60075 ~ ARTHUR JAMES CONYNGHAM

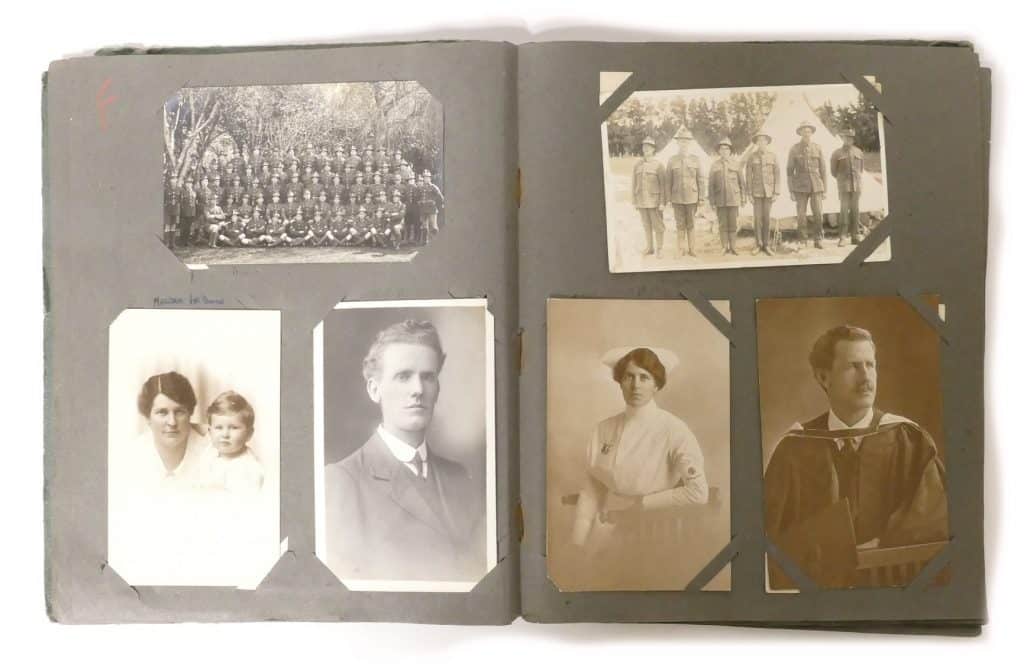

A recent scan of medal related websites turned up a pair of WW1 medals and some other items of ephemera of a New Zealand soldier that were about to be auctioned. Not an unusual occurrence so out of pure interest I looked up the soldier’s service file to learn something about him his service. In checking the file the first thing I saw was a message of remembrance dated 25 April 2017 that had been added by Sally T.

The author’s message was directed to a deceased great-uncle and the obviously caring sentiment that was expressed caused me to wonder why the soldier’s medals, a photograph album and his bayonet were being auctioned? Clearly Sally T. had no idea that this was the case, or maybe she did? Knowing full well that medals sold at public auctions can sometimes be the result of them being found by someone outside the family, sold as a result of theft, or even sold by a family member needing money, or one that is just not interested in keeping them, I decide to try an find out what the story was. I had nothing to lose and by contacting the author of the message I could at least alert them to their imminent loss of the medals. Given Sally’s message acknowledging her great-uncle, I felt sure she would want to know the medals of 60075 Private Arthur James CONYNGHAM were about to be auctioned?

I reasoned that in similar circumstances, had the medals been of my ancestors, I would very much appreciate someone alerting me to the fact they were about to be sold. So I sent a message to Sally T. outlining my reason for contacting her and of the imminent auction – a very prompt and favourable response came back. No, Sally was not aware the medals were being auctioned and yes, she was very interested.

Irish roots

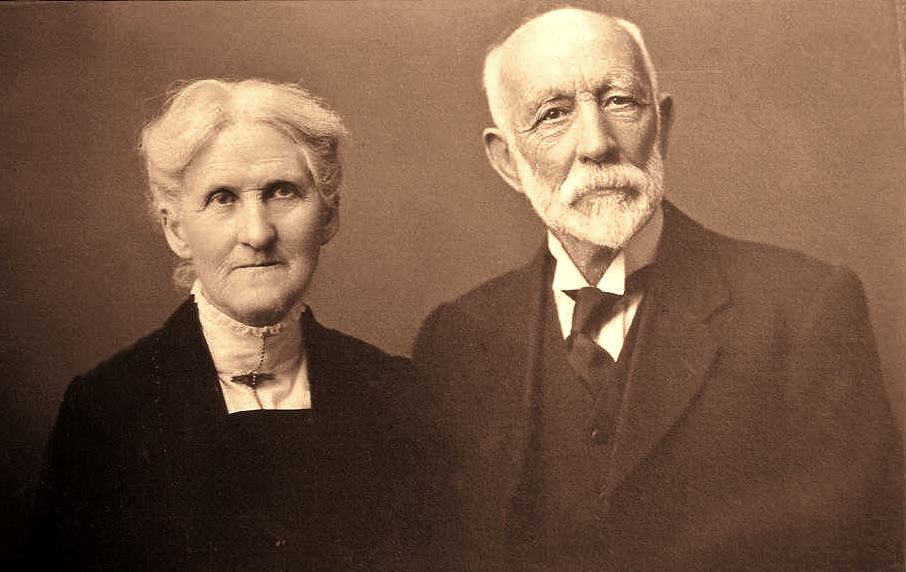

Irishman John Conyngham (1845-1937) born in Templemore, Londonderry, Ireland had arrived at Geelong in Victoria, Australia in June 1852. Barely seven years old, John arrived aboard the Mangerton with his parents Thomas Lecky CUNNINGHAM/CONYNGHAM and Jane CRAWFORD. Thomas, a Block Layer and later Mechanic, was soon seized by the ‘gold fever’ that was attracting prospectors from all over the world following the discovery of abundant gold at Ballarat. Thomas and his family headed to Ballarat however, Jane and their three children did not stay long. Within 12 months Jane and the children returned to Ireland the following year on the Great Britain. Thomas Conyngham eventually returned home to Ireland after a few years and there he stayed – he died in 1874.

Four years after his father’s death, John Conyngham (now 32 and an experience store keeper), his mother Jane and his two sisters, Elizabeth Frances (1849, Londonderry) and Rebecca Kerr (1852, at sea) immigrated to New Zealand on the Lady Jocylen and arrived at Auckland in August 1878, shortly thereafter establishing themselves in Whangarei where John Conyngham ran a general store.

While in Whangarei John Conyngham had met Annie Susan CLEARY (1864-1939), an Irish farmer’s daughter known as “Susan” who hailed from Philipstown (now Daingean) in Kings County (now Offaly County) of the Republic of Ireland (Eire, now Northern Ireland). John (36) and Susan (20) married in the Auckland Registry Office in Aug 1884. Over the following 16 years they grew their family to 11 children – Minnie Kerr RUSSELL (1885-1977), Frances Elizabeth BISHOP (1886-1967), Henry Macintosh (1888-1966), Annie Jane Glenny [Glennis] SUCKLING (1890-1974), Ruby Miriam BARRON (1891-1961), Arthur James (1893-1963), Rebecca Winifred ABERNETHY (1894-1983), John [Jack] (1896-1918), Charles Stewart (1898-1954), George Reginald [Reg] (1900-1980) and last Thomas (1902-1903) Conyngham.

Towards the end of his working life John bought land at Raumanga and invested in several mining ventures. Around 1890 he purchased 500 shares in the Young Colonial Gold & Silver Mining Company with 35 others. He also bought another 1000 shares in the Little Agnes Silver Mining Company with 44 other investors, and a further 1000 shares in the Jetta Gold and Silver Mining Company with 29 other investors. The mines were located at Puhipuhi, about 20 minutes NW of Whangarei. The outcome of his investments is not unknown by this author however proof of their viability and the area for precious metal mining could be judged from the success of New Zealand Quicksilver Mining Ltd. who had established a mine at Puhipuhi from 1907-1945, becoming one of three mines in the country to produce commercial quantities of mercury for use in the manufacture of instrumentation and munitions.

John Conyngham’s success might also be measured by the fact that he was frugal with his money, bound by a deep personal and conservative faith, and was sufficiently well off to ensure his sons were well educated. Henry became an accountant, Arthur a draper and company manager, John (jnr), ‘Jack’ attended Auckland Grammar and went on to study at the Auckland University College (now Auckland University) and worked for the Auckland Education Board, Charles (and Jack) passed the Civil Service entrance examinations with Charles becoming an insurance company manager, and Reg the youngest Conyngham son ran a drapers shop later becoming company director.

After the death of their infant son Thomas in 1903, John and Annie Conyngham moved their family into the growing city of Auckland. Their sons would need access to good schools if they were to be successful and so the family settled into 99 Crummer Road (later moving to 125 Crummer Road) in the suburb of Grey Lynn.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The road to war

In the lead up to World War 1 the government had called for the compulsory national registration in 1914 of all single males 20-35 years of age. Of the 10 surviving Conyngham children only two sons met (would meet) the age and status criteria for registration – at 21 years of age and single, Arthur Conyngham was eligible to serve immediately. Arthur’s 19 year old younger brother John (known as Jack), also single, would turn 20 in 1916.

Arthur was working as a shop assistant in a general merchant’s store specialising in the sales of materials and haberdashery which would eventually lead to a life-long involvement in the drapery and clothing industry.

Jack Conyngham was academically orientated and attended Auckland Grammar where he gained first prize in Mathematics and Science in his first year (Modern III as it was called) and again in his second year (Modern IV). He passed the Junior Civil Service exam in 1912 (Modern V) aged 15. Once he left school Jack’s first job was with the Union Steam Ship Company’s office in Auckland for about 16 months. In 1914 he left this position to join A & T Burt Ltd., a well known company started in Dunedin that provided marine and ship repairs and services, as well as plumbing and electrical installation services. At 18 years of age Jack attended the Auckland University College in 1914 and 1915 qualifying as a school teacher. At 19 he had not long joined the Auckland Education Board in 1916 and was teaching at Whangaroa North school, about 35 km NW of Kerikeri in Northland, when his 20th birthday signalled his call-up for overseas service. The eldest Conyngham brother, Henry Macintosh, 26 in 1914, although eligible by age to enlist had been recently married (1913) and therefore was exempted.

Conscription inevitable

Following the initial surge of patriotic fervour by volunteers which saw 8500 sign up for the Main Body of the NZEF, these were supplemented with two-monthly instalments of 3000 which were required to replace casualties and those removed due to sickness and hospitalisation. By 1916 the number of men volunteering had dwindled rapidly once the realities of the ‘great adventure’ became apparent. Casualty numbers, medically & mentally unfit for service, approved conscientious objectors, deserters had all come at huge cost per head of the eligible male population the longer the war continued. The recruiting age was pushed out to 40 by October 1915 and again to 45 by September 1916 but still the demand for reinforcements was suffering.

The answer was imposed by the government in October 1916 – conscription of all those eligible who had previously ‘avoided’ plus men of older age groups. Such was the shortage married men were volunteering and being accepted, and even men with pre-existing conditions previously rejected as medically unfit for service with earlier drafts, were being re-called and passed fit for overseas service.

Both Arthur and Jack Conyngham had both been Balloted to serve, Arthur’s enlistment falling in 1917 and Jack’s a year later in 1918 once he had turned 20. Arthur and Jack were no different from thousands of other single, young New Zealander men who had been balloted for war service. Those selected were either excited at the prospect of an overseas experience, pumped up with patriotism and just a hint of apprehension, and there were those who lived with a permanent anxiety and feeling of dread, a fear of the unexpected which tended to grow the longer the longer the war continued and the longer they waited to be called. The fear of going to war was also reinforced on a weekly basis by newspaper columns filled with the names of the dead, wounded, sick, missing or Prisoners of War, all of whom invariably known to men nervously waiting for their ‘call to arms’.

“You’re in the Army now …”

The answers to the last two questions on Arthur Conyngham’s E.F.2 were irregular, and telling:

- At the top of the page in the box marked “Religion” the Recruiting NCO wrote – Free Thinker

- Q 25. Are you willing to serve in the NZEF in or beyond the Dominion of NZ for the duration of the war and 6 months thereafter, if you service is so long required? – No

- Q 26. For which Reinforcement draft do you volunteer? – None; nor Home Service

The Oxford Dictionary interprets a ‘free thinker’ with the following synonyms: non-conformist, individualist, independent, maverick, dissenter etc.

Arthur Conyngham was clearly not happy at the prospect of going overseas, not happy at all, and had resolved to make his thoughts known in the hope his need for enlistment could be rescinded. His jitters at the prospect of fighting and perhaps dying in a foreign land at the hands of an unknown enemy was a perfectly natural feeling but unfortunately was not considered reason enough for he and thousands of other young New Zealand men to escape the conscription net. Jack on the other hand had resigned himself to serving overseas once he turned 20. He was somewhat less apprehensive than Arthur due to the training he had undergone as a Senior Cadet (school cadet military training) while at Auckland Grammar which was followed by his transfer to the 15th North Auckland Regiment when he left school.

The Conyngham Irish faith

The Conyngham household was presided over by devout Irish parents. The prospect of their sons going to war and killing others was an anathema to John and Annie Conyngham whose guidance had always been their staunch Irish faith (not RC) and set of beliefs which they had instilled into each of their children in growing up. Arthur, more so than his brother, was deeply affected by the prospect of going to war as it contravened the very core of his faith. Mandatory registration and part-time service in the army at home was one thing but conscription for overseas service was quite another.

Enlistment queries

Pte. Arthur Conyngham had signed his Attestation for General Service and been officially sworn to serve. In doing so he had sought to make it known to those in command of his devoutness and beliefs over which he was no doubt questioned, however it did him little good. Arthur had hung on to the vain hope he might be reprieved from enlisting if he politely explained his commitment to his Plymouth Brethren faith. The Army were unmoved by his respectful protestations but not entirely inconsiderate when it came to assigning him a job in the NZEF.

Whilst attempting to understand from Arthur’s file the origins of his objections, it was Jack Conyngham’s military file that provided me the answer. Up to that point I assumed I would be writing a story about a ‘conscientious objector’ but this was not to be the case. The clue I needed to understand Arthur’s stand was on Jack’s military History Sheet which told me why Arthur had answered Q25 and Q26 with the words he did.

Jack Conyngham’s file was just six pages long but unlike Arthur’s Attestation form, there were no irregular answers on his at all, save for the letters “P.B.” entered in the Religion box at the top of the page. I checked down the list of his answers to each question and specifically Q25 and Q26 … to which he had answered … “Yes” he was prepared to serve and complete his Reserve obligation after the war was over; and yes he had selected the next Reinforcement draft he was prepared to serve with – the “28th”.

“Free Thinker” on one Attestation form and “P.B.” on the other – what did this mean? The sixth and last page on Jack’s file was only a half a page of what was originally a two page document that was his enlistment Medical Report. The first page of the report was missing! As Jack went through his medical check the Doctor was required to enter the answer to a question which fortunately for me appeared on the part page that remained in the file – “Religious Profession?” The answer was – “Plymouth Brother”, something I knew nothing of nor in fact had ever heard of and consulted Mr Google for an answer, entering “Plymouth Brother”…

This brought up the following: ‘Plymouth Brethren’ described as a conservative, low church, non-conformist, evangelical Christian movement whose history can be traced to Dublin, Ireland in the late 1820s, originating from Anglicanism. Among other beliefs, the group emphasizes ‘sola scriptura’, the belief that the Bible is the supreme authority for church doctrine and practice over and above any other source of authority.

Arthur Conyngham had signed his Attestation for General Service and been officially sworn to serve. In doing so he had also sought to make it known to those in command, his devout beliefs which he was no doubt questioned about, however it did him little good. Arthur had hung on to the vain hope he might be reprieved from enlistment if he politely but firmly explained his commitment to his Plymouth Brethren faith. The Army were unmoved by his respectful protestations but not entirely inconsiderate when it came to assigning him a job in the NZEF.

There is little doubt Arthur’s enlistment into the NZEF in May 1917 stirred in him an overwhelming nervousness and sense of dread, as it did most others. The prospect of fighting and perhaps dying overseas was a perfectly natural reaction but one he could see no way of avoiding and slowly resigned himself to the fact he was going. A nervous and/or non-committed soldier in the front line can be as great a hazard to his fellow soldiers as the enemy and in sensing Arthur’s nervous disposition, the Army was not entirely unsympathetic toward him and provided a compromise – he would be assigned to a non-combatant role with the NZ Medical Corps (NZMC). Arthur would be a Medical Orderly which meant he would be gainfully employed whilst requiring him to take arms only for self-defence and for the protection of his patients.

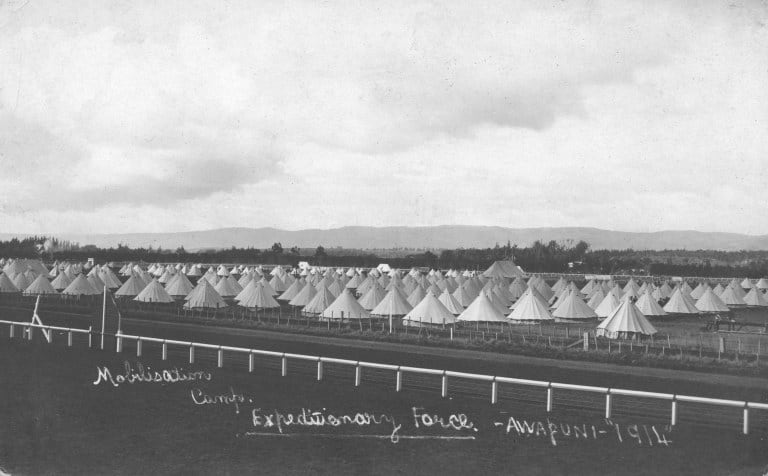

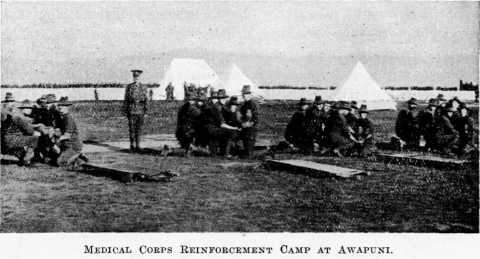

NZMC prepares for war… Awapuni

Whilst the camps at Trentham and Featherston were established to convert ‘citizens into fighting men’, the Manawatu Racing Club had lent the racecourse and facilities (which the Club also provided as their contribution to the war effort) to the NZ government for the purpose of establishing one of the largest training and mobilisation camps in New Zealand at the time. The Awapuni Mobilisation Camp at Palmerston North was established in 1914 to train and prepare the NZEF’s Main Body, and subsequently reinforcement drafts, before their departure to Egypt, Palestine, Salonika, France, Belgium and England.

Arthur had been assigned for service in Egypt with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), a somewhat less volatile front than the Western Front in France and Belgium. But none the less it was not without considerable danger. The Ottoman and German forces who had pressed their advance toward Cairo had not been entirely eliminated from the Egypt or Palestine and remained the focus of attention for the NZEF’s mounted units which saw them operating across the deserts of Egypt, Sinai, Gaza, and Palestine.

Pte. Conyngham joined the NZMC reinforcements who were due to depart New Zealand at the end of October 1917 as part of the NZEF’s 32nd Reinforcements. The NZ Medical Corps reinforcement recruits concentrated at Awapuni Racecourse, Palmerston North in July 1917. For the NZMC Awapuni was their primary training facility where medical orderlies and ambulance drivers were taught everything from squad and camp drill to clerical work, including how to inventory the possessions of the wounded, as well as the techniques of first-aid and managing battle casualties, casualty handling and stretcher bearing, Field Ambulance duties, Casualty Clearing Stations and Advanced Dressing Stations. Advanced instruction in the duties required of medical orderlies employed in Stationary and General Hospital duties was given at the Featherston Camp.

Having completed the basic medical skills training at Awapuni, Pte. Conyngham and his fellow NZMC recruits next headed to Featherston Camp on August 6th for seven weeks of hospital duties and ‘survival’ rifle training. The recruits reassembled at the Awapuni Mobilisation Camp on 25 Oct in preparation for their embarkation at Wellington.

Egypt – Suez & Moascar

Private Conyngham and the 32nd Reinforcements embarked HMNZT 98 Tofua at Wellington on 13 November 1917 together with 29, 30, 31, 33, and the 34th Field Ambulances plus the Mounted Rifles Reinforcements, for the five week voyage to Suez in Egypt. Tofua reached Suez on 21 Dec and the reinforcements were disembarked and transferred to the NZ Rifle Brigade facilities at Moascar Camp, located about 3 kms into the desert, west of the Suez Canal and town of El Moascar. The Camp was bounded to the south by the Sweetwater Canal (it wasn’t!) and the Suez Canal to the East, open desert to the north as far as the Mediterranean Sea and to the west as far as the eye could see – that was the direction from which the Ottoman’s approached. Moascar Camp was the assembly point for all Rifle Brigade and Medical Reinforcement personnel posted to the EEF. Operations were wide ranging and could include anywhere along the Mediterranean Coast, across the Sinai Desert to Gaza, south as far as Jordan and east into Palestine as far as Jerusalem.

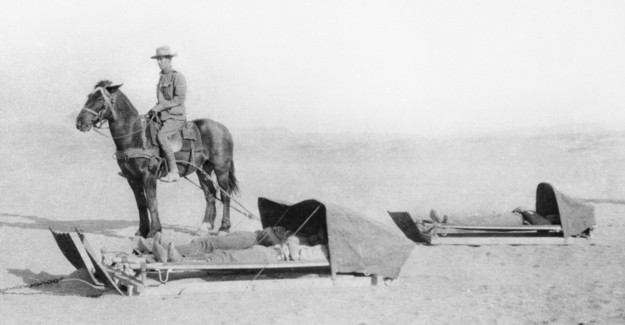

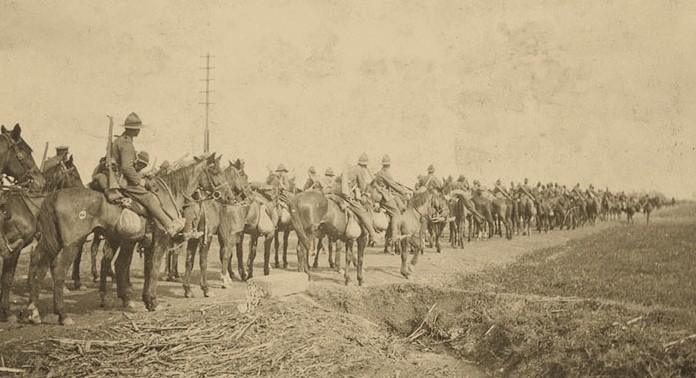

On his arrival at Moascar, Pte. Conyngham was transferred to the NZ Mounted Rifle Brigade and attached to the Mounted Field Ambulance working with 2nd Battalion, Wellington Infantry Regiment. Here he would learn techniques and gain valuable experience of operating as a mounted field ambulance orderly and the responsibilities of taking care of animals. The EEF had been heavily engaged repelling probing Ottoman force attacks virtually from the Suez Canal backwards towards Palestine across the Sinai desert. Stiff pockets of both Ottoman and German resistance were being encountered in places such as El Gorah (Sinai), Gaza, Beersheba as well as more distant points in greater Palestine (Israel) such as Bethlehem.

Added to this were the ever present swarms of malaria bearing mosquitoes and continual battle against unsanitary food and hygiene conditions that produced rampant outbreaks of dysentery from time to time among the EEF troops. Environmental hazards were also the enemy of the EEF – dehydration, sunburn and sun stroke, eye infections brought about by flies and other wind borne diseases, and desert blindness from reflection off the sand, all added to the conditions that plagued the men. The net result was a growing number of hospitalisations and long Sick Parade queues for as long as the NZEF remained in the Middle East. Pte. Conyngham’s rudimentary medical skills acquired in his preparatory training were in high demand, not only for the day to day camp medical aid duties, but they with the Training Regiment and for enemy operations in the Sinai and Palestine.

Posted to the Mounted Field Ambulance (MFA), Pte. Conyngham firstly underwent a number of weeks training in horsemanship before being attached to a Mounted Field Ambulance Troop for patrolling duties from Jan–May 1918 with a variety of the Brigade’s mounted units. From July 1918 onward his MFA Troop was attached to the Canterbury Mounted Rifles (CMR) to provide medical aid support for operations in the field. Later in the year Pte. Conyngham was transferred to work with the medical support provided to the Mounted Rifles Training Regiment at Ismailia, on the banks of the Suez Canal.

Rumours of an end to the war had been circulating for a number of months and as the end of the year approached, were confirmed with the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918. However, it would take quite some time after that date to get the message to all NZEF personnel and therefore for enemy operations to cease entirely. In the meantime there was still work to be done by the mounted riflemen and the NZMC.

Return to Gallipoli

On 27 Nov 1918, Pte. Conyngham’s MFA Troop and the CMR embarked HMT Huntscastle at Kantara and departed the next day for the Dardanelles. The CMR and 7th Australian Light Horse Regiment were required to return to the Gallipoli Peninsula for the purposes of monitoring Ottoman compliance with the terms of the Armistice. The global spread of the Influenza epidemic at this time was also about to affect the EEF.

After a day anchored at Lemnos the first signs of Influenza among the men of the CMR start to appear on the 1st of December. On 5 Dec HMT Huntscastle had anchored of Canackkale in the Dardanelle Straits where both Regiments started to disembark onto the Gallipoli Peninsula which would take three days. Once disembarkation had been completed on the 9th of December, 25 men were loaded and evacuated to the hospital on Lemnos with Influenza. By the end of the month 11 men would be dead from disease and 94 more evacuated to hospital.

Pte. Conyngham returned to Port Said, Alexandria from the Gallipoli Peninsula in late Feb 1919 and was due for a 14 day rest period before returning to the field at Ismailia and the CMR Training Regiment. While with the CMRs, Pte. Conyngham was promoted to Lance Corporal in June however relinquished the rank after just two weeks at his own request – not an uncommon occurrence for many men; some just did not want the responsibility that went with rank, while others proved to be unsuited to being an NCO or being thrust into a leadership role.

The first week of July 1919 heralded the start of a process Pte. Conyngham had longed for from the day he embarked at Wellington – Demobilization – which meant he was going home. Demobilization – the accounting and return of equipment clothing, payment of allowances due and the myriad of administrative task that required completion before leaving. Medical checks were a vital part of the ‘Demob’ process and were conducted at Ismailia. Not unsurprisingly the Senior Medical Officer noted on Arthur’s file: “Condition – marked nervousness.”

Homeward bound

23 July 1919 was ‘E Day’ – Embarkation Day. Pte. Conyngham said farewell to his MFA Troop colleagues and the CMR troopers he had worked with, and boarded HMT Ellenga at Suez to start the five week voyage back to New Zealand. Arthur’s tour of duty was over at last … he had survived surprisingly well physically (not even a bout of malaria) but mentally he was still very anxious – anything was possible on the return journey. Arthur had been a most unwilling soldier but to his credit had ‘bitten his tongue’ and got on with the job; he had done his duty as a Mounted Field Ambulance medical orderly and soldier, without question. The last of Arthur’s demobilization administration was completed at Trentham after which he was returned to his home and family in Auckland. Pte. Arthur Conyngham was officially discharged from the NZEF on 9 October, 1919.

Awards: British War Medal, 1914-18 and Victory Medal

Service Overseas: 1 year 303 days

Total NZEF Service: 2 years 104 days

Notes:

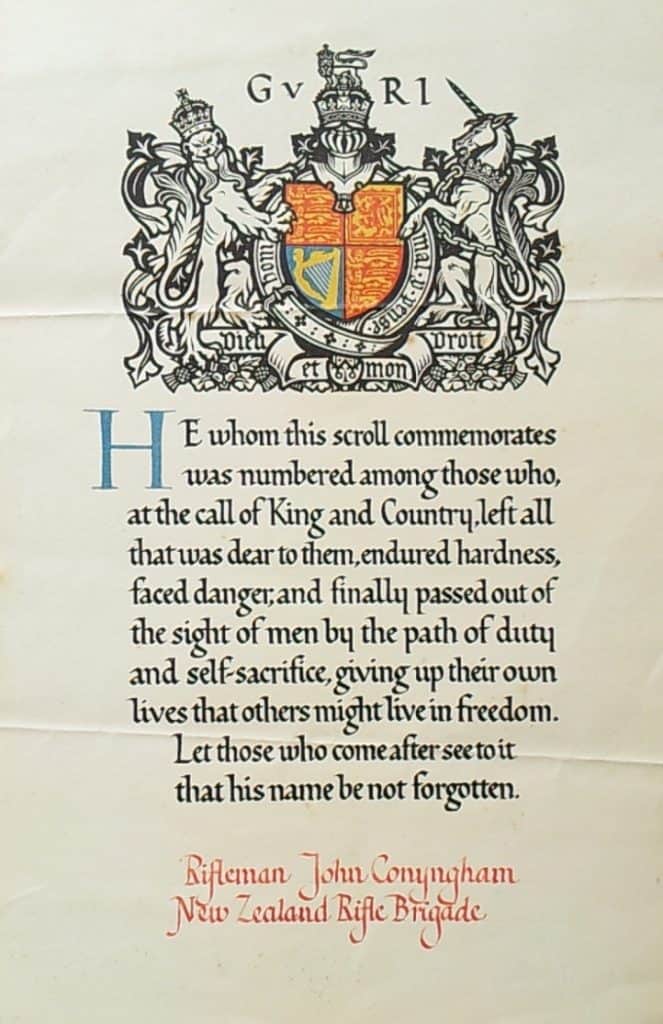

Arthur’s brother 53730 PTE-RFLM John (“Jack”) CONYNGHAM – NZRB 27th Reinf C Coy, 3Bn/3NZ Rifle Brigade was the sole teacher at Whangaroa School when he was attested for war service at Kaikohe on 29 March 1917. Pte. Conyngham proceeded to Featherston Camp for his basic training and on 12 June he embarked HMNZT 87 Tahiti and sailed for England. He trained at the NZ Infantry & Reinforcement Depot at Sling Camp on the Salisbury Plain. Pte. Conyngham embarked for France on 23 Sep and on arrival was posted to the 15th Company, 3 Battalion of the Auckland Infantry Regiment. In Dec 1917 he attended a School of Instruction in England and on his return to France in April 1918, was re-rolled as a Rifleman and posted to ‘C’ Company of 3 Battalion, 3rd NZ Rifle Brigade.

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final period of the First World War, during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the Central Powers on the Western Powers from 8 August to 11 November 1918 that began with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive essentially pushed the Germans out of France, forcing them to retreat beyond the Hindenburg Line, and was followed by the Armistice. It was during this offensive that Rflm. Conyngham was fatally wounded on the 9th September. Evacuated by the NZ Field Ambulance to No. 49 Casualty Clearing Station at Colincamps, about 40 kms NE of Amiens, Rifleman John Conyngham (22) succumbed to his wounds ten days later on 19 Sep 1918. He is buried at the Euston Road Cemetery at Colincamps, Somme, France. Jack Conyngham is also remembered on the Auckland Grammar War Memorial.

Conyngham men in WW2

During WW2 the son of Henry Mackintosh and Amy Conyngham, 639106 Sergeant John Bryan CONYNGHAM, NZ DIV HQ, 2NZEF (accountant) served at 2NZEF’s Base Camp in Maadi, Cairo from 1946-1948.

NZ411469 Flying Officer Russell Henry SUCKLING, RNZAF (painter) was the son of Nathaniel and Annie Jane Glenny (Conyngham) Suckling. An Avro Lancaster Pilot in Bomber Command’s 44 (RAF) Squadron, 26 year old Russell was killed over Germany on 28 Sep 1942 on his seventh operational mission. He is buried in the Reichswald Forest War Cemetery, Kleve in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany.

Post-war

After the war Arthur Conyngham continued in the drapery and clothing industry. He married Florence HEATH in 1921 and their one and only child, daughter Lynda Florence CONYNGHAM was born the same year. Arthur became the manager of an Auckland drapery business however the Depression years of the 1930s meant he was once more took on a sales job, this time in Huntly. At the onset of WW2 Arthur, Florence and Lynda moved to Hamilton where they settled comfortably into the drapery business until the mid 1960s whereupon the family returned to Grey Lynn. It was here Arthur and Florence retired and lived out their days.

Arthur James Conyngham died on 12 October 1983 at the age of 90, and Florence his wife on 13 August 1990 at age 98. Arthur’s ashes are buried in a family grave at Waikumete Cemetery together with his parents, Florence and members of the Conyngham family.

Going, Going ….. Gone !

Ten days after I contacted Sally with the news of Arthur Conyngham’s medals going to auction, I received the following:

Hello Ian

Just letting you know that I have been to the auction today and purchased those items. Paid far too much! But what do you do! ?? There were at least ..x.. other bidders. The album … all good as there is a photo of my father in there.

My husband is partial to swords and has a few so he will be pleased. [to have the bayonet]

We appreciated your email very much.

Regards … Sally

Further correspondence with Sally revealed that Arthur and Florence’s only daughter, Miss Lynda Conyngham, now 91, had recently downsized and in the process had disposed of unwanted items. As Miss Conyngham had no other immediate family members left to pass any personal items on to, she may have been of the belief no-one else would be interested in her father’s medals and so let them go to auction with the rest.

Sally, who realised the importance of the medals and the photograph album as items integral to the Conyngham family history in New Zealand (and in which she found a picture of her father!), was very grateful to MRNZ for the opportunity to recover her great uncle’s war medals and the other items – an opportunity that very nearly never was!

The reunited medal tally is now 216.

(including the Photograph Album and Bayonet)

Footnote:

A timely reminder – this is yet again a reminder to families who have had an ancestor who was awarded medals. If you value these know where they are and who has guardianship of them on behalf of the family – before it is too late! Once they are gone from family ownership you will very rarely ever get an opportunity to recover them.

Boer War and WW1 campaign medals are highly collectible and continue to increase in value with the passing of time – all are now over 100 years old. Because these medals – Queen’s South Africa Medal, 1914 (“Mons”) Star, 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal, were named before issue there is always the possibility medals, Memorial (“Death”) Plaques or Anzac (Gallipoli) Commemorative Medallions can be returned if found.

WW2 campaign stars (there are nine of these), general war service medals (three), and Memorial Crosses for those who were killed or died as a result of war service were all issued un-named (unless privately engraved). As a consequence they do not command the same prices as named medals, however more importantly if lost, they cannot be traced or returned. Generally speaking if you have lost an ancestor’s WW2 medals you should consider replacing them by either acquiring genuine original replacements from Trade-Me or eBay, or alternatively, purchase Replica replacements.

NB: The NZ Defence Force will not replace lost or stolen campaign or service medals, nor do they sell them.

Officially unveiled in 1929, the NZ Medical Corps War Memorial honours the contribution and sacrifice of the Officers and Soldiers of the New Zealand Medical Corps (NZMC) during the Great War. After refurbishment in 2016 it was re-named the Royal New Zealand Army Medical Corps (RNZAMC) Memorial to honour the memory of all military medical staff who have served overseas. It is the only known monument in New Zealand dedicated solely to commemorating military medical staff.