10/1741 ~ HENRY RAYMOND BEVAN

Naval Captain Simon Rooke, RNZN, a senior NZDF officer contacted me after having found a First World War medal whilst sorting his deceased father’s personal effects. The Victory Medal, in good condition complete with original ribbon, was named to 10/1741 PTE H. R. BEVAN N.Z.E.F. As is often the case with these sort of medal finds, not a name that either Captain Rooke or his wider family associated with anyone known to them. This can sometimes be due to an incomplete knowledge of a family’s ancestry, given the nuances that can exist with marriages, divorces, births, adoptions and deaths that can occur at any time during a family’s history. Without regularly tracking such events as a family historian might, it can be extremely hard to stay abreast of the connections as families grow. However more often than not, singular medals are acquired as the result of a spur of the moment purchase in a second hand-shop, sometimes they may turn up in an unlikely place, or occasionally they are gifted to the owner. In Captain Rooke’s case no obvious reason was apparent as to “why” or “how” the medal had come to be in his father’s possession.

Deciding the medal should if at all possible go back to the Bevan family, Captain Rooke’s first port of call for help was the NZDF Personnel Archives and Medals subject specialist. Karley was able to provide Captain Rooke with the soldier’s basic service information but had nothing regarding Pte. Bevan’s family contact, beside this soldier he had been dead since 1950. Previously Karley has referred a number of cases such as this to MRNZ and we have been able to assist medal holders locate descendant families. Karley referred Captain Rooke to MRNZ with his request and I glad to be able to report we were able to successfully assist him return the medal.

Who was Henry Bevan ?

Henry Raymond Bevan was born in Otaki on 8 March 1895. This case had piqued my particular interest from the outset having lived in Otaki in my teens and attended the college there prior to my enlistment in the NZ Army. In reading through Henry Bevan’s military file I recognised the names of several families belonging to college students I had known particularly well, families that by 1970 were probably very much larger and complex than in Henry Bevan’s day.

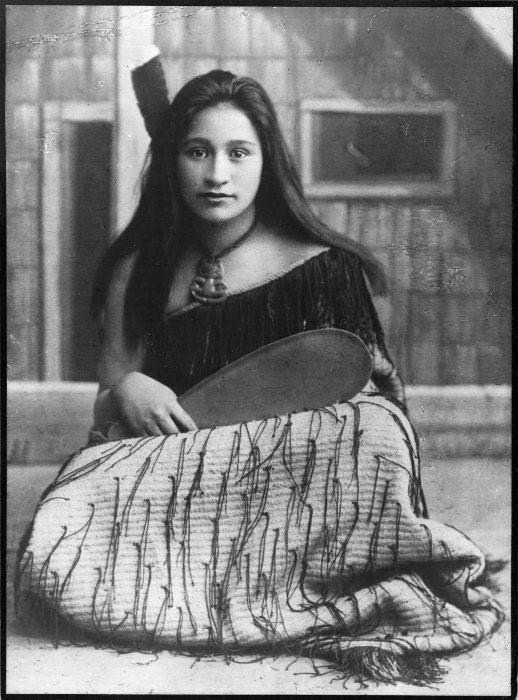

From Henry’s record I could tell, despite having a very English/Irish sounding name, that there was a definite Maori connection in his upbringing. From personal experience I knew the Bevan name to be prolific in the Manakau/Ohau areas, small rural settlements about mid-way between Otaki and Levin on the state highway. Given that Otaki was built up around an historically significant marae and church (Rangiatea) in the middle of today’s township (pop. 5,800 in 2013), I concluded Henry could possibly be of Ngati Raukawa parentage. It also meant that the convoluted and diverse nature of relationships within an iwi over such a long period since Henry’s birth, could make this a bigger task than I first imagined. but having some knowledge of the Ngati Raukawa families in Otaki, I was confident of finding a descendant (if there was one) with whom we could reunite Henry’s Victory Medal.

My search started with the basics (military file, censuses, BDM records, family trees) with the first strong lead coming from an on-line family tree. Other than negotiating the usual pitfalls of conflicting information one comes across when comparing family trees from a diverse range of authors (some not well informed but rather cut ‘n’ paste genealogists) I found sufficient corroborated evidence to Henry’s uncle William ‘Bill’ Bevan (Junior) whom he had recorded as his Father in his enlistment documentation. This gave me a specific line of descendants to hopefully link Henry to – all I had to do was prove the connection. Easier said than done goes the old saying which was going to be the case with this family, and there was a twist – all is never as it seems when dealing with blended families.

Growing up in Otaki

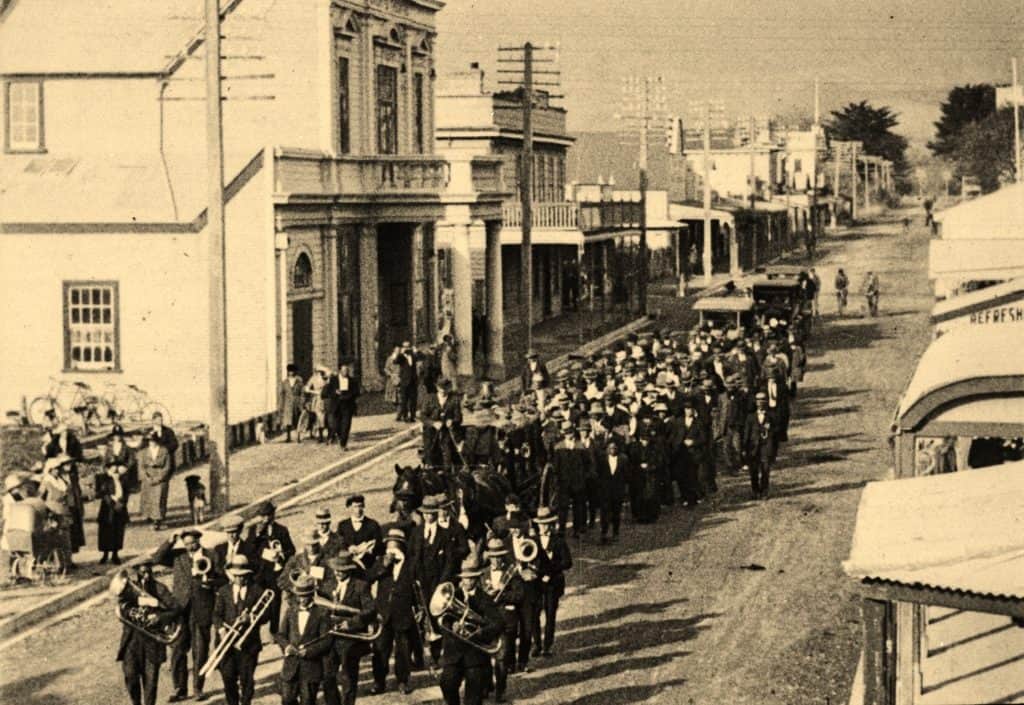

The spectre of the South African (Boer) War of 1899-1902 had come and gone for Otaki by the time Henry Bevan was six years of age. Henry grew up in the fold of the Ngati Raukawa iwi. The Marae located in the centre of what is now the Otaki township, was the 1830s hub of three pah; the Otaki pa and Katihiku settlement on the south side of the river, and the Rangiruru pa on the north side with the Pakakuhu settlement further north. The Raukawa Marae on the north side is in the shadow of the historic Rangiatea Church and so young Tom learned from an early age what it meant to be of Ngati Raukawa descent – proud, loyal and fearless in a faith based society. Henry by all accounts was all of these things.

For Henry hard work was instilled in him as being a way of life with priorities centred around feeding and housing the whanau. Any opportunities for developing a source of income came second. Trapping eels and inanga, river and sea fishing from the mouth of the Otaki River, digging shellfish at Otaki Beach (4km east), trapping birds, hunting and cultivating food stocks (gardening). There was plenty of hard physical work required of the young men of Ngati Raukawa which also included collecting firewood, water, tree felling, bush clearance, pit-sawing timber, ploughing, waka construction, building and maintenance tasks. A physical life that built young Henry into a strong and resilient lad, qualities which would prove to be a distinct advantage to him after he had been introduced to the game of rugby.

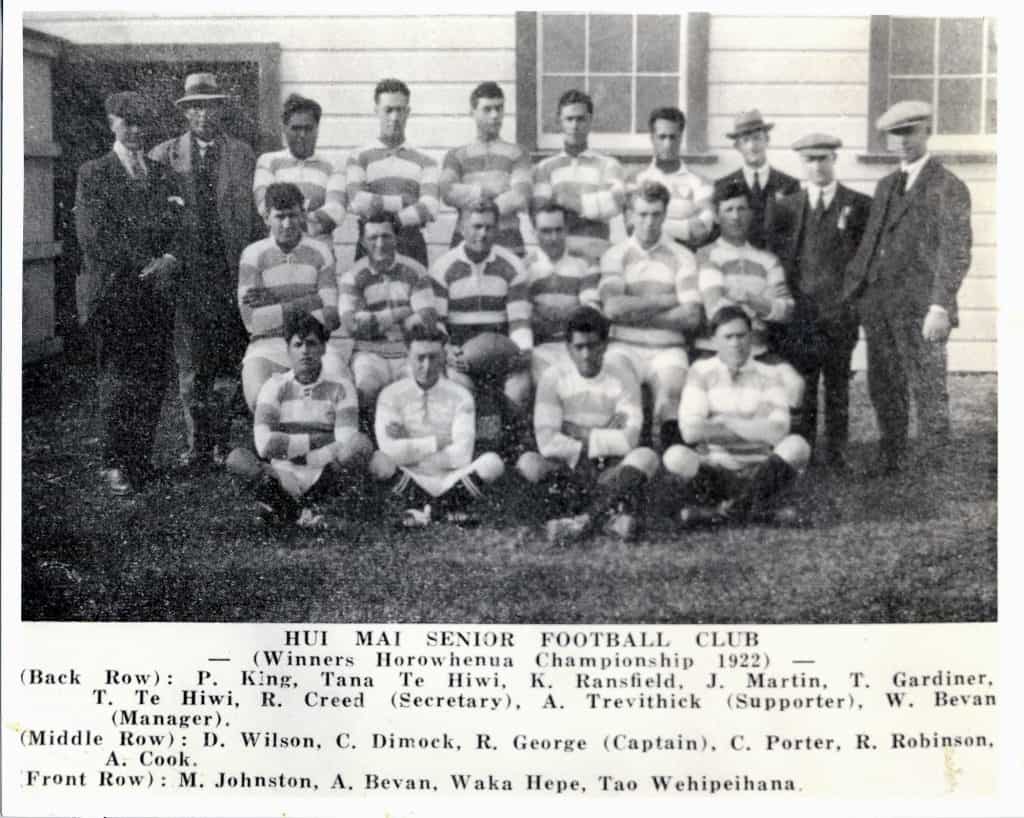

Henry had started playing rugby as a young boy, a game that took on a far greater significance as he got older. Henry excelled at rugby, he loved it. His early membership of the Hui Mai club in Manakau was his introduction to the Horowhenua Rugby Football Union. The strong sense of team and loyalty to a tight group of team mates and to his Club he learned from this association and never wavered during his lifetime. Henry’s skills on the field made him a valued player for the Horowhenua union and set him on a path to potential national recognition.

When Henry was in his early teens he started working full-time for his uncle William ‘Bill’ Bevan who ran a carrying business in Otaki (initially horse and dray, later a truck based owner/operator business). As the possibility of a war in Europe loomed on the horizon during the 1910s, there was plenty of work on for a carrier as the older men in the Otaki community started to disappear for periods of part-time military training – just in case.

Henry’s origin … with a twist

As I looked deeper into Henry’s origin, it was clear that this could be a story all of its own but for the sake of trying to keep this post brief (as possible?), I will touch on the highlights only.

William David Bevan [Senior] (1838-1913] had originated from Whitchurch in Shropshire, England. William was only three when his parents Thomas and Mary Bevan and their seven children, left Whitchurch and emigrated to New Zealand aboard the Lady Nugent in 1841. An eighth child, Nugent Bevan, was born during the voyage but did not survive and was buried at sea near Sulawesi, Indonesia.

The family gradually moved north from Wellington until settling in Manakau. Young William (a roper maker) married Tauranga born Ani (Annie) Ngapaki Te REI (1851-1912) and established himself in Otaki. Their family of eight children were; Mary Josephine (1876-1912), Sarah (b1876), William “Bill” Bevan [Junior] (1877-1950), David Te Rei Tewi (b1879), James Charles (b1882), Margaret Miriama (b1884), Cecelia Hiria (b1887) and the last, Thomas Kenneth Bevan born in 1889. All four Bevan girls were married in due course however the eldest, Mary Josephine at 19 years of age and unmarried, unexpectedly gave birth to a baby boy whom she named Henry Raymond Bevan.

I could find no official record of Henry’s birth which in itself was not unusual given the circumstances and the time in history. The only written references to be found was in the entries of Henry’s WW1 military Attestation paper and his WW2 enlistment record, which state he was born at Otaki on 8 March 1895. Oddly enough Henry’s WW1 Medical History sheet states that his date of birth was “11 Nov 1895”? A likely clerical error as it was circled in blue biro!

The twist – while growing up with the Bevans, Henry knew he had been born in Otaki but what was not clear to him as he got older, was the reason for his slightly different facial features from those of his brothers and sisters. Although no record of Henry’s natural father exists, family folk-law has it that the reason for Henry’s appearance was his father was of Chinese descent

The Chinese have a long history in Otaki. They had been some of the earliest immigrants to NZ with their interests apart from gold mining, being agriculturally based business opportunities. The Chinese established market gardens and sold produce from Wellington to the Manawatu, with the Horowhenua area being of particular interest due to the rich alluvial soils that produced outstanding root and leaf crops alike. Otaki, Manakau, Ohau and areas further north towards Levin were, and still are, renowned for the large market gardens and quality of produce grown for local and national consumption, as well as export. The Chinese were numerous at this time and at the forefront of the market gardening industry in Otaki and Horowhenua so the possibility of a relationship between a Chinese man and Mary Josephine which resulted in Henry’s birth, whilst unusual, was not out of the question or unknown.

Early days with Raukawa iwi

Mary Josephine being young and unprepared for motherhood, and in Baby Henry’s best interests, he was unofficially ‘adopted’ by his Ngati Raukawa whanau. Henry’s ‘adoption’ by whanau effectively meant he was whangai (the customary Maori practice of a child being raised by someone other than their birth parents) which in those days was commonplace. This practice included all children, irrespective of the circumstances of their birth (e.g. illegitimate, orphaned, abandoned), or those born to a girl not old enough to take on the responsibility of motherhood.

Ka mate kāinga tahi ka ora kāinga rua.

(When one home fails, have another to go to. Have two strings to your bow)

When Mary Bevan turned 20 in 1896 she married Alfred Robert KNOX in Otaki. Whether or not Mary had wanted to keep Henry was not up for debate. He was settled, safe and in good care of whanau where he remained. Mary and Robert left Otaki to live in Lower Hutt, Wellington and subsequently had a family of five children. Mary J. Knox died in September 1912; both Mary and her husband are buried in St Peter Chanel Cemetery, Otaki.

‘Uncle’ Bill & ‘Aunty’ Maata

Bill Bevan Jnr. (1877-1950) was born in Otaki and in 1902 he married Otaki woman, Maata Hokepera CLARK (1885-1929). Clearly of Maori descent Maata’s English father, Harry (Henry T.W.) CLARK and her Maori mother Mere Makaora ROACH, had named their daughter “Martha Isabell Clark”. This name appears on her BDM birth record and Marriage Certificate, but generally she was known as either Maata or “Bella” (I will use Maata from this point) by anyone who knew her.

After they were married Bill and Maata bought Bill’s young nephew Henry (then about 6 years old) back into the Bevan fold by keeping him under their wing and raising him as one of their own children – Henry at last had a permanent family and, albeit de facto, two parents. Henry was in very good hands with Bill and Maata Bevan, and of course young Miri Bevan until she herself was married. Miri was Mary J.’s and Bill’s younger sister, Margaret Miriama Bevan who later married a Whare GRAY, and Charles Moses (Mohi) WINTERBURN. Miri at the tender age of eleven was a constant companion of Baby Henry, looking after his basic needs and safety, in conjunction with the other whanau mothers. Growing up Henry was always surrounded by children his own age, many of them from the numerous connected Bevan families which were geographically spread over a large area between Otaki and Palmerston North, with the largest concentration outside Otaki being the families living in Manakau. Whichever way Henry eventually went in the future, in spite of any appearance concerns he might have had, he would always be part of the large extended Bevan and Ngati Raukawa family and whanau environment in Otaki.

But all of this mattered not. As far as Henry was concerned he had only ever known his “Mum”s to be either ‘Aunty’ Maata or his ‘Aunty’ Miri. As for his “Dad”, for as far back as Henry could remember Maata’s husband ‘Uncle Bill’ had been his father and remained so until such time as Henry was old enough to understand otherwise. As for formal adoption, under these types of circumstances it was unheard of in a marae setting – that was a requirement of the pakeha world, and so Henry’s whangai status was never (never needed to be) altered by a formalised adoption.

“TOM Bevan”

From an early age, to his family and friends Henry Raymond Bevan had been known simply as “Tom” (thank goodness his name was not “Bill” – there were quite enough of these between Otaki and Manakau!). In later life Henry was known by his family, certainly by the next generation of Bevan children, as “Uncle Tom”.

Tom’s schooling had been minimal. As soon as he was old enough (12 or 13) Tom went to work with his Uncle Bill in his carrying business. As a lad Tom had been introduced to rugby which he apparently took to like a duck to water. By the time he was 18, Tom stood 5 foot 5 inches tall (172.7 cms) and weighed 150 lbs (68 kgs) wringing wet. He was no giant but working with his uncle in the carrying business built him into a physically solid specimen who could not only move at speed but was fearless in confrontation. The more he laboured the stronger he became proving an asset to any team he played for. Although compact, having hands like ‘a kilo of sausages’ was Tom’s hallmark as was his ‘take no prisoners’ and ‘go-forward’ attitude on the rugby field making him a formidable opponent on attack or in defence. For all that, Tom Bevan is still remembered as a gentle man, quiet and unassuming (until he had the ball in hand!).

Horowhenua Rugby Football Union

Tom Bevan was one of a long line of Bevan men from both Otaki and Manakau to play rugby for Horowhenua. The Horowhenua Rugby Football Union (HRFU) was formed after a meeting at Manakau on April 29, 1893 – two days after the first AGM of the New Zealand RFU. Manakau RF Club had actually been constituted a year earlier in 1892 with Hui Mai Club one of its most enduring clubs. The Union was only admitted to the NZRFU in June 2018.

The earliest record of rugby in Manakau goes back to 1899 when M. Carruthers and W. Greenhough played for the Horowhenua team. Rugby Union records show that in 1903 the Manawatu-Horowhenua representative match was actually played in Manakau. In 1905 there was a club called the Swainson and Bevan Football Club and it is thought there were then the two clubs in existence. In 1908 five players from the Hui Mai Club and five from Manakau represented Horowhenua but by 1909, Manakau had disappeared from the records but Hui Mai remained for many years until about 1938 when it combined with Kuku and formed the Kuku-Manakau Club and in 1939 this club won the Championship. 1946 again saw Hui Mai as the preferred name and it continued under this name. However at the beginning of 1951 season, Hui Mai were unable to field a senior team and two of its most prominent players, Roy Robinson and Graeme Bryant transferred to Athletic and the club gradually faded out and went into recess.

Bill Bevan Jnr. had played for Hui Mai RFC in 1906 and the club had stood the test of time in being able to field a Senior team whilst the Manakau RFC had not. As a result the Manakau RFC club name was dropped in favour of Hui Mai RFC. It was a natural choice for Tom to join Hui Mai rather than the alternate of Otaki’s Rahui RFC. It is not known exactly when Tom joined the Hui Mai club but by the time he was ready to go overseas with the NZEF in 1915 he was playing senior grade rugby, 17 years of age being the minimum playing age for seniors.

Great War or Great Adventure

At a time when the daily topic of conversation in Otaki was the War, as it was everywhere else in the country, the attraction of an opportunity to travel by ship to the other side of the world and then having a bit of a scrap with those who would seek to do them harm was all the inspiration Tom Bevan needed to enlist. Tom (19) was excited at the prospect of going overseas with the NZEF.

When the government called for volunteer reinforcements, Tom Bevan and some of his playing mates did not hesitate to join up. He was enlisted in Wellington on 6 January 1915 and completed his medical at Trentham on the 8th. Tom flew through his medical checks – physically fit, 20/20 vision, no defects, no operations, he had gained a kilogram in weight, and his teeth required no work – 100% working order. He was declared fit for to deploy overseas.

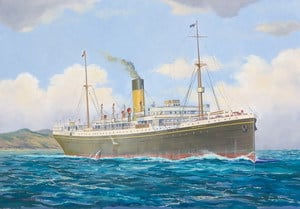

Tom presented himself to Trentham Camp on 22 Jan 1915 and signed the dotted line of Attestation that bound him to serve with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) for the duration of the war. 10/1741 Pte. Henry Raymond (Tom) Bevan was first placed into the Maori Contingent and on 17 Feb assigned to the Wellington Infantry Battalion (WIB). He completed the 8weeks of basic training at Featherston Camp after with he returned to Otaki for 10 days pre-embarkation leave. Eight days before the Landings at Gallipoli in April 1915 were due to happen, Pte. Bevan embarked HMNZT 21 Willochra with the WIB’s 4th Reinforcements, departing from Wellington on 17 April 1915 for the Port of Suez in Egypt.

The Willochra arrived at Suez on 26 May and discharged the reinforcements who then travelled by train to the NZEF’s Zeitoun Camp on the outskirts of Cairo. At Zeitoun they would start training and preparing for their first action in the Dardenelles, Turkey – Gallipoli was a name that was fast becoming known world-wide. The WIB reinforcements re-embarked in July at the Port of Alexandria, situated at the northern end of the Suez Canal in the Mediterranean Sea, for the 1058 km voyage to Lemnos, an island about 120 kms from Anzac Cove used as a HQ and staging post for troops being ferried into Anzac Cove. Pte. Bevan had been placed with the 17th “Ruahine” Company,** the other three companies of the battalion being the 7th (West Coast), 9th (Hawkes Bay) and 11th (Taranaki). He arrived at the Peninsula on 21 August as part of a two officer and 77 man reinforcement group. The

Battle for Chunuk Bair two weeks prior had taken a huge toll on the Wellingtons, particularly the former Wellington Mounted Riflemen who had volunteered to join the battalion as reinforcement Infantrymen. The Wellingtons were in control of most of the trenches on Hill 60, however a second attack was necessary to re-take those forfeited to the Ottomans during the first attack. The attack was launched on 27 August and it was during this Pte. Bevan was wounded in the left hand. Whilst his hand was healing, he was put on less demanding duties with his one operable hand, on the beach in the stores compound. For the next three and a half months Pte. Bevan managed to avoid further injury having returned to almost full duties. Fortune must have also smiled to allow him to escape the carnage so many others had experienced whilst on Gallipoli Peninsula – a command decision had been made to evacuate the ANZAC forces from the Peninsula in December 1915.

Note: ** In early 1915 the government sent the New Zealand Native Contingent (also known as the Maori Contingent but intended to include Pacific Islanders) to join the New Zealand forces in Egypt. Its soldiers were drawn from iwi across the country and it was eventually organised in companies corresponding to the four Maori electorates. Its officers and senior NCOs were drawn from the four regional regular battalions of Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury and Otago.

The Maori Contingent was initially assigned to garrison duty in Malta, but manpower shortages on Gallipoli due to the high casualty rate, led to serving there as labourers and infantry from August to December 1915.

The Contingent was reconstituted as a Pioneer Battalion in early 1916, as part of the newly-formed NZ Division which was about to move to the Western Front. Two of the Pioneer Battalion’s four companies were made up of the former Maori Contingent, with the other two drawn largely from the Otago Mounted Rifles. A mix of Maori officers and NCOs filled the battalion’s executive and command appointments while soldiers from the Otago Battalion were added to supplement the rank and file.

Pioneers were not front-line fighting units but a military labour force trained and organised to work on engineering duties, digging trenches, building roads and railways, and taking on other logistical tasks. This was essential and dangerous work that was often carried out under fire.

The Pioneer Battalion served with the New Zealand forces on the Western Front from April 1916, and in September 1917 was re-designated the New Zealand Maori (Pioneer) Battalion when all its companies were filled by Maori.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The ANZACs returned to Cairo where the remnants of all units were reorganised into a new configuration of the NZ Division which in essence dispensed with many of the Mounted units, keeping only sufficient for the Egyptian Expeditionary Force operations in the Sinai and along the Suez Canal, and re-rolling the remainder of the Mounted Riflemen to foot-slogging Infantry. The survivors of Gallipoli were also the only experienced troops the NZ Division had at that point and so these personnel were given the added responsibility to train and mentor the green and untested reinforcements as they arrived from New Zealand.

They say “idle hands make the devil’s work” and Tom like most other young soldiers was not immune from getting into strife on occasions. Tom did not suffer fools lightly and a result, his propensity to ignore directions from those he had no respect for invariable caused a clash of wills. To say Tom was argumentative would not be correct however he was not backward in coming forward when challenging that with which he did not agree, or was accused of. Unfortunately these circumstances together with some rather poor time management on his part at times, got Tom offside with the brass on more than one occasion.

In July 1916 while in the field, Pte. Bevan left a Divisional Bathing Parade without permission and remained absent from 3.30 pm until 8 pm. As a consequence he was charged, found Guilty and received a sentence of quote, “To suffer 21 days Field Punishment (F.P.) No.2” (not a prospect to be relished by even the toughest of nuts). On a second occasion in May 1917 he received another 7 days F.P. No.2 – no reason is specified.

In Dec 1917 the 17th Ruahine Company was attached to the Canadian Tunnelling Company to assist their Tunnellers with some of their trenching and associated earthworks. 30 May 1918 bought about a complete change of pace for Pte. Bevan when he was appointed a Cook for the last seven months of his time overseas, finally relinquishing the job on 29 Dec. Men were regularly seconded to this task given the huge numbers that needed to be fed, a means of resting men from the front as well as accommodating those recovering from injuries or other impediments that made them unemployable in the front line. A posting to the cook house was also used as a means of applying ‘close supervision’ to those who required it.

Rugby and WW1

At the New Zealand military training camps in Egypt – first at Zeitoun near Cairo and later Ismailia on the Suez canal – games were played between the various units of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. These games were not friendly social occasions, as was often the norm when played by Englishmen. Instead they became an extension of provincial rivalry. The Otago Battalion and Wellington Battalion would battle it out in the hot desert sand, which was a change from the heavy muddy grounds of Athletic Park or Carisbrook. Players and spectators wrote home to their families boasting of their unit’s victory.

Even within battalions there were rugby games between platoons, one such game being fought over a day’s ration of jam! A ‘Canterbury Infantryman’ wrote home after witnessing a game – ‘No. 3 and 4 platoons tried conclusions in a most exciting game. The stake was a day’s ration of jam and the teams, therefore, took the game very seriously. It was as wild as one could possibly wish for, and there were no “beg pardons.” No.4 won by a penalty goal to nil, but play was very even … No. 3, in consequence, had no jam today, but they are in hopes of getting a double ration at a future date.’

Wherever there were sufficient men gathered with nothing better to do, a ball and something that passed for a playing surface, there was always a rugby game (of some sort) being played in the NZEF. Pte. Bevan played every chance he got. As a staunch and valued player of the Horowhenua Union, Tom’s star had been on the rise before the war, the chances of a call-up for the NZ Maori team considered a distinct possibility. Service with the NZEF also gave Pte. Bevan opportunities to play a diverse range of teams (and playing styles) from the participating Allies, thereby maintaining his skills.

The Somme Cup. The New Zealand Division had begun organised rugby matches in 1916, as it had other sports, with the aims of maintaining soldiers’ fitness and morale and giving them something to do when not involved with military duties. The Division’s best players had been assembled at a base camp in France and mixed rugby training with instruction courses such as grenade-throwing and machine-gunning. Tom Bevan was one of the elite footballers of the New Zealand Division.

The French newspaper, Le Journal, arranged and sponsored a soldier vs soldier rugby match to be between France and New Zealand in Paris on Easter Sunday, 1917. This game would be ‘curtain raiser’ entertainment for war weary Parisians prior to the regular Sunday French team fixture. The two teams would field their best available for the Sunday match, winner take all; the NZ team were dubbed the “Trench All Blacks.”

The NZ Division had played seven matches in the lead up to Easter Weekend, against similar teams made up of military men and had amassed 292 points and conceded just nine. Their only close encounter was a 3-0 win against a Welsh Division XV (the significance of the score not being lost on rugby fans who knew all too well the outcome of the test against Wales in 1905). The game had been played in Belgium in early 1917 when the noise of bursting shells every so often drowned out the shouts of the crowd.

According to Le Journal, a crowd estimate of 60,000 people crammed into the ground at Vincennes in the east of Paris for the game. Some papers, including in New Zealand, reported it as a world record attendance for a rugby match. The rugby, meanwhile, was a one-sided contest with New Zealand winning 40-0. Le Journal called the performance a masterly lesson in athletics.

“Our men had to bow to world champions who beat the Irish army, the Welsh team and the British air force. The result of 40-0 was nevertheless honourable and was proclaimed in a storm of cheers and a burst of fraternal esteem.”

The French captain, four other French players and two NZEF players who played, would be killed in battle within weeks after the match.

The newspaper had also organised another French soldier, Georges Chauvel, who was a sculptor in peacetime, to fashion a trophy. He produced a statue of a French soldier in the act of throwing a grenade and called it, “le Lanceur de Grenades” (the Grenade Thrower, literally the Launcher of Grenades). But the New Zealand and French footballers called it the Somme Cup, or the Coupe de la Somme, and that is what it has remained.

Now an in-active trophy, the “cup” is displayed at the National Army Museum in Waiouru or the Rugby Museum in Palmerston North on special occasions. The “cup” is the only survivor of that international clash of rugby might in Paris 102 years ago on Easter Sunday 2019, and is currently sitting on the mantelpiece of a private home somewhere in New Zealand.

Original text courtesy of Ron Palenski – http://www.nzrugby.co.nz/ww100/rugby-and-the-first-world-war

The Moascar Cup. Every time schoolboys play for the Moascar Cup they are continuing a tradition that began on the sands of Egypt toward the end of the First World War which endures to this day.

The fighting being over in Nov 1918, some troops remained until the early months of 1919, partly because there were not enough ships available to get them home. British, New Zealand (including Henry) and Australian soldiers camped at Moascar in Ismailia, at the northern end of the Suez Canal, formed the Ismailia Rugby Union and organised a competition.

The Ismailia Rugby Union also arranged a trophy cup – described as “a handsome Irish cup” – and had it mounted on a piece of a wooden propeller from a German aircraft shot down in Palestine. Thus, the Moascar Cup came into being and was won by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Unit and Depot, which won nine of its ten matches. Rugby was not just an idle kick around in the sand. The New Zealanders had a final match at Amiens then returned to active duty.

“The contest assumed an international aspect both because of the personnel of the teams and the high standard of play attained” one who was there wrote. The Cup was brought home and presented to the New Zealand Rugby Football Union on condition that it be a challenge trophy for secondary schools. It continues to be played for annually, over 100 years since the end of the war and is one of the most coveted prizes in First XV rugby.

Footnote: When the New Zealanders captured Le Quesnoy from the Germans on 4 November 1918, the Union Jack that flew from the town hall had been consecrated and presented to the New Zealand (Maori) Pioneer Battalion by the Maori schoolchildren of Otaki and Levin.

Going home

Pte. Tom Bevan’s only other injury sustained whilst serving overseas was during a rugby game. His left side ribs were severely fractured while in the bottom of a ruck playing a home game in Feb 1918 at the 1st NZ Infantry Brigade School. Thanks to the skilled attention of the 3rd NZ Field Ambulance, Tom was spared permanent damage and in due course recovered to play again. Unfortunately for Tom his injuries ruled him out of the 1919 NZEF Services team tour to England and France – rugby and Tom would be out of the question until he was back in NZ.

By the end of the war Pte. Bevan had managed to come through almost three and a half years oat war on the front line with nothing physically more serious than a hand wound and crushed ribs. In retrospect, given Pte. Bevan had fought in most of the NZ Division’s major battles areas, from Gallipoli in Aug-Dec 1915, the Sinai desert, Egypt Feb-May 1916, to the Western Front and Courcelette in Sep 1916, Messines and Passchendaele … it is surprising he lived to tell the tale!

In early January 1919 the Wellington Infantry Regiment personnel were directed to assemble on board the SS Zealandic, a former White Star Line (Titanic) ship, for demobilization. By the 18 of January ‘demob’ was complete and the ship left Southampton with Pte. Tom Bevan aboard, headed for Wellington. Three weeks into the voyage Pte. Bevan made the fatal mistake of incurring the wrath of the 17th Ruahine’s Company Sergeant Major Bowie once again, by failing to carry out his duty as a Mess Orderly when ordered by the CSM. Pte. Bevan was charged with “Conduct to the Prejudice of Good Order and Military Discipline”, was found Guilty and awarded 14 days in the ship’s cells plus the loss of 21 days pay . The Zealandic arrived in Wellington on 28 March 1919.

With demobilization of the WIR completed prior to their departure from England, 10/1741 Pte. Henry Raymond Bevan was discharged from the NZEF with effect from his arrival back at Trentham whereupon he was issued a train travel warrant, some money to buy a demob suit, and returned to his Uncle Bill Bevan’s home on the Main Road at Otaki, a place he had not set eyes on for four years and three months.

Medals: 1914/15 Star, British War Medal, 1914-18 and Victory Medal; ANZAC (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion (1967) and Lapel Badge

In 1967 the ANZAC (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion and a Lapel Badge of the same pattern was available to all Returned Gallipoli Veterans. The catch was Veterans had to apply for the medallion. The Medallion only was available to the next of kin of those soldiers who were killed at Gallipoli or had subsequently died.

Service Overseas: 3 years and 318 days

Total NZEF Service: 4 years 91 days

Note: 17/17 Trooper David Bevan – NZ Veterinary Corps, 2nd Reinforcements (farm labourer Otaki). Tpr. Bevan was the brother of Bill Bevan of Otaki. Born in 1879 he was 35 years of age when he was enlisted in Oct 1914. Placed in the NZ Veterinary Corps to be a Saddler, David Bevan embarked in Dec 1914 and served in Egypt and with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Ismailia and Sinai, France and Belgium. One month after his arrival in England his employment was altered to Farrier. In April 1916, David was transferred to the NZ Field Artillery, as a Driver with the Divisional Ammunition Column. After several hospitalisations in 1916 which included his evacuation to No.2 NZ General Hospital in England, David Bevan’s “Debility” was attributed to a pre-existing condition, Hydatids of the Lung plus long standing evidence of Tuberculosis. Tpr. David Bevan was classified ‘medically unfit’ in July 1917, repatriated to NZ and discharged from the NZEF in Nov 1917. David Bevan died at Otaki in 1950.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Otaki’s rising star

Within a matter of weeks Tom (24) had re-connected with his old team mates at the Hui Mai Club in Manakau and settled into a reasonably relaxed routine of work, and rugby … more rugby than work! He also found that there were quite a number of Bevans playing for Hui Mai by the time he returned, mainly from the Manakau and Ohau families. The team at that time was flush with Seniors for the current season which meant that if he wanted to play, he would have to do so with another Horowhenua Union club until he could be re-absorbed into Hui Mai. Tom played his 1921 season with the Kimberley team in Levin. Aware of his NZEF rugby form, Tom was watched closely by selectors while he was with Kimberley. They were suitably impressed which resulted in his selection to play in the 1921 NZ Combined Unions XV against Wellington (Won 58-6), and also a visiting the Springbok side (Lost 9-3) – a very creditable result considering the Boks were a well drilled and rehearsed international side.

Tom’s years – 1922 & 1923

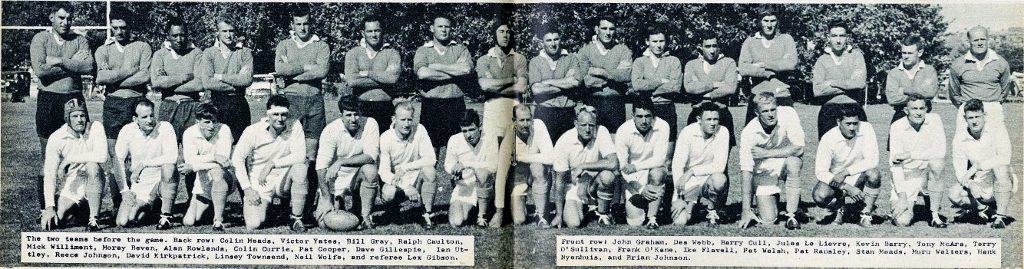

1922 and 1923 were to be Tom Bevan’s biggest years in 1st class rugby. Tom played for the NZ Combined Unions team against Wellington in 1922 which unfortunately resulted in a one point Loss, 16-17. He also got the call once again for the NZ Maori team who would be undertaking an internal tour of New Zealand which would be split either side of an Australian tour. They would play three games before they went to Australia and three more on their return. Of the NZ games, NZ Maori won three, lost two and drew one.

NZ Maori played three tests in Australia. Having never beaten an Australian XV in the 12 years they had played them, the 1922 NZ Maori team redeemed themselves with a Win in their first test against a very tough NSW side. The second test was played the following Monday which resulted in the NZ Maoris and NSW both changing a number of players in the dying minutes of the game as a result of the tough encounter during the first test. NZ changed seven players. The final test against a NSW XV resulted in a one point Win to NZ Maori, 23-22 and the series Win, 2-1.

The team returned to a hero’s welcome and continued with the second half of their NZ tour. In Napier the NZ Maori side played the All Blacks for the very first time which resulted in a loss to NZ Maori. For Tom Bevan however there was better news, after the tour he would be returning to his old Hui Mai club at Manakau. In addition, Hui Mai RFC had collected the trophy for the HRFU’s Club Championship for the first time since 1909.

Tom’s form was at its peak in 1923. He was selected for a North Island Combined Unions team to play Wellington, recording a Loss, 11-19. Another successful tour to Australia followed and was capped at the end of the year with the Hui Mai club taking out the HRFU Championship for the second year running. Tom also played in the inaugural internal Maori regional competition, the teams competing for the Te Mori Rosebowl.

From 1924-1933 Horowhenua (HRFU) and Manawatu (MRFU) unions decided to combined and became Manawhenua (MRFU) which rationalised the number of teams the unions they could afford to support while having a viable competition.

Tom played for the Otaki RFC in 1924. 1925 was to be his last year playing for the NZ Maoris after which he continued to play first grade club rugby with Otaki and Hui Mai. In 1927 Tom at 32 years of age decided to call it a day on his playing career, and as if it were all meant to be, his last hurrah with his beloved Hui Mai included the club’s winning of the MRFU Club Championship once more.

Tom was a loyal supporter of Hui Mai RFC for as long as the club lasted (until 1932) and the Horowhenua RF Union through all its iterations. His allegiance to both the HRFU, MRFU and the Horowhenua-Kapiti Rugby Union (as it became) never wavered over the years and remained his life long interest.

Given Tom Bevan’s somewhat anonymous start in life, he had more than made up for that with his rugby career, proving himself to be an outstanding sportsman by anyone’s standard. He could take pride in the fact that he had made his mark on the game, and accordingly was entered into the history books of NZ Army (NZEF) rugby, NZ Maori rugby, and his beloved Hui Mai club and the Horowhenua-Kapiti Rugby Union as it had become). He cannot be forgotten.

Leaving Otaki

In 1929 Tom’s adoptive ‘mother’ Maata Bevan died and shortly thereafter husband Bill (61) retired from his carrying business. Bill’s eldest daughter Winifred May “Wynne” Bevan (1902-1961) had moved with her family to Taua Tapu (commonly Tawatapu), a small town that support a growing Public Works Dept (PWD) village/camp at Pukerua Bay near Plimmerton.

The village and camp accommodated the many contractors and PWD workforce engaged on major PWD projects such as upgrading and expanding the existing State Highway 1 into a motorway from Pukerua Bay through to Plimmerton, and the re-build of a new and enlarged Paremata Bridge. Wellington being the capital city was growing at the rapid rate post WW1 and traditional access was not copping with steady increase of vehicular traffic that was becoming a preferred mode of trade and personal transport. Added to this was the effect the re-location to Titahi Bay in 1917 of the international communications cable that linked New Zealand with the rest of the world, to Titahi Bay. The original cable had come ashore in NZ at Cable Bay in the Nelson area and supported by a small cable station. Cable Bay was considered too remote and so the cable was re-routed to come ashore at Titahi Bay. This of course had required substantial supporting infrastructure all the way to Wellington plus the manpower to build it. It was this new cable that really kick-started the overall development and growth of this whole area from Pukerua Bay to Johnsonville/Ngauranga which continued for the best part of the next 25 years. Accordingly this saw the rise of vibrant suburbs from the once sleepy, rural hollows that bordered the state highway, such as Plimmerton, Titahi Bay, Tawa (formerly Tawatapu) and Johnsonville.

Tom Bevan decided to follow suit and in 1935 landed a job at Tawatapu as a labourer for the PWD (later known as the Ministry of Works – MOW). Here he would be able to maintain regular contact with his family via Wynne, and to see his Uncle Bill whenever he came down from Otaki to stay with his daughter.

Home Service – WW2

With the advent of WW2 Tom Bevan (now 45) registered for re-enlistment once again. He was called up on 11 January 1941, still single, and cited his Uncle Bill Bevan (back in Otaki by this time) as his next of kin. Given Tom’s former service, wound and his age, he was eligible to perform Home Service only. His work with the PWD lent itself to him being enlisted in the Corps of NZ Engineers in the rank of Sapper (the Engineer equivalent to an infantry Private).

2/5/612 Sapper Henry Raymond (Tom) Bevan – NZE was once again in uniform. In Feb 1941 Sapper Bevan was posted to 22 Field Company which was based at the Ngaruawahia Military Camp, 20 km north-west of Hamilton. From here Spr. Bevan did various work in support of the Winter Show in Auckland, and other tasks at Avondale, in Fielding and in Wellington from served from 1941 to 1942 doing. Tom was released from service in Mar 1942 after a year of service. He returned to Plimmerton and his pre-war job with the PWD. Once the war was over Tom was able to apply for a small Housing Corporation flat in a social housing complex at 62 Waiwhetu Road, Lower Hutt where he lived for the best part of the next 10 years.

For his WW2 Home Service, 1941-1942, Sapper Bevan qualified for two further medals:

Medals: War Medal 1939-45 and the New Zealand War Service Medal. Again, Tom claimed neither of these.

Tom Bevan’s family

Tom Bevan’s prowess on the rugby field was not isolated. As I started to look for connections of living Bevan descendants, it was revealed Tom was not the only family member who had excelled on the rugby field.

Tom’s uncle Bill Bevan Jnr. and wife Maata had had five biological children in their family. As already indicated above, their eldest was Winifred “Wynne” May BEVAN (1902-1961) and it was Wynne’s family that was relationship that was of interest to me. Lewis Victor HOMES and Wynne’s son gained international acclaim as a rugby player at the highest level, in both provincial representative and national rugby team.

Passionate followers of Wellington rugby will instantly recognise the name of Vincent David Bevan. Born in Otaki on Christmas Day 1921, Vincent was even better known by All Black rugby devotees, as Vince Bevan, star half-back and All Black #479.** Vince also served with the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF) during WW2 as an Infantryman (and rugby player) with 22 (NZ) Battalion in North Africa and Italy. (refer extended bio below)

Vince was not the only Bevan to distinguish himself on the rugby paddock. His younger brother Moray Vivian Bevan born in Levin in 1933, had a lengthy rugby career and represented three provincial teams in 1st class rugby – Wellington, Hawkes Bay and Poverty Bay. Moray Bevan’s rugby career was capped by his selection for the New Zealand Maori All Black team 1954-1960.(refer extended bio below)

In 1953 Vince Bevan married Ivy Fay BARROTT, daughter of Walter Joseph and Myrtle Cecelia BARROTT (nee HOLT). Vince and Fay (as she was known) had three daughters and a son: Patricia Carol, Jill Maree, Jan Leonie, William “Bill” David and Vicky Christina Bevan. The Bevan family grew up and lived most of their lives in the Porirua, Tawa and Titahi Bay areas.

Note: ** I received a surprising email on 28 October 2019 that added an update to this post. A gentleman from Otaki had stumbled upon this story of Tom Bevan by chance and stopped to read it as I recognised Tom as being one of his family ancestors. Tom Connor is non-other than the maternal great-grandson of the late Maata and Bill Bevan, and a 3rd cousin to Tom Bevan. Tom tells me the house featured in the photograph (above right) was built by Bill Bevan (probably with Tom’s help!) in 1914 and that since that time it has been occupied continuously by Bevan family descendants. Tom Connor and his family are the current residents of No. 24 Domain Road. The stone wall featured in front of the house however no longer exists.

Thank you for the historic anecdote Tom – Ian, MRNZ.

Marriage lines

Tom remained with the PWD/MOW until he retired at about 60 years of age in 1955. In the interim his uncle Bill Bevan had died in 1950 after which Tom was encouraged by family to leave Waiwhetu Road and move closer to Wynne and some of the other relatives who had moved to the then rapidly growing suburban Porirua. Tom agreed and applied for a house in the area. Since his arrival at Taua Tapu (later shortened to Tawa) was during this time that he had been introduced to a recently widowed lady who just happened to be the 65 year old mother of Vince’s wife Fay Bevan.

Short and sweet

Fay’s mother Myrtle BARROTT had been widowed from her husband Wally Barrott in 1954 after he was killed tragically killed in a car accident. It was through Vince and Fay that Myrtle and Tom Bevan had been introduced to one another. Over the next three years Tom and Myrtle had met intermittently during the course of family gatherings and over time, their relationship had warmed. In 1957 sixty two year old Tom Bevan and Myrtle Barrott (56) agreed to marry … and as they say, the rest was history.

Tom and Myrtle made their home at 16 Kahika Grove, Elsdon in what is now the much enlarged City of Porirua. Kahika Grove still exists as does Tom and Myrtle’s semi-detached, double story home at the top of a street once surrounded by a primary school and other houses. These have all now been removed, leaving a pleasantly spacious and quiet area of trees and grassland.

But … and there is always a but, Tom and Myrtle’s marriage did not endure. Sadly, Tom died suddenly at their home just three years later on 8 December 1960 at the age of 65. He was buried in a soldier’s grave at the Karori Cemetery in Wellington. Myrtle remained in Elsdon for a few more years before moving into the Russell Kemp Home at Titahi Bay where she died on 21 Nov 1976, aged 75. Myrtle Bevan was buried with members of her own family in the Whenua Tapu Cemetery, Wellington.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Notes: ** 234481 Private Vincent David Bevan, 22 NZ (Infantry) Battalion served in the North African and Italian campaigns during World War II and played for the 22nd New Zealand Battalion team (winners of the Freyberg Cup in 1944), the 9th Brigade and 8th Army XVs and the 7th Brigade Group (1942).

The final of the 1944 Freyberg Cup was contested in early December in the ruins of the Fascist Stadium in Forlì in Italy. A tense game was played between the 22nd Battalion team and the 2nd NZ Division Ammunition Company. The match was vigorous, the ground conditions atrocious and the day bitingly cold. It was a tough contest with little opportunity for the backs to shine. Bevan displayed good form and threw a pass to his captain, Lin Thomas, who kicked the dropped goal from the only dry spot on the ground and won the game for the 22nd Battalion, 4–0.

After the war Vince Bevan was selected to play for Wellington College Old Boys before being selected to play for the Wellington provincial team as halfback. In 1947, Bevan made the first of his four appearances for the North Island in the annual inter-island match following which he was selected to be All Black #479. His All Black playing career lasted from 1947 to 1954 in which he played 25 games for the All Blacks including six tests. But for injury, (he had either fallen from a truck or had been hit by a truck near the front line at the end of the War), he may well have played for the famous New Zealand team which in 1945–46 toured Britain and France. The trials for the team were held in Austria and Bevan had shown such good form that his selection had been a certainty.

Bevan’s official All-Black profile says that “he is best remembered for games he didn’t play and the tour he was not allowed to go on. Bevan’s career, indeed, is one of the starkest examples of some of the gross stupidities, even injustices, New Zealand rugby created for itself by trying for too long to fit in with the colour bar, later formalised as apartheid, being enforced in South Africa. Bevan should have been the All Blacks number one halfback on the tour of South Africa in 1949, but an inadvertent reference to his trace of Maori ancestry a year or two beforehand meant he was ruled ineligible to be selected.

His first two test caps came instead in the 1949 series against Australia that was played in New Zealand. This tour coincided with the stronger though Maori-free All Blacks team touring South Africa. Bevan played all four tests the following year against the touring British Lions. Injuries prevented him from touring with the 1951 All Blacks to Australia. Bevan was a member of the 1953–54 New Zealand rugby union tour of the United Kingdom, Ireland, France and North America and played capably enough during his 16 appearances. But with age he was losing a little of his speed and his cousin, Keith Davis, his junior by nearly 10 years, was preferred for all five internationals.

Source: Wikipedia and the Rugby Museum of New Zealand

Footnote: Tamati ELLISON (All Black – 2009, Junior All Black (Capt), NZ Maori (Co-Capt), NZ Sevens) is the grandson of All Black Vince Bevan, and son of rugby Coach Eddie Ellison. He is the older brother of Jacob Ellison, who played prop forward for the Hurricanes.

Moray Vivian Bevan,** was born in Levin in 1933. A keen rugby player from an early age, Moray rose to prominence in NZ rugby after he had moved to Wellington and started playing senior club rugby from around 1950.

While in Wellington Moray had joined the Poneke Football Club at Mirimar where he was soon identified as showing great potential in the lock and flanker positions. The skills he exhibited had not eluded his coaches at Poneke FC, nor the Wellington Union selectors. It was not long before he was selected as a representative for the Wellington Provincial XV which he also Captained on a number of occasions. This however was just a prelude to the pinnacle of his career, yet to come.

Moray Bevan’s provincial performances had caught the eye of the New Zealand RFU selectors which ultimately resulted in 1954 with his first of a series of national caps. Moray played for the NZ Maori All Blacks from 1954-1960. From 1954 to 1958 he had played in the lock or flanker position while also serving as the Vice Captain on occasions. The pinnacle for Moray Bevan came when he was named Captain of the 1960 NZ Maori All Black team which toured Australia and the Pacific Island nations.

In 1961, business interests took Moray to Wairoa, Hawkes Bay where he continued to play senior rugby, mainly with the Tapawai, Ruapanga and Marist Clubs. His ability and experience was obvious and a welcome addition to these teams, some of whom also had a selection of Maori ABs in their ranks. Moray was again selected to be provincial representative, playing for both Hawkes Bay and Poverty Bay in the 1960s. After 10 years playing East Coast rugby, work saw him return to Wellington around 1970 and a return to his old club and playing mates at Poneke FC.

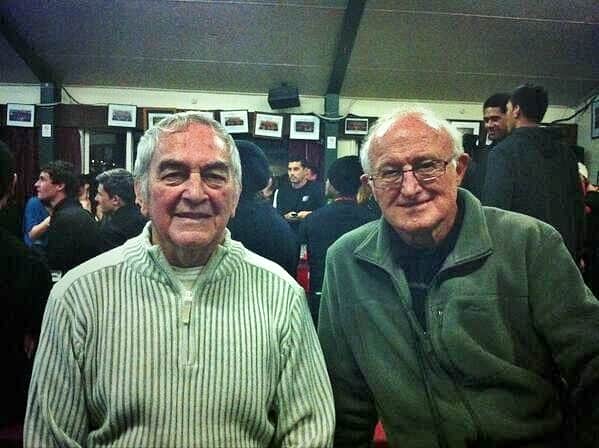

Poneke FC is one of the oldest rugby club’s in the country and could be considered Moray Bevan’s “second home” for the last 45 or so years. During this time he has both played and coached for the Club, assisted with the club’s administration and always been an avid supporting spectator. Moray has also been honoured with Presidency of Poneke as well as Life Membership of Poneke FC. The Club has produced its fair share All Blacks during its 136 year history. Moray Bevan is now part of that history, a respected and revered elder statesman of All Black (Maori), Wellington Union and Poneke FC representative rugby. Moray, now 86 and still living in Wellington, can on occasions still be seen at the Poneke FC club-rooms mixing it with his former Poneke All Black colleagues, and old playing mates from his club rugby days.

The descendant trail …

Tom Bevan’s research trail had proved to be a fascinating one which end with a conclusion I had least expected. In the back of my mind I was still contemplating a visit to Otaki and Manukau to locate a near descendant to return Tom’s medal to. But before I did that, I needed to define a particular family branch to follow which would normally be the one with the most living descendants who were as close to the medal owner as was possible to get. If nothing else, information from branch members helps to narrow the field much more quickly. I started the process of working back from Tom’s death to find living links to his ‘adoptive’ family, Bill and Mata Bevan’s family. I felt the Bevan families most recent long connection with Plimmerton, Titahi Bay and Porirua (city) may yield a prospective family whom I could perhaps approach for information, before I went back to their traditional home in Otaki.

I did the obvious and took a punt on the Wellington phone book. There were 34 results for Bevan families spread from Wellington to Levin, the majority being located (to be expected) in the Otaki, Manukau, Ohau and Levin areas of Horowhenua. The very first three names in the electronic White Pages stopped me in my tracks. Of the list of the 34 these first three ALL included the name “Bill Bevan” in them, AND all three were located in Porirua! I could not believe my luck! Two of thee names were for business addresses (law offices) and the third a private address – what a break!

I decided on the residential number first … within seconds I was speaking to Helen Velvin who kindly confirmed I had the correct family, William “Bill” David Bevan LLB of Kapimana Legal Services Ltd., Porirua being her husband. Helen mentioned the day I called that it was also Bill’s birthday ! … another fortunate coincidence, I was on a roll. I guessed that Bill might be quite pleased with the unexpected ‘birthday present’ I was about bring him and so I phoned him. Bill was certainly surprised with the news, but not half as much as I was. After a brief chat to resolve a couple of burning queries I had regarding his lineage, Bill said the magic words after which I had no more questions – “My father was Vince Bevan” (All Black #479) !

I could not have wished for a better conclusion, nor a closer descendant to Henry Raymond “Tom” Bevan, than his nephew Bill. Not only was he a male descendant and therefore carried the Bevan name (which helps to ensures a medal remains with someone bearing the recipient’s surname) but Bill also turned out to be one of the senior, if not the most senior, direct descendant’s of his father’s step-brother, his uncle Tom Bevan. Bill was delighted with the news of the medal and even more so with what I told him next …

Unclaimed medals

Having focused on just one medal of a trio of WW1 medals Tom had originally been awarded, I noted as the case came to a close that there was no annotation on his file to indicate any claim had been made for the ANZAC (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion (1967). Tom as a returned Gallipoli veteran had been entitled to claim one. However, given he had died in 1950 and the Medallion not being issued until 1967, Tom’s next of kin were entitled to claim this on his behalf. I ran a check with Subject Matter Expert Karley at PAMs who confirmed the Medallion had not been claimed. Karley also advised me that Tom’s WW2 medals for Home Service also remained un-issued/unclaimed.

Whether or not Tom Bevan was ever made aware these medals were available to him, or just didn’t bother about them, is unknown – my guess is probably a bit of both. Tom had seen the worst of war, had spent a considerable amount of time and discomfort amongst it, and lost many friends as a result it. It is a well documented fact that when soldiers return from such catastrophes the last thing on their minds are medals, these mean so little in the scheme of things to many men at such times. Besides, the mental state of every returning soldier tends to shut out the trivial issues such as medals, as irrelevant.

Following WW2 many medals were actively rejected in their thousands with a significant number remaining unclaimed to this day. Apart from post-war lack of interest in the medals, the other main reason for medals being rejected by soldiers was they were protesting. The NZ government in its infinite wisdom had decided against having the medals named before issuing them to soldiers – all First World War medals had been individually named. Many soldiers, sailors and airman considered this penny-pinching act by the government to be an outright insult to their service and sacrifices in facing the horrors they endured and the huge human toll the conflict had taken on comrades, friends, and families at home. This short-sighted decision still causes angst and problems among descendant families to this day, since unlike Australia, South Africa, Canada, India who chose to name their WW2 medals, Britain and NZ did not and so when any of these medals are lost, stolen or even found, there is next to no chance of them being returned to an owner. The upside of the unclaimed medals still held by the NZDF is that it has provided an unexpected bonanza for those families looking for a family member’s medals, believing they had been issued decades ago.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bill Bevan will now be able to add to two more medals to the Tom’s Victory Medal – the War Medal 1939-45 and the New Zealand War Service Medal. In addition he will claim the Anzac (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion (1967). For Bill Bevan, one reunited medal has led to an entitlement to three more – a good deal I would say for any descendant family who started with none. Bill has now received the Victory Medal and applied for the remainder. He is looking forward to an opportunity to honour his uncle Tom Bevan’s memory and service in WW1 by wearing his medals at a future ANZAC or Armistice Day parade.

~ Lest We Forget ~

The discovery and return of Tom Bevan’s Victory Medal begs the question: where are his 1914-15 Star and British War Medal ? If you can help, Bill Bevan or I would very much like to hear from you.

My thanks to Captain Simon Rooke, RNZN for contacting MRNZ. It has been our pleasure to have been of service in reuniting these taonga with the Bevan family.

The reunited medal tally is now 244.