8/293 ~ FREDERICK SMITH

This particular case struck a chord with me almost as soon as I had started the research. As I delved into Fred Smith’s life I discovered several coincidences which indirectly linked me personally to the Smith family. These I will relate at the end of this story.

Emma M. of Amberley in North Canterbury and husband Dion had just completed a trip to Dunedin and wider Otago in search of the last resting places of long lost relatives and ancestors, Dion having a particular interest in those ancestors who had served in both the First and Second World Wars. As a result of their genealogical interest, Emma and Dion have become the custodians of several family members histories including military precious memorabilia. After their return from Dunedin, armed with photographs of graves and yards of acquired information, Emma (the driving force behind the project) and Dion started to assemble the gathered information. One of the graves they had discovered in the historic Northern Cemetery in Dunedin, was overgrown and concealed a rather impressive polished granite grave marker. On the dressed side of the gravestone besides George and Annie Smith’s names, was their son Frederick, a WW1 soldier whose name commemorated his connection to the family. Frederick was buried on the other side of the world at Gallipoli. As Emma and Dion continued their search, they found the grave of another of George and Annie’s sons, George (Jnr.). Freddie Smith’s brother George had been cremated and his ashes buried miles away and, he was not memorialised on his parent’s gravestone along with Freddie – why was that so? The reason would become apparent as the research for this story progressed.

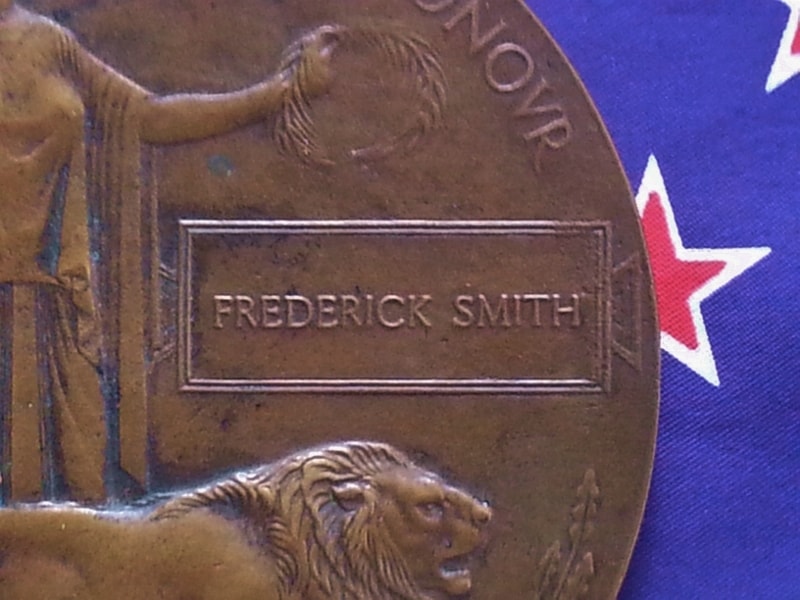

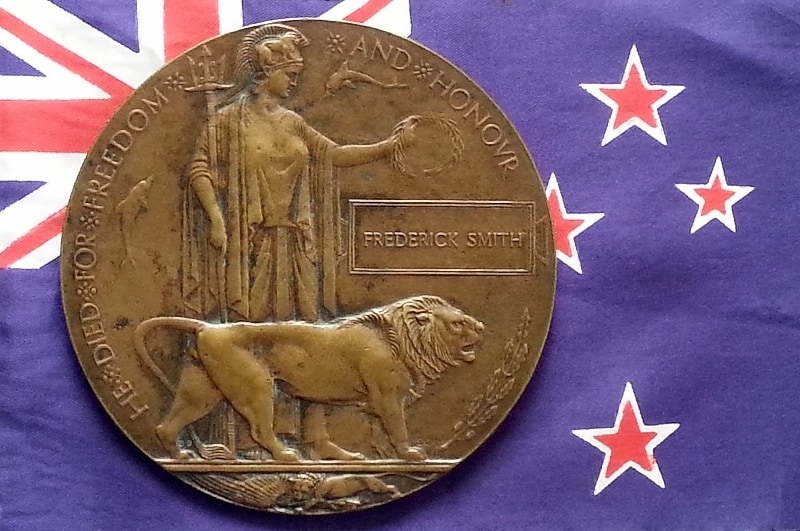

When Dion and Emma returned to Amberley a discussion regarding whereabouts of Fred and George’s war medals prompted Emma to check the Medals Reunited New Zealand website for help. Thanks to Haydn Jones of ‘Good Sorts’ and the item he did on MRNZ that aired on TV1 in May last year, both Emma and Dion became aware of MRNZ’s raison d’etre. Upon checking our website pages Emma had spotted the name of a soldier from Dunedin on the Medals~FOUND page. The soldier was Frederick Smith from Dunedin who had been killed at Gallipoli – and was also an ancestor of Dion’s. Emma contacted me about claiming Frederick Smith’s Memorial Plaque, and had also wanted to list both Frederick and his brother George’s medals as missing on our Medals~LOST website page since no living family member they knew had ever seen or heard of the whereabouts of either men’s medals.

The Memorial Plaque was received by MRNZ ‘in-confidence’ from a donor who wishes to remain anonymous.

The Smith Family

Anne “Annie” McCROSSAN (1864-1931) was a 19 year old Irish spinster from Derry, Cavan in Northern Ireland who had emigrated from Glasgow via London to New Zealand on the ship SS Caroline which arrived at Port Chalmers in May 1883. Annie McCrossan was one of 244 immigrant passengers, 133 of whom were single women, who were initially accommodated in the immigration barracks at Caversham in South Dunedin.

Londoner George SMITH, a stevedore and wharfinger, was 25 when he worked his passage from London to New Zealand in 1874. A wharfinger takes custody of and is responsible for goods delivered to the wharf, typically has an office on the wharf, and is responsible for day-to-day activities including slipways, keeping tide tables and resolving disputes. The term is obsolescent; today a wharfinger is usually now referred to as “Harbour Master”.

Forty year old George had been widowed in February 1888 from Scottish divorcee, Jane Smith (b: 1839 Colmonell, Ayrshire). A year later in May 1889, George re-married Dunedin resident Anne “Annie” McCrossan at the residence of the Mornington Presbyterian Church minister – a somewhat unusual match for a Catholic girl from Derry? After renting a number of short term temporary accommodation places in the city, the Smiths at last established a home in a small worker’s cottage at 26 Athol Street, a small cul-de-sac street in the centre of Dunedin not more than 100 meters from the central Railway Station. Athol Street ran from St. Andrews Street northward but stopped short of Frederick Street and comprised some 100 odd worker’s cottage dwellings. Athol Street no longer exists in the city having been merged with the Anzac Avenue however, confusingly there is another Athol Street at Ravensborne, NE of the city on the road to Port Chalmers.

Within the space of 10 years the Smith family brood at No. 26 had grown to a total of 11 children – there was Sarah, Joseph, James, Thomas, Martha “Eliza” Elizabeth, Joseph, George, Frederick, Margaret Annie, Thomas Hunter and last was Mary Catherine, known as “Kate” Smith. Not all had survived beyond infancy.

Frederick, (known as ‘Freddie’ or ‘Fred’) and his elder brother George (by eight months) were the only Smith family males to serve in the First World War. George, formerly a blacksmith, worked as a labourer/deck hand on coastal and trans-Tasman ships that regularly called at Port Chalmers. This gave George regular opportunities to visit with his family who had since moved around the corner to daughter Kate’s house in Harrow Street. It was December 1913 and most of the Smith family had returned home to No. 26 Harrow Street for Christmas. Much of the talk was of a possible war in Europe. There was also much interest and excitement as the NZ Military Forces started to prepare by calling for single men to volunteer for infantry, artillery or the engineers – the aim being to place them where their trade skills would be the most use. Able bodied and single men between the ages of 20 and 40 who were willing to sign-up for an ‘adventure of a lifetime’ were encouraged to apply. Both George and Freddie were caught up in the patriotic hype that swept through the city and the rest of New Zealand. Both were as keen as mustard to join the wave of young Dunedinites who enthusiastically queued at the Recruiting office door in Kensington Barracks in answer to their country’s ‘Call to Arms’.

Enlistment

Tapanui is a small rural Otago town about 150 kilometres due west off Dunedin. Prior to his enlistment, young Freddie Smith had been boarding at The Farmers Club Hotel where he had been employed as a labourer for hotel-keepers Patrick and Eliza McCann.

Pat McCann had been the head groom at the stables of a well known property owner in Lawrence. In 1881 Pat had married Freddie’s aunt, Eliza McCrossan and sister of Freddie’s mother, Anne McCrossan Smith. The McCann’s had moved to Roxburgh for better weather conditions and warmth shortly after their marriage due to Eliza’s ill-health. By 1893 Eliza was much improved and Pat McCann had decided they would move to Tapanui and purchase the The Farmers Club Hotel (before the days of “No-licence”) which was on the market but was not permitted to sell liquor. The McCanns proved to be genial and popular proprietors at what was known as a ‘temperance hotel’. These establishments provided all the usual services and facilities expected of a boarding hotel, except alcohol. Otago, like a number of other areas in New Zealand was in the grip of the anti-alcohol lobbyists which had resulted from years of its widespread abuse that started with the gold rushes. “No-licence” referred to the No-licence Leagues that proliferated around NZ, mainly run by ministers of the church and congregation members, who fervently promoted the ills of alcohol and advocated for national prohibition, often confronting or reporting sly-groggers (selling liquor without a licence). That concerned Pat McCann little, and he remained disposed towards selling grog ‘on the side’. As a result he found himself before the Judge on more than one occasion for sly-grogging. For licensed hotel-keepers fines for selling after hours or to minors in those days were imposed in terms of the confiscation of a number of litres of ale for the first two or three offences; thereafter the fines were in cash. Pat being the unlicensed keeper of a temperance hotel was fined in cash for each offence. His last offence (his forth) had cost him the equivalent of about $600.

Pat McCann also came to public attention in September 1901 when, after he and his wife had been engaged in a two month non-speaking feud, Pat had flown into a rage in the middle of the night over blankets his wife had taken from his room to hers. The net result was that Pat was remanded for trial on a charge of assaulting his wife with intent injure after he allegedly had stabbed her three times. Her wounds had resulted after McCann had broken down her bedroom door at 11.30 pm, knocked her sister to the floor (who slept with Eliza) and fought with both women on the floor in the dark which had resulted in several wounds and much blood, McCann allegedly having a knife in his possession. Boarders, guests and a policeman in the house had separated the group whereupon McCann disappeared for a number of days. When it came to the court case McCann was remanded to defend a charge of attempted murder. Fortunately for him he was defended in the Dunedin Supreme Court by the eminent and famous criminal lawyer, Charles Alfred Hanlon. The jury ultimately returned a verdict of “not guilty” finding Mrs McCann’s had actually be sliced not with a knife (that McCann was carrying but did not use) by broken crockery shards that had littered the floor as a result of the assault in the dark. Young Freddie Smith had been spared this embarrassment having started at the hotel in 1908. He continued to work at the hotel until he enlisted.

Note: Unfortunately Pat McCann apparently had been suffering from a terminal and painful ailment. The Southland Times of 15 May, 1916 reported he had committed suicide the previous afternoon, with a shotgun he had obtained from a hotel guest’s room. Pat’s wife Eliza soldiered on as the sole proprietor of the hotel for a number of years – she died in Tapanui in September 1946. Freddie Smith would never know Pat McCann’s fate.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

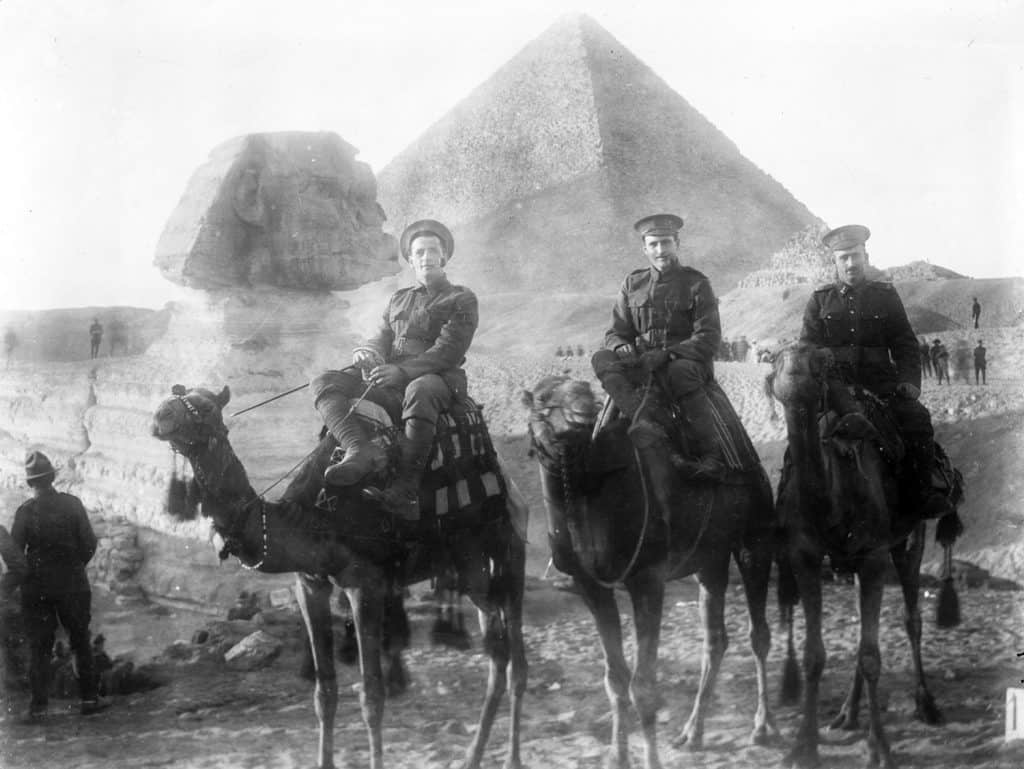

8/293 Private Frederick Smith was attested for service with the NZEF at Milton on 18 Aug 1914. He was described as 21 years old, 5’ 4” in height, weighed 9 stone 12 pounds (62.5 kg) with a dark complexion, grey eyes and black hair. Pte. Smith had trained at Trentham and returned to Dunedin before he embarked the HMNZT 9 Hawkes Bay at Port Chalmers on 16 Oct 1914 with the 14th Company, 1st Otago Battalion, one of the lead units that comprised the Main Body of the NZEF. HMNZT 9 sailed from Port Chalmers to Suez, Egypt and then on to Alexandria where the Otago Battalion troops disembarked on 03 Dec 1914 after 49 days at sea.

During his time on-board the transport Pte. Smith seemed to have issues with time management …. he was charged for being late for Tattoo roll call and given four days C.B. (Confinement to Barracks) in Oct 1914. He was then late (2 hrs) returning to HMNZT 9 at Alexandria and forfeited a day’s pay; at the NZ Base Depot camp at Zeitoun, 9 miles NE of Cairo, Fred was again absent from Tattoo roll call on Christmas Eve 1914 and remained absent until 0530. For this he was awarded two days CB and forfeited a day’s pay. To cap that off, prior to his departure for the Dardanelles, Fred was charged with having a dirty rifle and awarded another five days CB. Fred was obviously having trouble adjusting to this land of excesses that had welcomed “Massey’s Tourists” with eagerly opened tentacles.

Gallipoli – Sunday 25th April, 1915

There are no specific records of Fred’s service on Gallipoli which is not uncommon. The lack of records for troops serving on Gallipoli was quite normal after the landing and reflected the secrecy under which the attack had been planned. The dawn attack was to be a surprise landing (it wasn’t) and so little was written down until some months after the landings. From an administrative point of view record keeping at Gallipoli was complete chaos, a situation that continued for the first 18 months of NZEF service before and consistent and workable system had been devised. Hence the often muddled or incomplete service records of soldiers that we are left with today. Unit war diaries contained some general detail but rarely the activities of individuals – even casualties were reduced to little more than statistics due to the overwhelming numbers during the early days of the war.

A Gallipoli Day One survivor was 8/488 Private George Skerrett (Bluff) of the Otago Battalion described their landing at Anzac Cove on April 25th…..

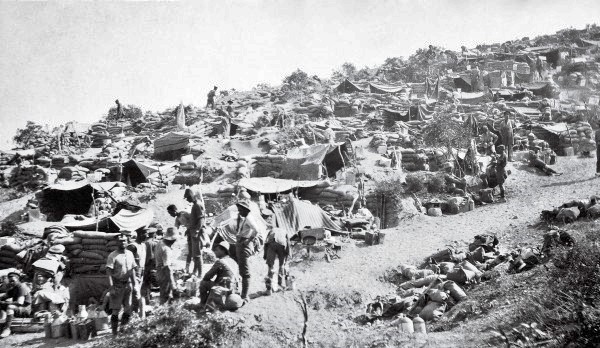

“We didn’t land until three in the afternoon. Ashore it was frightful terrible … We started to climb up Walkers Ridge, following the infantry up. Men were falling everywhere. We were right behind them, picking them up and dressing them the best way we could. I was part of the advanced dressing station. Stretcher bearers were getting them [the wounded] down to the beach as quickly as they could. That was going on all night.”

Pte. Skerrett also describes taking fire while at Anzac Cove:

“There was shrapnel coming down all the time. Day and night. The shells detonated in the air and the shrapnel came down like rain. I was walking along and I heard this bang, and a bullet landed near me. It was a sniper. So I lay down for a while and then got up and started to walk, when all of a sudden ‘bang!’ – another bullet just missed. So I lay down and pretended to be dead.”

Note: Pte. George Skerrett was lucky enough to return to New Zealand and lived to celebrate his 100th birthday in Christchurch. He passed away on the 30th June 1993.

Source: Te Karaka by Kurt Mclauchlan – Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

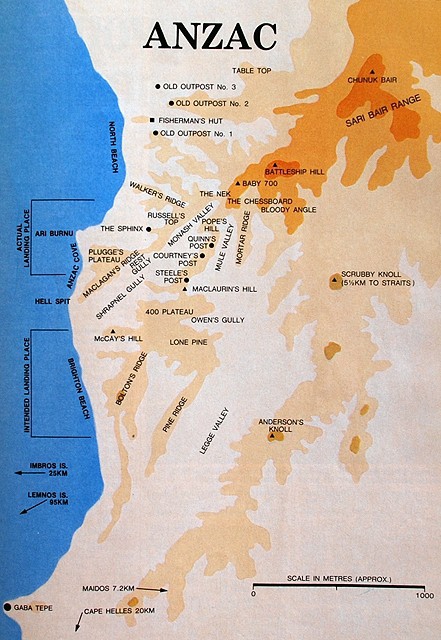

Pte. Fred Smith would not be as lucky. Seven days after the landings the Otago and Canterbury Battalions were attempting to straighten the NZ front line on the night of 2–3 May, which failed. Pte. Smith was wounded on the night of 2 May 1915 in a senseless night attack on Dead Man’s Ridge (Pope’s Hill). The attack was an attempt to overrun the feature Baby 700 which was heavily defended by the enemy. Pte. Smith was wounded in the head and chest by exploding bombs (grenades) hurled from the elevated positions of the Ottoman trenches. Fred lay on the field of battle for several hours in the darkness until he could be evacuated by the 1st NZ Field Ambulance (two men with a stretcher) to the nearest Advanced Dressing Station (ADS) in one of the semi-protected gullies on the southern side of Walker’s Ridge. Dead Man’s Ridge was one of the costliest actions involving New Zealanders on Gallipoli, with over 150 dead – nearly all of them from the Otago Battalion.

Advanced Dressing Stations (ADS) were located in the deep gullies of the Peninsula, the steepness of the terrain providing adequate protection from direct enemy fire and to a much lesser extent, protection from indirect artillery fire. The Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) was where the wounded from both field ambulances and ADSs were prepared for evacuation by barge to hospital ships and ambulance transports (nicknamed “black ships”) waiting offshore. But poor planning and the sheer unexpected volume of casualties at Gallipoli quickly overwhelmed the available medical resources (an estimated 1500 casualties by midnight of the 25th). During the April landings and the August offensive the ADS in the gullies and the CCS on the beach could not cope with the large numbers of wounded. These were mostly located in open air positions on the beach, either in the shadow of protective terrain or in semi-protected (sand bagged) positions on the beach, but all vulnerable none the less and which became targets of the enemy’s plunging artillery fire.

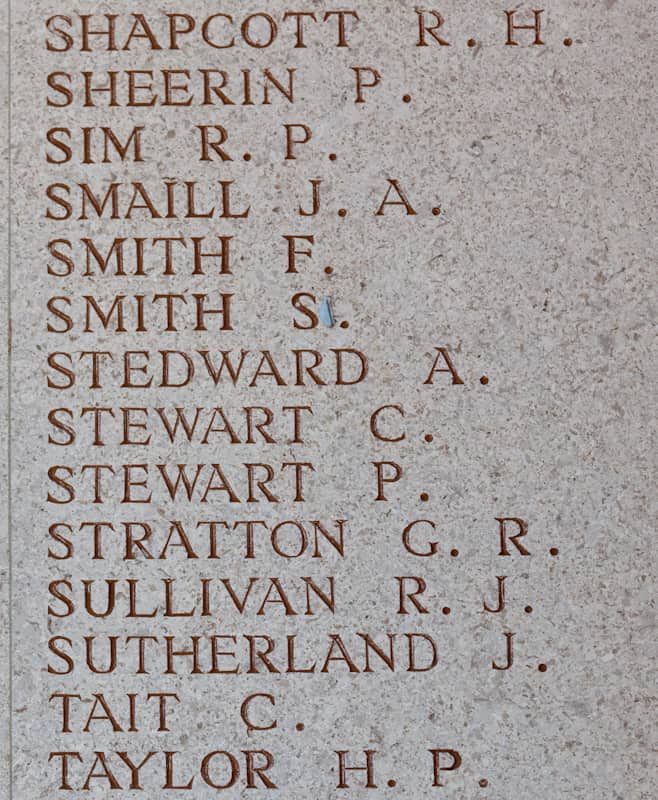

The extent of Pte. Smith’s injuries, together with the delay in his treatment and the chaotic management of mass casualties (at night), collectively conspired against his chances of survival. Death came quickly to Fred Smith as he lay in the Advanced Dressing Station – he died within a few hours on the 5th of May, 1915. Pte. Frederick Smith was buried on the Gallipoli Peninsula and is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial at Lone Pine Cemetery on Gallipoli. Fred was 21 years and 10 months of age.

Awards: 1914/15 Star, British War Medal 1914/18 and Victory Medal; Memorial Plaque; Anzac (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallion (1967)

Service Overseas: 1 year 143 days

Total NZEF Service: 1 year 202 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The eight month campaign in Gallipoli was fought by Commonwealth and French forces in an attempt to force Turkey out of the war, to relieve the deadlock of the Western Front in France and Belgium, and to open a supply route to Russia through the Dardanelles and the Black Sea. The Allies landed on the peninsula on 25-26 April 1915; the 29th Division at Cape Helles in the south and the Australian and New Zealand Corps north of Gaba Tepe on the west coast, an area soon known as Anzac. On 6 August, further landings were made at Suvla, just north of Anzac, and the climax of the campaign came in early August when simultaneous assaults were launched on all three fronts. Lone Pine was a strategically important plateau in the southern part of Anzac which was briefly in the hands of Australian forces following the landings on 25 April. It became a Turkish strong point from May to July, when it was known by them as Kanli Sirt (Bloody Ridge). The Australians pushed mines towards the plateau from the end of May to the beginning of August and on the afternoon of 6 August, after mine explosions and bombardment from land and sea, the position was stormed by the 1st Australian Brigade. By 10 August, the Turkish counter-attacks had failed and the position was consolidated. It was held by the 1st Australian Division until 12 September, and then by the 2nd, until the evacuation of the peninsula in December. The LONE PINE MEMORIAL stands on the site of the fiercest fighting at Lone Pine and overlooks the whole front line of May 1915. It commemorates more than 4,900 Australian and New Zealand servicemen who died in the Anzac area – the New Zealanders prior to the fighting in August 1915 – whose graves are not known. Others named on the memorial died at sea and were buried in Gallipoli waters. The memorial stands in LONE PINE CEMETERY. The original small battle cemetery was enlarged after the Armistice when scattered graves were brought in from the neighbourhood, and from Brown’s Dip North and South Cemeteries, which were behind the Australian trenches of April-August 1915. There are now 1,167 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated in this cemetery – 504 of these burials are unidentified. Special memorials commemorate 183 soldiers (all but one of them Australian, most of whom died in August), who were known or believed to have been buried in Lone Pine Cemetery, or in the cemeteries at Brown’s Dip.

Source: NZ War Graves Project

Note: While the story of Frederick Smith’s service and death at Gallipoli is tragic, it is also necessarily brief given the short period of time he actually served in the NZEF and the absence of any detail in his personal record. It is worthy of noting that Fred and his brother, 12/870 Pte. George Smith, had both faced the same Ottoman maelstrom of lead and shrapnel that greeted each successive landing of troops throughout that first day at Gallipoli. George’s unit, the 1st Auckland Battalion, was the leading New Zealand ANZAC unit to hit the beach at Anzac Cove along with the Australians, at dawn on Sunday, April 25th. The 1st Wellington Battalion followed the Auckland Battalion while Fred’s Otago Battalion had a short respite. They were not to be landed on the Anzac Cove beach until about 1500 in the afternoon and so with a good deal of trepidation, were able to preview the carnage they would have to face with when their turn to go ashore came.

George’s first seven days on the Gallipoli Peninsula were spent huddled in a nook carved into the hillside above Anzac Cove with his bayonet. To a large extent George’s first week paralleled brother Fred’s, but with one exception – George would leave the Peninsula alive. His story is intriguing in itself. Both brothers landing at Gallipoli on Day 1 of the campaign inextricably linked them in history. Against the odds both had survived until tragedy befell Fred, and he was killed. George’s story from that point also warrants being told. Not only did George have to contend with his brother being killed, but his own survival also became a tragedy, one that was played out during a long, slow death which would last more than 45 years.

George Smith (Jnr.)

12/870 Private George SMITH was a blacksmith by trade and former member of ‘B’ Company, 4th Otago Regiment. George had been working with his father George Snr. and older brother Joseph on the city wharves processing cargo from the smaller coastal vessels that shipped goods to Dunedin, when he decided to go to sea. He had no difficulty in being taken on, crew labourers were always in demand and he soon got a position on the cargo and passenger vessel, SS Maheno. The Maheno entered service in 1905 and was doing the Australia-New Zealand run when war broke out in 1914. In 1915 the NZ government requisitioned her to become a troop transport and hospital ship for the NZEF and required to undergo a re-fit before it was ready for service. Once completed the SS Maheno was re-titled HMNZHS Maheno for the duration of the war.

When George and Fred heard that New Zealand would be answering the ‘Mother Country’s call for troops from all Commonwealth nations to assist repelling the Bosch in Europe, both made their availability known by volunteering for NZEF service, Fred at Tapanui and George at Hamilton who was en-route with the Maheno to Auckland where he would be “payed off” on completion of the voyage. It was August 1914. George was immediately assigned to join the 1st Auckland Battalion whose regular service soldiers were already being prepared for active service. Since time was of the essence George was required to report to Trentham within days to start his training and preparation for overseas service. The Battalion was to form the vanguard of the Main Body of the NZEF which was scheduled to depart for England and the Western Front in October 1914.

Six weeks at Trentham taught George the essentials of infantry soldiering (barely) before he and the remainder of the battalion embarked HMNZT 8 Star of India at Wellington on 16 October 1914. Coincidentally, George’s brother Fred would be sailing on HMNZT 8’s sister ship, HMNZT 9 Star of India which was departing from Port Chalmers – both ships departed on the same day. Unbeknown to Fred, he would be bidding his mother Annie, sisters Eliza, Maggie and Kate, and brothers Joe and Tommy who had come to see him off – farewell for the last time.

After arriving at Suez the 1stAIB entrained for Cairo and then marched to the Battalion’s billets at Zeitoun. Time management and a rambunctious blacksmith’s demeanour also meant George would spend some time ‘chasing the bugle’ (Confinement to Barracks, or CB) for either being AWOL or not responding to his NCOs when spoken to, while in Egypt.

On 12 April 1915 George and the 1st AIB left for the Dardanelles where he became a ‘1st Day Lander” – 25 April 1915. George survived the landing, leaving the cove on 02 Aug temporarily for the relative calm of the HMHS Galeka – he was suffering from general debility brought about by the very conditions of living on the Peninsula. Most soldiers went down with this affliction at some stage. On 10 August George was attached to the British XI Corps as a Sniper. After just five days on the job George was on the receiving end of a Turkish sniper’s gunshot that fractured his skull. Over the next 10 days George was first treated and stabilised before being evacuated by hospital ship to the King George’s Hospital in London. George was scarred above & below the left eye. He had also lost

12/870 Pte. George Smith had served 1 year and 152 days overseas in both Egypt and Gallipoli, a total of 1 year 280 days of NZEF service. For his service George was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal.

Torpedoed

During his last medical assessment it was noted pressure had been building on George’s brain. Traumatic Epilepsy (TE) or TBI (traumatic brain injury) is used to describe the condition George suffered from. TE/TBI is a convulsive epileptic state caused by severe physical trauma to the brain. It is characterised by repeated epileptic-like seizures (fits) the onset of which could be delayed for months. In George’s case an operation was advised to ease the pressure and to hopefully prevent any further fits. His speech was reported as being slow, vocabulary was limited, he suffered headaches and appeared to be consistently dazed or disorientated.

George had had only one fit since arriving home and on the strength of that, he refused the operation and left hosp. He spent the next 10 months at home with his mother and sister at 26 Harrow Street, Dunedin in a depressed fog apart from the times he spent away on his uncle’s farm in rural Otago. No work however was possible.

While staying at his uncle’s farm in early 1917, George did the unthinkable – he signed onto a ship for sea service. The SS Kinross was a cargo ship that transited between Australia, NZ and England. As the war was still being fought on the Western front and increasingly on the high seas by surface craft and submarines, the Kinross had been armed with deck guns and depth charges.

George (25) left Dunedin on the SS Kinross in March 1917 bound for Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. After loading a cargo of wheat at Fremantle (Perth) the Kinross sailed for Liverpool. On May 7th the Kinross had all but made safe haven in English coastal waters when at 0155 (5 minutes before two o’clock in the morning) the ship was torpedoed in the starboard bow by the German submarine UC. 48. The Kinross was finished off by gunfire from the submarine and sank 19km East of the Wolf Rock near Lands End, Cornwall. Three life boats managed to get away, one boat carrying the Master (Captain Trebilcock) was picked up by the SS Crohan and landed at St. Ives, the second boat by the SS Forfar was landed at Penzance, and the third boat by a patrol vessel, was also landed at Penzance. All crew (including George Smith) had survived.

Following this event George joined another cargo vessel (unk) and sometime before July 1919, was again rescued after his ship had again been torpedoed. No details are available other than those recorded in his medical report. Clearly this affected George substantially and the shipping company sent him back to Australia. A short time later George returned to Dunedin arriving home in September 1918. From that time on he did little apart from seek relief for his on-going headaches and general debility. George had been temporarily admitted for treatment to the Seacliff Asylum near Karitane on the Eastern Otago coast north of Dunedin. He was released after a month of physical rehabilitation and electro-convulsive treatment (ECT) but without any noticeable improvement in his condition.

In March 1919, George’s progress was again assessed by the military medical authorities, having noted on his records his absence from the country and return to sea, his travel to England and subsequent occasions the vessels he was on were torpedoed – all of which George seemed to have achieved under his own steam. Clearly there was some rational function at that time. However George’s health, both mental and physical, after these incidents declined quickly. He had had re-current fits which were increasing in their frequency and remained in a semi-depressed state, but still he refused any operation. He left the hospital and returned home to 26 Harrow Street, his mother and youngest sister Kate. Such was the low level of understanding and availability of medicinal relief for brain injuries at this time, there was little more any medical authority could offer George by way of assistance to recovery – there was no recovery.

Seacliff

In March 1919 George Smith’s recovery progress was again assessed by the Army medical authorities who noted on his file his absence from the country and going back to sea after the previous assessment and recommended operation, his travel to England and the subsequent events regarding the vessels he was on being torpedoed – all of which by some miracle George seemed to have achieve (and survived) under his own steam! However these events together with his Gallipoli service traumas had caused George’s health, both mental and physical, to decline rapidly. Clearly he was suffering from a post-traumatic condition akin to ‘shell shock’. He had started to have re-current fits whose frequency were increasing, and he remained in a semi-depressed state but still adamant he did not want an operation. He again returned to his home and occasional visit to his uncle’s farm. The understanding of brain injuries and how to treat them was still being understood and various regimes trialled but effectively there was little treatment of any sort the medical authorities could offer George in 19120. George lasted at home until mid 1920 at which point his state of mind and general debility meant he could no longer be managed or cared for by his mother and sister.

On 11 June 1920, George (28) was re-admitted to Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, this time as a full-time ‘inmate’ destined to remain there for the rest of his life. Mention Seacliff these days to anyone who knew of it and its reputation, you will be regaled with horrific tales of a Victorian institution, of locked rooms full of uncontrollable ‘mad’ people, isolation cells, the death of 37 female inmates during a fire in Dec 1942 who had been locked in their ward at night, of the freezing conditions in winter, of beatings and other physical abuse akin to that of a jail and the burning of bodies in the onsite furnace room. This was to be George Smith’s life and death.

George was 73 years of age when he finally passed away on the 8th of December, 1965 – he had spent over 45 years confined in Seacliff, taking his last breath 50 years after his brother Fred was killed at Gallipoli.

~ R.I.P ~

George Smith is buried at the Anderson’s Bay Cemetery, Dunedin in the Soldiers Section. Fred and George’s mother Annie Smith died in Dunedin on 26 July 1931, aged 66.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My research of this case was limited to information for this post which made a pleasant change. Rather than me searching for a descendant to reunite with the plaque, the descendant in this case found me by first having seen my post on Frederick Smith’s AWM Cenotaph page, and by locating the his name on our Medals~FOUND website page. As a consequence I was able to start this post from a family tree which Emma kindly provided.

As I went through Dion’s family tree and reviewed the dates and location, I noticed several coincidences that resonated with me and the story of my own great-grandfather from Dunedin.

- The first coincidence was the fact that my own great-grandfather, Jack (John Ormsby) Sullivan (see How It Began) had also been born and raised in at home in Dunedin in the very same Athol Street the Smith family had lived – Jack Sullivan, Joseph, Fred and George Smith would doubtlessly have known each other growing up since all were of similar age and Athol Street, being a cul-de-sac with closely located dwellings, lent itself to every occupant knowing one another, particularly the children as their playground was generally the street.

- The second coincidence was that Jack Sullivan’s parents John and Margaret Sullivan (my great-great grandparents) would also very likely have known George Smith Snr. and Annie since not only did the live in the same street but John Sullivan had also spent time as a stevedore (watersider) on the Dunedin wharves when George Smith had been the wharfinger.

- The third coincidence is the Sullivan family (parents and a daughter) are buried in the Northern Cemetery in Dunedin, a stones throw from George and Annie Smith’s grave. As both Frederick Smith and Jack Sullivan had been killed in action and buried where they lay, their names are both commemorated on their respective family’s graves.

- The forth coincidence, not directly related to my research, I found on Dion’s family tree noting a name therein that was very familiar to me. Fred and George’s sister, Mary Catherine “Kate” Smith (married name SIMMONS) was Dion’s great-grandmother. Kate’s son and his wife, Dion’s grandparents, had had two daughters – Adrienne (Dion’s mother) and Lorraine. The coincidence was that Lorraine was married to a personal friend and as it happened my Christchurch realtor who had facilitated a purchase for me of my grandfather’s former Christchurch home, in the late 1990s. Bob had also been instrumental in the sale of the same house after the Christchurch earthquakes had wrecked it! I wonder how many ‘degrees of separation’ this represents?

Dion is a keen collector of military memorabilia but nothing comes close he reckons to receiving his first piece of genuine WW1 military memorabilia that commemorates one of his direct ancestors, a Gallipoli first day landing veteran he never knew existed. Dion, Emma and young Felix (the next generation custodian of the Plaque) are now the proud owners of Frederick Smith’s Memorial Plaque, currently being framed for display. Dion will also be acquiring two sets of Replica medals so that both Frederick and George Smith can be honoured in style each Anzac Day and Remembrance Day – we all remain ever hopeful the original medals that were awarded for Fred and George’s WW1 service will be found and reunited with this descendant family.

The reunited medal tally is now 212.