16/570A ~ JAMES CLUNE

A medal found by Shane Bocock of Balclutha in his late father’s belongings, was impressed in the name of soldier, 16/570A PTE. J. CLUNE N.Z.E.F. Shane’s father, the late Murray Bocock from Taranaki, had completed his Compulsory Military Training in the late 1950s and Shane reckons given his interest in all things military, would have enjoyed a career in the Army however it was not to be. As they say life got in the way and instead Murray became a joiner and builder. The family at some point moved to Te Awamutu where Murray joined the local RSA and maintained a life-long interest in its activities. It was his interest in militaria that united Murray and the WW1 Victory Medal named to James Clune. Shane has no idea who James Clune was, or how his father came by the medal and so decided to try and get it returned to the Clune family – as a result he contacted MRNZ.

I wonder if Murray Bocock new the background of the person the medal had belonged to? In fact at one point in his life unbeknown to Murray, he had lived in close proximity to James Clune who had spent a lengthy period of time in Cambridge.

The NZ (Maori) Pioneer Battalion

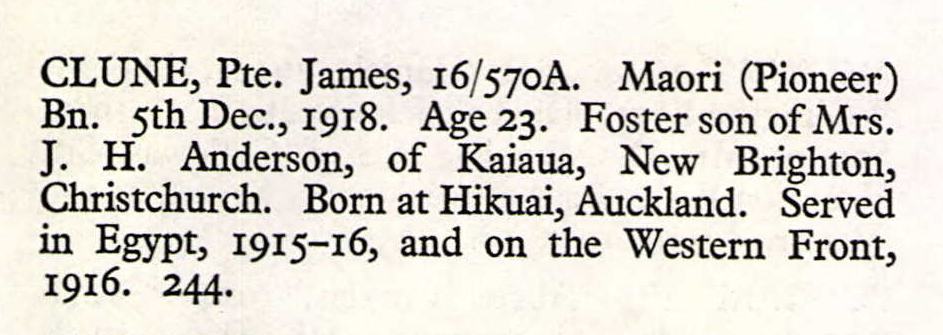

Private James Clune was a member of the New Zealand Pioneer (Maori) Battalion, a unit whose history throughout the First and Second World Wars, man for man, was arguably without equal.

The Pioneers were not front-line fighting units but a military labour force trained and organised to work on engineering duties, digging trenches, building roads and railways, and taking on any other logistical tasks deemed necessary. This was essential and dangerous work that was often carried out under fire.

The Pioneer Battalion was organised into four companies, each with two Maori and two Pakeha platoons, the latter formed from the remnants of the Otago Mounted Rifles. Other Maori soldiers were encouraged to transfer to the New Zealand Pioneer Battalion, but many chose to stay in the battalions in which they had enlisted.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Clune challenge …

When I started to look into James Clune’s military file I was immediately struck by his life circumstances as it was not the first time I had researched a medal recipient having come from a similar background, the outcome of which was generally not good – James Clune’s was a familiar story. As I continued to look through his service history I tried to imagined what life had been like for young James before he enlisted, as well as what he must have endured during his time overseas. And of course what of his homecoming, what was he coming home to ? – what did he have to look forward to? – not much at all as it happened!

For James Clune, it could be said of his life that ‘it was over almost before it had started.’

Researching families of mixed race in NZ and particularly from traditional Maori tribal areas like the East Coast or Northland tend to present problems of identification. This is complicated by inter-marriage, frequent movement, and the practice of adopting abandoned, orphaned or illegitimate children (known as whangai) by a whanau within a tribe including extended families. The real difficulty for a researcher without a depth of knowledge of tribal geography and structure, is tracing children whether whangai or not, who have used both their Maori and an Anglicised version of their Maori name during their life (often only in written records such as birth or marriage records), or have used their given English name, e.g. “John Smith”, that has no direct translation into a Maori equivalent. Tracing persons whose names fall into either of these groups can be a nightmare unless the whole family continue to use the same name (be it Maori or English). Add to this the additional difficulty of being able to identify from the outset that a person with an English name, e.g. John Smith, may in fact be Maori but has no apparent identifiable Maori parent – James Clune being a case in point.

James Clune’s first and last names gave no hint he was of Maori descent. The only lead in this direction I had was that he had been a member of the NZ Pioneer (Maori) Battalion during WW1, however I was also aware that not all Pioneers were Maori. This meant I had to work backwards to try and establish exactly who James Clune was, who his family were as all of the indicators in his military file were confusing to say the least, except for the one fact – James had a sister, Daisy Clune (still no indication that the family were of Maori descent). Daisy however became the link from whom I was able to trace her genealogy and ultimately James’s. Sounds confusing I know but as you read on you will understand I hope how convoluted establishing identity is, particularly from NZ’s early days and the random relationships that occurred between white immigrants and Maori.

The only family information I had to start this search with, apart from sister Daisy, was that James Clune had been born at Hikuai (Thames) on 07 February 1895, that his father’s name was also James Clune (in itself a difficulty since differentiation between the two was generally not recorded in early census, like adding Senior or Junior to each). James had also cited two “Mrs Anderson’s” as his Next of Kin in his military record, one being marked “Guardian” and later “Foster-Mother”. In this text I have differentiated father and son accordingly as either James Clune Snr, or James Clune Jnr.

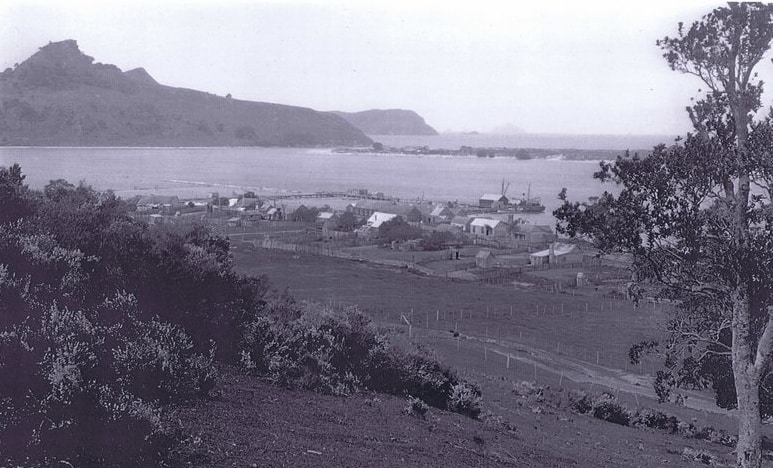

Hikuai, Coromandel Peninsula

To understand James Clune Jnr’s background is to be cognizant of the place and times in which he was born. The Hikuai Settlement is positioned on the E-W Kopu-Hikuai Road along the banks of the Tairua River at the base of the Coromandel Peninsula, on the edge of what is now the Coromandel Forest Park. In 1895 this area fell within the boundary of greater Thames. Hikua is about 10 km inland from the coastal town of Tairua.

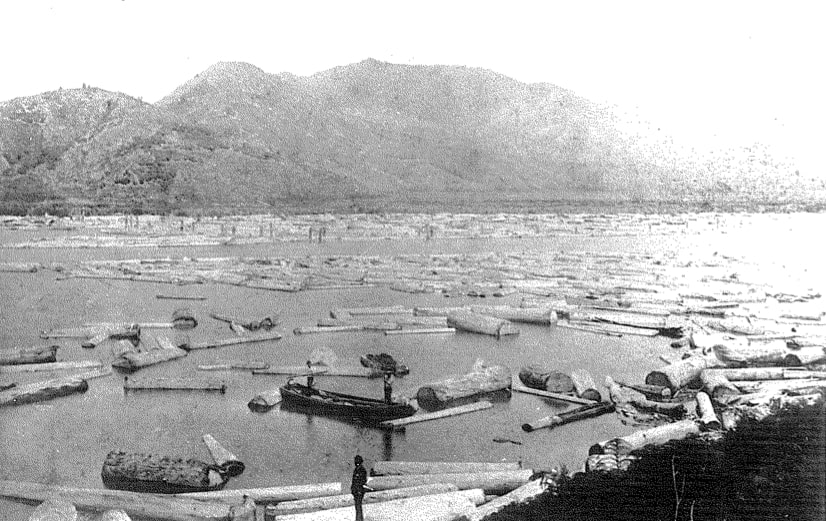

Hikuai was founded on kauri timber, kauri gum and gold. In the early 1820’s several hundred Tainui Maori inhabitants were slaughtered here by Hongi Hika and his warriors, and from that time the Hikuai-Tairua area was never resettled by Maori. The decimated Tainui scattered, many moving north to the Whitianga-Mercury Bay area and other coastal enclaves further north around the Coromandel Peninsula. The opening of the Thames goldfields in 1867 changed that. The immigrant population exploded with many coming from other countries. And come they did, in their thousands – every nationality and background imaginable – royalty to criminal and everything in between. Not only gold miners but also kauri gum miners came as did many labourers and opportunists to support the mining operations. The Coromandel Peninsula was thick with mature kauri trees in untamed bush and labourers were needed to fell the bush, mill the timber and build towns like Waihi and other infrastructure. Hikuai at this time was not even a visible whistle stop on a bush track but just one of the many logging camps on the banks of the Tairua River that sprang up to meet the demands for timber. There was certainly no shortage of work for the Clune men. Whilst work and money became plentiful, for Maori the opportunity to partake in the spoils had drawn many back to the fringes of this area for work, which of course inevitably included females many of whom were employed in domestic duties in the camps, villages and ultimately the towns that grew from the wealth that mining generated.

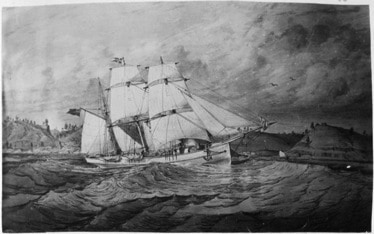

The Tairua River provided the chief means of transport for many years, for boats as well as logs. It was the only way to get them to Tairua for milling. In 1893 gold was discovered at Puketi between the second and third branches of the Tairua River. The claim was called Golden Hills and this discovery brought many more hopeful diggers to Hikuai. In the year that James Clune Jnr was born, 1895, a claim of 100 acres had been pegged out near Hikuai, known as Broken Hills. Boats and paddle steamers regularly travelled from Tairua at the mouth of the river, up-river to Jackson’s Landing at Hikuai to discharge cargo and passengers. Transport to other settlements around the Coromandel Peninsula such as Whitianga was also by boat. Travel to and from Auckland was via steamer either from Thames, or from Kopu at the head of the Firth of Thames.

The local roads in 1903 were described as mud streams. It took five hours for a laden four horse wagon to travel between Hikuai to the Broken Hills mine – about 16 kms. In 1928 a road from Hikuai to Waihi was finally opened for motor traffic but it was not until 1933 that reasonably safe access between Hikuai and Tairua was provided. In 1970 this road was reformed, raised and sealed.

Hikuai was never anything more than a village. In 1878 it had a population of 42. This increased markedly into the thousands for a relatively short period while the gold and gum were extracted, and then just as quickly dwindled, as did the kauri eventually. Today Hikuai consists of a few scattered dwellings, a garage, a school built two years after James was born (current roll 81), and a widely scattered population which in the 2006 Census numbered 3,252 over a very much wider Hikuai electoral and statistical district. Waihi, 40 km to the north, is the nearest town of any substantial size.

The Clune family

The origin of this Clune family is murky. Irishman George Clune (1829-1898) was from County Clare, Ireland and just 20 years of age when he was charged and convicted for larceny (theft) in a Limerick court in March 1849. He was sentenced to be ‘Transported’ to an Australian penal colony for seven years. He arrived on the convict ship Blenheim IV at Port Arthur, Tasmania in Oct 1851. In 1854 he was given a Conditional Pardon (possibly for good behaviour ?) and granted employment by a Mr Oldham of Campbell St., Port Arthur, the same street in which the gaol was built by convict labour in 1821.

George Clune married Margaret REILLY (1821-1895) in April 1854 and together they had a family of sons – Alexander (1856-1929), William (1859-1913), James (1863-1950) and Alfred (1865-?), each of whom was influence by their father’s criminal beginnings. George Clune was not the least bit deterred by his sentence of transportation to Tasmania, continuing to engage in illegal activities (mainly theft and false pretences) which resulted in periods of hard labour and prison time.

Around 1867 George opted for a new beginning. With his wife and young family, George migrated to New Zealand on the Bella Mary, possibly attracted by the prosperity of the young country (various gold strikes had been made around the country) and to escape his past criminal deeds in Tasmania. Once in Auckland George Clune soon reverted to type, quickly becoming a featured client in the pages of the NZ Police Gazette. From 1868 until his death in 1898, crime seemed to be George’s full-time pre-occupation – larceny, robbery, receiving, fraud, using aliases, assault and so on, between periods of incarceration. Sons James and Alfred once in their early teens, had followed closely in their father’s footsteps, no doubt under their father’s guidance and prompting.

Naval Training School – Kohimaramara

Youngest son Alfred Clune had embarked on his criminal career at the tender age of 10 by continually absconding each time his father was sentenced to a period in gaol. As a result, in Oct 1876 the magistrate ordered that Alfred was to be sent to the Naval Training School (NTS) at Kohimarama for a period of three years. It was a ‘sentence’ in all but name and designed to discipline young boys in an effort to prevent them descending into a life of crime.

In 1874 the Naval Training Schools Act was passed in New Zealand. When the Commissioner of Customs, William Reynolds, introduced the Naval Training Schools Bill to parliament, he stated that the prime purpose of institutions established under the legislation was vocational—to provide boys with ‘a thorough training in seamanship.’ The schools were also to serve a social control function in the young colony. Because poverty, destitution, sickness and premature death were not uncommon, children were often left homeless, reliant on community based charitable aid, casual neighbourhood support, or on their own devices. This generated public anxiety as juvenile crime, larrikinism and delinquency became increasingly linked with conditions of hardship and with lack of parental support and control. One solution had been to remove from society children who were perceived to be problems, as well as those considered vulnerable to corruption. To this end state industrial schools had been established with the 1867 Neglected and Criminal Children Act. Reynolds suggested that the proposed Naval schools would serve a similar function. The Naval Training Schools Bill, he explained, was ‘to establish industrial schools for neglected and in some cases criminal children’ so they could be trained for a future in the maritime service.

Without intervention, the neglected boy was seen as a potential pauper or criminal and a future economic burden on the state. Young people who would otherwise become ‘idle reprobates and a charge upon the colony through the gaols and police would be transformed into useful members of society by being trained for a future in the maritime service. Accordingly, the Naval Training Schools Act (1874) identified potential students as ten to fourteen year-old sons of prison inmates, those found begging, homeless, destitute, orphaned or in the company of thieves, those in trouble with the law, and boys whose parents or guardians elected to have them placed in the school, either because they could not control them, or because they could not afford to support them. Such parental requests would not be considered favourably if the child had been convicted of a felony or had served a period of imprisonment.

Modes of punishment included black listing (involving an extra share of unpleasant ‘dirty work’ and denial of recreation time), time in the cells (with or without bread and water), the wearing of a placard on the boy’s back stating the nature of his offence, and caning by the manager. Under the Act, boys could also be tied up to receive up to 20 strokes of the whip, as awarded by the magistrate, and a gaol could be established on the premises.

Citation: Stephenson, M. Kohimaramara Naval Training School. Dictionary of Educational History in Australia and New Zealand (DEHANZ), 7 November 2013.

The Kohimarama Naval Training School was the first and only school to be established in 1876. After seven years and a lack of numbers, the rate of boys absconding, and a work and discipline regime which tended to dominate the lives of the boys rather than learning the skills of seamanship, led to an inquiry which ultimately resulted in the school being closed in 1882. Only the Industrial Schools remained.

Alfred Clune had the benefit of being one of the first boys placed in the Naval School when it opened in 1876 and completed three full years there. He had been ‘selected’ by the Courts because of his father’s criminal activities and record. In March 1878 Alfred (13) was transferred to the SS Wanaka as an apprenticed sailor but after one voyage south, absconded! He was arrested in Hamilton sometime later and charged in the Magistrates Court for breaching the Merchant Shipping Act. Alfred was remanded to the Auckland Magistrates Court on a charge of ‘Desertion’ from the Union Steam Ship Company’s vessel. George Clune pleaded for his son’s release from his indentured apprenticeship and the the Judge eventually agreed. The price for Alfred however was one month in prison with hard labour for his offence! Hereafter, Alfred Clune’s criminal undertakings in Auckland ramped up and appeared to become his life’s work. As far as Alfred was concerned, his path was pre-destined as he was still making court appearances for theft, fighting, drunkenness and false pretences as late as 1923 at the age of 60!

The Clunes and crime : inseparable

In 1886 James Clune had been working in Northland and had met and married Ephra “Effie” Theresa LATHROPE (1864-1941), born in The Strand, London. Effie had emigrated to NZ with her parents and sister. The Clunes had two children – John Leonard Clune (1891-1949) and Andrew John Clune (1893-1940). But unfortunately once James had returned to Auckland with Effie, he re-commenced his criminal activities. In the late 1880s, James became involved in a jewellery robbery which eventually led him to prison and ultimately the end of his marriage to Effie.

The Clune family had gained a good deal of unwelcome notoriety in Auckland for their crimes, the local newspapers giving two incidents a great deal of continuing attention which lasted for several weeks. The first event involved Larceny for which father George Clune was well qualified. George perpetrated a criminal act that drew in both James and Alfred, resulting in all three being arrested and summonsed to appear in the Auckland Magistrates Court.

On a day in April 1887, George Clune had came upon a crashed handsome cab which had turned on its side and was partially smashed near the Bank of New Zealand in Queen Street. The horses had apparently bolted up Queen Street as the cab left the wharf with its singular female passenger on board. The driver, unable to control the horses, was thrown from the cab as it crashed and was knocked out cold. While the woman passenger’s injuries were being attended to by a passerby, George Clune being in the vicinity, had helped himself to a portmanteau from the scattered luggage at the scene and made off. He later discovered it contained a small leather bag which contained the passenger’s personal jewellery (brooches, earrings etc) valued at 250 Pounds ($500), a substantial amount in 1887 which in 2018 equates to a little over $12,000.00.

In the wake of this theft, George Clune (58) had conned both Alfred (22) and James (33) with a story that he had found the jewellery. He then talked them into trying to sell or pawn some of it. This was their undoing as the pawn broker had recognised some of the jewellery as the stolen pieces, from descriptions circulated by the Police. George was also unaware that he had taken the jewellery from not just anyone – the lady in question happened to be none other than Mrs Katherine E. Anson, the wife of the Agent-General for Immigration for the islands of Fiji, who was visiting Auckland. This of course made the crime even more heinous in the eyes of the Police and the presiding Magistrate.

Arrests followed and ultimately it was a seven year old witness’s evidence that sealed George and his two sons fate. The boy had retrieved the portmanteau which he had seen George carelessly discarded into a hedge, and so took it to the Police. Of course George denied everything and true to form, attempted to implicate his sons Alfred and James as being responsible for the theft – clearly no honour among these thieves. After changing his story several times and implicating himself by using several aliases that witnesses testified he had used, George finally admitted to taking the woman’s bag – the end was nigh for the Clunes. Mrs Anson, who gone back to Fiji in the interim, returned to Auckland to give her evidence. William Clune had also been summonsed as a suspect but was able to clear his name since he was able to prove he was not in Auckland at the time of the theft. Mrs Lathrope, the mother of James’s wife, was also called to give evidence for the prosecution, as was James’s wife Effie. There was no mention of Alexander in proceedings.

A newspaper account of the jewellery theft can be read here: JEWELLERY ROBBERY, April 1887

The net result was – “GUILTY” – George, James and Alfred Clune were each sentenced to three years penal servitude at Her Majesty’s pleasure in the partially completed new Mt Eden prison. By the time George Clune died in 1898, he had had accumulated a total of eight years in prison in both Tasmania and Auckland. James Clune had followed suit with three separate prison terms, all related to theft and false pretences, while his brother Alfred …. well, I lost count.

For Margaret Reilly Clune, the boys mother and George’s wife, relief from her husband and son’s criminal lifestyle only came when she died in 1895, aged 54. When the Clune’s prison terms were completed, Alfred Clune went back to his regular job as a Gum Sorter while continuing his criminal lifestyle in Auckland as if nothing had happened, as did his father George. Meanwhile James’s marriage to Effie** was disintegrating. A further six months in prison for false pretences finally ended their marriage. As a result James and brother William decided to get away from Auckland by taking the steamer to the Coromandel where they returned to gum-digging. Prior to leaving Auckland, James had been served a Maintenance Order to provide weekly financial support for Effie and their two children, but he soon fell foul of the law by not keeping up the payments. Consequently the Police came in pursuit.

The brothers went first to Kuaotunu to link up with their elder brother Alexander and his wife Jane who were running a butchery business. Kuaotunu is a village on the eastern side of the Coromandel Peninsula, due east of Coromandel itself. Alexander Clune had originally married a fellow Australian immigrant named Margaret HAY from Thames in 1895, however unfortunately she died the same year. He re-married two years later, Jane Coom PERRY (1875-1954) from Naramine, NSW who had also immigrated from Australia with her parents.

To provide a timing context for the birth of Daisy and James Clune, it was during these first two years that William and James Clune Snr had worked between Kuaotunu and Tairua on the Coromandel Peninsula. It is (presumed) James fathered both Daisy and James Clune Jnr between 1894 and 1896, to an unknown Maori woman from the Tairua-Hikuai area, with possible connections to the Ngatimaru iwi.

NOTE: ** Effie Clune remained in the house she and James and their two children had shared in Chapel Street, Auckland. with the children. In 1903 Effie re-married, Charles Chenowith GROSE, a building painter who also lived in Chapel Street. Effie out-lived four husbands (inclusive of James), and as Mrs Thomas MURPHY, died at the age of 74 in 1941.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The second incident that allowed me to track this particular Clune family was covered in a number of newspaper reports of an on-going problem the brothers faced which had got them into hot water. After the death of Mrs Margaret Clune, George had become dependent on his sons. Knowing all the angles, he had approached the authorities in Auckland and claimed he was unable to provide for himself, that is, he claimed he was destitute. Twenty years earlier the government had passed the Destitute Persons Act of 1877 which made surviving family responsible for those members no longer able to support themselves. George was able to extract a court Maintenance Order obligating his four sons to pay him 5 shillings (50 cents) per week for his upkeep. In July 1897, three of the brothers appeared in court for failing to provide this support.

NEW ZEALAND HERALD, VOLUME XXXIV, ISSUE 10504, 26 JULY 1897

LAW AND POLICE.

Saturday. [Before Mr. H. W. Brabant, S.M.].., Maintenance Cases. — James, William and Alfred Clune were charged with failing to comply with an order compelling them to pay for the support of their father, George Clune. The case was adjourned till August 7th.

August 7th…. James Clune, William Clune and Alfred Clune were each charged with failing to comply with a maintenance order. A sentence of three months imprisonment was imposed, the warrant to be suspended if the payment of One Pound ($2.00) per week be kept up regularly.

POLICE COURT. AUCKLAND STAR, VOLUME XXVIII, ISSUE 213, 14 SEPTEMBER 1897

THIS DAY.

(Before Mr Wm. Earle, J.P.) Maintenance. — …, and a case against Alexander Clune, charged with failing to support his father, was adjourned till the 18th inst.

The 1897 Census listed William and James Clune Snr as being Gum-diggers of Gumtown, now called Coroglen which is midway between Whitianga and Hikuai. Their distance from Auckland and isolation location however did not absolve them from their Maintenance Order responsibilities – it just made the physical process of getting money to Auckland more difficult.

The “Thames Star” dated 15 Nov 1898 provided further coverage on the Maintenance Order saga. An article that gave a partial record of what was obviously an on-going case, recounted that James had been arrested on a charge of failing to appear in Court after a Summons had been issued in relation to his failing to honour a Maintenance Order for his father George Clune. Sound familiar?

The problem appeared to arise from the Police saying that from the time James Snr had left Auckland, his unpaid maintenance payments had accumulated and that he now owed a total of 25 Pounds to his father. The Police claimed that they had given James’s brother William Clune the Court Summons to pass on to James who at the time had been working quite some distance away at Totara on Table Mountain. William denied receiving the Summons and James of course rightfully denied any knowledge of its existence. He contended that on this basis, he could not possibly be guilty of ‘failing to appear’ at court. Besides, he believed the 4 Pounds he had already paid, plus a subsequent sum of 7 Pounds, had completed his obligation to the Order.

The Police Sgt. had also charged James Snr with “Escaping from Custody” at the time he was “arrested” at Table Mountain. There was some doubt apparently surrounding the legality of James’s arrest as he had given evidence that at no time was he verbally informed by the Sgt. that he was “Under Arrest”. The Magistrate concluded by saying he weighed up the defence under two headings: first he deemed“the evidence was contradictory” (he said/she said), and second, “the proceedings were bad” (i.e. the arrest procedure was flawed) “and therefore, the arrest warrant invalid.”

The whole point of reconstructing these events while not relevant to James Clune Jnr’s story, was to establish I had followed the same/correct family throughout the research since there were a number of unrelated Clune families in Auckland and the Waikato at that time. It was also important to try to pin down who had been James and Daisy’s mother, if at all possible. If not, confirmation of their father would be about as near as I was going to get. From the newspaper articles reference so far, the following facts also seemed to provide/confirm information not previously known thus far:

- The Constable for the above arrest and Maintenance Order prosecution, had said, “Witness (James) had not a Maori wife at Gumtown” (this implied the existence and ethnicity of a ‘wife’ of James (snr), whether lawful or common law, but unfortunately remained un-named. The statement also confirmed that James (jnr) and sister Daisy would most likely be ‘half-caste’ – they were.

- Three questions were asked of James Clune by the Police Sgt: 1) To confirm he had been jailed for three years for theft in 1887; 2) to confirm a sentence for False Pretences in 1891; and 3) to confirm a further 12 months jail for False Pretences in 1891. James first refused to answer, then when he did, said he did not remember! For me this confirmed I was still following the same Clune family. The Magistrate sentenced three of the Clunes to prison for their part in the 1887 jewellery robbery in Auckland.

- Police Sgt. asked James whether he had been sentenced as: “James Clune, alias James Dillon, alias James O’Brien?” – James simply replied “No”, in other words he was indicating he had not falsified his name. In fact George and Alfred Clune were on record as having used aliases before, one example being Margaret Clune’s maiden name of “Reilly” which they had used on more than one occasion. In light of this, there was therefore, no apparent reason for the Police Sgt. to conclude that James Clune also would have used an alias since it was he who was attempting to sell or pawn the jewellery (flawed logic but such were the skills of beat police of the day).

- When asked, James admitted he had been sentenced to six weeks imprisonment in 1891 for disobeying a Maintenance Order, but that the Order for which he was now being charged did not refer to him, but his father James (if correct, this could also have been for his wife “Effie” as Mrs Margaret Clune was still alive).

The conclusions drawn here were that given the locations specified in the Police dialogue in court, when combined with census information, newspaper events and dates in time, it was more than possible that James Clune Snr had been working/living in the Hikuai–Tairua area at the time both James Jnr and Daisy were both conceived, and born; if their father was James Snr, he had had a relationship with a wahine (‘wife’ or companion) of Maori descent, somewhere in the Hikuai–Tairua area between about 1893 and 1897. This information approximated the location and period of time in which James Clune Jnr and most probably Daisy Clune, were most likely to have been born.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fortunately for the Clune brothers, having to provide money for their father George did not last long. Their financial obligation and attendant court appearances evaporated after 69 year old George Clune died in Auckland on 22 March 1898. A measure of their father’s destitution was apparent in an entry listed in the Notices of Deceased Estates, 1880-1895 which published the net worth of “George Clune’s Estate – One Pound.” (NZ$2.00). From the time that George Clune had been transported to Tasmania for his misdeeds in Ireland, he continued his criminal offending once released in Tasmania and after his arrival in Auckland. George Clune had achieved nothing in his life other than father sons who followed his pattern of behaviour, proving he was nothing more than an incorrigible petty thief and a poor excuse for a father and husband.

I could find no mention of Alfred Clune beyond 1923 (his last recorded court appearance). He may have died (not registered?) or returned to Australia although his age (60 at the time) suggested probably not. The 1900 NZ Census put Alexander Clune and wife Jane Coom Clune still at Kuaotunu with their son, Alexander (Alex) Clune Jnr who had been born in 1897. Alexander Snr (77) died at Kuaotunu in 1929, and his wife Jane Coom Clune in 1954, aged 79.

The next Census reference for the Clune brothers was 1905, for William and James Clune Snr which showed them both working temporarily in Northland, one gum-digging and the other, a bushman. By 1911 both brothers had returned to Gumtown (Coroglen). William Clune, a bachelor, died at Whitianga in Sep 1913, aged 54 years.

The New Zealand Herald dated 9 February 1914 published a list of applications that were dealt with at a monthly sitting of the Coromandel Warden’s Court: James, Alexander and Jane Clune had all made separate applications for a building site at Kuaotunu; all were granted. Whether or not this application was made by James Snr or James Jnr is unknown?

Further proof of this Clune family’s trail was found in the 1919 NZ Census which put William, James Snr and Alexander’s son, Alex Clune Jnr, working together as bushmen in Kuaotunu. Again they were recorded in similar locations as bushmen through to 1935, in both Gumtown (Coroglen) and at Table Mountain (in the Coromandel Forest Park). This particular Census record suggested James Clune Snr had been the most likely applicant for the building site.

Uncertain beginnings

It was against this background that Daisy and James Clune Jnr were ‘branded’ with their Clune family name. Unravelling James Jnr and his sister Daisy’s personal circumstance since their births I imagined would be a breeze by comparison. In writing this story, I have considered James and Daisy as if they were born of the same circumstances (father) but as I went on with the research, it appeared James and Daisy had realistically spent very little time with each other growing up. That can be a blessing for some brother and sister relationships but for these two, given they seemed to go from pillar to post in their later lives, they must have wished at times they had had the stability of a regular loving family, a home and siblings to play with as they grew up. All of these were to be denied them, and to boot, they also appeared to have grown up not really knowing their biological mother or father, and in the knowledge they were both most probably illegitimate.

The traditional practice of extended Maori families taking in and raising as their own the children of unwed parents, was a prevalent in the early part of last century and still occurs occasionally to this day. Such children may initially have been cared for by a biological mother, but circumstances (age, inability, death etc) usually dictate that a mother’s whanau will make arrangements for the care (‘adoption’) in the best interests of the child. The following will give the reader an insight into the upbringing of James Jnr and Daisy and just how the lives of children in similar circumstances might evolve.

Daisy Clune – 1894

Daisy Clune was initially cited in her brother James’s military file as his Next of Kin. Daisy’s address at the time was recorded as, “c/o Mrs F. Cleaver, 5 Cross Street, Newton, Auckland”. This provided the clue which allowed me to work backwards to uncover Daisy’s early life but unfortunately it did not identify hers or James’s mother.

William Cleaver had been an early settler who arrived in Auckland in the 1850s. By 1870 he was married with children and residing in Thames. His son William Jnr was a publican in Thames (later becoming a Tailor). In 1880 William Snr and family, including William Jnr’s wife Charlotte, were living at Tairua Landing on the Coromandel Peninsula. It is believed that this move bought the Cleavers into contact with the Clunes. Undoubtedly William Jnr, then a publican at Tairua, would have come into contact with the Clune brothers, William Jnr and James Snr who after they left Auckland worked as gum-diggers only 20 km away at Gumtown (Coroglen) at the head of Whitianga Harbour.

By 1900 the Cleaver family (William Jnr, a Tailor) had moved to Mercury Bay, Whitianga. Their son, Frederick Herman Cleaver, also became a Tailor while Fred’s sister Charlotte Jnr became a nurse.

It is this family that took Daisy Clune in after she was born in 1894. Whether or not the Cleavers knew the woman who gave birth to Daisy, or whether they had adopted her as an act of benevolence or necessity – sister Charlotte being a nurse and having the necessary skills to care for a baby if the mother could not (unable to cope, died, abandoned ?), can only be speculated upon. Whatever the case Daisy Clune grew up with the Cleaver family at Whitianga, becoming their domestic help as soon as she was of working age.

As Daisy approached her 16th birthday she was the victim of a serious assault in Whitianga that was widely reported in the major daily newspapers:

A SERIOUS CHARGE. AUCKLAND STAR, VOLUME XLI, ISSUE 121, 24 MAY 1910

(By Telegraph:— Press Association.) WHITIANGA, this day. At the Magistrate’s Court yesterday Daniel Wilson, a half-caste- Samoan, was charged that he did, on the 14th. May at Mill Creek indecently assault one Daisy Clune, a female under the age of l6 years. Wilson, was committed to stand his trial at the next sitting of the Supreme Court.

Fred Cleaver married Mary Elizabeth “May” Whitaker in 1907 and the had moved to Auckland after Fred had accepted a position with the Crown Stocking Company.

In Nov 1912 Daisy (18) fell pregnant to an unknown father. Her baby boy she named Leo Clune, was born at Kuaotunu, Coromandel in July 1913 however did not survive beyond four months of age. This suggests Daisy was sent to Alexander and Jane Coom Clune’s to have her baby. Whether the name “Leo” was a clue to paternity would be at best pure speculation.

As the war approached the remaining Cleaver family moved out of Whitianga and took up residence at 5 Cross Street in the city along with Fred and Mary. As the householders, Fred and Mary by default became Daisy Clune’s foster parents. Daisy (19) continued to ‘work’ for the Cleaver’s as a domestic and housekeeper. While with the Cleavers, Daisy met a young newly graduated Police Constable named Ernest Francis JONES (1890-1986), formerly a Carpenter of 237 Waltham Road, Sydenham in Christchurch. Ernest had been posted from his police training in Wellington (c1911-1913) to the Newton Police Station in Auckland the same suburb that the Cleaver’s Cross Street house was in.

Ernest and Daisy’s relationship flourished and within two years, they were married in 1916. Ernest Jones was a career policeman whose next posting was to Marton followed by Cambridge. Here he was promoted to Sergeant and posted back to Auckland in 1938. Daisy and Ernest had five children together, two sons and three daughters. Following WW2, Sgt. Ernie Jones was posted to his hometown of Christchurch where the family took up residence at 140 St Albans Road in St Albans, the Jones family home for the remainder of Daisy’s life. Daisy died unexpectedly in 1950 at the age of 55. After retiring in 1957, Ernie Jones lived on for almost 30 more years later until passing away in July 1986 at the age of 96.

James Clune (Jnr) – 1895

James Clune Jnr was born at Hikuai on 2 February 1895. No birth registrations are recorded for either James or Daisy Clune and therefore other than James Snr Clune being listed as James’s father in his military file, no parental records for the two siblings exist, not even on Daisy marriage certificate. From the information above we can conclude their mother was Maori, and as James Snr Clune had been born in Tasmania of white European Irish parentage, James Jnr and Daisy would likely be ‘half-caste’ in appearance – the photograph of Daisy proves this.

The only indication James Jnr had been fostered apart from Daisy was his military record references. “Mrs J.W. Anderson, Kopu” was his nominated Next of Kin / point of contact. This had later been ruled through and replaced with “Mrs J.H. Anderson (Guardian), Heall St, Thames.” The address had later been altered to: “c/o Mrs Ashley, Orere Point, Clevedon, Hauraki Plains.”

After the war James Clune Jnr’s medals and Certificate of Services Rendered had been addressed to: “Mrs J.H. Andersdon (Foster Mother)”, c/o Mrs Ashley … etc., in June 1922. This was all I had to go on to try and establish who had been responsible for James, pre-WW1. I will address this in the paragraph “Tracing Daisy and James” below. James’s military record at least allowed me to construct a picture of his military service.

‘For King and Empire’

16/570 Private James Clune was registered for military service at Whitianga with the territorial 6th Hauraki Regiment. At that time James was working for Mr John Morrison, a store keeper in Hikuai, up until the day he was enlisted in 1915.

Pte. Clune (20) was called-up for service with the 2nd NZ Native Contingent which would supplement those of the 1st Contingent already overseas in Malta. He was enlisted at Auckland on 30 June 1915 and attested at Takapuna in July, and clearly without schooling as one of the recruiting staff, Pte. Turoa Royal, a soldier designated as “Recruiting for the Native Contingent”, signed James’s enlistment documentation for him – James made his mark with an “X”. The Contingents training was undertaken at Avondale Racecourse and from where the men were sent home on final leave before embarking for service overseas. Pte. Clune was both nervous and excited about the prospect of going overseas with the Army. So many new experiences faced him – travel out of the Hawkes Bay, new friends, army training, a uniform, travel on a ship, foreign countries and of course the fighting that was required at their destination – many more questions were yet to be answered, and for all of the members of the 2nd Native Contingent, NZEF.

Now is the hour …

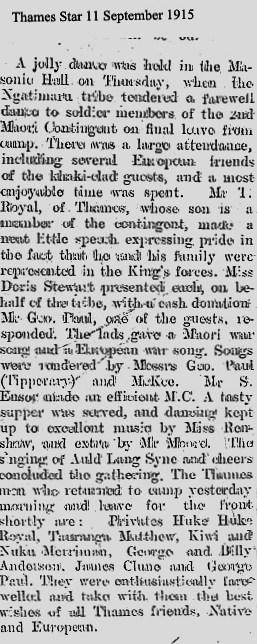

A farewell dance in Thames on Thursday, 9 Sep 1915 was hosted by the Ngatimaru iwi for eight local boys of the 2nd Native Contingent who were on final leave before returning to camp the following day. The men, enthusiastically farewelled by locals and their pakeha soldier mates, were: Pte. James Clune, Pte. Kuke Huke Royal, Pte. Tauranga Matthews, Ptes. Kiwi and Nuku Merriman, George and Billy Anderson, and Pte. George Paul. Each was gifted with a cash donation after which they jointly responded with a Maori and a departure European war song.

HMNZT 29 Waitemata sailed from Wellington with the 2nd Native Contingent aboard on 19 September 1915, arriving at Suez on 26 October. For political reasons the 1st Contingent had been stationed at Malta and not employed in the April landings at Gallipoli however, this stance changed very quickly in the face of unexpectedly heavy losses that the regional battalions suffered during the landings. The 1st Contingent was rushed into service on Gallipoli and from their arrival at Anzac Cove in July 1915, Maori soldiers were engaged in combat, but also carried out trench digging and other labouring tasks. Maori played a prominent role in the August offensive, taking part in the assault on the approaches to Chunuk Bair. Like other units on Gallipoli, the Native Contingent suffered high casualties with only 134 of the original 477 Maori soldiers withdrawn from Gallipoli on 14 December 1915, when Allied forces evacuated the Peninsula. A total of 50 had been killed in action or died of wounds or disease, while the rest had already been withdrawn to Egypt, sick or wounded.

Suez, Egypt

The 2nd Native Contingent, destined to join the remnants of the 1st Contingent (re-named the NZ [Maori] Pioneer Battalion), was disembarked at Suez and ferried in smaller craft up the Canal to Ismailia and the ANZAC Mounted Rifles base camp at El Moascar. The camp was situated in the desert about a mile to the westward of the town and was bounded on the southern side by the aptly named ‘Sweet Water’ Canal which separated it from Lake Timseh, and on the eastern side by the Abbasia Canal. To the north was open desert, mainly hard sand, and to the west cultivated ground by the banks of the Canal which paralleled the railway to Cairo. The town of Ismailia, which owes its origin to the French engineers and employees of the Suez Canal Company, is situated at the junction of the Port Said, Suez, and Cairo railway lines.

During World War I the El Moascar Isolation Camp (a separate camp within Ismailia) provided a location for all deploying troops to be medically checked and prepared prior to their entrainment to Alexandria and Gallipoli or the Western Front. The Isolation Camp also screened all soldiers arriving in Egypt. They stayed in the camp for two weeks, were checked for any illnesses and contagious diseases such as measles, and briefed on their self management in desert condition – hydration, protection from sun, salt intake and so forth.

In January 1915 Pte. Clune was posted to the NZ Pioneers (an element of NZ Engineers) attached to the Auckland Infantry Battalion (AIB) in preparation for deployment to France. The AIB embarked at Port Said (northern end of the Suez Canal on the Mediterranean coast) on April 9th and sailed for Etaples, France.

Battle of Flers-Courcelette – Somme

The first action the NZ Division was to become embroiled in was the Somme Offensive which had been initiated by the British Fourth Army and Reserve Army, and the French Sixth Army were pitted against the German First Army on 01 July 1916 and would run for nearly six months. The NZ Division, which included the AIB (and Pte. Clune), was blooded in this Great War at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette which involved the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers on the northern edge of the Somme in northern France. It was also the first campaign in which tanks were used (by the Canadians) in the First World War.

Pte. Clune and the Pioneers had their work cut out particularly as the NZ Division battled into their first winter on the Somme. On 2 November Pte. Clune’s unit was in Fleurbaix, 8 km south-west of Armentieres, when he was taken ill with severe pneumonia and evacuated to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station. I imagine his promotion to Temporary Lance Corporal on 16 November was of little comfort to him at the time. On the 28th L/Cpl. Clune was transferred briefly to a field hospital where he was put on to an Ambulance Train for transfer to No.13 British General Hospital (a converted Casino) in Boulogne. At 13 GH he was diagnosed as having a Tuburcule Left Lung and was embarked on HM Hospital Ship St. Patrick on 9 Dec to be evacuated England and No.1 NZ General Hospital, Brockenhurst. Pte. Clune’s regimental number at this time was also altered from 16/570 to 16/570A while at Brockenhurst. While the precise reason for this change is unknown, it was quite common for regimental numbers to be inadvertently duplicated and so the last to be designated with a number already assigned, had A or B added to it.

By the end of Jan 1917, Pte. Clune had recovered sufficiently to return to the NZ Base Depot at Codford. Two weeks later he was again admitted to the Codford Camp hospital (No.3 NZ General Hospital) with shortness of breath and a hacking cough. Since his first diagnosis, James’s overall weight had plummeted by 15 kilograms from his enlistment weight 82 kgs. In early March he was medically re-assessed by specialists and classified as “UNFIT” for active service. He was enrolled for immediate evacuation to New Zealand.

HMNZ HS Maheno departed from Liverpool on 18 March and arrived in Auckland on 6 May 1917. A reassessment by more Army medical specialists recommended that James be admitted to the Te Waikato (Tuburculosis)** Sanatorium near Cambridge. Accordingly, Pte. James Clune was discharged from the NZEF on 18 June 1917 and delivered to the administering Thames Hospital.

Note: Tuberculosis (TB) was known at this time by its colloquial name “Consumption”

Te Waikato

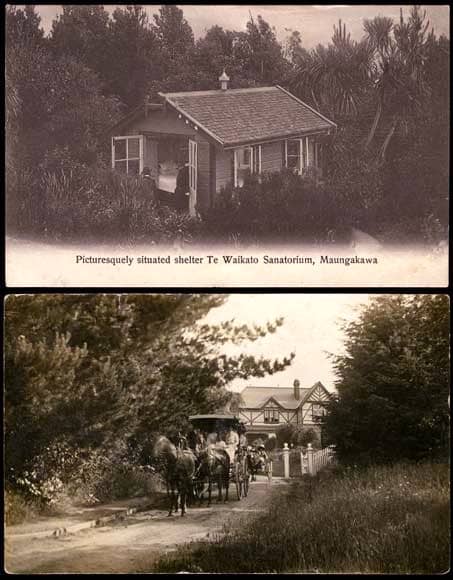

In September 1902 the government established the first open air sanatorium for Tuberculosis sufferers in New Zealand. A former private home belonging to the Thornton family it was officially called Te Waikato Sanatorium. Cambridge had already acquired the reputation as a resort for TB sufferers and a sanatorium operated at the foot of the Maungakawa Hill (later known as Sanatorium Hill). It was stated that the climate in Cambridge was much drier than in most parts of the North Island and meteorological instruments were installed to assess data.

Opened on 11 December 1903 by Sir Joseph Ward, Te Waikato supplied a very desperate need in New Zealand and many sufferers saw their salvation in the opening of its doors. The Department of Health was besieged with applications. The treatment and facilities offered at Te Waikato were particularly suited to the treatment of early cases. One regulation made six months the limit of treatment, except under special circumstances. At the time of opening there was space for about thirty patients but it was obvious from the number of applications that this was inadequate. Further additions gave accommodation for over 60 patients with possibly some 160 later undergoing treatment annually.

The Matron, Miss Annie Rochfort, introduced handcrafts to her patients – now occupational therapy. Patients who were fit to work helped to build a workshop for themselves from which they turned out many useful articles. Beehives and nest boxes were made in the workshop from kerosene cases, as well as general maintenance to furniture.

During the First World War Te Waikato filled a desperate need in the Waikato for convalescent servicemen. To simplify administration the Cambridge Sanatorium (100 beds) was restricted to male patients, and the Otaki Sanatorium (34 beds) to female patients.

Many old diggers recall the good deeds of the “marvelous Cambridge ladies”. The cardigans and socks they knitted, the baskets of fruit and in particular the ‘strawberry days’. Cambridge people did much in relieving the monotony and isolation of the patients by organizing concert parties. ‘Te Waikato’ closed its doors for the last time in 1922.

James Clune was admitted to Te Waikato on 24 September 1918 as a ‘special circumstances’ case and so his residency became semi-permanent. It can only be imagined that James’s sister Daisy, his father James Clune Snr, his former guardian and foster-mother, Mrs Anderson and possibly others who new James, had an opportunity to visit him. Given the distances involved and infrequency of available transport, visits would have been limited. Besides that, TB is a highly contagious disease and so visiting would have been strictly controlled, if permitted at all?

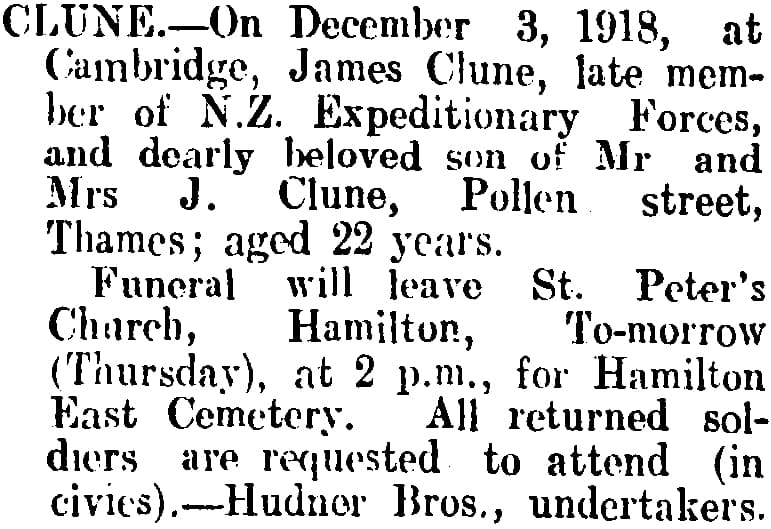

Having been admitted to Te Waikato, James Clune was destined never to leave. He died from the disease on 05 December, 1919. A funeral was held at St Peters Hamilton on Thursday 06 December at 2.00 pm and thereafter, James Clune’s body was laid to rest in the Hamilton East Cemetery.

At just 23 years of age, James Clune’s life had ceased before it had really begun ….

Medals: British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal

Service Overseas: 1 year 231 days

Total NZEF Service: 1 year 354 days

In Nov 1921, James’s foster-mother, Mrs J. H. Anderson, received his medals and Certificate of Services Rendered. In August 1923 she further received his Memorial )’Death’) Plaque, an Illuminated Scroll and a form Letter of Condolence from the King George V.

Note: Other members of the Clune family to serve during WW1 were:

76505 Private Alexander Clune Jnr (Farm Hand) – ‘E’ Company, NZ Rifle Brigade – 40th Reinforcements NZEF – embarked in September 1918 and served for 1 year 175 days in England only. Medals: British War Medal, 1914-18 only.

40513 Private Leonard John Clune (Sawmill Hand) – ‘A’ Company, Auckland Infantry Regiment – 23rd Reinforcements NZEF – embarked in March 1917, and served for 295 days overseas in England only. Invalided back to NZ with Tuberculosis. Medals: British War Medal, 1914-18 only.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Daisy Clune’s foster-father:

55038 Rifleman Frederick Herman Cleaver (Tailor) – ‘J’ Company Reinforcements, NZ Rifle Brigade NZEF – embarked in July 1917, and served for 1 year 343 days overseas in France and Belgium. He returned to NZ in 1919. Medals: British War Medal, 1914-18 and Victory Medal.

One further newspaper item that initially was puzzling was this – Pte. James Clune’s Death Notice appeared in the Waikato Times on 4 December 1918:

After much head scratching over who exactly “Mr & Mrs J. Clune – Pollen St, Thames” were, I was able to establish the lady alluded to as “Mrs Clune” in the notice (above) was in fact Agnes Burnett ROGERS (34), the daughter of George ROGER and his wife Agnes, nee BURNETT, farmers of Razorback, Raglan. Agnes Burnett Roger had been born in 1891 at Papakura (then known as Drury), the family residing there until moving to Razorback, Raglan in the 1880s where George Roger started breaking in his farm.

The “Mr J. Clune” in the above notice proved to be James Jnr’s father, James Clune Snr. This I determined from marriage records that showed James and his ‘wife’ did not actually marry until 1920. At the time it was probably both prudent and discreet for James and Agnes to present as husband and wife, not only for the sake of James Jnr’s funeral, but also to silence any potential for gossip as the two had been living together in Agnes’s Pollen Street house and would continue to do so until they were able to formalise their marriage. Once married, James and Agnes settled on a small farm at Rangiriri West near Raglan, not that far from Agnes’s parents property at Razorback. James Clune Snr settled into a regular and unhurried routine which was a far cry from his earlier days when he and his brothers had been under the strident influence of their reprobate father George.

James Clune Snr died at his Rangiriri West farm in March 1950 at the age of 86, his Agnes also at Rangiriri in 1962, aged 75. Both are buried together in the Catholic Section of Rangiriri Cemetery.

Tracing Daisy and James

Kopu is about 30 km west of Hikuai and is a major highway junction – from here go north to Thames, west to Pokeno, or south to Paeroa. James Clune’s military file recorded his first point of contact (nearest relative) as: Mrs J. W. Anderson, Kopu. I located a 1903 death record for a James William Anderson, labourer, of Kopu who had been born in Tasmania. Given that James’s father and brothers had been of Irish/Tasmanian extraction before immigrating to NZ, it would not be to much of a stretch to make a link that both families new each other well.

Exactly what Mrs Anderson’s relationship to the Clune family was is not known and beyond the scope of this research. However the fact that James’s subsequently changed his records by re-designating Mrs J. H. Anderson to be his “Guardian” and later his “Foster-Mother” together with the fact his medals were addressed to the same person at Orere, Clevedon, Hauraki Plains, suggests the Anderson families were connected. The other link, albeit tenuous, was the fact that James Clune had gone overseas with both George and Billie (William) Anderson who were at the farewell dance – possibly sons (or fostered children?) of one of these Anderson families.

A Clune descendant

Given the uncertain identity of James Clune Jnr’s extended family, the one constant connected to him was his sister Daisy (Clune) JONES. Since Daisy and husband Police Sergeant Ernie Jones had remained reliably traceable throughout Ernie’s police career, they were easy enough to follow, and more so once they had settled in Christchurch. From here I was able to pieced together the families of Daisy and Ernie’s children.

Daisy and Ernest Jones had five children together: Ernest Raymond Lee JONES (1914-2009), James Francis JONES (1917-2005), Grace THOMSON (1918-1986), June Hazel BATES (1919-1993) – Australia, and Nola Jean LOWE (1924- ). Whilst I was attempting to make contact with a grandson of Daisy’s, I was contacted by Louise Thomson of Reefton. Louise is the daughter of Grace and Errol Thomson, and grand-daughter of Daisy Clune Jones. She is therefore the grand-niece of Daisy’s brother James Clune Jnr.

Louise had been alerted to the existence of James Clune Jnr while working on her genealogy and that of her grandmother Daisy Clune Jones. As a result she discovered James Clune Jnr’s war service record in the Auckland War Memorial Cenotaph site. Attached to that file was a message from MRNZ inviting contact from descendants for the medal named to 16/570A Private James Clune that we were holding.

Having made that contact, Louise is now the very proud owner of her grand-uncle, 16/570A Private James Clune’s 1914-15 Star.

Note: If you can help to locate James Clune’s British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal, I would very much like to hear from you.

The reunited medal tally is 239.