58422 ~ ALBERT EDWARD DENHAM

Following a house removal, Jan R. was clearing out some old boxes of accumulated “stuff” during which she happened across a pair of First World War medals she recalled her husband had found in the garage of a property they bought in Omokoroa more than 20 years previous. Not knowing quite what to do with the medals after an unsuccessful attempt to find the family of 58422 RFLM. A. E. DENHAM N.Z.E.F. to whom the medals were named. Jan says she decided to hold on to them hoping to further research a possible return in the future.

Jan’s initial research had shown that the house they had bought at 54 The Esplanade in Omokoroa at one time belonged to the family of George Albert DENHAM. The house had been sold by George Denham around 1994 after which it had passed into the ownership of others before being purchased in 2007 by the Jan and her husband.

Jan’s inquiries also conclude that George Denham had been living in the house with his wife and son until about 1990 after which anecdotal evidence suggested they had gone to Australia.

My findings were that Denham’s had indeed gone to Australia, twice, the second time they permanently. George Denham however had retained ownership of No 54 and rented it out for approximately four years before finally selling it in the mid-1990s.

The R’s purchased No 54 around 2005 and it was during their occupancy and renovation of the property that Jan’s husband discovered the medals apparently hidden in the garage. After unsuccessful attempts to find any Denham family connections to George, Jan put the medals aside for the time being and, as we all do with inconclusive projects, forgot about them until rediscovering the medals some years later during a house move to Thames-Coromandel.

“Good Sorts”

The subject of returning the medals was refreshed in Jan’s mind in mid 2017 after she had seen an episode of TV1 “Good Sorts” program in which host Haydon Jones featured the work of Medals Reunited New Zealand©. This prompted Jan to do something about finding an owner. The program was the catalyst for Jan to make contact with me to see if I could help with finding a Denham descendant. No problem at all, that is what we are here for ….. and so Jan sent us the medals so we could check them for authenticity, accuracy of the naming and assess the condition of the medals.

A personal connection

When I heard the medals had been found in Omokoroa, my attention was immediately focused as I too had lived in the rural beach side settlement in the early 1960s as a primary school student. Co-incidentally the Denham’s house at No 54 on the Esplanade intersected with the same street that I had lived in at No 15 Harbour View Rd, no more than 300 meters as the crow flies from No 54. Our family moved after twelve months in harbour View Rd to a farm house adjacent to the Omokoroa Point School. The farm is now a well developed suburb known as Unsworth Heights, being named after the family of the two property developers who had owned the farm, Alan and Neil Unsworth. I have many happy memories of Omokoroa in those early years, of fishing, boating and stealing apples from Mr Crapp’s vast fruit orchard that covered a good portion of the Point, while dodging his angry presence and potentially present shotgun, by hiding in the two metre deep, semi-collapsed trenches that were scattered throughout the orchard. These were the remnants of defensive fortifications that had been dug by local Maori as part of a complex early warning and defensive systems around Pukehinahina (Gate Pa), the site of a fierce if somewhat confusing battle in April 1864 between the British Regiments and Maori occupants of an extremely well designed and prepared fortification. The battled resulted in the British being soundly thrashed and General Cameron’s reputation severely tarnished. I digress …

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Denhams of Nowich

My research of the Denham family started with Albert Denham’s military service file. Born on May 1897 and educated in Norwich, England, Albert had emigrated to New Zealand with his parents and three sisters, arriving in Wellington in March 1914. It was in Wellington the Denhams made their home for the next Too young to enlist for war service when volunteers were called to join the initial reinforcement drafts, Albert had sought work in the city in the interim.

George Denham (1858-1942) was a 56 year old Carter from Norwich. George and his wife, Charlotte Edith FARROW (1865-1932), 48, left the relative comfort of their Norwich home with three of their six adult children and a nine month old baby, and embarked the SS Athenic in Feb 1914, the start a journey of emigration to New Zealand.

Eldest of the four Denham offspring was 17 year old Albert (farmer) known as ‘Bert’, then Margaret Jean, 15 (a Domestic Servant) and baby Emma Denham left London on 5 Feb 1914 and arrived in Wellington on March 26th. The Denhams other three adult children were already in NZ. Ellen Isabella DENHAM (b:1889) a spinster, and Louisa CLEAVER (1891-1961) had arrived in New Zealand on the SS Arawa one year before in Feb 1913, while son Herbert Denham (b:1892) being a merchant seaman had established himself in Wellington and was currently working on coastal and trans-Tasman cargo vessels by the time his parents and remainder of the family arrived. Perhaps it was Herbert and his older sisters who had sold their parents and siblings on the opportunities that abounded in pre-war New Zealand? The country’s economy was booming but industry and the trades were hampered being desperately short of manpower. The impending war in Europe must also have been a motivating factor for George Denham Snr to move his family to the comparative safety of the Antipodes.

The Denham family’s first temporary home was in Willis Street, rental accommodation in the central city until the George secured regular work as a labourer. He then moved his family to 19 Sidey Street in the city where they remained for a number of years, eventually moving to the coastal hillside suburb of Island Bay in Wellington’s eastern suburbs. Island Bay and the adjacent suburb of Miramar were favoured suburbs for many new immigrant families, particularly from the United Kingdom. They were both affordable and conveniently located, being close to the city centre and the port …. and for those on the upper slopes of the hillside, a brilliant view to the south over Cook’s Strait.

‘Colonial’ volunteer

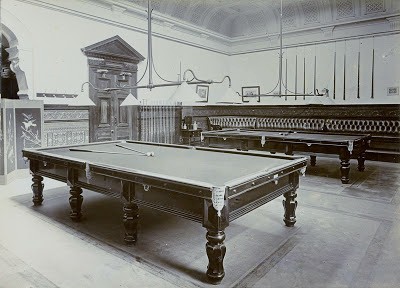

Note: Wellington Commercial Travellers and Warehousemen’s Club Company Ltd., was described in 1897 edition of the Cylopedia of New Zealand (Wellington Provincial District) as follows:

This flourishing Club has 180 members of the Association who enjoy club privileges, besides eighty purely club members. The whole of the profits are paid over to the Commercial Travellers and Warehousemen’s Association to provide for any contingency. Finding the premises much too small the directors decided to build. Their new club house is situated in Hunter Street, next Messrs. W. M. Bannatyne and Co.’s warehouse. The cost of the building and fitting is over £2400; it is an imposing structure of two stories, built in brick, and having every necessary comfort, the ceilings being of embossed zinc instead of plaster. On entering the handsome hall, a Strangers’ Room is found on the left hand side. A very large billiard-room is right opposite the entrance door. This room contains two fine slate bed tables by Allcock, and is said to be one of the finest in the Colony. A card-room and bar open from this apartment. A very handsome staircase leads to the first floor where the reading-room is situated, of large dimensions, handsomely furnished, having three windows, and containing an abundant supply of current literature. This room is a credit to the club. On this floor also there is a comfortable writing and card-room. There are lavatories on both floors. Altogether, the new club house in Hunter Street is creditable alike to the city and the Association.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

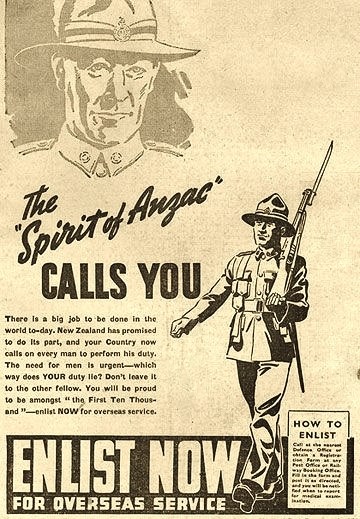

58422 Trooper Albert Edward Denham was 20 years and 4 months old when he was enlisted on 19 October 1917 and entered Featherston Camp with the 35th Reinforcement draft of the NZ Mounted Rifles. The war was at progressing at “full noise” as they would say, and the casualty count was climbing with hideous regularity. By mid 1917 men previously deemed unfit, too old or married, were being reconsidered for service as the volunteer streams had all but dried up and national conscription had been introduced. This perceived cure for soldier shortages at the front was introduced in October 1916, whereupon a dreaded monthly “ballot” of names of eligible men to serve, was drawn from a barrel and published publicly. Fortunately for Albert he did not attract the derision or stigma that many conscripts and evaders did.

Just 11 days after his arrival at Featherston, Tpr. Denham became Private Denham. The need for Infantry by far outweighing the need for mounted infantry and Albert was reallocated to the 3rd NZ Rifle Brigade and transferred to the 36th Reinforcement draft. By the time he embarked, another stroke of the pen re-titled Private Denham to Rifleman Denham, ‘C’ Company, 3rd Battalion, the NZ Rifle Brigade – surprisingly he remained with the 36th Reinforcements!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

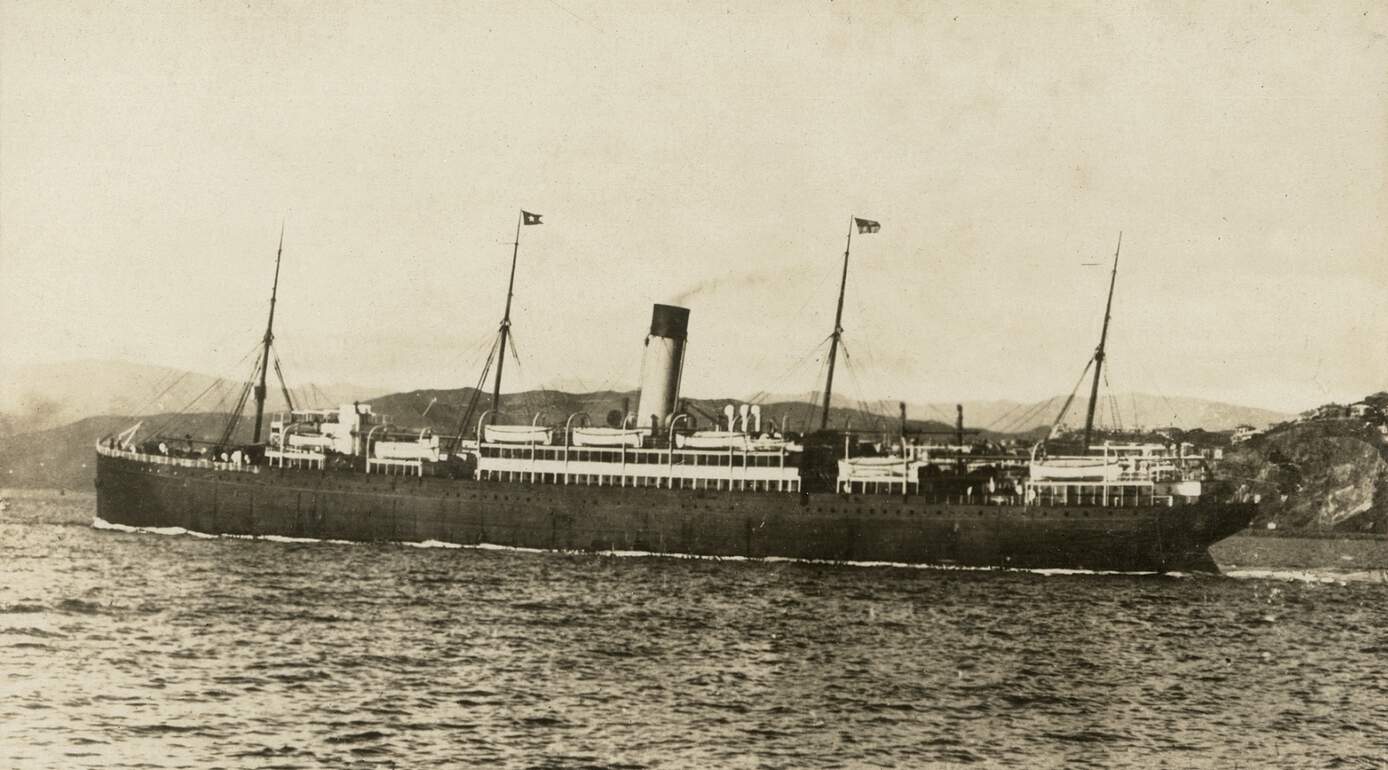

The training completed followed by some home leave, Rflm. Albert Denham embarked HMNZT 101 Tofua at Wellington on the 2nd of March 1918 and sailed for Southampton, England via the Suez Canal. It had been too dangerous to take the usual rout to England across the Pacific and through the Panama Canal, or even around the western coast of Africa. Submarine services while still in relative infancy of sophistication were managing to take a significant toll on unprotected troop, passenger and cargo vessels, as were marine mines. So the routes of least exposure to open seas and the threats of submarine attack such as the trans-Pacific route presented. Sea routes where a level of naval escort protection could be provided, were rigidly adhered to which took all allied shipping through the Suez Canal which was under the control of the Egyptian, New Zealand and Australian forces.

The 36th Reinforcements reached Suez on 22 March and required to disembark. For the next fourteen days the 36th were ‘guests’ of the Australian Camp at Suez.

Brocton, Cannock Chase

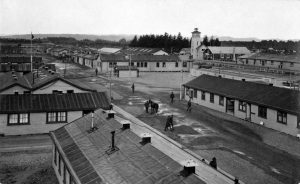

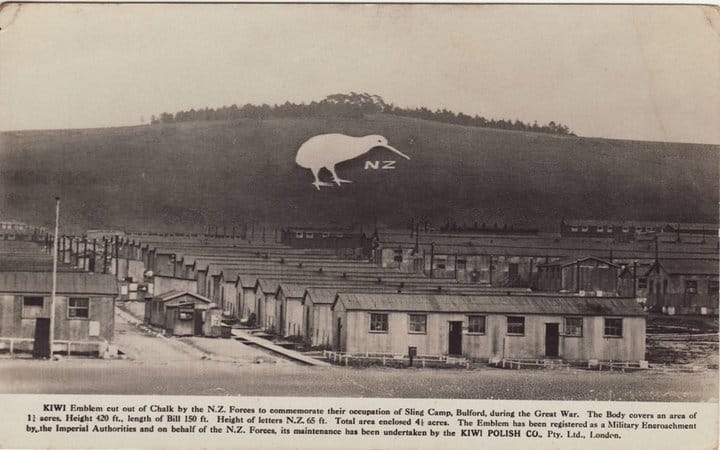

On 30 April, the troops re-embarked and headed for Southampton. On arrival the 36th were entrained and taken to a Brocton station, detrained and then marched the remaining 4 kms to Brocton Camp situated on the northern edge of Cannock Chase, Staffordshire. One of two NZ camps that had been established to accommodate and train NZEF Reinforcements, the other being the well known Sling Camp about 195 kms south of Brocton in the centre of the Salisbury Plain, Staffordshire. The new arrivals were marched in to the NZ Infantry & General Reserve Battalion (NZI & GRB) on 15 May and given over to the “tender care” of the Battalion training staff whose job it was to make the new soldiers ready for war and the rigours of battle, within a matter of weeks – no easy task! Brocton was notorious for troops being AWOL due to its proximity to the local town of Brocton (from which the camp took its name) Rflm. Denham greatest and only misdemeanour occurred at Brocton when he received an Admonishment (a verbal smack on the knuckles) and forfeited one day’s pay for being 2.5 hours AWOL (late returning to the Depot) in the middle of the day. Clearly a career criminal if ever I’ve heard of one!

The 35th Reinforcements were not wholly Rifle Brigade personnel but included reinforcements for other elements of the NZ Division serving in England and in France. Artillerymen, Signalmen, Engineers, Administrators, Medics and Nurses and so forth, all required regular top-ups for their own diminishing numbers. Reinforcements were sent first to their various Corps specific training schools that had been established at bases around southern England. This in itself was a vast organisation for a country contributing the numbers of soldiers NZ did, and was duplicated (or combined in some cases) for each of the major contributing allied nations such as Australia, South Africa and Canada.

Etaples Base Depot, France

Rflm. Denham spent the best part of 10 weeks at Brocton training for his role with the Rifle Brigade before the reinforcements embarked for France on 11 October 1918 (exactly one month from Armistice). Two days later they disembarked and again marched to their temporary home at the Etaples Base Depot on the French coast opposite Dover. Etaples was a pre-war training base for the British Army and could accommodate comfortably up to 35,000 troops, vehicles and equipment.

Etaples was the camp through which every soldier either arriving in France or departing would pass. It was also a major medical facility with General and Stationary Hospitals of the UK, NZ, Australia and Canada occupying the same space as up to 100,000 allied troops when the Depot was filled to capacity, as it was in 1917. The New Zealand Expeditionary Force had an area set aside in the south east of the Depot where it accommodated the NZ reinforcements and those withdrawn from the line, or being repatriated.

Into the field …

With training and a basic set of equipment consisting of a rifle, tin helmet, gas mask, change of clothing, underwear, a coat, pack and ground sheet cum rain cape, the men of the 35th were soon ready to replace soldiers from a variety of NZ units including infantry, artillery, engineers, signalmen, cooks, drivers, medics and so on. They would be replacing not only soldiers who had been killed or wounded but also those who had suffered from serious accident, from disease, illness, or been evacuated for a variety of reasons, not least being “shell shock” – and strange as it may seem, from promotion. Many soldiers indirectly ‘benefited’ from the loss of a comrade of their unit to the circumstances above. Sudden advancement in rank could come at a moment’s notice to fill a vacancy in order that the unit establishment was maintained. Not all promotions were met with joyous acceptance as they might have been in peacetime. Promotion to Lance Corporal or Second Lieutenant/Lieutenant meant a commensurate increase not only in pay, but also responsibility and risk! The ability to inspire and lead men by personal example with the requisite aggression (i.e. from the front) were paramount requisites for a leader to be successful on the battlefield. Many, particularly those swiftly promoted to Junior NCO rank, chose to relinquish their rank on request once they had experienced the responsibilities of the rank of another that they had ‘inherited’. Some proved incapable, others just did not want the responsibility finding that they had enough to cope with by just keeping themselves alive and moving forward without having the added burden of responsible for the lives of men under their command, otherwise their mates in the trenches. The value of a trusted and capable Corporal or Sergeant in the ranks of the infantry could never be overestimated.

Rflm. Denham had no such difficulties to cope with. He did what he was told, when he was told and basically kept his nose clean. The ‘green’ off the shelf soldiers who arrived with knees knocking so loudly they could have been used as alarms of an imminent gas attack, were quickly gripped up by the experienced older heads in the unit. These battle hardened soldiers would generally watch over the young (and not so young) reinforcements, guiding and coaching them when necessary, through their first experiences on the battlefield.

When Rflm. Denham arrived at his unit in the field on 22 December 1918, the 3rd Battalion was very much still engaged in mopping up operations and counting the cost for its part in the last offensive action by the New Zealand Division, the successful assault to drive the German enemy from the town of Le Quesnoy. This the NZ Division achieved without a single citizen’s life being lost – not so for the Wellingtons.

Whilst the Armistice had been signed on the 11th of November, there was still much to be done in the way routing out pockets of resistant enemy fighters, processing POWs, providing security, supply and preparation for the withdrawal of units from the field, and their repatriation. The priority for withdrawal from the field were soldiers who were wounded or sick, followed by those who had been in the field longest, and then the remainder on a draw-down basis – last in, last out. Needless to say the new reinforcement personnel would spend a considerable time in the field dealing with the aftermath of the cessation of hostilities and the preparation for withdrawal than all others.

Rflm. Denham’s stay in the field was brief. He had been in the field barely three weeks when he was taken ill with severe bronchitis. Attended to first by 3 NZ Field Ambulance, he was then taken first to 36 (British) Casualty Clearing Station at Heilly for treatment. As his condition deteriorated he was evacuated to 14 (British) General Hospital at the Etaples Base Depot pending return to England. Once in England, Rflm. Denham was admitted to the Endell Street Military Hospital at Covent Garden in Central London for the next two months. The Endell Street hospital was a Royal Army Medical Corps run hospital, and the only hospital entirely staffed by suffragists (women who supported the introduction of votes for women). By early April, Albert’s health and lung capacity had improved to the point he was deemed well enough to be moved to the NZ Convalescent Depot at Hornchurch, Essex where he remained until his ship transport back to NZ became available.

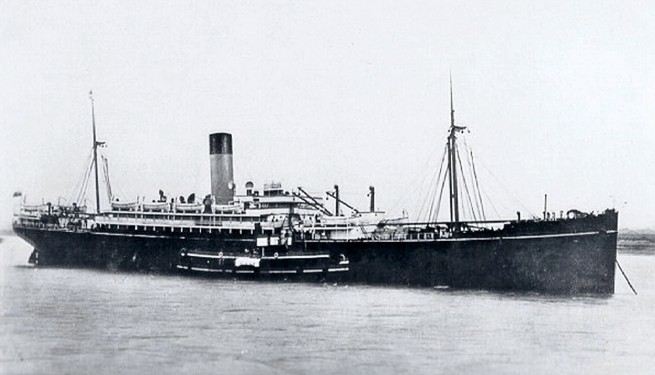

Rflm. Denham embarked on HMNZT Raranga troop transport ship at Portsmouth on 29 April for the return voyage to NZ, arriving at Wellington on 27 May 1919. Rflm. Albert Edward Denham was discharged from the NZEF on 30 May 1919.

Awards: British War Medal 1914-18 and Victory Medal

Service Overseas: 1 year, 59 days

Total NZEF Service: 1 year, 223 days

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

After the War

Albert was discharged in Wellington and returned home at 33 Dee Street in Island Bay. He quickly picked up where he left off being offered a position at his previous place of work, the Wellington Travellers Club but not as a Billiard Marker. With the benefit of the respected title and reputation of a ‘returned war veteran’ and medals to prove it, Albert was offered a position as one of the Club Stewards, a job akin to a butler, waiter, barman, duty office attendant and concierge all rolled into one. The Stewards ran the Club for all intents and purposes and Albert was, together with several other Stewards, a ‘front of house’ man, a job he very much enjoyed (and was good at it).

Albert remained at the Club in Wellington and married a Wellington girl in 1922, Charlotte Edith May Ann SMALL (1899–1988). Together, they lived with Albert’s youngest sister Emma, a lift operator, at 9 Sidey Street in the Central City until Emma eventually moved into her own place at Miramar. The Denham’s had two children – Jean Margaret and a son, George Albert Denham.

Albert’s mother Charlotte died in 1932, and his father George Snr. ten years later in 1942. Albert, Charlotte Edith and their son George Jnr. moved in with Albert’s widowed father at 33 Dee Street atop the hills at Island Bay. Albert and Charlotte remained at Dee Street for almost 20 years before deciding to make the move out of Wellington after Albert had retired from his position at the Traveller’s Club in 1953. Their then recently married son George Albert had moved from Hastings to Tauranga and so Albert and Charlotte Edith bought a house in the new Tauranga suburb of Otumoetai.

George had been a music shop assistant in Hastings and had been teaching music when he married Mavis Jean HALL (1932-2013) however after the birth of their two children, Keith Albert Denham (b 1946) and Faye Elaine Denham (1952-2006), the marriage failed and divorce followed. George re-married in 1966 to Valerie Mabel GORE and from this marriage, a son Gregory and daughter Karen resulted. The family moved from Hastings to Tauranga where George had continued to teach music whilst he started a photographic business. Valerie specialised in photographing weddings, birthdays and event photography.

By 1978 George and Valerie had retired and were living at No 54 The Esplanade at Omokoroa Beach in the Western Bay of Plenty. Unfortunately for the Denham’s the transformation of Omokoroa by housing developers in the 1980s and 1990s to accommodate a burgeoning population of those seeking an alternative to the traditional areas for the wealthy to retire to, such as Mount Maunganui and Papamoa Beach, shattered the solitude and changed the face of Omokoroa forever – and not necessarily for the good! Never again would it be the oasis of rural tranquillity it had once been, that I recalled it to be in the 1960s.

Meanwhile Albert and Charlotte had been ticking along in town at 13 Stratford Street, Otumoetai and had created a very comfortable life for themselves. Albert had done some property developing of his own and was the owner of some valuable property in downtown Tauranga which kept him busy until retirement. In 1986 Charlotte had gone into a nursing home for the last two years of her life and Albert would drive to visit her every day until her death on the 1st January 1988, aged 88. A devoted couple, Albert saw out his remaining days at Stratford Place but was frankly lost without his Charlotte. On 18 September 1989, Albert Edward Denham (92) passed away in Tauranga Hospital. Albert and Charlotte are buried together in the Pyes Pa Cemetery, Tauranga.

Australia bound

In 1988 George Denham, Valerie and son Greg had gone to Queensland to visit the Brisbane Expo and while their had stayed with George’s son Keith. Things obviously did not go well as Valerie started divorce proceedings against George when they returned; they separated in 1989, later divorcing. Valerie moved to Tauranga and remarried.

George had the job of finalising his father Albert’s estate and the clearance of the house in Stratford Place prior to its sale. It is believed that George may have found his father’s war medals at this time. What is not known however is why the medals appeared to have been placed in the position they had been found by the R’s. Their placement in the garage at Omokoroa suggested the medals had been hidden rather than dropped or accidentally misplaced?

Once he had completed administering his father’s estate, George returned to Queensland permanently in 1990 to live with son Keith and Linda while renting out his house in the interim. George finally sold No 54 at Omokoroa around 1994 as he wanted to finance a unit on the Gold Coast, and had also wanted to travel. The house was therefore, in another owner(s) and/or tenant hands from 1994 to 2007 when the R’s purchased the property. Remarkably Albert Denham’s medals had remained undiscovered in the garage all that time!

George Denham was also not done with marriage. Whilst holidaying abroad in Russia he met English divorcee, Irene BEVAN, the mother of three adult children. George and Irene were subsequently married and lived at Kirra on the Gold Coast before each went into an aged care home at Tweed Heads in South Queensland, in 2016 and 2017 respectively. George Denham died in June 2017 at the age of 94, and wife Irene in August 2019, aged 88 years.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Researching Albert Denham

Enter Haydon Jones and his “Good Sorts” program – Jan contacted me saying she had been doing some research to try and find the Denham family to return the medals but had come to the conclusion Albert may have gone to Australia. Jan had not managed to make any further progress since relocating from Omokoroa to the Coromandel – could I help to with research to reunite Albert’s medals with his family?

My search for Denham descendants had started with Albert’s cenotaph file which unsurprisingly it was devoid of much useful detail information as he had arrived in England just prior to Armistice Day in 1918. It was not until I made a connection with the Denham descendants from the Bay of Plenty, now living in Australia, that more of Albert’s life story came to light.

Having put the Denham case on hold for some months while other cases were being wound up, I received an inquiry from Jan as to how I was going with her case. Jan said that since their move she had had the opportunity to make a visit to Albert Denham’s grave in Tauranga to see if his headstone provided any clues regarding other family members, such as the names of their children or grandchildren. The net result was that Jan had found George Denham’s son from his second marriage to Valerie – Gregory, or Greg as he is known, a married man with a family of his own. Great progress by Jan. As she had told Greg about the medals, she asked me if I would send them back to her so that she could pass them on – which I did.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

New information

They say it never rains – it pours! Barely 48 hours after speaking with Jan, out of the coincidental blue came an email response from one of the Ancestry Tree authors who had the Denham family within their ‘branches’. I had sent a number of questions re Denham descendants to all those who had featured this Denham family on their family trees. My requests had been out in the ether for more than twelve months or more! As it happened the response had not come from any one of these authors, but rather from a direct descendant of Albert Denham, his grandson Keith Albert Denham. Keith had been sent my questions by one of the Ancestry Tree authors who happened to know Keith and his partner Linda. How spooky is that?

The email I received (on behalf of Keith) was authored by Linda (the family genealogist) who outlined the Denham family structure as she and Keith knew it. It seems George had effectively estranged his children from each other , and himself as the result of his marriages. Apart from one occasion George and Valerie had stayed with Keith and his family when visiting Queensland, once he had emigrated George only associated with Keith and Linda after he had become ill towards the end of his life. Keith and Linda had nursed George until his death. It mattered not, as Keith and Linda had managed to construct the known parts of their family tree sufficient for me to add the remaining picture I had uncovered.

I was still amazed at the coincidence of Keith and Linda’s contact, just days after Jan’s email! However, this contact had created a problem – I needed to advise Jan of my findings as it could have a direct impact upon who the most entitled Denham descendant would be to receive Albert’s medals? Having already returned the medals to Jan, I needed to prove (quickly) that Keith Denham was Albert’s nearest living direct descendant and therefore entitled to the medals ahead of any other known claimant. There were also extenuating circumstances I had been made aware of that I thought Jan should also know since she remained the legal owner of the medals and ultimately the person to decide to whom the medals would go.

Pros and Cons

Continued dialogue between Keith, Linda and myself was both revealing and compelling as regards Keith’s claim. Keith had been very close to his grandparents and Albert in particular, when his grandparents had moved from Wellington to Otumoetai about 1961. Albert’s concern for his grandson and the growing indifference toward him by his father George, caused by an unsettled upbringing resulting from George’s relationships and failed marriages. He had tended to estrange his own children and at some point also fell out with his father over a business situation, among other things. The business situation concerned a residential block of flats that Albert owned in Tauranga’s CBD and was at the heart of George’s discontent, the fallout having far reaching consequences for Keith in particular.

Prior to the dispute with son George, Albert had verbally promised his grandson Keith that when he died, Keith was to have his gold pocket watch. As far as Albert’s medals were concerned, his wishes were not known.

By the time Albert died in 1989 grandson Keith had was living in Queensland. When George and Valerie returned to Tauranga after the 1988 Expo in Brisbane, they separated. George was also landed with the responsible of tidying up his father’s estate after Albert died the following year. Apparently still piqued by his father’s decision over the property in the CBD (which clearly did not include George as a beneficiary), George seems to have either absentmindedly or knowingly, given little thought to the disposal of his father’s personal valuables. The proposed gift of Albert’s pocket watch destined for grandson Keith never happened. The pocket watch together with Albert’s other personal keepsakes were George shared between his children by his second wife Valerie – presumably this had included Albert’s medals? A heartbroken Keith was excluded from any memento of his beloved grandfather.

What happened to Albert’s medals?

The unresolved question at this stage was: What circumstances could have caused Albert Denham’s war medals to be in the garage at 54 The Esplanade undetected for at least 13 years after the house had been sold by George? There are a number of possibilities but none conclusive.

Assuming that after his death Albert Denham’s medals were in son George’s possession, the medals may have been lost or misplaced somewhere in or around the house at any time. This seems unlikely given their apparent hiding place in the garage. The possibility of children playing with Albert’s medals and hiding them, or being misplaced as the house contents was emptied prior to its sale in 1994, are also possibilities. One would like to think the medals were not deliberately left behind by George, still piqued at his father over the block of flats affair?

The fortunate part of these most unfortunate family circumstances was the R’s discovery of the medals when they bought the house. This together with their continued safeguard by Jan and her desire to someday get the returned to the Denham family.

Decision …

From emails between myself, Keith and Linda I was able to establish the location of number of other Denham families that were descended from Albert’s siblings – those of his sister Louisa CLEAVER, and brother Herbert Denham. From these I had put together a short list of probable and possible relatives who I attempted to contact without success.

Linda and Keith’s email had negated any further need for me to pursue these as Keith had proved to be the closes direct descendant at that time. Greg Denham (and his sister) were a generation younger than Keith’s so for me the answer was obvious as to whom I would have sent the medals to.

I advised Jan of my findings and gave her the back story given me by Keith and Linda. I made a recommendation however it was Jan’s prerogative to make the final decision as to whom the medals went to since she was still the legal owner. Not an enviable decision to make but in some ways an easy one to make when the circumstances of Albert’s original wishes were taken into account, as well as the generational seniority between Keith and Greg, and their relative lines of descent.

Jan contacted me a few weeks later and agreed with my recommendation. She had spoken with the Denhams in Australia and with Greg. Satisfied that Keith was the most appropriate person to receive the medals, Jan had sent them to Keith.

Keith now has his grandfather’s medals and is over the moon! As he said, he had not one memento of his beloved grandfather and had always lamented the loss of his grandfather’s pocket watch, at the hands of his father George. Now he has something he can be proud of and wear to represent his late grandfather on appropriate occasions.

Future guardianship

Keith also has a succession plan worked out for the medals. Next in line will be Keith’s only son Matthew Francis Albert Denham, who will be followed by Matthew’s son and Keith’s grandson, Cooper Jai Albert Denham. A worthy plan for a treasured family heirloom once more back in the hands of the family to whom they rightfully belong.

Keith Albert Denham, now 72 and retired, never thought he would ever own anything which had belonged to his grandfather Albert. He is very grateful to Jan for her care of the medals and her decision to give them to him. Keith is looking forward to next Anzac Day when he can proudly honour the memory and service of his grandfather, Albert Edward Denham, by wearing his medals.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Special thanks to Jan for her contributory research, care and safekeeping of Albert Denham’s medals, and to Linda and Keith for helping to connect the threads of this case.

The reunited medal tally is now 289.