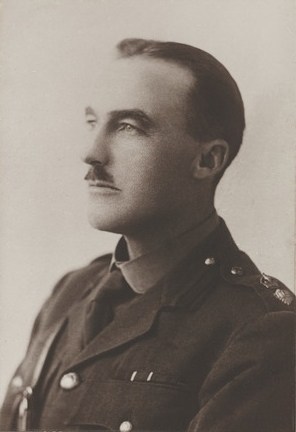

8/1173 ~ GEORGE MITCHELL, DSO, OSK† (Serbia), MP

Some details in this story remain confidential by request.

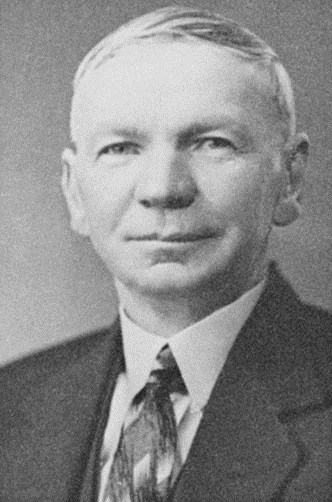

In 2016 I received an enquiry from a gentleman descendant of the late 8/1173 Lieutenant-Colonel George Mitchell, DSO, OSK†, MP who had served in the New Zealand Military Forces during the Boer War and First World War. The enquiry was in relation to Lt-Col Mitchell’s war medals which had last been seen in by family descendants in 1978. Since then the whereabouts of George Mitchell’s medals were an unresolved mystery to his descendant family.

As requested, I listed the Mitchell medals on our website page Medals~LOST+MISSING page with no real expectation of receiving a response for such a unique and desirable medal group. When I learned of the medal group’s composition and a little of George Mitchell’s history, I fully appreciated why medal collectors and aficionados of New Zealand military history would likely have parted with their eye teeth for such a medal group and, the very reason for my low expectation of them seeing the light of day, in New Zealand anyway. The medal group (if in better than good/fine condition) would command a not insubstantial price if placed on the open market in NZ. If sold through a specialist auction house in the UK or USA, a very much higher price could be realised.

Until a few months ago I had heard nothing to indicate Lt-Col Mitchell’s medals were in NZ or even in existence…. and then out of the blue I received a phone call from an unidentified caller asking if I was still interested in locating the Mitchell medals. I replied in the affirmative whereupon the caller advised me the medals were soon to be put up for sale. I asked the caller some questions of clarification re who, when, where and how the sale would be made in an effort to establish the call was not a hoax – the caller would get back to me. I also needed this information before I could go to the person who originally registered the loss with MRNZ. True to his word, the caller replied within a few days and told me where and roughly when the medals would be listed, the “who” however remained confidential. Within a week the listing appeared.

After I had viewed it and familiarised myself with Lt-Col Mitchell’s military service, I understood why his medal group would be most attractive to both collectors and military historians alike. With this information, I had sufficient with which to contact my SE Asian domiciled inquirer, and to confirm that his family’s interest in recovering George Mitchell’s medals remained extant. An emphatic ‘yes’ together with a request for additional information and photographs, I shuttled to and from my source to gather the information requested. Satisfied with my answers, my inquirer gave me the go-ahead to put the wheels in motion to obtain the medals.

Note: In many of the references I consulted while researching this case, George Mitchell is invariable referred to as “Colonel George Mitchell,” not only in the in the newspapers of the day but also on his gravestone at Karori. There has clearly been a misunderstanding of the rank George Mitchell actually held at the time of his death. The references convey the impression to those unfamiliar with military ranks that George Mitchell was a fully ranked Colonel – he was not.

In order to correct this misconception it should be noted George Mitchell was discharged from the NZ Military Forces as a Lieutenant-Colonel (Lt-Col). The error is understandable particularly for those unaware of the protocol used when addressing persons of certain army ranks – I shall explain. It is correct protocol when speaking to a Lieutenant-Colonel (a ‘half-Colonel’ in Army parlance) or a fully ranked Colonel, to address them both as “Colonel”. The rank distinction is more apparent when the officer’s details are in writing; salutations in a letter for instance, can also be written as spoken, e.g. “Dear Colonel so-and-so…” The term is used when writing to a Lieutenant Colonel as well as a fully ranked Colonel. This peculiarity of a single title of address for dual ranks is also applicable to 2nd Lieutenant and Lieutenant, and to Lance Corporal and Corporal.

To possible muddy the waters further, in the 19th & 20th centuries it was common for a high performing and/or qualified officer who was retiring or leaving the service, to be discharged with “Brevet” rank. Brevet (Bvt) rank was an honorary promotion which could be bestowed on officers of Captain’s rank and above (and occasionally an enlisted man) in recognition of gallant conduct or other meritorious service, e.g. Major Jones could be discharged as a “Brevet Lieutenant Colonel A.K. Jones.” However the rank did not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of the Brevet rank. The officer was either being rewarded for gallant or meritorious service and therefore entitled to be addressed as “Colonel” as a civilian, or, that he had met the requisites for promotion to the next higher rank in every respect however opportunity, a vacancy, age or compassionate circumstances preclude the officer from remaining in the service or accepting a position at the next higher rank. In Empire/Commonwealth armies this practice ceased around 1945, was re-introduced in 1952 but was gone permanently by 1960.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

Distinguished service

Lt-Col George Mitchell’s medal group (see note 3) recounts a distinguished career of territorial and active service in the New Zealand Military Forces that spans the period from 1898-1927, including both the 2nd Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 (commonly referred to as Boer War), the interwar period 1903-1914, the First World War 1914-1919, and his post war service until retirement in 1927. Commencing his military career as a mounted trooper, Mitchell held both combat and non-combat appointments in South Africa, Gallipoli (a ‘First Day Lander’), France and Flanders. His personal courage and military dedication during his almost 30 years of regular and territorial military service is reflected in his decorations and medals listed below:

- Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO)

- Queen’s South Africa Medal (1st Cont. NZMR) with Clasps: Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg, Driefontein, Transvaal

- Additional QSA Clasp (8th Cont. NZMR): South Africa 1902; 1st Mention in Despatches (MiD) – note 1

- 1914/15 Star

- British War Medal, 1914-1919

- Allied Victory Medal; 2nd Mention in Despatches (MiD) – note 1

- King George V Silver Jubilee Medal (1935)

- Colonial Auxiliary Forces Long Service Medal (20 years min. service)

- New Zealand Long & Efficient Service Medal – post 1917 (16 years cont. service)

- New Zealand Volunteer Service Medal (12 years service)

- Serbian Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords, 4th Class (OKS†) – notes 2, 3, 4

Notes:

(1) Mentioned in Despatches (or Dispatches, MiD) in the Boer War were awarded for Bravery, Meritorious and Loyal Service. To be ‘mentioned’ meant that the name of an officer, soldier or nurse appeared in an official report written by a superior officer that was sent to the high command, in which their bravery or meritorious service in the face of the enemy was described. At this time there was no medallic award to acknowledge an honourable mention although a bravery medal was sometimes awarded. A mention in despatches did not confer any post nominal letter entitlement on the recipient. For administrative purposes, mid and more recently MiD was used. Promotion was the most usual way of acknowledging an honourable mention; all recipients were published by name in the London Gazette.

From 1914 – Aug 1920 a medal ribbon device was used to denote a ‘mention in despatches‘. A Spray of Oak Leaves in bronze was worn on the ribbon of the Victory Medal. Only one device was added to the ribbon irrespective of how many ‘mentions’ were awarded. Those who did not receive the Victory Medal wore the device on the British War Medal, 1914-18. From Sep 1920, the device used to denote a mention was a single bronze Oak Leaf worn on the ribbon of the appropriate campaign medal. A smaller version of the device was worn on the medal ribbon bar. The award of a Mention in Despatches was replaced in New Zealand by the New Zealand Gallantry Medal in 1999 and also conferred the post nominal letters, NZGM.

(2) Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords is an award conferred by the King of Serbia and both Civil and Military divisions. The awards are identical with the exception that the badge of the Military Division is differenced with the addition of a pair of crossed Swords. The ribbon of the Order when worn on a medal brooch bar has a crossed Swords device added. The Military Division of the Order is awarded in four degrees/classes: 4th = Officer (OSK†); 3rd = Commander (CSK†); 2nd = Grand Officer (GSK†; 1st = Grand Cross (GCrK†).

E.g. Full title of award in the 4th Class is: Order of the Star of Karageorge, 4th Class, with Swords (Serbia)

A recipient of the 4th Class is an OFFICER of the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords

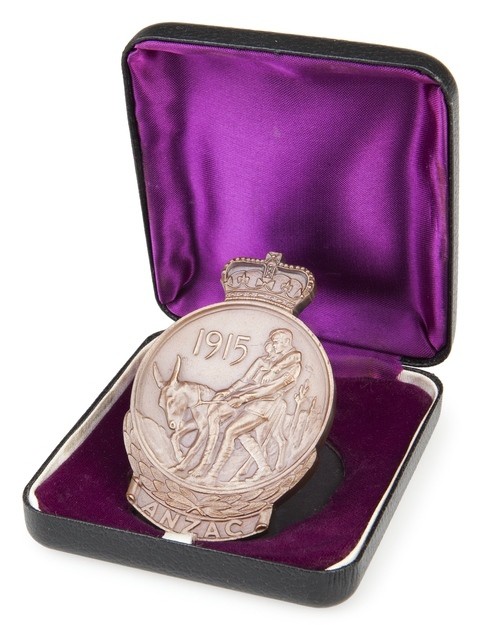

(3) The Order of the Star of Karageorge in Lt.Col Mitchell’s medal group is incorrectly mounted. The Reverse of the Order badge is visible whereas the Obverse (see below) should be facing the forward.

Order of the Star of Karageorge: King Peter I of Serbia instituted the Order on 1st of January 1904, to commemorate his own accession to the Serbian Throne and the centenary of the First Serbian Uprising against the Ottoman Turks, led by the Founder of the Dynasty, Djordje Petrovic, named ‘Black George‘ (or Kara-George) owing to his dark complexion. The National Assembly voted Kara-George the Hereditary Supreme Leader of the Serbs, and the Sultan of Turkey eventually recognized him with the status of a vassal Prince.

During the Balkan Wars (two conflicts that took place in the Balkan Peninsula in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913), a War Merit Division (with crossed swords through centre of the badge) was introduced, to reward conspicuous gallantry of the commissioned officers in the field, as well as (in higher classes) senior officers who successfully commanded troops. The insignia of this Division was worn suspended from a plain red, watered silk ribbon.

During the First World War, Allied countries such as France, Belgium, Russia, Serbia and Italy, exchanged a number of medals on behalf of their country, with their Allied country counterparts (UK, NZ, Aust, Canada, Sth Africa, India etc), to be awarded to worthy recipients. The King of Serbia gave the following awards: Order of the White Eagle with Swords, Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords and the “Obilich” Medal for Bravery, commonly referred to as the “Obilich Medal for Bravery.” The recipients were deserving officers and men who had been nominated by their unit commander for either an act of bravery or meritorious service, when in combat with the enemy. The qualifying criteria for these awards was much less prescriptive than would have been required were the recipient being considered for an Imperial gallantry medal.

(4) The Medal for Bravery like the Order above was conferred by the King of Serbia, for deserving NCOs and soldiers only. Established in 1912 the medal was awarded in two Classes, Gold and Silver, for acts of “Bravery in the Field.” Since 2010 the medal has been called the Medal for Bravery “Miloš Obilich.” The ribbon when worn on a medal bar has a miniature of the medal device attached.

- (Milos Obilich) Medal for Bravery – Gold

- (Milos Obilich) Medal for Bravery – Silver

Founded on 12 July 1913 by King Peter I and granted to soldiers for acts of great personal courage or for personal courage demonstrated on the battlefield. The medal was awarded in two degrees (Gold and Silver medals). The medal started being awarded during the Second Balkan War, continued during World War I 1914-1918, and during World War II, 1941-1945, to members of the Yugoslav Army and of Allied forces. On the obverse of the coin is the ideal figure of Miloš Obilić, the Serbian medieval knight who sacrificed his own life at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, by assassinating the Ottoman Sultan Murad I.

Serbian awards to NZEF personnel in WW1: The Order of the White Eagle with Swords, Classes 2-5 were received by seven General & Senior officers (Major-Colonel); the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords, 4th Class (Officer) was received by only one Senior officer – Lt-Col G. Mitchell, DSO; the Cross of the Star of Karageorge – 1st Class (Sgt, L/Cpl) and 2nd Class (2Lt, Pte); the “Obilich” Medal for Bravery – Gold Medals were received by five soldiers, and the Silver Medal by six soldiers. Total Serbian awards made to the NZEF = 23.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

George Mitchell (Jnr) … his origins

London born George Frederick Mitchell (1851-1926) started his working life as a Labourer later becoming a Plumber’s Assistant in England before moving to Portsmouth and going to sea. As a 17 year old ship’s Fireman, he made his first voyage to Dunedin aboard the fully rigged, 1042 ton wooden barque ESSEX in 1869. The ESSEX was a regular on the trade route from England to Australia at this time whose destination via southern Australia was most Melbourne and Sydney. Since 1869 George had made a number of voyages to the southern ocean and in the course of these George met his future wife, Victorian born Sarah Elizabeth SHORES (1857-1917). Sarah from Richmond and George were married at Richmond on 14 August 1873 after which they sailed to Dunedin and settled themselves in rural Otago at Clyde Street in Balclutha. George sought work as a labourer and within a year of marriage, their first born in 1874: Jane (Mitchell) TOWNLEY was the first of 17 children Sarah gave birth to, 14 of who whom survived into middle or old age: Emma MITCHELL b1875, George MITCHELL (Jnr) b1877, William MITCHELL b1879, Walter MITCHELL b1881, May MITCHELL b1883, Francis (known as Frank) MITCHELL b1885, Harry MITCHELL b1887, Ada (Mitchell) BREMER b1889, Maud MITCHELL b1890, Nellie (Mitchell) MEADS b1892, Not Recorded b1893, Sophia MITCHELL b1894, Arthur Dennis MITCHELL b1896 (also WW1 service), Albert MITCHELL (1897-1897), Mabel MITCHELL b1898, French MITCHELL (1901-1902) and again, French MITCHELL (1902-1957).

The 1880 Balclutha Census showed George F. Mitchell’s occupation to be that of a “Painter” (of buildings, interior/exterior). By 1905 George’s sons William, George Jnr, Walter and Arthur had joined him, also as painters. The increasing popularity and availability of paint with an increasing palate of colours plus a growing range of imported and locally manufactured wall papers increased the popularity and demand for exterior and interior decoration of business premises and private dwellings. That of course required a greater number of tradesmen. George Snr no doubt had foreseen the potential of the business into which he encouraged his sons. The trade also had the added advantage of flexibility in that interior decoration during the bitter Otago winters was definitely preferable to working outdoors, the only option he experienced as labourer or plumbing assistant when he first arrived in Otago.

By the time young George Mitchell had reached working age of 15 or 16 years around 1892, he was learning the ropes of painting and decorating from his father. But George must have harboured another ambition which more than likely arose from the regular appearances of the Volunteer Corps’s mounted riflemen drilling or parading in the town. Whilst happy enough to continue working as a painter for the time being anyway, in June 1898 at the age of 21, George joined the Volunteer Corps as a trooper in the Clutha Mounted Rifles (CMR).

Volunteer Corps

The first recorded meeting to form a volunteer corps in Otago had been held in the Alexandra Hotel at Port Molyneux in 1864. Eighty young men signed up for enrolment. In the same year a meeting was held in Balclutha and from these two gatherings, the first Volunteer Corps was formed. About 1870 local volunteers were firmly established in Balclutha and consisted of two units, No.1 and No.2, the latter drawing members from the Kaitangata and Stirling districts. Captain JP Maitland (the police magistrate in Balclutha) was in command of 50-60 men. The Balclutha contingent drilled in an old stable below the then Court House, but often joined their comrades at Stirling where, when weather conditions were unsuitable, they trained in the Drill Hall at Inchclutha. Inchclutha is a large, flat island sitting in the delta between the Matau and Koau branches of the Clutha River, downstream from the town of Balclutha. Weather permitting drill was conducted on the island’s roads. Collectively the units of the Volunteer Corps in Otago and Southland constituted the 1st Regiment, Otago Mounted Rifle Volunteers which was officially formed on 1st May 1901, its headquarters in Dunedin.

Volunteer Units of the 1st Regiment, Otago Mounted Rifle Volunteers

A Squadron – Otago Hussar Volunteers (Dunedin)

B Squadron – North Otago Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Oamaru)

C Squadron – Clutha Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Balclutha)

D Squadron – Maniototo Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Ranfurly)

E Squadron – Tuapeka Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Lawrence)

F Squadron – Taieri Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Outram)

G Squadron – Waitaki Mounted Rifle Volunteers (Oamaru)

Clutha Mounted Rifles

The uniform of the volunteers was at first a dark grey, but some years later a red tunic, blue trousers with a red stripe down the side and helmet was adopted. Eventually the volunteers disbanded and in 1887/88, the Rifle Club was formed where khaki took the place of the red and blue uniform. About this time the Clutha Mounted Rifles came into existence under Capt John Harvey (of the Bank of New Zealand) who was later to die in action in the Boer War. In 1887 there was a contingent of Otago Hussars in Balclutha under Sgt John Dunne. Capt S. Parmenter, who was associated with the Volunteers, had formerly been a Sergeant-Major in the 18th Royal Irish Regiment and also the proprietor of the Criterion Hotel in Balclutha.

Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902

Source: Owaka Museum/Catlins Historical Society

The South African War (also known as the Second Anglo-Boer War, commonly the Boer War) was the first overseas conflict to involve New Zealand troops. Fought between the British Empire and the Boer South African Republic (Transvaal) and its Orange Free State ally, it was the culmination of long-standing tensions in southern Africa.

Eager to display New Zealand’s loyalty to the British Empire, the Premier Richard J. Seddon offered to send troops two weeks before the fighting started. Hundreds of men applied to serve, and by the time the war began on 11 October 1899, the First Contingent of NZ Mounted Riflemen (NZMR) was already preparing to depart for South Africa.

The first two contingents of mounted riflemen were to be funded by the Government and comprise a mix of career and territorial serving members of from Volunteer Corps units such as the Clutha Mounted Rifles, men who were already proficient in horsemanship and able to fire a rifle accurately from a galloping horse. The remaining “volunteers” would be tested for suitability (physical, medical, horsemanship etc), those who passed the prerequisites used to man future contingents should they be needed (subject to the availability of finance? – future contingents would have to be publicly subscribed or rely on generous benefactors to raise a contingent). As this was to be New Zealand’s first commitment of troops to a military operation overseas, the reputation of its soldiers and therefore the country would be on the line, and so only the most capable were selected for the First Contingent!

An article from the Wellington newspaper EVENING POST on 18 Oct 1920, the day prior to the 21st anniversary of the 1st Contingent’s formation, summed up this sentiment:

FIRST NEW ZEALAND MOUNTED RIFLES – October 21 (Trafalgar Day) will be the twenty-first anniversary of the departure from Wellington of the First New Zealand Contingent for South Africa. The little corps, 214 all ranks, consisted of picked men from existing mounted rifles corps, all of whom were, accomplished horsemen and expert rifle shots. The selection was made from about a thousand recruits, a most rigorous course of exclusion being adopted. The military doctors entrusted with the medical examination of this corps declared that the final selection comprised “the finest lives” they had examined. Indifferent horsemanship or poor shooting were also reasons for rigid exclusion, and when after only a fortnight’s camp at Karori the little contingent was shipped aboard the first New Zealand troopship—the Waiwera—it represented, as far as was possible, the very best military element in New Zealand. Numbers of the men had previous war service, but the bulk were strong, capable, and keen young men from New Zealand stations and farms.

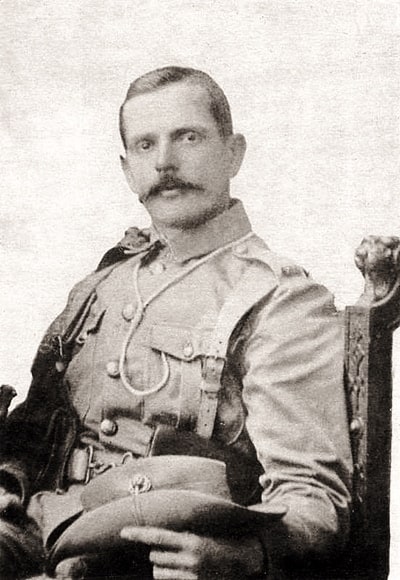

First Contingent

SA-160 Trooper George Mitchell – No.2 Company, 1st Contingent NZMR. Ironically the first detachment of the Contingent to assemble in Wellington on 6 October 1899, pitched their camp on farmland in Campbell Road, Karori, a suburb George Mitchell would come to know very well in later life. The contingent was divided into two companies with a Captain in command of each. No.1 Company consisted of North Island men, and No.2 Company, mostly South Island men with a few Hawkes Bay men to make up the numbers. The Contingent strength totalled 214 men of all ranks (inclusive of a Hotchkis Machine Gun Detachment). In all 18 men had been rejected for want of better horsemanship.

The assembled Contingent, wearing either their civilian clothing or the uniform of their volunteer unit, trained in mounted formation drills and various other basics before embarkation. Uniform and equipment were issued on their day of departure. Trooper Mitchell (23) was assigned to No.2 Company and allocated Horse #160, a Martini Enfield .303 carbine #746, a Lee Metford bayonet, rifle bucket (scabbard) and two ammunition pouches (these were replaced by the leather bandolier later in South Africa). This was his basic fighting equipment. A saddle (British 1890 universal cavalry type), saddle bags, bridle, 1 x water bottle, blanket, Cavalry overcoat, a leather belt, 1 x pr of leather boots, 1 x pr leather gaiters, khaki puttees, khaki jodhpurs (riding breeches), khaki cotton shirts (no pocket or collar), khaki wool socks and underwear, a khaki tunic, khaki Forage cap (Glengarry) for wear in camp, a khaki Slouch hat and brass buttons and badges constituted each troopers basic kit issue.

At approximately 1300 hours on Saturday, 21 October 1899 (coincidentally Trafalgar Day, the anniversary of Lord Nelson’s death), following a parade through the Wellington streets from their camp at Campbell Farm in Karori, the 1st Contingent of New Zealand Mounted Rifles was marched through the Wellington Streets from Campbell Farm to Jervois Quay. They were drawn up in front of a dais from which the assembled troops were addressed by the Governor, Lord Ranfurly, the Premier Richard J. Seddon and the Chief Justice. Once the embarkation of the 214 men and 252 horses of the contingent were complete, the SS Waiwera prepared to cast off. On the harbour was a flotilla of steamers crammed with spectators while an estimated 10-12,000 people gathered at the wharf, bands playing patriotic music, to farewell the Contingent. At approximately 1700 hours Waiwera eased away from the wharf and set sail for South Africa via Albany, Western Australia. She arrived at Capetown four weeks later in the early hours of 20 November 1899.

First blood – Jasfontein

The Contingent disembarked and march six mile to the suburb of Maitland where they spent the next four days equipping and orientating themselves with the help of resident British regiment personnel. After four days the contingent entrained for Naauwport in the Cape Colony to join with the 1st Cavalry Brigade under Major-General French. The Transvaal and Orange Free State (OFS) having declared war on Britain, Gen. French was to locate and capture key Boer leadership personnel such as commanding Generals de Wet and Cronje, whilst destroying their forces. The column would advance first on the OFS capital of Bloomfontein, and then the Transvaal capital at Pretoria. The NZ Contingent would join the Federal Escort to provide reconnaissance, protection and firepower (riding ‘shotgun’ if you will) for French’s Brigade column which comprised approximately 8,000 men, horses, mules, artillery pieces and wagons. The column, a mix of British Infantry regiments, Royal Artillery batteries, South African Scouts, and Australian Lancers were to trek firstly to Bloomfontein, clearing any resistance from the Cape Province before crossing the Orange River into enemy territory, the Orange Free State.

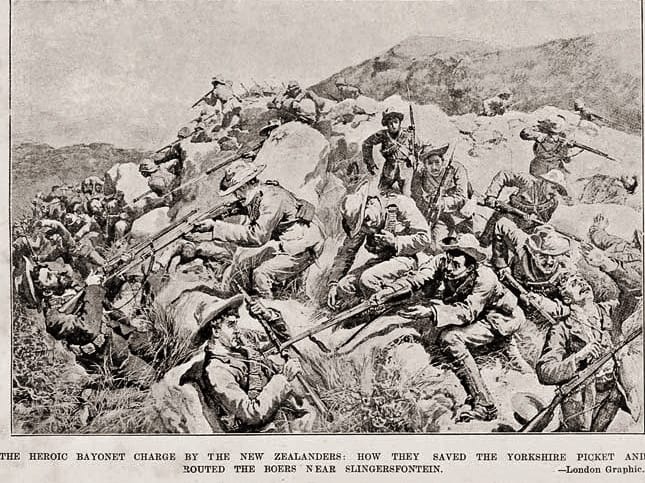

“New Zealand Hill” – The first engagement for New Zealanders on foreign soil came on 18 December 1899 whilst encamped at Jasfontein Farm near Colesburg. Boer artillery shelled the NZers resulting in one trooper killed (Bradford**) and two wounded, one seriously. On 1st January 1900 the Contingent again engaged Boers near Coleskop, Colesburg. Using a mule drawn Boer ambulance, a number of armed Boers hidden inside had been driven up to a kopje (a small hill in otherwise flat surrounding land) in full view of the camp. The Boers then leapt out and disappeared behind the protective kopje. The column continued towards Slingersfontein Farm where it camped on 9 January and was joined by British reinforcements. On 13 January, Boer artillery shelled the camp and 60 troopers of the Contingent were ordered to gallop to a large hill (later named New Zealand Hill) some three miles away and post a picket. Part of the hill was also occupied by the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Regiment. The following afternoon Boer sniper fire pinned down those on the hill until dusk, and again the next day, the 15th. Boers had managed to get near the summit in front of the Yorkshire’s position, inflicting heavy casualties.

The 1st Contingent’s commander of No.2 Company, Capt William Robarts Napier Madocks (later Brigadier-General) seeing the situation was desperate called for a charge. Together with Lt. JG Hughes (promoted from Sgt just 16 days before), Sgt SW Gourley and four troopers (one of whom was Tpr George Mitchell) plus a L/Cpl from the Yorkshire Regiment, Madocks ordered the men to fix bayonets and together they charged over the brow of a corner of the hill, their unbridled aggression forcing the attackers to turn and flee. Before the NZer’s had gone barely 10 meters, they came under Boer covering fire. Reinforcements were sent to help them while supporting fire from a British artillery battery and Maxim gun opened up on the Boer’s horse positions. This greatly assisted the New Zealanders and the Yorkshire Regiment to recover the situation but not before a Trooper was killed and the Sergeant mortally wounded, he died of his wounds two days later. The action was subsequently reported in a despatch from the Brigade Commander, cavalry officer Lt-Gen John French (1852-1925).

COLESBERG – December 15, 1899, to January 25, 1900

From Lt-General French’s despatch, 2nd February 1900:

New Zealand Mounted Rifles – “On January 15, in the Boer attack on Slingers Farm, which was held by one company Yorkshire Regt, and one company New Zealand Mounted Rifles, Captain Orr, Yorkshire Regiment, who was in command, was badly wounded, and the Sergeant Major killed. Captain William R. N. Madocks, RA (a British officer attached to the NZMR), seeing the Yorkshire’s situation was critical, and practically without a leader; with the greatest promptitude he took a few of his men to the west side of the hill, and rallied the troops holding it; he caused them to line their entrenchments and stem the enemy’s advance; he then jumped up, gave the order to fix bayonets, and charged down the hill, upon which the Boers immediately turned; the greatest credit is due to Captain Madocks and his New Zealanders for their prompt action.”

“..a few of his men..” were New Zealanders: 2Lt. JG Hughes (awarded a DSO for this action; later a Lt.Col and commander of the Canterbury Regiment at Gallipoli), #104 Sgt SW Gourley (DoW) and Troopers #119 Aitken-Connell (KIA), #160 Mitchell, #12 Dickinson, #189 Wright and an un-named L/Cpl from the Yorkshire Regiment.

“Mention in Despatches” – Whilst Capt Madocks was cited by name in General French’s despatch, it is a debatable point whether or not 2Lt Hughes and the five NZMR Troopers and Yorks L/Cpl should also were able to claim some of the “greatest credit” of the “mention” made of their Company Commander, there being only the seven identified men who had fixed bayonets and charged, putting their Boer attackers to flight? Pre-First World War “mentions” were not always specified by name.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

Note: ** #44 Farrier George Roland BRADFORD of Paeroa (born Sussex, Eng), ex-Coldstream Guards; former Colour-Sgt Ohinimuri Rifle Volunteers; former Battalion Sgt-Major of 2nd Battalion (Hauraki) Infantry Volunteers; Trooper of No.1 Company – 1st Contingent NZMR had the unfortunate distinction of being the first NZ soldier to be killed in action or die from wounds in any conflict on foreign soil. He was mortally wounded at Jasfontein Farm on 18 December 1899. Struck by a bullet that penetrated above his hip causing him to fall from his horse and also strike his head, Bradford appearing to be dead, had been left as it was too dangerous to recover him. He was taken by the Boers to one of their hospitals where he died two days later on the 28 Dec 1899 – see also Bradford Bandolier below.

Battling the elements

The Boers had the distinct advantage of knowing the land well and how to use it to their advantage. the Contingent was fighting its first guerrilla war and had much to learn in this regard however, they adapted very quickly and overcame deficiencies with innovation and ‘Kiwi cunning.’ On 15 February, having fought off this resistance, Gen. French’s column was able to relieve the siege of Kimberley. Finally at Paardeburg, the Boer General Cronje was trapped and captured by French’s men.

Three weeks rest was promised but disease being a frequent ‘visitor’ interrupted this hard earned privilege for many of the Contingent. Being the wet season the greatest threat to the Contingent was the proliferation of Enteric Fever (Typhoid). On occasions the Contingent camps would be suddenly flooded during sudden downpours in the night. The wet followed by the heat of the day rapidly bred the disease carrying mosquito which resulted in widespread Enteric. Many had succumbed permanently to the ravages of Enteric. Oddly enough these circumstances had also created opportunities for unexpected promotion. Those who had shown sound initiative, courage and leadership qualities were promoted as the existing NCOs were hospitalised or invalided back to NZ. George Mitchell was one such beneficiary however his promotion to Sergeant was short lived. While camped at Bloomfontein a shortage of water caused by Boers controlling the dams supplying water to the town had forced the British to take water from unclean pools and polluted wells. This quickly resulted in rampant Enteric with up to 50 men from the column dying daily. NZ losses from bullet and shell wounds plus non-combat related injuries and sickness had all taken their toll on the 1st Contingent to this point, but remained manageable.

On 30 March whilst at Springfontein, Sgt Mitchell contracted Enteric Fever and Pleurisy. He was evacuated to the Kimberley Hospital and then via horse-drawn ambulance and train all the way back to Capetown. As a consequence he was required to relinquish his temporary Sgt’s rank and reverted to Trooper. He was hospitalised for the next four months before being re-assessed by a Medical Board on August 16th. Whilst making steady progress in his recovery, the decision was made to invalid him home.

The sick being invalided home were a mix of Australian and New Zealanders. On 21 October the steamer SS Wilcannia left Capetown for Australia, stopping at Brisbane and then Sydney where George and the other NZ sick were off-loaded. The NZers were re-embarked on the SS Mokoia and arrived in Wellington on 23 September at 1900 hours. The following day an Army Medical Board conducted assessments of the sick to determine what on-going treatment was required. George was convalescing quite well by this time and put on three months sick leave with full pay. He was officially discharged from the 1st Contingent NZMR with effect from his sailing date from Capetown, 21 October 1900.

Trooper Mitchell returned to Port Chalmers on the coastal steamer Flora a week later and spent the next few months at home in Balclutha taking it easy and reflecting on his time in South Africa.

Awards: Queen’s South Africa Medal, with Clasps: Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg, Driefontein, Transvaal

Service Overseas: 337 days

Dismounting the Contingent

The 1st Contingent of New Zealand Mounted Riflemen had left Capetown aboard two ships, the SS Harleck Castle on 4 November 1900 and the SS Orient on 13 December, ten weeks after George had departed. Those on the Harleck Castle were disembarked at Sydney and re-embarked on the SS Orient once it arrived. The Orient went first to Brisbane and then to Bluff before finally reaching Wellington on 21 January 1901.

During the voyage the 1st New Zealand Mounted Rifles Assn was founded aboard Her Majesty’s Troopship SS Orient (HMT 62) on 22 Jan 1901. Its raison d’etre was to keep the Contingent members in touch with each other, thereby promoting the bond of camaraderie and friendship they had forged together while in South Africa. An annual reunion and dinner was planned for the 21st of October (the date the 1st Contingent sailed) , the first being held in the Club Hotel Wellington in 1901.

The South African War Veterans Association (SAWVA) was established in 1920 to which all members of the ten NZ contingents as well as other colonial and Imperial unit members could join. The President’s Badge of office, known as The Bradford Bandolier,** was presented to the NZ Army Memorial Museum at Waiouru after the Association was disbanded in 1980. In July 1981 the last New Zealand Boer War veteran died – George Albert Tuck, born in Cambridge on 13th February 1884.

Note: ** Badge of Office. This bandolier was chosen as the badge of office for the SAWVA’s incumbent Dominion President in memory of its owner, #44 Trooper George Bradford (1st Contingent), NZ’s first battle casualty on foreign soil. The Bradford Bandolier was worn as a ceremonial accoutrement (see below) on all formal occasions and at Reunions. This pattern 1896 leather ammunition bandolier was in use from 1920 to 1980. It holds 38 silver plated ·303 bullets engraved with the names and tenure in office of each President of the SAWVA (including Lt-Col George Mitchell).

By 1970 there were 150 members remaining; the SAWVA held their final reunion at Palmerston North in 1974, being the same venue of the first Boer War Soldiers reunion more than 70 years before. There were still 60 members but only 12 (all in their nineties) could make the reunion. In 1980 with only four veterans still alive, two of them over 100 years of age, the South African War Veterans’ Association was wound up.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

The 1st Contingent NZMR had acquitted itself well and drew high praise from the Imperial command with the following awards being made to members of the contingent: Apart from awards to the senior officers, awards made to the men included – Queen’s Scarf** (#96 Tpr H.D. Coutts), Distinguished Conduct Medal (#3 Sjt-Maj W.T. Burr) and 11 soldiers were “Mentioned in Despatches.”

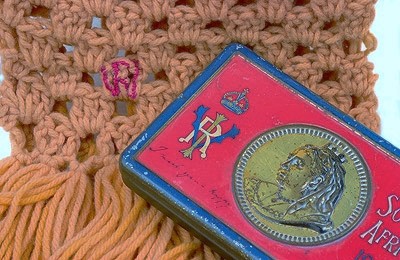

Note: ** The Queen’s Scarf was a uniquely special award for Bravery created by Queen Victoria. As a personal gift of appreciation for the bravery of the men who fought for Empire, the Queen personally crocheted and monogrammed eight fawn coloured woollen scarves monogram with the Royal Cypher V R in red. These she made for presentation to NCOs and soldiers, four Imperial and four Colonial soldiers (one each to Canadian, Australian, South African and New Zealander).

Lord Roberts wrote on 1 March 1902 that “his Lordship (Roberts) desires to place on record that in April 1900, her late Majesty Queen Victoria was graciously pleased to send him four woollen scarves worked by herself, for distribution to the four most distinguished private soldiers in the Colonial Forces of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, then serving under [my] command. The selection for these gifts of honour was made by the officers commanding the Contingents concerned, it being understood that gallant conduct in the field was to be considered the primary qualification”

Nominees were initially selected by their peers as being the most deserving of this Queen’s accolade, their recommendations being endorsed and forwarded by company commanders for the Commanding Officer’s decision. With the Scarf came a Gold Star with clasp (ordered by King Edward VII). The Scarf presented to Canterbury born Trooper Henry Donald Coutts of No.1 Company, 1st Contingent NZMR, is in the NZ Army Memorial Museum.

What next ?

George Mitchell made a full recovery and took a job at Waipahi as a Ploughman (teamster) in order to build up his strength and fitness. He still had South Africa on his mind according to his file, as he apparently had made inquiries returning to South Africa with an Australian Contingent for which he was accepted. He had even obtained a written endorsement from the Balclutha doctor who found him to be “…. quite recovered and in the best of health – 23 Nov 1900.” As was required, he informed his superiors. For some reason he did not go with the Australians, remaining in Balclutha to assist his father and brothers with their painting work. He also returned to the Clutha Mounted Rifles, attending parades and training camps as available.

Once more into the breach …

In a letter dated the 8th of March 1901, George wrote to the then Defence Minister (and Premier of NZ), the Hon. Richard J. Seddon, imploring him to be considered for an officer’s commission and to return to South Africa with the 7th Contingent. His Commanding Officer endorsed his request siting George’s suitability for comissioning and his record from the 1st Contingent. A number of the 1st Contingent NCO’s and men had already been commissioned and were short listed for return to South Africa with a subsequent contingent. There is no evidence on George’s files that his request was not approved but the 7th Contingent went without him.

In December 1901, the NZ Government offered Britain an 8th Contingent of 1000 men, which was immediately accepted. George’s bid for a second tour of duty was finally approved – he would go with the 8th Contingent due to depart in Feb 1902.

SA-5873 Regimental QM-Sjt George Mitchell – ‘G’ Squadron, South Island (SI) Regiment, 8th Contingent NZMR

Given a new regimental number and rank, George Mitchell (25) was appointed the Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant (Regt. QM-Sjt, or RQMS) for the Contingent which was made up of two Regiments, each with four Squadrons: the North Island Regiment (A, B, C and D Squadrons) and the South Island Regiment (E, F, G, and H Squadrons).

RQMS Mitchell embarked on the troopship SS Cornwall at Lyttelton with ‘G’ Squadron, South Island (SI) Regiment. The North Island (NI) Regiment aboard the SS Surrey departed from Auckland. Both ships convoyed to the Western Australian port of Albany on 8 Feb 1902 and thereafter arrived at Durban, South Africa on 19 March. The Regiments entrained separately to Newcastle in northern Natal, linking up on 21 March. On 3 April the Contingent trekked into the Drakensburg Ranges. While the British forces were implementing a huge drive beyond the mountains in north eastern Orange Free State, the 8th Contingent was tasked to guard the vacated Blockhouses and intercept Boers. None broke through their line.

Machavie disaster – 12 April,1900

Two Squadrons of the SI Regiment had been sent into the OFS to search for Boers in the Klip River valley. Whilst Boers were seen they were not engaged. After capturing some stock the Squadrons returned to Newcastle and entrained for Elansfontein, taking the branch line towards Klerksdorp. On 12 April upon receiving the ‘all clear’ to proceed from the Stationmaster of Machavie Station near Potchefstroom in the Transvaal. The troop train went through the station and commenced to descend a gentle incline. As it rounded a blind bend it smashed into an empty goods train sitting stationary on the tracks. Ten wagons carrying ‘E’ and ‘H’ Squadrons were smashed to pieces as other wagons were telescoped into those in front, while others jack-knifed or derailed and overturned. All of the men in the front truck had been killed while others were crushed in the wreckage. RQMS Mitchell’s ‘H’ Squadron had lost 16 of its men killed and 13 wounded. Some of the lucky ones had fortunately been sitting on the edge of the open trucks, saw what was about to happen seconds before impact and were able to jump from the trucks. Many more however had been lying in the bottom of the wagons and did not fare so well.

A military funeral for the victims was held at the Klerksdorp Cemetery. It was very well represented by 200 Canadians, 600 Australians, 900 men from various regiments stationed near Machavie, detachments from the Seaforth, Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders and Royal Artillery, 700 Boer refugees as well as members of the 8th Contingent.

Ironically, the 12th of April was also the date on which peace negotiations at Vereeniging in the Transvaal commenced, despite the fact that some Boer leaders were continuing to attack British columns. Following the funeral, the 8th Contingent remained at Klerksdorp until 22 April before taking part in the last drive west towards the Kimberley-Mafeking railway. The column, commanded by General Ian Hamilton, had great success during the drive over the following month during which they netted 367 Boer POWs, 3260 head of cattle, 326 horses, 200 sheep, 106 trekking oxen, 95 mules, 175 wagons, 66 Cape carts, and about 7000 rounds of rifle ammunition. Their efforts drew high praise from Lord Kitchener no less.

In his capacity as the 8th Contingent’s RQMS, Mitchell’s good work had been noted by the Contingent commander, Lt-Col R.H. Davies, to whom the RQMS reported. In his Contingent Report to General Hamilton prior to departing South Africa, Lt-Col Davies highlighted the RQMS’s tireless efforts in keeping the Contingent well supplied under difficult circumstances. As a result, RQMS George Mitchell was among the roll of those “mentioned” by name in Lord Kitchener’s Final Despatch of 23 June 1902, and subsequently published in the London Gazette.

Homeward bound

On 4 July 1902, the 8th Contingent embarked on the SS Britannic for their return to NZ, via Sydney to drop off Victorian soldiers. The voyage was highly controversial with allegations of overcrowding and men being ill-fed, the hospital full of sick men, and deaths from a measles outbreak levelled against the shipping company on their arrival in Wellington on the 1st of August. RQMS Mitchell was lucky not to become one of the dead himself having contracted Bronchitis since boarding Britannic and spending the entire voyage in the ship’s hospital.

When Britannic reached Australia, the sick were transferred ashore and hospitalised awaiting another vessel. Following Britannic’s arrival with the South Island Regiment at Lyttelton on 5 July, the 8th Contingent was disbanded on 13 August 1902. Clearly the soldier’s complaints regarding the state of Britannic had foundation. The ship underwent an inspection in October 1902 after she had reached the Belfast shipyards. As a result she was condemned for scrap and broken up in 1903!

A Medical Board was convened in Dunedin on 25 Aug from which George Mitchell was given two months of outpatient sick leave (at home) on full pay.

Awards: Mentioned in Despatches (Kitchener, 1902); Clasp for Queen’s South Africa Medal – Transvaal

Service overseas: 146 days

Citation for MENTION in DESPATCHES

SA-5873 Regt Q.M.-Sgt George Mitchell – 8th Contingent, NZ Mounted Rifles

Mentioned in Lord Kitchener’s Final Despatch, 23 June 1902 – “For loyal service”– London Gazette, 29 July 1902, p29

In due course George re-joined his two brothers, William and Walter, in the contract painting work. George Mitchell Snr was now the proprietor of store in Balclutha that supplied all manner of paint and decorating supplies. Whilst the work for George was necessary for income, when compared with the action he had been part of during his service with the two contingents in South Africa, it must have seemed to him to be about as stimulating as ‘watching paint dry.’ During his time back in Balclutha, George maintained his commitment to the Volunteer Corps and was holding the rank of Colour Sergeant. Having spent almost four and a half years with the CMR, George’s work circumstances meaning he would have to transfer out of the CMR as he was no longer living in the Clutha district. He had secured a position managing a wholesale company in Invercargill for a Mr Andrew Rees and accordingly, transferred to the Otago Rifle Volunteers on 30 October 1902 with the rank of Colour Sergeant.

In January 1904 George (27) married Balclutha born Alice Mary BAIN (1875-1923) in Dunedin, the couple making their home initially in Tay Street, Invercargill. George and Alice started a family, their first four children all born before the outbreak of the First World War. The eldest was Alan Cunningham MITCHELL (1904–1940) who was followed by Alexander George MITCHELL (1906–1978), Alice Muriel MITCHELL (1909–1944) and John Garfield MITCHELL (1913–1978).

With his active service background and being well reported, Colour Sergeant Mitchell did not have to wait long before he was commissioned. In 1904 he was made a Lieutenant, promoted to Captain in March 1907, and appointed Adjutant of the 4th Battalion, Otago Rifle Volunteers in Aug 1908 (name changed to 14th (South Otago) Rifles in 1911, the year the territorial military volunteers in New Zealand were reorganised as the NZ Territorial Force). On 30 Oct 1909 Capt. Mitchell was promoted to Major, transferred to the 8th (Southland) Rifles of which he became the Regiment’s Second in Command.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

First World War

The Empire’s loyal member nations willingly contributed military support for the Imperial forces to fight Germany and accordingly, the NZ Government committed a Division (approx 8500 men and 3000 horses).

Major Mitchell was mobilised for overseas service in October 1914, following the unopposed capture of German Samoa by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) Advance Party on 29 August. After missing selection for the Main Body, a glowing endorsement from his CO to a fellow officer ‘in high places’ ensured George’s previous service and subsequent achievements in the Territorial Force were not overlooked. Selected for the 2nd Reinforcements, Major Mitchell was, unusually, permitted to retain his rank.** He was promptly promoted to substantive Major on 21 Nov 1914 and given command of the 10th (North Otago) Company, one of four Otago and Southland companies that together formed the Otago Infantry Battalion (OIB). Prior to his departure, Major Mitchell was also awarded the NZ Long and Efficient Service Medal for the completion of 16 years of efficient service in the Volunteers and Territorial Force.

George bid his wife Alice and the children farewell in early December and embarked his 10th (North Otago) Company at Port Chalmers, together with the other three companies of the Otago Battalion – 4th (Otago), 8th (Southland) and 14th (South Otago). Their ship proceeded to Wellington and joined with the remainder of the ten ship convoy carrying the NZEF’s Main Body. The convoy left Wellington with an escort of warships on 14 December and sailed to Albany to join with the Australian component of troopships. Together, the ANZAC convoy with its enhanced armed escort proceeded towards South Africa, the first stop on route to England.

Note: ** It was normal practice for territorial personnel to relinquish their rank upon enlistment with the NZEF as they were generally not as experienced or professionally qualified at that rank level, to the level required of their career soldier counterparts. George Mitchell’s retention of his territorial rank says much about the confidence his superiors placed in his ability to lead men in battle. Their selection of Major Mitchell to lead the 10th (North Otago) Company was a decision he would soon prove was well found.

Egypt and the Canal

As we now know, the ANZAC convoy was re-directed to Egypt mid-voyage when Turkey declared its allegiance to the German Kaiser and so entered the war. The NZEF landed at Alexandria on 3 December and established the NZEF camp at Zeitoun, north of Cairo. After almost two months in Egypt, on 26 January 1915 the Regiment was ordered north to Kubri, to help form a defensive line against an expect Ottoman Empire attack on the Suez Canal, a most vital shipping access point to the Mediterranean Sea. The line was on the eastern side of the canal and extended between the Little Bitter Lake in the North and Suez in the South. Here they combined with the already stationed Indian troops. The attack came on 3 February and was repulsed whilst the Otago Battalion was kept in reserve. On 13 Feb 1915 after 10 days of intermittent fighting, Private William Ham (from Ngatimoti, near Motueka) was severely wounded and died two days later, thus becoming the NZEF’s first combat fatality of the war.

Dardanelles – Gallipoli

The Regiment began preparing for the invasion of Gallipoli in early April 1915. Their training was focused on strength for the broken and steep terrain they would encounter. At this point the Regiment (then still named the Otago Infantry Battalion) had four companies, 4th (Otago), 8th (Southland), 10th (North Otago) and 14th (South Otago). On 10 April they departed Alexandria on the Annaberg, a captured enemy ship that was ‘filthy beyond description, and abominably louse-ridden’. Three days later they arrived at Mudros in the Greek Islands, the staging area of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

On 25 April between 2:30 and 4 p.m. the Otago Battalion troops disembarked from their boats at Gallipoli. This was after a significant gap in the landings from the rest of the invasion which had occurred before 10 a.m. that morning. The Battalion was ordered first to cover the left flank and then to Plugge’s Plateau where initial progress from the morning’s landings had become bogged down. The Battalion was disorganized and was not incorporated into the broken front line as a single unit. Heavy fighting occurred until early the next morning. During this time several Ottoman counterattacks occurred but the Regiment held its ground, despite being without effective artillery support.

The next morning brought a considerable Ottoman artillery barrage, which could now be returned by two New Zealand guns and supporting naval vessels. The 10th Company of the Battalion was sent to Steel’s Post for two days of heavy fighting to aid the Australians already there. The evening of the second day was relatively quiet along the rest of the Otago Battalion line. The invasion force had a secure beachhead, but had failed to reach their planned targets or capture the heights around the landing site.

Failed offensive

It involved New Zealand and Australian troops, with the British in reserve. The Otago Battalion was to advance about 400 m along the ridge near Knoll 700, flanked by the Canterbury Battalion. A limited offensive was initiated on the evening of 2 May to capture the much-contested Ottoman salient running between Pope’s Hill and Quinn’s Post (later to be called Dead Man’s Ridge due to the numerous friendly forces casualties that occurred in the attack).

It was during this night attack that Major Mitchell sustained the first of two wounds** while he was on Gallipoli. During the night attack Major Mitchell sustained badly broken ribs after a heavy fall into an unseen trench. Despite being heavily bandaged and in great pain, Major Mitchell continued to work with his men in the days and weeks following the attack, whilst preparing for an even more significant one the ANZACs were planning for August. When the time came, still bandaged and in substantial pain, Major Mitchell led his troops in the advance up towards Chunuk Bair on 6-7 August, 1915.

Of Mitchell and the attack, a colleague, Lt-Col Athelstan Moore wrote: “Major George Mitchell, of Invercargill, who is now badly wounded, is an awfully good fellow. He has pluck—any amount—but he has also grit. You know he wasn’t wounded the first time – he fell and broke some ribs—not in front, but right round at the back, near the spine. When he came back he was still bent sideways, and had to be bandaged up awfully tightly. Well, on the night of August 6-7 he fainted twice during the Advance—from exhaustion, or, for what we know, pain. I was too busy to take any notice of him. More hills had to be taken and incidentally, 200 prisoners—all this very exhausting work. I was not too busy to see Mitchell leading his men in a most brilliant charge in the grey dawn, and yet he must have been “done” to the world. There must be an awful lot of go in a man like that.”

Note: ** Wounds – the recording of wounds was a vague art during WW1, often made by unqualified or untrained clerks/recorders. Any significant injury was recorded as a “Wound” if it was sustained when in contact with the enemy. A soldier’s military file may have, for instance, “GSW” which was used to describe a “Gunshot Wound” could also mean a “(Artillery) Shell (shrapnel/blast effects Wound”, or it could be used for a soldier who was affected by and required treatment for being Gassed. Sometimes “SW” on its own was used which could mean either “Shell Wound” or “Shrapnel Wound” – there was little difference. Most file annotations of this type were non-specific unless explained by accompanying details of the injury, e.g. “GSW – shell splinters entered back and R thigh”.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

For his personal courage and fortitude in this attack, Mitchell drew widespread admiration from his fellow officers when they learned of his circumstances in harbouring (concealing?) a serious injury whilst inspiring his men in the attack, an injury that would still have been painful. Even more pain was inflicted during the attack. Major Mitchell was wounded a second time with a serious gun-shot wound to his left foot. Unable to walk, he was evacuated from Gallipoli within hours to a waiting Hospital Ship off-shore and returned to Alexandria, Egypt with a full shipload of casualties two days later. Admitted to the Deaconess Hospital on 9 June, following treatment he was returned to the NZ Base Depot in France on 4 July 1915. In September, further surgery was warranted on his foot in England. He was admitted to the Endsleigh Palace Military Hospital, formerly the Endsleigh Palace Hotel in London, one of many hotels co-opted as WW1 military hospital facilities. Recovery and convalescence was undertaken at “Grey Towers” aka, NZ Convalescent Camp at Hornchurch in Essex over Christmas 1915. His recovery however from the foot wound had left Major Mitchell with a permanent limp, earning him the enduring nick-name of “Hoppy” Mitchell.

“Hoppy” goes west…

The Otago Battalion/Regiment was involved in fighting on the Western Front from 1916–1918. Before moving to France it was reorganized and comprised the 1st and 2nd Battalions (the Otago Infantry Regiment – OIR) as part of the newly formed New Zealand Division. The 1st Battalion was part of the Division’s 1st Infantry Brigade and the 2nd Battalion was part of the 2nd Infantry Brigade, effectively splitting the Otago Infantry Regiment in two.

Discharged from “Grey Towers” in March 1916, Major Mitchell returned to the NZEF Depot at Sling Camp on the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire where he was attached to the NZ Reserve Group. A month spent with the 1st Infantry Brigade Training Battalion was followed by another month in temporary command of the 2nd Infantry Brigade Training Battalion at Sling, ahead of his return to France. On 10 Oct 1916, Major Mitchell was appointed a Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel and Officer Commanding of the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion which was made up of soldiers from the Auckland and Wellington Infantry Regiments.

In January 1917, T/Lt-Col Mitchell received notice of his posting back to France. He also learned of a European decoration he was to be awarded from the King of Serbia, for his leadership at Gallipoli and subsequently. T/Lt-Col Mitchell was to be made an Officer of the Serbian Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords which was gazetted in February.

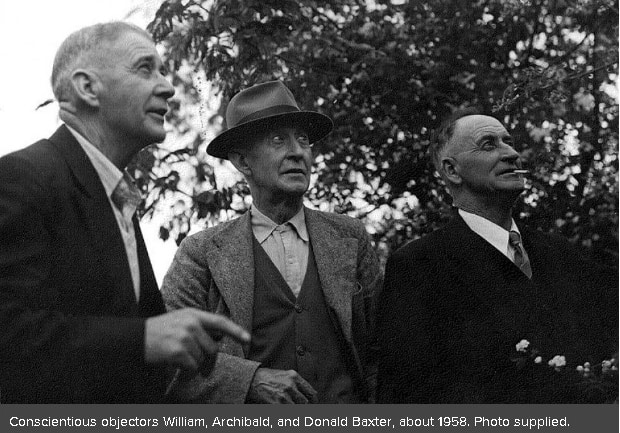

In Feb 1917, T/Lt-Col Mitchell relinquished his 3rd Reserve Bn appointment to take up the appointment of Officer Commanding of the NZ Infantry and General Reserve Depot (NZR & IGD) at the Base Depot Camp, Etaples. He would have direct command over all New Zealanders entering or leaving France who passed through the Etaples Depot (which most did), some 5000 NZers at any one time – these included the ‘conchies’ – some 14 New Zealand Conscientious Objectors who had broken the law by refusing to undertake military service as was required of them under the country’s Emergency Regulations. Those who refused on the grounds of religious, pacifist or other beliefs, were imprisoned in NZ. Those who warranted greater persuasion or who had ‘bucked the system’ ** in NZ were sent to France as punishment for their resistance antics, the most resistant or rebellious ending up in the Front Line. It just so happened that Lt.Col Mitchell would strike four of the most infamous of the 14, the ringleader being one Archibald McColl Learmond Baxter (1881–1970).

Note: ** Executions – Also during this time, three of the Otago Regiment’s soldiers were executed: John Sweeney (37), 1st Otago Bn on 2 Oct 1916 for Desertion; Jack Braithwaite (31), 2nd Otago Bn on 29 Oct 1916 for Mutiny; Victor Spencer (23), 1st Otago Bn on 24 Feb 1918 for Desertion. They were all pardoned 93 years later.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

Citation for ORDER of the STAR of KARAGEORGE with SWORDS, 4th Class

Full Title – “Officer of the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords”

8/1173 Major George Mitchell – 1st Battalion, Otago Infantry Regiment – N.Z.E.F.

– “For distinguished service rendered during the campaign.” – London Gazette – 15 February 1917, p1608

Note: During the Great War, the Allied Countries (not including the High Command) such as France, Belgium, Russia, Serbia and Italy, exchanged numbers of Medals to be awarded to worthy recipients. The King of Serbia presented the following awards – the Order of the White Eagle, the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords (for officers), the Star of Karageorge with Swords (for NCOs) and the Obilich Medal for Bravery in gold (gilt) and silver.

The Order was generally awarded for acts of bravery on the battlefield. Recipients included both soldiers and civilians, though until 1906 only Serbian citizens were permitted to receive the award.

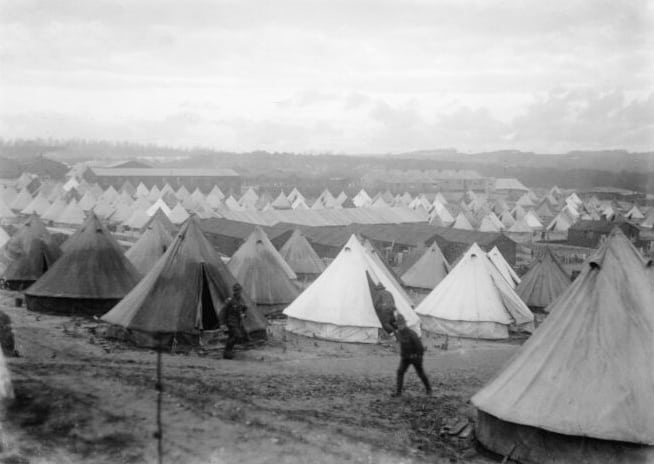

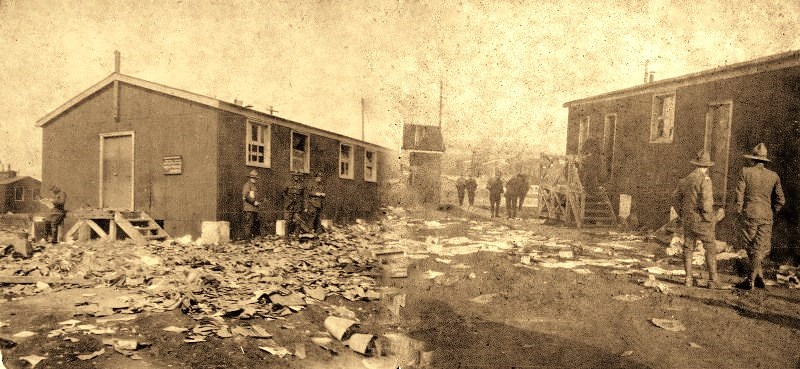

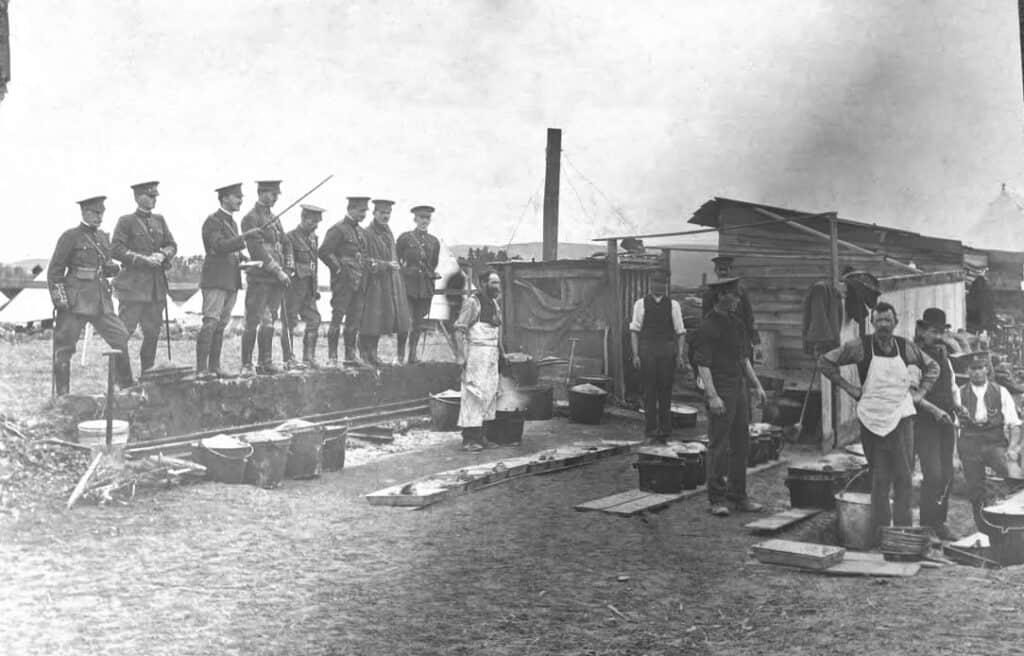

Etaples – the New Zealand Base Depot

The camp was a training base, a depot for supplies, a detention centre for prisoners, and a centre for the treatment of the sick and wounded, with almost twenty general hospitals. At its peak, the camp housed up to 100,000 people; altogether, its hospitals could treat 22,000 patients. With its vast conglomeration of the wounded, of prisoners, of soldiers training for battle, and of those simply waiting to return to the front, Étaples could appear a dark place. The camp was hated by the soldiers for a variety of reasons that Lt-Col Mitchell would soon become familiar with.

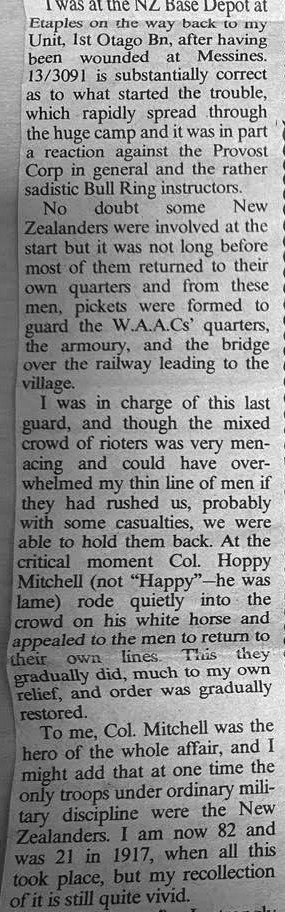

Once his rank was made substantive on 15 April 1917, Lt-Col Mitchell assumed full command of the NZI & RBD. While in command of the Depot Lt-Col Mitchell was faced with a couple of unforeseen but significant challenges. New Zealand soldiers were involved in a well reported mutiny** in Sep 1917. There are many conflicting opinions of this event but it would appear its genesis had been the ill-treatment of the soldiers by their instructors, restricted access to the local town and the heavy handedness of the British Military Police.

Arthur Whelan, a Sunday Star Times writer, publish the following in 2017 after interviewing one of Jock Healy’s descendants who had researched his part in the mutiny.

Whelan wrote “Kiwi bugler Arthur ‘Jock’ Healy never fired a shot in anger during World War I, and yet he still managed to start a mutiny that exposed the British Army’s inhumane treatment towards its own soldiers, and the men who had travelled halfway around the world to fight for the empire. One hundred years on, the uprising at the infamous training camp next to the fishing port of Etaples on the northern French coast, just south of Boulogne, remains the subject of censorship and speculation over what really went on.

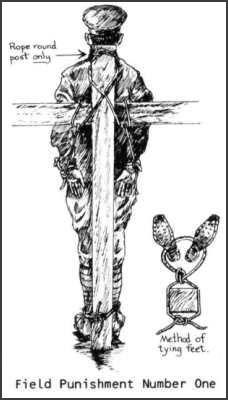

This army city was a brutal, hated place of route marches in the sand dunes, exposure to chlorine gas and endless bayonet drills. It was a place where “canaries” (instructors) and “redcaps” (military police) with safe jobs far behind the front lines could bully and torment even veterans of the trenches recovering from wounds. The slightest sign of dissent could result in field punishments that included a form of crucifixion against the wheel of a howitzer.

Respite from this hell of bullying and boredom involved a surreptitious journey across the estuary into the town of Etaples and the seaside resort of Le Touquet and back before the tide came in. At 3pm on the Sunday afternoon of September 9, 1917, Arthur “Jock” Healy, a wheelwright from Blenheim who had enlisted in the New Zealand Rifle Brigade a year earlier, found himself stranded by the rising River Canche. He had no choice but to return to camp over the Three Arch Bridge, where the military police were waiting. The routine beating that followed was trivial by Etaples standards, and thousands of soldiers had endured this regime resentfully but silently. However, this day would be different, and it was the Kiwis who finally rose up.

An enraged group of Healy’s New Zealand comrades descended on the police hut. A crowd started to gather and the mood turned ugly. The Kiwis had thrown a match on an enormous dry pyre of resentment. Stones were thrown, scuffles broke out, shots were fired at the crowd. And then the redcaps ran for their lives, and those not fast enough were pulverised.

Etaples entered a kind of twilight state in the days after Healy’s arrest. …. Armed Australians went out into the sand dunes hunting for Canaries – so-named for their yellow armbands. Elsewhere, British soldiers marched to the Bull Ring as ordered, but then just sat down in a silent strike. Soldiers were ordered to block the bridge out of the camp; but the troops laughingly formed scrum-like formations and swept them aside, heading out to cause mayhem. And then, almost all of them returned. In the end, of the thousands of troops who went out either for revenge or a drink, just 23 never came back.

Of course, the good times were never going to last. …. The Battle of Passchendaele was raging, and the dithering British high command eventually restored order, with the help of machine guns trained on the parade ground. More than 50 soldiers were court-martialed; one was shot. However, the brief outbreak did achieve a victory of sorts. The hated Bull Ring was abandoned; soldiers were allowed to swim in the sea and go into Etaples for tea and chips. ….

Of all the millions of men who passed through Etaples, why did the mutiny start with the Kiwis? In one of the few scholarly articles on the episode, published in the Oxford University Press journal Past & Present in November 1975, historians Douglas Gill and Gloden Dallas speculated that Anzac troops were “contemptuous of the narrow discipline to which British troops subscribed, and were led by officers who had invariably first shown their qualities as privates in the ranks”. In France, the men from Down Under – “a band of adventurers, all volunteers who had travelled across the world” – were the “bane of authority” and constantly in trouble. …

Lt-Col Mitchell was credited with helping to restore order into the shemozzle. One of the veterans who wrote to the newspaper outlined an observation of Lt-Colonel Mitchell’s part …. see article at right.

As for Jock Healy, the Blenheim bugler who had merely been trying to sneak back into camp who inadvertently became the spark that enflammed his fellow soldiers to exact retribution on his behalf, faded into obscurity. He does not reappear in the witness accounts and recollections of Etaples. A week after the outbreak Healy was in hospital with influenza, part of a recurring pattern of serious illness during his overseas service. He retrained as a gunner but in the following April was diagnosed with a heart murmur and by June he was back in Blenheim, having never fired a shot in anger. In 1921 Jock married Martha, and they had five children – one of whom, Noel, served in the Italian campaign of World War II – and he lived out his days in Nelson, where he died in November 1966.

Arrival of the ‘Conchies’

It was into this volatile environment that recalcitrant Archie Baxter and his three cohorts Mark Briggs, Harry Patton and Lawrence Kirwin arrived in October 1917, and determined to continue their defiance. Six of the seven Baxter brothers (the seventh was married and therefore had a case for exemption) had refused to enlist and went to gaol for their beliefs. The most recalcitrant objectors were sent to France at the Minister of Defence, James Allen’s behest who believed objectors should forced to go to war.

Brigadier General G. S. Richardson, commandant of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in Britain, having a free hand to deal with the men, had ordered them sent to Etaples and wanted them confined, given field punishment and then sent with their units into the trenches even if they had to be carried on stretchers. Lt-Col Mitchell endeavoured to have the men comply but they remained defiant at every opportunity, refusing to walk, stand, salute or wear uniform. In consequence they were carried, dragged or transported in a hand-cart, and cajoled unsuccessfully to try to change their minds but staunch refusal and defiance made this a highly frustrating and impossible battle to win.

Some commentators maintain Mitchell held particular animosity toward Baxter. He certainly took a personal interest in Baxter’s case and some would say treated him with undue severity, but Mitchell was adamant discipline would be upheld and not undermined, besides, both the Defence Minister’s and General Richardson’s intent was very clear. As a consequence, Field Punishment No.1 was ordered: they were tied to a post in the open with their hands bound tightly behind their backs and their knees and feet bound for up to four hours a day in all weathers.

In January 1918 Lt-Col Mitchell completed his term as OC of the NZ Base Depot and returned to the 3rd Otago (Reserve) Battalion as OC. In addition, he was appointed Commanding Officer of the NZ Division’s Wing at the 22nd [XXII] Corps Reinforcements Camp at Abeele, of with the 3rd Otago was part.

NZ Entrenching Group, Abeele, France

The 22nd Corps Reinforcement Camp was the last stop for all reinforcement personnel going into the Front Line. In March Lt-Col Mitchell took concurrent command of the NZ Entrenching Group at Abeele which at this time was based in a wood at Pas-en-Artois, about 40 kms east of Abbeville. Whilst at Abeele, Lt-Col Mitchell was tasked again with managing Archibald Baxter and two of his defiant friends. The four had survived the Field Punishment No.1 and as a last resort to turn them, were ordered to be taken sent into the trenches. One of the men decided to comply while the continued resistance of the other three was the last straw. They were ordered to the trenches on the Front Line with Mitchell’s 2nd NZ Entrenching Battalion.

Baxter later wrote of his being beaten by less than empathetic NCOs and officers at the front, that they were sent to where shelling was heaviest, denied food and finally on 1 April 1918, being taken to hospital in Boulogne where he was diagnosed as having ‘mental weakness’ and ‘confusional insanity’ in his determination not to fight. Three weeks later a British medical board confirmed the diagnosis of insanity, although it suggested that this may have been exaggerated so that he could not be court-martialed by the New Zealand army. None the less, it was the end of Baxter’s war. He was taken to a British hospital for mentally disturbed soldiers, and sent home in August 1918, one of only two of the four (the other was Briggs) to hold out to the end.

Baxter’s subsequent writings hint at a commander (Mitchell) placed in an impossible position by the presence of the Objectors (there were several at Etaples during Mitchell’s time as commander) and the commander of the NZ Forces in England, Brigadier-General Sir George Richardson’s orders on how to deal with them. One of Baxter’s closest cohorts in their passive resistance, Mark Briggs said however, that he found Mitchell to be fair and reasonable.

Historian David Grant, in his 2008 book: “Field Punishment No.1”, also contended that Lt-Col Mitchell developed a grudging admiration for the two ‘conchies’. “Finally, Mitchell was the first to recognise that Baxter and Briggs’ utter determination not to be broken was because their objection was genuine – it was he who tried to persuade (General) Godley to have the torture against them stopped after their experiences at the front lines. Unlike the others, he came to know these men first hand, not as names on a sheet as was the case for Richardson and Godley.”

Note: ** Mutiny – this incident was the first of two, the second occurred in Dec 1918 and involved both NZ and Australian soldiers who rioted and destroyed camp facilities due to the inordinate delays and cancellations of repatriation ships, as well as the lack of information concerning return to NZ. Other riots had occurred at Etaples but involved mainly British troops, again disgruntled with their living conditions and delay of their return to their homes.

Towards Armistice

During the German’s 1918 Spring Offensive on the Western Front, Lt-Col Mitchell’s soldiers of the 2nd NZ Entrenching Battalion were in the thick of the fighting. At the Battle of the Lys in April 1918 more than 200 of his men were captured when they were exposed by a rapid and unannounced withdrawal by British forces. The Otago Regiment last saw action on 5 November 1918. Lt-Col Mitchell’s leadership and management of the Etaples riot and the unusual circumstances in managing the Conscientious Objectors sent to France, as well as his own unit, was acknowledged an honourable “Mention in Despatches.”

As the war wound down towards an Armistice which was finally signed on 11 November 1918, thus formerly bring the war to a conclusion and Lt-Col Mitchell’s tour of duty in France with the NZEF. George Mitchell had had much thrust upon him during his more than four and a half years at war. His demonstrated capability for work under pressure, tenacity and drive during difficult circumstances had greatly impressed his superiors. For his leadership, loyalty and commitment as both a field commander in battle, and the challenging circumstances at Etaples and beyond, Lt-Col Mitchell was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in January 1918.

On 29 October Lt-Col Mitchell relinquished his appointment with the Entrenching Group to attend training with a British Tank unit. The first use of tanks on the battlefield was the use of British Mark I tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (the opening battle of the Somme Offensive) on 15 September 1916, with mixed results. Many broke down, but nearly a third succeeded in breaking through. Thereafter the Allies sought to capitalise on their experience with these to see how they might be incorporated into their own warfare training and to develop plans for the use of tanks in the future. Mitchell returned one week after the Armistice had been declared and prepared for duty in London to furnish a report and discuss his findings. He was due in London by the end of December. In January, more problems with his left foot wound netted him another two weeks in hospital before being released to Sling Camp on 6th Feb.

Lt-Col Mitchell was appointed Officer Commanding Demobilized Troops for the repatriation voyage home to NZ. He departed England on 11 May aboard the SS Northumberland which arrived in Wellington on 25 July 1919. Following his own demobilisation, George Mitchell headed home to “The Retreat” at Waikiwi for some well earned post war service leave with his family.

Awards: DSO, 1914/15 Star, British War Medal, 1914-18, Victory Medal with MiD device

Citation for MENTION in DESPATCHES

8/1173 Lt-Colonel George Mitchell, OSK† – N.Z.E.F.

– Mentioned in Field Marshall D. (Douglas) Haig’s Despatch of 7 November 1917: “For distinguished and gallant services and devotion to duty during the period February 26th to midnight September 20-21st, 1917” – London Gazette: 28th December 1917, p13575

Citation for the DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER

8/1173 Lt-Colonel George Mitchell, DSO, OSK† – N.Z.E.F.

To be a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order – “For distinguished service in the field [France and Flanders]” – London Gazette: 1st January 1918, p29

Other: 2 x Wound Stripes (Gallipoli); ANZAC (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion, 1967

Service Overseas: 4 Years 146 days

Total NZEF Service: 4 Years 273 days

The green, green grass of home…

The return to civilian life and being home at “The Retreat” with Alice and his family was no doubt a joy to George but as most veterans in these circumstances tend to find, George found it difficult to settle. Whilst he had been away, apart from the birth of his daughter Georgina, George’s mother Sarah had also died suddenly at home in Balclutha in February 1917 at the age of 46. Sarah George had loved to garden and also kept a herd of dairy cows whose milk she sold to the town locals. At the time of her death Sarah was mother to 14 children and a grandmother to 25 grandchildren.

George’s father, at 63 years of age, remarried in 1919 to 62 year old Balclutha lady, Flora McLENNAN (1866-1948), a native of Monar in Rosshire, Sccotland. George and Flora remained in Balclutha for the rest of their days, George Snr passing away in October 1926 at the age of 75. Widow Flora lived on for another 22 years before passing away at the age of 82 in 1948. Both were buried in the Old Balclutha Cemetery.

Upon his return to New Zealand Lt-Col Mitchell was deemed to be officially discharge from the NZEF with effect from his arrival on the Northumberland, 25 July 1919, which also meant he was immediately transferred to the establishment of the 8th (Southland) Regiment’s Reserve of Officers with effect from Feb 1920. Until that time he could go home and take his accumulated post active-service leave, unless required to re-mobilisation should the need arise – I did not.

~~~~~~~~~~~~<>~~~~~~~~~~~~

To the Capital – 1919

Once settled in Karori, George wasted no time in re-connecting with his military colleagues. He had maintained his connections with the 8th Southland while in Wellington which led to his being offered a position on the establishment with the rank of Major, which he accepted. George remained on the establishment for another seven years until age required him to be mandatorilly placed on the Retired List of Officers in Oct 1927.

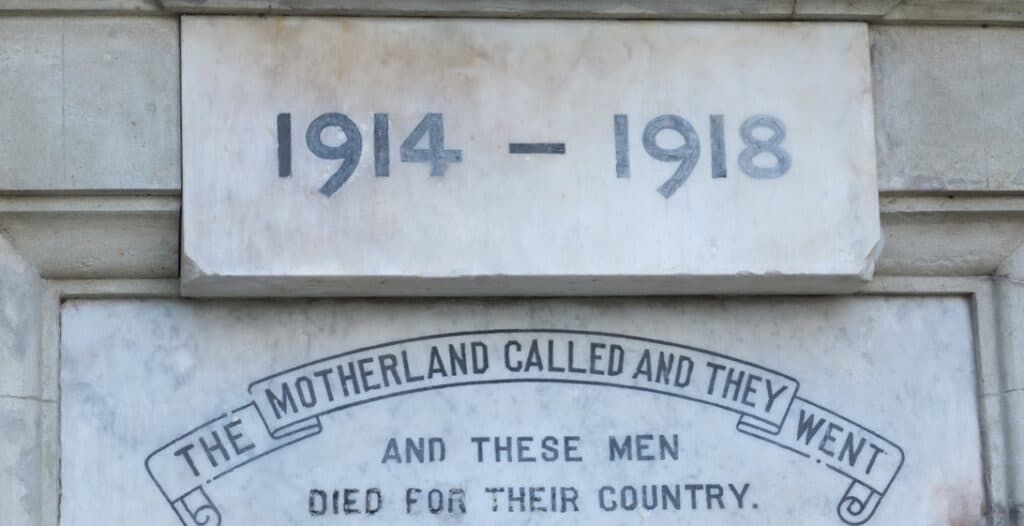

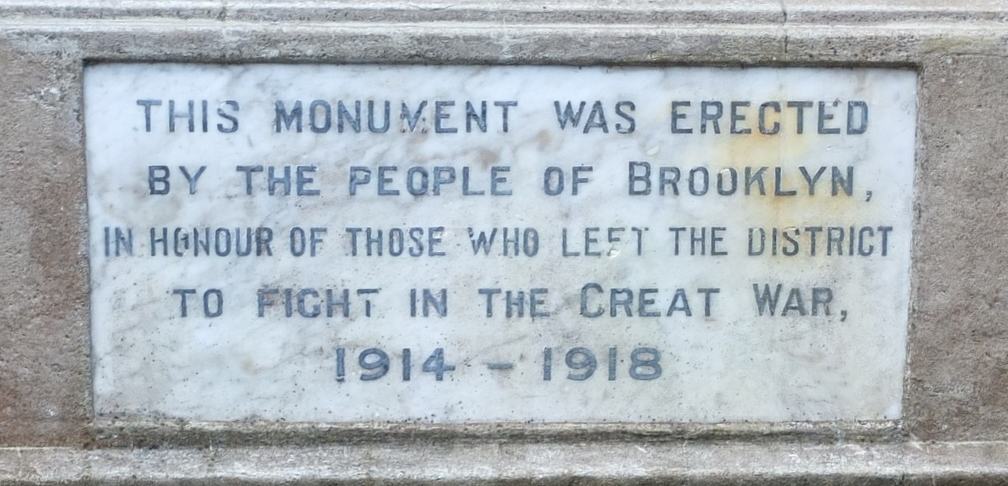

During his first year in Wellington, George’s future included a foray into political life. Capitalising on his war record and connections within the Defence Ministry, George was encouraged to enter the fickle world of politics as an Independent Liberal candidate, standing for the Parliamentary seat of Wellington South in 1919. He won the seat, defeating the sitting Labour MP in what was said to be the sensation of the election. The fact that his opponent was Bob Semple, a Conscientious Objector who was jailed during the war, must have been particularly satisfying given the tribulations he had had with Archie Baxter and co in France.

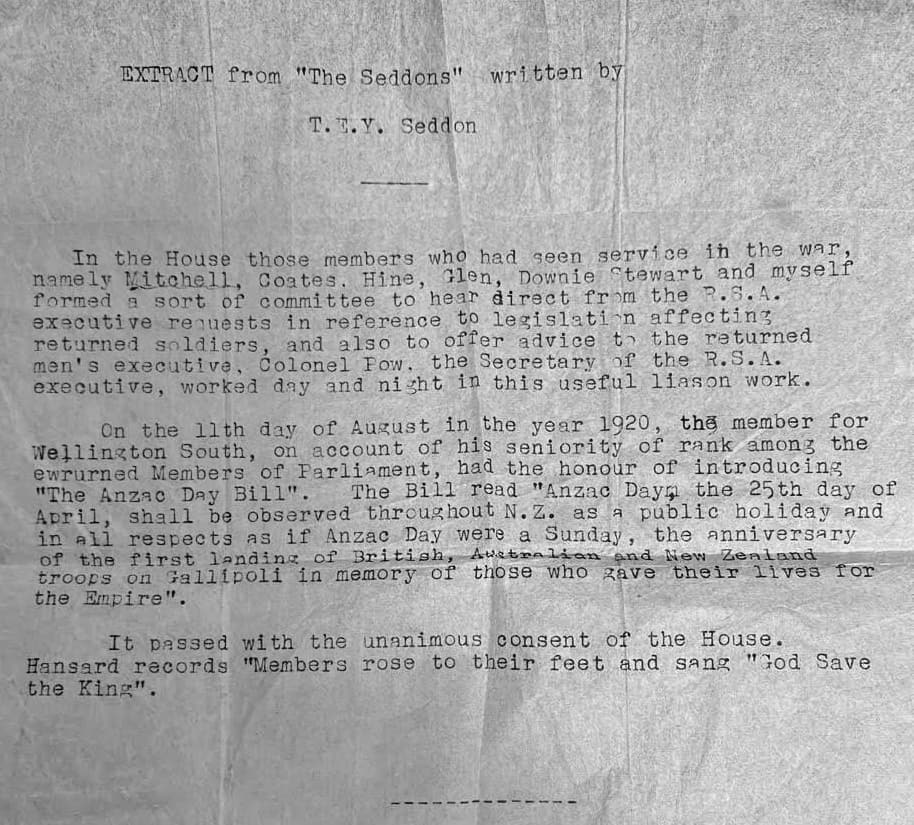

The “Anzac Day” Bill

The following year on the 11th of August 1920, George being the senior rank among the returned Members of Parliament, was given the honour of introducing the “Anzac Day Bill” which would see the day enshrined in New Zealand law as an official day of remembrance. The Bill read:

“Anzac Day, the 25th day of April, shall be observed throughout New Zealand as a public holiday

and in all respects as if Anzac Day were a Sunday, the anniversary of the first landing of British,

Australian and New Zealand troops on Gallipoli in memory of

those who gave their lives for the Empire.”

George held the Wellington South seat for only one term of government before being defeated at the 1922 general election. He was dealt an even bigger blow when less than a year later his wife Alice died suddenly in August 1923, aged 46.

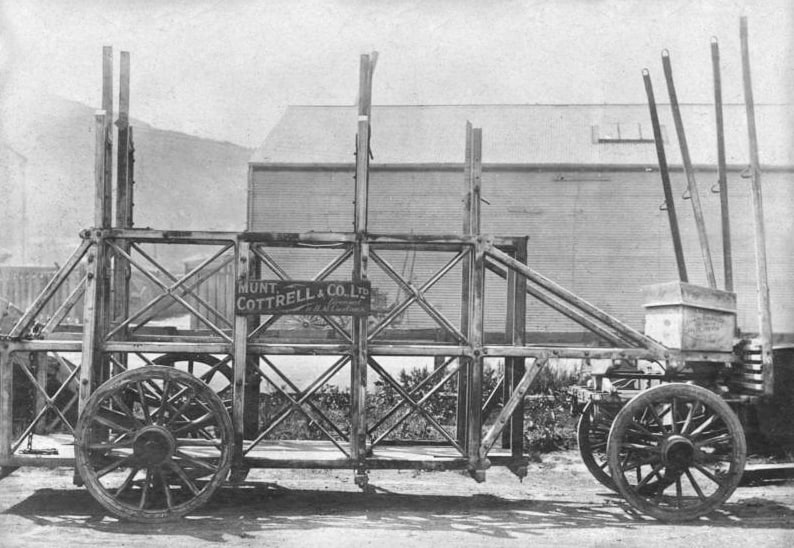

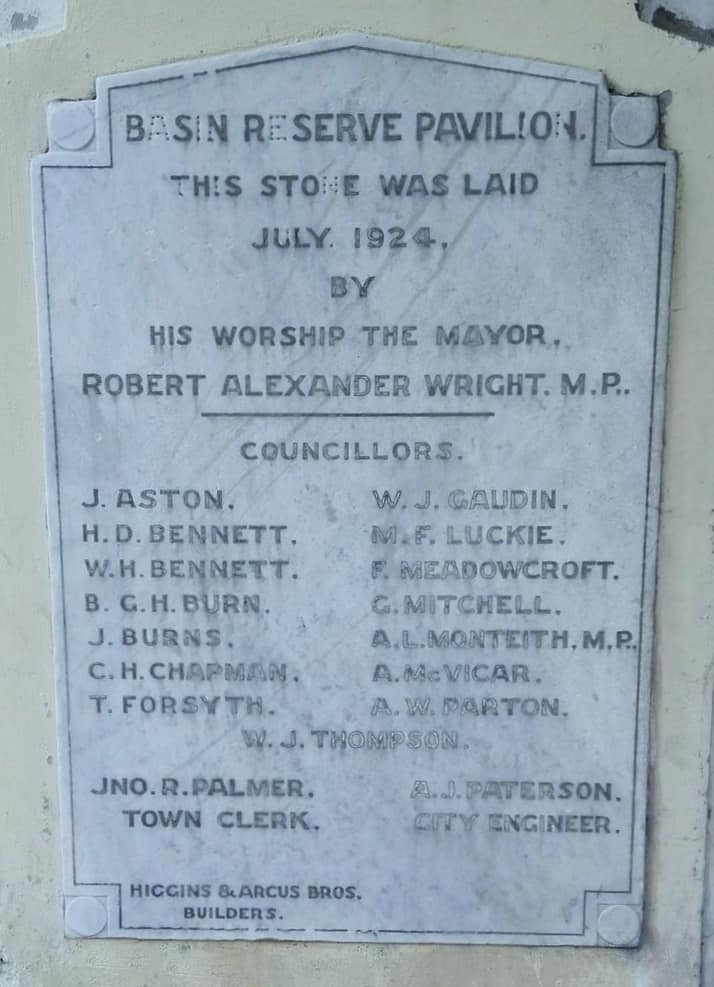

Needing to return to work George took a position as the manager of the Wellington cartage contractoring firm of Munt, Cottrell and Co. in 1923. His drive to stay fulfilled after the frenetic pace of war and three years in Parliament also compelled George to immerse himself in civic affairs. In 1924 he became Manager of the Wellington Show Association, a position he held until his death. He served as a Wellington City Councillor from 1923 – 1925, 1927 – 1931, a Wellington Harbour Board member from 1921-1929 of which he was Chairman, 1923 – 1925. For several years he was Chairman of the Board of Governors of Wellington Colleges, President of the Wellington SPCA, and a member of the Dominion Executive of the Federation of the S.P.C.A. from 1932, a member and sometime Chairman of the Wellington Free Ambulance Board, and a member of the Dominion Council of the Five Million Club (a sustainable population advocacy ‘think tank’ organisation) were some of George Mitchell’s more high profile commitments. He also omitted to numerous war relief and ex-service organisations.