadi took everyone by surprise, especially as they were not accompanied by infantry which was the norm. Nevertheless, the swift capture of the wadi resulted from 21 Panzer Div inflicting significant damage on 5 and 6 Brigades fighting assets. A large number of Allied POWs now replaced the German and Italian POWs in the wadi compound, along with the non-medical personnel that were in the wadi. For S/Sgt. Henley and the medical staff it was business as usual. Their medical treatment services were still very much in demand for both German and Italian casualties, as well as the NZDivs.

“Shellfire Wadi”

About midday on the 30th, the NZ artillery (down their last 60 rounds per gun and awaiting support to arrive from the British Royal Field Artillery) engaged German armour and artillery with deadly accuracy. Some fourteen German artillery gun emplacements had been positioned during the night along the north-eastern rim of the wadi, the closest being no more than 150 meters from the dressing station’s Red Cross flag, and immediately above the Mobile Surgical Unit’s tents. Thirty enemy tanks had also been drawn up on an elevated southern ridge of the.

Fortunately the British field artillery fire arrived to sustain the shelling of the German positions. Although their shooting was very accurate, a number of shells fell short into the hospital area and caused casualties. In the dressing station, the constant scream and burst of exploding shells, and the whine of shrapnel around and through the tents was terrifying for the patients and medical staff. One shell fell into a Mobile Dressing Station tent, killing a patient and wounding three others, while a direct hit on one of the Mobile Surgical Unit’s tents killed an orderly and five patients. In 4 Field Ambulance’s tent lines the shelling had caused more casualties among medical staff and patients. Somewhat less concern was shown by the Kiwis when a tent of Italian patients took a direct hit killing all occupants. By the end of the day the wadi had well and truly earned its new name … it was dubbed “Shellfire Wadi.”

The accuracy of the Allies shelling of the Panzers and German artillery during the night had taken its toll, to the extent that under the cover of darkness the Panzers quickly and as quietly as possible withdrew from their positions around “Shellfire Wadi” and disappeared in the early hours of 31 May. The Germans had handed over responsibility to their Italian allies, to continue the fight and for the wadi’s occupants. The Italians back-filled the German artillery and tank positions with their own.

Allied artillery and mortar fire re-commenced at sunrise on the 31st at what was assumed were still German occupied positions around the wadi. It did not take long for the NZ and British units to work out from the lack of accuracy, their targets were Italian. The shelling continued until late morning and wrecked havoc among the Italians resulting in a decision to quit the position. Not long after the shelling ceased Italian trucks arrived in the wadi to evacuate all German and Italian walking wounded from the Hospital. The Italian artillery and remnants of their armoured units remained in place along with a skelton force of soldiers to guard the remaining Allied personnel, medical staff and patients. Critically injured and ill Italian patients were left in the care of the medical staff.

Once the convoy was out of sight all Allied personnel remaining in the wadi were paraded. The Italian combat officers came down from their tanks and artillery positions around the wadi rim, and started to systematically loot the entire position. Bivvies and tents, personal packs were ransacked, rations and water and anything portable or of use was taken. Pockets were emptied and all personal possession of value were taken, with the exception of wrist watches. The demand to hand these over was met with very stiff verbal resistance, and so were left.

S/Sgt. Henley being a very correct and ethical man did what he could to hinder theses Geneva Convention violations being perpetrated upon the medical staff and patients. He was a man who placed great store in personal example but his protestations fell on deaf ears. However he was not about to let the Field Hospital’s Red Cross flag fall to enemy hands. Fortunately the looting officers had not taken the flag which was flying atop the Field Hospital and so he surreptitiously lowered it and concealed the flag by wrapping it around his waist under his shirt and securing it in place.

Leading by example

POW selection

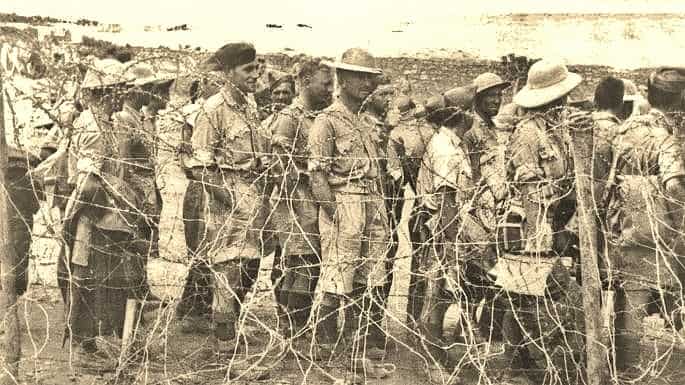

During the afternoon of 31 May all ranks and the medical staff not engaged in the immediate care of patients, were again paraded by the Italian Officer in Command, this time for the purpose of POW selection. All non-medical personnel plus the NZMC ranking officers, warrant officers and SNCOs were selected first. The Italians showed a small degree of favour toward the medical staff caring for the seriously ill German and Italian patients – they were permitted to stay. In total, approximately 860 patients and medical staff remained in the wadi.

Fourteen Medical Officers and 182 other ranks (including S/Sgt. Henley) were loaded into trucks on 01 December and driven away to POW camps at Benghazi (the capital of Cyrenaica) and Derna, further east along the Mediterranean coast. Sadly some of those on the trucks were killed or wounded during the journey back toward the coast, the result of opportunist Allied aircraft bombing or strafing the “Italian” convoy.

The POW compound at Derna was already holding many thousands of Allied prisoners. As soon as he arrived, S/Sgt. Henley was already hatching a plan of escape. All soldiers are taught that it is their duty to make every effort to, and to do it as early in their captivity as possible while they are still relatively fit, fed and healthy. The coastal POW compounds were only temporary holding facilities that were used pending the arrival of cargo ships which would transport prisoners to the more permanent camps in Italy and Germany (officers and senior NCOs generally went to the German camps).

The lax security of these compounds by their Italian ‘hosts’ (fostered by a burgeoning trade in cigarettes with the POWs) afforded Jim Henley an opportunity after dark to gain access to a vehicle and disable it by removing the rotor arm from the distributor. This was to be his getaway vehicle once he got the thumbs up from the senior ranking POW officer to make his escape attempt.

Meanwhile, the medical staff back at “Shellfire Wadi” continued to professionally perform their duty of care for the remaining patients as best they could, under the ever watchful eyes of their Italian guards. The threat of renewed shelling by Allied artillery remained ever present, but … the guns remained silent for the first few days of December 1941. For those in the wadi (Italians included) their personal situation was becoming grave for another reason – food and water supplies that had not been looted were in very short supply. The Italian Commander had assured the Senior Medical Officer (SMO) that a re-supply was imminent but by 5 December the re-supply of food and water had not materialised. After the evening meal (such as it was!) the SMO informed the Italian Commander the food was exhausted and there were just 30 gallons of water remaining for the 860 patients, medical staff and the Italians themselves.

Patients and staff alike were starting to suffer with swollen tongues and acute hunger. The Italian Commander, realising the seriousness of the situation (most for themselves), decided to move everyone out of “Shellfire Wadi” as soon as he could muster enough trucks to move everyone. To make matters worse the Allied shelling had re-commenced at night and the Italian gun-crews were being run ragged changing their fire positions to avoid being accurately ‘ranged’. They were showing the signs of strain. An absence of food, severely rationed water supply, and suffering from sleep deprivation courtesy of the shelling, tempers were frayed to breaking point. Soldiers openly argued with their superiors and fought among themselves – indiscipline was in free-fall.

Resistance and release

When the nightly NZDiv artillery bombardment commenced on the evening of 5 Dec, the medical staff had jointly decide to show their complete indifference to their captors by treating it as any other night, going about their business calmly and methodically, ignoring them and the near misses. The artillery and mortar fire focused on the Italian positions around the top of “Shellfire Wadi” was accurate causing the gun-crews to scramble throughout the night to re-position the guns. This provided an inadvertent sideshow and a great source of amusement to the medical staff. They taunted and jeered the gun-crews, whistled and shouted every time a gun-crew went into scurry/panic mode to move their position.

By sunrise on the morning of 6 Dec it was clear the Italian captors had had enough – they had ‘abandoned ship’ after the nightly barrage ceased and vanished into the night. Not a single Italian soldier remained. “Shellfire Wadi” had been surrendered and by default and back in the hands of its NZ occupants. Transport was requested for the 510 patients plus the 210 medical staff that remained in the wadi. Together with the 5 and 6 Brigade units that had become separated during the night, the convoy set off in the afternoon headed north-east to the British and South African medical facilities that were located near the Libya–Egypt border.

The convoy however was not completely ‘out of the woods.’ The journey back to the border was subjected to random strafing by Ju 87 Stuka aircraft, always preceded by predictable but nerve-rattling sound of the wailing Jericho-Trompete (Jericho Trumpet) sirens fitted to their undercarriage legs. These random attacks had caused additional casualties before the convoy finally reached the relative safety of the Tobruk Garrison at Ed Duda.

S/Sgt. Henley did not get the opportunity to put his escape plan into action. As the Allies tightened their grip on the ground around Tobruk, the security regimes imposed by their captors ramped up. Tobruk was re-taken by the Allies on 22 Jan 1942 and Rommel’s battered Afrika Korps was beaten back along the Lybian and Tunis coastlines into the western desert. Derna and Benghazi were taken on 7-9 Feb thus freeing S/Sgt. Henley and the interned medical staff held in temporary POW compounds. The medical staff were then repatriated to Baggush in Egypt.

Training Depot needed

On 13 June 1942 S/Sgt. Henley departed Egypt from Alexandria on one of 14 troopships that convoyed troops and patients back to NZ. He had been identified as suitable for commissioning and so was returning to NZ to undertake formal officer training. There was also an ulterior motive for commissioning Jim Henley.

An urgent need had been identified by the Army Director of Medical Services for a permanently staffed medical training facility to train NZMC officers and other ranks reinforcements before deploying them to North Africa (and later Italy and the Pacific). At the time there was only one qualified officer instructor which clearly was insufficient to train the quantity of reinforcement personnel required. To have training staff of S/Sgt. Henley’s calibre who was not only medically qualified, but also an experienced instructor with first hand combat medical experience, was the ideal and would be invaluable for the development and oversight of a training syllabus for the new unit. Once commissioned, it was proposed Jim Henley would take a key position on the MC Training Depot staff.

A majority of 2NZEF medical reinforcement personnel were drawn from the Territorial Force units, most of these part-time soldiers lacking in the skills necessary for operating in a desert theatre of war. The plan was to have selected NZMC instructors trained and sent to these units to prepare future reinforcement personnel for attendance at a 10 week pre-embarkation combat medical training course that would be run at the proposed Medical Corps Training Depot at Trentham. Preparatory training would also assist in reducing the planned ten weeks training to three weeks in order to speed up the availability of replacements overseas. After some delay, Army HQ finally authorised the establishment of the Training Depot at Trentham with a complete establishment of administrative staff and instructors.

‘Courage under fire’ begets ‘Knife and Fork’ course

After a brief period of leave at home in Auckland, Officer Cadet Henley returned to Trentham to attended a seven week officers’ commissioning course, disparagingly referred by soldiers commissioned from the ranks as a “Knife & Fork” course (as in, being taught how to use a knife and fork like an officer!). Jim Henley was duly commissioned in the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, NZ Army Medical Corps on 21 August 1942.

Shortly thereafter, 2Lt. Henley’s award for gallantry, the Distinguished Conduct Medal, was officially announced and promulgated in the London Gazette on 09 September 1942. While permitted to wear the medal ribbon on his uniform, Jim would not receive the medal until June 1944. This was due to a manufacturing backlog caused by the huge numbers of campaign medals being produced, as well as gallantry and meritorious service awards. The UK was responsible for the manufacture and distribution of all imperial campaign, meritorious service and gallantry medals, for the participating Commonwealth countries. In addition the gallantry medals had to be officially impressed with the soldier’s name and military details before distribution, thereby exacerbating the delay.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

NEW ZEALAND HERALD, 6 JUNE 1944

PUBLIC INVESTITURE TOWN HALL CEREMONY

A woman missionary and 64 officers and other ranks of the Navy, Army, Air Force and Merchant Navy who have been decorated for gallant or distinguished service received their awards at a public investiture held by the Governor-General, Sir Cyril Newall, yesterday. Because of the wet weather, arrangements for having the ceremony in the Outer Domain were cancelled and it took place in the Town Hall. About 2000 official guests and members of the public attended. The official guests included next-of-kin of those receiving awards and representatives of the services, among them American officers, and of various civilian bodies and organisations.

Scene in Town Hall.

The Governor-General was accompanied by Lady Newall and was attended by Major-General P. H. Bell, C.B., D.S.O., A.D.C. to His Majesty the King, Commodore W. K. D. Dowding, D.S.C., R.N., Brigadier A. F. Conway, O.B.E., Air Commodore S. Wallingford, C.B.E., and Lieutenant-Colonel A. J. Coutts, all honorary aides-de-camp to His Excellency. Major H. A. Jaffray, Military Secretary, read the royal warrants and, in some cases, the citations accompanying the awards. Flight-Lieutenant H. A. Eaton, A.D.C., assisted the recipients. A large area was cleared on the floor of the Town Hall and those who were to be invested were drawn up at one side of this space in three ranks. As their names were called they marched individually to the centre of the hall and then to the stage. Here, Brigadier Conway took the appropriate award from a table and placed it on a cushion carried by Commodore Dowding. The Governor-General then received the award and presented it. After that ceremony both he and Lady Newall shook hands with the recipient. The solemn ceremonial, the formal phrases of the King’s commands, and the stories of gallantry which were told in the citations that were read combined to make the investiture peculiarly impressive. A woman missionary, an Army nurse, doctors, a chaplain to the forces, airmen who have fought against the enemy in the Pacific and in Huropo — including one who sank a Japanese submarine, sailors who helped to sink another submarine off Guadalcanal, and soldiers who have served in almost all the Second Division’s many battles, were among those who received a variety of awards. They were as follows: —

List of Awards.

….; Distinguished Conduct Medal (D.C.M.). — Lieutenant J. C. Henley, of Auckland; Second-Lieutenant C. W. Carter, of Taumarunui; Second-Lieutenant Rihimona Davis, of Kawakawa; Second-Lieutenant S. V. Lord, of Frankton; Warrant-Officer (Class II.) A. Fletcher, of Whangarei; Sergeant R. J. Moore, of Tatuanui, Morrinsville; Sergeant J. T. Donovan, of Remuera; Private J. A. Snell, of Ponsonby; Private S. Yates, of Kaitaia. …..

** The Citation for Lt. Henley’s award reads:

Citation for the Distinguished Conduct Medal

7095 Staff Sergeant James Cyril Henley – 4th Field Ambulance, NZMC—2NZEF

This non-commissioned officer while under fire showed great courage at NBEIDAT, Libya. On the afternoon of 30 November 1941 the 4 NZ Field Ambulance dressing station came under continuous shell-fire over a period of several hours, during which both patients and orderlies were killed and wounded. Staff Sergeant Henley displayed a complete disregard for his own safety during this period and continued is task of organising the reception and evacuation of patients from the theatre. He materially assisted in the care of the injured and by his personal example encouraged confidence in his men. A particularly high standard of work was maintained throughout the whole operation by Staff Sergeant Henley, who by his own contempt for danger inspired everyone with whom he came in contact.

Supplement to London Gazette: 9th September 1942

Duty Calls … Marriage

Ten days after his Distinguished Conduct Medal was announced Jim Henley was married to Eva Marjorie BELL of Auckland on 19 September at the Pitt Street Methodist Church in Newton, Auckland. Officers and members of the 1st Auckland Regiment and the St. John Ambulance Brigade provide a guard of honour outside the church for the newly-weds.

2Lt. Henley had little time to sit back and take in his new found status as a husband as ‘duty called’ at Trentham. The NZ Training Depot having been authorised needed to be organised, the training plan devised, equipment acquired and training started. His training role at the NZMCTD continued through to the end of the war and a little beyond during which time he was also promoted to Lieutenant. It was Nov 1947** when Lt Henley was finally transferred back to the Territorial Force and the Auckland Regiment until 1950 when further transferred to the Reserve of Officers List. This in essence obligated Jim to return to full-time service if required within a specified period of years. Beyond that, now Captain Henley continued in his capacity as a Territorial RNZAMC officer until he reached the mandatory retiring age of 50 in 1963.

7095 Captain James C. Henley, DCM, ED* RNZAMC was placed on the NZ Army’s Retired List of Officers on 21 July 1963.

Note: ** the NZAMC received a Royal Warrant in 1947 thus becoming the RNZAMC

Awards: Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), 1939-45 Star, Africa Star, War Medal 1939-45, NZ War Service Medal, TF Efficiency Decoration & Bar (ED*), TF Efficiency Medal, Service Medal of the Order of St John, Greek War Medal (Crete)

Other: The NZ Defence Service Medal was instituted in 2011 and recognises actual or accumulated NZ military service totalling a minimum of three years, from 1946. Ribbon clasps denote the type of service undertaken (Regular, Territorial, National Service, CMT). Captain (Ret’d) J. C. Henley received the NZ Defence Service Medal with Clasps: REGULAR and TERRITORIAL

2NZEF Service Overseas: 4 Jan 1940 – 12 Jun 1942

TF & Home Service: 15th North Auckland Regiment Cadet Battalion; 1st Field Ambulance, NZ Medical Corps (NZMC); The Auckland (Infantry) Regiment – 1st Field Ambulance, NZ Army Medical Corps (NZAMC), later RNZAMC

Total NZ Army Service: 1932 – 1963 = 31 years

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The post-war years

Once Jim had been transferred to the Reserve of Officers he knew that as much as he enjoyed serving in the Army, his days remaining in the Territorial Force were numbered. The following year, 1951, Jim at the age of 48 also decided his milk-vending days were done and took the bold step of becoming a school teacher. Jim attended the Auckland Teacher’s Training College in 1952-53 and Auckland University 1953-54, before he was appointed to a Primary teaching position at Meadowbank School in Remuera. A post teaching General Science at Remuera Intermediate School followed until April 1957 at which time Jim took the opportunity for a lifestyle change and applied for a position with the Education Department’s Country service. His desire and commitment to help others had inspired him to take his teaching skills, St John work and life experiences somewhere he thought he could make the most difference – Jim chose the impoverished and rural East Coast of the North Island.

Ruatoria, Hawkes Bay

Waitakaro is a rural whistle stop about 10 km south of Ruatoria and it was here that Jim took up his first appointment as the Principal of Hiruharama Maori School. After a few years Jim and family moved into the town of Ruatoria when he was appointed the Principal of the Ruatoria School, and later, President of the New Zealand Educational Institute (East Coast Branch).

Jim Henley’s relaxed, non-judgemental and approachable style together with the desire to improve the lives of others around him, made Jim and his family welcome and popular additions to the local East Coast communities. Jim loved the people of the Coast, his job, and the Coast itself – he must have since he and Marjorie stayed for the next 21 years. During his time on the Coast Jim’s dedication to Ruatoria and the wider rural communities allowed him to contribute and achieve much. As an active St John officer, Jim started the Ruatoria St. John Cadet Unit (a youth unit which became part of the Gisborne Division of St John) which gave so many young New Zealanders from the remote areas of the Coast, an opportunity to participate and learn new skills. He gave freely of his medical and life saving skills and his extensive training experience, qualifying many young people to all levels of proficiency. His personal interest in the Coast’s environment was evidenced by his voluntary appointment to the Dept. of Conservation as a Wild Life Officer; he was an Honorary Fisheries Officer, the Inspector of Scenic Reserves on the Coast, a Member of Forest and Bird, and the Regional Representative (Gisborne) of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (more commonly known as ‘Birds New Zealand’). Jim Henley had even designed and established a program for researching and mapping the bird life on the East Coast.

Jim Henley’s military and St. John service had instilled in him a deep sense of loyalty and commitment. A loyal supporter of the Ruatoria RSA he became Secretary-Treasurer for a number of years, and was a staunch advocate for returned veteran’s welfare. As a St. John officer and returned veteran, Jim was instrumental in having the war service of any St. John members who had served overseas with 2NZEF recognized as qualifying service towards the award of the Service Medal of St John.

Jim never wasted a minute. He was always looking to another project or something by which he could bring benefit to those around him. During the 1960s Jim and a few friends built a batch for the Henley family at Piha (quite a hike from Waitakaro and Ruatoria!). Ever the environmentalist, while there Jim started collecting various varieties of butterflies but only those that regularly blew in from across the Tasman. Piha as most New Zealanders know is renowned as one of the premier surfing and life saving competition capitals of New Zealand and it was here that Jim was inspired to capitalise on and expand his St. John experience. He set about qualifying as a Royal New Zealand Life Saving Society instructor and examiner. Jim then started teaching and examining as many young surf lifesavers as his time permitted.

Order of St John

The Order of St John in New Zealand had grown markedly during the Second World War from its tentative beginnings in Christchurch in 1885. The St. John Ambulance Brigade became firmly established in New Zealand as an official Branch of the Order in England. In 1946 the NZ Brigade was recognized as having ‘come of age’ and was elevated to a full Priory, the NZ Priory of the Order of St. John, with the Governor-General of New Zealand as the Prior.

Having joined the St. John Ambulance Brigade as a Cadet at primary school, Jim Henley was considered to be one of the founding members of the Priory in New Zealand. He had became a qualified Instructor and Examiner at all levels of proficiency and had progressed through the non-commissioned ranks of St. John, to be commissioned and eventually attained the rank of Divisional Officer, Grade II (a Lt. Col equivalent). An undying enthusiasm for the organization, the work and its members gave Jim the opportunity to train and mentor hundreds of St. John members at all levels of proficiency and management.

Recognition of Service

The Service Medal of the Order of St John is unique as it is the only medal still issued that retains the image of Queen Victoria and the only one which has her facing to the right (dexter). It was first awarded in New Zealand in 1908. Jim was awarded the Service Medal of the Order of St John in 1947 for the completion of his first 15 years of efficient service (this period was reduced internationally to 12 years in 1990). While Jim’s service had transitioned the implementation of the 15 year to 12 year qualifying criteria, a review of his service made no difference to the total years served as he had qualified at the 15 year point which occurred well before this change was bought into effect.

After 15/12 years, a SILVER Bar was added to the medal ribbon for each successive five years of service [maximum of 5 Bars = 25 years] – Jim had all five. At the 40 year point, all silver bars were replaced with a GOLD Bar representing additional five year periods of service (max of 5 = 25 years) – Jim had all five. Thereafter all Bars were removed after 52 years of service and a Gilt Laurel Wreath alone worn on the medal ribbon – Jim, not quite! The GOLD Bar system was retired in 2004 and replaced with a single Gilt Laurel Leaf awarded at the 52 year service mark.

Jim’s contribution to, and on behalf of, the Order of St. John in New Zealand gained HM the Queen Elizabeth II’s royal acknowledgement in 1961 when he was made a Serving Brother of the Most Venerable Order of St. John (SBStJ). Jim’s continued devotion to service and leadership received Her Majesty’s subsequent approval for a further accolade within the Venerable Order – he was promoted to the grade of Officer of the Most Venerable Order of St. John (OStJ) in 1964.

By the time Jim Henley retired from active duty with the Order of St John, he had given a very laudable 65+ years of service (including his WW2 qualifying service which Jim had championed and is now a permanent regulation). This milestone was reached on Jim’s 77th birthday in 1991 and whilst retired from active duty, Jim’s membership of the Order remained continuous until his death.

Gisborne

Jim and Marjorie Henley eventually left their coastal lifestyle in Ruatoria behind in the early 1970s, retiring to make a new home at 9 Mason Street in Gisborne. From here Jim could maintained his connections and commitments to the various organizational he had memberships with, but without the significant travel he used to undertake from Ruatoria. Sadly, Marjorie Henley unexpectedly passed away at their home on 23 September 1976, aged 65. Jim remained at Mason Street for the next 20 odd years, keeping as busy as his advancing years and energy allowed.

Royal Acclaimation

Jim Henley’s lifetime commitment of service to the organisations and communities he lived were recognized at various times with awards of appreciation and thanks. Jim’s extensive lifetime contribution of community service was officially recognised and rewarded by a third accolade endorsed by H.M. the Queen Elizabeth II.

James Cyril Henley OStJ, DCM, ED* was invested as a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (Civil) by the Governor General of New Zealand at Government House, Wellington in 1988.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

7095 Captain (Ret’d) RNZAMC / DO Grade II (St. John) James Cyril Henley MBE (Civ), OStJ, DCM, ED & Bar died on the 8th of April, 1994 at the Gisborne Hospital aged 80. Jim Henley’s ashes were buried with his wife Marjorie’s in the Taruheru Cemetery, Gisborne.

Era i roto it e rangimarie Rangatira ..

Jim Henley’s medals as worn:

Medals of 7095 Captain (Ret’d) James Cyril Henley MBE (Civ), OStJ, DCM, ED* – RNZAMC

Left to right: MBE (Civ), OStJ, DCM, ED*, 1939-45 Star, Africa Star, War Medal 1939-45, NZ War Service Medal, Efficiency Decoration + Bar (TF), Efficiency Medal (TF), NZ Defence Service Medal with Clasps: REGULAR and TERRITORIAL; Service Medal of the Order of St John ***** (g), Greek War Medal 1940-41

* = denotes a bar for subsequent periods of service

* (g) = denotes GOLD service bars

Taonga goes home

What M. did not know when we last initially spoke at the beginning of her inquiry was I vaguely recalled seeing Jim Henley’s medals on-line, albeit a year or more before. Because of the elapsed time I could not recall the who or where, but rather that the medal group being unique I imagined the seller would likely fetch a good price for them. A highly ranked combat gallantry medal and Royal honours is a very attractive combination to specialist collectors.

Whenever unusual or historically significant NZ medals appear on-line I am apt to keep a picture for future use as ‘window’dressing’ on the MRNZ website. My concern with these medals was that irrespective of whether I had kept a picture or not, because of the elapsed time (a year+?) I surmised they would be long gone, probably overseas, and therefore would be irrecoverable. I told M. if the medals were in NZ, and IF they could be found, and IF the owner was prepared to re-sell them, they would not do so without wanting to make a profit. M.’s response … “It doesn’t matter what it costs – somehow I will find a way, I’ll sell the house if I have to get those medals back.” I re-assured M. that I did not think she would need to go that far (I hope). M. was adamant. If at all humanly possible, she (the family) would do whatever it took to get their father’s medals back. I mentioned the note I had found on Jim Henley’s Cenotaph page from “John” and M. confirmed it was a nephew.

As luck would have it had kept a picture of the Henley medals and added some relevant detail at the time. From this I was able to determine whom I needed to approach to find out the the fate of the medals. I discovered they had not left the country but had been sold and in the hands of a private owner/collector. That meant as long at the medals were in New Zealand there was always a remote chance they could be recovered and so I advised M. of my progress. I left M. in no doubt that in order to recover a group of medals such as her father’s, any owner would be unlikely to hand them over on request. If legally purchased, a family has no automatic right or entitlement to ownership of any item previously owned by their family, irrespective of the circumstances of the loss. The only possible exception could be if the loss occurred as a result of theft or burglary.

My next call was to John Henley, the author of the message on the Cenotaph file. John is a former soldier and the eldest grandson of Jim Henley. When I made contact with him and explained the situation, and that M. had wanted him, John, to act on the family’s behalf to try and get the medals back I suggested it may be better if I acted for them and liaised re progress, as there were many pitfalls in the negotiation process. Inexperience in the world of military medals and medal negotiation could un-necessarily cost a family dearly for a nil return. John and M. were more than happy to step back and for me to act on their behalf and see what, if anything, could be negotiated.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The process of tracing the medals, determining the possibility of a re-sale, and the subsequent negotiations took roughly a month to finalise. Fortunately the collection was intact as sold, but only a few days from a potential international sale. A last minute delay in finalising the Ministerial authority was sufficient to buy some time and put a proposal to the family.

Jim Henley’s medals and the suitcase of ephemera have since been delivered to John who admitted it was a very emotional moment to see his grandfather’s medals again, to hold them in his hands and to see the photograph of his grandfather wearing the medals. As a former soldier John knows only too well the significance and emotion medals have servicemen and veterans. The extrinsic value of his grandfather’s medals and the associated ephemera can be measured in dollars, but compared to their intrinsic value, the pride, the mana and emotion these taonga evoke in the Henley family is incalculable.

John and M. could not have been more relieved and thrilled to finally have the medals and memorabilia back in family ownership. As Jim Henley’s eldest grandson, John is now the family’s designated kaitiaki (caretaker or guardian) of his grandfather’s medals and memorabilia, and to that end, John has made arrangements to ensure they will never again leave the family.

John and Awhina Henley’s daughter Hiria is their first born, destined to become the caretaker of her great-grandfather’s medals for her generation. Hiria has already had her first lesson as a ‘kaitiaki in training’ having attended her first Anzac Day this year in Gisborne at the tender age of 4 months.

Te taonga me te tiaki i o taonga Kaitiaki Hōne – pai te mahi Whānau !

The reunited medal tally is now 230.